Abstract

Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 (encoded by KCNQ2 and KCNQ3) are homologous subunits forming a widely expressed neuronal voltage-gated K+ (Kv) channel. Hypomorphic mutations in either KCNQ2 or KCNQ3 cause a highly penetrant, though transient, human phenotype--epilepsy during the first months of life. Some KCNQ2 mutations also cause involuntary muscle rippling, or myokymia, which is indicative of motoneuron axon hyperexcitability. Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 are concentrated at axonal initial segments (AISs), and at nodes of Ranvier in the central and peripheral nervous system. Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 share a novel ~80 residue C-terminal domain bearing an “anchor” motif, which interacts with ankyrin-G and is required for channel AIS (and likely, nodal) localization. This domain includes the sequence IAEGES/TDTD, which is analogous (not homologous) to the ankyrin-G interaction motif of voltage-gated Na+ (NaV) channels. The KCNQ subfamily is evolutionarily ancient, with two genes (KCNQ1 and KCNQ5) persisting as orthologues in extant bilaterian animals from worm to man. However, KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 arose much more recently, in the interval between the divergence of extant jawless and jawed vertebrates. This is precisely the interval during which myelin and saltatory conduction evolved. The natural selection for KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 appears to hinge on these subunits’ unique ability to be coordinately localized with NaV channels by ankyrin-G, and the resulting enhancement in the reliability of neuronal excitability.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Kv7 subfamily: scientifically novel, evolutionarily ancient voltage-gated K+ channels

The large “voltage-gated-like” channel superfamily consists of genes for voltage-gated K+, Ca2+ and Na+ and related channel subunits [1]. These channels’ principal subunits possess homologous transmembrane pore and voltage sensor domains, but divergence during evolution has resulted in differences in intrinsic functions (e.g., selectivity among permeant ions, kinetics of opening and closing, sensitivity to voltage, etc.), regulation by protein-protein interactions and second messengers, cell-type pattern of expression, and subcellular localization [2, 3]. Although members of the Kv7 family of voltage-gated K+ channels underlie important and extensively studied currents in heart, nerve, brain, and epithelia, they were the last major group of voltage-gated channels to be cloned, probably due to technical difficulties in RT-PCR of their unusually long, GC-rich transcripts [4]. Though initial cDNA cloning efforts were unrewarded, disease gene hunts ultimately tracked the Kv7 channel genes down. Aided by the mapping of the human genome, a first Kv7 family member expressed in heart was cloned at the genetic locus of the inherited cardiac arrhythmia, long QT syndrome 1 [5]. This gene, initially called KvLQT1, was soon renamed KCNQ1. Subsequently, homologues were cloned at the two loci for the epilepsy syndrome, benign neonatal familial seizures, and named KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 [6–9]. Additional genomic searches allowed cloning of two additional related genes, KCNQ4 and KCNQ5 [4, 10]. Although brought to light only recently, the KCNQ genes are evolutionarily ancient and highly conserved. One gene is present in cnidaria (e.g., jellyfish, EC, unpublished); two genes, orthologous to human KCNQ1 and KCNQ5, are present in bilaterian genomes from worm to man [11, 12]. As discussed below, KCNQ4, and later, KCNQ2 and KCNQ3, evolved more recently by gene duplications in vertebrates [11].

1.2. Kv7 subunits have novel C-terminal domains involved in channel assembly, regulation by membrane phospholipids, and subcellular targeting

The protein products of the KCNQ1–5 genes have been assigned the corresponding names Kv7.1 to Kv7.5 [13], though many papers also refer to the subunit polypeptides and assembled channels as KCNQ1–5. Like nearly all voltage-gated K+ channel subunits, Kv7 subfamily members have 6 transmembrane segments encompassing voltage sensor and pore forming domains, and intracellular N- and C-termini (Fig. 1A). Despite their conventional membrane topology, however, Kv7 subunits differ conspicuously from other Kv subfamilies, in 3 respects: (1) Kv7 subunits lack the N-terminal T1 domain which controls tetramerization in Kv1–Kv4 channels [14, 15]; (2) all Kv7 subunits instead possess a unique tetramerization domain in their C-termini, which bears no homology to T1 [16, 17]; (3) all Kv7 subunits share a conserved domain in the proximal C-terminal region near S6, containing residues which coordinately bind the membrane lipid phosphatidylinositol 4,5 bisphosphate (PIP2) [18, 19]. Lastly, the most C-terminal ~80 residues of the vertebrate-restricted Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 subunits comprise a conserved ankyrin-G binding domain which is absent in all other known genes (including the other Kv7 subunits) [12, 20]. The evolutionary origin and role of this domain as a molecular anchor mediating retention and colocalization with NaV channels at axonal initial segments and nodes of Ranvier is discussed below.

