Abstract

Background:

Classic methods of identifying genes involved in neural function include the laborious process of behavioral screening of mutagenized flies and then rescreening candidate lines for pleiotropic effects due to developmental defects. To accelerate the molecular analysis of brain function in Drosophila we constructed a cDNA library exclusively from adult brains. Our goal was to begin to develop a catalog of transcripts expressed in the brain. These transcripts are expected to contain a higher proportion of clones that are involved in neuronal function.

Results:

The library contains approximately 6.75 million independent clones. From our initial characterization of 271 randomly chosen clones, we expect that approximately 11% of the clones in this library will identify transcribed sequences not found in expressed sequence tag databases. Furthermore, 15% of these 271 clones are not among the 13,601 predicted Drosophila genes.

Conclusions:

Our analysis of this unique Drosophila brain library suggests that the number of genes may be underestimated in this organism. This work complements the Drosophila genome project by providing information that facilitates more complete annotation of the genomic sequence. This library should be a useful resource that will help in determining how basic brain functions operate at the molecular level.

Background

Drosophila melanogaster is an important model organism. After more than 50 years of study, the anatomy of the brain is well described and many brain functions have been mapped to particular substructures [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. The adult brain is composed of approximately 200,000 neurons which are organized into discrete substructures. The optic lobe (composed of the lamina, medulla, lobula and lobula plate) is primarily involved in the processing of visual information from the photoreceptors and sending that information to the central brain [2,5,9]. The antennal lobes are chiefly responsible for the processing of olfactory information [10]. The mushroom bodies are involved in olfactory learning and memory and other complex behaviors [11,12,13,14,15]. A group of approximately six neurons in the lateral protocerebrum are sufficient to drive circadian rhythms in locomoter activity [16,17]. The central complex, although poorly understood, appears to be involved in motor coordination [18,19,20].

Despite our increasing knowledge of Drosophila brain anatomy and function, relatively little information is available concerning the molecules expressed in the brain that coordinate function and manifest behavior. Classic methods of identifying genes involved in neural function include behavioral screening of mutagenized flies, then rescreening candidate lines for pleiotropic effects due to developmental defects. This process is both laborious and time consuming. To augment this genetic approach, sequencing of random cDNAs is proving effective in identifying genes expressed in a specific cell type [21]. Much information has been collected through the analysis of expressed sequence tags (ESTs) [22,23,24,25]. Using this approach, sequence information is gathered from one or both ends of a cDNA and cataloged to determine the complexity of an mRNA population. Here, we use a modified EST approach and completely sequence novel cDNAs. Others have used a similar approach by shotgun sequencing concatenated cDNA inserts [26,27]. One goal of our work was to begin to develop a catalog of transcripts expressed in the brain. These transcripts, because of the location of their expression, are expected to contain a higher proportion of clones that are involved in neuronal function.

Many Drosophila head libraries have been used to isolate cDNAs that correspond to genes identified by genetic screens for their involvement in brain function. Several transcripts identified in this manner are expressed at a relatively low level (dunce [28], CREB [29], dco [30], period [31], timeless [32], dissonance [33]). The Drosophila brain makes up only a small part of head tissue (approximately 14% dry weight). By eliminating non-brain tissues, we increase the relative representation of rare neural transcripts in this unique library.

We began a catalog of the genes expressed in the brain of adult Drosophila in support of more conventional methods of understanding brain function. Cataloging sequence information and publishing the data through electronic databases has enriched molecular science in general. In a matter of a few minutes, one can use information from a single sequencing reaction to identify a gene that was sequenced by another laboratory, and one maybe able to deduce the function of the isolated clone. This set of tools facilitates molecular work in virtually every branch of biological sciences. This report details construction, quality analysis and initial characterization of a unique library created from adult Drosophila brains. Surprisingly, we discovered that 11% (29 clones) of the Drosophila brain cDNA clones that were randomly chosen for analysis are not matched with any EST sequence generated in support of the Drosophila genome project (as of 10 October 2000). Further, the genes encoding 59% of these novel ESTs are not predicted by algorithms used for fly genome annotation. From our analysis of ESTs that do not correspond to one of the 13,601 annotated genes, we predict that the number of genes in the Drosophila genome may be underestimated by 10-15% (approximately 1,300 to 2,000 genes).

Results and discussion

Library quality assessment

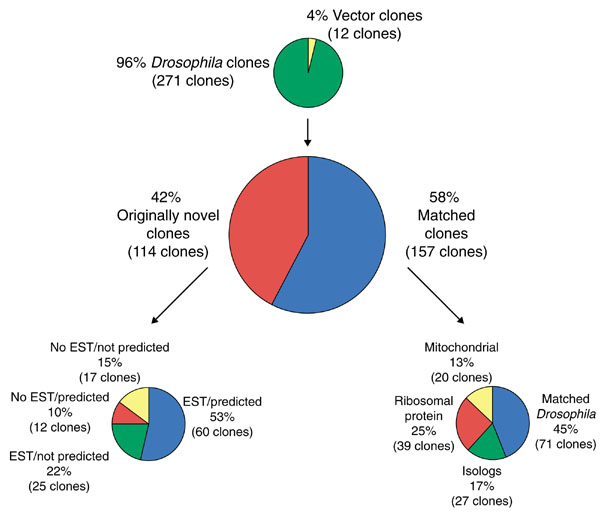

Desiccated brain tissue from adult Drosophila melanogaster was used to construct a library using the Stratagene Hybrid-Zap system. This library was designed for protein expression and, therefore, was constructed such that full-length cDNAs containing 5' untranslated regions are not likely to be present. The number of clones in the library and the size of the clones were used to assess the quality of the library. The number of clones in the primary library was determined by titering one of the five packaging reactions. The total number of clones in the primary library is 6.75 × 106 (that is, all five packaging reactions). From the analysis of the fully sequenced clones (141 novel and matched isolog clones reported in this study), the majority of the inserts (53%) were between 400 and 800 base pairs (511 base pairs ± 197 base pairs average deviation). Characterized clones from the library range between 139 to 1,746 base pairs (bp), including only 15 As of the poly(A) tail. The insert size for this library is as expected using the Stratagene Hybrid-Zap kit, given that the size-selection column retains DNA molecules larger than 200 bp) (Stratagene technical support, personal communication). Of the 283 clones that were either completely or end-tagged sequenced, approximately 4% (12 clones) did not contain an insert (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scheme for classifying the Drosophila brain library clones.

Clone selection

To try to maximize the discovery of novel transcripts, we investigated whether there was a correlation between transcript abundance and the presence of the sequence in a public database. Specifically, a reverse northern blot experiment using radiolabeled head cDNA was performed to determine whether hybridization level could be used to identify frequently occurring transcripts. We reasoned that the abundance of these transcripts may increase their representation in data banks when compared to less abundant transcripts. The data from this experiment are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Hybridization data from 85 randomly chosen clones

| Hybridization level | Originally novel | Signal |

| Absent | AF171761 | 242.2 |

| AF171771 | 282.1 | |

| AF171773 | 212.4 | |

| AF171774 | 264.8 | |

| AF171776 | 262.6 | |

| AF171777 | 293.6 | |

| AF171778 | 296.6 | |

| AF171781 | 299.4 | |

| AF171762 | 194.0 | |

| AF179229 | 211.9 | |

| Light | AF171764 | 428.0 |

| AF171765 | 461.4 | |

| AF171769 | 483.8 | |

| AF171772 | 305.0 | |

| AF171779 | 460.6 | |

| AF171782 | 335.6 | |

| AF171785 | 360.3 | |

| AF179230 | 444.6 | |

| Medium | AF171763 | 508.5 |

| AF171766 | 617.2 | |

| AF171767 | 615.6 | |

| AF171768 | 541.3 | |

| AF171770 | 509.0 | |

| AF171786 | 681.5 | |

| AF171787 | 924.1 | |

| AF171789 | 984.0 | |

| AF171790 | 978.2 | |

| AF171791 | 862.7 | |

| AF171792 | 583.2 | |

| AF171793 | 731.2 | |

| AF171794 | 695.5 | |

| Dark | AF171762 | 1237.0 |

| AF171775 | 1066.0 | |

| Hybridization level | Known | Signal |

| Absent | None | |

| Light | AF171706 Drosophila GS2 for glutamine synthase | 315.3 |

| AF171707 Drosophila ubiquitin protein gene | 388.6 | |

| AF171709 Drosophila cytochrome c oxidase | 365.3 | |

| AF171711 Drosophila calmodulin gene | 340.7 | |

| AF171715 Drosophila CCATT box-transmembrane domain | 392.1 | |

| Medium | AF083504 Drosophila Pls dso3465 (d149) dso 8544 (D187) | 645.3 |

| AF171701 Drosophila frequenin gene | 503.4 | |

| AF171702 Drosophila nicotinic acetylcholine receptor | 526.0 | |

| AF171704 Drosophila ADP/ATP Translocase | 537.1 | |

| AF171705 Drosophila tyrosine kinase gene | 544.5 | |

| AF171703 Drosophila ferritin subunit 1 (Fer1) mRNA | 552.0 | |

| AF171708 Drosophila mRNA for rab-related protein 4 | 543.2 | |

| AF171710 Drosophila cytochrome c oxidase subunit | 538.0 | |

| AF083505 Drosophila 2-g8 from P1 DS02782 (D71) | 870.4 | |

| AF171712 Drosophila gene encoding S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase | 918.0 | |

