Abstract

In the middle ear, a chain of three tiny bones (ie, malleus, incus, and stapes) vibrates to transmit sound from the tympanic membrane to the inner ear. Little is known about whether and how bone-resorbing osteoclasts play a role in the vibration of auditory ossicles. We analyzed hearing function and morphological features of auditory ossicles in osteopetrotic mice, which lack osteoclasts because of the deficiency of either cytokine RANKL or transcription factor c-Fos. The auditory brainstem response showed that mice of both genotypes experienced hearing loss, and laser Doppler vibrometry revealed that the malleus behind the tympanic membrane failed to vibrate. Histological analysis and X-ray tomographic microscopy using synchrotron radiation showed that auditory ossicles in osteopetrotic mice were thicker and more cartilaginous than those in control mice. Most interestingly, the malleal processus brevis touched the medial wall of the tympanic cavity in osteopetrotic mice, which was also the case for c-Src kinase–deficient mice (with normal numbers of nonresorbing osteoclasts). Osteopetrotic mice showed a smaller volume of the tympanic cavity but had larger auditory ossicles compared with controls. These data suggest that osteoclastic bone resorption is required for thinning of auditory ossicles and enlargement of the tympanic cavity so that auditory ossicles vibrate freely.

The temporal bone contains three highly mineralized bones [ie, the malleus (hammer), incus (anvil), and stapes (stirrup)].1 The malleus firmly attaches to the tympanic membrane and transmits vibration to the incus and stapes, which, in turn, vibrates fluid in the inner ear through the oval window.2 These auditory ossicles are arrayed in the middle ear, which is also called the tympanic cavity. Disturbances in sound transmission in the middle ear result in conductive hearing loss, whereas impairment of the internal ear or the auditory nerve causes sensorineural hearing loss.

Osteoclasts are specialized multinuclear macrophages that resorb bone. Once bones develop through endochondral and intramembranous ossification (bone modeling), osteoclastic bone resorption in adults is usually followed and balanced by osteoblastic bone formation through “coupling” mechanisms, which maintain bone integrity (bone remodeling).3 Turnover of temporal bones, including the otic capsule and auditory ossicles, is much slower than that of long bones because the former contain high levels of osteoprotegerin (OPG),4,5 a decoy receptor for the osteoclastogenic cytokine RANKL (a receptor activator of NF-κB ligand).6 Consistently, Opg−/− mice exhibit excessive numbers of osteoclasts because of increased RANKL activity and develop high-turnover osteoporosis.7 Auditory ossicles in Opg−/− mice are massively resorbed by abundant osteoclasts, resulting in impaired hearing function.8,9 In Opg−/− mice, the ligament at the junction of the stapes and the otic capsule is lost by bony ankylosis (fusion).8,9 The administration of the antiresorptive drug bisphosphonate prevents erosion of auditory ossicles and progression of hearing loss, demonstrating that excessive bone resorption underlies impaired hearing in Opg−/− mice.10

Conversely, a lack of or reduced osteoclastic bone resorption results in osteopetrosis in humans and rodents. Human osteopetrosis, first described in 1904 as “marble bone disease,” includes various inherited bone disorders marked by nonfunctional or poorly differentiated osteoclasts.11,12 Autosomal-recessive osteopetrosis is often severe and is usually seen in infants who show acidification deficiency of resorption lacunae. Recently, loss-of-function mutations in RANKL have been identified in patients with osteoclast-poor autosomal-recessive osteopetrosis.13 In contrast, autosomal-dominant osteopetrosis has a milder course and is often observed in adults with dominant-negative mutations in the chloride channel CLCN7. Conductive and sensorineural hearing loss is frequently seen in both autosomal-recessive and autosomal-dominant osteopetrosis and is reportedly due to mastoid obliteration, ossicular involvement, recurrent otitis media, or auditory nerve compression.14–17

In mice, osteopetrosis, which is characterized by the failure of tooth eruption and decreased bone marrow space, is observed after targeting of genes encoding RANKL (Tnfsf11 and Rankl), RANK (Tnfrsf11a), TRAF6 (Traf6), c-Fos (Fos), and c-Src (Src), among other factors.12 Macrophage colony-stimulating factor (Csf1) and RANKL are two cytokines crucial for osteoclast differentiation. The adaptor protein TRAF6 mediates RANK signaling, which eventually activates the transcription factors c-Fos and NF-κB. The c-Fos activates osteoclastogenic target genes, including Nfatc1, and is, therefore, essential for osteoclast differentiation.18,19 Naturally occurring loss-of-function mutations in the macrophage Csf gene cause osteopetrosis in Csf1op/op mice and toothless (tl/tl) rats.20,21 The Csf1op/op mice develop hearing loss attributed to abnormal brain development.22 The tl/tl rats show hearing loss and abnormalities in auditory ossicles, such as an increase in primitive calcified cartilage in the stapes and reduced capillary sprouting in the vascular bed of the temporal bone.23

In this study, we analyzed the morphological characteristics and mobility of auditory ossicles in mouse models of osteopetrosis. We show that bone resorption by osteoclasts is necessary for normal modeling of auditory ossicles and the temporal bone and provide an explanation for impaired vibration of auditory ossicles seen in osteopetrotic mice.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Mice lacking RANKL (Rankl−/−)24 and c-Src (Src−/−)25 were bred on a C57BL/6J background. Mice lacking c-Fos (Fos−/−)26 were produced by heterozygous breeding on a mixed C57BL/6J and 129 background. The Csf1op/op mice20 were obtained by heterozygous breeding on a mixed C57BL/6J and C3HeB/FeJ background. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with institutional board–approved protocols at Keio University, Tokyo, Japan; and the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology, Aichi, Japan.

