Abstract

Relapse is a hallmark of cocaine addiction. Cocaine-induced neuroplastic changes in the mesocorticolimbic circuits critically contribute to this phenomenon. Preclinical evidence indicates that relapse to cocaine-seeking behavior depends on activation of dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area. Thus, blocking such activation may inhibit relapse. Because activity of dopamine neurons are regulated by D2-like autoreceptors expressed on somatodendritic sites, this study, using the reinstatement model, aimed to determine whether activation of D2-like receptors in the ventral tegmental area can inhibit cocaine-induced reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior. Rats were trained to self-administer intravenous cocaine (0.25 mg/infusion) under a modified fixed-ratio 5 schedule. After such behavior was well learned, rats went through extinction training to extinguish cocaine-seeking behavior. Then the effect of quinpirole, a selective D2-like receptor agonist microinjected into the ventral tegmental area on cocaine-induced reinstatement was assessed. Quinpirole (0 – 3.2 μg/side) dose-dependently decreased cocaine-induced reinstatement and such effects were reversed by the selective D2-like receptor antagonist eticlopride when co-microinjected with quinpirole into the ventral tegmental area. The effect appeared to be specific to the ventral tegmental area because quinpirole microinjected into the substantia nigra had no effect. Because D2-like receptors are expressed on rat ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons projecting to the prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens, our data suggest that these dopamine circuits may play a critical role in cocaine-induced reinstatement. The role of potential changes in D2-like receptors and related signaling molecules of dopamine neurons in the vulnerability to relapse was discussed.

Keywords: dorsal prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, relapse, neuroplasticity

Introduction

Relapse is a key feature of cocaine addiction (Washton and Stone-Washton, 1990; O’Brien and McLellan, 1996). Cocaine-induced neuroplastic changes in the mesocorticolimbic dopamine (DA) circuits are critically involved in this phenomenon (Wolf et al., 2004; Kalivas et al., 2009; Koob, 2009; Wise, 2009). Recent research has begun to identify relevant cellular and molecular changes in these circuits. For example, self-administered cocaine increases glutamate input to the ventral tegmental area (VTA), the origin of the mesocorticolimbic DA circuits, (You et al., 2007) and induces long-term potentiation (LTP) at excitatory synapses onto DA neurons (Chen et al., 2008). We recently showed that blockade of ionotropic glutamate receptors in the VTA inhibits cocaine-induced reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior (Sun et al., 2005). Together, these data support the idea that glutamate-mediated excitation of DA neurons in the VTA may be a critical mechanism involved in relapse.

It is known that DA neurons in the VTA project to several brain regions including the prefrontal cortex (PFC), nucleus accumbens (NAcc) and amygdala. In addition, these circuits are largely segregated, i.e., DA neurons projecting to the PFC rarely send axonal collaterals to the NAcc or amygdala and vice versa (Carr and Sesack, 2000; Margolis et al., 2006; Margolis et al., 2008). Although glutamate-mediated activation of DA neurons appears to be critically involved in cocaine-induced reinstatement, it is still unclear which of these circuits is activated during reinstatement. The ability to selectively manipulate these circuits is critical to our understanding the role of these circuits in relapse. Recent evidence indicates that these circuits are regulated by different receptors. For example, functional D2-like receptors are selectively expressed in a subpopulation of VTA DA neurons (Lammel et al., 2008; Margolis et al., 2008). In rats, these receptors are expressed on the neurons projecting to the PFC and NAcc but not on the neurons projecting to the amygdala (Margolis et al., 2008). It is well known that D2-like receptors as autoreceptors play a critical role in regulating activity of DA neurons (Bunney and Grace, 1973; Groves et al., 1975; Lacey et al., 1987; Johnson and North, 1992). Consistent with this idea, quinpirole, a selective D2-like receptor agonist, hyperpolarizes the membrane potentials of VTA DA neurons projecting to the PFC and NAcc but not neurons projecting to the amygdala (Margolis et al., 2008). Thus, activation of rat VTA D2-like receptors will selectively inhibit the VTA-PFC and VTA-NAcc DA circuits with a minimal effect on the VTA-amygdala DA circuit. This knowledge provides an exciting opportunity for us to selectively manipulate these circuits and thus help to understand the roles of these circuits in relapse. Because we recently showed that activation of DA receptors in the dorsal PFC (dPFC) is required for cocaine-induced reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior, we propose that the VTA-dPFC DA circuit may be a critical neural substrate involved in this process (Sun and Rebec, 2005). If so, we predict that activation of D2-like receptors in rat VTA should block cocaine-induced reinstatement. The current study aimed to test this hypothesis.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (300–350 g) (Harlan Industries, Indianapolis, IN) were housed individually in plastic home cages in a temperature- and humidity-controlled colony room on a 12-h reverse light-dark cycle (lights off at 08:00). One week before operant training rats were placed on a restricted diet to reach 85–90% free-feeding weight. After training, free access to food was available for one week before and after surgery. Food restriction was then reinstated to maintain 85–90% of free-feeding weight throughout the experiments. Water was always available except during the experimental sessions. The experiments were conducted during the dark cycle (between 09:00 and 18:00). All procedures followed the National Institute of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by University of Tennessee Health Science Center Animal Care and Use Committee.

Operant Training

Rats were first trained to press a lever for food pellets with a fixed-ratio 1 (FR 1) schedule in a standard operant chamber. Each lever press was reinforced by one 45 mg food pellet (Research Diet, New Brunswick, NJ) followed by a 5 s timeout during which lever presses had no programmed consequences. After rats earned 60 pellets within 30 min under FR1, the schedule gradually increased to FR 5. The training continued until the rats obtained 60 pellets within 30 min under FR 5.

Surgery

Rats were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine and xylazine (80 and 10 mg/kg, respectively, intramuscular). Details of catheterization of the jugular vein and brain implantation of guide cannulas are described elsewhere (Caine et al., 1999; Sun et al., 2005). The coordinates for the VTA were: AP, −5.6 mm, ML, ±0.3 mm, and DV, −8.0 mm (relative to bregma, midline and skull surface, respectively). The coordinates for the substantia nigra (SN) were the same as for the VTA except that the ML was ±2.0 mm. An obturator (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) was inserted into each guide cannula to prevent blockage. After surgery, all rats were allowed to recover for one week during which 0.1 ml of gentamicin (10 mg/ml, Biowhitaker, Walkersville, MD) was injected through the catheter daily, and the catheter was also flushed twice a day with heparinized physiological saline (30 U/ml). Catheter patency was evaluated by injecting 0.1 ml Brevital (1%) through the catheter as necessary. Loss of muscle tone within 5 s after injection indicates a patent catheter.