| AF171713 Drosophila TRIP-1 homolog (Dm TRIP) mRNA | 576.6 | |

| AF171714 Drosophila twinstar (tsr) gene | 664.1 | |

| AF171716 Drosophila burdock retrotransposon gag protein | 631.6 | |

| AF171717 Drosophila GS1 mRNA for glutamine synthase | 557.8 | |

| AF171718 Drosophila geranylgeranyl transferase | 694.9 | |

| Dark | None | |

| Hybridization level | Ribosomal/mitochondrial | Signal |

| Absent | AF083279 Ribosomal protein rat 60s L35A | 235.1 |

| AF083516 Drosophila ribosomal protein S17 gene | 299.2 | |

| AF083518 Drosophila ribosomal protein L31 | 218.4 | |

| Light | AF083272 Yeast ribosomal protein L46 | 489.6 |

| Clone 17 Mitochondrial 16S ribosomal mRNA | 480.4 | |

| Clone 26 Mitochondrial 16S ribosomal mRNA | 343.2 | |

| AF083276 M. musculus ribosomal protein L21 mRNA | 361.4 | |

| AF083277 M. musculus ribosomal protein L21 mRNA | 388.1 | |

| AF083278 Ribosomal protein human 60s L24 | 326.8 | |

| AF083515 Drosophila ribosomal protein 15a (40s subunit) | 376.5 | |

| Clone 61 Mitochondrial 16S ribosomal mRNA | 354.1 | |

| Clone 72 Mitochondrial 16S ribosomal mRNA | 470.5 | |

| AF083520 Drosophila ribosomal protein L18a | 352.6 | |

| AF083521 Drosophila ribosomal protein S14 A and B genes | 396.5 | |

| Medium | AF083513 Drosophila mRNA ribosomal protein | 508.8 |

| AF083514 Drosophila ribosomal protein L19 gene | 579.8 | |

| AF083281 Ribosomal protein R. norvegicus S23 | 798.1 | |

| AF083519 Drosophila 60S ribosomal protein L43 mRNA | 837.9 | |

| Clone 80 Mitochondrial 16S ribosomal mRNA | 601.1 | |

| Clone 90 Mitochondrial 16S ribosomal mRNA | 798.6 | |

| AF083522 Drosophila 5.8S and 2S ribosomal rRNA | 819.8 | |

| Clone 94 Mitochondrial 16S ribosomal mRNA | 820.0 | |

| Dark | AF083275 Drosophila ribosomal protein S18 mRNA | 1166.0 |

| AF083517 Drosophila ribosomal protein L22 mRNA | 2423.0 | |

| Hybridization level | Isologs | Known |

| Absent | AF083295 C. pothophila cytochrome oxidase I & II | 224.9 |

| AF083300 Human clathrin coat-associated protein 50 | 233.7 | |

| Light | AF083301 R. norvegicus trg mRNA carrier protein precursor | 474.5 |

| Medium | AF083296 Human protein synthesis factor (eIF-1A) | 512.2 |

| AF083298 Silkworm mRNA for DNA SC factor | 500.1 | |

| AF083297 Bovine ATP synthase G chain, mitochondrial, H+ transporting | 555.9 | |

| AF083299 H. sapiens Arp 2/3 complex 20 kD subunit, actin related protein | 570.4 | |

| AF083302 H. sapiens mRNA for testican | 519.7 | |

| Dark | None | |

The photo stimulating units (psl) within a circle of standard area was used to determine the relative hybridization level to radiolabeled head cDNA for each clone. Hybridization categories are as follows. Absent, 0-300 psl (corresponding to background); light, 301-499 psl; medium, 500-899 psl; dark, 900-2500 psl. Clones are categorized as follows. Novel, sequence information for clones that were novel at the initial phase of this project; known, Drosophila sequence information previously submitted to sequence databanks; ribosomal protein/ribosomal RNA/mitochondrial, sequences corresponding to ribosomal proteins, ribosomal RNAs or mitochondrial transcripts; isologs, transcripts that have a high degree of similarity to sequences reported in the databanks.

The level of hybridization to the probe varied considerably within a category. In particular, novel transcripts did not uniformly have low levels of hybridization, which suggested that hybridization level would not greatly aid in identifying novel clones. Therefore, subsequent clones for this study were randomly chosen for sequence analysis. It is possible that abundant transcripts may not be as well represented in the database as a result of directed cloning of rarer molecules, or that cDNA abundance in this library may not accurately reflect relative transcript abundance in the fly brain.

Sequence data

We obtained sequence data for 271 independently isolated cDNAs representing transcripts expressed in the Drosophila brain (Figure 1, Table 2). Of these, 141 clones originally classified as either novel (114 clones) or matched isologs (27 clones) were completely sequenced. Only end-tag sequence data was collected for clones classified as matched isolog ribosomal protein sequences (16 clones), known Drosophila sequences (71 clones) and known Drosophila ribosomal protein sequences (23 clones). All insert sequences or ESTs can be obtained by searching GenBank with the appropriate accession numbers listed in Table 2. Data for 20 mitochondrial 16S clones are not reported here because mitochondrial expression is not the focus of this study.

Table 2.

GenBank accession numbers of all sequenced clones

Sequences classified as 'novel' represent new EST sequence data from D.melanogaster (as of 10 October, 2000)and are not homologous to any EST or cDNA sequence in GenBank. These 17 novel sequences are not predicted to be transcribed, and are described in more detail in Table 5b. Sequences classified as 'matched with an EST' correspond to known EST sequence data, but do not have a corresponding predicted gene. Sequences classified as 'matched with a predicted gene' correspond to those that are predicted genes, but do not have corresponding EST data. Sequences classified as 'matched with an EST and a predicted gene' have both EST and predicted gene matches. Sequences classified as 'matched isologs' are sequences that are homologous to genes found in other organisms. Sequences classified as 'matched isolog ribosomal protein' are sequences that are homologous to ribosomal protein genes found in other organisms. Sequences classified as 'known Drosophila ribosomal protein sequences' are matched with sequences previously reported to GenBank. Sequences classified as 'known Drosophila' are sequences that have been previously reported to databases (AF083507 and AF083508 correspond to clone 159; AF083509 and AF083510 correspond to clone 226).

We generated sequence data for 27 Drosophila genes that had been previously sequenced from other organisms. Isologs that were identified in the brain library but which had not been identified or sequenced in Drosophila melanogaster are listed in Table 3 (with the exception of ribosomal protein genes). An isolog is defined as a sequence that has a high degree of similarity to genes identified in other organisms, but the functional relationship between these genes has not been demonstrated [34]. As expected, we recovered many previously identified Drosophila genes (Table 4). We did not continue with full insert sequencing of these Drosophila sequences, but the EST data for these clones was submitted to GenBank.

Table 3.

Isologs identified in Drosophila brain study

| Gene | Organism | Accession Number | Score | Probability |

| Cytochrome oxidase I and II | C. pothophila | AF083295 | 201 | 6.2e-8 |

| Protein synthesis factor eIF-1A | H. sapiens | AF083296 | 237 | 1.1e-23 |

| ATP synthase G chain | B. taurus | AF083297 | 282 | 2.6e-30 |

| DNA supercoiling factor | Silkworm | AF083298 | 249 | 1e-65 |

| Arp2/3 complex 20 kD subunit | H. sapiens | AF083299 | 681 | 3.7e-85 |

| Clathrin coat-associated protein 50 | H. sapiens | AF083300 | 663 | 1.5e-85 |

| Trg gene | R. norvegicus | AF083301 | 300 | 7.1e-39 |

| Testican gene | H. sapiens | AF083302 | 806 | 8.8e-57 |

| Calmodulin-like processed pseudogene (similar to D. melanogaster DMTnc 73F troponin but not identical) | H. sapiens | AF083303 | 123 | 1.0e-27 |

| Peripheral type benzadiazipine receptor | H. sapiens | AF083304 | 220 | 5.3e-38 |

| Retinal protein 4 | H. sapiens | AF083305 | 459 | 4.2e-73 |

| Ubiquitin-like S30 ribosomal fusion protein | H. sapiens | AF083306 | 151 | 1.9e-15 |

| Insulinoma rig-analog DNA-binding protein | H. sapiens | AF083307 | 498 | 1.3e-31 |

| Neuronal calcium binding protein | C. elegans | AF083308 | 629 | 8.2e-78 |

| Mitochondrial ubiquinone-binding protein | H. sapiens | AF083309 | 115 | 2.0e-25 |

| Oxidoreductase gene | H. sapiens | AF083310 | 172 | 3.4e-23 |

| Iron-sulfur protein | R. rieske | AF083311 | 812 | 5.1e-57 |

| Copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase | H. sapiens | AF083312 | 359 | 2.0e-42 |

| Putative fatty-acid binding protein | A. gambiae | AF083313 | 530 | 1.0e-53 |

| SMT3 protein | H. sapiens | AF083314 | 649 | 8.3e-44 |

| Core P2 precursor ubiquinol cytochrome c reductase complex | B. taurus | AF083315 | 172 | 5.5e-15 |

| Tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase | H. sapiens | AF083316 | 500 | 7.8e-39 |

| Transferrin gene | Flesh fly | AF083317 | 511 | 1.0e-61 |

| Leucyl-tRNA synthetase | A. thaliana | AF083318 | 179 | 3.1e-72 |

| Protein translation factor SUI1 | A. gambiae | AF083319 | 381 | 1.8e-47 |

| Uracil phosphoribosyl transferase | S. cerevisiae | AF083320 | 434 | 8.7e-51 |

| Metallopanstimulin gene | H. sapiens | AF083321 | 322 | 3.3e-39 |

'Gene' indicates the homologous gene name, 'organism' indicates the organism which has the greatest similarity to the Drosophila clone, and the accession number for the Drosophila isolog is listed. The 'score' and 'probability' for each match using BLASTN [41] are reported.