Auditory Brainstem Response

A differential active needle electrode was placed subcutaneously below the pinna of the tested ear. A reference electrode was placed at the vertex, and a ground electrode was positioned below the pinna of the contralateral ear. The detailed procedure was previously described.9

Laser Doppler Vibrometry

A commercially available system (NLV-2500-5; Polytec Japan, Yokohama) was used for vibrometry. The sound stimulus from a speaker located near the ear canal was synchronized with the voltage output of the laser demodulator/controller. The 1.5-μm laser spot was positioned on the malleus, behind the tympanic membrane, under a charge-coupled, device–magnified image after the mouse head was immobilized and the ear lobes were removed under anesthesia. Mice were then exposed to continuous pure-tone stimuli of 2, 4, 12, and 20 kHz at sound pressure levels of 85, 94, 100, and 105 dB, respectively. Vibrations of the malleus were recorded and separated into various frequency components using fast Fourier transforms. Neither injury nor perforation of the tympanic membranes was observed after testing.

Microcomputed Tomographic Analysis

The skulls of Rankl−/−, Fos−/−, Src−/−, and control mice were imaged using microcomputed tomographic (μCT) scanners. A μCT scanner (R_mCT; Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was operated at 90 kV and 150 μA over 120 seconds. The CT images were reconstructed from 512 projections using computer software (i-view-R software; J. Morita, Kyoto, Japan). Reconstructed images were 481 × 481 × 481 pixels at a voxel size of 10 μm. In several experiments, a μCT scanner (model TDM1000; Yamato Scientific, Tokyo) was operated at 80 kV and 35 μ A using 16 integrations and 800 projections. Images were 1024 × 1024 × 1024 pixels at a voxel size of 4.93 μm. The three-dimensional (3D) data were analyzed using computer software (Tri/3D-BON software; Ratoc System Engineering, Tokyo). For volumetric analysis of wild-type and osteopetrotic mice, the limits of the tympanic cavity were defined as follows. The tympanic membrane forms the lateral wall, whereas the promontory (a part of the otic capsule) forms the medial wall. Superiorly, the tegmen tympani forms the roof; and, inferiorly, the bone over the jugular vein forms the floor of the middle ear. Because the tympanic cavity is continuous anteriorly with the Eustachian tube (auditory tube) and posteriorly with small cavities filled with air (mastoid air cells), we defined anterior and posterior limits of the tympanic cavity arbitrarily based on the anterior end of the malleus and the posterior end of the stapes, respectively, so that the entire array of ossicles is encased.

Biomicroscopy

The morphological characteristics of isolated auditory ossicles were analyzed using a stereoscopic zoom microscope with a digital camera system (Eclipse 90i, SMZ1500, Nikon, Tokyo).

Synchrotron X-Ray Tomographic Microscopy

Synchrotron radiation experiments were approved by the SPring-8 committee (2007B1787) and performed using a monochromatic X-ray beam (9.0 keV) at the beamline 20XU of the synchrotron radiation facility (SPring-8, for Super Photon ring-8GeV, Hyogo, Japan). The X-ray microscope was constructed using an X-ray Fresnel zone plate (ATN/FZP-S86/416; NTT-AT, Tokyo). The X-ray imaging optical magnification was 20.2. An X-ray image detector consisting of a charge-coupled device camera, a phosphor screen, and a coupling lens was used. Samples were placed 4 mm downstream from the on-focus position to enhance imaging of the edges of osteocyte lacunae and chondrocytes by defocus phase contrast. Through 180 degrees of sample rotation, 2000 images at 1344 × 1017 pixels were collected. Tomographic images were reconstructed at an effective voxel size of 0.22 μm. The 3D data were analyzed using computer software (Tri/3D-BON software).

Histological Analysis

The temporal bones were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 mol/L PBS. After washing with PBS, specimens were decalcified in 0.5 mol/L EDTA– (pH, 7.3) for 3 to 4 weeks at 4°C. Decalcified specimens were then washed in PBS, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanols, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with H&E, or Alcian Blue 8GX and Nuclear Fast Red.

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. We used the Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance with a confidence level of 95% using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 16 (IBM, Chicago, IL).

Results

Hearing Loss and Impaired Vibration of the Malleus

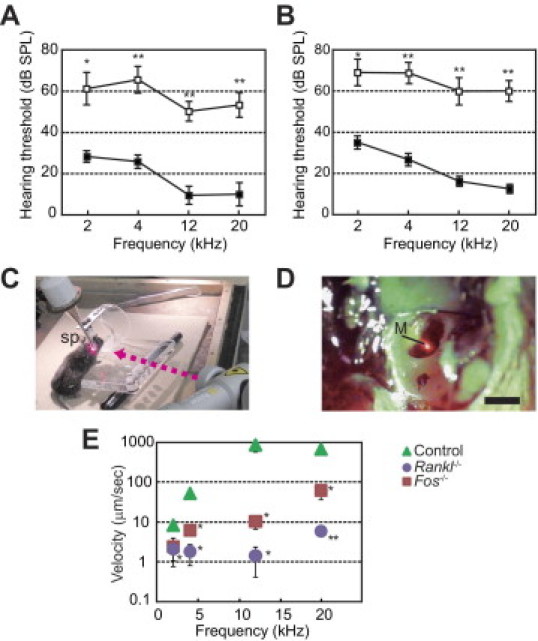

We first analyzed hearing function of osteopetrotic mice by measuring the auditory brainstem response. The hearing threshold of Rankl−/− mice was higher (worse) than that of wild-type control mice over the entire frequency range tested (2 to 20 kHz) (Figure 1A). A similar elevation in hearing threshold was observed in Fos−/− mice (Figure 1B). Although potential involvement of other cell types was not excluded, the similarity in phenotypes exhibited by these two strains of osteopetrotic mice suggested that the observed hearing loss is because of a lack of osteoclastic bone resorption.

Figure 1.

Hearing loss and impaired vibration of the malleus in osteopetrotic mice. A and B: Evaluation of the hearing threshold based on auditory brainstem response. Rankl−/− mice (A, open squares, aged 6 to 8 weeks, n = 6) and Fos−/− mice (B, open squares, aged 6 to 8 weeks, n = 6) were compared with wild-type controls (closed squares, aged 6 to 8 weeks, n = 6 for each). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001 versus wild-type controls. SPL indicates sound pressure level. C–E: Laser Doppler vibrometry. C: Picture of the experimental setting; sp, speaker. The pink arrow indicates the direction of the laser beam. D: The malleus (M) behind the tympanic membrane in a wild-type mouse targeted with the laser beam. E: Velocity of the vibrating malleus in littermate controls (n = 5), Rankl−/− mice (aged 17 weeks, n = 2), and Fos−/− mice (aged 10 to 14 weeks, n = 3) exposed to pure-tone sounds at 2, 4, 12, and 20 kHz. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 versus controls.

