Abstract

Most potent anti-retroviral drugs (e.g., HIV-1 protease inhibitors) poorly penetrate the blood-brain barrier. Brain distribution can be limited by the efflux transporter, P-glycoprotein (P-gp). The ability of a novel drug delivery system (block co-polymer P85) that inhibits P-gp, to increase the efficacy of anti-retroviral drugs in brain was examined using a severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mouse model of HIV-1 encephalitis (HIVE). SCID mice inoculated with HIV-1 infected human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) into the basal ganglia were treated with P85, anti-retroviral therapy (ART) [zidovudine, lamivudine and nelfinavir, (NEL)], or P85 and ART. Mice were sacrificed on days 7 and 14, and brains were evaluated for levels of viral infection. Anti-viral effects of NEL, P85 or their combination were evaluated in vitro using HIV-1 infected MDM and demonstrated anti-retroviral effects of P85 alone. In SCID mice injected with virus-infected MDM the combination of ART-P85 and ART alone showed a significant decrease of HIV-1 p24 expressing MDM (25% and 33% of controls, respectively) at day 7 while P85 alone group was not different from control. At day 14, all treatment groups showed a significant decrease in percentage of HIV-1 infected MDM as compared to control. P85 alone and combined ART-P85 groups showed the most significant reduction in percentage of HIV-1 p24 expressing MDM (8–22% of control) that were superior to the ART alone group (38% of control). Our findings indicate major anti-retroviral effects of P85 and enhanced in vivo efficacy of antiretroviral drugs when combined with P85 in a SCID mouse model of HIVE.

Introduction

Resistance to antiretroviral compounds such as the anti-HIV-1 protease inhibitors can develop and HIV-1 levels rapidly rebound to pretreatment levels if anti-retroviral therapy (ART) is discontinued. The appearance of resistance and virus resurgence are related to the limited transport of anti-retroviral drugs across tissue barriers and formation of virus reservoirs in long living cells (like macrophages). The blood-brain barrier (BBB) restricts the passage of macromolecules and a number of therapeutic agents, creating an immunological and pharmacological sanctuary site for HIV-1 in the brain and spinal cord (Aweeka et al. 1999; Pomerantz 2002). There is growing evidence indicating that transport proteins expressed at the BBB also regulate penetration of anti-retroviral drugs into the central nervous system (CNS). Allelic variants and inhibition (or induction) of these transporters are determinants of active drug present in the cell (Fellay et al. 2002). One of these transport proteins, a membrane-associated ATP-dependent efflux transporter, P-glycoprotein (P-gp), is expressed on brain microvascular endothelial cells, and it limits entry into the brain of numerous xenobiotics, including HIV-1 protease inhibitors. In addition, the expression of P-gp was recently demonstrated in brain parenchyma cells, such as resident brain macrophages, the microglia (Lee et al. 2001). Thus, the cellular membranes of brain macrophages may act as an additional “barrier” to drug permeability (Bendayan et al. 2002). This may be important in the treatment of HIV-1 infection of the CNS where macrophages and microglia are the main reservoir for virus (Persidsky and Gendelman 2003). P-gp is down-regulated on brain microvascular endothelial cells during HIVE (Persidsky et al. 2000). However, P-gp up-regulation was demonstrated in brain macrophages during HIVE and in HIV-1 infected macrophages in vitro (Langford et al. 2004; Persidsky et al. in press). P-gp decreased protease inhibitor uptake by HIV-1 infected CD4+ T lymphocytes (Jones et al. 2001), and it has been previously shown that the protease inhibitors ritonavir, saquinavir, indinavir, amprenavir and nelfinavir are substrates for P-gp (Choo et al. 2000; Kim et al. 1998; Lee et al. 1998; Polli et al. 1999). If enhanced levels of anti-retroviral drugs are to penetrate the BBB into the CNS, inhibition of active efflux components, including P-gp, appear to be necessary (Huisman et al. 2001; Kim et al. 1998).

Potentially important P-gp inhibitors are known and include the Pluronic block co-polymers such as P85. Prior studies on cells derived from multi-drug resistant tumors demonstrated that Pluronics can inhibit the P-gp efflux pump, thereby increasing accumulation of drug in cancer cells (Alakhov et al. 1996). Such effects could be due to interactions of the Pluronic with the membrane or ATPase function necessary for P-gp efflux activity (Alakhov et al. 1996; Slepnev et al. 1992). P85 has been shown to diminish ATPase activity in cell membranes expressing P-gp (Batrakova et al. 2001a). P85 inhibits P-gp on the BBB in vivo as demonstrated by increased concentrations of digoxin (a well-known substrate for P-gp) in mouse CNS (Batrakova et al. 2001b). Although increased penetration of the protease inhibitor, nelfinavir, into brain was shown by P-gp inhibition in mice (Choo et al. 2000), there have been no reports on the efficacy of anti-retroviral drugs with P-gp inhibition on HIV-1 replication in brain.

The use of animal models to monitor anti-retroviral efficacy in the brain is crucial to screening anti-retroviral regimens (McArthur and Kieburtz 2000). Ascertaining the efficacy of anti-HIV-1 formulations has been made possible by the use of the severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mouse model for HIVE which was developed in our laboratories (Persidsky et al. 1996). This has proven of significant value in testing anti-retroviral and adjunctive therapies for HIV disease within the CNS (Dou et al. 2003; Limoges et al. 2000; Limoges et al. 2001; Persidsky et al. 2001). SCID mice, injected in the basal ganglia with human HIV-1-infected monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM), demonstrate cognitive, behavioral, electrophysiological, immune and histopathological features of human disease (Anderson et al. 2003; Persidsky et al. 1997; Persidsky et al. 1996; Zink et al. 2002). The HIVE SCID mouse model allows the spreading of viral infection in MDM behind an intact BBB, and it was utilized for efficacy testing of anti-retroviral agents (Limoges et al. 2000; Limoges et al. 2001). To explore the idea that inhibition of efflux will enhance the efficacy of anti-HIV drugs, we assessed whether P-gp inhibition by the Pluronic block copolymer P85 could enhance the efficacy of a protease inhibitor (NEL) in vitro in HIV-1 infected MDM and the efficacy of ART (including AZT, 3TC and NEL) in HIVE SCID mice. The current study showed enhanced CNS efficacy of anti-retroviral drugs when combined with P85. Our experiments also demonstrated that there is a significant anti-retroviral effect of the block copolymer P85 both in vitro and in vivo, which warrants further investigation.