Table 4.

Brain cDNA clones matched with previously reported Drosophila genes

| Gene | Accession number | Location | Reference |

| Frequenin gene | AF171701 | CNS and PNS of adults and embryos | [45] |

| Ferritin subunit 1 gene | AF171703 | Fat body and gut of larvae, present in all stages and increased with iron supplementation | [46] |

| Tyrosine kinase gene | AF171705 | Not specified | - |

| Glutamine synthase gene | AF171706 | Mitochondrial | |

| AF171717 | |||

| Rab-related protein 4 gene | AF171708 | Endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi (rats expression highest in brain) | [47,48] |

| S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase gene | AF171712 | Polyamine synthesis, presumably in every cell, highest in 24 and 48 h larvae | [49] |

| Twinstar gene | AF171714 | Male germ line and larvae throughout development | [50,51] |

| CCATT box transmembrane domain gene | AF171715 | Not specified | - |

| Geranylgeranyl transferase gene | AF171718 | Not specified | - |

| ADP-robosylation factor class II gene | AF171722 | Uniformly distributed ubiquitous in all adult body segments | [52,53] |

| Virus-like particle | AF171727 | Long gland and ovipositor in adults | [54] |

| Rot gene | AF171731 | Not specified | - |

| DNA-binding protein erect wing | AF171732 | Throughout embryonic development and enriched in adult head | [55] |

| Membrane-associated protein gene | AF171736 | Uniform in embryonic development | [56] |

| BBC-1 gene | AF171739 | Not specified | - |

| Vimar gene | AF171743 | Midgut and hindgut, visceral mesoderm, CNS, and PNS in embryos | [57] |

| Metallothionein gene | AF171741 | Alimentary canal and lower in other tissues of larvae | [58] |

| Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor gene | AF171702 | Brain and CNS predominantly in late embryos and adult head | [59,60,61] |

| Burdock retrotransposon gag protein gene | AF171716 | Not specified | - |

| Transposable element to copia mgd3 retroposon | AF171724 | Varies with Drosophila populations | [62,63] |

| AF171725 | |||

| Heat-shock gene hsp 27 | AF171728 | CNS, sperm, and oocytes, present in all stages, highest in white prepupae | [64,65] |

| Alpha 1,2 mannosidase gene | AF171730 | Embryonic PNS, adult eye, and wing | [66] |

| GTP cyclohydrolase I | AF171733 | Embryo nuclear, adult eye and head | [67,68] |

| Teashirt gene | AF171735 | Epidermis and mesoderm during development | [69] |

| AF171759 | |||

| 49 kD phosphoprotein | AF171737 | Photoreceptors | [70] |

| AF171738 | |||

| Alcohol dehydrogenase related gene | AF171740 | Not specified | - |

| Vacuolar-ATPase gene | AF171742 | Uniform expression in all stages | [71] |

| Micropia-Dm11 3' flanking DNA | AF171746 | Not specified | - |

| AF171748 | |||

| RM62 RNA helicase | AF171749 | Not specified | - |

| ADP/ATP translocase | AF171704 | Not specified | - |

| Ubiquitin protein gene | AF171707 | Tissue-general, all life stages | [72] |

| Calmodulin gene | AF171711 | CNS and mushroom bodies of adults | [73] |

| AF171781 | |||

| TRIP-1 homolog gene | AF171713 | Not specified | - |

| AF171726 | |||

| Bnb gene for development | AF171729 | Mesectoderm and presumptive epidermis, after dorsal closure periphery of nervous system including glia that may establish longitudinal neuropile scaffolding, embryonic CNS | [74] |

| AF171751 | |||

| B(2)gcn gene | AF171754 | Not specified | - |

| Diacylglycerol kinase gene | AF171720 | Eye-specific in adult nervous system, muscles, compound eye, | [75,76] |

| AF171721 | brain cortex, fibrillar muscle, and tubular muscle | ||

| AF171755 | |||

| AF171756 | |||

| Gene from heat-shock locus 93D | AF171760 | Constitutive monitoring the 'health' of translation machinery, presumably in every cell | [77,78] |

| Cytochrome c oxidase gene | AF171709 | Mitochondrial | |

| AF171710 | |||

| AF171719 | |||

| AF171723 | |||

| AF171734 | |||

| AF171752 | |||

| BM40 gene | AF171872 | Not specified | - |

| Histone H3.3 gene | AF171745 | Gonads and somatic tissue, uniform distribution in polytene chromosomes | [79,80] |

| Acetylcholine receptor-related protein | AF171747 | CNS | [81] |

| Hu-li tai shao gene | AF171750 | Ovarian ring canal | [82] |

| Laminin receptor gene | AF171753 | Neural tissue | [83] |

| eIF-2 alpha-subunit | AF171758 | Expressed throughout embryos, and CNS in later stages | [84,85] |

| Gerceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase-2 gene | AF171757 | Evenly distributed, expressed in all stages | [86] |

| CNS-specific Noe gene | AF171772 | CNS | [87] |

| AF171796 | |||

| AF171818 | |||

| AF171848 | |||

| AF171780 | |||

| Medea-B gene | AF171807 | Not specified | - |

| Phospholipase C norpA gene | AF171840 | Retina and body of adults | [88] |

| Recq helicase 5 gene | AF171784 | DNA repair, recombination, and replication | [89] |

Each previously identified gene is listed with its accession number from the Drosophila brain study. Location information is as reported by the indicated reference.

Approximately 42% of the sequence data generated in this study were originally novel according to sequence analysis searches conducted at the beginning of this project. Since then, much EST data has been added to GenBank and the Drosophila genome sequence has been released. Thus, in October 2000 the 114 previously novel brain cDNA were again compared with fly sequence data. The percentage of transcripts that do not have corresponding ESTs is reduced to 11% (Table 2; of 29 clones, 17 have no EST matches and are not predicted genes following genome annotation, and 12 have no EST matches but are matched with a predicted gene). Although each of these 29 clones lacks an EST match, each clone is identified within the Drosophila genome sequence recently reported by Adams et al. [35]. It is possible that some of these clones represent the 3' ends of ESTs for which only 5' sequence data is available. Considering that data for approximately 80,000 ESTs (24,193 ESTs from adult heads alone) are reported [36] and that our analysis examined only 271 randomly chosen brain library clones, 11% is a surprisingly large number. This indicates that this library is a valuable resource for generating sequence data that will facilitate genome annotation, specifically identifying regions transcribed in the adult fly brain.

From our analysis it is clear that EST data are essential for accurate and thorough genome annotation. In particular, using current genome annotation algorithms, 42 of the 271 brain clones do not correspond to predicted genes (Table 2). Of these 42 clones, however, 25 have EST matches with the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project (BDGP) data (Tables 2, 5). Comparisons of the remaining 17 cDNA sequences with the Drosophila genome sequence show evidence of RNA processing (exon/intron borders and consensus splicing sequences) for two clones, and presence of a poly(A) addition sequence (AAUAAA) 12 to 30 bp upstream of an extensive poly(A) region at the 3' end of the insert sequence for seven clones (Table 5b). Ten of the 17 clones were detected in reverse northern experiments using either brain or body radiolabeled cDNA (Table 6). The distribution of detection by brain cDNA, body cDNA, both or neither (not detectable above background) for the 17 clones in this category is similar to the distributions observed in the other categories (Tables 5a, 6), and strikingly similar to the detection frequency observed for the 'matched with an EST and a predicted gene' category. Although these data suggest that these sequences are transcribed, additional experiments are necessary to confirm whether this is true for each clone. None of the clones in this category is predicted to encode a protein larger than 100 amino acids. It is possible that these sequences may correspond to genomic DNA. Alternatively, these novel RNA molecules may perform some unknown cellular function that requires a conserved structure rather than a conserved sequence.

Table 5a.