To determine whether the mobility of auditory ossicles was affected in Rankl−/− and Fos−/− mice, we monitored the vibration of the malleus behind the tympanic membrane using laser Doppler vibrometry. After immobilizing the head of control or mutant mice, a rod-type speaker was placed near the exposed tympanic membrane (Figure 1C). The laser beam was targeted to the malleus, which was clearly visible behind the tympanic membrane (Figure 1D). Based on the maximum velocity of the malleus, the tympanic membranes of control mice responded well to pure-tone sounds at 12 and 20 kHz and less prominently to stimuli at 2 and 4 kHz (Figure 1E). In contrast, the vibration of the malleus of Rankl−/− and Fos−/− mice was significantly impaired. The velocities of the malleus for control, Rankl−/−, and Fos−/− mice at pure-tone stimuli of 12 kHz were 670, 1.4, and 10 μm/s (Figure 1E), corresponding to amplitudes of 8.9 ± 1.3, 0.14 ± 0.05, and 0.02 ± 0.01 nm, respectively. These data suggest that osteoclastic bone resorption is required for auditory ossicles to be able to vibrate.

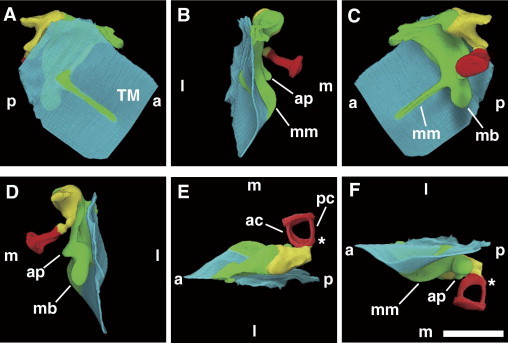

Morphological Characteristics of Wild-Type Auditory Ossicles

Next, we visualized the chain of auditory ossicles of wild-type mice using μCT. Reconstructed images shown in Figure 2 indicate that the head of the malleus (green) articulated with the body of the incus (yellow), which connected through its long process with the stapes (red). The handle of the murine malleus (malleal manubrium) was attached to the tympanic membrane and was winglike (Figure 2, A, B, and F). The characteristic semispherical process of the murine malleus, called the malleal processus brevis (short process), did not contact the tympanic membrane (Figure 2, C and D), although a conical projection that constitutes the human equivalent of the processus brevis (also called processus lateralis) reportedly attaches to the tympanic membrane.27 As expected, the anterior process of the malleus ran anteriorly (Figure 2, D and F). The morphological features of the murine stapes (Figure 2, E and F) were grossly similar to those known for the human stapes.27 On the posterior crus of the stapes, the tubercle for the insertion of the stapedius muscle, which damps down excess vibration of the stapes, was visible (Figure 2, E and F).

Figure 2.

The μCT imaging of the right auditory ossicles of 8-week-old wild-type mice. A–D: Rotating views of wild-type auditory ossicles presented in pseudocolors: malleus (green), incus (yellow), stapes (red), and tympanic membrane (TM; blue). Lateral (l) (A), anterior (a) (B), medial (m) (C), and posterior (p) (D) images are shown; ap, anterior process; mb, malleal processus brevis; mm, malleal manubrium. Superior (E) and inferior (F) views; ac, anterior crus; pc, posterior crus; asterisks indicate a tubercle for stapedius muscle insertion. The voxel size was originally 4.93 μm and was downsized to 9.86 μm. Scale bar = 1 mm.

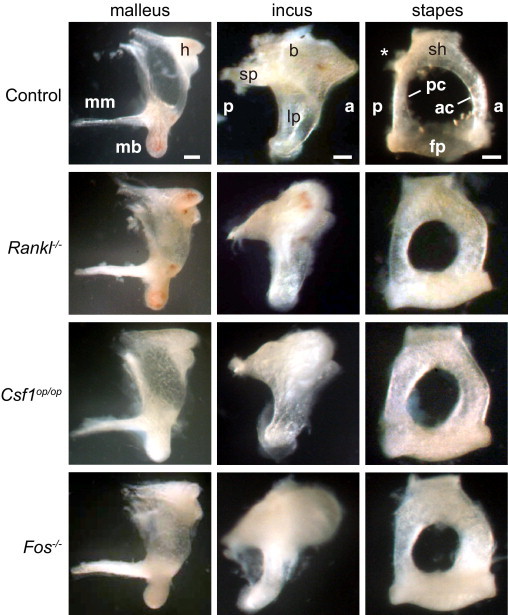

Osteopetrotic Auditory Ossicles Show Aberrant Thickening

We isolated the malleus, incus, and stapes from control mice and three lines of osteopetrotic mice (ie, Rankl−/−, Csf1op/op, and Fos−/−). Auditory ossicles in osteopetrotic mice were similar in overall morphological features to those seen in control mice, except that osteopetrotic ossicles were thicker, particularly at the malleal manubrium, incus body, and stapedial arch (especially the anterior and posterior crura) than control ossicles (Figure 3). Because of the thick crura, the space between the crura (the obturator foramen) through which the stapedial artery passes (Figure 4E) was smaller in osteopetrotic compared with control mice (Figure 3, right). These morphological changes in auditory ossicles suggest that in wild-type mice osteoclasts function to resorb the surface of ossicles, thereby paring them down.

Figure 3.

Morphological characteristics of auditory ossicles in control, Rankl−/−, Csf1op/op, and Fos−/− mice (aged 6 to 8 weeks). Scale bar = 250 μm for the malleus and 100 μm for the incus and stapes. h, head; mb, malleal processus brevis; mm, malleal manubrium; b, body; sp, short process; lp, long process; sh, stapedial head; ac, anterior crus; pc, posterior crus; fp, floor plate; asterisk indicates a tubercle for stapedius muscle insertion.