Cocaine and Food SA Training

For cocaine SA training, rats were trained to press a lever for intravenous (i.v.) cocaine in a daily 2 hr session under a modified FR5 (mFR5) schedule. The mFR5 schedule is the same as the FR5 schedule except that the first response is reinforced and subsequent responses are reinforced with the FR5 schedule. The reason for choosing the FR 5 schedule was based on our informal observation that the rats trained under such a schedule showed a higher level of reinstatement compared with the rats trained under FR1. The enhanced reinstatement would increase the ability to detect the inhibitory effect of quinpirole. Cocaine (0.25 mg) was infused in a volume of 0.1 ml over a 2 s period accompanied by a compound stimulus, which consisted of two flashing cue lights and a tone. The stimulus began with onset of infusion of cocaine and ended 20 s later; during the 20 s period, responding was recorded but had no programmed consequences. The active lever was either the left or right lever counterbalanced among rats. The session ended when 2 hr passed or 60 infusions were delivered, whichever occurred first. Rats were trained for 5–7 days per week until they reached the training criterion (the number of cocaine infusions varied by < 20% in three consecutive training sessions). For food SA, rats were trained with the same schedule except that both levers were retracted for 20 s after each reinforcement. This arrangement was aimed to simulate the situation during cocaine SA where cocaine was not available during the period. The session ended when 60 min passed or 100 pellets were delivered. Rats were trained for 5–7 days per week and the training continued until the response rate varied by < 10% in three consecutive training sessions.

Extinction

Extinction training was conducted in daily 60 min sessions for both food and cocaine groups. During the session, responding was recorded but had no programmed consequences. Extinction training continued for a minimum of 5 days and until the response rate fell below 20% of the level during the last cocaine SA session or below 10% of the level during the last food SA session. Because the food group showed a higher level of response rate compared with the cocaine group during SA training different extinction criteria was used here to attempt to make the responding levels in the two groups comparable. Responses typically fell below 20 responses/hr after 5-day extinction training.

Reinstatement

For cocaine-induced reinstatement, rats received intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 10 mg/kg cocaine 5 min before the 1 hr test session. Responding on either lever had no consequences. For food-induced reinstatement, the 1 hr session started with non-contingent delivery of 5 trains of food pellets every 30 s. Each train consisted of 3 food pellets spaced 4 s apart. Thereafter, the same 5 trains was delivered every 60 s, 120s, and 240 s. Thus, a total of 60 pellets were delivered. This arrangement was based on our concern with the time course effect of cocaine priming. Most responses (~85%) occurred within 40 min after cocaine priming suggesting that the priming effect lasted up to 40 min. Thus, we aimed to deliver food pellets within 40 min to simulate the time course. Responding during reinstatement had no programmed consequences.

Microinjection and Testing Procedures

Quinpirole was bilaterally microinjected into the brain regions in a volume of 0.3 μl through 33 ga injection cannulas (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA), which extended 2 mm below the guide cannulas. The volume was delivered over a 1 min period and the injection cannulas stayed in place for another minute to ensure quinpirole diffusion.

The dose-response effects of quinpirole in the VTA on cocaine-induced reinstatement were studied based on a within-subject design. After SA training, rats received extinction training until their responding reached the extinction criteria. The reinstatement test was conducted the next day. Rats received bilateral microinjection of different doses of quinpirole (0.32, 1, 3.2 μg/side) or the drug vehicle into the VTA 5 min before the session followed by an i.p. injection of 10 mg/kg cocaine. The testing order for the doses was randomized and counterbalanced among rats. Tests were typically conducted on Tuesdays and Fridays and extinction training continued between the test sessions until responding returned to the pre-test level, which usually took 1–2 days. To determine whether the effect of quinpirole was mediated by D2-like receptors, we studied whether the D2-like receptor antagonist eticlopride could reverse the effect of quinpirole. To this end, the effect of co-microinjection of eticlopride and quinpirole (1 μg/side of eticlopride+ 1μg/side of quinpirole) into the VTA on cocaine-induced reinstatement was studied. The dose selection for eticlopride was based on our pilot data that eticlopride at 0.32 μg/side failed to reverse the effect of quinpirole. The minimum effective dose of quinpirole (1 μg/side) that inhibited cocaine-induced reinstatement was selected for this experiment. To determine whether the effect was due to nonspecific disruption of motor behavior, the dose-response effects of quinpirole on food-induced reinstatement of extinguished food-seeking behavior were studied in another group of rats. To determine whether the effect was due to diffusion of quinpirole to neighboring regions, the effect of quinpirole directly microinjected into the SN was also determined in another group of rats. For this experiment, only the drug vehicle and the minimum effective dose of quinpirole were tested.

Histology

After the experiments, rats were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg, i.p.) and transcardially perfused with physiological saline followed by formalin (5%). The brains were removed, soaked in formalin for at least 24 hr and sliced at 100 μm thickness with a vibratome. The sections were mounted on gelatin-coated slides, and stained with cresyl violet. The positions of the microinjection cannulas were inspected under a light microscope.

Drugs

Quinpirole and eticlopride (hydrochloride salts) were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO) and dissolved in physiological saline to prepare different concentrations (0–10.7 mg/ml, salt). The pH of the solutions was adjusted to ~7.0 with sodium hydroxide. Cocaine hydrochloride was obtained from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Bethesda, MD) and was dissolved in physiological saline to prepare a solution with a concentration of 2.5 mg/ml (salt).