Materials and Methods

Isolation, culture and virus infection of human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM)

Human monocytes were isolated from HIV-1,2 and hepatitis B seronegative donors and purified by counter-current centrifugal elutriation (Gendelman et al. 1988). Monocytes were cultured in 96-well plates or Teflon flasks 2 × 106 cells/mL in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) with 10% heat inactivated human serum, 1% glutamine, 50 μg/mL gentamicin (Sigma), 10 μg/mL ciprofloxacin (Sigma), and 1,000 U/mL human macrophage colony-stimulating factor (MCSF) (a generous gift from Genetics Institute, Inc., Cambridge, MA). After 7 days in suspension culture, MDM were infected with the macrophage-tropic viral strain HIV-1ADA at an MOI of 0.01 infectious viral particles/target cell (Gendelman et al. 1988).

Assay of progeny virion production

Reverse transcriptase (RT) activity was determined in triplicate with culture fluids added to 0.05% Nonidet P-40 (Sigma), 10 μg/mL poly(A), 0.25 μg/mL oligo(dt) (Pharmacia Fine Chemicals, Piscataway, NJ), 5 mM dithiothreitol Thymidine 5'-Triphosphate (2 Ci/mmol; Amersham Corp., Arlington Heights, IL) in pH 7.9 Tris-HCL buffer for 24 hours at 37°C. Radiolabeled nucleotides were precipitated with cold 10% trichloroacetic acid and 95% ethanol in an automatic cell harvester (Skatron Inc., Sterling, VA) on paper filters. Radioactivity was determined by scintillation spectroscopy. RT results were normalized to cell numbers by measuring cell viability at the end of the sample collection by MTT assay (Limoges et al. 2000).

Effect of P85 on BBB integrity in vivo

In order to determine if P85 has a non-specific effect on BBB permeability, particularly examining effects on paracellular transport and tight-junction integrity, the CNS distribution of a probe molecule, 3H-mannitol, was determined with and without the co-treatment of P85. FVB mice (male FVB, 12–14 weeks old) were purchased from Taconic (Germantown, NY). Mice received a tail-vein injection (100 μL) of 20μCi 3H-mannitol in saline with or without 1% P85. At selected time points after injection, 0.5, 2, 3, and 4 hours, four mice at each time point were sacrificed and serum and whole brain (homogenate) were collected for liquid scintillation counting.

SCID HIVE model

SCID mice (male C.B-17/IcrCrl-scidBR, 3 to 4 weeks old) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Animals were housed in sterile microisolator cages under pathogen free conditions in the Department of Comparative Medicine at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in accordance with ethical guidelines for the care of animals set forth by the National Institutes of Health. Human MDM for mouse injections were cultured in suspension in 250 mL Teflon flasks (1.5 × 108 cells per flask) and infected with the HIV-1ADA at MOI of 0.01 infectious viral particles/target cell for six hours. Eighteen hours after virus infection, animals were stereotactically inoculated with 15 μl of cell suspension containing 3.0 × 105 HIV-1-infected cells (in serum free DMEM) into the left hemisphere with coordinates previously determined (Persidsky et al. 1996). Intracranial inoculations of HIV-1ADA infected MDM were performed following anesthesia (intraperitoneal injections of 100 mg/kg ketamine and 16 mg/kg xylazine). Animals were sacrificed at 7 or 14 days after inoculation for immunohistochemical analyses.

Drug treatment of HIVE mice

Mice received ART [AZT (20 mg/kg/day), 3TC (20 mg/kg/day) and NEL (50 mg/kg/day)] via intraperitoneal injections (twice a day). Drug administration was started one day before the infected MDM were injected and continued at the identical dosing regimen until animal sacrifice. To demonstrate specificity of the P85 P-gp mediated effect, control animals and animals treated with ART received another Pluronic block copolymer, F127, that had no effect on P-gp function (Batrakova et al. 2003) as a control for P85. Four treatment groups in the first experiment were as follows: control (untreated, 1% F127 Pluronic only, n=6), 1% F127 and ART (n=6), 0.2% P85 (n=5) or 1% P85 with ART (n=5). In a subsequent experiment, the four treatment groups were: control (F127 Pluronic control only, n=10), F127 with ART (n=10), 0.2% P85 alone (n=10) and 0.2% P85 with ART (n=10).

Immunohistochemical analyses

Tissue was fixed in 4% phosphate buffered paraformaldehyde and paraffin embedded. Immunohistochemistry was performed on 5μm paraffin sections. Human MDM were identified immunohistochemically with anti-vimentin mAbs (1:1000 Boehringer Mannheim). The level of infection in MDM was assessed using anti-HIV-1 p24 mAbs (Dako, 1:10). Mouse astrocytes were recognized with polyclonal Abs against glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP; 1:1000, Dako). Structural tightness of the BBB was evaluated by immunostaining with Abs to occludin and claudin-5 (tight junction proteins expressed on brain microvascular endothelium, 1:25 and 1:50, respectively, Zymed Laboratories). To detect primary Abs (vimentin, GFAP, HIV-1 p24, claudin-5 and occludin) on paraffin sections, immunoperoxidase staining was performed (Vectastain Elite ABC kit, Vector Laboratories) with 3,3'-diaminobenzidine as the chromogen. All sections were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin. Deletion of the primary antibody or use of mouse IgG or rabbit IgG (Dako) served as controls. Immunostained tissues were analyzed with a Nikon Eclipse 800 microscope.

