Abstract

Living organ donors – 50% of solid organ donors in the United States – represent a unique population who accept medical risk for the benefit of another. One of the main justifications for this practice has been respect for donor autonomy, as realized through informed consent. In this retrospective study of living donors, we investigate 2 key criteria of informed consent: (1) depth of understanding and (2) degree of voluntariness. In our survey of 262 living kidney donors 2 to 40 months post donation, we found that more than 90% understood the effects of living donation on recipient outcomes, the screening process, and the short-term medical risks of donation. In contrast, only 69% understood the psychological risks of donation; 52% the long-term medical risks of donation; and 32%, the financial risks of donation. Understanding the effects of living donation on recipient outcomes was the only factor that would affect donors' decision to donate again. 40% of donors reported feeling some pressure to donate. Donors who are related to the recipient were more likely to report feeling pressure to donate. We conclude that more studies of informed consent are needed to identify factors that may compromise the validity of informed consent.

Keywords: Living donor, Informed consent, Bioethics, Consent, Ethics, Living kidney donor

INTRODUCTION

A patient with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) has limited treatment options – either a (living or deceased donor) transplant or dialysis. With transplants the survival rate and quality of life are better than with dialysis;(1–3) with living donor (LD) transplants, the long-term survival rate and graft function are better than deceased donor transplants. However, LD transplants have the disadvantage of potential risk to healthy donors. The medical risks after living kidney donation include a peri-operative mortality rate of 0.03% (4–6) and a morbidity rate, including minor complications, of less than 10%. (7)

With LD transplants there is no medical benefit to donors. Accepting the concept of living donation requires accepting the notion that the potential benefit to the recipients balances with the medical risks and the nonmedical risks and benefits to donors. When the balance between risks and benefits is sufficient, acceptance by donors is justified, on the basis of respect for their autonomy, as realized through their informed consent. (8, 9) To assert that an act of informed consent is an expression of a donor's autonomy, two key conditions must be satisfied: understanding and voluntariness. (8) In this study, we investigated whether consent to donate a kidney by the living donors at our center was voluntary and based on understanding of the risks and benefits of kidney donation.

METHODS

Study Participants

From June 1, 2002 through April 20, 2005, we performed 377 LD kidney transplants at the University of Minnesota (U of MN). Of the 377, 352 had agreed to participate in research studies post-transplant and had provided a current address. Surveys were sent to these 352 LDs to assess informed consent. If we received no response, we sent a second survey.

Of the 352 surveys sent, 262 LDs (74%) responded (mean age at donation, 43.6 ± 10.5 years; 62.2%, female; 95.4%, white). At the time of data collection, respondents were 2 to 40 months post donation. Of those 262 respondents, 68.6% were related to the recipient (28.2% sibling; 15.3% child; 9.5% spouse; 5.3% mother; 4.2% father; 6.1% other) and 31.2% were unrelated (3.4% non-directed donors).

Evaluation

At the U of MN during our study period, the potential LD evaluation (and the beginning of the informed consent process) started with the potential donor contacting our transplant center. An initial telephone screening was then done by the living donor transplant coordinator, who provided information about the donation process. If the potential LD remained interested in donating, we sent an enrollment packet which included donor education materials and detailed medical history forms to complete and mail back. After we received those forms, if we detected no contraindications to donating, we asked the potential LD to undergo blood type testing; if the blood type was compatible with the intended recipient, we next asked the potential LD to undergo histocompatibility testing. An exception to this process occurred when a potential LD came forward for the first time at the intended recipient's initial clinic visit; for those situations, we did the initial medical screening, provision of information, and blood type and histocompatibility testing at the same time as the intended recipient's visit.

Potential LDs who were histocompatible with their intended recipient underwent a complete medical evaluation. For those wishing to be evaluated at our center, we scheduled an appointment and mailed additional informational material (including a DVD outlining the surgical risks, potential long-term risks, and the expected hospital stay and recovery period). Our center's evaluation, done over an entire day, included an appointment with a transplant surgeon, a nephrologist, a transplant social worker, and a transplant coordinator. Potential LDs who had a history of psychiatric illness or substance abuse or presented concerns to the transplant professionals were evaluated by a health psychologist or a neuropsychologist. All non-directed donors were evaluated by a neuropsychologist who evaluated their mental health and cognitive function. Family members, such as spouses and significant others, may have joined potential LDs during their evaluation. At their individual appointments, we again discussed the short- and long-term risks of the donation.

