Abstract

A recently discovered enzyme system produces antibacterial hypothiocyanite (OSCN−) in the airway lumen by oxidizing the secreted precursor thiocyanate (SCN−). Airway epithelial cultures have been shown to secrete SCN− in a CFTR-dependent manner. Thus, reduced SCN− availability in the airway might contribute to the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis (CF), a disease caused by mutations in the CFTR gene and characterized by an airway host defense defect. We tested this hypothesis by analyzing the SCN− concentration in the nasal airway surface liquid (ASL) of CF patients and non-CF subjects, and in the tracheobronchial ASL of CFTR-ΔF508 homozygous pigs and control littermates. In the nasal ASL, the SCN− concentration was ~30-fold higher than in serum independently of the CFTR mutation status of the human subject. In the tracheobronchial ASL of CF pigs, the SCN− concentration was somewhat reduced. Among human subjects, SCN− concentrations in the ASL varied from person to person independent of CFTR expression, and CF patients with high SCN− levels had better lung function than those with low SCN− levels. Thus, although CFTR can contribute to SCN− transport, it is not indispensable for the high SCN− concentration in ASL. The correlation between lung function and SCN− concentration in CF patients may reflect a beneficial role for SCN−.

Keywords: thiocyanate, dual oxidase, lactoperoxidase, cystic fibrosis, airway surface liquid

INTRODUCTION

Most inhaled bacteria become entrapped in a mucus layer that covers the conducting airways. This mucus layer is constantly cleared from the healthy respiratory tract by the concerted movement of airway cilia. During the mucociliary clearance process, bacterial growth and survival is limited by the antimicrobial proteins of the airway surface liquid (ASL). Recent studies suggest that in addition to the antimicrobial proteins of airway secretions an oxidative host defense mechanism of airway epithelia may also contribute to the antibacterial activity in the ASL [1–3].

Airway epithelial cells express two plasma membrane-embedded cytochromes—Dual oxidase 1 (Duox1) and Duox2—that generate H2O2 on the extracellular side of the apical membrane [4–7]. Within the extracellular space, H2O2 is metabolized by the secretory protein lactoperoxidase (LPO) [8, 9], which uses H2O2 to oxidize the physiological ASL component thiocyanate (SCN−) to the potent antibacterial molecule hypothiocyanite (OSCN−). Cultured airway epithelia produce sufficient H2O2 to support OSCN− generation at levels toxic to bacteria [10–12]. Furthermore, inhibiting LPO activity in vivo hinders bacterial clearance from the lower airways [1].

Although the airway epithelium does not synthesize SCN−, the concentration of SCN− in the ASL (~460 μM) is far higher than that in the serum (5–50 μM) [3]. Cell-culture experiments indicated that SCN− is imported into the airway epithelium basolaterally, via the Na+-I− symporter NIS [13]. SCN− subsequently leaves the cells apically, through the CFTR anion channel [10, 11, 14], which is permeable to SCN− as well as to chloride (Cl−) and bicarbonate. Mutations in the gene encoding CFTR lead to cystic fibrosis (CF) disease, which in the airway is characterized by recurrent and chronic infections [15]. Notably, primary cultures of CF airway epithelia are defective for OSCN−-dependent bacterial killing, due to a reduction in SCN− secretion [10, 11]. These findings are consistent with the notion that insufficient SCN− secretion in CF airways might contribute to the pathogenesis of CF lung disease. However, the SCN− concentration in the ASL of CF patients has not been determined.

We used a recently developed porcine model of CF to evaluate the effect of CFTR inactivation on the SCN− concentration in tracheobronchial secretions. We also evaluated SCN− levels in the nasal secretions from CF patients and non-CF subjects. Contrary to our expectations, we found that the SCN− concentration was similar in the nasal secretions of CF and non-CF subjects, whereas a moderate reduction in SCN− concentration was detected in the tracheobronchial secretions of CF pigs as compared to control littermates. Furthermore, in humans CFTR-independent factors led to significant person-to-person variability in ASL SCN− concentrations, and CF patients with high SCN− levels exhibited better lung function than those with low SCN−.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human subjects

23 CF patients and 21 non-CF subjects participated in this study. Nasal ASL was collected from all participants. 14 CF subjects and 18 non-CF subjects also provided blood samples. Both CF and non-CF volunteers were non-smokers and experienced no symptoms of upper airway infection or allergic rhinitis during the three weeks prior to recruitment. For all recruited patients, the diagnosis of CF had been previously confirmed by genotyping. The pulmonary function of CF patients was evaluated based on the spirometric measurement of forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1). Spirometry was done according to the American Thoracic Society guidelines [16]. Additional subject information is summarized in Table 1. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Iowa.