Correlation between EST match, gene prediction and hybridization analysis

| Detected in | Accession number | Insert size | Percentage of category | |||

| Novel cDNA | ||||||

| Body | AF171819 | 145 | 12% | |||

| Body | AF171858 | 186 | ||||

| Both | AF171764 | 450 | 12% | |||

| Both | AF171805 | 259 | ||||

| Brain | AF171789 | 857 | 35% | |||

| Brain | AF171794 | 610 | ||||

| Brain | AF171800 | 190 | ||||

| Brain | AF171808 | 269 | ||||

| Brain | AF171815 | 363 | ||||

| Brain | AF171854 | 195 | ||||

| Neither | AF171813 | 216 | 41% | |||

| Neither | AF171821 | 359 | ||||

| Neither | AF171828 | 189 | ||||

| Neither | AF171838 | 430 | ||||

| Neither | AF171850 | 1104 | ||||

| Neither | AF171859 | 1786 | ||||

| Neither | AF171865 | 452 | ||||

| Matched with an EST, but NOT a predicted gene | ||||||

| Body | AF171857 | 432 | 4% | |||

| Both | AF171772 | 480 | 32% | |||

| Both | AF171779 | 1101 | ||||

| Both | AF171787 | 449 | ||||

| Both | AF171804 | 553 | ||||

| Both | AF171818 | 180 | ||||

| Both | AF171839 | 1282 | ||||

| Both | AF171848 | 345 | ||||

| Both | AF171860 | 151 | ||||

| Brain | AF171766 | 798 | 36% | |||

| Brain | AF171780 | 292 | ||||

| Brain | AF171781 | 400 | ||||

| Brain | AF171782 | 506 | ||||

| Brain | AF171785 | 727 | ||||

| Brain | AF171796 | 313 | ||||

| Brain | AF171797 | 400 | ||||

| Brain | AF171811 | 386 | ||||

| Brain | AF171863 | 1072 | ||||

| Neither | AF171826 | 683 | 28% | |||

| Neither | AF171829 | 380 | ||||

| Neither | AF171837 | 503 | ||||

| Neither | AF171840 | 623 | ||||

| Neither | AF171845 | 376 | ||||

| Neither | AF171862 | 800 | ||||

| Neither | AF171869 | 641 | ||||

| Matched with a predicted gene, but NOT an EST | ||||||

| Body | AF171867 | 287 | 8.3% | |||

| Both | AF171768 | 1746 | 33.3% | |||

| Both | AF171778 | 389 | ||||

| Both | AF171790 | 396 | ||||

| Both | AF171799 | 819 | ||||

| Brain | AF171771 | 1060 | 33.3% | |||

| Brain | AF171783 | 373 | ||||

| Brain | AF171803 | 688 | ||||

| Brain | AF171812 | 338 | ||||

| Neither | AF171832 | 338 | 25% | |||

| Neither | AF171861 | 398 | ||||

| Neither | AF171868 | 689 | ||||

| Matched with an EST and a predicted gene | ||||||

| Body | AF171846 | 578 | 3% | |||

| Body | AF171856 | 600 | ||||

| Both | AF171763 | 236 | 30% | |||

| Both | AF171770 | 919 | ||||

| Both | AF171773 | 315 | ||||

| Both | AF171774 | 745 | ||||

| Both | AF171776 | 278 | ||||

| Both | AF171777 | 165 | ||||

| Both | AF171786 | 223 | ||||

| Both | AF171791 | 451 | ||||

| Both | AF171792 | 619 | ||||

| Both | AF171793 | 234 | ||||

| Both | AF171795 | 200 | ||||

| Both | AF171798 | 733 | ||||

| Both | AF171809 | 577 | ||||

| Both | AF171810 | 966 | ||||

| Both | AF171817 | 250 | ||||

| Both | AF171830 | 567 | ||||

| Both | AF179229 | 1396 | ||||

| Both | AF179230 | 168 | ||||

| Brain | AF171761 | 1081 | 27% | |||

| Brain | AF171762 | 652 | ||||

| Brain | AF171765 | 281 | ||||

| Brain | AF171767 | 228 | ||||

| Brain | AF171769 | 1051 | ||||

| Brain | AF171775 | 523 | ||||

| Brain | AF171788 | 1421 | ||||

| Brain | AF171801 | 600 | ||||

| Brain | AF171802 | 623 | ||||

| Brain | AF171806 | 727 | ||||

| Brain | AF171807 | 380 | ||||

| Brain | AF171814 | 237 | ||||

| Brain | AF171816 | 324 | ||||

| Brain | AF171822 | 376 | ||||

| Brain | AF171824 | 785 | ||||

| Brain | AF171833 | 868 | ||||

| Neither | AF171784 | 351 | 40% | |||

| Neither | AF171820 | 427 | ||||

| Neither | AF171823 | 234 | ||||

| Neither | AF171825 | 675 | ||||

| Neither | AF171827 | 253 | ||||

| Neither | AF171831 | 222 | ||||

| Neither | AF171834 | 240 | ||||

| Neither | AF171835 | 916 | ||||

| Neither | AF171836 | 406 | ||||

| Neither | AF171841 | 436 | ||||

| Neither | AF171842 | 331 | ||||

| Neither | AF171843 | 99 | ||||

| Neither | AF171844 | 764 | ||||

| Neither | AF171847 | 301 | ||||

| Neither | AF171849 | 193 | ||||

| Neither | AF171851 | 364 | ||||

| Neither | AF171852 | 364 | ||||

| Neither | AF171853 | 473 | ||||

| Neither | AF171855 | 991 | ||||

| Neither | AF171864 | 541 | ||||

| Neither | AF171866 | 412 | ||||

| Neither | AF171870 | 399 | ||||

| Neither | AF171871 | 488 | ||||

| Neither | AF171872 | 546 | ||||

Hybridization results for the indicated cDNA categorized as 'novel cDNA'; 'matched with an EST, but not a predicted gene'; 'matched with a predicted gene, but not an EST'; or 'matched with an EST and a predicted gene' (see Table 2). Purified plasmids containing the indicated insert sequence were hybridized with either labeled brain or body cDNA (see Table 6). The percentage of clones exhibiting the indicated hybridization pattern within each category is indicated.

Table 5b.

Additional information

| Accession number | EST hit? | Predicted gene? | AAATAA/Poly(A) spacing | Splicing detected? | Expression detected in | Insert size | Comments |

| AF171819 | NO | NO | 37 | Body | 145 | ||

| AF171858 | NO | NO | 18 | Body | 186 | ||

| AF171764 | NO | NO | 280 | Both | 450 | ||

| AF171805 | NO | NO | 25 | Both | 259 | ||

| AF171789 | NO | NO | 134 | Brain | 857 | ||

| AF171794 | NO | NO | 45 | Brain | 610 | ||

| AF171800 | NO | NO | Not present | Brain | 190 | ||

| AF171808 | NO | NO | 23 | Brain | 269 | ||

| AF171815 | NO | NO | 12 | Brain | 363 | ||

| AF171854 | NO | NO | 52 | Spliced, consensus | Brain | 195 | Extensive poly(A) tail (146 nucleotides) |

| AF171813 | NO | NO | Not present | Neither | 216 | Extensive poly(A) tail (>42 nucleotides) | |

| AF171821 | NO | NO | Not present | Spliced, consensus | Neither | 359 | |

| AF171828 | NO | NO | Not present | Neither | 189 | ||

| AF171838 | NO | NO | 18 | Neither | 430 | ||

| AF171850 | NO | NO | 13 | Neither | 1104 | ||

| AF171859 | NO | NO | 18 | Neither | 1786 | ||

| AF171865 | NO | NO | Not present | Neither | 452 |

Additional information concerning clones that lack EST data and that are not predicted to be transcribed (Novel cDNA). The GenBank accession number for each of the 17 clones is indicated. The distance between a putative poly(A) addition sequence (AAATAAA), when present, and the poly(A) sequence is shown. 'Splicing detected?' indicates the two cDNA clones showing evidence for consensus splicing. 'Expression detected' refers to each clone's hybridization results when probed with radiolabeled cDNA from brain or body (see Table 6). 'Insert size', size of the cDNA insert; 'comments', additional comments for the identified clone. None of the 17 cDNA is predicted to encode a protein larger than 100 amino acids.

Table 6.