Many potential LDs living long distances from our center preferred to have their full evaluation at a local center. For them, we mailed informational material and a DVD describing the risks of donation. Any questions they asked us were addressed over the phone.

Survey

To our knowledge there are no survey instruments designed to evaluate informed consent among LDs. Therefore we designed a survey to capture LDs understanding and voluntariness, including questions to ascertain (1) the adequacy of their understanding of the short- and long-term consequences of donation and (2) the level of voluntariness of their decision to donate. We formulated our 22-item survey question after reviewing the pertinent literature and interviewing transplant social workers, nurses, and physicians who work with our LDs. We first administered our survey to transplant professionals at the U of MN to evaluate the questions' understandability, and subsequently altered our survey accordingly.

To assess understanding we asked our LDs to indicate whether, at the time of their surgery, they understood (Agree, Disagree, Unsure) 6 different aspects of the donation process: donor screening process (3 questions), short-term medical risks (3 questions), long-term medical risks (4 questions), financial risks (2 questions), psychological risks (2 questions), and effects of donation on recipient outcomes (2 questions).

To evaluate voluntariness, we asked how much pressure our LDs felt to donate (1= the most pressure to 5= the least pressure). We considered anything other than a 5 to be an indication of some pressure. In a separate question we asked our LDs to identify why they decided to donate by ranking (1= the most important to 3= the least important) the following 3 possible reasons for donation: “My family expected me to donate”; “I wanted to help my recipient”; and “I wanted to give meaning to my life.”

Finally, we asked our LDs whether they would have agreed to donate a kidney if they knew then (at the time of their surgery) what they know now (at the time of the survey).

The study design and human subject enrollment protocol were reviewed and approved by the U of MN institutional review board.

Analysis

In our analysis of our LDs' understanding, we tabulated the distribution of responses to the questions in each domain of the donation process (donor screening process, short-term medical risks, long-term medical risks, financial risks, psychological risks, and effects of donation on recipient outcomes). We herein report descriptive statistics by domain, including the percent of our LDs who agreed that they understood all items. We also calculated Cronbach's alpha (cα) to assess the internal consistency of responses within each domain responses with the cα value increasing toward 1 when the correlation among items increased.

In the analysis of our LDs' voluntariness, specifically their reported feelings of any pressure, we herein report descriptive statistics. To assess strength of the association between LDs' feelings of pressure to donate and each reason for donating, we used Kendall tau c rank correlation coefficient. The value of the Kendall tau c lies between −1 and +1, with increasing values implying increasing agreement (toward +1) or disagreement (toward −1) between the rankings. The value of zero indicates negative association.

Finally, we also examined the association between LDs' reported degree of understanding with feeling of pressure to donate and feeling of pressure to donate with the donor's ordinal assessment of likeliness to donate (Yes, Unsure, No).

RESULTS

Understanding

Of our 262 respondents, 97% answered all questions assessing understanding; each question had a response rate of 99%. For each of the domains of the donation process studied, we herein report the percent who responded “Agree” to all questions assessing the specified domain (among the 97% who answered all questions).

Referring to the time of their donation, 98% answered that they understood the effects of donation on recipient outcomes (cα = 0.53); 96%, the screening process (cα = 0.62); and 92%, the short-term medical risks of donation (cα = 0.81).

In contrast, 69% answered that they understood the psychological risks of donation (cα = 0.72); 52%, the possible long-term medical risks of donation (73%, chronic pain; 59%, hypertension; 61%, proteinuria; and 92% the risk from having just one kidney) (cα = 0.77); and 32%, the financial risks of donation (cα = 0.38).

Voluntariness

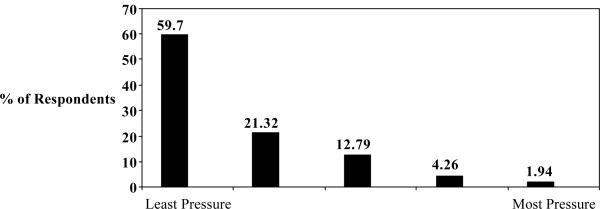

Of our 262 respondents, 40.3% answered that they felt some pressure to donate, which we defined as pressure rank < 5 (rank 1 [most pressure], 1.94%; rank 2, 4.26%; rank 3, 12.79%; and rank 4, 21.32%). See Figure 1. Reasons why respondents decided to donate were ranked (1= the most important to 3= the least important) for the following 3 possible reasons for donation: “My family expected me to donate”; “I wanted to help my recipient”; and “I wanted to give meaning to my life.”

