Abstract

Older adults are commonly accompanied to routine physician visits, primarily by adult children and spouses. This is the first review of studies investigating the dynamics and consequences of patient accompaniment. Two types of evidence were examined: (1) observational studies of audio and/or videotaped medical visits, and (2) surveys of patients, families, or health care providers that ascertained experiences, expectations, and preferences for family companion presence and behaviors in routine medical visits. Meta-analytic techniques were used to summarize the evidence describing attributes of unaccompanied and accompanied patients and their companions, medical visit processes, and patient outcomes. The weighted mean rate of patient accompaniment to routine adult medical visits was 37.6% in 13 contributing studies. Accompanied patients were significantly older and more likely to be female, less educated, and in worse physical and mental health than unaccompanied patients. Companions were on average 63 years of age, predominantly female (79.4%), and spouses (54.7%) or adult children (32.2%) of patients. Accompanied patient visits were significantly longer, but verbal contribution to medical dialogue was comparable when accompanied patients and their family companion were compared with unaccompanied patients. When a companion was present, health care providers engaged in more biomedical information giving. Given the diversity of outcomes, pooled estimates could not be calculated: of 5 contributing studies 0 were unfavorable, 3 inconclusive, and 2 favorable for accompanied relative to unaccompanied patients. Study findings suggest potential practical benefits from more systematic recognition and integration of companions in health care delivery processes. We propose a conceptual framework to relate family companion presence and behaviors during physician visits to the quality of interpersonal health care processes, patient self management and health care.

Keywords: Family caregiver, primary health care, physician office, care coordination, patient-provider communication

INTRODUCTION

There is little dispute that families are relevant to health and health care. Family involvement has been articulated as one of six dimensions of patient-centered care (Gerteis, Edgman-Levitan, & Daley, 1993), and a central tenant of chronic care processes (Institute). Numerous studies empirically demonstrate the relevance of family to patients’ engagement in medical decision-making (Clayman, Roter, Wissow, & Bandeen-Roche, 2005), satisfaction with physician care (Wolff & Roter, 2008), treatment adherence (DiMatteo, 2004), quality of health care processes (Glynn, Cohen, Dixon, & Niv, 2006; Vickrey, Mittman, Connor, Pearson, Della Penna, Ganiats et al., 2006), physical and mental health (Seeman, 2000), and mortality (Christakis & Allison, 2006). Yet despite a broad appreciation that families matter, specific knowledge regarding which actions and behaviors undertaken by family members are most helpful, or efficacious in improving health, is limited. The complexity of family attributes and dynamics and capacity to both benefit and exacerbate health and health care (DiMatteo, 2004; Seeman, 2000), complicate measurement and intervention efforts. A better understanding of the pathways by which families and friends exert their influence within routine medical visits could inform efforts to improve the patient-physician partnership as well as chronic care innovations, such as the patient-centered medical home.

Building on the conceptual underpinnings of high quality chronic care, innovative approaches have been developed to equip patients with the tools, skills, and information to self-manage health care (IOM, 2008). However these approaches may be less applicable to older, less literate, and chronically ill patients, who are less assertive and less interested in shared decision-making, (Arora & McHorney, 2000; Ende, Kazis, Ash, & Moskowitz, 1989; Levinson, Kao, Kuby, & Thisted, 2005) and for whom primary care visit time constraints are especially problematic (Fiscella & Epstein, 2008). That older, less literate, and sicker patients are most likely to be accompanied to routine physician visits (Wolff & Roter, 2008), raises the possibility that optimizing family involvement in routine medical visits may present a viable strategy for improving chronic care processes for this challenging patient population.

Conceptual Orientation

The term “family” is used throughout this manuscript given evidence that it is most often spouses and adult children who accompany patients to health care encounters (Wolff & Roter, 2008), however the term is used broadly, and meant to encompass friends who may also be present and involved in physician visits. The importance and implications of family as providers of assistance in the home and community (e.g., as “family caregivers”) and in negotiating health system logistics, has been established (IOM, 2008). In this paper, we focus more narrowly on the presence and behaviors of family within older adults’ routine face-to-face medical encounters. The salience of family involvement in medical visit dialogue is considered conceptually and empirically in relation to interpersonal processes, patient self management and quality of care.

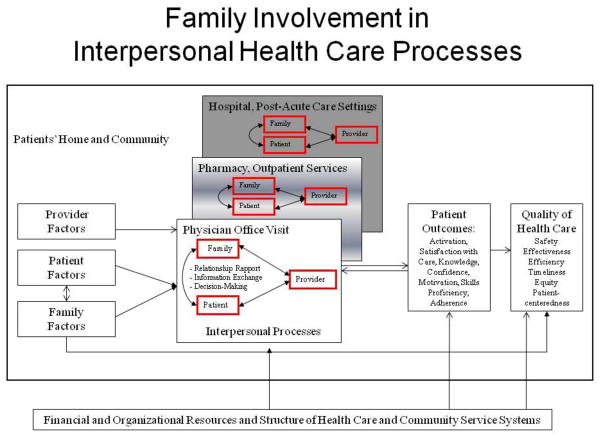

We have developed a framework that depicts how patients, families, and professional caregivers interact and the pathways by which family companions influence interpersonal processes and outcomes of medical encounters (Figure). The context within which health care is delivered is shaped by patients’ homes, communities, and local health care and community service systems. Patient, family, and provider attributes are brought to bear on interpersonal processes during physician office visits, shown at the center of the model. Coordination of care is shown in our model as emanating from triadic patient-family-provider exchanges that span time and place. The replication of linked triadic dialogue is depicted across health care settings that include but are not limited to: physician office visits, pharmacy and outpatient services, and hospital and other post-acute care settings. Although the model depicts patient outcomes and quality of care as emanating from physician office visit processes, we believe that the collective replication and linkages of triadic communication processes across a range of health care settings, and with a variety of health care professionals has a bearing in regard to whether quality outcomes are achieved.

Figure.

Family Involvement in Interpersonal Health Care Process

To further elaborate on our framework, three defined, albeit interrelated, aspects of interpersonal processes (1) relationship rapport, (2) information exchange, and (3) medical decision-making, are described in relation to accompanied patients’ medical visits. Relationship rapport refers to trust, empathy, respect, genuineness, and mutuality to support the establishment of a productive alliance among all parties (patient, family companion, provider). In general, physician communication patterns that are less dominant and more participatory and empathetic engender positive rapport (Schmid Mast, Hall, & Roter, 2008;R. L. Street, Jr., Makoul, Arora, & Epstein, 2009). However, physicians employ more paternalistic, biomedical communication with the types of patients who tend to be accompanied --- older, sicker, and socially disadvantaged patients (Fiscella & Epstein, 2008; Hall, Epstein, DeCiantis, & McNeil, 1993; Hall, Horgan, Stein, & Roter, 2002; Roter, Stewart, Putnam, Lipkin, Stiles, & Inui, 1997).

