Abstract

Collateral spread of apoptosis to nearby cells is referred to as the bystander effect, a process that is integral to tissue homeostasis and a challenge to anticancer therapies. In many systems, apoptosis relies on permeabilization of the mitochondrial outer membrane to factors such as cytochrome c and Smac/DIABLO. This permeabilization occurs via formation of a mitochondrial apoptosis-induced channel (MAC) and was mimicked here by single-cell microinjection of cytochrome c into Xenopus laevis embryos. Waves of apoptosis were observed in vivo from the injected to the neighboring cells. This finding indicates that a death signal generated downstream of cytochrome c release diffused to neighboring cells and ultimately killed the animals. The role of MAC in bystander effects was then assessed in mouse embryonic fibroblasts that did or did not express its main components, Bax and/or Bak. Exogenous expression of green fluorescent protein-Bax triggered permeabilization of the outer membrane and apoptosis in these cells. Time-lapse videos showed that neighboring cells also underwent apoptosis, but expression of Bax and/or Bak was essential to this effect, because no bystanders were observed in cells lacking both of these MAC components. These results may guide development of novel therapeutic strategies to selectively eliminate tumors or minimize the size of tissue injury in degenerative or traumatic cell death.

Apoptosis is essential to tissue homeostasis and the development of multicellular eukaryotic organisms. There are two main pathways leading to programmed cell death, which converge at activation of executioner caspases (eg, caspase 3).1 Extrinsic apoptosis is initiated by external signals, when conditions in the extracellular environment, such as the release and recognition of Fas ligand, induce the cell to commit suicide. This pathway often utilizes turning on of the initiator caspase 8, which directly activates caspase 3. Intrinsic apoptosis is a mitochondria-dependent pathway triggered in response to both internal cellular damage and extracellular cues, in part through crosstalk with the extrinsic pathway. Various forms of cellular stress, such as the detection of damaged DNA or growth factor withdrawal, can activate the intrinsic pathway. The ensuing outer membrane permeabilization and release of cytochrome c into the cytosol are considered the commitment step of intrinsic apoptosis. Released cytochrome c binds Apaf-1 to form apoptosomes, which then cleave initiator pro-caspase 9, which in turn triggers activation of caspase 3. Thus, both the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptotic pathways converge at the activation of executioner caspases.

The Bcl-2 family of proteins monitor cellular status and work synergistically to regulate entrance into apoptosis. Mutations affecting the members of the Bcl-2 family cause cancer and several degenerative diseases.2 In normal cells, a functional excess of antiapoptotic proteins (eg, Bcl-2), relative to proapoptotic proteins (eg, Bax and Bak), suppresses cell death. However, abnormalities such as DNA damage are sensed by p53, and activation of this transcription factor results in an up-regulation of Bax expression; Bax is subsequently activated and translocated to the mitochondria. On the other hand, Bak is constitutively expressed in the mitochondrial outer membrane, but (like Bax) it is inert until activation. Increased expression and activation of Bax and/or Bak induces cell death through the intrinsic apoptotic pathway.

Specifically, Bax and/or Bak form the mitochondrial apoptosis-induced channel (MAC) in the outer membrane. MAC makes the mitochondrial outer membrane permeable to proteins normally constrained within the intermembrane space, such as cytochrome c and Smac/DIABLO. Once in the cytoplasm, these proteins trigger a chain of events that leads to the destruction of the cell. MAC formation and permeabilization of the outer membrane have been consistently reported in a variety of cell lines during different apoptotic insults, such as interleukin-3 deprivation, green fluorescent protein (GFP)-Bax expression, and kinase inhibition.3,4 Once a sufficient-sized MAC is formed, proapoptotic factors such as cytochrome c are released from the intermembrane space into the cytosol.5 This mitochondrial permeabilization event through MAC formation corresponds to the commitment step of apoptotic death.6,7

The bystander effect is an extension of the apoptotic cascade, whereby cell death is induced in cells nearby dying cells.8–13 The mechanisms underlying bystander effects are not well understood, and little is known of the role of Bcl-2 family proteins in this phenomenon. Reports have indicated that apoptosis is suppressed in cells overexpressing Bcl-2, but the efficacy of protection is diminished when gap junction intercellular communication exists with neighbors that do not overexpress Bcl-2.14,15 Apoptosis, which was robust 3 days after detachment of retinas, was suppressed in mouse knockouts for proapoptotic Bax16; however, gap junction intercellular communication was not evaluated in that study. These findings nevertheless suggest that Bcl-2 family proteins either directly or indirectly regulate bystander effects. Finally, our research group has recently shown that a bystander effect reliant on gap junction intercellular communication was induced when MAC function was mimicked by microinjection of cytochrome c.17