Figure 4.

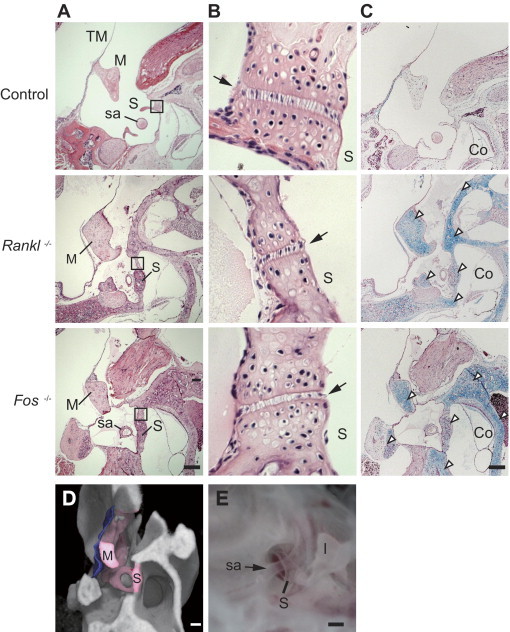

Histological analysis of the middle ear of control, Rankl−/−, and Fos−/− mice (aged 6 to 8 weeks). A: H&E staining. B: Higher magnification of the stapedial-cochlear junction shown in the boxed area of A. Arrows indicate the ligament between the stapedial footplate and the cochlea. C: Staining (Alcian Blue) of cartilage with Nuclear Fast Red counterstaining. Arrowheads indicate cartilage. D: Pseudocolored μCT image of Fos−/− mice sectioned in silico, as in A. The auditory ossicles (pink) and tympanic membrane (blue) are visible. E: Binocular image of the stapedial artery passing through the stapes in a wild-type mouse. TM, tympanic membrane; M, malleus; I, incus; S, stapes; sa, stapedial artery; Co, cochlea. Scale bar = 200 μm.

Osteopetrotic Mice Exhibit Chondrocytes in Auditory Ossicles and Temporal Bone

Next, we histologically analyzed stapedial-cochlear junctions in control, Rankl−/−, and Fos−/− mice because bony fusion of the stapedial-cochlear junction is observed as an otosclerosis-like phenotype in Opg−/− mice9 and is similar to so-called stapes fixation in human otosclerosis associated with conductive hearing loss. However, in both Rankl−/− and Fos−/− mice, the ligament between the stapedial footplate and the otic capsule appeared to be intact (Figure 4, A and B). On the other hand, cartilaginous tissues were observed in both auditory ossicles and the temporal bone in Rankl−/− and Fos−/− mice. Staining (Alcian Blue) of cartilage on an adjacent section confirmed abundant chondrocytes in mutant compared with control mice in all three ossicles and in the otic capsule surrounding the base of the cochlea (Figure 4C, open arrowheads). A μCT image of a Fos−/− mouse was sliced in silico along the same plane as histological sections revealing the anatomical relationship between the stapedial artery and the stapes (Figure 4, A and D). The stapedial artery passing through the stapes was directly confirmed by binocular microscopy (Figure 4E).

3D Analysis of Cartilage in the Malleal Processus Brevis of Fos−/− Mice

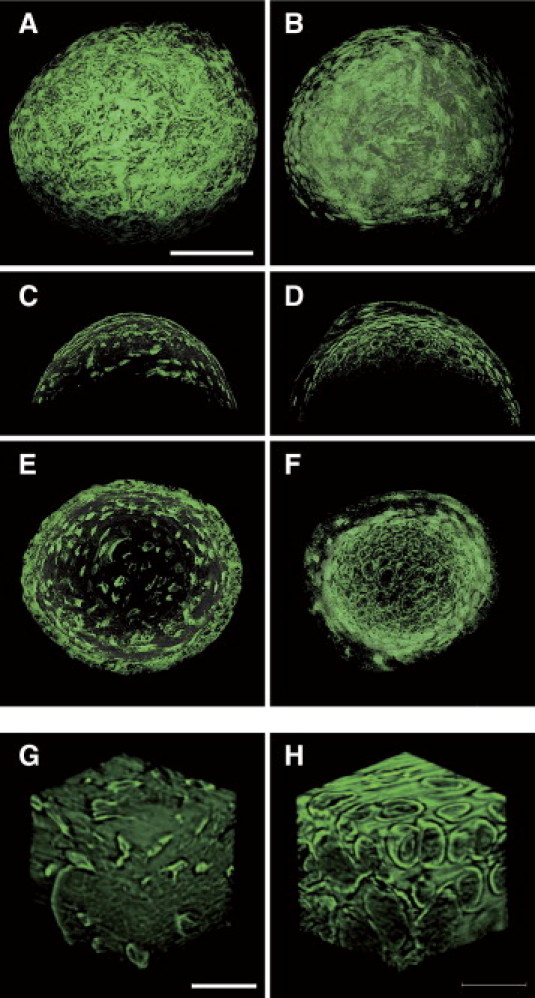

Unlike bone, cartilage is difficult to visualize in conventional μCT because of the low X-ray absorption. Therefore, we performed high-resolution 3D analysis of the malleus processus brevis of wild-type and Fos−/− mice using X-ray tomographic microscopy with synchrotron radiation, which allows imaging of chondrocytes. We focused on the malleal processus brevis, a semispherical protrusion of unknown function with a diameter of approximately 300 μm.28 The 3D reconstruction and analysis of vertical and horizontal sections of the processus brevis of control mice revealed bone tissue containing osteocytic lacunae (Figure 5, A, C, E, and G). In contrast, the malleal processus brevis of Fos−/− mice contained hypertrophic chondrocytes (Figure 5, B, D, F, and H). Characteristically large, round, and paired chondrocytes, as observed in articular cartilage,29 were clearly visible (Figure 5H). The malleal processus brevis of Traf6−/− mice was also filled with paired chondrocytes based on analysis using synchrotron X-ray tomographic microscopy (data not shown). These data suggest that the malleal processus brevis of osteoclast-deficient mice remains cartilaginous because proper endochondral ossification does not occur in the absence of osteoclastic bone resorption.