Information exchange, the giving and receiving of knowledge about patients’ health, symptoms, values, preferences, beliefs, and treatments, is a central function of health care encounters (Makoul, 2001). Providers require information from patients for accurate diagnosis and relevant treatment. Patients require information from providers regarding the nature and expected course of their condition as well as treatment options, benefits, side effects, and uncertainty. Information exchange is especially challenging for medically complex patients with more extensive physical symptoms and psychosocial stresses; the types of patients who tend to be accompanied. Given constraints on physician time and limited flexibility in visit length (Chen, Farwell, & Jha, 2009; Tai-Seale, McGuire, & Zhang, 2007), there is less opportunity for medically complex patients to adequately disclose and discuss their health information. Older and less-literate patients have been shown to prefer physician-directed care (Arora & McHorney, 2000; Ende et al., 1989; Levinson et al., 2005), and to ask fewer questions, express fewer concerns, and to be less apt to seek clarification of information (Arora & McHorney, 2000; Eggly, Penner, Greene, Harper, Ruckdeschel, & Albrecht, 2006). These communication patterns may suggest to physicians that patients are uninterested in visit dialogue, or unwilling to engage in discussion.

Although patients vary in their preferences for sharing health care decision-making responsibilities with health care providers (Ende et al., 1989; Levinson et al., 2005) the “shared” medical decision-making paradigm has been embraced in recent years as particularly relevant to chronic care, where patient responsibilities and actions largely determine success (Murray, Charles, & Gafni, 2006). At its most basic level, the paradigm implies that clinical issues and options are defined and explained in an understandable manner and in sufficient detail (relative merits, drawbacks, and uncertainties) so that the patient may assess them within the context of their own preferences and values (Charles, Gafni, & Whelan, 1999; Murray et al., 2006). While beginning to change (Edwards & Elwyn, 2009), much of the decision-making literature has focused on a single treatment in light of a well-defined serious or life threatening illness (Charles et al., 1999). The chronic care decision-making paradigm is in many ways less straightforward due to the greater number of potential issues for discussion, the fact that decision-making occurs iteratively across time and in consultation with a variety of stakeholders (such as family), and ambiguity regarding which decisions are most urgent (Murray et al., 2006). Given limited time and competing issues, negotiation to establish a visit agenda may be an important part of the chronic care decision making process.

It is our hypothesis that family companions exert a largely positive influence on medical visit dialogue by improving patient-provider relationship rapport, facilitating information exchange, and engaging patients in medical decision-making. We further surmise that family companions’ involvement extends beyond the medical encounter to health care management at home and in the community. We believe that family involvement in interpersonal health care processes has a bearing on the quality of patients’ health care, as defined by indices specified by the IOM. For example, family companions’ facilitate information transfer and coherent service use across time and health care settings, such as among patients discharged from the hospital to home (efficiency). Families motivate patients to adhere to treatment regimens on a daily basis (effectiveness), initiate contact with health professionals to report on emerging conditions or symptom exacerbation (timeliness; safety), and advocate on behalf of patients for services, benefits, and provider attentiveness to patients’ preferences and needs (patient centeredness; equity). The extent to which families are acknowledged and supported by providers may also be influential to their own well being; it has been suggested that most patients would amend intended treatment goals to encompass the experiences and perspectives of their families (Berwick, 2009).

While the broad and reciprocal pathways by which family involvement in interpersonal health care processes influence a wide range of health and health care outcomes, the focus of this paper is limited to family companions and their behaviors during office visits. Studies describing family companions’ contributions to medical visit dialogue are relatively few in number and have not been systematically reviewed to date. To this end, we review empirical evidence from the published literature to describe what is currently known regarding whether and how the presence of a family companion has a bearing on interpersonal processes within the context of routine medical encounters, as well as patient outcomes and quality of health care. Our goal is to construct a unifying framework for considering this body of work, to evaluate and summarize methods and findings from relevant studies, and to consider implications of study findings with regard to future directions in chronic care endeavors.

DATA SOURCES AND METHODS

Search Strategies and Inclusion Criteria

To be included in this review, studies had to: (1) have been published in an English language journal, (2) describe medical visit interactions between adult patients and health care professionals, and (3) present quantitative information regarding patient accompaniment as it relates to any of the following: patient or family companion attributes, visit structure, communication processes, and/or outcomes of care. Studies restricted to pediatric patients, to hospitalized or terminally ill patients, patients presenting with urgent care needs in the emergency room, or describing end-of-life care, genetic counseling, or specialty mental health visits were excluded. We included studies of routine medical visits between adult patients of all ages and diseases and health care professionals that occurred in office and outpatient practice settings. Although our primary interest was interactions between older adults and their usual care physician, we included studies that described routine medical visits by accompanied patients with physicians-in-training, nurses, or physicians’ assistants. Observational studies that investigated accompanied patients’ communication using audio- and/or video-taped dialogue from medical encounters were included, as well as surveys of patients, families, and/or health care professionals that ascertained their experiences, expectations, and preferences regarding the behaviors of accompanying family companions to routine medical visits.

Electronic databases PsychInfo and PubMed were searched from 1949 through July 2009. The terms “accompaniment”, “accompany”, “companion”, “family member” were combined with mesh terms “physician’s offices”, “ambulatory care”, “office visits”, “physician-patient relations” and text words “medical visit”, “physician visit”, “doctor-patient interactions”. A total of 300 abstracts were identified and reviewed in full; 8 met our criteria for inclusion. Review of citations from these 8 articles yielded an additional 4 studies. Citation tracking for these 12 papers using the Scopus search engine yielded 4 studies. Finally, authors of papers published within the last 5 years were contacted to identify additional work that had yet to appear in the published literature. In all, 17 studies were identified: 10 observational studies of audio or videotaped encounters that studied medical visits among accompanied patients (combined n=1,098 patients) and 7 surveys of patients, families, and/or physicians (combined n=15,240 patients; see Appendix and Table 1).

Table 1.