Here we present the novel finding that inducing mitochondrial apoptosis by microinjection of cytochrome c caused an in vivo bystander effect in Xenopus laevis embryos. Furthermore, a bystander effect occurred in cultured mammalian cells on exogenous expression of GFP-Bax. Release of Smac-cherry from mitochondria indicates GFP-Bax induced MAC function (ie, permeabilization of the outer membrane and release of death factors into the cytosol). Knocking out of either Bax or Bak delayed the bystander effect, but did not prevent it. Importantly, no bystander effect was observed in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) lacking both Bax and Bak, indicating that MAC formation is a necessary step in this specific bystander pathway. These findings suggest that intrinsic apoptosis can cause a bystander effect in vivo and that Bax and/or Bak expression is requisite to inducing bystander death in cells nearby dying cells in vitro. We hypothesize that intrinsic apoptosis generates an as yet unidentified death signal that results in a bystander effect. These observations may provide insight into selective cell death in tumors and so may guide development of novel therapeutic strategies to selectively eliminate tumors or minimize the size of tissue injury in degenerative or traumatic cell death.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Bak+/+Bax+/+, Bak−/−Bax+/+, Bak+/+Bax−/−, and Bak−/−Bax−/− MEFs were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% nonessential amino acids, 1% L-glutamine, 1% penicillin, 1% streptomycin, and 20 mmol/L HEPES as previously described.4 Cells were grown at 37°C in incubators supplied with 5% CO2.

Microscopy of Cultured Cells

Time-lapse images of cultured cells were captured using a SPOT RT (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI), Nikon DS-2MBW (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), or CoolSNAP HQ2 monochrome camera (Roper Scientific-Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) on a Nikon Eclipse TE 300 or Nikon Eclipse TE2000-E microscope equipped with differential interference contrast (DIC) optics, a 20× plan APO objective (numeric aperture 0.17), and shutters. The images were analyzed offline for the occurrence of apoptosis in transfected (target) cells and neighboring (bystander) cells from the DIC and fluorescence images using SPOT imaging software v. 5.4 or NIS-elements AR 3.0. Cells were scored apoptotic on the basis of morphological changes such as retraction, rounding up, blebbing, and nuclear condensation, as previously described.18

Maintenance and Manipulation of Xenopus Embryos

Eggs from X. laevis were fertilized in vitro, dejellied in 2% cysteine in 0.5 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.8, 10 mmol/L NaCl, 0.2 mmol/L KCl, 0.1 mmol/L MgSO4, 0.2 mmol/L CaCl2, and 0.01 mmol/L EDTA. Amphibian embryos are maintained at room temperature, approximately 22°C.19,20 Embryos were staged according to Nieuwkoop and Faber.21 Embryos were microinjected at the four-cell stage with 8 ng cytochrome c or an equivalent volume of water. Embryos were visualized with an Olympus SZX12 stereo microscope and photographed with a DP10 digital camera (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Time-lapse video microscopy sequences were generated using an Olympus ColorView 12 camera system. Caspase activation was monitored via cleavage of recombinant poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) on Western blots, as previously described.22 Detection of an 85-kDa cleavage fragment of PARP indicates activation of caspase 3.

Transfections

The GFP control and GFP-Bax plasmids were kindly provided by Richard Youle (National Institutes of Health). The plasmid encoding Smac-cherry, which is the import sequence from the intermembrane space protein Smac fused to mCherry, was a gift from David W. Andrews (McMaster University). Plasmids were prepared using commercially available midi-prep kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The MEFs were transfected (10%–30%) using a mixture of Lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or polyethyleneimine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis) and plasmids encoding the fusion protein GFP-Bax, Smac-cherry, or control plasmids encoding GFP alone.17 Cells were then incubated for approximately 5–18 hours at 37°C before time-lapse video microscopy was initiated. Cells expressing the gene of interest were identified by their green or red fluorescence. Rose chambers were then assembled, and cells were monitored using DIC and fluorescence time-lapse video microscopy.17 Cells were scored dead if they were rounded up, were blebbing, and had stopped dividing. The percentage of bystander dead cells was determined 24 and 48 hours after transfection by the following formula: % bystander dead cells = (a − b)/(c − b), where a is the number of dead cells, b is the number of transfected green cells, and c is the total number of cells. Note that dead cells sometimes float out of the field, which can lead to an underestimation of the magnitude of the bystander effect. Hence, we routinely relied on the statistical difference (P-value) between GFP and GFP-Bax expressing cells that were handled in parallel when determining the presence or absence of a bystander effect. Routinely, cells were also stained with Hoechst 33342 to assess nuclear condensation.

Results

A bystander effect was observed after mimicking MAC function by cytochrome c microinjection in target cells in vivo in X. laevis embryos. A bystander effect was also induced by exogenous expression of proapoptotic Bax in cultured cells. However, this effect required expression of either Bax or Bak, because double-knockout cells failed to produce bystanders. These findings indicate that mitochondrial apoptosis generates a death signal that propagates and kills nearby cells through MAC-dependent apoptosis, as confirmed by its requirement of Bax or Bak.