Body versus brain expression of originally novel clones

| Clone category | GenBank accession number | psl/mm2-bkg | Total | |

| Brain | Body | |||

| Brain only | AF171761 | 1.52 | ND | 34 |

| AF171765 | 0.68 | ND | ||

| AF171766 | 0.60 | ND | ||

| AF171767 | 1.62 | ND | ||

| AF171769 | 0.15 | ND | ||

| AF171771 | 0.79 | ND | ||

| AF171775 | 1.20 | ND | ||

| AF171780 | 4.18 | ND | ||

| AF171781 | 1.10 | ND | ||

| AF171782 | 1.03 | ND | ||

| AF171783 | 0.94 | ND | ||

| AF171785 | 1.52 | ND | ||

| AF171788 | 1.44 | ND | ||

| AF171789 | 0.77 | ND | ||

| AF171794 | 0.61 | ND | ||

| AF171796 | 3.74 | ND | ||

| AF171797 | 0.87 | ND | ||

| AF171800 | 1.01 | ND | ||

| AF171801 | 0.98 | ND | ||

| AF171802 | 0.46 | ND | ||

| AF171803 | 0.86 | ND | ||

| AF171806 | 1.15 | ND | ||

| AF171807 | 0.70 | ND | ||

| AF171808 | 0.92 | ND | ||

| AF171811 | 0.38 | ND | ||

| AF171812 | 0.60 | ND | ||

| AF171814 | 0.90 | ND | ||

| AF171815 | 0.91 | ND | ||

| AF171816 | 0.24 | ND | ||

| AF171822 | 5.43 | ND | ||

| AF171824 | 1.14 | ND | ||

| AF171833 | 0.34 | ND | ||

| AF171854 | 0.20 | ND | ||

| AF171863 | 3.73 | ND | ||

| Body and brain | AF171762 | 3.94 | 0.01 | 33 |

| AF171763 | 2.81 | 8.92 | ||

| AF171764 | 1.13 | 0.06 | ||

| AF171768 | 1.76 | 0.39 | ||

| AF171770 | 1.25 | 0.70 | ||

| AF171772 | 14.1 | 0.81 | ||

| AF171773 | 1.03 | 0.43 | ||

| AF171774 | 0.77 | 0.04 | ||

| AF171776 | 1.09 | 0.43 | ||

| AF171777 | 1.20 | 1.65 | ||

| AF171778 | 1.45 | 2.48 | ||

| AF171779 | 0.67 | 0.55 | ||

| AF179229 | 2.46 | 0.09 | ||

| AF179230 | 1.38 | 3.88 | ||

| AF171786 | 0.77 | 0.03 | ||

| AF171787 | 1.14 | 1.02 | ||

| AF171790 | 1.17 | 0.80 | ||

| AF171791 | 1.07 | 6.13 | ||

| AF171792 | 1.25 | 1.56 | ||

| AF171793 | 1.19 | 1.47 | ||

| AF171795 | 3.32 | 0.68 | ||

| AF171798 | 0.92 | 0.31 | ||

| AF171799 | 1.30 | 0.05 | ||

| AF171804 | 1.05 | 0.47 | ||

| AF171805 | 1.11 | 0.13 | ||

| AF171809 | 2.22 | 0.49 | ||

| AF171810 | 1.34 | 0.12 | ||

| AF171817 | 0.63 | 0.01 | ||

| AF171818 | 18.3 | 0.94 | ||

| AF171830 | 0.31 | 0.01 | ||

| AF171839 | 9.93 | 2.40 | ||

| AF171848 | 20.7 | 0.13 | ||

| AF171860 | 23.4 | 0.67 | ||

| Body only | AF171819 | ND | 12.9 | 6 |

| AF171846 | ND | 0.08 | ||

| AF171856 | ND | 0.06 | ||

| AF171857 | ND | 0.19 | ||

| AF171858 | ND | 0.35 | ||

| AF171867 | ND | 0.21 | ||

| Neither body nor brain | AF171784 | ND | ND | 41 |

| AF171813 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171820 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171821 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171823 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171825 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171826 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171827 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171828 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171829 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171831 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171832 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171834 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171835 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171836 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171837 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171838 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171840 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171841 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171842 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171843 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171844 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171845 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171847 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171849 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171850 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171851 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171852 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171853 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171855 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171859 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171861 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171862 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171864 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171865 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171866 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171868 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171869 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171870 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171871 | ND | ND | ||

| AF171872 | ND | ND | ||

Purified plasmid DNA was spotted onto a nylon filter and hybridized with either radiolabeled brain or body cDNA. Clones are classified on the basis of whether they were detected with brain, body, both (brain and body) or neither (not above background) radiolabeled cDNA. The clones tested were originally novel (no EST or previous sequence information), but some clones have changed classification as a result of both the large number of ESTs submitted thorough the Drosophila genome effort (BDGP) and the Drosophila genome annotation efforts. Additional information for these clones is listed in Tables 2, 5. ND, not determined. Bkg, background.

The Drosophila genome is predicted to contain 13,601 genes [35]. Ifour observations are representative and can be extended to the number of genes in the fly genome, then our analysis suggests that the total number of genes may be underestimated by approximately 15% (42 of the 271 randomly chosen cDNAs do not correspond to a predicted gene). Thus, approximately 2,000 genes may await discovery.

Transcript distribution analysis

A second hybridization study was conducted to determine whether clones originally identified as novel were detectable in the brain and/or body of adult Drosophila. This data may offer clues as to which transcripts are involved in basic neuronal function, as opposed to a function that may be specific to the brain. The Drosophila central nervous system (CNS) includes thoracic and abdominal ganglia and, therefore, neural transcripts are often expressed throughout the body. Thus, it was possible that few transcripts would be brain-specific.

To determine how the (originally) novel clones were distributed in the animal, plasmid templates from 114 novel clones were spotted on filters and hybridized with radiolabeled cDNA from either brains or bodies (minus heads). The results of this study are listed in Table 6. In this experiment cDNA probe is limiting and, therefore, many transcripts that are in low abundance may not be detectable. In fact, 36% of the clones were not detected in either brain or body. These clones may correspond to less abundant transcripts. Ideally, hybridization probe would be in excess in these experiments to determine which clones are brain specific, but Drosophila brain cDNA is limiting. Approximately 30% of the clones were detectable only in the brain and are candidates for genes involved in brain function. Clones that were detected in both tissues made up about one third of the novel transcripts (29%). About 5% of the clones were detected only in the body. As the library is made from brain tissue, we did not expect to recover many transcripts that would only be detectable in the body, as compared to the brain.

We used published localization data from previously identified transcripts to evaluate the data we collected for the novel clones (Table 4). Approximately 22% (7 of 32) of the known Drosophila genes listed are neural-specific, and approximately 30% of novel transcripts were detected only in the brain. Approximately 29% of the novel transcripts were detectable in both brain and body tissues. Known Drosophila genes that were localized in body and brain tissues accounted for 56% (18 of 32) of genes for which localization data was available (Table 4). Clones detected in both tissues may indicate that the gene product is needed in all cells. Genes from the nervous system would be expected to be expressed in both tissues, so transcripts detected in both cannot be ruled out of this category; but these transcripts are not brain specific. Approximately 5% of the novel clones were detectable only in the body, as compared to 22% (7 of 32) of the known Drosophila clones detected only in body tissues. These transcripts are apparently expressed at a higher level in the body and at relatively low levels in the brain. It should be noted that localization data were not specified for 18 of the 49 (37%) known transcripts listed in Table 4. This analysis suggests that this brain cDNA library is a rich source for generating cDNA sequence information and for identifying novel, brain-specific cDNAs.

Conclusions

The initial analysis of an adult Drosophila brain library is presented here. Somewhat surprisingly, we observe no clear connection between the abundance of a transcript and its appearance in a sequence data bank. However, molecular screens that are directed towards isolating rare transcripts may skew the transcript-related data in sequence banks towards less abundant molecules. As shown in Figure 1 and Table 2, we have identified and sequenced 29 novel clones that do not match with other known expressed sequences (but do match with fly genomic sequence information), 85 clones that are matched with EST data, 71 clones that were previously reported Drosophila sequences, 39 clones that contain ribosomal protein sequences, 27 clones that are matched with genes previously reported for other organisms (isologs, Table 3) and 20 clones corresponding to mitochondrial sequences.

Why did we recover such a high percentage of novel sequences? Libraries made from brain tissue are proposed to have a higher complexity of transcripts than libraries made from other tissues [21]. Therefore, EST screens of brain libraries should yield larger numbers of independent transcripts, as a result of the increased transcript complexity within brain tissues. Another possible explanation for the surprisingly large number of novel cDNAs identified in our analysis is that our library is not normalized. It has been proposed that hybrids form between poly(dA) and poly(dT) sequences during the hybridization/subtraction reaction and that these sequences are subsequently lost [36].

An ultimate goal of this project is to create a database of all the transcripts expressed in the Drosophila brain and to correlate this information with their patterns of expression in the brain. This type of a database would be a valuable resource and could be used in comparative studies with other organisms. Comparisons of transcripts from organisms with relatively simple brains (Drosophila) to organisms with more complex neural function (humans) may offer insights into basic brain function and aid in the identification of transcripts involved in higher-order brain functions. The 35 clones that appear enriched in the brain may identify proteins or RNAs that are involved in a brain-specific function. Transcripts identified in this library can be directly tested for protein-protein interaction using the yeast two-hybrid capability of the library, making it a good resource for many areas of study.

Our analysis of this unique brain library demonstrates that many transcribed regions of the Drosophila genome remain undiscovered, and that approximately 2,000 more genes may be identified. Genome annotation efforts emphasize identifying protein-coding regions [37]. Thus, it is possible that some of the ESTs lacking a corresponding predicted gene were missed during genome annotation because an open reading frame (or one of sufficient size) was not predicted.