Table 1.

Study-subject information.

| Characteristic | CF (n=23) | Non-CF (n=21) |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years (SD) | 34.7 (9.7) | 28.4 (7.1) |

| Age range in years | 23–60 | 21–52 |

| Gender ratio (M/F) | 14/9 | 13/8 |

| ΔF508 homozygous | 70% | 0 |

| ΔF508 compound heterozygous | 30% | 0 |

| Inpatients | 48% | 0 |

| Outpatients | 52% | 0 |

| Intravenous antibiotics | 36% | 0 |

| Oral antibiotics | 83% | 0 |

| Inhaled tobramycin and/or colistin | 61% | 0 |

| No antibiotics | 9% | 100% |

| P. aeruginosa in sputum | 74% | NDa |

not determined

CFTR mutant and control pigs

Production of heterozygous CFTR-ΔF508 pigs was previously reported [17]. These animals were intercrossed to generate homozygous CFTR-ΔF508 pigs and wild-type littermates. The lung phenotypes of homozygous CFTR-ΔF508 pigs and CFTR-null pigs [18–20] are indistinguishable (unpublished observation). Newborn pigs were genotyped immediately, and homozygous CFTR-ΔF508 pigs (n=6) and wild-type pigs (n=14) were used for this study within 12 hours of birth. This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Iowa.

Blood and ASL collection

Venous blood of human subjects was collected from an arm vein. Blood of CFTR-ΔF508 homozygous and wild-type pigs was collected under propofol anesthesia. Prior to the analysis of anion composition, the serum fraction was filtered (3 kDa cut-off Ultracel filter, Millipore) to remove the majority of serum proteins.

Nasal ASL was harvested from human subjects using microsampling probes (Olympus BC-402C) [21, 22]. Prior to sample collection, nostrils were kept closed with a diver’s clip for 5 min to minimize evaporation. The probes were then introduced deep into the nose and held gently to the nasal turbinates. After 30–60 seconds, probes were removed from the nose and placed onto filters in microcentrifuge tubes (Costar Spin-X filter). Undiluted ASL was recovered from the probes by centrifugation.

Lower airway secretions were collected from pigs under propofol anesthesia. The tracheas of pigs were surgically exposed and opened horizontally using electro-cauterization. Microsampling probes were introduced into the respiratory tract through the surgical opening, and were held gently to the surface of the trachea and bronchi at multiple points. Our initial experiments indicated that the volume of ASL collected from the lower airways was not always sufficient for analysis when dry probes were used, and that the efficiency of collection could be improved by pre-wetting the probes with 2 μL isosmotic mannitol solution containing 300 μM Evans blue dye. After ASL collection was completed, fluid was extracted from the probes by centrifugation, and the ASL content of the harvested fluid was calculated based on the extent to which Evans blue dye was diluted. The dilution factor was determined by measuring the optical density of the collected fluid at 600 nm, using NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer.

Ion-exchange chromatography

Ultrapure water was used to dilute the serum (4-fold) and ASL samples (50- and 100-fold) prior to measuring ion concentration using a Metrohm Advanced Ion Chromatography system (MIC-2, Metrohm USA, Inc.) and a Metrosep A Supp 5–150 column. The mobile phase was composed of 1 mM sodium carbonate and 3.2 mM sodium bicarbonate. Anions were detected based on changes in conductivity, and the conductivity detector was calibrated with standard solutions.

Bacterial killing assay

Well-differentiated primary cultures of human airway epithelia were obtained from the In Vitro Models and Cell Culture Core at the University of Iowa [23]. These cultures were maintained at air-liquid interface and incubated in the absence of antibiotics for 5 days prior to the bacterial killing assays. The bacterial killing activity of airway epithelial cultures was measured as previously described [10]. In brief, mid-log phase liquid cultures of Staphylococcus aureus (strain Xen8.1; Xenogen Corporation, Hokinton, MA) were pelleted and resuspended in PBS. Bacterial density was estimated by measuring optical density at 550 nm. Approximately 3,000 and 1,000 colony forming units (CFU) bacteria were inoculated onto the apical surface of airway epithelial cultures in PBS (60 μL inoculum/1 cm2 surface area) supplemented with LPO (7 μg/mL), SCN− (0–700 μM), and HEPES (10 mM, pH=6.6). Epithelial H2O2 production was maximized with the apical addition of ATP (100 μM) [6, 24, 25]. Following a 3-hour incubation at 37ºC, liquid was collected from the apical surface. Epithelial cultures were then lysed with 1% saponin in distilled water, and lysates were pooled with the previously collected apical fluid. The number of surviving bacteria was determined using quantitative liquid culture, as described previously [26].