For histologic analysis, 40 initial sections (20 sections each from two blocks) were cut from each mouse brain, and every 6th section was stained for GFAP to identify the site of injection as described (Limoges et al. 2000; Limoges et al. 2001). Every 7th section was stained for vimentin to detect human MDM. If the injection site or the presence of human cells was not determined, 30 more sections were cut until the injection site was determined or all of the tissue was sectioned. Each brain section containing MDM and a paired section were labeled with antibody to HIV-1 p24 antigen to generate the percentage of HIV-1-infected MDM. Results were averaged for each mouse and treatment group.

Statistical Analysis

In vitro data were analyzed by Microsoft Excel 2002 using the two-tailed nonparametric t-test. A minimum p value of 0.05 was estimated as significant for all tests. In vivo statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software with using the two-tailed nonparametric t-test and two-way ANOVA with Newman-Keuls post-test for multiple comparisons. All in vitro and in vivo data are presented as mean ± standard error of mean (SE).

Results

Effects of P85 in vitro

Since mononuclear phagocytes (macrophages and microglia) are the predominant cell type infected in the human brain (Koenig et al. 1986), we first analyzed the anti-retroviral effects of P85 in combination with the protease inhibitor NEL in vitro in human MDM infected with HIV-1ADA (a macrophage-tropic strain). We first established what concentrations of P85 are cytotoxic for MDM in vitro. Using the MTT assay, we demonstrated that P85 significantly decreased MDM viability at concentrations >0.1% while lower concentrations were not cytotoxic over a period of two weeks (data not shown).

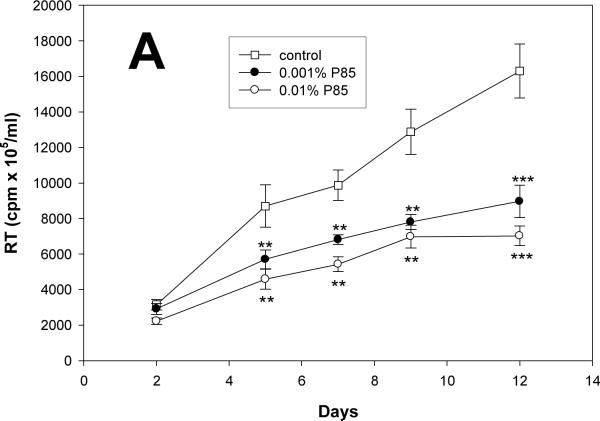

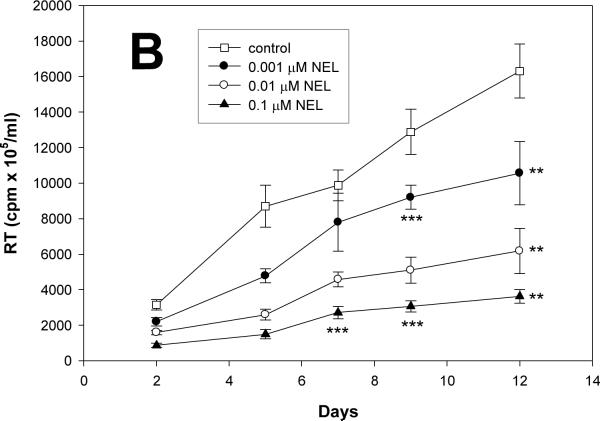

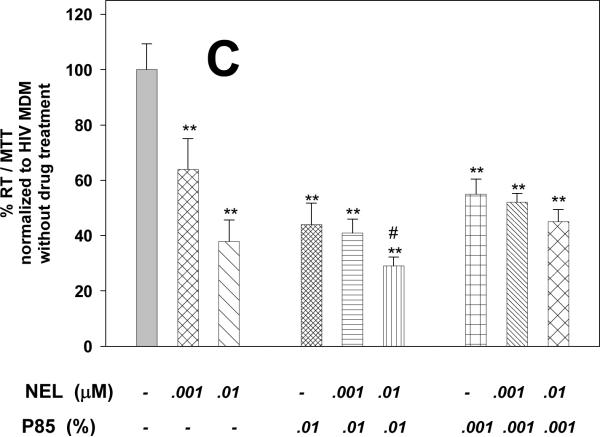

Potential anti-retroviral activities of P85 alone were next investigated at concentrations from 0.001 to 0.01%, those known not to elicit cytotoxicity. NEL alone administered at concentrations from 0.001 to 0.1 μM served as a positive control. Progeny virion production from infected cells was analyzed by RT activity over a period of 12 days. As seen in Fig. 1A (RT activity adjusted to MTT), P85 at concentrations from 0.001 to 0.01% decreased HIV-1 replication without any evidence of cytotoxicity. P85 showed significant inhibition of viral replication from day 5 (p<0.01) until day 12 (p<0.001), as compared to control. NEL administered at concentrations of 0.001, 0.01 and 0.1 μM showed significant anti-retroviral effect from day 5 (p<0.001) to day 12 (p<0.01) when compared to untreated MDM. NEL administered at a concentration of 0.001 μM was able to decrease viral replication on days 5, 9 and 12 (p<0.01) (Fig. 1B). Lower concentrations of NEL had little effect on viral growth in these assays (data not shown).

Figure 1. Pluronic block co-polymer P85 inhibits HIV-1 replication in MDM.

(A) Effect of P85 and (B) NEL on HIV-1 replication in MDM as detected by reverse transcriptase (RT) activity over 12 days. (C) Effect of combined treatment with NEL (0.01μM and 0.001μM) and P85 (0.01% and 0.001%) on HIV-1 replication in MDM as detected by RT activity at day 12, normalized to control cells. ** p<0.01, ***p<0.001, # p<0.05 NEL+P85 as compared to NEL (0.01μM) or P85 (0.01%) alone. Results are presented as means+/-SE.