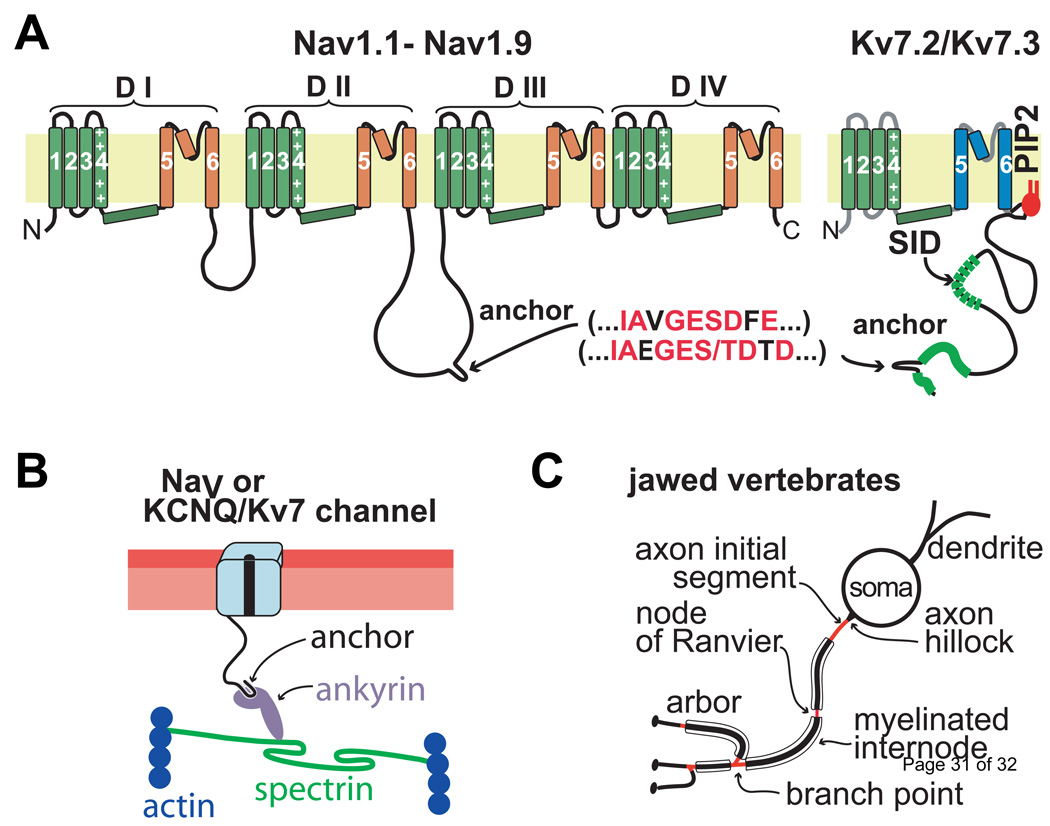

Figure 1. Mammalian NaV and Kv7 channels possess intracellular anchor motifs with similar sequences, mediating their co-clustering at axon initial segments and nodes of Ranvier.

(A) NaV and Kv7.2/Kv7.3 channel transmembrane topology. Locations of Kv7.2/Kv7.3 peptide sequences required for membrane phospholipid interaction (PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate) and tetramerization (SID, subunit interaction domain), and the axonal anchor motifs for both channel types are indicated. B) Proposed molecular interactions between jawed vertebrate axonal NaV and Kv7 channels, ankyrin-G, spectrin, and actin. (C) Cartoon indicating location pattern of ankyrin-G dependent NaV and Kv7.2/Kv7.3 clustering on myelinated axons, which mediate AP initiation and conduction (AISs, nodes, and branch points, red). After [12].

1.3. Kv7 channels gate relatively slowly, and can be reversibly modulated by G-protein coupled receptors, protein-protein interactions, and drugs

Kv7 subunits are the molecular constituents responsible for several important K+ currents previously identified and studied by electrophysiologists. Kv7.1 (along with a small accessory subunit KCNE1) underlies the slow K+ current that repolarizes ventricular myocytes and thereby ends systolic contraction [21]; mutations in either KCNQ1 or KCNE1 cause dominantly or recessively inherited arrhythmias, depending on the severity of the functional defect [22]. KCNQ1 (with KCNE1) and KCNQ4 are both expressed in the inner ear and mutations in each of the genes can cause deafness [23]. Though not known to be linked to disease, Kv7.5 channels are widely expressed in neurons and muscle, and contribute to the medium and slow afterhyperpolarizations that modulate responsiveness in many neurons [24].

Kv7 channels have been characterized functionally through expression in Xenopus oocytes and mammalian cell lines, and through studies of the native currents using drugs to isolate the currents or comparisons between wildtype and Kv7 transgenic mice. All the subunits form channels which are activated very slowly (exponential time constants of ~30 to several 100 ms) by depolarization, non-inactivating, and rapidly inhibited by treatments that deplete membrane PIP2 concentrations and thereby cause PIP2 dissociation from its Kv7 C-terminal binding sites [25]. Many cells, including neurons, possess G-protein coupled receptors that can activate phospholipase C and deplete PIP2 within seconds. Where present, this pathway (GPCR-PLC-PIP2-Kv7 channel) represents a rapid, reversible mechanism for increasing membrane excitability. One exception to this general scheme is noteworthy: coassembly of Kv7.1 with KCNE3 produces a chronically active, voltage-independent “leak” channel, which is important for K+ transport in gastrointestinal and tracheal epithelia [26]. A large number of Kv7 opener drugs have been identified which promote channel opening by shifting the voltage-dependence of activation to hyperpolarized potentials [27]. Thus, Kv7 channels can be modified in their intrinsic function over an exceptionally broad range, from nearly complete inhibition (by the GPCR-PLC-PIP2 depletion mechanism) to chronic, complete activation. Knowledge of the physiological functions served by the exceptional susceptibility of Kv7 channels to these modulations remains quite incomplete. Additional studies have implicated A-kinase anchor proteins, calmodulin, ubiquitination, and phosphorylation in Kv7 modulation (as reviewed recently [18, 28]).

1.4. Kv7 subunit tetramerization is not promiscuous

All K+ channels are formed by four pore modules that together build the ion selective filter and surround the water-filled transmembrane ion pathway. In each of the classical Kv1, Kv2, Kv3, and Kv4 channel subfamilies, coassembly of subunits within a family is permitted promiscuously, but coassembly between subunits of different subfamilies does not occur. By contrast, the 5 mammalian Kv7 subunits have diverged sufficiently to prevent promiscuous coassembly even within the subfamily. Kv7.1 subunits form homotetrameric channels, and can coassemble with the small accessory subunits of the KCNE family, but not with other Kv7 subunits [4]. Kv7.2, Kv7.4, and Kv7.5 can each homotetramerize, and also form heterotetramers with Kv7.3 [29–31]. Kv7.4 and Kv7.5 also can coassemble [32]. Kv7.3 subunits can homotetramerize, but such Kv7.3 homotetramers are non-functional in Xenopus oocytes and yield small currents in most experiments using mammalian cell lines. The cause of absent or diminished Kv7.3 homotetramer surface expression is probably intracellular retention of these channels, and, compelling but surprising evidence implicates a residue near the pore selectivity filter as critical for this [33]. Coassembly of Kv7.2 with Kv7.3 markedly enhances both surface abundance and opening probability, compared to Kv7.2 homotetramers. In sympathetic neurons, functional Kv7.2 homomeric channels are expressed early in development and Kv7.2/7.3 heteromers predominate later [34] The intracellular C-terminal tetramerization domain is critical for setting the limits on Kv7 tetramerization, and residues important for this have begun to be mapped through a combination of mutational and structural studies [16, 17].