Complete genomic sequences are excellent resources, and extensive annotation of a genome makes the sequence information even more powerful. Current software is not sufficient to identify all transcribed regions within the genome. As of the year 2000, EST data for 24,193 clones from adult Drosophila head libraries is reported and estimated to represent over 40% of all Drosophila genes [38]. Our results confirm that not all transcribed regions of the genome are identified and that EST analyses are essential for accurate and complete genome annotation.

Materials and methods

Tissue preparation

To produce the animals for the brain dissections, adult Drosophila were entrained using 12 h light and 12 h darkness in temperature-controlled incubators at 25°C. Entrained adult D. melanogaster (Canton S) flies were collected 3 h after the lights were turned off, frozen on dry ice, shaken to detach heads from bodies, and separated through a screen to isolate the heads. Frozen heads were incubated in prechilled -20°C, 100% acetone (EM Science) at -20°C overnight to replace the water in the tissue with acetone [39]. Prechilling the acetone prevents the heads from thawing when added to the acetone. Heads were dried at room temperature, and brains were removed using fine dissecting tweezers.

RNA preparation

RNA was isolated according to the Micro RNA Isolation protocol from Stratagene, with the exception of homogenization. Dried tissue was homogenized in denaturing solution with β-mercaptoethanol for 1 min, incubated on ice for 15 min, and then homogenized for an additional 5 min. The addition of a rehydration step increased the yield of RNA from dried tissue to approximately the same level as fresh tissue (16-21.9 μg total RNA extracted from 100 fresh heads, 15-29.3 μg total RNA extracted from 100 acetone-dried heads with rehydration step, compared to 3-6.6 μg total RNA extracted from 100 acetone-dried heads with no rehydration step). Poly(A) RNA was isolated using the Poly(A) Quick mRNA Isolation Kit from Stratagene according to the manufacturer's instructions. Approximately 5 μg poly(A) RNA was extracted from approximately 15,000 brains. Weighing acetone-dried brains allowed us to estimate how many were used to construct the library (50 acetone-dried brains weigh 0.25 mg and 50 acetone-dried heads weigh 1.8 mg).

Library construction

The library was constructed using a Stratagene HybriZAP™ Library kit. First-strand cDNA synthesis was primed from the 3' end of the poly(A) RNA using a poly(T) primer that also contained an XhoI restriction site and a GAGA sequence (5'-GAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAACTAGTCTCGAGTTTTTTITTTTTTTTTTT-3'). 5-methyl dCTP was used during first-strand cDNA synthesis to protect internal XhoI sites. Second-strand synthesis was primed by the partially digested RNA that resulted from RNase H treatment of the first-strand synthesis reaction. Pfu DNA polymerase was used to blunt the cDNA and EcoRI adapters were ligated to the blunt ends. The cDNA was digested with EcoRI and XhoI, size separated (retaining molecules approximately 200 bp or larger), ligated into HybriZAP™ vector arms, and packaged into phage heads for amplification.

Determining the number of primary clones

The cDNA library was titered to determine how many independent clones were recovered. At the 10-1 dilution there were 270 plaques per plate, giving a total of 6.75 × 106 clones in the primary library. This number was calculated as follows: (number of plaques 270) × (dilution factor 10) × (total packaging volume 500 μl) / (total number of mg packaged 8.75 × 10-5) × (number of μl packaged 1) = 1.542 × 1010 plaque-forming units (PFU) per mg or 1.35 × 106 PFU per packaging reaction. There are five packaging reactions for the entire library for a total of 6.75 × 106 clones in the primary library.

Sequencing-template preparation

PCR template

Individual phage plaques were incubated in 400 μl SM buffer overnight and used as amplification template. Amplification reactions were performed in a total volume of 40 μl and contained 2 μl eluted phage, 40 ng of each primer (FADI 5'-CACTACAATGGATGATG-3' and RADI 5'-CTTGCGGGGTTTTTCAG-3'), 0.001% Tween 20 (Sigma), 2.5 U Taq DNA polymerase (Promega), 1x Taq polymerase buffer (Promega), 1.56 mM MgCl2 (Promega), and 0.25 mM of each dNTP (USB). PCR was performed on a Perkin-Elmer 9600 GeneAmp PCR system, as specified in the HybriZAP™ Two-Hybrid cDNA Gigapack Cloning Kit instruction manual (Stratagene). After amplification, reactions were incubated at 37°C for 15 min with 0.5 Uμl-1 exonuclease I (USB) and 0.5 Uμl-1 shrimp alkaline phosphatase (Amersham Life Sciences). Enzymes were inactivated by heat treatment at 85°C for 15 min. Resulting samples were electrophoretically separated on a 1% Agarose (Kodak) gel and compared to a quantitative marker, BioMarker-EXT (BioVentures), to estimate the DNA concentration of each sample. This DNA was directly used in subsequent sequencing reactions.

Plasmid template

Individual phage plaques were incubated in 400 μl SM buffer overnight and then used for excision. Library phage were incubated with ExAssist Helper Phage™ (Stratagene) and XL1-Blue Escherichia coli cells, and grown overnight in Luria Broth. E. coli cells were killed by heat treatment (70°C, 20 min). XLOR E. coli cells were inoculated with the released phagemids and this mixture was plated on 50μg ml-1 ampicillin (Sigma) selection medium. Resulting colonies were cultured for subsequent plasmid DNA preparation (Perfect Prep Plasmid DNA kit, 5'-3' Inc.).

Sequencing

Initial sequence information was obtained using standard sequencing methods (described below) and a vector primer directed toward the 5' end of the insert (FADI 5'-CACTACAATGGATGATG). These ESTs were evaluated using the BLAST search program [40,41] linked to the nonredundant GenBank database. Novel cDNAs and isologs were completely sequenced. If a cDNA had been previously identified, sequence determination was not continued. The second standard sequencing reaction was primed from poly(A) tail using 1.6 pmol of a poly(T) primer anchored (PLYT 5'-TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTV-3' (V=A, C, or G)). cDNA sequences were completed using an octamer-primer walking strategy [42,43].

Automated sequencing reactions were performed using ABI PRISM Dye Terminator (or dRhodomine for PLYT reactions) Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kits with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase, FS, according to the manufacturer's directions or as described for octamer-primed sequencing reactions [42,43]. The FADI primer was annealed at 48°C and the PLYT primer was annealed at 20°C. Sequencing reactions were ethanol precipitated, pellets were resuspended in 3.5 μl loading buffer, 1.5 μl was loaded onto a sequencing gel, and the data was collected by an ABI PRISM 377 DNA sequencer. Data collected from the ABI PRISM 377 DNA sequencer was manually edited using Sequencher 3.0 (GeneCodes).

Hybridization analyses

Eighty-five individual phage plaques were incubated in 400 μl SM buffer overnight and 2 μl phage eluant was used to produce a grid of plaques on a lawn of E. coli cells. Filter lifts were taken from the grid of plaques and hybridized at 65°C overnight with labeled Drosophila head cDNA at 1 × 106 cpm per ml hybridization buffer (50% formamide, 5x SSC, 0.1% Ficoll w/v, 0.1% PVP w/v, 0.1% BSA w/v, 0.1% SDS w/v, 0.2 μg ml-1 salmon sperm DNA and 1 mM EDTA). Filters were then washed sequentially at 42°C in 5x SSC for 1 h, at 65°C in 1x SSC for 1 h, and at 65°C in 0.1x SSC for 1 h. Filter lifts were exposed to phosphorimaging plates for 24 h (Fuji Medical Systems) and psl (photo stimulating units) of a standard area were determined using a Fuji Bas1000 Imager.

Hybridization of all novel clones

Plasmid DNA (10 ng) from each novel clone was denatured at 95°C for 5 min and spotted onto a nylon filter. Filters were hybridized at 65°C overnight with either labeled Drosophila body (minus head) or labeled Drosophila brain cDNA at 1 × 106 cpm ml-1 in Church and Gilbert buffer (7% SDS, 1 mM EDTA, 500 mM Na2HPO4, and pH to 7.2 with H3PO4 [44]). Filters were washed twice for 1 h (each) at 65°C in Church and Gilbert buffer. Filters were then exposed to phosphorimaging plates for 24 h, and psl of a standard area was determined using a Fuji Bas1000 Imager. 10 ng of each plasmid on the filter contains approximately 1.2 × 1012 copies and, therefore, probe is expected to be limiting in these experiments.

Categorizing clones

Clones classified as 'novel' had no obvious match to nucleic acid/protein sequence information in GenBank (a score less than 100). Novel clones may contain blocks of less than 100 bases that are matched with other sequences, but these small regions have no known functional correlation and the similarity between the two sequences was very low. It is possible that some of our novel clones could be part of an EST from the BDGP that has not been fully sequenced. Sequences categorized as matched to EST data have a high degree of similarity (a score over 100) to reported sequence information, but the previously collected sequence data was not associated with a known function. Sequences categorized as 'known Drosophila' were a perfect match (with perhaps the exception of a few bases, fewer than 10) with sequence information from Drosophila. 'Matched isologs' are sequences that have a high degree of similarity (score of over 100 at the protein level) to a gene found in another organism, but a functional homology between these genes has not been determined. Ribosomal protein sequences were categorized as 'known' or 'isologs' using the above criteria. Ribosomal protein and mitochondrial sequence clones were categorized separately because these types of transcripts frequently occurred in our library.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Hardin labs for thoughtful discussions throughout the course of this work. This work was supported by the NIH (grant R29-HG01151 to S.H.H.).