Contributing Studies Reporting on Adult Patient Accompaniment to Routine Medical Visits

| Author | Year | Country | Patient (n) | Age | Provider Sample | Provider Type/Setting | Visit Type | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observational (n=10; 1,098 patients) | ||||||||

| Beisecker | 1989 | US | 21 | 60+ | 7 Physicians; 1 Hospital | Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation | Not specified | Variable |

| Clayman | 2005 | US | 93 | 65+ | 37 Physicians; 3 Hospitals | Primary Care | Follow-up | Variable |

| Greene | 1994 | US | 30 | 60+ | 9 Physicians; 1 Hospital | Primary Care | New | Variable |

| Ishikawa | 2005 | Japan | 145 | 65+ | 9 Physicians; 1 Site | Primary Care/Geriatrics | Follow-up | Variable |

| Shields | 2005 | US | 30 | 65+ | Not reported; 2 Sites | Primary Care/Geriatrics | Follow-up | Variable |

| Schmidt | 2009 | US | 23 | 65+ | 20 Physicians | Primary Care | Follow-up | Alzheimers |

| Labreque | 1991 | US | 473 | All | 5 Physicians; 1 Site | Oncology | Follow-up | Oncology |

| Street | 2008 | US | 132 | All | 15 Physicians;2 PAs; 1 Hospital | Oncology | 70% new | Lung cancer |

| Jansen | 2009 | NE | 100 | 65+ | 37 Nurses; 10 Hospitals | Oncology | New | Oncology |

| Oguchi | 2010 | AU | 51 | All | 13 Nurses; 2 Sites | Oncology | New | Oncology |

| Patient Survey/Interview (n=7; 15,240 patients) | ||||||||

| Botelho | 1996 | US | 457 | 18+ | 30 Physicians; 1 Site | Primary Care | Follow-up | Variable |

| Brown | 1998 | Canada | 800 | All | 8 Physicians | Primary Care | Follow-up | Variable |

| Glasser | 2001 | US | 185 | 60+ | Not reported; 4 Sites | Primary Care/Geriatrics | Follow-up | Variable |

| Prohaska | 1996 | US | 129 | 60+ | Not reported; 2 Sites | Primary Care | Follow-up | Variable |

| Schilling | 2002 | US | 1294 | 18+ | 57 Physicians; 1 Hospital | Primary Care | Follow-up | Variable |

| Wolff | 2008 | US | 12018 | 65+ | “Usual Source of Care” | Population Survey | Routine Visits | Variable |

| Silliman | 1996 | US | 357 | 70+ | Not reported; 3 Sites | Primary Care | "Usual" | Diabetes |

Article Coding, Effect Size Calculation, and Statistical Analyses

Meta-analytic techniques were used to summarize available evidence regarding attributes of accompanied and unaccompanied patients, medical visit processes, and outcomes. Data from included studies were extracted by the first-author and reviewed by the second author. Disagreements about coding decisions were resolved by discussion between the two review authors. Information regarding year of publication, type of data (observational versus patient report), study sample (sample size, study setting, provider type, patient population, age criteria, country of study), patient attributes (accompaniment status, age, gender, race, education, health), companion attributes (age, gender, relationship to patient), communication process measures (if applicable), and patient outcomes (when reported) was recorded for each study using data extraction sheets that were developed for this study. We relied on established conceptual groupings of communication process measures, using the following categories: social conversation, positive talk, negative talk, biomedical and psychosocial information giving, and information-seeking (Hall, Roter, & Katz, 1988; Roter & Hall, 1988). Patient outcomes were defined broadly to include measures relating to patient self management: activation, satisfaction with care, knowledge, confidence, motivation, skills, proficiency, and adherence.

Quantitative information regarding accompanied and unaccompanied patient attributes and accompanied and unaccompanied visit communication structure, processes, and outcomes was extracted from each study. Estimates from studies were combined, and, when possible, the magnitude of group differences were calculated with meta-analytic techniques by computing an effect size (r; (Rosenthal, 1991). Briefly, the average standard normal deviate (Z) and effect size (r) were extracted or computed from information presented within each study; dichotomous group differences were transformed to an effect size (Chinn, 2000). When these statistics could not be calculated due to insufficient information but a conventional p-value was reported in the study, the associated one-tailed z was entered (e.g., if p-value was stated to be <0.05, we took z=1.645). When studies reported only that estimate differences were “not significant,” z was designated as 0. When a single study contributed more than one result within a particular process or outcome category, the average was entered as that study’s contribution to the summary result within the category. The r for each estimate was transformed to its associated Fisher zr and pooled unweighted and weighted effect sizes (r) were calculated. Fixed effects confidence intervals were estimated, (Rosenthal & DiMatteo, 2001) and combined tests of statistical significance were calculated using the Stouffer method. Given the small number of studies contributing information on communication processes, we were unable to compute pooled effect sizes and estimates for all comparisons for unaccompanied versus accompanied medical visits. Throughout, a positive r indicates that the specified communication process occurred more frequently during accompanied patient medical visits relative to unaccompanied patient medical visits.

There was tremendous heterogeneity in regard to the nature and measurement of patient outcomes. Therefore, information regarding contributing studies’ sample size, method of data ascertainment, nature of patient outcomes, and analytic approach were summarized. Average and maximum effect size and associated confidence intervals were determined for each estimate; the text describes average effect sizes. Three studies reported information regarding patient outcomes by virtue of companions’ verbal activity and we extracted information from these studies using a parallel process that presents effect sizes from individual studies rather than pooled estimates. In regard to patient outcomes, a positive r indicates that study outcomes were favorable for accompanied relative to unaccompanied patient, or, in regard to accompanied patients, that outcomes were favorable for patients whose companions were more, versus less verbally active.

Lastly, we augmented information from observational studies with findings from 5 studies that surveyed patient, family, and/or physicians regarding the roles they perceived as being assumed by patients’ family companion during medical encounters. Responses regarding companions’ roles and/or reason for being present were grouped using the previously mentioned categorization scheme. When a single study provided more than one relevant response from a given party within a given categorization domain, the most frequently endorsed estimate was used in our calculations. This approach was used to avoid conceptual redundancy, and is conservative in that it underestimates responses endorsing the roles assumed by companions by party (patient, companion, physician) within a given category. For each domain, the average and range of responses was reported by party.

RESULTS

How frequently are adult patients accompanied to physician office visits?