Figure 1.

Pressure to Donate

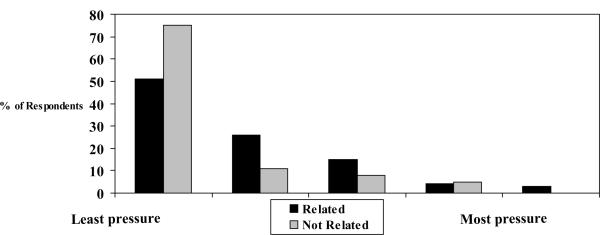

We used ordinal variables to assess their responses: rank 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 vs. reason for donation rank 1, 2, and 3. We found a positive association between the response “My family expected me to donate” and degree of pressure (Kendall tau c = 0.185, p = .0010); a negative association between the response ”I wanted to help my recipient” and degree of pressure (Kendall tau c = −0.172, p=.0033); and no association between the response ”I wanted to give meaning to my life” and degree of pressure (Kendall tau c = −0.021, p =.70). The association between being related to the recipient and the degree of pressure is depicted in Figure 2. LDs who rated family expectations as their first or second most important reason to donate were more likely to report feeling pressure (OR= 2.1; 95% CI = 1.0 to 4.4, p = 0.040). LDs related to the recipient were more likely to report feeling pressure, even after we adjusted for their rank of donating due to family expectations (OR = 2.6, 95% CI = 1.4 to 4.8, p=0.002).

Figure 2.

Pressure by Relatedness to Recipient

Finally, 94% of our LDs would donate again. The more the LD reported understanding of the impact of donation on the recipient (i.e., that the recipient would have a better outcome and a shorter wait), the more likely the LD would be to donate again (p=0.04). But we found that understanding (or lack thereof) of other tested domains of organ donation outcomes did not correlate with willingness to donate again. We found a negative association between feeling pressure to donate the first time and the willingness to donate again (Kendall tau c = −0.21, p=0.0005); note that 98% of our respondents answered both of those questions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Willingness to Donate Again by Initial Degree of Pressure

| Willingness Donate Again | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | Unsure | No | N | |

| Highest Pressure ↑ Lowest Pressure |

60% | 20% | 20% | 5 |

| 82% | 18% | 0% | 11 | |

| 88% | 12% | 0% | 33 | |

| 98% | 2% | 0% | 55 | |

| 98% | 2% | 0% | 152 | |

DISCUSSION

Informed consent means that an individual makes an autonomous choice about whether or not to participate in research or to undergo medical treatment. Truly informed consent should be based on a substantial understanding of the consequences (positive and negative) of a decision and should be made voluntarily, without undue pressure from any source (10–12) To date, no studies that we are aware of have assessed the degree of voluntariness of LDs. In addition, very few empirical studies have assessed the level of understanding of LDs. The few studies that have attempted to assess control and decision making among LDs were limited in scope (usually by including a few questions as part of a larger survey) and reached conclusions that were muddled or imprecise. Ours is, to the best of our knowledge, the first study of informed consent among LDs.

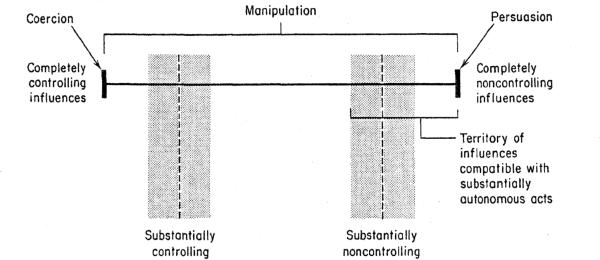

Voluntariness is a fundamental condition of an autonomous choice and therefore of informed consent. Influences that affect the voluntary nature of informed consent can be categorized into 3 forms: (1) persuasion, (2) manipulation, and (3) coercion (Figure 3) (8). Persuasion is influence through appeal to reason. (13, 14) Coercion is influence in which individuals are caused to act in ways that are against their wishes, under threat of harm (15–17). Manipulation lies between persuasion and coercion in the continuum of voluntariness; it is inherently subjective, as it is relative to an individual's response to the particular influence. In some cases, influence can be minimally manipulative (residing close to an experience of persuasion); in other cases, influence can be substantially manipulative, though still without actual threat of harm (residing close to the experience of coercion). (8)

Figure 3.