Figure 5.

Synchrotron tomographic microscopic imaging of the malleal processus brevis. A, C, E, and G: Representative images of 31-week-old wild-type mice. B, D, F, and H: Representative images of 36-week-old Fos−/− mice. The 3D images of the tip of the malleal processus brevis (A and B), with in silico vertical (C and D) or horizontal (E and F) sections. Scale bar = 100 μm. Internal 30-μm cubes for each genotype are shown in G and H, respectively. Scale bar = 20 μm. G: At least nine osteocyte lacunae. H: At least six paired chondrocytes. The voxel size was 0.22 μm.

Malleus Contacts the Middle Ear Wall in Osteopetrotic Mice

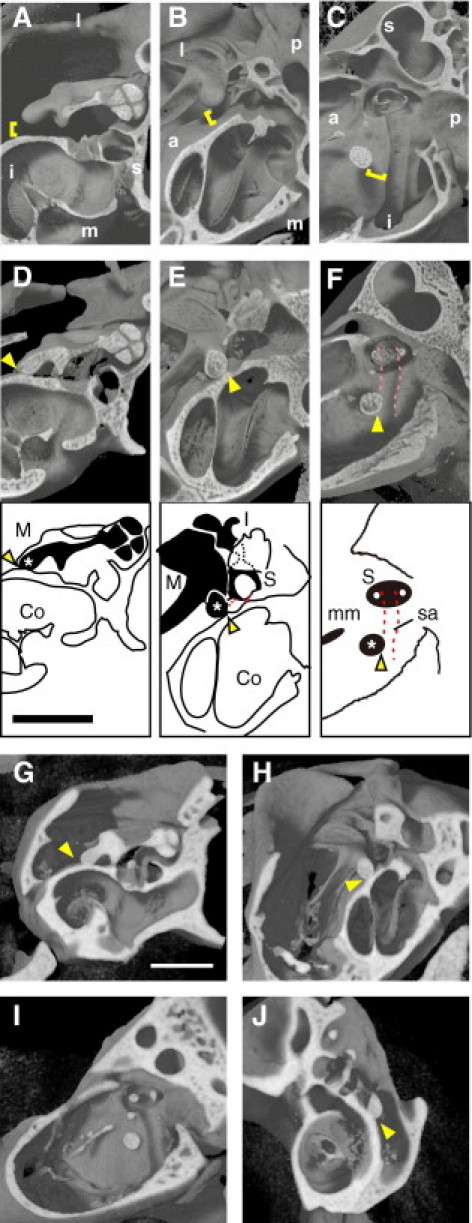

To gain insight into the cause of impaired vibration of auditory ossicles, we compared conventional μCT images of the middle ear of wild-type and Fos−/− mice. As expected, a wild-type mouse showed detachment of the malleal processus brevis from the walls of the tympanic cavity and from the path of the stapedial artery on the medial wall of the tympanic cavity (Figure 6, A–C). Unexpectedly, however, the malleal processus brevis of a Fos−/− mouse was in contact with the medial wall of the tympanic cavity (the promontory or lateral wall of the cochlea) (Figure 6, D and E). Furthermore, the processus brevis overlapped with the path of the stapedial artery (Figure 6F). Similar contact of the malleus to temporal bone or to the path of the stapedial artery was evident in three other Fos−/− mice evaluated at the age of 31 to 36 weeks (see Supplemental Figure S1, A–F, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Next, we analyzed phenotypes in younger Fos−/− mice and found that in both 16- and 4-week-old Fos−/− mice the malleal processus brevis was compressed against the promontory (see Supplemental Figure S1, G–J, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Figure 6.

The μCT imaging of morphological defects associated with the Fos−/− and Src−/− middle ear. The wild-type malleal processus brevis was detached from the middle ear wall (brackets), whereas the Fos−/− and Src−/− malleal processus brevis contacted the wall (arrowheads). A through C: Wild-type mouse (aged 8 weeks). D through F:Fos−/− mouse (aged 8 weeks). Schematic representations of auditory ossicles (black) and surrounding bone (white) in D through F are shown. M indicates malleus; (in malleus) an asterisk marks the malleal processus brevis; Co, cochlea; S, stapes; sa, stapedial artery; mm, malleal manubrium. Dashed pink (red) lines indicate the path of the stapedial artery. G through J:Src−/− mouse (aged 56 weeks). A, D, and G: Posterior views. B, E, and H: Interior views. C, F, and I: Lateral views. J: Anterior view. Scale bar = 1 mm. l indicates lateral; m, medial; s, superior; i, inferior; a, anterior; p, posterior. The voxel size was 4.93 μm (A–F) and 10 μm (G–J).

Next, we examined the middle ear of osteopetrotic mice lacking the c-Src proto-oncogene.25 In contrast to Fos−/− mice, which completely lack osteoclasts, Src−/− mice exhibit ample osteoclasts; however, these cells do not form sealing ring, which is required for them to adhere to and resorb bone.25 The μCT analysis showed that the malleal processus brevis was pressed against the medial wall of the tympanic cavity in Src−/− mice (Figure 6, G–J). These data indicate that bone resorption activity is essential for auditory ossicles to be suspended in the middle ear cavity without touching the wall.