2. Kv7.2/Kv7.3 heteromers and Kv7.2 homotetramers underlie two classical neuronal currents: M-current (“IM”) and the slow nodal potassium current (“IKS ”)

2.1. M-current: a releasable restraining force on neuronal excitability

During the 1970s, studies of invertebrate neurons first showed that voltage-channels could be modified in their properties through activation of metabotropic receptors and intracellular messengers, leading to changes in synaptic strength that provided correlates of behavioral adaptation and learning [35]. This paradigm was extended to vertebrates in 1980 when Brown and Adams identified the M-current,or IM, in frog sympathetic neurons [36]. IM was a slowly activating, non-inactivating voltage-gated current that could be nearly completely inhibited by application of acetylcholine or muscarinic agonists. The current required depolarization to be fully activated, but was partially active at rest, thus exerting a hyperpolarizing influence upon the resting membrane potential. IM had no influence on the shape of the action potential—its rates of opening and closing were too slow, and its peak amplitude too small. These slow kinetics, however, allowed IM to activate cumulatively during a long subthreshold depolarization or a burst of action potentials. In this way, the small, slow current could have considerable influence on firing responses, delaying the onset of and/or hastening the termination of a burst of spikes. These findings were later extended to many mammalian central and peripheral neuronal types, indicating that IM was a widely deployed, restraining influence on neuronal firing [2, 37]. Furthermore, many different metabotropic receptors, were, like muscarinic receptors, capable of inhibiting IM, thereby causing increased excitability that might contribute to plasticity at the circuit and behavioral levels.

2.2. The slow nodal current, IKS: a dampener of nodal excitability

Nearly coincident with the discovery of IM, Debois described a second novel K+ current, with similar features, at the node of Ranvier. It had recently been shown that mammalian myelinated fibers lacked a prominent, fast, “delayed rectifier” K+ channel like that present in the squid giant axon and frog myelinated nerve [38, 39]. Dubois showed that myelinated nerves possessed a slowly activating, non-inactivating K+ current that contributed to the resting membrane potential [40, 41]. The amplitude of the nodal slow current, or IKS, was small, about 1/40th that of the Na+ current, yet it exerted a significant influence on firing thresholds, caused adaptation during prolonged depolarizing current injections, and was precisely confined to the unmyelinated gap at the node [42]. Although Dubois noted the similarities between IM and IKS [40] In the absence of molecular information about the two currents or specific pharmacological tools, the relationship between them was not further characterized for over 20 years. The issue was finally illuminated through clinical and genetic studies of human neurological disorders.

2.3. Neonatal epilepsy can be due to mutations in KCNQ2 or KCNQ3

The neurologist Andreas Rett, best remembered for describing Rett’s syndrome, the severe, X-linked neurodevelopmental disorder of girls, also first described a dominantly inherited epilepsy syndrome affecting infants [43]. In this form of epilepsy, called benign familial neonatal seizures, or BFNS, onset occurs precisely in the middle of the first week after term birth; in cases of premature birth, onset is delayed until the equivalent gestational age is reached [44]. Seizures recur, sometimes with great frequency, for up to about 3 months, but they then remit, and outcomes are generally good. Two loci, on chromosome 20 and chromosome 8, were identified by linkage analysis [45, 46]. KCNQ2 was found at the chromosome 20 locus; KCNQ3 was found on chromosome 8 [6–8]. In brain, KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 mRNAs are widely expressed in an overlapping pattern, and brain Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 proteins can be efficiently and reciprocally coimmunoprecipitated [29, 47]. In heterologous cells, the two subunits preferentially coassemble in 2:2 stoichiometry to form channels that recapitulate the IM functional profile [34, 48, 49]. In sympathetic neurons, careful pharmacological profiling reveals that a fraction of IM is mediated by Kv7.2 homotetramers [34].

3. KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 are concentrated at nodes of Ranvier and axon initial segments

3.1. A clinical clue to a Kv7 role on myelinated axons

In several families with seizures due to KCNQ2 mutations, myokymia was also observed [50–52]. Myokymia is a repetitive wave- or wormlike involuntary movement in muscle, with specific features on clinical electromyographic testing, indicative of spontaneous, aberrant, repetitive firing in the axons of lower motor neurons of the brainstem or spinal cord [53]. Mutations in KCNA1, encoding the subunit Kv1.1 which is expressed both in brain and along peripheral axons, cause the human disorder, episodic ataxia with continuous myokymia (or EA-1) [54, 55]. Together, these findings indicated that Kv7.2, like Kv1.1, likely had a role on motor axons. Using Kv7.2 specific antibodies and isolated sciatic nerve fibers, Devaux et al. found that Kv7.2 was precisely colocalized with NaV channels and ankyrin-G at nodes of Ranvier [56]. Subsequent studies showed that Kv7.3 was also highly concentrated at many sciatic nerve nodes, where it colocalized with Kv7.2, NaV channels, and ankyrin-G [20, 57].

3.2. Kv7.2 mediates the IKS in large axons from rat sciatic nerve

Schwarz and colleagues combined in vitro voltage-clamp studies of isolated single axons, in vivo recording from intact nerves, behavioral pharmacology, and immunostaining, to analyze the role of Kv7 channels at the nodes of Ranvier of large motor axons [57]. Under voltage-clamp, the nodal IKS was eliminated by Kv7-selective blockers linopirdine, XE-991, and TEA. The Kv7 selective opener, retigabine, increased IKS and shifted its voltage-dependence to hyperpolarized voltages, effects also seen on IM and heterologously expressed Kv7 subunits [27]. In vivo nerve recordings had previously demonstrated that a period of reduced excitability of about 200 ms occurred after spike trains were elicited by extracellular stimulation [58]. This “late subexcitability” period was eliminated by Kv7 blocker treatment. In vivo, Kv7 blocker treatments abolished adaptation in myelinated motor axons, leading to aberrant repetitive firing. Together, the physiological data strongly suggested that in the largest rat sciatic nerve fibers, which include motoneuron axons, IKS was mediated by Kv7.2 homotetramers. Consistent with this, Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 were colocalized at the nodes of small and medium sized axons (primarily, sensory fibers), but only Kv7.2 could be detected at the largest diameter fibers.