Continuum of Control

We chose to study “pressure” because it is a commonly understood term that captures the perception of feeling substantially manipulated or coerced – both of which may result in non-autonomous informed consent. We did not define pressure in our survey, because we wanted to capture LDs' own perceptions of feeling pressure. In addition, we did not try to discover the source of pressure in this initial survey. However, we recognize that identifying the source of pressure in future studies is important for designing interventions.

In our study, 40% of our respondents reported feeling some pressure to donate. We were surprised by this finding because our LDs are given opportunities to change their decision with their reason for not donating remaining confidential. Our LDs who donated to family members were most likely to feel pressure. This finding calls into question the long-held belief of the medical community that, because donating to family members (rather than to, say, a stranger) is a more conventionally understandable decision, it necessarily leads to more acceptable informed consent. In fact, non-directed donors undergo much closer scrutiny of their reasons for donation than do LDs who donate to family members. Donating to a family member may indeed place potential LDs at increased risk for giving ethically unacceptable consent; if this finding holds true in future studies, our approach to potential LDs donating to family members may need to change.

To gain better insight into what LDs understand at donation, we asked our study group questions about 6 different aspects (donor screening process, short-term medical risks, long-term medical risks, financial risks, psychological risks, and effects of donation on recipient outcomes) of the donation process. Our center routinely discusses these aspects of donation with our potential LDs; most transplant professionals agree that these are essential to potential LDs to be informed about donation. Of the aspects we studied, the impact of donation on the recipient garnered the highest rate of understanding among our survey respondents, even more than the impact of donation on themselves. The only aspect that correlated with the decision to donate again was the impact of donation on the recipient. No other item correlated (positively or negatively) with the donation decision. This finding seems to suggest that the decision of LDs to donate is based most strongly on their motivation to help the recipient (moral reasoning) as it has been previously reported (18), rather than on their understanding of the risks vs. benefits of donation. It is worthwhile noting that prior studies have shown that non-donors do not follow the moral reasoning decision-making process which often results in the decision to donate as soon as one hears of the recipient's need. Rather, a non-donor's decision is a stepwise process where small steps lead to the final decision not to donate. (18)(19)

We know of no prospective study on how much potential LDs understand about the risks and benefits of donation at the time of informed consent. However some authors contend that moral reasoning prevents potential LDs from considering alternative decisions, including not donating at all.(19) Indeed, it did not matter to our LDs that they did not understand some possible risks of donation; they would donate again. Therefore, the process for LDs is perhaps less accurately described as waiting to be informed and then deciding whether or not to donate (as we have long believed to be the case) but rather using the presented information to reaffirm and support their decision, while seeking reassurance about the limited risks involved.

Our study showed that LDs understood the effects of donation on recipient outcomes, the screening process, and the short-term medical risks of donation. The domains donors understood less well– the psychological, long term medical, and financial risks of donation – are also not well understood by the medical community. Our LDs' lack of understanding of those domains may be in response to uncertainty about the facts as presented by clinicians.

Our findings that our LDs understood the risks of donation but did not consider that information in their decision to donate may indicate that potential LDs are not well-positioned to act in ways to serve their own self-interests. Our data suggests that the traditional model of autonomy practiced through informed consent may not fit or serve LDs in part because they are acting to serve someone else's interest and not their own. Perhaps LDs do take on the medical risks of donation for tangible and/or intangible nonmedical benefits and thus act, at least in part, in their own self-interest. Our study showed that LDs can be informed but they need to be more fully informed about the long-term consequences of donation. .

Several important considerations must be taken into account in interpreting our data. First, no validated instrument exists to study informed consent in this population; therefore, the survey instrument used in our initial study continues to evolve. Second, this was a single-center study of kidney LDs at an institution where more than 90% of LDs are white and speak English; our findings may not be generalizable to other institutions and ethnicities. Third, this was a retrospective study and thus may be biased by the actual effects of donation on LDs' or their recipient's health or quality of life or by the LDs' recall abilities. Finally, our findings may not apply to other living organ transplants such as liver and lung transplants; those potential recipients are often significantly sicker, likely affecting LDs' process of giving informed consent.