Microinjection of Cytochrome c Induces a Bystander Effect in Xenopus Embryos

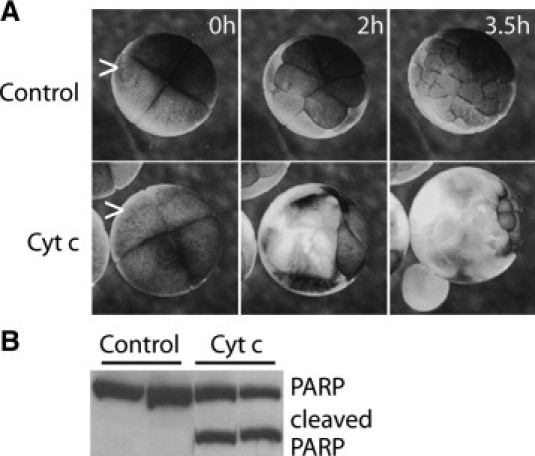

Microinjection of cytochrome c in vitro imitates MAC function and leads to mitochondrial apoptosis in many cell types.18,23–25 Activation of caspases, changes in pigmentation, and a progressive loss of resting membrane potential of the plasma membrane have been reported after this treatment in Xenopus oocytes.9,10 Cusato et al9 also observed a bystander effect in electrically coupled oocytes after microinjection. Microinjecting cytochrome c into single cells of 4-cell-stage Xenopus embryos causes an in vivo bystander effect, compared with injection of water (Figure 1; see corresponding Supplemental Video S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). After 3.5 hours, cytochrome c microinjected embryos had 75% fewer cells than control (water) microinjected embryos (9 ± 2 and 36 ± 6, respectively). A bystander effect was also observed when a single cell was microinjected in later stages, up to the 16-cell stage (data not shown). Bystander death involved apoptosis, as indicated by onset of markers such as membrane blebbing and loss of pigmentation. Caspase activation was evidenced by cleavage of exogenous PARP (Figure 1B). These findings show that mimicking MAC formation and early intrinsic apoptosis triggers generation of death signals that induce apoptosis in neighboring cells in vivo.

Figure 1.

Bystander effects are induced in vivo by mimicking mitochondrial apoptosis-induced channel (MAC) formation. Single cells (carets) in four-cell Xenopus laevis embryos were microinjected with 8 ng cytochrome c (Cyt. C) or water (Control). A: Selected frames are shown from a time-lapse video of embryos at the indicated times postinjection (See Supplemental Video S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). While the control embryos continued to divide, a wave of cell death (cells lose pigmentation) encompassed much of the cytochrome c-injected embryos by 3.5 hours. Loss of pigmentation was estimated at 84 ± 9% of the cells in embryos in the video by 3.5 hours, using SPOT Imaging software. B: Western blot shows that executioner caspase 3 was activated, as indicated by cleavage of recombinant poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) in lysates of embryos microinjected with cytochrome c (Cyt. C), but not water (Control). Duplicate samples are shown.

Exogenous Expression of Bax Triggers Apoptosis Regardless of Endogenous Bax and Bak Expression Status in Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts

Cytochrome c microinjection mimics the early steps of intrinsic apoptosis and triggers a bystander effect in vivo (Figure 1) and in vitro.18,23–25 These experiments did not determine whether the death signals generated by apoptotic cells induce intrinsic apoptosis in nearby cells, rather than some other pathway such as necrosis or extrinsic apoptosis. This determination is important, because it may influence therapeutic strategies. To examine the specific role of MAC formation in the bystander cell death, further experiments were conducted with cells that do and do not express proapoptotic Bax and Bak. These two multidomain Bcl-2 family proteins are integral to intrinsic apoptosis. They form, at least in part, the structure of MAC3,4,26 and hence are required for release of cytochrome c from mitochondria.27–29