Because of the significant anti-viral effect of P85 alone shown in our initial experiment, we again examined P85 alone in a separate experiment at concentrations from 0.01 to 0.001% and combined with NEL at concentrations 0.01 to 0.001 μM at day 12. The P85 alone group, as seen in Fig. 1C, confirmed a significant (p<0.001) anti-viral effect with 0.001% P85, reducing HIV-1 replication to 55% of the control, and 0.01% P85 had a similar effect, reducing growth to 44% as compared to control at day 12 in this analysis. NEL at concentrations 0.01 and 0.001 μM suppressed viral replication to 64 and 38% of control, respectively. NEL at concentrations 0.01 and 0.001 μM combined with 0.001% of P85 decreased RT levels 52 and 45% of control untreated cells, respectively. P85 at a concentration of 0.01% in combination with 0.001 μM and 0.01 μM of NEL diminished virus replication to 41 and 29% of control. P85 in combination with NEL demonstrated an additional inhibitory effect in high doses (0.01% P85 and 0.01 μM NEL) when compared to pluronic or protease inhibitor alone. Results of these experiments demonstrated the significant anti-viral effect of P85 alone and the presence of an enhanced effect of NEL when combined with P85 at the highest tested concentration (0.01% P85).

Effects of P85 on BBB integrity

The brain-to-blood ratio of tritated mannitol was determined with and without P85 co-treatment. Mannitol can be used as a permeability marker because it has a very low permeability across the BBB due to intact tight junctions, and in the time frame of the experiment, this probe molecule will have limited brain penetration as long as tight junctions are not compromised. As seen in Fig. 2, the co-administration of P85 did not dramatically enhance the distribution of mannitol into the brain, indicting that P85 did not influence the BBB integrity. The brain-to-blood area under the curve ratio was 8% in the control case and 10% in the P85-treated case.

Figure 2. Effect of P85 on the integrity of the mouse BBB.

Concentration-time profile of radiolabeled mannitol in the whole brain homogenate (squares) and the serum (circles) of mice. Tracer administered intravenously in saline (open symbols) or in 1% P85 in saline (closed symbols). Data are expressed as mean +/- SD.

Anti-retroviral effects of P85 and ART in the SCID HIVE mouse model

We next utilized the HIVE SCID mouse model to compare the efficacy of a protease inhibitor-containing ART regimen with and without P85 on HIV-1 replication in brain. This model recapitulates the pathological and pathophysiological features of human HIVE [including giant cell encephalitis, neuronal injury, neuroinflammatory responses and cognitive abnormalities demonstrated in human disease (Persidsky et al. 1996; Zink et al. 2002)]. Moreover, the model allows testing of anti-retroviral drugs for therapeutic efficacy in preventing viral spread in a BBB protected CNS (Limoges et al. 2000; Limoges et al. 2001).

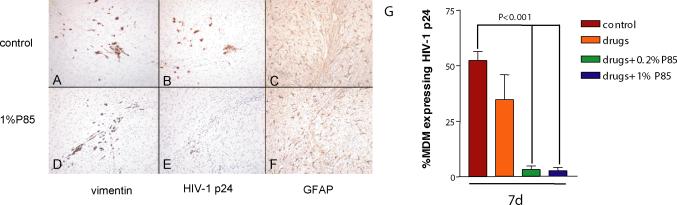

First, we examined the effect of ART [AZT (20 mg/kg/day), 3TC (20 mg/kg/day) and NEL (50 mg/kg/day)] with or without P85 (concentrations of 0.2 or 1.0%, corresponding to <0.01 and <0.05% in peripheral blood, assuming simple dilution by blood volume). No toxic effects (including weight loss, appearance of animals) were detected in animals treated with ART, P85 alone or the combination of both. MDM were infected for a longer period of time (six hours) than in our previous experiments in order to ensure high levels of infection and to detect effects of P85. HIV-1 p24 antigen positive cells were detected in serial sections and the percentage of immunopositive cells averaged for each treatment group. Equal numbers of MDM were detected in the brains of animals in each of the groups (Fig. 3A,D). There was no significant difference in percentage of HIV-1 p24 positive MDM between control mice (52±8.9%) and the drug-only group (36±11.4%) at day 7 (Fig. 3,G), while the level of infection was dramatically lower when compared to control in both groups when ART were combined with P85 at 0.2% or 1.0% (3.3±3.4% and 2.8±3.4%, p<0.001 and p<0.001, respectively; Fig. 3B,E,G).

Figure 3. Effect of triple drug combination (ART) with P85 (0.2% and 1%) on viral replication in HIVE SCID mice.

Equal numbers of MDM were detected in the brain tissue of control (A) and treated mice (AZT/3TC/NEL and P85, 1%)(D). Treatment significantly decreased the percent of cells expressing HIV-1 p24 (E) as compared to control animals (B). There was no difference in the level of astrogliosis in control mice (C) vs. the treated group (F). Histologic data from all mice were analyzed and the percent of MDM-expressing HIV-1 p24 was averaged for each treatment group (G). Immunostaining with Abs to vimentin (panels A,D), HIV-1 p24 (B,E), and GFAP (C,F). Original magnification panels A–F is ×200. Bar values represent means+/-SE.