Despite these considerations, we believe that this initial study of informed consent among LDs makes clear the importance of gaining a better understanding of informed consent, especially in such a unique population that will accept risks to benefit others. We need to know whether LDs are indeed providing autonomous consent, identify risk factors for inadequate consent, and design corrective measures for those risk factors. Such an effort is currently under way in an ongoing prospective multi-center study of informed consent among living kidney donors as part of the RELIVE (Renal and Lung Living Donor Evaluation Study) studies to provide information on the outcomes of living organ donation (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00608283). In addition, we need to have more debate about how to protect LDs, particularly regarding whether the principle of autonomy alone is adequate to serve this population.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The research described in this manuscript was not funded by a granting agency. However, this data was used to secure NIH funding for research that is now ongoing (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00608283). In addition, Dr. Valapour is supported by an NIH career development grant (Grant No. K23HL06210 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute) that supported her effort for this project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Evans RW, Manninen DL, Garrison LP, Jr, Hart LG, Blagg CR, Gutman RA, Hull AR, Lowrie EG. The quality of life of patients with end-stage renal disease. N Engl J Med. 1985 Feb 28;312(9):553–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198502283120905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schnuelle P, Lorenz D, Trede M, Van Der Woude FJ. Impact of renal cadaveric transplantation on survival in end-stage renal failure: Evidence for reduced mortality risk compared with hemodialysis during long-term follow-up. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998 Nov;9(11):2135–41. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V9112135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LYC, Held PJ, Port FK. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 1999 December 2;341(23):1725–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912023412303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bay WH, Hebert LA. The living donor in kidney transplantation. Ann Intern Med. 1987 May;106(5):719–27. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-106-5-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Najarian JS, Chavers BM, McHugh LE, Matas AJ. 20 years or more of follow-up of living kidney donors. Lancet. 1992 Oct 3;340(8823):807–10. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92683-7. see comment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matas AJ, Bartlett ST, Leichtman AB, Delmonico FL. Morbidity and mortality after living kidney donation, 1999–2001: Survey of united states transplant centers. Am J Transplant. 2003 Jul;3(7):830–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson EM, Remucal MJ, Gillingham KJ, Dahms RA, Najarian JS, Matas AJ. Complications and risks of living donor nephrectomy. Transplantation. 1997 Oct 27;64(8):1124–8. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199710270-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faden RR, BT . A History and Theory of Informed Consent. Oxford University Press; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz J. The Silent World of Doctor and Patient. Free Press, Macmillan; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ingelfinger FJ. Informed (but uneducated) consent. N Engl J Med. 1972 Aug 31;287(9):465–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197208312870912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Somerville MA. Law Reform Commission of Canada, editor. Consent to Medical Care. Protection of life series : study paper (Law Reform Commission of Canada) ; 2 Study paper (Law Reform Commission of Canada) ed. Copyright: Minister Supply and Services Canada; Ottawa, Ontario: 1979. The duty to inform the patient or research subject for the purpose of obtaining “informed” consent; pp. 12–29. 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stansfield MP. Malpractice: Toward a viable disclosure standard for informed consent. Oklahoma Law Rev. 1979 Fall;32(4):868–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benn SI. Freedom and persuasion*. Australasian Journal of Philosophy. 1967;45(3):259–75. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petty RE. The Role of Cognitive Responses in Attitude Change Processes. In: Petty RE, Ostrom TM, Brock TC, editors. Cognitive Responses in Persuasion. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1981. pp. 135–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gert B. Coercion and Freedom. In: Pennock JR, Chapman JW, editors. Coercion. Atherton Inc.; Chicago: Aldine: 1972. pp. 30–48. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nozick R. Coercion. In: Morgenbesser S, Suppes P, White M, editors. Philosophy, Science, and Method: Essays in Honor of Ernest Nagel. St. Martin's Press; New York: 1969. pp. 440–72. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bayles MD. A Concept of Coercion. In: Pennock JR, Chapman JW, editors. Coercion. Atherton Inc.; Chicago: Aldine: 1972. pp. 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simmons RG, Marine SK, Simmons RL. Gift of Life: The Effect of Organ Transplantation on Individual, Family, and Societal Dynamics. Second ed. Transaction Publishers; New Brunswick, New Jersey: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janis IL, Mann L. Decision making: a psychological analysis of conflict, choice, and committment. Free Press; New York: 1977. New York: Free Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]