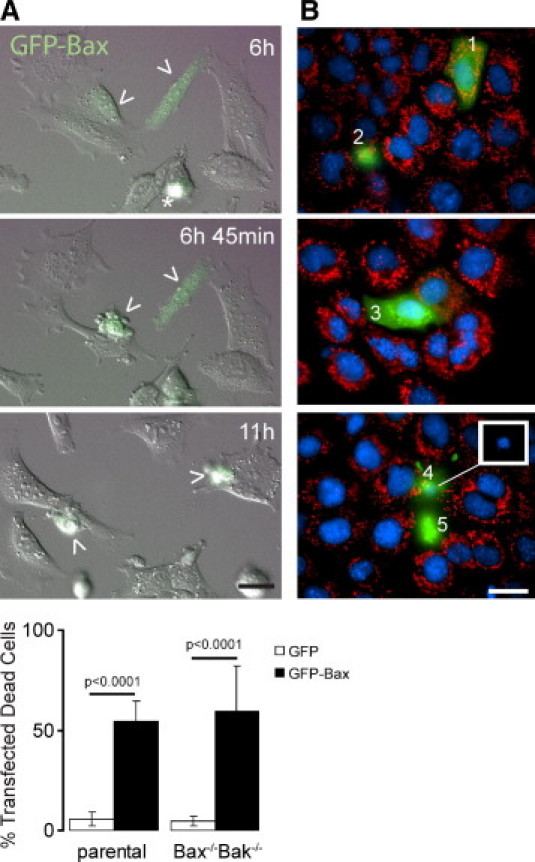

To determine the ability of GFP-Bax to induce apoptosis, a fraction (10%–30%) of MEFs on a coverslip were transfected with plasmids encoding GFP-Bax or GFP. These cells were monitored for the onset of apoptosis with dual fluorescence/DIC time-lapse video microscopy (Figure 2). Apoptosis, as indicated by morphological signs such as rounding up, began approximately 6 hours after fluorescence was detectable in cells expressing GFP-Bax. In contrast, cells transfected with plasmids encoding GFP showed little sign of apoptosis. That is, while few Bax+/+Bak+/+ cells (parental, 5.7 ± 3.6%) and Bax−/−Bak−/− cells (double knockouts, 4.6 ± 2.2%) died 24 hours after transfection with plasmids encoding GFP, most transfected cells died if the plasmids encoded GFP-Bax (Bax+/+Bak+/+, 54 ± 10.3%; Bax−/−Bak−/−, 59.5 ± 22%). Cells were scored dead if they rounded up, shrank, blebbed, and had condensed nuclei. Although the cells were not precisely synchronized, the onset of apoptotic markers was, in general, as follows. Diffuse green fluorescence (Figure 2B, cell 1) became punctate (cell 3), putatively reflecting MAC formation. In accord with a previous report,30 mitochondria depolarized sometime after MAC assembly, as indicated by a lack of staining by MitoTracker CMXROS Red dye (cell 3). Subsequently, cells were rounded up and their nuclei were condensed (cells 2, 4, and 5). These results establish that exogenous expression of GFP-Bax, but not GFP, induced intrinsic apoptosis, regardless of whether the cells endogenously expressed Bax and/or Bak.

Figure 2.

GFP-Bax induces apoptosis in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). A: Differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescence merged images selected from a time-lapse video at indicated times after transfection of parental MEFs with plasmids encoding GFP-Bax (arrowheads). Note that the rounded cell (asterisk) at 6 hours is in mitosis. Bottom: A histogram shows the percentage of parental and Bax−/−Bak−/− cells that died 24 hours after transfection with plasmids encoding either GFP or GFP-Bax. Data are shown for 2000–5000 cells/condition. Error bars indicate SEM. B: Fluorescent images show different stages of apoptosis in parental MEFs expressing GFP-Bax (1–5, green) at 22–24 hours after transfection. Mitochondrial membrane potential and nuclear morphology were assessed by the accumulation of MitoTracker Red CMXROS (red) in mitochondria and Hoechst 33342 (blue), respectively. Cell 1 shows cytosolic GFP-Bax with normal mitochondrial membrane potential and nuclear morphology. Cell 3 has a normal nuclear morphology and shows some GFP-Bax relocation as stippled (green) but depolarized (not red) mitochondria. Cells 2, 4, and 5 are in advanced apoptosis after Bax relocation, mitochondrial depolarization, nuclear condensation, and rounding up. Inset: To improve resolution in merged images, the white box shows nuclear condensation of cell 4 recorded on the blue channel. Scale bars = 20 μm.