Statistics

Responses (lever presses) were recorded during the SA, extinction, and reinstatement sessions. Control data were obtained from the training sessions before the test sessions. A repeated one-way ANOVA was used for analyzing dose-dependent effects and the effects of different doses were compared with Bonferroni’s tests, which were adjusted for multiple comparisons (GraphPad Prism version 5.00 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego California USA, www.graphpad.com). The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

Histology

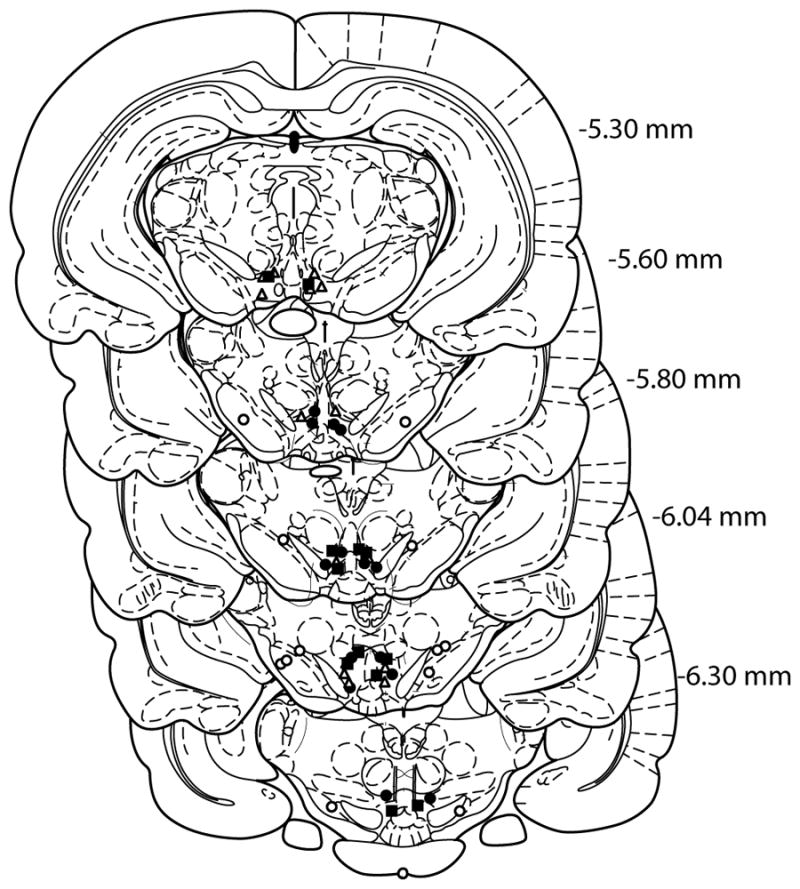

The positions of all microinjection sites are shown schematically in Figure (Fig) 1. All placements were within the VTA or SN.

Fig. 1.

Schematic depiction of microinjection sites in the VTA and SN. Coronal brain section images were adapted from the atlas of Paxinos and Watson (Paxinos G. and Watson C., 1998). Open triangles and circles represent the microinjection sites in VTA food reinstatement and SN cocaine reinstatement groups, respectively. Filled circles and squares represent the microinjection sites in VTA cocaine reinstatement and VTA quinpirole interaction action groups, respectively.

Experiment 1. Effect of Intra-VTA Administration of Quinpirole on Cocaine-induced Reinstatement

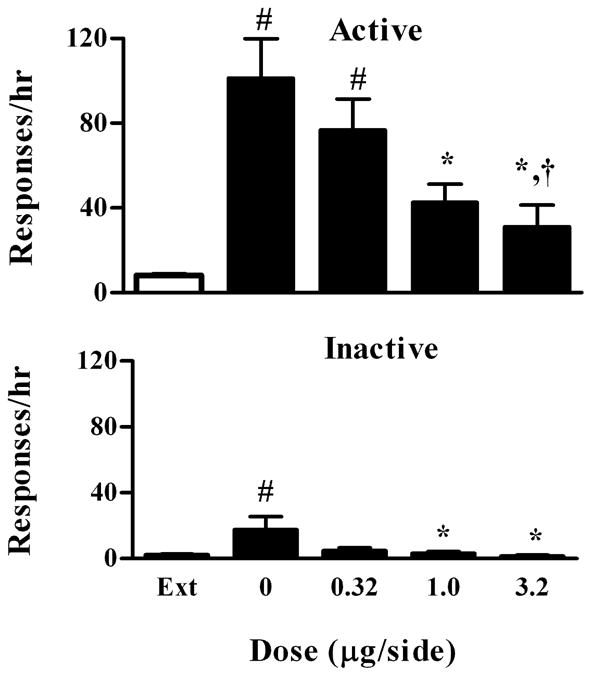

Rats (n=7) for the reinstatement test reached the extinction criteria within 9 days (range: 5–9 days). As shown in Fig 2, a repeated, one-way ANOVA revealed that there were significant dose-dependent effects of quinpirole on cocaine-reinstated responding on the active lever (F4, 24 =12.70, P<0.0001). Specifically, quinpirole significantly decreased responding at 1.0, and 3.2 μg/side (Bonferroni’s tests P< 0.05) compared with the drug vehicle (0 μg/side). In addition, there was a significant difference between the 0.32 and 3.2 μg/side (Bonferroni’s tests P< 0.05). At 1 and 3.2 μg/side, responding on the active lever was no longer different from the extinction level (Bonferroni’s tests P> 0.05). There was also a significant effect of quinpirole on responding on the inactive lever (F 4, 24 =3.88, P=0.03). This was mainly due to one rat that made 56 responses on the inactive lever after the drug vehicle. As a result, there was a significant difference between the doses of 0 and 3.2 μg/side (Bonferroni’s tests P<0.05). Because this data point does not meet the outlier criterion (≥mean±3SD), it was included in the data set.

Fig. 2.

Dose-response effect of intra-VTA quinpirole on cocaine-induced reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Ext indicates the averaged data from the extinction sessions before the reinstatement sessions. Upper panel: Effect on responding on the active lever. Lower panel: Effect on responding on the inactive lever. #, *, and † indicate significant differences from extinction, the drug vehicle and 0.32 μg/side, respectively.