The mean rate of accompaniment to routine adult physician visits was 46.1% in 13 studies that reported on the presence of a family companion (top panel of Table 2). The proportion of patients who were accompanied to medical visits was lower in studies that relied on patient surveys or interviews (37.3%) as compared with observational studies (56.3%; of 6 contributing studies, 4 were oncology patient populations). The mean, weighted mean, and median rate of patient accompaniment was comparable across studies that relied on patient surveys or interviews (37.3%; 37.4%; 38.5% respectively) but was more variable for observational studies (56.3%; 41.0%; 60.4%), reflecting fewer studies and smaller and more diverse study samples. The overall weighted mean and median rate of patient accompaniment were similar: 37.6% and 38.9%, respectively.

Table 2.

Summary of Contributing Studies and Patient, and Companion Characteristics (n=17 Studies)

| Variable (number of studies reporting) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Median (Range) | Mean (SD) | Weighted Mean |

| Number of Patients | |||

| Observational (n=10) | 72 (21–473) | 109.8 | |

| Survey (n=7) | 457 (129–12018) | 2177.1 | |

| Overall (n=17) | 132 (21–12018) | 961.1 | |

| Rates of Patient Accompaniment (%) 1 | |||

| Observational (n=6) | 60.4 (20.9–86.2) | 56.3 (24.2) | 41.0% |

| Survey (n=7) | 38.5 (28.9–50.5) | 37.3 (6.9) | 37.4% |

| Overall (n=13) | 38.9 (20.9–86.2) | 46.1 (17.8) | 37.6% |

| Mean (Range) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Profile | Unaccompanied | Accompanied | Difference | P-value 2 |

| Mean Age (years; n=12) | 66.6 (41.7–74.8) | 70.1 (40.0–83.7) | 3.5 | <0.01 |

| Caucasian (%; n=5) | 72.9 (64.4–82.4) | 70.1 (58.9–83.0) | −2.8 | 0.12 |

| Female Gender (%; n=10) | 53.0 (11.8–73.0) | 58.6 (38.7–76.1) | 5.6 | <0.01 |

| Education | ||||

| High school or more (%; n=8) | 59.7 (11.9–83.5) | 42.8 (9.8–67.3) | −16.9 | |

| All studies reporting on education (n=9)3 | <0.01 | |||

| Physical Health | ||||

| Excellent or Very Good Self Rated Health (%; n=4) | 41.4 (27.4–59.4) | 28.2 (12.5–43.1) | −13.3 | |

| All studies reporting on physical health (n=8)3 | <0.01 | |||

| Mental Health | ||||

| Absence of psychiatric condition/symptoms (%; n=2) | 86.9 (85.0–88.7) | 73.0 (62.5–83.5) | −13.9 | |

| All studies reporting on mental health (n=5)3 | <0.01 | |||

| Family Companion Profile | Median (Range) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (years; n=5) | 62 (58–68) | 63.0 (4.0) |

| Female (%; n=7) | 78.0 (63.0–93.0) | 79.4 (10.6) |

| Relationship to patient (%) | ||

| Spouse (n=12) | 54.0 (38.5–71.0) | 54.7 (10.5) |

| Child (n=10) | 35.5 (10.0–53.8) | 32.2 (13.2) |

| Other (n=13) | 16.0 (0.0–45.0) | 18.7 (13.9) |

Studies of accompanied patients only (Clayman; Schmidt) or that matched (Greene) or randomized (Shields) to accompaniment status are excluded from calculations.

P-values are two-tail and based on pooled estimates.

Sample used to determine estimates require consistency in measurement; may be different from sample used to determine statistical significance of group differences.

Who are accompanied patients and their family companions?

We constructed socio-demographic and health profiles of accompanied and unaccompanied patients from published studies to summarize information regarding patient characteristics (Table 2; middle panel). Accompanied patients were on average 3.5 years older, 5.6% more likely to be female, 16.9% less likely to have graduated from high school, 13.3% less likely to rate themselves as being in “excellent” or “very good” health, and were 13.9% less likely to have no psychiatric conditions (p<0.01 all contrasts). Attributes of family companions were also examined. Family companions were on average 63 years of age, female (79.4%), and spouses of patients (54.7%) or their adult children (32.2%; bottom panel of Table 2). Relatively few companions were other relatives, friends, or paid companions (18.7%).

How does accompaniment influence the duration and structure of medical visits?

In six observational studies that reported medical visit duration, accompanied patients’ visits were approximately 20% longer (r=0.19), relative to unaccompanied patient visits, a difference that was statistically significant (p<0.01; Table 3). Three studies provided information regarding patient, companion, and physician verbal activity, expressed as average proportion of visit utterances, or words spoken during the visit. Although accompanied patients were less verbally active than their unaccompanied counterparts, (r=0.16; p<0.01), no difference in verbal activity was evident when unaccompanied patients were compared with accompanied patients and their family companion together (r=0.02; p=0.73). Verbal activity of physicians was comparable in dyadic and triadic encounters, accounting for an average of 54.4% and 53.3% of visit dialogue, respectively (r=−0.02; p=0.78).

Table 3.

Summary of Visit Duration and Participant Verbal Activity from Observational Studies

| Duration of Visit | k1 | n2 | Median (Range) | Mean (SD) | Pooled Effect Size, r (95%CI) | Pooled Significance | P-Value for Heterogeneity 5 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accompanied | Accompanied | ||||||||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | Unweighted Mean r 3 | Weighted Mean r 3 | Combined Z 3 | P- Value 4 | ||||

| Length of Visit (Minutes) 6 | 6 | 883 | 20.2 (8.8, 49.1) | 25.1 (11.7, 57.4) | 24.6 (19.1) | 29.8 (21.4) | 0.13 (−0.01,0.27) | 0.19 (0.05,0.32) | 4.28 | <0.01 | 0.21 |

| Verbal Activity, by Participant (%) 6,7 | |||||||||||

| Patient | 3 | 307 | 45.9 (42.4,48.4) | 29.1 (27.7,40.4) | 45.5 (3.0) | 32.4 (6.9) | −0.14 (−0.24,−0.04) | −0.16 (−0.26,−0.06) | −2.45 | <0.01 | 0.92 |

| Patient and Companion | 3 | 307 | 45.9 (42.4,48.4) | 48.9 (48.7,57.6) | 45.5 (3.0) | 47.3 (5.0) | 0.02 (−0.06,0.09) | 0.02 (−0.06,0.10) | 0.35 | 0.73 | 0.88 |

| Physician | 3 | 307 | 54.1 (51.6,57.6) | 53.0 (48.7,58.3) | 54.4 (3.0) | 53.3 (4.8) | −0.01 (−0.10,0.08) | −0.02 (−0.11,0.07) | −0.28 | 0.78 | 0.87 |

k=number of independent study samples.

n=total sample for all contributing studies.