Hypothiocyanite measurement

OSCN− production by primary airway epithelial cultures was assessed by detecting the oxidation of 2-nitro-5-thiobenzoate (TNB), as previously described [27]. Briefly, ATP (100 μM) stimulated airway epithelial cultures were incubated in the presence of LPO (7 μg/mL) and SCN− (0–700μM) in PBS (supplemented with 10 mM HEPES, pH=6.6) for 40 minutes at 37ºC. Following incubation, samples were removed and catalase added to remove excess H2O2. TNB (350 μM) was added to the samples, and the molar concentration of OSCN− was calculated based on the loss of absorbance at 412 nm (ε=14,000 M−1cm−1).

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as mean ± SEM. All statistical analyses were carried out using the GraphPad Prism 4.03 software. Ion concentrations in CF and non-CF samples were compared using two-tailed Mann-Whitney tests. Correlations between variables were studied using ordinary least-square linear regressions. Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) were calculated as measures of linear association. The equality of regression line slopes to zero was evaluated using two-tailed Student’s t test. Equality of regression curves was tested using an F-test.

RESULTS

SCN− concentrations in upper-airway secretions from CF patients and non-CF subjects are similar

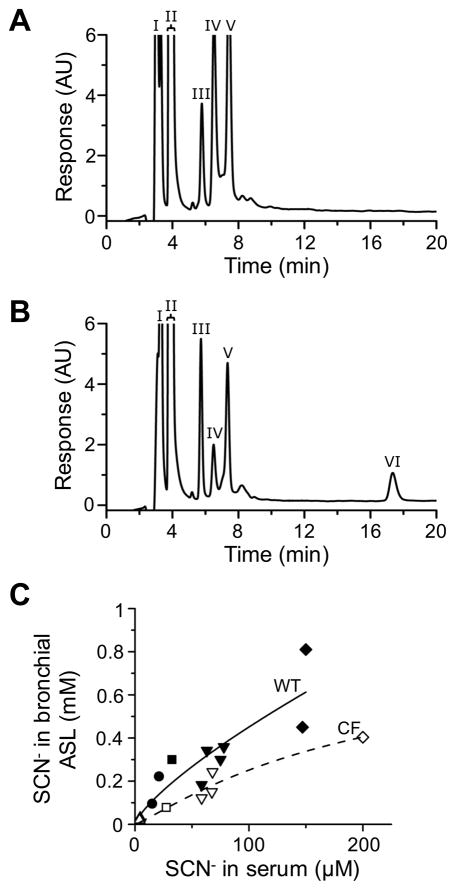

In order to evaluate the impact of CFTR deficiency on the SCN− concentration in nasal ASL, we collected upper airway secretions from CF and non-CF subjects and measured the SCN− content of the collected samples. We used a previously developed microsampling probe [21, 22] for the collection of nasal ASL. Samples were recovered from the probe by centrifugation and analyzed by anion-exchange chromatography. This method consistently detected anions in the ASL at the retention times characteristic of fluoride (F−), Cl−, nitrate (NO3−), hydrogen phosphate (HPO42−), sulfate (SO42−), and SCN− (Fig. 1A, calibration data are presented in the online data supplement Fig. S1). The identity of the SCN− peak was verified by the LPO-catalyzed oxidation of SCN− to OSCN− ex vivo (Fig. 1A inset).

Fig. 1. Anion composition analysis of nasal ASL in CF and non-CF subjects.

(A) A representative chromatogram of human ASL sample. ASL was collected from the nasal mucosa and diluted 50-fold prior to chromatography. The F− (I), Cl− (II), NO3− (III), HPO42− (IV), SO42− (V), and SCN− (VI) peaks are indicated with Roman numerals. The identity of the SCN− peak was verified by oxidizing the SCN− content of diluted ASL using an excess of LPO and H2O2 (inset). The detector response is shown in arbitrary units (AU). (B) SCN− concentrations in the nasal ASL of CF and non-CF subjects, as determined by ion-exchange chromatography (n=23 CF, 21 non-CF; Mann-Whitney test, p=0.89). (C) Correlation between SCN− concentrations in serum and nasal ASL of non-CF (▲) and CF (□) subjects. Each data point represents one subject. Solid and dotted lines indicate the best-fit linear regression lines to non-CF and CF data, respectively (non-CF: r=0.60, **p=0.0084; CF: r=0.97, ***p<0.0001). The slopes of the two regression lines are not significantly different (F-test, p=0.31).