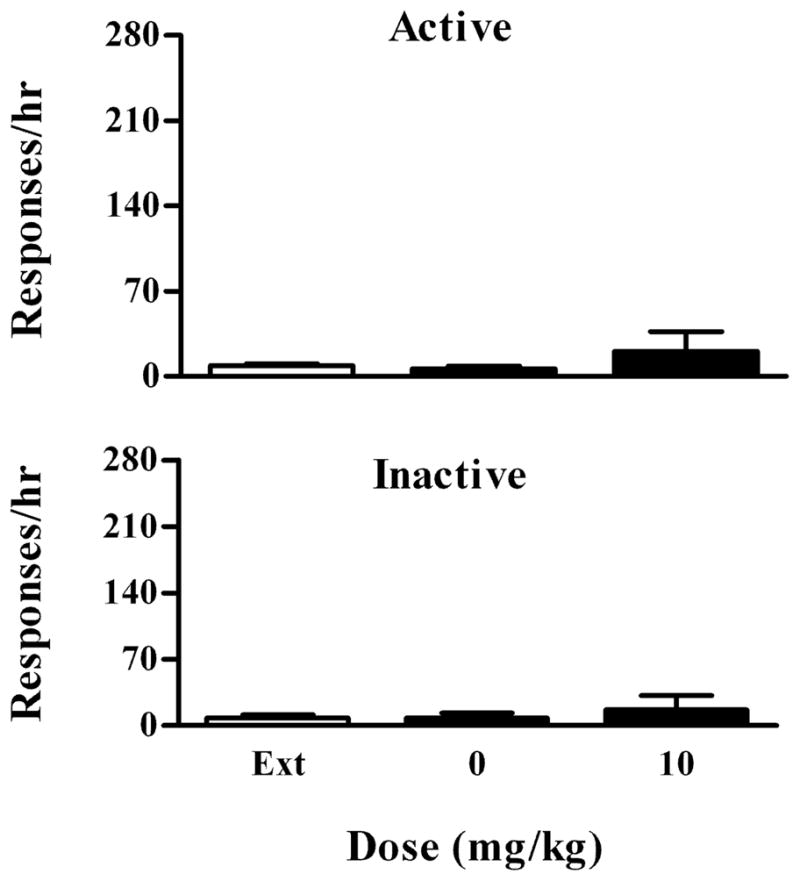

Experiment 2. Effect of Intra-SN Administration of Quinpirole on Cocaine-induced Reinstatement

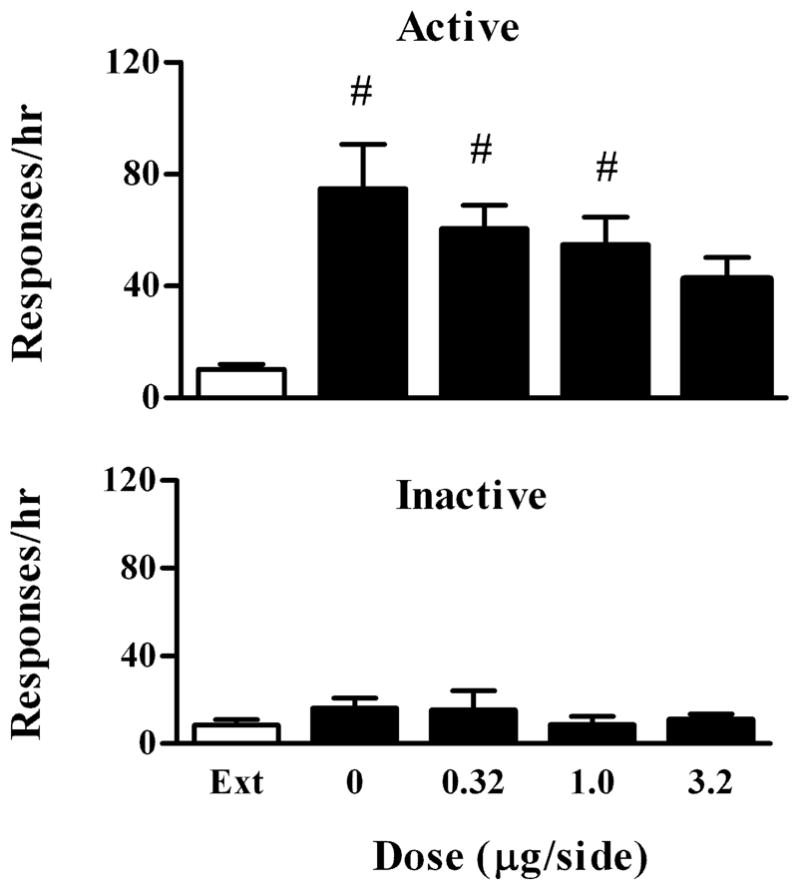

To determine whether the effect of quinpirole in the VTA was due to diffusion into the SN, another DA neuron-rich region, we investigated the effect of quinpirole microinjected into the SN in another group of rats (n=6). As shown in Fig. 3, cocaine significantly reinstated responding on the active lever compared with the extinction level (F 4, 20 =6.08, P=0.002). Quinpirole at the doses of 0.32 and 1 μg/side failed to block cocaine-reinstated responding on the active lever compared with the drug vehicle (Bonferroni’s tests P>0.05). Cocaine- reinstated responding on the active lever was no longer different from the extinction level after 3.2 μg/side of quinpirole. There were, however, no significant differences between the drug vehicle and any doses of quinpirole (Bonferroni’s tests P>0.05). Quinpirole had no effects on responding on the inactive lever (F 4,20 =1.19, P=0.35).

Fig. 3.

Effect of intra-SN quinpirole on cocaine-induced reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Upper panel: Effects on responding on the active lever. Lower panel: Effects on responding on the inactive lever. # indicates significant differences from extinction

Experiment 3. Effect of Co-microinjection of Eticlopride and Quinpirole on Cocaine-induced Reinstatement