Our second in vivo study was performed to address the issue of possible anti-viral effects of P85 alone (as indicated by our in vitro data); and to corroborate the results of the first in vivo experiment. In the second in vivo study, P85 was examined only at the lower concentration of 0.2% alone or in combination with ART. The anti-retroviral drugs were dosed in the same concentrations [AZT (20 mg/kg/day), 3TC (20 mg/kg/day) and NEL (50 mg/kg/day)] as the first experiment. Figure 4 demonstrates results (the percent of MDM positive for HIV-1 p24 averaged for each treatment group) at days 7 and 14. The spread of virus infection between human MDM in mouse brain occurred effectively, and 39.9±10.3% and 68.5±7.9% of MDM were HIV-1 p24 positive at day 7 and day 14. At day 7, the combined ART with 0.2% P85 group showed a significant decrease of infected MDM (9.4±8.6% versus 39.9% in control, p<0.001). The group treated with ART alone also showed significant decrease in the level of infection (13.1+3.5%, p=0.028) as compared to control, while the P85 alone group was not significantly different from control (p>0.05). At day 14, all treatment groups featured a significant diminution in the level of infection as compared to control. Although the ART reduced the percent of HIV-1 p24-positive cells (35.3±5.6%, p<0.001), the most notable effect was achieved in the 0.2% P85 alone group (13.4±5.6%, p<0.001) and the combined ART + 0.2% P85 group (7.0±10.0%, p<0.001) when compared to control (68.5±7.9%) (Fig. 4,A–H). The anti-retroviral effect seen in these groups was greater than the ART group for 0.2% P85 alone (p<0.01) and for the combined ART + 0.2% P85 group (p<0.05).

Figure 4. Effect of P85 (0.2%) and triple drug combination (ART) on viral replication in HIVE SCID mice.

At day 7, the combined ART-P85 and ART alone groups showed a significant decrease of HIV-1 p24 expressing MDM (9% and 13%, resp.) while the P85 alone was not different from control. At day 14, the most notable effects were seen in the P85 alone group and the combined drug/P85 group (6–15% of HIV-1 p24-positive MDM), which were superior to the NEL/AZT/3TC (ART) group (35% p24-positive cells). Histologic data from all mice was analyzed and the percent of MDM expressing HIV-1 p24 was averaged for each treatment group. Bar values represent means+/-SE.

We next evaluated neuro-inflammatory responses (astrogliosis) and preservation of the BBB in the SCID mice. This was done first to evaluate drug toxicity and second to determine the relationships between viral inhibition and neuropathology. The level of astrogliosis (as detected by GFAP staining) was not altered in different treatment groups as compared to control (Fig. 3,C,F). Moreover, there was no evidence of BBB disruption with respect to the expression and distribution of tight junction proteins (claudin-5 and occludin) at any time point regardless of treatment, as assessed by immunostaining in brain microvascular endothelial cells of the SCID mice (Fig. 5,I–L). These results indicate the absence of significant toxic effects on the BBB of P85 in the doses used in our experiments. Moreover, prior to any dosing of ART or P85, we examined the effect of twice-daily intraperitoneal injections for 14 days of saline control, 0.2% and 1% P85 solutions on animal weights. There were no significant differences in the weights of the mice amongst all treatment groups (data not shown).

Figure 5. Effect of P85 (0.2%) and triple drug combination (ART) on viral replication in HIVE SCID mice.

Immunostaining with Abs to vimentin (panels A–D), HIV-1 p24 (E–H), and claudin-5 (I–L). Equal numbers of MDM were detected in the brain tissue of animals from control (A), ART (AZT/3TC/NEL) (B), P85 (C) and ART plus P85 groups (D). Treatment with P85 (G) or ART+P85 (H) at day 14 significantly decreased the percentage of cells expressing HIV-1 p24 as compared to control animals (E) or ART alone (F). There was no evidence of BBB disruption as indicated by continuous claudin-5 staining on brain endothelial cells in control (I), ART (J), P85 (K) or ART+P85 groups (L). Original magnification panels A–L is ×400.

Discussion

Despite the diminished incidence of HIV-1 associated-dementia in the ART era (Maschke et al. 2000), the greater life expectancy of infected individuals has resulted in an increased prevalence of disease. Anti-retroviral failures occur commonly and represent a particular problem for treatment of brain infection. Indeed, inefficient penetration of anti-retroviral drugs into the CNS and ART failure de novo could contribute to viral mutation and sustained viral replication in brain (Jellinger et al. 2000; Sacktor et al. 2001). Therefore, development of new approaches to improve the CNS delivery and efficacy of ART (including novel drug delivery systems) is necessary to improve the targeted efficacy of current drug therapies within the brain sanctuary. Our initial investigation began with the objective of determining if the inclusion of the block co-polymer P85 could improve efficacy of ART. Previous studies with HIV-1 protease inhibitors showed that P-gp could alter the distribution of NEL across the BBB and that inhibition of P-gp increased the brain levels of NEL to plasma levels in mice (Choo et al. 2000; Kim et al. 1998; Savolainen et al. 2002). However, to date, no study has been reported that examined the efficacy of combination HIV-1 anti-viral drugs and P-gp inhibition in human HIV-1 infected macrophages (the main cell type infected in human brain tissue) located behind an intact, functioning BBB.

P85 was chosen as the P-gp inhibitor based upon previous in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrating that P85 treatment increased the permeability of P-gp substrates across primary cultures of bovine brain microvessel endothelial cells (Batrakova et al. 1999) and increased the brain penetration of digoxin (a known P-gp substrate) in mice to a comparable degree as seen in P-gp knockout mice (Batrakova et al. 2001b). The protease inhibitor NEL, with poor CNS penetration, is part of current ART regimens. Our in vitro study demonstrated that NEL significantly lowered HIV-1 replication in human MDM when compared to control untreated cells. An unexpected result was the previously unknown antiviral effect of P85 when administered independently of NEL. The combination of P85 with NEL was no more efficient in decreasing HIV-1 replication when compared to the NEL alone group, with the exception of the 0.01μM NEL-0.01%P85 group, which showed a significant enhanced effect (see Fig.1C). These results suggest that P85 has significant anti-retroviral effect in non-toxic concentrations.