Bax and/or Bak Are Essential for Bystander Cell Death

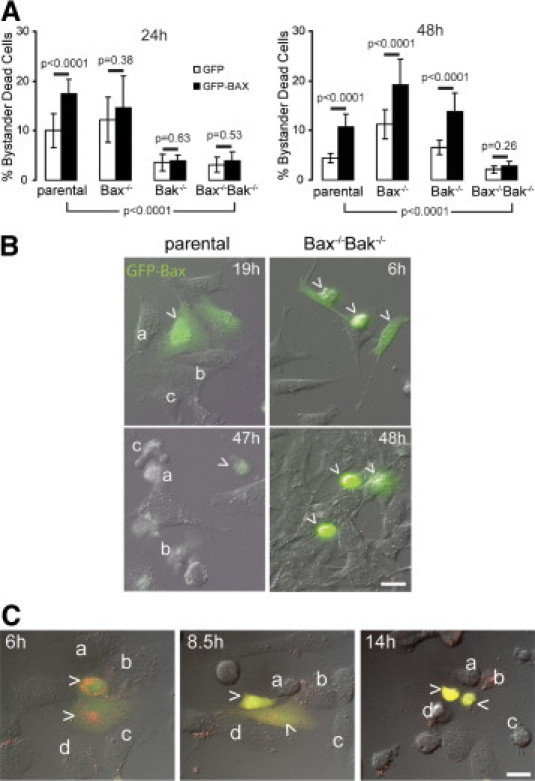

Cells lacking both endogenous Bax and Bak die when transfected with plasmids encoding GFP-Bax (Figure 2). Importantly, MAC activity and function (permeabilization of the outer membrane) require Bax or Bak expression.5 Thus, we wanted to determine first whether GFP-Bax kills cells through MAC function. This question was addressed using parental MEF cells transfected with GFP-Bax and Smac-cherry, a plasmid encoding a fragment of the intermembrane space protein Smac fused to the C-terminus of red fluorescent mCherry. DIC and fluorescence microscopy were used to monitor cell death and Smac-cherry release from mitochondria, a marker of MAC function in permeabilization of the outer membrane (Figure 3C). At ∼8.5 hours, Smac-cherry leaked into the cytoplasm and the cells turned yellow (Figure 3C, caret) and subsequently died (not shown). At ∼14 hours some nontransfected cells died as bystanders (Figure 3C, cells a–c). These results indicate GFP-Bax expression induced target cell deaths through MAC function.

Figure 3.

Mitochondrial apoptosis induced a Bax/Bak-dependent bystander effect. The fraction of dead cells (excluding transfected green cells) in several fields was determined 24 and 48 hours after ∼10% of the cells were transfected in parallel with plasmids encoding either GFP or GFP-Bax. Once green fluorescence was detected, cells expressing GFP-Bax usually died within 6 hours. A: Histograms show the fraction of bystander dead cells 24 or 48 hours after transfection. P-values were calculated through Fisher's exact statistical test and were considered significant if P < 0.05. For example, the percentage of bystander dead cells is significantly higher (P < 0.0001) if the cells endogenously express Bax and/or Bak (ie, Parental, Bax−/−, and Bak−/−), compared with Bax−/−Bak−/− cells at 48 hours. Data are shown for 5000–10,000 cells/condition. Error bars indicate SEM. B: DIC and fluorescence merged images selected from time-lapse videos at indicated times after transfection of parental and Bax−/−Bak−/− cells with plasmids encoding GFP-Bax as indicated. Top: Bystanders (a–c) were often noted nearby parental cells expressing GFP-Bax (arrowheads). Bottom: Bax−/−Bak−/− cells that expressed GFP-Bax (arrowheads) were green and died as target cells. No Bax−/−Bak−/− cells died, unless they were expressing a detectable level of GFP-Bax; that is, there were no bystanders after 48 hours. C: DIC and fluorescence merged images selected from a time-lapse video at indicated times after transfection of parental MEF cells with plasmids encoding GFP-Bax (green) and Smac-cherry (red) (arrowheads). At ∼8.5 hours, Smac-cherry leaked into the cytoplasm and the cells turned yellow (arrowheads) and died subsequently (not shown). At ∼14 hours some nontransfected cells died as bystanders (a–c). Scale bars = 20 μm.

Do the Bax or Bak expression levels of cells nearby those expressing GFP-Bax affect their likelihood of dying? To address this question, the bystander effect was monitored in parental, Bax and Bak single-knockout, and Bax/Bak double-knockout MEFs. The different cell lines were transfected with plasmids encoding GFP-Bax or GFP in parallel. DIC and fluorescence microscopy was again used to monitor death in the transfected and neighboring cells after 24 and 48 hours. The parental and Bax−/−Bak−/− cells expressing GFP-Bax died by apoptosis (Figures 2 and 3). A robust bystander effect was observed in parental cells at 24 and 48 hours, as indicated by the significant increase in bystander dead cells nearby those expressing GFP-Bax, compared with GFP (P < 0.0001) (Figure 3, cells a–c). In contrast, nearby Bax−/−Bak−/− cells were resistant to this death and failed to show any bystander effect at 24 or 48 hours (P = 0.26 and 0.53, respectively). These results are consistent with those of Wei et al,31 who reported that cells from mice lacking both Bax and Bak are resistant to a wide range of proapoptotic stimuli. These findings suggest that Bax and/or Bak expression are requisite for these bystander effects and implicate intrinsic apoptosis as a central pathway in this phenomenon.

Do Bax and Bak act synergistically in response to death signals to rapidly induce apoptosis in bystander cells? Examination of the ability of GFP-Bax to induce bystander effects in the single-knockout cell lines revealed just that. Unlike the parental cells, neither the Bax nor the Bak single-knockout cells showed a significant bystander effect at 24 hours induced by GFP-Bax compared with GFP (P = 0.4 and 0.6, respectively) (Figure 3A). Nevertheless, by 48 hours after transfection, both Bax and Bak single-knockout cells showed a significant bystander effect (P < 0.0001), similar to that of the parental cells. The results with the single-knockout lines at 48 hours show both Bax and Bak can each mediate bystander effects, and the delay in onset of the bystander effects suggests that these proapoptotic proteins may normally act in unison.