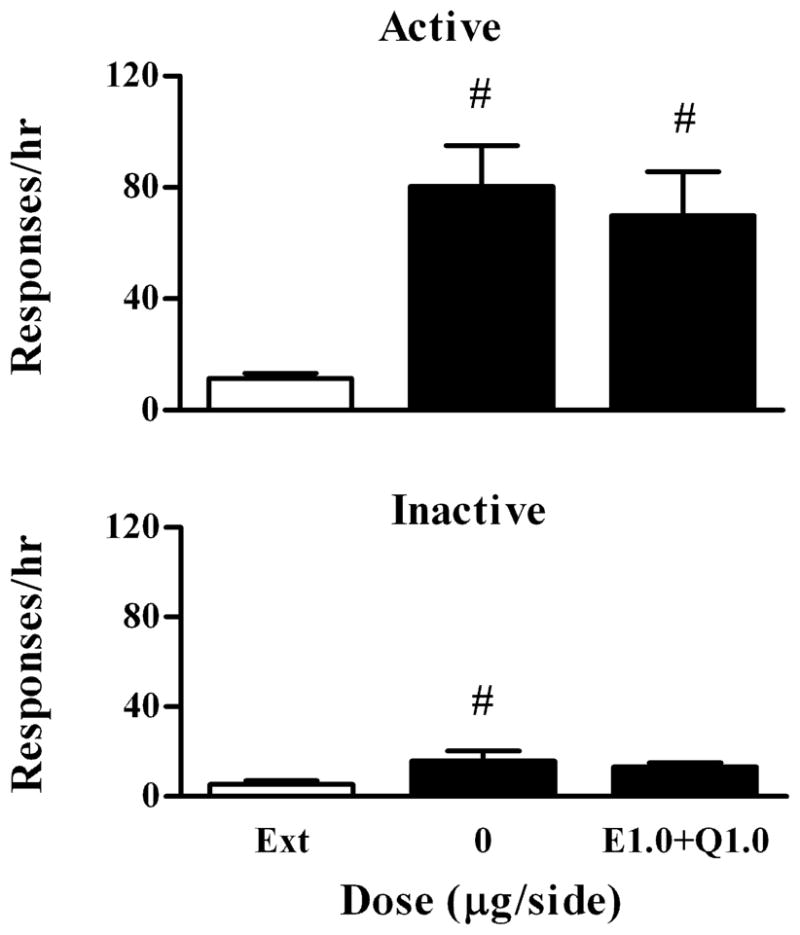

To determine whether the inhibitory effect of quinpirole was mediated by D2-like receptors, we investigated whether the specific D2-like receptor antagonist eticlopride could reverse the effect of quinpirole in another group of rats (n=6). As shown in Fig. 4, cocaine significantly reinstated responding on the active lever compared with the extinction level (F 2, 10 =8.37, P=0.007). In addition, there were no significant differences in the reinstatement levels between combination of eticlopride and quinpirole and the drug vehicle (Bonferroni’s tests P>0.05). A moderate but significant increase in responding on the inactive lever was observed after the drug vehicle compared with the extinction level (Bonferroni’s tests P<0.05). However, there was no significant difference between the combination of quinpirole and eticlopride and the drug vehicle (Bonferroni’s tests P>0.05).

Fig. 4.

Effects of eticlopride on quinpirole-mediated inhibition of cocaine-induced reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. E1.0+Q1.0 indicate the cocaine-induced reinstatement session after eticlopride and quinpirole were co-microinjected into the VTA. Upper panel: Effects on responding on the active lever. Lower panel: Effects on responding on the inactive lever. # indicates significant differences from extinction.

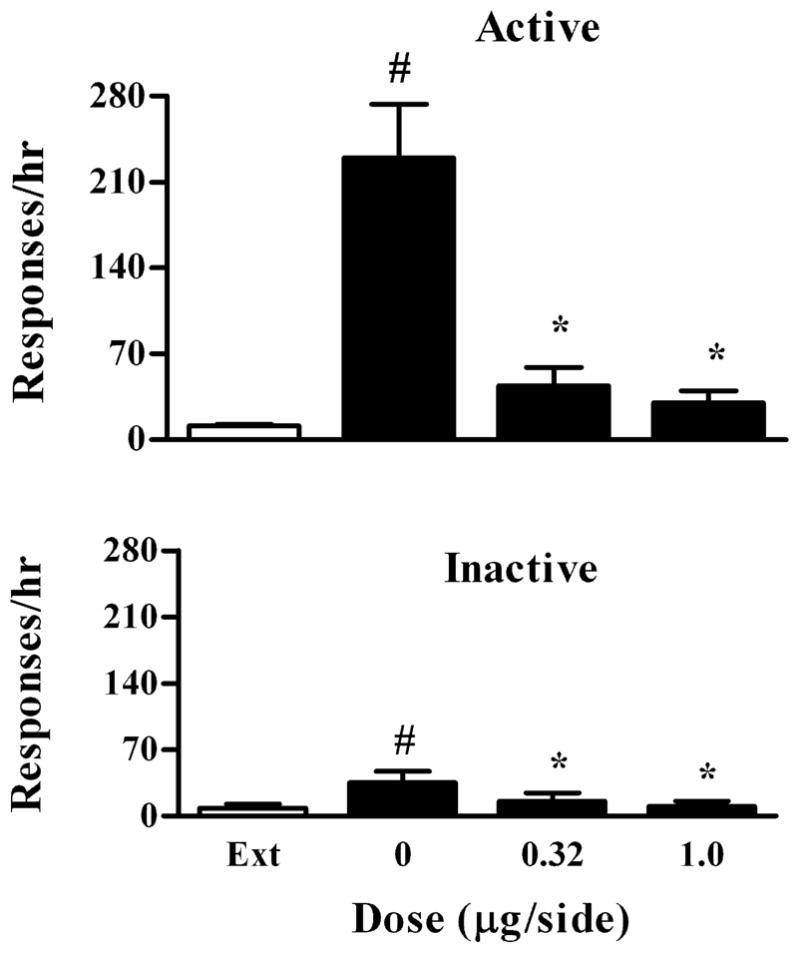

Experiment 4. Effect of Intra-VTA Administration of Quinpirole on Food-induced Reinstatement of Extinguished Food-seeking Behavior

To determine whether the effects of quinpirole on cocaine-induced reinstatement were due to a potential effect on the ability of rats to perform operant behavior, we investigated whether intra-VTA administration of quinpirole can affect the same lever pressing behavior reinstated by food pellets in another group of rats (n=7) with a history of food SA training. As shown in Fig. 5, a repeated one-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of quinpirole on food-induced responding on the active lever (F3, 18 =24.10, P<0.0001). Bonferroni’s tests revealed significant differences between the drug vehicle and the doses of 0.32 and 1 μg/side (P <0.05), respectively. Moreover, the responding levels after the drug were no longer different from the extinction level (P >0.05). There were also significant drug effects on responding on the inactive lever (F2, 12 =8.54, P=0.001). Bonferroni’s tests revealed significant differences between the drug vehicle and the doses of 0.32 and 1 μg/side (P <0.05). This is mainly due to one rat that made 104 responses on the inactive lever after the drug vehicle. However, there was no significant difference between 0.32 and 1 μg/side (P>0.05). Because this data point does not meet the outlier criterion (≥mean±3SD), it was included in the data set.

Fig. 5.

Dose-response effect of intra-VTA quinpirole on food-induced reinstatement of extinguished food-seeking behavior. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Upper panel: Effect on responding on the active lever. Lower panel: Effect on responding on the inactive lever. # and * indicate significant differences from extinction and the drug vehicle, respectively.

Experiment 5. Effect of Cocaine on Food-seeking Behavior in Rats with a History of Food SA

Because rats in the cocaine groups were initially trained to press the lever for food, one concern is that cocaine-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior could partially be attributed to food-seeking behavior. If so, we expect that cocaine should increase extinguished food-seeking behavior in rats with a history of food SA. To test this hypothesis, the rats after Experiment 5 were tested for cocaine-induced reinstatement of food-seeking behavior. Before the test, rats received an i.p. injection of cocaine (10 mg/kg) as in cocaine-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. Responding during the test session (1 hr) had no programmed consequences. Among seven rats tested, six of them made 12 or fewer responses on the active or inactive lever. One rat made 116 and 106 responses on the active and inactive lever, respectively. As shown in Fig. 6, a repeated one-way ANOVA revealed that cocaine failed to reinstate extinguished food-seeking behavior (F2, 6 =0.75, P=0.49).