Positive effect in regard to visit duration indicates accompanied visits longer; in regard to verbal activity positive effect r indicates that dialogue for patient, patient and companion, and physician represent a greater proportion of visit dialogue during accompanied relative to unaccompanied visits.

P-value of Combined Z for weighted estimate. P-values are two-tail.

p<0.10 is considered evidence of substantial heterogeneity.

Contributing studies: Beisecker, Greene, Ishikawa, Jansen, Labreque, Street (visit duration); Ishikawa, Street, Shields (verbal activity).

Reflect average proportion of per-visit utterances (Ishikawa and Street) and mean words spoken (Shields).

How does accompaniment influence patient-provider communication?

Six observational studies examined medical visit communication by accompaniment status (Table 4). Effect sizes were generally small and insignificant. The only effects to achieve statistical significance indicate that physicians engaged in more biomedical information giving when a companion was present (r=0.17; p=0.01) and that patients provided less psychosocial information (r=−0.11; p=0.04), although interpretation of this effect merits caution given evidence of heterogeneity. Findings suggest that when with accompanied patients, physicians engage in less social conversation (r= −0.08; p=0.13).

Table 4.

Summary of Visit Dialogue Profile from Observational Studies Accompanied Versus Unaccompanied Medical Visit Communication

| k1 | n2 | Pooled Effect Size; r (95% CI) |

Pooled Significance |

P-Value for Heteroneity5 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median r (Range) 3 | Unweighted Mean r 3 | Weighted Mean r 3 | Combined Z 3 | P- Value 4 | ||||

| Positive Talk/Social Role Function | ||||||||

| Patient | 2 | 175 | −0.09 (−0.13,−0.04) | −0.09 (−0.70,0.61) | −0.06 (−0.69,0.62) | −0.87 | 0.38 | 0.68 |

| Patient and companion 6 | 1 | 145 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Physician | 3 | 648 | −0.05 (−0.10, 0.00) | −0.05 (−0.16,0.07) | −0.08 (−0.20,0.04) | −1.50 | 0.13 | 0.79 |

| Negative Talk | ||||||||

| Patient | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Patient and companion 6 | 2 | 277 | −0.05 (−0.16, 0.06) | −0.05 (−0.28,0.18) | −0.05 (−0.28,0.18) | −0.81 | 0.42 | 0.06 |

| Physician | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Information Giving | ||||||||

| Biomedical | ||||||||

| Patient | 3 | 205 | 0.03 (0.01, 0.20) | 0.07 (−0.19,0.33) | 0.04 (−0.22,0.30) | 0.68 | 0.50 | 0.65 |

| Patient and companion 6 | 3 | 205 | 0.03 (−0.03, 0.17) | 0.05 (−0.21,0.30) | 0.00 (−0.25,0.25) | 0.35 | 0.73 | 0.63 |

| Physician | 3 | 648 | 0.10 (0.02, 0.19) | 0.07 (−0.17,0.31) | 0.17 (−0.07,0.39) | 2.57 | 0.01 | 0.18 |

| Psychosocial | ||||||||

| Patient | 4 | 256 | −0.10 (−0.43, 0.00) | −0.16 (−0.44,0.15) | −0.11 (−0.41,0.20) | −2.09 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| Patient and companion 6 | 3 | 205 | −0.06 (−0.29, 0.02) | −0.14 (−0.56,0.35) | −0.05 (−0.50,0.43) | −0.99 | 0.32 | 0.19 |

| Physician | 2 | 175 | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.02) | −0.01 (−0.32,0.30) | 0.01 (−0.30,0.32) | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.81 |

| Information Seeking | ||||||||

| Patient | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Patient and companion 6 | 2 | 277 | 0.03 (0.00, 0.05) | 0.03 (−0.22,0.28) | 0.03 (−0.22,0.28) | 0.44 | 0.66 | 0.74 |

| Physician | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

n=total sample for contributing studies.

For each contrast, positive effect indicates communication occurred more commonly during accompanied relative to unaccompanied medical visits.

P-value of Combined Z. P-values are two-tail.

p<0.10 is considered evidence of substantial heterogeneity.

patient and companion versus patient alone.

Note: contributing studies: Greene, Ishikawa, Shields, Labreque, Oguchi, and Street.

Does being accompanied have a bearing for patient outcomes?

Five studies examined patient outcomes in relation to accompaniment status (Table 5). Given the diversity of outcomes, pooled estimates could not be calculated: of 5 contributing studies 0 were unfavorable, 3 inconclusive, and 2 favorable for accompanied relative to unaccompanied patients. The two positive effects were derived from a large national survey that adjusted for differences in patient characteristics by accompaniment status (Wolff & Roter, 2008), and for information recall, using objective ascertainment (Jansen, van Weert, Wijngaards-de Meij, van Dulmen, Heeren, & Bensing, 2009). Inconclusive effects were obtained from studies that were conducted between 1991 and 1996 that relied on patient reported outcomes.

Table 5.

Summary of Patient Outcomes and Routine Medical Visit Accompaniment

| Accompanied Versus Unaccompanied Patients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study (Year) | Outcome(s) | Study Sample | Number of Items | Type of Data | Results Adjusted | Average Effect Size (95% CI) | Largest Effect Size (95% CI) |

| Prohaska (1996) | Satisfaction, knowledge, understanding, anxiety, expectation | 129 | 6 | Patient Report | No | −0.09 (− 0.25,0.08) | −0.21 (−0.35, − 0.04) |

| Greene (1994) | Satisfaction | 30 | 1 | Patient Report | No | 0.00 (−0.35,0.35) | 0.00 (−0.35,0.35) |

| Labrecque (1991) | Satisfaction | 473 | 1 | Patient Report | Yes | 0.00 (−0.09,0.09) | 0.00 (−0.09,0.09) |

| Wolff (2008) | Satisfaction with usual provider across three domains | 12,018 | 12 | Patient Report | Yes | 0.09 (0.07,0.11) | 0.10 (0.07,0.11) |

| Jansen (2009) | Absolute information recall | 100 | 11 | Recall questionnaire, audiotaped dialogue | No | 0.31 (0.09,0.48) | 0.58 (0.42,0.70) |

| Accompanied Patients Only: Verbally Active Versus Less Active Companions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study (Year) | Outcome(s) | Study Sample | Number of Items | Type of Data | Results Adjusted | Average Effect Size (95% CI) | Largest Effect Size (95% CI) |

| Clayman (2005) | Patient decision making; coded dialogue across 5 domains | 93 | -- | Audiotaped dialogue | Yes | 0.05 (−0.16,0.25) | 0.24 (0.03,0.41) |

| Street (2008) | Patient satisfaction (single item; 10-point scale) | 84 | 1 | Patient Report | Not stated | 0.18 (−0.04,0.38) | 0.18 (−0.04,0.38) |

| Wolff (2008) | Patient satisfaction with usual provider across three domains | 3,794 | 12 | Patient Report | Yes | 0.15 (0.11,0.18) | 0.19 (0.16,0.22) |

Note: positive effect indicates that the outcome occurred more commonly during accompanied relative to unaccompanied medical visits (top panel) or among patients with more versus less verbally active companions (bottom panel).