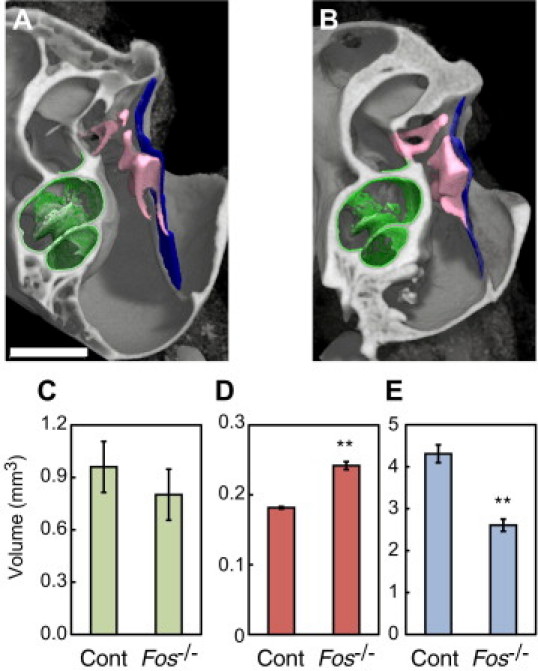

Osteopetrotic Mice Exhibit Reduced Middle Ear Space and Increased Auditory Ossicle Volume

Next, we quantified the volume of auditory ossicles in wild-type and Fos−/− osteopetrotic mice by extracting the malleus, incus, and stapes from binarized μCT images (Figure 7, A and B, pink). The tympanic membrane (blue) and cochlea (green) were also extracted and pseudocolored. Although the volume of the cochlea did not differ significantly between control and Fos−/− mice (Figure 7C), the volume of auditory ossicles was greater (Figure 7D) and the volume of the tympanic cavity was smaller in Fos−/− mice compared with control mice (Figure 7E). These data strongly suggest that osteoclastic bone resorption is essential to enlarge the tympanic cavity, which encases auditory ossicles, allowing them to vibrate freely.

Figure 7.

Volumes of the inner ear, auditory ossicles, and middle ear of control (Cont) and Fos−/− osteopetrotic mice. A and B: Pseudocolored μCT images indicating the cochlea (green), auditory ossicles (pink), and tympanic membrane (blue) of control (A) and Fos−/− mice (B). The voxel size was 10 μm. C: Volume of the cochlea. D: Volume of the auditory ossicles. E: Volume of the tympanic cavity. Adult (aged 31 to 36 weeks) male mice were used for quantification (n = 3 for each genotype; see Supplemental Figure S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). **P < 0.01 versus controls.

Discussion

A striking finding of this study is that the malleus in osteopetrotic mice contacts the wall of the tympanic cavity, preventing auditory ossicles from vibrating and leading to hearing loss. This abnormal contact is likely because of the increased volume of auditory ossicles and the reduced volume of the tympanic cavity in osteopetrotic mice.

The otic capsule expresses high levels of OPG, which suppresses osteoclastogenesis,4,5 suggesting that the absence of osteoclastic bone resorption might not significantly affect the middle ear. However, the middle ear of osteopetrotic mice was significantly altered both morphologically and functionally. Curiously, various parts of the auditory ossicles, including the stapedial crura, were thicker in osteopetrotic mice than in controls, indicating that osteoclasts sculpt auditory ossicles at the perichondrium or periosteum when the cartilage anlagen is replaced by bone. The precise mechanisms by which the boundary of auditory ossicles is modeled by osteoclast-dependent processes are not known. Because auditory ossicles and the wall of the tympanic cavity are exceptional in that the bone surface is exposed to air, additional mechanisms might maintain and remodel the surfaces of these bones.

Auditory ossicles are formed through endochondral ossification,30 and the persistence of cartilage in auditory ossicles and the otic capsule indicates that resorption of hypertrophic chondrocytes by osteoclasts is critical to replace cartilage with bone. Indeed, synchrotron X-ray microscopy revealed that the semispherical processus brevis of the malleus in adult Fos−/− mice was composed exclusively of chondrocytes, except for a superficial perichondral layer.

The malleal processus brevis of osteopetrotic mice is reminiscent of the growth plate of a long bone, which is avascular and is eventually resorbed by osteoclasts. In the absence of osteoclasts, hypertrophic chondrocytes in the growth plate accumulate, even in the presence of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase-negative “chondroclasts,” which express matrix metalloproteinase 9 (also known as gelatinase B).31 The matrix metalloproteinases and vascular endothelial growth factor are key regulators of growth plate angiogenesis and hypertrophic chondrocyte apoptosis.32,33 Future studies should address their roles in modeling of auditory ossicles and the otic capsule. Even in the absence of osteoclasts, the diaphysis of long bones allows blood vessel invasion.26,34 Whether and where osteoclast-independent mechanisms promoting ingrowth of blood vessels into the cartilaginous anlagen of auditory ossicles exist is a topic for future investigation.

Both Rankl−/− and Fos−/− mice showed significantly higher hearing thresholds than did control mice in auditory brainstem responses. In most middle ear diseases, including chronic otitis media and otosclerosis, the ossicles cannot transmit sound vibration. Stapedial ankylosis or otosclerosis-like changes have been reported in human osteopetrosis.35 However, our histological analysis in osteopetrotic mice suggests that the stapedial footplate ligaments were intact and that there was no detectable fusion of the stapes footplate to the oval window. Persistence of chondrocytes in ossicles of osteopetrotic mice may impair hearing function because of insufficient stiffness of the ossicles; however, there are few data to support this hypothesis. Because hearing loss in human recessive osteopetrosis is usually conductive,14 we hypothesized that sound-induced stapes velocity may be impaired. Although stapes velocity has been measured using laser Doppler vibrometry in human patients undergoing cochlear implantation,36 measurement of stapes mobility in live mice is technically difficult. Therefore, we analyzed the mobility of the malleus behind the tympanic membrane noninvasively by using highly sensitive single-point laser Doppler vibrometry. Recently, it was reported that laser Doppler vibrometry can be used to detect middle ear anomalies in mice.37 In the present study, we observed dramatically reduced mobility of the malleus behind the tympanic membrane in mice lacking c-Fos or RANKL. Although we cannot formally exclude involvement of the nervous system, impaired vibration of the malleus behind the tympanic membrane is the most plausible explanation for hearing loss in osteopetrotic mice. Impaired vibration was apparently caused by contact of the malleus to the promontory, together with reduced volume of the tympanic cavity and increased volume of the auditory ossicles.

We have shown that osteoclastic bone resorption regulates the shape and function of auditory ossicles and the surrounding bone. Further studies of these tiny bones would enhance understanding of their specialized roles in hearing and the biological basis of morphogenesis in endochondral bone formation beyond auditory ossicles.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kyoichi Emi for providing a method to immobilize mouse heads during vibrometry; Yoshio Suzuki, Akihisa Takeuchi, and Gen-ichiro Sano for providing technical help with X-ray tomographic microscopy; and Elise Lamar for proofreading.