3.3. Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 are localized at many axon initial segments

The node and AIS share many protein components, and in both locations, ankyrin-G plays a central role as an organizing scaffold protein (see reviews by Rasband and Leterrier et al., this volume). Kv7.2/Kv7.3 immunostaining has been found at AISs of many neuronal types in many brain regions, including ventral horn motoneurons, stellate, basket, Purkinge, and granule cells in the cerebellar cortex, pyramidal cells throughout the neocortex and hippocampus, and at the unmyelinated spike initiation zones at afferent endings of the cochlear nerve [20, 56, 59, 60]. This list is far from exhaustive, as a systematic catalogue of Kv7 AIS staining has not been performed. The results described here do not preclude the possibility that in some neurons, a portion of Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 subunits are distributed to locations other than the AIS and nodes, including presynaptic terminals and the soma [34, 61, 62].

4. KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 are retained at AISs by interaction with ankyrin-G

The C-termini of Kv7.3 and Kv7.2 contain peptide sequences that are similar but not identical to the sequence shown to mediate interaction between NaV channels and ankyrin-G (Fig. 1A, Fig. 2C). Evidence indicates that the Kv7 sequence mediates both ankyrin-G interaction and channel concentration at AISs. Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 fail to localize at AISs of cerebellar neurons from transgenic mice lacking ankyrin-G expression in these cells [20, 63]. Transmembrane fusion proteins bearing the intact cytoplasmic Kv7.2 or Kv7.3 C-terminal domains redistribute ankyrin-G to the cell surface of HEK cells. These same fusion proteins are strongly retained at the AISs when expressed by hippocampal neurons in dissociated culture. Both the surface redistribution of Ankyrin-G in HEK cells and targeting of the Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 C-terminal domain–containing fusion proteins to AIS in cultured neurons are abolished by mutation of the putative ankyrin-G interaction motif [20, 64].

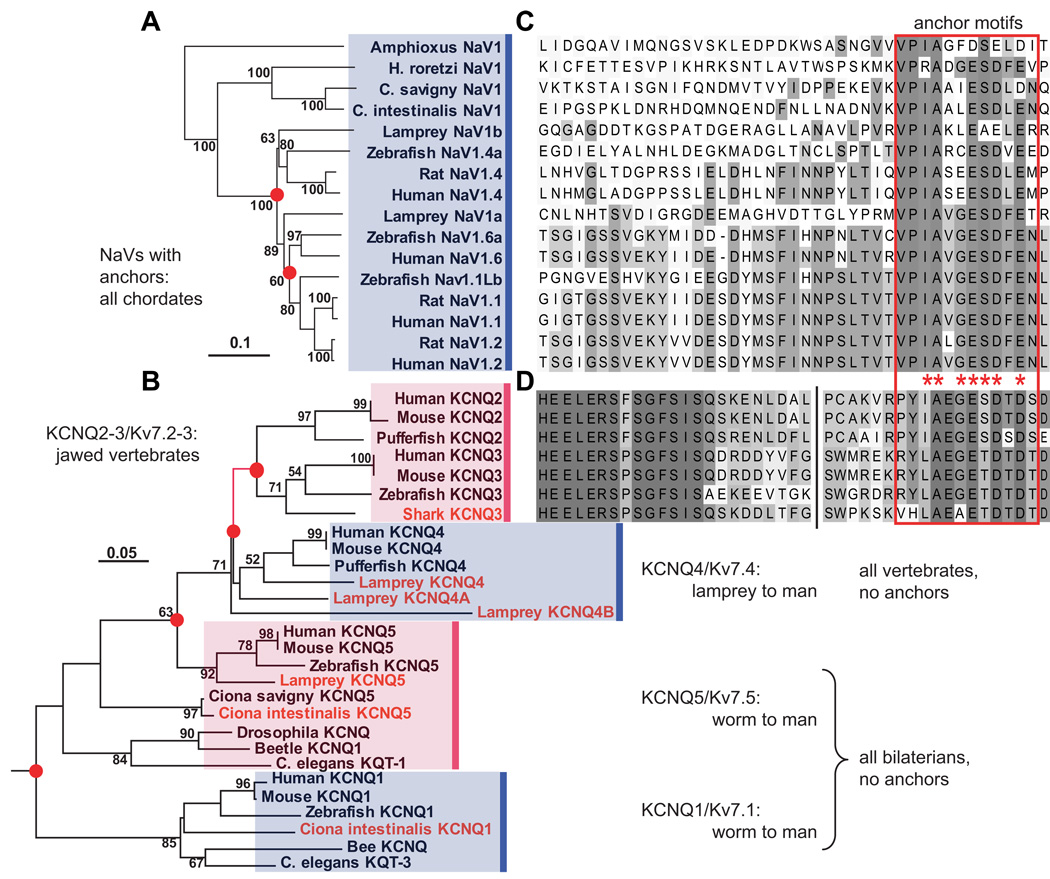

Figure 2. Phylogenetic analysis reveals that motifs for ankyrin-dependent axonal clustering evolved sequentially, first in chordates (NaV channels), then in jawed vertebrates (Kv7.2 and Kv7.3).