Three studies reported verbal activity assumed by companions during the medical encounter in relation to accompanied patients’ involvement in medical decision-making (Clayman et al., 2005) and satisfaction (R. Street & Gordon, 2008; Wolff & Roter, 2008). In all three studies, companion verbal activity was favorably related to patient outcomes; only one effect was statistically significant.

What are patient, companion, and physician perspectives on accompaniment?

Studies that elicited patient, companion, and/or physician perspectives regarding family companions’ functions were used to augment observational data (Table 6). An average of 38.5% of patients (n=4 studies) endorsed the social role function of family companions in providing emotional support, encouragement, reassurance, and company. This social role function assumed by family companions was asserted by 46.3% of companions and 65.0% of physicians. Family companions were also reported to assist with a number of information giving (e.g., helping patients remember or recall information, providing information to the physician directly, or explaining physician instructions to help the patient understand) and information seeking (e.g. asking questions or helping record information) functions. Neither patients nor companions reported family companions to engage in “negative talk;” however, 15% of physicians in one contributing study stated family companions assumed a controlling or discouraging role in visits.

Table 6.

Rationale for Patient Accompaniment to Physician Visits Surveyed Patients, Companions, and Physicians (n=5 studies)*

| Respondent |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Talk/Social Role Function | Patient (n=4) | Companion (n=4) | Physician (n=1) |

| Reassurance, emotional support, company | |||

| Contributing studies | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Mean (range) | 38.5% (28.4–53.0) | 46.3% (39.6–53.0) | 65.0% |

| Negative Talk | |||

| Discouraging, controlling; discuss own symptoms | |||

| Contributing studies | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Mean (range) | 0.0% | 0.0% | 15.0% |

| Information Giving | |||

| Help patient remember - e.g., recall, explain symptoms | |||

| Contributing studies | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Mean (range) | 29.8% (17.8–41.8) | 25.0% | 0.0% |

| Facilitate patient talk, prompt patient to speak | |||

| Contributing studies | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Mean (range) | 37.6% (28.8–46.3) | 39.3% | 0.0% |

| Provide information to physician, clarify, expand patient history | |||

| Contributing studies | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Mean (range) | 35.7% (23.3–51.0) | 43.3% (18.8–61.1) | 65.0% |

| Make sure physician listens to patient | |||

| Contributing studies | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Mean (range) | 30.0% (15.1–44.8) | 34.4% (20.8–48.0) | 0.0% |

| Help patient understand, explain physician’s instructions | |||

| Contributing studies | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Mean (range) | 33.2% (20.5–49.3) | 37.5% | 0.0% |

| Help translate language/help with language | |||

| Contributing studies | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Mean (range) | 8.2% (3.3–13.0) | 11.0% | 0.0% |

| Information Seeking | |||

| Help remember, take notes, make requests | |||

| Contributing studies | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Mean (range) | 45.1% (44.1–46.0) | 48.0% | 17.0% |

| Ask questions, request explanations | |||

| Contributing studies | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Mean (range) | 41.4% | 86.1% | 48.0% |

Contributing studies: Glasser, Prohaska, Schilling, Silliman, and Wolff.

DISCUSSION

This study finds that family companions are commonly present in older adults’ routine medical visits and that they typically accompany patients who are older, less educated, and who have more extensive physical and mental health needs than patients who are unaccompanied. Drawing from studies that were conducted in a range of settings and that employed a variety of methodological approaches, 37% of adult patients were found to be accompanied to routine medical visits by a family companion, most commonly by a spouse or adult child. Our synthesis of the available evidence finds the presence of a companion to have a bearing on the duration and structure of medical visits.

The studies that we reviewed did not systematically address patient outcomes, and our findings are therefore subject to uncertain biases emanating from selective reporting. Although we cannot make definitive conclusions, the evidence in two contributing studies favored accompanied (as compared with unaccompanied) patient outcomes and were more recent and methodologically rigorous than studies that were inconclusive. There was no evidence to suggest that accompanied patient outcomes were inferior. Inherent differences in accompanied and unaccompanied patient attributes challenge our ability to disentangle the extent to which outcomes may be directly attributed to family companion presence and/or behaviors. For example, given the longer duration of accompanied patient visits, it is possible that favorable effects might be at least partially attributed to opportunity for more extensive information exchange. However, that outcomes were consistently favorable among accompanied patients when family companions were more verbally active suggests that is not simply the presence of family companions, but the roles they assume that have a bearing for patient outcomes.

Physicians were found to provide more biomedical information to patients when a companion was present, and results suggest that they were also less apt to engage in social conversation. These patterns are consistent with the broader literature on physician communication with patients who are sick, which find associated emotional negativity, anger, and lower satisfaction among patients and physicians (Hall, Milburn, Roter, & Daltroy, 1998; Hall, Roter, Milburn, & Daltroy, 1996). Although accompanied patients were disproportionately sick, we found no evidence to suggest they had lower satisfaction. In fact, the only statistically significant effect in this regard indicated that satisfaction was higher among accompanied patients (Wolff & Roter, 2008). Additional research is needed to clarify the processes at play. We surmise that the presence of a companion might improve medical visit communication processes. Recognizing that their affect and behaviors may be scrutinized, physicians may be more self aware, attentive, and positive when a companion is present. The social role function of family companions was highly endorsed by surveyed patients, companions, and physicians, and it could be that patients feel more confident and better supported during physician visits in the presence of a companion. Companions might also directly influence visit dynamics in ways that benefit patients – by advocating for their wishes or provider attention, ensuring that patient concerns are discussed, or supplying information regarding patients’ health.