Fig. 6.

Effect of cocaine (i.p., 10 mg/kg) on food-induced reinstatement of food-seeking behavior in rats with a history of food SA. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Upper panel: Effect on responding on the active lever. Lower panel: Effect on responding on the inactive lever.

Discussion

Our results showed that intra-VTA administration of quinpirole, a selective D2-like receptor agonist, dose-dependently decreased cocaine-induced reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior. These data indicate that activation of D2-like receptors in the VTA might be responsible for the effect. This idea is further supported by our findings that the effect of quinpirole was reversed by a selective D2-like receptor antagonist eticlopride when co-microinjected with quinpirole into the VTA.

Although quinpirole did not significantly inhibit cocaine-induced reinstatement when microinjected into the SN, there was a decreasing trend as the dose increased. Given the small sample size, the effect could reach the significant level with a larger sample size. This raises the concern whether the effect of quinpirole in the VTA resulted from diffusion to the neighboring SN. The dose-response effects of quinpirole microinjected into the VTA and SN, however, indicate that it is highly unlikely that quinpirole would be more potent in the SN than in the VTA even if the sample size of the SN group is increased. Thus, these data strongly support the role of D2-like receptors in the VTA in the inhibitory effect of quinpirole on cocaine-induced relapse to cocaine-seeking behavior.

It has long been known that activation of D2-like receptors hyperpolarizes DA neurons and inhibits their firing activity (Bunney and Grace, 1973; Groves et al., 1975; Lacey et al., 1987; Johnson and North, 1992). It is thought that D2-like receptors act as autoreceptors to exert a negative feedback control on the activity of DA neurons. Consistent with this idea, anatomical studies reveal that D2-like receptors are predominantly expressed on the dendrites of DA neurons whereas the expression on axonal terminals is sparse in the VTA (Sesack et al., 1994). Because the doses of quinpirole used here have previously been shown to inhibit food-induced DA release in the NAcc when microinjected into the VTA (Liu et al., 2008), it is very likely that quinpirole-inhibited relapse was due to inhibition of DA neurons via these autoreceptors. We should point out, however, that there is sparse expression of D2-like receptors on axonal terminals in the VTA indicating that D2-like receptors may act as heteroreceptors to regulate input of other neurotransmitters to the VTA. Indeed, there is evidence that D2-like receptors may regulate glutamate release in the VTA (Koga and Momiyama, 2000). Given the fact that glutamate-mediated activation of VTA DA neurons appears to be critically involved in cocaine-induced reinstatement (McFarland and Kalivas, 2001; Vorel et al., 2001; Sun et al., 2005), we cannot rule out the possibility that activation of these heteroreceptors on the glutamatergic terminals may also contribute to the effect of quinpirole observed here. The predominant location of D2-like receptors on the dendrites of DA neurons, however, suggests that these autoreceptors may contribute to a significant part of the effect.

There is evidence that VTA DA neurons project to different brain regions and that these subpopulations are differentially regulated by D2-like receptors (Lammel et al., 2008; Margolis et al., 2008). In rats, for example, DA neurons projecting to the PFC and NAcc but not the amygdala express D2-like receptors (Margolis et al., 2008). Consistent with this idea, blockade of D2-like receptors in the VTA through reverse dialysis of sulpiride significantly increases the extracellular levels of DA in the ipsilateral PFC in rats (Westerink et al., 1998) suggesting that D2-like receptors in the VTA tonically regulate the activity of the PFC-projecting DA neurons. We and others previously showed that blockade of DA receptors in dorsal PFC inhibits cocaine-induced reinstatement (McFarland and Kalivas, 2001; Sun and Rebec, 2005). These data, together, suggest that the VTA-PFC DA circuit is an important neural substrate involved in cocaine-induced reinstatement. This hypothesis is consistent with our recent results that inhibition of PFC-projecting DA neurons, which express κ-opioid receptors (Margolis et al., 2006), by intra-VTA administration of U 50,488, a selective κ-opioid receptor agonist inhibits cocaine-induced reinstatement in rats (Sun et al., 2010). D2-like receptors are also expressed in the NAcc-projecting DA neurons (Margolis et al., 2008). Thus, intra-VTA administration of quinpirole will also inhibit these neurons and therefore, inhibit DA input to the NAcc (Liu et al., 2008). There is strong evidence that DA input to the NAcc, in particular, the shell subregion plays a role in cocaine-induced reinstatement. For example, blockade of either D1- or D2-like receptors in the shell inhibits cocaine-induced reinstatement (Anderson et al., 2003; Bachtell et al., 2005; Anderson et al., 2006). Conversely, activation of these receptors reinstates extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior in the absence of cocaine (Bachtell et al., 2005; Schmidt et al., 2006). Together, these data suggest that both VTA-PFC and VTA-NAcc DA circuits are involved in cocaine-induced reinstatement.

One concern is that the effect of quinpirole in the VTA could be due to disruption of motor behavior. Several lines of evidence argue against such an explanation. We previously showed that intra-VTA administration of quinpirole failed to affect cocaine-induced locomotion (Steketee and Kalivas, 1992; Steketee and Braswell, 1997). In addition, reversible inactivation of the VTA does not affect either basal or cocaine-induced locomotion (McFarland and Kalivas, 2001). Because the SN plays a more critical role in motor regulation than the VTA (Obeso et al., 2010; Parent and Parent, 2010), the fact that the dose of quinpirole was effective in the VTA but not SN further argues against the motor-related explanation of the effect observed here.