Footnotes

Supported by Grants-in-Aid for Young Scientists B (17791198 and 21791643 to S.K.) and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research B (17390420 and 21390425 to K.M. and 19360027 to A.M.) from JSPS; and a Keio University Special Grant-in-Aid for Innovative Collaborative Research Projects.

S.K. and Ya.T. contributed equally to this work.

Ya.T. is employed by Rigaku Corporation, and N.N. is employed by Ratoc System Engineering Co, Ltd.; products from both companies were used in this work.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://ajp.amjpathol.org or at doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.063.

Current address of Ya.T.: Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan.

Supplementary data

The μCT imaging of auditory ossicles in the middle ear of Fos−/− mice. A through F: Control (A+/−, B+/+, and C+/−) and osteopetrotic (D−/−, E−/−, and F−/−) mice (male, aged 31 to 36 weeks) were obtained from mating of Fos+/− mice. Top panels: Lateral view of the middle ear cut on a parasagittal plane through the malleal processus brevis. The yellow arrowheads indicate malleal processus brevis in contact with the path of the stapedial artery. Lower panels: Inferior view of the middle ear cut on a horizontal plane through the malleal processus brevis. The yellow arrowheads indicate the malleal processus brevis in contact with the medial wall of the tympanic cavity (ie, the lateral wall of the cochlea). G through J: Inferior view of the middle ear cut on a horizontal plane through the malleal processus brevis. Wild-type mice (aged 4 weeks [G] and 16 weeks [H]) and Fos−/− mice (aged 4 weeks [I] and 16 weeks [J]) were used. The yellow arrowheads indicate the malleal processus brevis in contact with the medial wall of the tympanic cavity (ie, the lateral wall of the cochlea). Figure 5 has a more detailed description of structures. Scale bar = 1 mm.