Accompanied patient visits were approximately 5 minutes longer than unaccompanied visits, which is not surprising given the greater degree of medical complexity and more advanced age of accompanied patients. Although patient contribution to medical dialogue was significantly lower when accompanied by a family companion then when not accompanied, we believe companions typically compensate and complement patient dialogue. Observational studies indicate companions are more active in dialogue when with patients who are cognitively impaired (Schmidt, Lingler, & Schulz, 2009), emotionally distressed (R. Street & Gordon, 2008), and who anticipate their direct involvement (Ishikawa, Roter, Yamazaki, & Takayama, 2005). Clayman found companions of older and sicker patients were more likely to facilitate patient and physician understanding, and that accompanied older patients whose companions prompted their involvement were 4.5 times more likely to be involved in decision-making.

The success of patient self management activities ultimately hinges on actions undertaken at home and in the community, and we speculate that family companion involvement extends to these ongoing daily activities. A large literature provides compelling evidence that social support has a bearing on a range of valued health outcomes (Seeman, 2000). For example, a meta-analysis of the social support and medical treatment adherence literature concluded that individuals who received practical support were 3.6 times more adherent than individuals without such support (DiMatteo, 2004). Operative pathways might include physiologic regulatory mechanisms, (e.g. stress processes, immune functioning), as well as attitudes and health behaviors (e.g. smoking, diet, exercise, treatment adherence;(Seeman, 2000), which are particularly relevant to chronic care self management.

On the balance, we note a lack of information regarding the dynamics of patient-companion-physician communication processes that is striking given the high frequency of patient accompaniment. Few published observational studies of patient- companion-provider visit dialogue were identified, and available evidence was of variable quality. In the aggregate, the limited numbers of studies, the heterogeneity of study measures and outcomes, and the lack of information regarding specific functions assumed by family companions hinders our understanding of which actions are most relevant and helpful within the context of physician visits. We were not able to examine constructs such as family cohesion/dysfunction, types of patients’ disease or treatment, or patient/companion relationship, all of which may moderate the relationship between family companion presence or behaviors and outcomes of care.

We cannot comment on studies that did not meet our inclusion criteria – for example studies that describe family involvement in pediatric, psychiatric, or end of life care, genetic counseling, or the care of hospitalized or severely sick patients. Despite considerable effort to identify relevant research, it is possible that some papers may have been inadvertently missed. Other relevant studies were excluded if they employed qualitative analytic techniques or if results could not be pooled for analysis. For example, a multi-component oncology communication intervention that focused on improving physician communication skills within the context of three-person consultative visits was excluded from our analyses as findings were limited to examination of intervention effects in relation to physician communication (Delvaux, Merckaert, Marchal, Libert, Conradt, Boniver et al., 2005). Papers included in this review disproportionately were conducted in the United States and sampled older adults. Findings are therefore less generalizeable to working age adults.

Despite its limitations, this study establishes that family companions commonly accompany older adult patients to routine medical visits, and that accompanied patients are disproportionately vulnerable across socio-demographic and health dimensions. Findings suggest a potential role for companions in facilitating information exchange, ameliorating patient sensory, cognitive, or literacy deficits, and facilitating better quality care for relatively socially disadvantaged patient populations. In conjunction with our conceptual framework, results from this study suggest future directions for research to further elucidate optimal patient-provider-companion communication processes, to clarify barriers and facilitators to engaging companions in chronic care processes, and to identify approaches that more effectively recognize and systematically integrate family in chronic care delivery processes.

Practical issues that facilitate or impede the productivity of patient-family-provider partnerships merit consideration. Bioethical concerns regarding consequences for patient autonomy, confidentiality, and the quality of the patient-physician relationship may lead some physicians to discourage families from accompanying patients in the exam room. Concerns about additional time and the potential for patient-family conflict may inhibit the extent to which physicians engage family companions in medical visit dialogue. Incorporating families in dialogue is a departure from traditional patient-provider communication patterns and may generate confusion and role ambiguity for patients, families, and physicians. For example, without extensive knowledge of the patient-companion relationship, providers may predominantly direct their attention to the patient or their family companion, inadvertently limiting or diminishing the contribution of the third party. During visits with patients who are less literate, cognitively impaired, or non-native English speakers, physicians might judge communication with family companions to be more productive and/or efficient; thereby marginalizing patients in discussion about their own care.

Although high quality patient-family-physician communication processes have not been specifically articulated, interventions to improve such processes might nevertheless be formulated. Decision aid and coaching interventions have been shown to improve patients’ knowledge and participation in decisions (O’Connor, Stacey, Entwistle, H, Rovner, Holmes-Rovner et al., 2003; Rao, Anderson, Inui, & Frankel, 2007). Relevant “coach” skills include preparing patients in advance of a medical visit to raise questions and concerns and to communicate and negotiate with doctors (O’Connor, Stacey, & Legare, 2008); activities that family companions were commonly reported by patients and physicians as performing. In light of operational barriers to diffusing decision support/coaching interventions and a criticism that they are poorly linked with primary care, whether family companions might be prepared to assume some aspects of this role merits consideration. Interventions that clarify or attempt to align patients’ expectations and family companions’ anticipated roles in medical visit dialogue have been suggested as a mechanism to improve interpersonal processes during accompanied patient encounters (Ishikawa, Roter, Yamazaki, Hashimoto, & Yano, 2006). From the standpoint that patient and physician interventions have both been shown to improve dialogue (Rao et al., 2007), new approaches and educational initiatives to more clearly articulate triadic communication strategies might prove viable to improving patient-companion-physician communication processes.

In conclusion, this study establishes that families are not only commonly present, but also engaged in medical visit dialogue during routine physician visits. That family companions were commonly reported to facilitate information exchange within medical encounters suggests their presence and involvement may benefit coordination of care and health care management activities in the community. The extent to which family companions fulfill a unifying function within the fragmented health system, or implications of family coordination of care efforts has to our knowledge not been studied. Care management, defined as “a set of activities designed to assist patients and their support systems in managing medical conditions and related psychosocial problems” (Bodenheimer & Berry-Millett, 2009) conceptually embraces families as salient to health care processes, however, specific evidence around how providers should integrate family companions in routine medical visits does not yet exist. In light of less than overwhelming results from recent chronic care interventions (Peikes, Chen, Schore, & Brown, 2009), and the high frequency of patient accompaniment, approaches to maximize the efficiency of family companions’ presence within routine medical encounters merit additional consideration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grant K01MH082885 “Optimizing Family Involvement in Late-Life Depression Care” (JLW).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jennifer L. Wolff, Email: jwolff@jhsph.edu, Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, MD UNITED STATES

Debra L Roter, Email: droter@jhsph.edu, Johns Hopkins University.