Interestingly, intra-VTA administration of quinpirole also decreased food-induced reinstatement of food-seeking behavior suggesting that either VTADA neurons are involved in both cocaine- and food-seeking behavior or nonspecific motor effects could be responsible. As discussed above, it appears unlikely that the effect of quinpirole can fully be explained by disruption of motor behavior. The fact that quinpirole at a dose of 0.3 μg/side had differential effects on cocaine- and food-seeking behavior further argues against the motor-related explanation of the effect. The DA circuits originated from the VTA are known to play a critical role in general reward processing and motivation (Robinson and Berridge, 2001; Kelley and Berridge, 2002). Thus, it is expected that inhibition of the activity of VTA DA neurons will inhibit reinstatement of food-seeking behavior. It is surprising, however, that the effect of quinpirole was more potent on food-seeking behavior than on cocaine-seeking behavior. The mechanism underlying the difference is unclear at the present time. One possibility is that there exists an enhanced excitatory drive to VTA DA neurons in cocaine SA rats and such an enhanced drive could contribute to the less potent effect of quinpirole. Indeed, cocaine SA induces the long-term potentiation (LTP) at excitatory synapses onto VTA DA neurons for a much longer period (up to 3 months) than food SA (less than 3 weeks) (Chen et al., 2008). In addition, the LTP still exists even after 3-week extinction training in cocaine but not food SA rats (Chen et al., 2008). Because cocaine-induced LTP depends on an increase in the function of postsynaptic AMPA receptors (Ungless et al., 2001; Argilli et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2008), the increased postsynaptic function likely contributes to the enhanced excitatory drive to VTA DA neurons. In addition, cocaine also induces glutamate release in the VTA of rats with a history of cocaine SA (You et al., 2007). It is unknown whether food has a similar effect in rats with a history of food SA. Together, these data indicates that both the presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms may contribute to the enhanced excitatory drive to VTA DA neurons in cocaine SA rats. The less potent effect of quinpirole could result from the enhanced excitatory drive.

Although the enhanced excitatory drive to DA neurons likely plays a role in the differential effects of quinpirole, we cannot totally rule out the possibility that D2-like receptor-mediated responding to quinpirole was different in cocaine and food SA rats. The difference could result from the differences in SA training history given the different nature of cocaine and food. Alternatively, the more enticing hypothesis, in our opinion, is that VTA D2-like autoreceptors-mediated signal transduction may be desensitized or downregulated in VTA DA neurons after chronic cocaine SA. Because cocaine increases extracellular levels of DA in the VTA (Bradberry and Roth, 1989; Chen and Reith, 1994; Reith et al., 1997), it is conceivable that repeated activation of D2-like receptors during cocaine SA training induces neuroplastic changes in the D2-like receptors or related signaling molecules. Downregulation of D2-like receptors after cocaine SA has been reported to occur in the striatum (Moore et al., 1998; Nader et al., 2002). Interestingly, such downregulation has not been observed in the VTA (Moore et al., 1998; Stefanski et al., 2007). Repeated exposures to cocaine, however, reduce the inhibitory effect of apomorphine, a D2-like receptor agonist, on the activity of VTA DA neurons suggesting a decrease in the function of D2-like autoreceptors. Together, these data indicate that downregulation of post-receptor signaling molecules may be involved in the effect of apomorphine. Indeed, AGS3, a member of the activator-of-G-protein-signaling family and RGS9-2, a member of regulators of G protein signaling, are upregulated in the rat PFC and striatum after cocaine SA (Rahman et al., 2003; Bowers et al., 2004). Both AGS3 and RGS9-2 inhibit Gi-mediated signal transduction. Because D2-like receptors are Gi-coupled receptors, upregulation of AGS3 may decrease D2-like receptor-mediated signaling. To the best of our knowledge, we are not aware of evidence that cocaine SA induces upregulation of these proteins in the VTA DA neurons. Future studies are warranted to address this important issue.

In summary, our results demonstrate that activation of D2-like receptors in the VTA decreases cocaine-induced reinstatement in rats. These data are consistent with the idea that VTA-dPFC and/or VTA-NAcc DA circuits are critical neural substrates involved in this process. In addition, the effect of quinpirole on reinstatement was less potent in cocaine SA group than in food SA group. The possibility of downregulation of D2-like receptor-mediated signaling is worth further investigation. Such downregulation could contribute to enhanced response to cocaine or cocaine-related stimuli and thus, enhanced vulnerability to relapse.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH (DA021278, DA023215, DA02451).