(A) Phylogram (minimal evolution) of NaV channels, showing that all vertebrate channels are derived from chordate NaV1. (B) Clustal alignment of NaV channel DII–DIII loop sequences, showing presence of anchor motifs in chordate NaV1 and all vertebrate channels. The anchor motifs are boxed (red). Shading indicates each residue’s conservation within a set of 28 chordate and non-chordate (not shown) aligned NaV sequences: bins represent ≤10, 11–20, 21–30, 31–45, 46–60, and 61–100 % conservation. (C) Phylogeny of KCNQ channels, based on analysis of derived amino acid sequences encoded on exons 5–7. Novel genes identified or cloned (see [12]) are shown in red. The branch marking the inferred first appearance of the KCNQ2/3 anchor motif is shown in red. (D) Alignment of KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 C-terminal intracellular sequences near the anchor motifs. Break (vertical black line) indicates location of 5–8 omitted, poorly conserved residues. The derived Kv7.2/Kv7.3 anchor motif sequences (red boxed region) are similar but non-identical to those of chordate NaV genes. Otherwise no similarity to the NaV DII–DIII loop sequence shown in B is present. Shading indicates conservation within the 7 KCNQ sequences aligned: shades represent ≤15, 15–30, 31–45, 46–60, 61–75, 76–90, and 91–100% conservation. In A and C, nodes are labeled with bootstrap values (>50%), nodes associated with gene duplications have red dots, and scale bars indicate substitutions per residue. After [12].

4.4. Kv7 channel function in the AIS

AP initiation by NaV channels in the AIS has recently been demonstrated through studies using direct patch clamp recordings from the axon [65, 66]. Because Kv7 currents are expected to be much smaller and are susceptible to rundown by dialysis of intracellular PIP2, recording their activity in the axon is especially challenging. Nonetheless, recent studies using extracellular perfusion of blockers, intracellular perfusion of ankyrin-binding mimetic peptide, and computational modeling have supported the hypothesis that the Kv7.2/Kv7.3 channels localized in the AIS are functional and modulate spike initiation and adaptation [67–69].

5. Voltage-gated NaV and KCNQ2/3 channel interaction with ankyrin isoforms arose sequentially during the evolution of early chordates and vertebrates

Pan et al. showed that ankyrin interaction motifs were absent from the NaV and Kv7 channels of fly, worm, and mollusks, but present in NaV and Kv7 channels cloned from zebrafish, birds, and mammals [20]. This was paradoxical, since NaV and Kv7 are distant homologues, and their other known homologous sequences (e.g., voltage sensors, pore modules) are found in all species. Additional investigation revealed, however, that ankyrin interaction was not present in the common ancestor gene of the NaV and Kv7 channels, but instead arose much more recently, during the early evolution of the phylum chordata.

5.1. The NaV channel anchor sequence arose in a common ancestor of extant chordates

Phylum chordata, which is distinguished by the presence of a dorsal nerve cord with an underlying supportive notochord or spinal column, among other features, includes the vertebrates and two closely related invertebrate groups, the cephalochordates and urochordates [70]. The genomes of a model cephalochordate (amphioxus, Branchiostoma floridae) and several urochordates (including the tunicate, Ciona intestinalis) have been cloned [71, 72], allowing the sequences of their NaV channels to be deduced [73, 74]. Although these genomes contain multiple NaV channel genes, one and only one gene per genome contains a sequence in the intracellular loop between domains II and III which is homologous to the ankyrin-interaction motif of mammalian NaV channels [75]. Phylogenetic analysis shows, further, that all vertebrate NaV channels are derived from the single cephalochordate/urochordate NaV channel that contains the motif [12, 74] (Fig. 2A, C). In cephalochordates and urochordates, the NaV channel anchor motif is contained on a single short exon, and thus an insertional event could have been the evolutionary mechanism leading to novel ankyrin interaction of the NaV channels, approximately 550 million years ago [12].

5.2. Neurons from sea lamprey, a primitive vertebrate, lack myelinated axons, but possess narrow initial segments bearing high concentrations of NaV channels

The vertebrates first evolved from chordate ancestors as organisms lacking bony internal skeletons, hinged jaws, and myelinated axons. The sea lamprey, Petromyzon marinus, is a model organism representative of such early jawless vertebrates [76]. Lamprey possesses at least 2 NaV genes; both bear ankyrin-interaction motifs [12]. Furthermore, although P. marinus axons lack myelin and rely on large diameters (like many invertebrates) to achieve higher conduction velocities [77], the initial segments of these axons are of narrow caliber, have high concentrations of NaV channels, and are the site of action potential initiation [78]. These findings are suggestive of the hypothesis that ankyrin interaction organizes the lamprey AIS and clusters NaV channels there.

5.3. The KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 anchor appear first in a common ancestor of jawed vertebrates, in association with myelin and saltatory conduction

Hill et. al. cloned and assembled Kv7 channel sequences from C. intestinalis, as well as from P. marinus and Callorhinchus milii (elephant shark, a model for earliest jawed vertebrates) [12]. Like other invertebrates, C. intestinalis possesses 2 KCNQ genes, encoding orthologues of the mammalian genes KCNQ1 and KCNQ5 (Fig. 2B). P. marinus KCNQ5 underwent gene duplication, resulting in one of more orthologues of mammalian KCNQ4. In C. milii, however, orthologues of all five mammalian KCNQ genes are present, as is the KCNQ2/KCNQ3 anchor motif (Fig. 2D). Thus, during the interval between the divergence of lamprey (~500 million years ago) and the origin of ancestral sharks (~430 million years ago) [79], three steps occurred. First, KCNQ4 underwent a duplication, producing a new gene. Second, this gene evolved the C-terminal domain which interacts with ankyrin. Third, the new gene duplicated again, generating the closely related genes KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 which are conserved in jawed vertebrates from shark to man (Fig. 2B–C).