References

- Arora N, McHorney C. Patient preferences for medical decision making: who really wants to participate? Med Care. 2000;38(3):335–341. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200003000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berwick DM. What ‘patient-centered’ should mean: confessions of an extremist. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(4):w555–565. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Berry-Millett R. Follow the money--controlling expenditures by improving care for patients needing costly services. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1521–1523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0907185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49(5):651–661. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Farwell W, Jha A. Primary care visit duration and quality: does good care take longer? Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(20):1866–1872. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinn S. A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2000;19(22):3127–3131. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20001130)19:22<3127::aid-sim784>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christakis N, Allison P. Mortality after the hospitalization of a spouse. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(7):719–730. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa050196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayman M, Roter D, Wissow L, Bandeen-Roche K. Autonomy-related behaviors of patient companions and their effect on decision-making activity in geriatric primary care visits. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(7):1583–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delvaux N, Merckaert I, Marchal S, Libert Y, Conradt S, Boniver J, et al. Physicians’ communication with a cancer patient and a relative: a randomized study assessing the efficacy of consolidation workshops. Cancer. 2005;103(11):2397–2411. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo M. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2004;23(2):207–218. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards A, Elwyn G, editors. Shared decision-making in health care: Achieving evidence-based patient choice. USA: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Eggly S, Penner L, Greene M, Harper F, Ruckdeschel J, Albrecht T. Information seeking during “bad news” oncology interactions: Question asking by patients and their companions. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(11):2974–2985. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ende J, Kazis L, Ash A, Moskowitz M. Measuring patients’ desire for autonomy: decision making and information-seeking preferences among medical patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4(1):23–30. doi: 10.1007/BF02596485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella K, Epstein R. So much to do, so little time: care for the socially disadvantaged and the 15-minute visit. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(17):1843–1852. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.17.1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerteis M, Edgman-Levitan S, Daley J. Understanding and Promoting Patient-centered Care. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1993. Through the Patient’s Eyes. [Google Scholar]

- Glynn S, Cohen A, Dixon L, Niv N. The potential impact of the recovery movement on family interventions for schizophrenia: opportunities and obstacles. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(3):451–463. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J, Epstein A, DeCiantis M, McNeil B. Physicians’ liking for their patients: more evidence for the role of affect in medical care. Health Psychol. 1993;12(2):140–146. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J, Horgan T, Stein T, Roter D. Liking in the physician--patient relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(1):69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J, Milburn M, Roter D, Daltroy L. Why are sicker patients less satisfied with their medical care? Tests of two explanatory models. Health Psychol. 1998;17(1):70–75. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J, Roter D, Katz N. Meta-analysis of correlates of provider behavior in medical encounters. Med Care. 1988;26(7):657–675. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J, Roter D, Milburn M, Daltroy L. Patients’ health as a predictor of physician and patient behavior in medical visits. A synthesis of four studies. Med Care. 1996;34(12):1205–1218. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199612000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute TM. The Care Model: Expanded Chronic Care Model. Seattle, WA: [Google Scholar]

- IOM. Retooling for an aging America: Building the health care workforce. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa H, Roter D, Yamazaki Y, Hashimoto H, Yano E. Patients’ perceptions of visit companions’ helpfulness during Japanese geriatric medical visits. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa H, Roter D, Yamazaki Y, Takayama T. Physician-elderly patient-companion communication and roles of companions in Japanese geriatric encounters. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(10):2307–2320. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen J, van Weert J, Wijngaards-de Meij L, van Dulmen S, Heeren T, Bensing J. The role of companions in aiding older cancer patients to recall medical information. Psychooncology. 2009 doi: 10.1002/pon.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson W, Kao A, Kuby A, Thisted R. Not all patients want to participate in decision making. A national study of public preferences. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(6):531–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.04101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makoul G. Essential elements of communication in medical encounters: the Kalamazoo consensus statement. Acad Med. 2001;76(4):390–393. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200104000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray E, Charles C, Gafni A. Shared decision-making in primary care: tailoring the Charles et al. model to fit the context of general practice. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;62(2):205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor A, Stacey D, Entwistle VH, L-T, Rovner D, Holmes-Rovner M, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2003 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor A, Stacey D, Legare F. Coaching to support patients in making decisions. BMJ. 2008;336(7638):228–229. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39435.643275.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peikes D, Chen A, Schore J, Brown R. Effects of care coordination on hospitalization, quality of care, and health care expenditures among Medicare beneficiaries: 15 randomized trials. JAMA. 2009;301(6):603–618. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao JK, Anderson LA, Inui TS, Frankel RM. Communication interventions make a difference in conversations between physicians and patients: a systematic review of the evidence. Med Care. 2007;45(4):340–349. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254516.04961.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R, editor. Meta-analytic procedures for social research. Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R, DiMatteo M. Meta-analysis: recent developments in quantitative methods for literature reviews. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:59–82. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roter D, Hall J. Patient-physician communication: a descriptive summary of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 1988;12:99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Roter D, Stewart M, Putnam S, Lipkin M, Stiles W, Inui T. Communication patterns of primary care physicians. JAMA. 1997;277(4):350–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid Mast M, Hall J, Roter D. Caring and dominance affect participants’ perceptions and behaviors during a virtual medical visit. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):523–527. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0512-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt KL, Lingler JH, Schulz R. Verbal communication among Alzheimer’s disease patients, their caregivers, and primary care physicians during primary care office visits. Patient Educ Couns. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman T. Health promoting effects of friends and family on health outcomes in older adults. Am J Health Promot. 2000;14(6):362–370. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-14.6.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street R, Gordon H. Companion participation in cancer consultations. Psychooncology. 2008;17(3):244–251. doi: 10.1002/pon.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street RL, Jr, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74(3):295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai-Seale M, McGuire T, Zhang W. Time allocation in primary care office visits. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(5):1871–1894. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00689.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickrey B, Mittman B, Connor K, Pearson M, Della Penna R, Ganiats T, et al. The effect of a disease management intervention on quality and outcomes of dementia care: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):713–726. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff J, Roter D. Hidden in plain sight: Medical visit companions as a quality of care resource for vulnerable older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(13):1409–1415. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.13.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.