Although not as prevalent as cell death mediated by direct interaction with a dying cell (Figure 1), it should be noted that cell death was not limited to cells adjacent to transfected GFP-Bax cells in the parental and single-knockout cell lines. A bystander effect was also seen in cells that were in close vicinity to, but not in direct contact with, transfected cells (Figure 3B, top). For simplicity, the death of cells adjacent and nonadjacent to transfected cells are referred to as first-order and second-order bystander effects, respectively. We observed no substantial difference in the incidence of first- and second-order bystander effects in parental MEFs expressing exogenous GFP-Bax (P = 0.12; data not shown). Nonetheless, the incidence of second-order bystander effects suggests that death factors are released into the media and that this extracellular pathway contributes to the total cell death observed. That is, dying cells release killing factors into the surrounding environment that entice other cells in the vicinity to enter apoptosis. Future studies may determine whether the expression levels of Bax and Bak affect the contribution of either intracellular or extracellular pathways. Finally, cells expressing GFP-Bax, as indicated by green fluorescence, sometimes underwent cell division (data not shown). This finding raises the question of whether cell cycle checkpoints monitor Bax expression or are somehow circumvented by Bax during apoptosis.

Discussion

The Bcl-2 family of proteins are crucial regulators of intrinsic apoptosis, controlling formation of MAC, a cytochrome c release channel. In previous work, microinjection of cytochrome c and exogenous expression of tBid were used to mimic MAC function and induce a bystander effect in a human osteosarcoma cell line.17 Here, we microinjected cytochrome c into Xenopus embryos and found that MAC function induces a bystander effect in vivo. Next, by quantification of dead cells nearby cells transfected with GFP-Bax or GFP in knockout mammalian cell lines, we found that the MAC components Bax and Bak were required for bystander effects.

Microinjection of cytochrome c into single cells of Xenopus embryos activated intrinsic apoptosis and induced a wave of cell death that eventually killed the whole embryo (Figure 1; Supplemental Video S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). PARP cleavage assays revealed activation of caspases, which biochemically demonstrated the involvement of apoptosis (Figure 1). Other studies have shown that apoptosis in Xenopus embryos is regulated by Bcl-2/Bax, thus implicating MAC.32 Hence, mimicking MAC function in a single cell likely generated a death signal that subsequently killed adjacent cells. The death signal probably entered adjacent cells via intercellular communication pathways, likely gap junction intercellular communication and cytoplasmic bridges,33–35 rather than via an extracellular pathway, because water-injected embryos adjacent to those injected with cytochrome c were unaffected within the time frame of the experiment. Although this result may have developmental implications, it is exciting that bystander killing can be reproduced in vivo at this level.

These in vivo results may influence the study of the efficiency of cell death during apoptosis-inducing chemotherapies. These embryonic cells are pluripotent and hence represent a stem cell model system that may be applicable to metastases and to some tumors resistant to chemotherapy. Future experiments should also include more differentiated cells. Nevertheless, the role of both pluripotent and differentiated cells in metastasis as well as in degeneration is currently a subject of great interest.

Bax and Bak were examined for their roles in bystander effects. These proapoptotic proteins may be functionally redundant in the bystander effect and hence are therapeutic targets for chemotherapies and for treatments for degenerative maladies such as Parkinson's disease. The processes of activating Bax and Bak may be quite different, for one is normally cytosolic and the other is an integral protein of the mitochondrial outer membrane. To assess the requirement of MAC components Bax and Bak in a bystander effect, MAC function was induced in MEFs by exogenous expression of GFP-Bax, and an evaluation of nearby cell death was undertaken. Single knockouts for Bax and Bak had significantly delayed bystander effects, compared with parental cells, but eventually mounted an effect comparable to parental cells. In striking contrast, Bax−/−Bak−/− cells did not reveal any bystander effects 2 days after transfection. Thus, elimination of one of these proapoptotic proteins delayed onset of bystander effects, but knocking out both Bax and Bak completely abolished this phenomenon. This finding suggests that Bax and/or Bak may have additional regulatory functions in diffusion of a death signal to other cells.

Bystander death was observed in adjacent cells and in cells not directly connected to dying cells. This death was specific, because it was observed neither in Bax−/−Bak−/− cells expressing GFP-Bax nor in any of the cell lines after transfection with control GFP. Thus, exogenous GFP-Bax expression may mediate bystander effects through both intracellular and extracellular pathways. Although we did not assess each pathway individually here, our previous studies showed that gap junctions are required for the bystander effect induced by microinjection of cytochrome c in osteoblastic cells.17 By contrast, the effect of a putative extracellular death signal was possibly underestimated in our experimental conditions, where cells were grown in a large volume of extracellular media (0.5 ml). Our other studies suggest that an extracellular death signal is secreted by breast cancer cells expressing death domain 1, a truncated form of a transcription factor.36 However, the death signal and the environmental factors that control both intracellular and extracellular pathways have yet to be definitively identified.