5.4. The excitozone hypothesis

Clustering of NaV channels at high density by ankyrin is critical for vertebrate forms of neuronal polarity, for rapid and reliable initiation and conduction of action potentials by axons, and for cardiac excitability (see reviews by Rasband, Leterrier et al., and Mohler, this volume). Although the characterization of the molecular components present at the nodes and initial segments is incomplete, many of the key elements are evolutionarily ancient, including ankyrin [80], spectrin [81], and the NaV, Kv1, and Kv7 protein families. The evolution of this protein complex followed upon the emergence of new gene duplicates, some of which evolved novel capacity to interact as part of a new type of protein complex on the axon. It is striking that only the vertebrates and their closest evolutionary ancestors show evidence of ankyrin-based NaV and Kv7 clustering, and that the first steps in the evolutionary path were already present in the common chordate ancestor, a small-bodied invertebrate. Because axonal NaV channel clustering makes possible much more rapid action potential initiation and propagation, this evolutionary novelty was integral to the subsequent increase in chordate brain and body size and complexity. The excitozone hypothesis proposes that the clustering of NaV channels by ankyrin represents a key or “watershed” innovation [82] contributing to chordate divergence and success. This hypothesis may be tested by further studies of the deployment and function of ankyrin-clustered NaV channels and other associated proteins in basal chordate and vertebrate model organisms.

6. Conclusions

The Kv7 channels are evolutionarily ancient and widely expressed in neuronal and non-neuronal cells. The range of functions served by Kv7 tetrameric channels is wide, but in nervous systems, remains quite incompletely described. Vertebrate Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 subunits possess a C-terminal anchor motif, which (at least in mammals, but likely in all vertebrates) mediates interaction with ankyrin-G and clustering near NaV channels at nodes of Ranvier and AISs. KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 are the only known genes possessing NaV-like anchor motifs, and are relatively new genes which evolved 50–100 million years after NaV channels evolved their own anchors conferring the ability to be clustered by ankyrin. The evolutionary conservation of KCNQ2/KCNQ3 genes in vertebrates likely reflects the ability of co-clustered Kv7 channels to make action potential initiation and propagation by clustered NaV channels more robust and reliable.