References

- Power ME. The brain of Drosophila melanogaster. J Morph. 1943;72:517–559. [Google Scholar]

- Meinertzhagen IA, Hanson TE. The development of the optic lobe. In The Development of Drosophila melanogaster Edited by Bate M, Martinez Arias A Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 1363–1491.

- Power ME. The antennal centers and their connections within the brain of Drosophila melanogaster. J Comp Neurol. 1946;85:485–517. doi: 10.1002/cne.900850307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajashekhar KP, Singh RN. Neuroarchitecture of the tritocerebrum of Drosophila melanogaster. J Comp Neurol. 1994;349:633–645. doi: 10.1002/cne.903490410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischbach KF, Dittrich AMP. The optic lobe of Drosophila melanogaster: golgi analysis of wild-type structure. Cell Tissue Res. 1989;258:441–475. [Google Scholar]

- Hanesch U, Fischbach K-F, Heisenberg M. Neuronal architecture of the central complex in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Tissue Res. 1989;257:343–366. [Google Scholar]

- Homberg U, Montague RA, Heldebrand JG. Anatomy of antenno-cerebral pathways in the brain of the sphinx moth Manduca sexta. Cell Tissue Res. 1988;254:255–281. doi: 10.1007/BF00225800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker RF, Lienhard MC, Borst A, Fishchback K-F. Neuronal architecture of the antennal lobe in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Tissue Res. 1990;262:9–34. doi: 10.1007/BF00327741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strausfeld NJ. Atlas of an Insect Brain. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1976.

- Carlson J. Olfaction in Drosophila: genetic and molecular analysis. Trends Neurosci. 1991;14:520–524. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90004-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisenberg M, Borst A, Wagner S, Byers D. Drosophila mushroom body mutants are deficient in olfactory learning. J Neurogenet. 1985;2:1–30. doi: 10.3109/01677068509100140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisenberg M. Genetic approach to learning and memory (mnemogenetics) in Drosophila melanogaster. In Fundamentals of Memory Formation: Neuronal Plasticity and Brain Function Edited by Rahmann G Prog Zool. 1989;37:3–45. [Google Scholar]