In summary, apoptosis is a highly regulated process of cell turnover and plays fundamental roles in tissue homeostasis, development, and other important physiological processes. Dysregulation of apoptosis, however, can contribute to the pathogenesis of several human diseases, including cancer, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease. Given that the induction of bystander cell death has potentially important implications for development of novel therapeutic strategies, a necessary first step is to better understand the mechanism or mechanisms involved in induction of the bystander effect. For instance, MAC is a therapeutic target, based on the premise that opening this channel will commit a cell to die and that blocking MAC may prevent cell death.6,7,37–39 Although death resistance in some cancers has been associated with down-regulation of gap junction function, another study has shown that diffusion of a cell death factor does not seem to occur in a gap junction-coupled rat bladder carcinoma cell line.40 This effect may be due to inhibition of MAC formation by Bcl-2 overexpression. Thus, the bystander effect may be regulated not only at the level of the diffusion pathways, but also at the point where a death signal is generated and released. These observations are enticing and may have important implications for health, irrespective of these gaps in knowledge.

Acknowledgments

We thank Richard Youle (National Institutes of Health) for providing the GFP and GFP-Bax plasmids, David W. Andrews (McMaster University) for providing Smac-cherry plasmid, and Douglas Morse (NYUCD) for critical comments and discussions.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM57249 (K.W.K.).