Abbreviations

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

- DA

dopamine

- dPFC

dorsal prefrontal cortex

- NAcc

nucleus accumbens

References

- Anderson SM, Bari AA, Pierce RC. Administration of the D1-like dopamine receptor antagonist SCH-23390 into the medial nucleus accumbens shell attenuates cocaine priming-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168:132–138. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SM, Schmidt HD, Pierce RC, Anderson SM, Schmidt HD, Pierce RC. Administration of the D2 dopamine receptor antagonist sulpiride into the shell, but not the core, of the nucleus accumbens attenuates cocaine priming-induced reinstatement of drug seeking. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1452–1461. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argilli E, Sibley DR, Malenka RC, England PM, Bonci A. Mechanism and time course of cocaine-induced long-term potentiation in the ventral tegmental area. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:9092–9100. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1001-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachtell RK, Whisler K, Karanian D, Self DW. Effects of intra-nucleus accumbens shell administration of dopamine agonists and antagonists on cocaine-taking and cocaine-seeking behaviors in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 2005;183:41–53. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers MS, McFarland K, Lake RW, Peterson YK, Lapish CC, Gregory ML, Lanier SM, Kalivas PW. Activator of G protein signaling 3: a gatekeeper of cocaine sensitization and drug seeking. Neuron. 2004;42:269–281. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00159-x. [see comment] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradberry CW, Roth RH. Cocaine increases extracellular dopamine in rat nucleus accumbens and ventral tegmental area as shown by in vivo microdialysis. Neuroscience Letters. 1989;103:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90492-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunney BS, Grace AA. Dopaminergic neurons: effect of antipsychotic drugs and amphetamine on single cell activity. Journal of Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics. 1973;185:560–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caine SB, Negus SS, Mello NK, Bergman J. Effects of dopamine D(1-like) and D(2-like) agonists in rats that self-administer cocaine. Journal of Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics. 1999;291:353–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr DB, Sesack SR. Projections from the rat prefrontal cortex to the ventral tegmental area: target specificity in the synaptic associations with mesoaccumbens and mesocortical neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:3864–3873. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03864.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BT, Bowers MS, Martin M, Hopf FW, Guillory AM, Carelli RM, Chou JK, Bonci A. Cocaine but not natural reward self-administration nor passive cocaine infusion produces persistent LTP in the VTA. Neuron. 2008;59:288–297. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen NH, Reith ME. Autoregulation and monoamine interactions in the ventral tegmental area in the absence and presence of cocaine: a microdialysis study in freely moving rats. Journal of Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics. 1994;271:1597–1610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves PM, Wilson CJ, Young SJ, Rebec GV. Self-inhibition by dopaminergic neurons: an alternative to the “neuronal feedback loop” hypothesis for the mode of action of certain psychotropic drugs. Science. 1975;190:522–529. doi: 10.1126/science.242074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SW, North RA. Opioids excite dopamine neurons by hyperpolarization of local interneurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12:483–488. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00483.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Lalumiere RT, Knackstedt L, Shen H. Glutamate transmission in addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Suppl 1):169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley AE, Berridge KC. The neuroscience of natural rewards: relevance to addictive drugs. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22:3306–3311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03306.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga E, Momiyama T. Presynaptic dopamine D2-like receptors inhibit excitatory transmission onto rat ventral tegmental dopaminergic neurones. Journal of Physiology. 2000;523(Pt 1):163–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00163.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. Neurobiological substrates for the dark side of compulsivity in addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Suppl 1):18–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey MG, Mercuri NB, North RA. Dopamine acts on D2 receptors to increase potassium conductance in neurones of the rat substantia nigra zona compacta. Journal of Physiology. 1987;392:397–416. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammel S, Hetzel A, Hackel O, Jones I, Liss B, Roeper J. Unique properties of mesoprefrontal neurons within a dual mesocorticolimbic dopamine system. Neuron. 2008;57:760–773. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZH, Shin R, Ikemoto S. Dual role of medial A10 dopamine neurons in affective encoding. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:3010–3020. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis EB, Mitchell JM, Ishikawa J, Hjelmstad GO, Fields HL. Midbrain dopamine neurons: projection target determines action potential duration and dopamine D(2) receptor inhibition. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:8908–8913. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1526-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis EB, Lock H, Chefer VI, Shippenberg TS, Hjelmstad GO, Fields HL. Kappa opioids selectively control dopaminergic neurons projecting to the prefrontal cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:2938–2942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511159103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland K, Kalivas PW. The circuitry mediating cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:8655–8663. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08655.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RJ, Vinsant SL, Nader MA, Porrino LJ, Friedman DP. Effect of cocaine self-administration on dopamine D2 receptors in rhesus monkeys. Synapse. 1998;30:88–96. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199809)30:1<88::AID-SYN11>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader MA, Daunais JB, Moore T, Nader SH, Moore RJ, Smith HR, Friedman DP, Porrino LJ. Effects of cocaine self-administration on striatal dopamine systems in rhesus monkeys: initial and chronic exposure. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:35–46. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00427-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien CP, McLellan AT. Myths about the treatment of addiction. Lancet. 1996;347:237–240. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90409-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeso JA, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Goetz CG, Marin C, Kordower JH, Rodriguez M, Hirsch EC, Farrer M, Schapira AH, Halliday G. Missing pieces in the Parkinson’s disease puzzle. Nature Medicine. 2010;16:653–661. doi: 10.1038/nm.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent M, Parent A. Substantia nigra and Parkinson’s disease: a brief history of their long and intimate relationship. Can J Neurol Sci. 2010;37:313–319. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100010209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coodinates. New York: Academic; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman Z, Schwarz J, Gold SJ, Zachariou V, Wein MN, Choi KH, Kovoor A, Chen CK, DiLeone RJ, Schwarz SC, Selley DE, Sim-Selley LJ, Barrot M, Luedtke RR, Self D, Neve RL, Lester HA, Simon MI, Nestler EJ. RGS9 modulates dopamine signaling in the basal ganglia. Neuron. 2003;38:941–952. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00321-0. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reith ME, Li MY, Yan QS. Extracellular dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin in the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens of freely moving rats during intracerebral dialysis following systemic administration of cocaine and other uptake blockers. Psychopharmacology. 1997;134:309–317. doi: 10.1007/s002130050454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. Incentive-sensitization and addiction. Addiction. 2001;96:103–114. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9611038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt HD, Anderson SM, Pierce RC, Schmidt HD, Anderson SM, Pierce RC. Stimulation of D1-like or D2 dopamine receptors in the shell, but not the core, of the nucleus accumbens reinstates cocaine-seeking behaviour in the rat. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;23:219–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesack SR, Aoki C, Pickel VM. Ultrastructural localization of D2 receptor-like immunoreactivity in midbrain dopamine neurons and their striatal targets. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:88–106. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-01-00088.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanski R, Ziolkowska B, Kusmider M, Mierzejewski P, Wyszogrodzka E, Kolomanska P, Dziedzicka-Wasylewska M, Przewlocki R, Kostowski W. Active versus passive cocaine administration: differences in the neuroadaptive changes in the brain dopaminergic system. Brain Research. 2007;1157:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.04.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steketee JD, Kalivas PW. Microinjection of the D2 agonist quinpirole into the A10 dopamine region blocks amphetamine-, but not cocaine-stimulated motor activity. Journal of Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics. 1992;261:811–818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steketee JD, Braswell BC. Injection of SCH 23390, but not 7-hydroxy-DPAT, into the ventral tegmental area blocks the acute motor-stimulant response to cocaine. Behavioural Pharmacology. 1997;8:58–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Rebec GV. The role of prefrontal cortex D1-like and D2-like receptors in cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2005;177:315–323. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1956-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Akins CK, Mattingly AE, Rebec GV. Ionotropic glutamate receptors in the ventral tegmental area regulate cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:2073–2081. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Xue Y-Q, Huang Z-F, Steketee JD. Regulation of reinstated cocaine-seeking behavior by κ-Opioid receptors in the ventral tegmental area of rats. Psychopharmacology. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1812-0. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungless MA, Whistler JL, Malenka RC, Bonci A. Single cocaine exposure in vivo induces long-term potentiation in dopamine neurons. Nature. 2001;411:583–587. doi: 10.1038/35079077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorel SR, Liu X, Hayes RJ, Spector JA, Gardner EL. Relapse to cocaine-seeking after hippocampal theta burst stimulation. Science. 2001;292:1175–1178. doi: 10.1126/science.1058043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washton AM, Stone-Washton N. Abstinence and relapse in outpatient cocaine addicts. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1990;22:135–147. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1990.10472539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerink BH, Enrico P, Feimann J, De Vries JB. The pharmacology of mesocortical dopamine neurons: a dual-probe microdialysis study in the ventral tegmental area and prefrontal cortex of the rat brain. Journal of Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics. 1998;285:143–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Ventral tegmental glutamate: a role in stress-, cue-, and cocaine-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Suppl 1):174–176. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf ME, Sun X, Mangiavacchi S, Chao SZ. Psychomotor stimulants and neuronal plasticity. Neuropharmacology. 2004;1:61–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You ZB, Wang B, Zitzman D, Azari S, Wise RA. A role for conditioned ventral tegmental glutamate release in cocaine seeking. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:10546–10555. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2967-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]