References

- 1.Currey J.D. How well are bones designed to resist fracture? J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:591–598. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.4.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frolenkov G.I., Belyantseva I.A., Friedman T.B., Griffith A.J. Genetic insights into the morphogenesis of inner ear hair cells. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:489–498. doi: 10.1038/nrg1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao C., Irie N., Takada Y., Shimoda K., Miyamoto T., Nishiwaki T., Suda T., Matsuo K. Bidirectional ephrinB2-EphB4 signaling controls bone homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2006;4:111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zehnder A.F., Kristiansen A.G., Adams J.C., Merchant S.N., McKenna M.J. Osteoprotegerin in the inner ear may inhibit bone remodeling in the otic capsule. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:172–177. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000150702.28451.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stankovic K.M., Adachi O., Tsuji K., Kristiansen A.G., Adams J.C., Rosen V., McKenna M.J. Differences in gene expression between the otic capsule and other bones. Hear Res. 2010;265:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kearns A.E., Khosla S., Kostenuik P.J. Receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand and osteoprotegerin regulation of bone remodeling in health and disease. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:155–192. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bucay N., Sarosi I., Dunstan C.R., Morony S., Tarpley J., Capparelli C., Scully S., Tan H.L., Xu W., Lacey D.L., Boyle W.J., Simonet W.S. Osteoprotegerin-deficient mice develop early onset osteoporosis and arterial calcification. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1260–1268. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.9.1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zehnder A.F., Kristiansen A.G., Adams J.C., Kujawa S.G., Merchant S.N., McKenna M.J. Osteoprotegrin knockout mice demonstrate abnormal remodeling of the otic capsule and progressive hearing loss. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:201–206. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000191466.09210.9a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanzaki S., Ito M., Takada Y., Ogawa K., Matsuo K. Resorption of auditory ossicles and hearing loss in mice lacking osteoprotegerin. Bone. 2006;39:414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.01.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanzaki S., Takada Y., Ogawa K., Matsuo K. Bisphosphonate therapy ameliorates hearing loss in mice lacking osteoprotegerin. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:43–49. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Del Fattore A., Cappariello A., Teti A. Genetics, pathogenesis and complications of osteopetrosis. Bone. 2008;42:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tolar J., Teitelbaum S.L., Orchard P.J. Osteopetrosis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2839–2849. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sobacchi C., Frattini A., Guerrini M.M., Abinun M., Pangrazio A., Susani L., Bredius R., Mancini G., Cant A., Bishop N., Grabowski P., Del Fattore A., Messina C., Errigo G., Coxon F.P., Scott D.I., Teti A., Rogers M.J., Vezzoni P., Villa A., Helfrich M.H. Osteoclast-poor human osteopetrosis due to mutations in the gene encoding RANKL. Nat Genet. 2007;39:960–962. doi: 10.1038/ng2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawke M., Jahn A.F., Bailey D. Osteopetrosis of the temporal bone. Arch Otolaryngol. 1981;107:278–282. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1981.00790410016003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stocks R.M., Wang W.C., Thompson J.W., Stocks M.C., 2nd, Horwitz E.M. Malignant infantile osteopetrosis: otolaryngological complications and management. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:689–694. doi: 10.1001/archotol.124.6.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benichou O.D., Laredo J.D., de Vernejoul M.C. Type II autosomal dominant osteopetrosis (Albers-Schon̈berg disease): clinical and radiological manifestations in 42 patients. Bone. 2000;26:87–93. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(99)00244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maranda B., Chabot G., Décarie J.C., Pata M., Azeddine B., Moreau A., Vacher J. Clinical and cellular manifestations of OSTM1-related infantile osteopetrosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:296–300. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.071015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuo K., Owens J.M., Tonko M., Elliott C., Chambers T.J., Wagner E.F. Fosl1 is a transcriptional target of c-Fos during osteoclast differentiation. Nat Genet. 2000;24:184–187. doi: 10.1038/72855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuo K., Galson D.L., Zhao C., Peng L., Laplace C., Wang K.Z., Bachler M.A., Amano H., Aburatani H., Ishikawa H., Wagner E.F. Nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) rescues osteoclastogenesis in precursors lacking c-Fos. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:26475–26480. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313973200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshida H., Hayashi S., Kunisada T., Ogawa M., Nishikawa S., Okamura H., Sudo T., Shultz L.D. The murine mutation osteopetrosis is in the coding region of the macrophage colony stimulating factor gene. Nature. 1990;345:442–444. doi: 10.1038/345442a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Wesenbeeck L., Odgren P.R., MacKay C.A., D'Angelo M., Safadi F.F., Popoff S.N., Van Hul W., Marks S.C., Jr The osteopetrotic mutation toothless (tl) is a loss-of-function frameshift mutation in the rat Csf1 gene: evidence of a crucial role for CSF-1 in osteoclastogenesis and endochondral ossification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14303–14308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202332999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michaelson M.D., Bieri P.L., Mehler M.F., Xu H., Arezzo J.C., Pollard J.W., Kessler J.A. CSF-1 deficiency in mice results in abnormal brain development. Development. 1996;122:2661–2672. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aharinejad S., Grossschmidt K., Franz P., Streicher J., Nourani F., MacKay C.A., Firbas W., Plenk H., Jr, Marks S.C., Jr Auditory ossicle abnormalities and hearing loss in the toothless (osteopetrotic) mutation in the rat and their improvement after treatment with colony-stimulating factor-1. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:415–423. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.3.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kong Y.Y., Yoshida H., Sarosi I., Tan H.L., Timms E., Capparelli C., Morony S., Oliveira-dos-Santos A.J., Van G., Itie A., Khoo W., Wakeham A., Dunstan C.R., Lacey D.L., Mak T.W., Boyle W.J., Penninger J.M. OPGL is a key regulator of osteoclastogenesis, lymphocyte development and lymph-node organogenesis. Nature. 1999;397:315–323. doi: 10.1038/16852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soriano P., Montgomery C., Geske R., Bradley A. Targeted disruption of the c-src proto-oncogene leads to osteopetrosis in mice. Cell. 1991;64:693–702. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90499-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grigoriadis A.E., Wang Z.Q., Cecchini M.G., Hofstetter W., Felix R., Fleisch H.A., Wagner E.F. c-Fos: a key regulator of osteoclast-macrophage lineage determination and bone remodeling. Science. 1994;266:443–448. doi: 10.1126/science.7939685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gray H. External and Middle Ear. In: Standring S., editor. GRAY'S anatomy: The anatomical basis of clinical practice. ed 40. Churchill-Livingstone; London: 2008. pp. 615–631. ch 38. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Z., Zhang X., Avniel W.A., Song Y., Jones S.M., Jones T.A., Fermin C., Chen Y. Malleal processus brevis is dispensable for normal hearing in mice. Dev Dyn. 2003;227:69–77. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chi S.S., Rattner J.B., Matyas J.R. Communication between paired chondrocytes in the superficial zone of articular cartilage. J Anat. 2004;205:363–370. doi: 10.1111/j.0021-8782.2004.00350.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tucker A.S., Watson R.P., Lettice L.A., Yamada G., Hill R.E. Bapx1 regulates patterning in the middle ear: altered regulatory role in the transition from the proximal jaw during vertebrate evolution. Development. 2004;131:1235–1245. doi: 10.1242/dev.01017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ortega N., Wang K., Ferrara N., Werb Z., Vu T.H. Complementary interplay between matrix metalloproteinase-9, vascular endothelial growth factor and osteoclast function drives endochondral bone formation. Dis Model Mech. 2010;3:224–235. doi: 10.1242/dmm.004226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vu T.H., Shipley J.M., Bergers G., Berger J.E., Helms J.A., Hanahan D., Shapiro S.D., Senior R.M., Werb Z. MMP-9/gelatinase B is a key regulator of growth plate angiogenesis and apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes. Cell. 1998;93:411–422. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81169-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerber H.P., Vu T.H., Ryan A.M., Kowalski J., Werb Z., Ferrara N. VEGF couples hypertrophic cartilage remodeling, ossification and angiogenesis during endochondral bone formation. Nat Med. 1999;5:623–628. doi: 10.1038/9467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maes C., Kobayashi T., Selig M.K., Torrekens S., Roth S.I., Mackem S., Carmeliet G., Kronenberg H.M. Osteoblast precursors, but not mature osteoblasts, move into developing and fractured bones along with invading blood vessels. Dev Cell. 2010;19:329–344. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dozier T.S., Duncan I.M., Klein A.J., Lambert P.R., Key L.L., Jr Otologic manifestations of malignant osteopetrosis. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26:762–766. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000178139.27472.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chien W., Rosowski J.J., Ravicz M.E., Rauch S.D., Smullen J., Merchant S.N. Measurements of stapes velocity in live human ears. Hear Res. 2009;249:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qin Z., Wood M., Rosowski J.J. Measurement of conductive hearing loss in mice. Hear Res. 2010;263:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The μCT imaging of auditory ossicles in the middle ear of Fos−/− mice. A through F: Control (A+/−, B+/+, and C+/−) and osteopetrotic (D−/−, E−/−, and F−/−) mice (male, aged 31 to 36 weeks) were obtained from mating of Fos+/− mice. Top panels: Lateral view of the middle ear cut on a parasagittal plane through the malleal processus brevis. The yellow arrowheads indicate malleal processus brevis in contact with the path of the stapedial artery. Lower panels: Inferior view of the middle ear cut on a horizontal plane through the malleal processus brevis. The yellow arrowheads indicate the malleal processus brevis in contact with the medial wall of the tympanic cavity (ie, the lateral wall of the cochlea). G through J: Inferior view of the middle ear cut on a horizontal plane through the malleal processus brevis. Wild-type mice (aged 4 weeks [G] and 16 weeks [H]) and Fos−/− mice (aged 4 weeks [I] and 16 weeks [J]) were used. The yellow arrowheads indicate the malleal processus brevis in contact with the medial wall of the tympanic cavity (ie, the lateral wall of the cochlea). Figure 5 has a more detailed description of structures. Scale bar = 1 mm.