Acknowledgements

I thank the members of my laboratory and other collaborators for their contribution to the work described. Grant support was provided by NIH R01 NS49119, NIH R21 NS55765, the Miles Family Fund, and the Human Frontiers Science Program.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Yu FH, Catterall WA. The VGL-chanome: a protein superfamily specialized for electrical signaling and ionic homeostasis. Sci STKE 2004. 2004:re15. doi: 10.1126/stke.2532004re15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hille B. Ionic channels of excitable membranes. 3rd. ed. Sunderland Mass.: Sinauer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai HC, Jan LY. The distribution and targeting of neuronal voltage-gated ion channels. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:548–562. doi: 10.1038/nrn1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jentsch TJ. Neuronal KCNQ potassium channels: physiology and role in disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2000;1:21–30. doi: 10.1038/35036198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Q, Curran ME, Splawski I, Burn TC, Millholland JM, VanRaay TJ, et al. Positional cloning of a novel potassium channel gene: KVLQT1 mutations cause cardiac arrhythmias. Nat Genet. 1996;12:17–23. doi: 10.1038/ng0196-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biervert C, Schroeder BC, Kubisch C, Berkovic SF, Propping P, Jentsch TJ, et al. A potassium channel mutation in neonatal human epilepsy. Science. 1998;279:403–406. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charlier C, Singh NA, Ryan SG, Lewis TB, Reus BE, Leach RJ, et al. A pore mutation in a novel KQT-like potassium channel gene in an idiopathic epilepsy family [see comments] Nat Genet. 1998;18:53–55. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh NA, Charlier C, Stauffer D, DuPont BR, Leach RJ, Melis R, et al. A novel potassium channel gene, KCNQ2, is mutated in an inherited epilepsy of newborns. Nat Genet. 1998;18:25–29. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh NA, Westenskow P, Charlier C, Pappas C, Leslie J, Dillon J, et al. KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 potassium channel genes in benign familial neonatal convulsions: expansion of the functional and mutation spectrum. Brain. 2003;126:2726–2737. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lerche C, Scherer CR, Seebohm G, Derst C, Wei AD, Busch AE, et al. Molecular cloning and functional expression of KCNQ5, a potassium channel subunit that may contribute to neuronal M-current diversity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:22395–22400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002378200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei AD, Butler A, Salkoff L. KCNQ-like potassium channels in Caenorhabditis elegans. Conserved properties and modulation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21337–21345. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502734200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill AS, Nishino A, Nakajo K, Zhang G, Fineman JR, Selzer ME, et al. Ion channel clustering at the axon initial segment and node of ranvier evolved sequentially in early chordates. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gutman GA, Chandy KG, Adelman JP, Aiyar J, Bayliss DA, Clapham DE, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XLI. Compendium of voltage-gated ion channels: potassium channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55:583–586. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.4.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu J, Yu W, Jan YN, Jan LY, Li M. Assembly of voltage-gated potassium channels. Conserved hydrophilic motifs determine subfamily-specific interactions between the alpha-subunits. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24761–24768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.24761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Long SB, Campbell EB, Mackinnon R. Crystal structure of a mammalian voltage-dependent Shaker family K+ channel. Science. 2005;309:897–903. doi: 10.1126/science.1116269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwake M, Athanasiadu D, Beimgraben C, Blanz J, Beck C, Jentsch TJ, et al. Structural determinants of M-type KCNQ (Kv7) K+ channel assembly. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3757–3766. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5017-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howard RJ, Clark KA, Holton JM, Minor DL., Jr Structural insight into KCNQ (Kv7) channel assembly and channelopathy. Neuron. 2007;53:663–675. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delmas P, Brown DA. Pathways modulating neural KCNQ/M (Kv7) potassium channels. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:850–862. doi: 10.1038/nrn1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernandez CC, Zaika O, Shapiro MS. A carboxy-terminal inter-helix linker as the site of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate action on Kv7 (M-type) K+ channels. J Gen Physiol. 2008;132:361–381. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan Z, Kao T, Horvath Z, Lemos J, Sul JY, Cranstoun SD, et al. A common ankyrin-G-based mechanism retains KCNQ and NaV channels at electrically active domains of the axon. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2599–2613. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4314-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanguinetti MC, Curran ME, Zou A, Shen J, Spector PS, Atkinson DL, et al. Coassembly of K(V)LQT1 and minK (IsK) proteins to form cardiac I(Ks) potassium channel. Nature. 1996;384:80–83. doi: 10.1038/384080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Splawski I, Shen J, Timothy KW, Lehmann MH, Priori S, Robinson JL, et al. Spectrum of mutations in long-QT syndrome genes. KVLQT1, HERG, SCN5A, KCNE1, and KCNE2. Circulation. 2000;102:1178–1185. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.10.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trussell L. Mutant ion channel in cochlear hair cells causes deafness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3786–3788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tzingounis AV, Heidenreich M, Kharkovets T, Spitzmaul G, Jensen HS, Nicoll RA, et al. The KCNQ5 potassium channel mediates a component of the afterhyperpolarization current in mouse hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107:10232–10237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004644107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suh BC, Hille B. PIP2 is a necessary cofactor for ion channel function: how and why? Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:175–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Preston P, Wartosch L, Gunzel D, Fromm M, Kongsuphol P, Ousingsawat J, et al. Disruption of the K+ channel beta-subunit KCNE3 reveals an important role in intestinal and tracheal Cl- transport. J Biol Chem. 285:7165–7175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.047829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiong Q, Gao Z, Wang W, Li M. Activation of Kv7 (KCNQ) voltage-gated potassium channels by synthetic compounds. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haitin Y, Attali B. The C-terminus of Kv7 channels: a multifunctional module. J Physiol. 2008;586:1803–1810. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.149187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schroeder BC, Kubisch C, Stein V, Jentsch TJ. Moderate loss of function of cyclic-AMP-modulated KCNQ2/KCNQ3 K channels causes epilepsy. Nature. 1998;396:687–690. doi: 10.1038/25367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kubisch C, Schroeder BC, Friedrich T, Lütjohann B, El-Amraoui A, Marlin S, et al. KCNQ4, a novel potassium channel expressed in sensory outer hair cells, is mutated in dominant deafness. Cell. 1999;96:437–446. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80556-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schroeder BC, Hechenberger M, Weinreich F, Kubisch C, Jentsch TJ. KCNQ5, a novel potassium channel broadly expressed in brain, mediates M-type currents. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:24089–24095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003245200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bal M, Zhang J, Zaika O, Hernandez CC, Shapiro MS. Homomeric and heteromeric assembly of KCNQ (Kv7) K+ channels assayed by total internal reflection fluorescence/fluorescence resonance energy transfer and patch clamp analysis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:30668–30676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805216200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gomez-Posada JC, Etxeberria A, Roura-Ferrer M, Areso P, Masin M, Murrell-Lagnado RD, et al. A pore residue of the KCNQ3 potassium M-channel subunit controls surface expression. J Neurosci. 30:9316–9323. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0851-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hadley JK, Passmore GM, Tatulian L, Al-Qatari M, Ye F, Wickenden AD, et al. Stoichiometry of expressed KCNQ2/KCNQ3 potassium channels and subunit composition of native ganglionic M channels deduced from block by tetraethylammonium. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5012–5019. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-05012.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kandel ER, Schwartz JH. Molecular biology of learning: modulation of transmitter release. Science. 1982;218:433–443. doi: 10.1126/science.6289442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown DA, Adams PR. Muscarinic suppression of a novel voltage-sensitive K+ current in a vertebrate neuron. Nature. 1980;283:673–676. doi: 10.1038/283673a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown D. M-currents: an update. Trends in neuroscience. 1988;11:294–299. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hodgkin AL, Huxley AF. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J Physiol. 1952;117:500–544. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chiu SY, Ritchie JM, Rogart RB, Stagg D. A quantitative description of membrane currents in rabbit myelinated nerve. J Physiol. 1979;292:149–166. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dubois JM. Potassium currents in the frog node of Ranvier. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1983;42:1–20. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(83)90002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dubois JM. Evidence for the existence of three types of potassium channels in the frog Ranvier node membrane. J Physiol. 1981;318:297–316. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roeper J, Schwarz JR. Heterogeneous distribution of fast and slow potassium channels in myelinated rat nerve fibres. J Physiol. 1989;416:93–110. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zimprich F, Ronen GM, Stogmann W, Baumgartner C, Stogmann E, Rett B, et al. Andreas Rett and benign familial neonatal convulsions revisited. Neurology. 2006;67:864–866. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000234066.46806.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ronen GM, Rosales TO, Connolly M, Anderson VE, Leppert M. Seizure characteristics in chromosome 20 benign familial neonatal convulsions. Neurology. 1993;43:1355–1360. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.7.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leppert M, Anderson VE, Quattlebaum T, Stauffer D, O'Connell P, Nakamura Y, et al. Benign familial neonatal convulsions linked to genetic markers on chromosome 20. Nature. 1989;337:647–648. doi: 10.1038/337647a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lewis TB, Leach RJ, Ward K, O'Connell P, Ryan SG. Genetic heterogeneity in benign familial neonatal convulsions: identification of a new locus on chromosome 8q. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;53:670–675. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cooper EC, Aldape KD, Abosch A, Barbaro NM, Berger MS, Peacock WS, et al. Colocalization and coassembly of two human brain M-type potassium channel subunits that are mutated in epilepsy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4914–4919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090092797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang H-S, Pan Z, Shi W, Brown BS, Wymore RS, Cohen IS, et al. KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 Potassium Channel Subunits: Molecular Correlates of the M-Channel. Science. 1998;282:1890–1893. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shapiro MS, Kaftan EJ, Roche JP, Cruzblanca H, Mackie K, Hille B. Muscarinic modulation of cloned KCNQ2/3 channels underlying the neuronal M current. Society for Neuroscience abstracts. 1999;25:1728. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-01710.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dedek K, Kunath B, Kananura C, Reuner U, Jentsch TJ, Steinlein OK. Myokymia and neonatal epilepsy caused by a mutation in the voltage sensor of the KCNQ2 K+ channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12272–12277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211431298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wuttke TV, Jurkat-Rott K, Paulus W, Garncarek M, Lehmann-Horn F, Lerche H. Peripheral nerve hyperexcitability due to dominant-negative KCNQ2 mutations. Neurology. 2007;69:2045–2053. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000275523.95103.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou X, Ma A, Liu X, Huang C, Zhang Y, Shi R, et al. Infantile seizures and other epileptic phenotypes in a Chinese family with a missense mutation of KCNQ2. Eur J Pediatr. 2006;165:691–695. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0157-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gutmann L, Libell D. When is myokymia neuromyotonia? Muscle Nerve. 2001;24:151–153. doi: 10.1002/1097-4598(200102)24:2<151::aid-mus10>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Browne DL, Gancher ST, Nutt JG, Brunt ER, Smith EA, Kramer P, et al. Episodic ataxia/myokymia syndrome is associated with point mutations in the human potassium channel gene, KCNA1 [see comments] Nat Genet. 1994;8:136–140. doi: 10.1038/ng1094-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Herson PS, Virk M, Rustay NR, Bond CT, Crabbe JC, Adelman JP, et al. A mouse model of episodic ataxia type-1. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:378–383. doi: 10.1038/nn1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Devaux JJ, Kleopa KA, Cooper EC, Scherer SS. KCNQ2 is a nodal K+ channel. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1236–1244. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4512-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schwarz JR, Glassmeier G, Cooper EC, Kao TC, Nodera H, Tabuena D, et al. KCNQ channels mediate IKs, a slow K+ current regulating excitability in the rat node of Ranvier. J Physiol. 2006;573:17–34. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.106815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Burke D, Kiernan MC, Bostock H. Excitability of human axons. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:1575–1585. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(01)00595-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kharkovets T, Dedek K, Maier H, Schweizer M, Khimich D, Nouvian R, et al. Mice with altered KCNQ4 K+ channels implicate sensory outer hair cells in human progressive deafness. Embo J. 2006;25:642–652. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rasmussen HB, Frokjaer-Jensen C, Jensen CS, Jensen HS, Jorgensen NK, Misonou H, et al. Requirement of subunit co-assembly and ankyrin-G for M-channel localization at the axon initial segment. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:953–963. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martire M, Castaldo P, D'Amico M, Preziosi P, Annunziato L, Taglialatela M. M channels containing KCNQ2 subunits modulate norepinephrine, aspartate, and GABA release from hippocampal nerve terminals. J Neurosci. 2004;24:592–597. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3143-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lawrence JJ, Saraga F, Churchill JF, Statland JM, Travis KE, Skinner FK, et al. Somatodendritic Kv7/KCNQ/M channels control interspike interval in hippocampal interneurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12325–12338. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3521-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhou D, Lambert S, Malen PL, Carpenter S, Boland LM, Bennett V. AnkyrinG is required for clustering of voltage-gated Na channels at axon initial segments and for normal action potential firing. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1295–1304. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.5.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chung HJ, Jan YN, Jan LY. Polarized axonal surface expression of neuronal KCNQ channels is mediated by multiple signals in the KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 C-terminal domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8870–8875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603376103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kole MH, Ilschner SU, Kampa BM, Williams SR, Ruben PC, Stuart GJ. Action potential generation requires a high sodium channel density in the axon initial segment. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:178–186. doi: 10.1038/nn2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shu Y, Duque A, Yu Y, Haider B, McCormick DA. Properties of action-potential initiation in neocortical pyramidal cells: evidence from whole cell axon recordings. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:746–760. doi: 10.1152/jn.00922.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yue C, Yaari Y. Axo-somatic and apical dendritic Kv7/M channels differentially regulate the intrinsic excitability of adult rat CA1 pyramidal cells. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:3480–3495. doi: 10.1152/jn.01333.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vervaeke K, Gu N, Agdestein C, Hu H, Storm JF. Kv7/KCNQ/M-channels in rat glutamatergic hippocampal axons and their role in regulation of excitability and transmitter release. J Physiol. 2006;576:235–256. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.111336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shah MM, Migliore M, Valencia I, Cooper EC, Brown DA. Functional significance of axonal Kv7 channels in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7869–7874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802805105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.De Robertis EM. Evo-devo: variations on ancestral themes. Cell. 2008;132:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Putnam NH, Butts T, Ferrier DE, Furlong RF, Hellsten U, Kawashima T, et al. The amphioxus genome and the evolution of the chordate karyotype. Nature. 2008;453:1064–1071. doi: 10.1038/nature06967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dehal P, Satou Y, Campbell RK, Chapman J, Degnan B, De Tomaso A, et al. The draft genome of Ciona intestinalis: insights into chordate and vertebrate origins. Science. 2002;298:2157–2167. doi: 10.1126/science.1080049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Okamura Y, Ono F, Okagaki R, Chong JA, Mandel G. Neural expression of a sodium channel gene requires cell-specific interactions. Neuron. 1994;13:937–948. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Okamura Y, Nishino A, Murata Y, Nakajo K, Iwasaki H, Ohtsuka Y, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the ascidian genome reveals novel insights into the molecular evolution of ion channel genes. Physiol Genomics. 2005;22:269–282. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00229.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Okamura Y. Evolution of chordate physiological functions viewed from ion channel genes. Kai-yo. 2005;41:61–70. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Grillner S. The motor infrastructure: from ion channels to neuronal networks. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:573–586. doi: 10.1038/nrn1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bullock TH, Moore JK, Fields RD. Evolution of myelin sheaths: both lamprey and hagfish lack myelin. Neurosci Lett. 1984;48:145–148. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(84)90010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Teravainen H, Rovainen CM. Fast and slow motoneurons to body muscle of the sea lamprey. J Neurophysiol. 1971;34:990–998. doi: 10.1152/jn.1971.34.6.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gess RW, Coates MI, Rubidge BS. A lamprey from the Devonian period of South Africa. Nature. 2006;443:981–984. doi: 10.1038/nature05150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cai X, Zhang Y. Molecular Evolution of the Ankyrin Gene Family. Mol Biol Evol. 2005 doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Baines AJ. Evolution of spectrin function in cytoskeletal and membrane networks. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:796–803. doi: 10.1042/BST0370796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dawkins R. The Evolution of Evolvability. In: Kumar S, Bentley PJ, editors. On Growth, Form and Computers. London: Elsevier Academic Press; 2003. pp. 239–255. [Google Scholar]