- Davis RL. Mushroom bodies and Drosophila learning. Neuron. 1993;11:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90266-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RL. Physiology and biochemistry of Drosophila learning mutants. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:299–317. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han P-L, Meller V, Davis RL. The Drosophila brain revisited by enhancer detection. J Neurobiol. 1996;31:88–102. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4695(199609)31:1<88::AID-NEU8>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch B, Hardin PE, Hambien-Coyle MJ, Rosbash M, Hall JC. A promoterless period gene mediates behavioral rhythmicity and cyclical per expression in a restricted subset of the Drosophila nervous system. Neuron. 1994;12:555–570. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90212-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich-Forster C, Stengl M, Homberg U. Organization of the circadian system in insects. Chronobiol Int. 1998;15:567–594. doi: 10.3109/07420529808993195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss R, Heisenberg M. A higher control center of locomotor behavior in the Drosophila brain. J Neurosci. 1993;13:1852–1861. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-05-01852.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchouche A, Vaysee G, Corbeire M. Immunocytochemical and learning studies of Drosophila melanogaster neurological mutant, no-bridge KS49, as an approach to the possible role of the central complex. J Neurogenet. 1993; 9:105–121. doi: 10.3109/01677069309083453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilins M, Wold R, Heisenberg M. The central complex of Drosophila melanogaster is involved in flight control: studies on mutants and mosaics of the gene ellipsoid body open. J Neurogenet. 1994;9:189–206. doi: 10.3109/01677069409167279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams MD, Soares MB, Kerlavage AR, Fields C, Venter JC. Rapid cDNA sequencing (expressed sequence tags) from a directionally cloned human infant brain cDNA library. Nat Genet. 1993;4:373–380. doi: 10.1038/ng0893-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara K, Okubo K. Identification of new genes by systematic analysis of cDNAs and database construction. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1993;4:672–677. doi: 10.1016/0958-1669(93)90048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman T, de Bruijn FJ, Green P, Keegstra K, Kende H, McIntosh L, Ohlrogge J, Raikhel N, Somerville S, Thomashow M, et al. Genes galore: a summary of methods for accessing results from large-scale partial sequencing of anonymous Arabidopsis cDNA clones. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:1241–1255. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.4.1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillier LD, Lennon G, Becker M, Bonaldo MF, Chiapelli B, Chissoe S, Dietrich N, DuBuque T, Favello A, Gish W, et al. Generation and analysis of 280,000 human expressed sequence tags. Genome Res. 1996;6:807–828. doi: 10.1101/gr.6.9.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafalshi JA, Hanfey M, Miao GH, Ching A, Lee JM, Dolan M, Tingey S. New experimental and computational approaches to the analysis of gene expression. Acta Biochim Pol. 1998;45:929–934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson B, Lu J, Shen Y, Wentland MA, Gibbs RA. Simultaneous shotgun sequencing of multiple cDNA clones. DNA Seq. 1997;7:63–70. doi: 10.3109/10425179709020153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W, Andersson B, Worley KC, Muzny DM, Ding Y, Liu W, Ricafrente JY, Wentland MA, Lennon G, Gibbs RA. Large-scale concatenation cDNA sequencing. Genome Res. 1997;7:353–358. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.4.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CN, Denome S, Davis RL. Molecular analysis of cDNA clones and the corresponding genomic coding sequences of the Drosophila dunce gene, the structural gene for cAMP-dependant phosphodiesterase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:9313–9317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.24.9313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin JCP, Wallach JS, Del Vecchil M, Wilder EL, Ahou H, Quinn WG, Tully T. Induction of dominant negative CREB transgene specifically blocks long-term memory in Drosophila. Cell. 1994;79:49–58. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90399-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoulakis EM, Kalderon D, Davis RL. Preferential expression in mushroom bodies of the catalytic subunit of protein kinase A and its role in learning and memory. Neuron. 1993;11:197–208. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90178-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin PE, Siwicki KK. The multiple roles of per in Drosophila circadian clock. Semin Neurosci. 1995;7:15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Myers MP, Wagner-Smith K, Wesley CS, Young MW, Sehgal A. Positional cloning and sequence analysis of Drosophila clock gene, timeless. Science. 1995;270:805–808. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5237.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendahl KG, Jone KR, Kulkarni SJ, Bagully SH, Hall JC. The dissonance mutation at the no-on-transient-A locus of D. melanogaster: genetic control of courtship song and sexual behavior by protein with putative RNA-binding motifs. J Neurosci. 1992;12:390–407. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00390.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams MD, Kerlavage AR, Fleichmann RD, Fuldner RA, Bult CJ, Lee NH, Kirkness ER, Weinstock KG, Gocayne JD, White O, et al. Initial assessment of human gene diversity and expression patterns based upon 83 million nucleotides of cDNA sequence. Nature. 1995;377:3–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams MD, Celniker SE, Holt RA, Evans CA, Gocayne JD, Amanatides PG, Scherer SE, Li PW, Hoskins RA, Galle RF, et al. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2000;287:2185–2195. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SM, Fears SC, Zhang L, Chen JJ, Rowley JD. Screening poly(dA/dT)- cDNAs for gene identification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4162–4167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese MG, Hartzell G, Harris NL, Ohler U, Abril JF, Lewis SE. Genome annotation assessment in Drosophila melanogaster. Genome Res. 2000;10:483–501. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.4.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin GM, Hong L, Brokstein P, Evans-Holm M, Frise E, Stapelton M, Harvey DA. A Drosophila complementary DNA resource. Science. 2000;287:2222–2224. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng H, Hardin PE, Rosbash M. Constitutive overexpression of the Drosophila period protein inhibits period mRNA cycling. EMBO J. 1994;13:3590–3598. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06666.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–10. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LB, Hardin SH. Octamer-primed cycle sequencing using dye-terminator chemistry. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2824–2826. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.11.2824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LB, Hardin SH. Octamer sequencing technology: optimization using fluorescent chemistry. ABRF News. 1998;9:6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Church GM, Gilbert W. Genomic sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1991–1995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pongs O, Lindemeier J, Zhu XR, Theil T, Engelkamp D, Krah-Jentgens I, Lambrecht HG, Kock KW, Schwemer J, Rivosecchi R, et al. Frequenin - a novel calcium-binding protein that modulates synaptic efficacy in the Drosophila nervous system. Neuron. 1993;11:15–28. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90267-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgieva T, Dunkov BC, Harizanova N, Ralchev K, Law JH. Iron availability dramatically alters the distribution of ferritin subunit messages in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2716–2721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh A, Tokunaga F, Kawamura S, Ozaki K. In situ inhibition of vesicle transport and protein processing in the dominant negative Rab1 mutant of Drosophila. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:2943–2953. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.23.2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada M, Nakanishi H, Satoh A, Hirano H, Obaishi H, Matsuura Y, Takai Y. Isolation and characterization of a GDP/GTP exchange protein specific for the Rab3 subfamily small G proteins. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3875–3878. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.3875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byus CV, Herbst EJ. Decarboyxlases for polyamine biosynthesis in Drosophila melanogaster larvae. Biochem J. 1976;154:31–33. doi: 10.1042/bj1540031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes SR, Cooper MT, Pype S, Stolow DT. Involvement of a tissue-specific RNA recognition motif protein in Drosophila spermatogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2708–2715. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunsalus KC, Bonaccorsi S, Williams E, Verni F, Gatti M, Goldberg ML. Mutations in twinstar, a Drosophila gene encoding a cofilin/ADF homologue, result in defects in centrosome migration and cytokinesis. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1243–1259. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.5.1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtagh JJ, Jr, Lee FJ, Deak P, Hall LM, Monaco L, Lee CM, Stevens LA, Moss J, Vaughn M. Molecular characterization of a conserved, guanine nucleotide-dependent ADP-ribosylation factor in Drosophila melanogaster. Biochemistry. 1993;32:6011–6018. doi: 10.1021/bi00074a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee FJ, Stevens LA, Hall LM, Murtagh JJ, Jr, Kao YL, Moss J, Vaughan M. Characterization of Class II and Class III ADP-ribosylation factor genes and proteins in Drosophila melanogaster. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21555–21560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupas S, Brehelin M, Frey F, Carton Y. Immune suppressive virus-like particles in Drosophila parasitoid: significance of their intraspecific morphological variations. Parasitology. 1996;113:207–212. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000081981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSimone SM, White K. The Drosophila erect wing gene, which is important for both neuronal and muscle development, that encodes a protein which is similar to the sea urchin P3A2 DNA binding protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3641–3649. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent WS, III, Goldstein ES, Allen SA. Sequence and expression of two regulated transcription units during Drosophila melanogaster development: Deb-A and Deb-B. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1049:59–68. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(90)90084-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo PC, Frasch M. Bagpipe-dependent expression of vimar, a novel Armadillo-repeats gene, in Drosophila visceral mesoderm. Mech Dev. 1998;72:65–75. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lastowski-Perry D, Otto E, Maroni G. Nucleotide sequence and expression of a Drosophila metallothionein. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:1527–1530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudai Y, Amsterdam A. Nicotinic receptors in the brain of Drosophila melanogaster demonstrated by autoradiography with [125I]alpha-bungarotoxin. Brain Res. 1977;130:551–555. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90117-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundelfinger ED, Schloss P. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors of the Drosophila central nervous system. J Protein Chem. 1989;8:335–337. doi: 10.1007/BF01674267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas P, Baumann A, Merz B, Gundelfinger ED. Structure and developmental expression of the D alpha 2 gene encoding a novel nicotinic acetylcholine receptor protein of Drosophila melanogaster. FEBS Lett. 1990;269:264–268. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81170-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matyunina LV, Jordan IK, McDonald JF. Naturally occurring variation in copia expression is due to both element (cis) and host (trans) regulatory variation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7097–7102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csink AK, McDonald JF. Copia expression is variable among natural population of Drosophila. Genetics. 1990;126:375–385. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.2.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauli D, Arrigo AP, Vazquez J, Tonka CH, Tissieres A. Expression of the small heat shock genes during Drosophila development: comparison of the accumulation of hsp23 and hsp27 mRNAs and polypeptides. Genome. 1989;31:671–676. doi: 10.1139/g89-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauli D, Tonka CH, Tissieres A, Arrigo AP. Tissue-specific expression of the heat shock protein HSP27 during Drosophila melanogaster development. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:817–828. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.3.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerscher S, Albert S, Wucherpfennig D, Heisenberg M, Schneuwly S. Molecular and genetic analysis of the Drosophila mas-1 (mannosidase-1) gene which encodes a glycoprotein processing alpha 1,2-mannosidase. Dev Biol. 1995;168:613–626. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell JM, McLean JR, Reynolds ER. Molecular and developmental genetics of the Punch locus, a pterin biosynthesis gene in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Genet. 1989;10:273–286. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020100316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean JR, Boswell R, O'Donnell J. Cloning and molecular characterization of a metabolic gene with development functions in Drosophila. I. Analysis of the head function of Punch. Genetics. 1990;126:1007–1019. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.4.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick A, Core N, Kerridge S, Scott MP. Homeotic response elements are tightly linked to tissue-specific elements in a transcriptional enhancer of the teashirt gene. Development. 1995;121:2799–27812. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.9.2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto H, Yamada T. Phosrestin I and II: arrestin homologs which undergo differential light-induced phosphorylation in the Drosophila photoreceptor in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;24:1306–1312. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)90683-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Kaiser K, Wieczorek H, Dow JA. The Drosophila melanogaster gene vha14 encoding a 14-kDa F-subunit of the vacuolar ATPase. Gene. 1996;172:239–243. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HS, Simon JA, Lis JT. Structure and expression of ubiquitin genes of Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:4727–4735. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.11.4727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachidi M, Lopes C, Takamatsu Y, Ohsako S, Benichou JC, Delabar JM. Dynamic expression pattern of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II gene in the central nervous system of Drosophila throughout development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;260:707–711. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng SC, Perkins LA, Conboy G, Perrimon N, Fishman MC. A Drosophila gene expressed in the embryonic CNS shares on conserved domain with the mammalian GAP-43. Development. 1989;105:629–638. doi: 10.1242/dev.105.3.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masai I, Okazaki A, Hosoya T, Hotta Y. Drosophila retinal degeneration A gene encodes an eye-specific diacylglycerol kinase with cysteine-rich zinc-finger motifs and ankyrin repeats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11157–11161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masai I, Hosoya T, Kojima S, Hotta Y. Molecular cloning of a Drosophila diacyglycerol kinase gene that is expressed in the nervous system and muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6030–6034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.6030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendena WG, Garbe JC, Traverse KL, Lakhotia SC, Pardue ML. Multiple inducers of the Drosophila heat shock locus 93D (hsr omega):inducer-specific patterns of the three transcripts. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:2017–2018. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.6.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakhotia SC, Sharma A. The 93D (hsr-omega) locus of Drosophila: non-coding gene with house-keeping functions. Genetica. 1996;97:339–348. doi: 10.1007/BF00055320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhmanova A, Meidema K, Wang Y, van Bruggen M, Berden JH, Moudrianakis EN, Hennig W. The localization of histone H3.3 in germ line chromatin of Drosophila males as established with a histone H3.3-specific antiserum. Chromosoma. 1997;106:335–347. doi: 10.1007/s004120050255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhmanova AS, Bindels PC, Xu J, Miedema K, Kremer H, Hennig W. Structure and expression of histone H3.3 genes in Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila hydei. Genome. 1995;38:586–600. doi: 10.1139/g95-075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth SC, Rosenthal LS, Kammermeyer KL, Potter MB, Nelson DJ. Expression of a Drosophila melanogaster acetylcholine receptor-related gene in the central nervous system. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:778–785. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.2.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DN, Smith-Leiker TA, Sokol NS, Hudson AM, Cooley L. Formation of the Drosophila ovarian ring canal inner rim depends on cheerio. Genetics. 1997;145:1063–1072. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.4.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georges-Labouesse E, Mark M, Messaddeq N, Gansmuller A. Essential role of alpha 6 integrins in cortical and retinal lamination. Curr Biol. 1998;8:983–936. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70402-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu S, Cavener DR. Isolation and characterization of the Drosophila melanogaster eIF-2 alpha gene encoding the alpha subunit of translation initiation factor eIF-2. Gene. 1994;140:239–242. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90550-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoyo J, Alcalde J, Mendez R, Pulido D, de Haro C. Cloning and characterization of a cDNA encoding a protein synthesis initiation factor-2alpha (eIF-2alpha) kinase from Drosophila melanogaster. Homology to yeast GCN2 protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12544–12550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun XH, Tso JY, Lis J, Wu R. Differential regulation of the two glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene during Drosophila development. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:5200–5205. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.12.5200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B, Shortridge RD, Seong C, Oh Y, Baek K, Yoon J. Molecular characterization of a novel Drosophila gene which is expressed in the central nervous system. Mol Cells. 1998;8:750–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, McKay RR, Miller K, Shortridge RD. Multiple subtypes of phospholipase C are encoded by the norpA gene of Drosophila melanogaster. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14376–14382. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.24.14376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekelsky JJ, Brodsky MH, Rubin GM, Hawley RS. Drosophila and human RecQ5 exist in different isoforms generated by alternative splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3762–3769. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.18.3762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]