To confirm these in vitro observations, we utilized the SCID mouse model for HIVE where spread of HIV-1 infection between human MDM was demonstrated (Limoges et al. 2000). This model was previously used for comparative assessment of different anti-retroviral drugs by measurements of viral load and numbers of infected human macrophages (Limoges et al. 2000; Limoges et al. 2001). Our first in vivo experiment demonstrated that the combination of P85 (0.2 and 1%) with ART (AZT, 3TC and NEL) in doses used effectively in humans suppressed viral replication at significantly higher levels when compared to triple drug therapy alone. Importantly, the control group and drug only group were treated with another block co-polymer (F-127), which lacks P-gp inhibitory properties (Batrakova et al. 2003). These results supported our initial idea that P-gp inhibition can result in efficient drug delivery across the BBB in the setting of HIV-1 infection. Because of the major reduction of viral replication detected in the first in vivo experiment with the combination of ART plus P85 and the unexpected effect of P85 in the in vitro experiment, a second in vivo experiment was designed to determine the effect of P85 alone. It included the same control, drug combination alone, and the combination of ART with 0.2% P85, but with the addition of a 0.2% P85 alone group. Similar to our first in vivo study, there was a decrease in the percentage of HIV-1 virus in MDM with the combination drugs and drugs combined with 0.2% P85 at days 7 and 14. The important finding was that P85 alone was able to suppress viral replication in MDM by day 14. Of note, no significant toxic effects or signs of BBB breakdown were found in any of the treatment groups in vivo.

Our results show that the inhibition of P-gp using the copolymer P85 may have effects other than just increasing the penetration and efficacy of anti-retroviral drugs into the CNS. Recent studies indicated that P-gp could play an important role in HIV-1 replication due to the association of P-gp with glycolipid membrane domains (Speck et al. 2002). Both viral infection and HIV-1 budding occur in cholesterol-enriched microdomains, known as lipid “rafts” (Ono and Freed 2001; Popik et al. 2002). It has been suggested that cellular receptors used by HIV-1 to infect macrophages (CD4 and CCR5) are located within lipid-rich rafts (Ono and Freed 2001; Popik et al. 2002). Since the effects of P85 on plasma membranes have been shown to include decreased microviscosity of the membrane (Batrakova et al. 2003), this co-polymer may disrupt rafts and influence receptor distribution. Of note, P-gp is predominately localized in these cholesterol-enriched areas (Luker et al. 2000). Furthermore, P-gp mediates the ATP-dependent relocation of cholesterol from the cytosolic leaflet to the exoplasmic leaflet of the plasma membrane (Garrigues et al. 2002). Therefore, we hypothesize that the decrease in HIV-1 replication with 0.2% P85 alone may be caused by an interaction with P-gp or directly with the glycolipid enriched rafts. This hypothesis requires further investigation.

The in vivo anti-HIV1 activity of P85 in the CNS strongly suggests that P85 crosses the blood brain barrier. This was confirmed in a recent study of the biodistribution of radiolabeled P85 in the mouse (Batrakova, et al. 2004). In that study, the distribution of P85 to the brain was proportional to an intravenous dose of 100μL 0.02%, 0.2% and 1.0% P85 injected as a bolus in the tail vein.

One advantage of using the Pluronic block copolymer P85 as a P-gp inhibitor is that potentially it has two mechanisms of action (Batrakova et al. 2001a). As reported by Batrakova and colleagues (Batrakova et al. 2001a), P85 decreased ATP levels in bovine brain endothelial cell monolayers, an effect which would be important due the need for ATP for the late stage processing of HIV-1 (Tritel and Resh 2001). The structure of lipid bilayers can also be affected by P85 because of absorption of the block copolymer molecules in the membrane, which may lead to the destabilization of P-gp (Batrakova et al. 2001a). It is feasible that the P85-mediated anti-viral effect seen in our in vitro and in vivo experiments could be associated with destabilization of lipid rafts. Alteration of the lipid membrane environment has been shown to be crucial to the function of P-gp (Romsicki and Sharom 1999). Membrane fluidization by various agents such as Tween 20, Nonidet P-40 and Triton X-100, has also been shown to inhibit of P-gp efflux (Regev et al. 1999).

Discrepant results of our in vitro experiments (i.e., the absence of enhanced effect of NEL combined with P85 except at the high concentrations) and the increased in vivo efficacy of the P85 and ART combination could be related to the inhibition of other efflux transporters on the BBB by P85. These include multi drug resistant-associated proteins 4 and 5 (MRP4, MRP5) present on BBB and breast cancer resistant protein (BCRP) which has been recently shown on brain microvascular endothelial cells (Eisenblatter et al. 2003; Zhang et al. 2003) and brain macrophages (Persidsky et al. in press). This possibility and other potential mechanisms underlying the anti-HIV-1 effect of P85 are currently under investigation in our laboratories.

The early rationale of using inhibitors of P-gp with HIV-1 protease inhibitors was to increase their limited distribution across biological barriers into HIV-1 sanctuary sites such as the CNS (Choo et al. 2000; Kim et al. 1998; Savolainen et al. 2002). This study for the first time indicates that P-gp inhibition may also be important in decreasing HIV-1 replication and is concordant with current understanding of cellular requirements for HIV-1 replication (Speck et al. 2002; Tritel and Resh 2001). We demonstrated that P-gp inhibition may not only increase efficacy by increasing drug distribution into blood-tissue barriers of HIV-1 virus, but that P85 itself could also have an anti-retroviral effect in particular cell targets (like macrophages) serving as a viral reservoir in the CNS. In this regard, further studies are needed to examine the drug concentrations of the anti-retrovirals in the brain to determine if P85 may increase penetration of ART to the brain. The possible dual inhibitory nature of P85, either by ATP depletion or membrane fluidization, also needs to be clarified. This study presents a new direction to solve problems of anatomical and cellular sanctuary sites for HIV-1 replication (Pomerantz 2002; Schrager and D'Souza 1998).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Ms. Robin Taylor for excellent editorial support.

This work was supported in part by R01 NS 42549-01A1 (WE, YP), 2RO1 NS36229-01 (AK) and P20 RR 15635-03 (YP).