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://ajp.amjpathol.org or doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.014.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Kroemer G., Galluzzi L., Vandenabeele P., Abrams J., Alnemri E.S., Baehrecke E.H., Blagosklonny M.V., El-Deiry W.S., Golstein P., Green D.R., Hengartner M., Knight R.A., Kumar S., Lipton S.A., Malorni W., Nuñez G., Peter M.E., Tschopp J., Yuan J., Piacentini M., Zhivotovsky B., Melino G. Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2009: Classification of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2009. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:3–11. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams J.M., Cory S. The Bcl-2 protein family: arbiters of cell survival. Science. 1998;281:1322–1326. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pavlov E.V., Priault M., Pietkiewicz D., Cheng E.H., Antonsson B., Manon S., Korsmeyer S.J., Mannella C.A., Kinnally K.W. A novel, high conductance channel of mitochondria linked to apoptosis in mammalian cells and Bax expression in yeast. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:725–731. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dejean L.M., Martinez-Caballero S., Guo L., Hughes C., Teijido O., Ducret T., Ichas F., Korsmeyer S.J., Antonsson B., Jonas E.A., Kinnally K.W. Oligomeric Bax is a component of the putative cytochrome c release channel MAC, mitochondrial apoptosis-induced channel. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:2424–2432. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-12-1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez-Caballero S., Dejean L.M., Kinnally M.S., Oh K.J., Mannella C.A., Kinnally K.W. Assembly of the mitochondrial apoptosis-induced channel. MAC, J Biol Chem. 2009;284:12235–12245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806610200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dejean L.M., Martinez-Caballero S., Kinnally K.W. Is MAC the knife that cuts cytochrome c from mitochondria during apoptosis? Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1387–1395. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinnally K.W., Antonsson B. A tale of two mitochondrial channels, MAC and PTP, in apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2007;12:857–868. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0722-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cusato K., Bosco A., Rozental R., Guimarães C.A., Reese B.E., Linden R., Spray D.C. Gap junctions mediate bystander cell death in developing retina. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6413–6422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-16-06413.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cusato K., Ripps H., Zakevicius J., Spray D. Gap junctions remain open during cytochrome c-induced cell death: relationship of conductance to ‘bystander’ cell killing. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1707–1714. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cusato K., Zakevicius J., Ripps H. An experimental approach to the study of gap-junction-mediated cell death. Biol Bull. 2003;205:197–199. doi: 10.2307/1543250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burdak-Rothkamm S., Short S.C., Folkard M., Rothkamm K., Prise K.M. ATR-dependent radiation-induced gammaH2AX foci in bystander primary human astrocytes and glioma cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:993–1002. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koturbash I., Rugo R.E., Hendricks C.A., Loree J., Thibault B., Kutanzi K., Pogribny I., Yanch J.C., Engelward B.P., Kovalchuk O. Irradiation induces DNA damage and modulates epigenetic effectors in distant bystander tissue in vivo. Oncogene. 2006;25:4267–4275. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sedelnikova O.A., Nakamura A., Kovalchuk O., Koturbash I., Mitchell S.A., Marino S.A., Brenner D.J., Bonner W.M. DNA double-strand breaks form in bystander cells after microbeam irradiation of three-dimensional human tissue models. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4295–4302. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin J.H., Weigel H., Cotrina M.L., Liu S., Bueno E., Hansen A.J., Hansen T.W., Goldman S., Nedergaard M. Gap-junction-mediated propagation and amplification of cell injury [Erratum appeared in Nat Neurosci 1998;1:743] Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:494–500. doi: 10.1038/2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cotrina M.L., Kang J., Lin J.H., Bueno E., Hansen T.W., He L., Liu Y., Nedergaard M. Astrocytic gap junctions remain open during ischemic conditions. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2520–2537. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-07-02520.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang L., Bula D., Arroyo J.G., Chen D.F. Preventing retinal detachment-associated photoreceptor cell loss in Bax-deficient mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:648–654. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peixoto P.M., Ryu S.Y., Pruzansky D.P., Kuriakose M., Gilmore A., Kinnally K.W. Mitochondrial apoptosis is amplified through gap junctions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;390:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.09.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khodjakov A., Rieder C., Mannella C.A., Kinnally K.W. Laser micro-irradiation of mitochondria: is there an amplified mitochondrial death signal in neural cells? Mitochondrion. 2004;3:217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter A.D., Wroble B.N., Sible J.C. Cyclin A1/Cdk2 is sufficient but not required for the induction of apoptosis in early Xenopus laevis embryos. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2230–2236. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.19.3262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wroble B.N., Sible J.C. Chk2/Cds1 protein kinase blocks apoptosis during early development of Xenopus laevis. Dev Dyn. 2005;233:1359–1365. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nieuwkoop P.D., Faber J. ed 2. North Holland Publishing Company; Amsterdam: 1975. Normal table of Xenopus laevis. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter A.D., Sible J.C. Loss of XChk1 function triggers apoptosis after the midblastula transition in Xenopus laevis embryos. Mech Dev. 2003;120:315–323. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00443-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li F., Srinivasan A., Wang Y., Armstrong R.C., Tomaselli K.J., Fritz L.C. Cell-specific induction of apoptosis by microinjection of cytochrome c: Bcl-xL has activity independent of cytochrome c release. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30299–30305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhivotovsky B., Orrenius S., Brustugun O.T., Doskeland S.O. Injected cytochrome c induces apoptosis. Nature. 1998;391:449–450. doi: 10.1038/35060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peixoto P.M., Ryu S.Y., Pietkiewicz-Pruzansky D., Kuriakose M., Gilmore A., Kinnally K.W. Mitochondrial apoptosis is amplified through gap junctions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;390:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.09.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo L., Pietkiewicz D., Pavlov E.V., Grigoriev S.M., Kasianowicz J.J., Dejean L.M., Korsmeyer S.J., Antonsson B., Kinnally K.W. Effects of cytochrome c on the mitochondrial apoptosis-induced channel MAC. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C1109–C1117. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00183.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chipuk J.E., Kuwana T., Bouchier-Hayes L., Droin N.M., Newmeyer D.D., Schuler M., Green D.R. Direct activation of Bax by p53 mediates mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and apoptosis. Science. 2004;303:1010–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.1092734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cory S., Huang D.C., Adams J.M. The Bcl-2 family: roles in cell survival and oncogenesis. Oncogene. 2003;22:8590–8607. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Danial N.N., Korsmeyer S.J. Cell death: critical control points. Cell. 2004;116:205–219. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryu S.Y., Peixoto P.M., Teijido O., Dejean L.M., Kinnally K.W. Role of mitochondrial ion channels in cell death. Biofactors. 2010;36:255–263. doi: 10.1002/biof.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei M.C., Zong W.X., Cheng E.H., Lindsten T., Panoutsakopoulou V., Ross A.J., Roth K.A., MacGregor G.R., Thompson C.B., Korsmeyer S.J. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science. 2001;292:727–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1059108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finkielstein C.V., Lewellyn A.L., Maller J.L. The midblastula transition in Xenopus embryos activates multiple pathways to prevent apoptosis in response to DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1006–1011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson C.E., Freel C.D., Kornbluth S. Features of programmed cell death in intact Xenopus oocytes and early embryos revealed by near-infrared fluorescence and real-time monitoring. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:170–179. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Landesman Y., Goodenough D.A., Paul D.L. Gap junctional communication in the early Xenopus embryo. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:929–936. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.4.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guthrie S., Turin L., Warner A. Patterns of junctional communication during development of the early amphibian embryo. Development. 1988;103:769–783. doi: 10.1242/dev.103.4.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Das S., Nwachukwu J.C., Li D., Vulin A.I., Martinez-Caballero S., Kinnally K.W., Samuels H.H. The nuclear receptor interacting factor-3 transcriptional coregulator mediates rapid apoptosis in breast cancer cells through direct and bystander-mediated events. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1775–1782. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4034. [Erratum appeared in Cancer Res 2007;67:4535] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinez-Caballero S., Dejean L.M., Jonas E.A., Kinnally K.W. The role of the mitochondrial apoptosis induced channel MAC in cytochrome c release. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2005;37:155–164. doi: 10.1007/s10863-005-6570-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinez-Caballero S., Dejean L.M., Kinnally K.W. Some amphiphilic cations block the mitochondrial apoptosis-induced channel. MAC, FEBS Lett. 2004;568:35–38. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peixoto P.M., Ryu S.Y., Bombrun A., Antonsson B., Kinnally K.W. MAC inhibitors suppress mitochondrial apoptosis. Biochem J. 2009;423:381–387. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krutovskikh V.A., Piccoli C., Yamasaki H. Gap junction intercellular communication propagates cell death in cancerous cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:1989–1999. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.