Abbreviations used are

- AZT

zidovudine

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- CNS

central nervous system

- NEL

nelfinavir

- 3TC

lamivudine

- HAD

HIV-1-associated dementia

- HIVE

HIV-1 encephalitis

- ART

active antiretroviral therapy

- MDM

monocyte-derived macrophages

- P-gp

P-glycoprotein

- SCID

severe combined immunodeficiency

References

- Alakhov V, Moskaleva E, Batrakova EV, Kabanov AV. Hypersensitization of multidrug resistant human ovarian carcinoma cells by pluronic P85 block copolymer. Bioconjug Chem. 1996;7:209–216. doi: 10.1021/bc950093n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson ER, Boyle J, Zink WE, Persidsky Y, Gendelman HE, Xiong H. Hippocampal synaptic dysfunction in a murine model of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 encephalitis. Neuroscience. 2003;118:359–369. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00925-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aweeka F, Jayewardene A, Staprans S, Bellibas SE, Kearney B, Lizak P, Novakovic-Agopian T, Price RW. Failure to detect nelfinavir in the cerebrospinal fluid of HIV-1--infected patients with and without AIDS dementia complex. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1999;20:39–43. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199901010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batrakova E, Lee S, Li S, Venne A, Alakhov V, Kabanov A. Fundamental relationships between the composition of pluronic block copolymers and their hypersensitization effect in MDR cancer cells. Pharm Res. 1999;16:1373–1379. doi: 10.1023/a:1018942823676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batrakova EV, Li S, Alakhov VY, Miller DW, Kabanov AV. Optimal structure requirements for pluronic block copolymers in modifying P-glycoprotein drug efflux transporter activity in bovine brain microvessel endothelial cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:845–854. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.043307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batrakova EV, Li S, Vinogradov SV, Alakhov VY, Miller DW, Kabanov AV. Mechanism of pluronic effect on P-glycoprotein efflux system in blood-brain barrier: contributions of energy depletion and membrane fluidization. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001a;299:483–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batrakova EV, Miller DW, Li S, Alakhov VY, Kabanov AV, Elmquist WF. Pluronic P85 enhances the delivery of digoxin to the brain: in vitro and in vivo studies. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001b;296:551–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batrakova EV, Li S, Li Y, Alakhov VY, Elmquist WF, Kabanov AV. Distribution kinetics of a micelle-forming block copolymer Pluronic P85. J Controlled Rel. 2004;100:389–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendayan R, Lee G, Bendayan M. Functional expression and localization of P-glycoprotein at the blood brain barrier. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;57:365–380. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo EF, Leake B, Wandel C, Imamura H, Wood AJ, Wilkinson GR, Kim RB. Pharmacological inhibition of P-glycoprotein transport enhances the distribution of HIV-1 protease inhibitors into brain and testes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2000;28:655–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou H, Birusingh K, Faraci J, Gorantla S, Poluektova LY, Maggirwar SB, Dewhurst S, Gelbard HA, Gendelman HE. Neuroprotective activities of sodium valproate in a murine model of human immunodeficiency virus-1 encephalitis. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9162–9170. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-27-09162.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenblatter T, Huwel S, Galla HJ. Characterisation of the brain multidrug resistance protein (BMDP/ABCG2/BCRP) expressed at the blood-brain barrier. Brain Res. 2003;971:221–231. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02401-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellay J, Marzolini C, Meaden ER, Back DJ, Buclin T, Chave JP, Decosterd LA, Furrer H, Opravil M, Pantaleo G, Retelska D, Ruiz L, Schinkel AH, Vernazza P, Eap CB, Telenti A. Response to antiretroviral treatment in HIV-1-infected individuals with allelic variants of the multidrug resistance transporter 1: a pharmacogenetics study. Lancet. 2002;359:30–36. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrigues A, Escargueil AE, Orlowski S. The multidrug transporter, P-glycoprotein, actively mediates cholesterol redistribution in the cell membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10347–10352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162366399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendelman HE, Orenstein JM, Martin MA, Ferrua C, Mitra R, Phipps T, Wahl LA, Lane HC, Fauci AS, Burke DS, et al. Efficient isolation and propagation of human immunodeficiency virus on recombinant colony-stimulating factor 1-treated monocytes. J Exp Med. 1988;167:1428–1441. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.4.1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huisman MT, Smit JW, Wiltshire HR, Hoetelmans RM, Beijnen JH, Schinkel AH. P-glycoprotein limits oral availability, brain, and fetal penetration of saquinavir even with high doses of ritonavir. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:806–813. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.4.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellinger KA, Setinek U, Drlicek M, Bohm G, Steurer A, Lintner F. Neuropathology and general autopsy findings in AIDS during the last 15 years. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2000;100:213–220. doi: 10.1007/s004010000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K, Bray PG, Khoo SH, Davey RA, Meaden ER, Ward SA, Back DJ. P-Glycoprotein and transporter MRP1 reduce HIV protease inhibitor uptake in CD4 cells: potential for accelerated viral drug resistance? Aids. 2001;15:1353–1358. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200107270-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim RB, Fromm MF, Wandel C, Leake B, Wood AJ, Roden DM, Wilkinson GR. The drug transporter P-glycoprotein limits oral absorption and brain entry of HIV-1 protease inhibitors. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:289–294. doi: 10.1172/JCI1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig S, Gendelman HE, Orenstein JM, Dal Canto MC, Pezeshkpour GH, Yungbluth M, Janotta F, Aksamit A, Martin MA, Fauci AS. Detection of AIDS virus in macrophages in brain tissue from AIDS patients with encephalopathy. Science. 1986;233:1089–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.3016903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford D, Grigorian A, Hurford R, Adame A, Ellis RJ, Hansen L, Masliah E. Altered P-glycoprotein expression in AIDS patients with HIV encephalitis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:1038–1047. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.10.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CG, Gottesman MM, Cardarelli CO, Ramachandra M, Jeang KT, Ambudkar SV, Pastan I, Dey S. HIV-1 protease inhibitors are substrates for the MDR1 multidrug transporter. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3594–3601. doi: 10.1021/bi972709x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G, Schlichter L, Bendayan M, Bendayan R. Functional expression of P-glycoprotein in rat brain microglia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:204–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limoges J, Persidsky Y, Poluektova L, Rasmussen J, Ratanasuwan W, Zelivyanskaia M, McClernon D, Lanier E, Gendelman H. Evaluation of antiretroviral drug efficacy for HIV-1 encephalitis in SCID mice. Neurol. 2000;54:379–389. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limoges J, Poluektova L, Ratanasuwan W, Rasmussen J, Zelivyanskaya M, McClernon DR, Lanier ER, Gendelman HE, Persidsky Y. The efficacy of potent anti-retroviral drug combinations tested in a murine model of HIV-1 encephalitis. Virology. 2001;281:21–34. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luker GD, Pica CM, Kumar AS, Covey DF, Piwnica-Worms D. Effects of cholesterol and enantiomeric cholesterol on P-glycoprotein localization and function in low-density membrane domains. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8692. doi: 10.1021/bi005112h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maschke M, Kastrup O, Esser S, Ross B, Hengge U, Hufnagel A. Incidence and prevalence of neurological disorders associated with HIV since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69:376–380. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.69.3.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur JC, Kieburtz K. Of mice and men: a model of HIV encephalitis. Neurology. 2000;54:284–285. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono A, Freed EO. Plasma membrane rafts play a critical role in HIV-1 assembly and release. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13925–13930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241320298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persidsky Y, Buttini M, Limoges J, Bock P, Gendelman HE. An analysis of HIV-1-associated inflammatory products in brain tissue of humans and SCID mice with HIV-1 encephalitis. J Neurovirol. 1997;3:401–416. doi: 10.3109/13550289709031186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persidsky Y, Gendelman HE. Mononuclear phagocyte immunity and the neuropathogenesis of HIV-1 infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:691–701. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0503205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persidsky Y, Limoges J, McComb R, Bock P, Baldwin T, Tyor W, Patil A, Nottet HS, Epstein L, Gelbard H, Flanagan E, Reinhard J, Pirruccello SJ, Gendelman HE. Human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis in SCID mice. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:1027–1053. see comments. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persidsky Y, Limoges J, Rasmussen J, Zheng J, Gearing A, Gendelman HE. Reduction in glial immunity and neuropathology by a PAF antagonist and an MMP and TNFalpha inhibitor in SCID mice with HIV-1 encephalitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2001;114:57–68. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(00)00454-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persidsky Y, Ramirez S, Haorah J, Kanmogne GK. Blood brain barrier: Structural components and function under physiologic and pathologic conditions. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. doi: 10.1007/s11481-006-9025-3. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persidsky Y, Zheng J, Miller D, Gendelman HE. Mononuclear phagocytes mediate blood-brain barrier compromise and neuronal injury during HIV-1-associated dementia. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;68:413–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polli JW, Jarrett JL, Studenberg SD, Humphreys JE, Dennis SW, Brouwer KR, Woolley JL. Role of P-glycoprotein on the CNS disposition of amprenavir (141W94), an HIV protease inhibitor. Pharm Res. 1999;16:1206–1212. doi: 10.1023/a:1018941328702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz RJ. Reservoirs of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: the main obstacles to viral eradication. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:91–97. doi: 10.1086/338256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popik W, Alce TM, Au WC. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 uses lipid raft-colocalized CD4 and chemokine receptors for productive entry into CD4(+) T cells. J Virol. 2002;76:4709–4722. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.10.4709-4722.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regev R, Assaraf YG, Eytan GD. Membrane fluidization by ether, other anesthetics, and certain agents abolishes P-glycoprotein ATPase activity and modulates efflux from multidrug-resistant cells. Eur J Biochem. 1999;259:18–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romsicki Y, Sharom FJ. The membrane lipid environment modulates drug interactions with the P-glycoprotein multidrug transporter. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6887–6896. doi: 10.1021/bi990064q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacktor N, Lyles RH, Skolasky R, Kleeberger C, Selnes OA, Miller EN, Becker JT, Cohen B, McArthur JC. HIV-associated neurologic disease incidence changes:: Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, 1990–1998. Neurology. 2001;56:257–260. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savolainen J, Edwards JE, Morgan ME, McNamara PJ, Anderson BD. Effects of a P-glycoprotein inhibitor on brain and plasma concentrations of anti-human immunodeficiency virus drugs administered in combination in rats. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30:479–482. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.5.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrager LK, D'Souza MP. Cellular and anatomical reservoirs of HIV-1 in patients receiving potent antiretroviral combination therapy. Jama. 1998;280:67–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slepnev VI, Kuznetsova LE, Gubin AN, Batrakova EV, Alakhov V, Kabanov AV. Micelles of poly(oxyethylene)-poly(oxypropylene) block copolymer (pluronic) as a tool for low-molecular compound delivery into a cell: phosphorylation of intracellular proteins with micelle incorporated [gamma-32P]ATP. Biochem Int. 1992;26:587–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speck RR, Yu XF, Hildreth J, Flexner C. Differential effects of p-glycoprotein and multidrug resistance protein-1 on productive human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:332–340. doi: 10.1086/341464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tritel M, Resh MD. The late stage of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembly is an energy-dependent process. J Virol. 2001;75:5473–5481. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.12.5473-5481.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Bachmeier C, Miller DW. In vitro and in vivo models for assessing drug efflux transporter activity. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2003;55:31–51. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zink WE, Anderson E, Boyle J, Hock L, Rodriguez-Sierra J, Xiong H, Gendelman HE, Persidsky Y. Impaired spatial cognition and synaptic potentiation in a murine model of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 encephalitis. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2096–2105. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02096.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]