The analysis of nasal ASL samples demonstrated that SCN− concentrations varied significantly from person to person in both subject groups (Fig. 1B). Moreover, the mean SCN− concentration in the nasal secretions of CF patients did not differ significantly from that in the nasal secretions of non-CF subjects (Fig. 1B). This was also the case for F−, HPO42−, and SO42− (data not shown). In contrast, the Cl− concentration was significantly elevated in the CF samples (Supplemental Fig. S2), in agreement with a recent study [28]. Similarly, the NO3− concentration tended to be elevated in the ASL of CF patients compared to that of non-CF subjects (Supplemental Fig. S3).

The similarity in the SCN− concentrations found in the upper airway secretions of CF and non-CF subjects indicated that the SCN− concentration in nasal ASL did not depend on CFTR activity. However, it remained possible that the SCN− concentration gradient between the ASL and serum was lower in CF patients than in non-CF subjects. Therefore, we determined the SCN− concentration not only in the ASL but also in the serum of CF and non-CF subjects. Our results revealed a linear correlation between the serum and ASL SCN− levels in both subject groups (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, our data showed that the SCN− concentration was approximately 30-fold higher in the ASL than in the serum, regardless of the mutation status of CFTR (Fig. 1C). These data indicate that the lack of CFTR activity did not reduce the SCN− concentration gradient between the serum and nasal ASL.

The SCN− concentration in tracheobronchial secretions of newborn pigs is partly CFTR dependent

In order to evaluate the SCN− concentration in tracheobronchial secretions, we used a recently developed porcine model of CF [17, 18]. This animal model has two unique advantages for our study. The first advantage is that homozygous CFTR-ΔF508 pigs can be studied immediately after birth, prior to the first incidence of airway infection. The lack of respiratory infection in the model system is important because inflammation itself could potentially alter ion transport across the airway mucosa. The second advantage of the pig model is related to the health risks of the ASL collection procedure. Our initial experiments in human subjects indicated that general anesthesia was necessary for the collection of undiluted tracheobronchial secretions free of contamination by saliva and local anesthetics (unpublished observation). The availability of CFTR mutant pigs make it possible to collect ASL from CF lower airways without exposing humans to risks associated with general anesthesia.

We collected ASL from the trachea and bronchi of homozygous CFTR-ΔF508 pigs and wild-type littermates under propofol anesthesia within 12 hours of birth (nasal ASL could not be collected due to the presence of amniotic debris in the snout). After ASL collection, blood samples were drawn, and anion concentrations were determined using anion-exchange chromatography. We found that both the ASL and serum of newborn pigs contained much less SCN− than did those of adult humans (<20 μM SCN− in ASL and <2 μM SCN− in serum; n=4 wild-type pigs). The low SCN− concentration in the serum of newborn pigs may have been related to the age of the animals, because older pigs had higher SCN− levels in the serum (7.2 ± 0.35 μM SCN−; 7-week old wild-type pigs, n=3). To replicate the wide range of serum SCN− concentrations found in humans, we administered intravenously various doses of SCN− to newborn pigs. 2 hours after SCN− injection, ASL and serum were collected and analyzed by ion-exchange chromatography. We found that the ASL SCN− concentration increased dramatically in pigs after intravenous SCN− administration (Fig. 2A and 2B). In both the homozygous CFTR-ΔF508 pigs and wild-type littermates, the SCN− concentration of the ASL was higher than that of the serum (Fig. 2C). However, this difference in SCN− levels between the ASL and serum was less pronounced in the CF group (Fig. 2C). These data indicate that SCN− concentration increased in the tracheobronchial secretions of SCN−-injected control pigs in a partly CFTR-dependent manner.

Fig. 2. SCN− secretion in the lower airways of CF and control pigs.

(A and B) Representative chromatograms of pig ASL samples. ASL samples were collected from the trachea and bronchi of (A) an untreated pig (representative of 4 newborn animals) and (B) a pig intravenously injected with 8 mg NaSCN/kg body weight (representative of 3 animals). The F− (I), Cl− (II), NO3− (III), HPO42− (IV), SO42− (V), and SCN− (VI) peaks are indicated with Roman numerals. Note that SCN− was not detected in the ASL of the untreated pig. The detector response is shown in arbitrary units (AU). (C) Relationship between SCN− concentrations in the serum and tracheobronchial ASL of homozygous CFTR-ΔF508 (open symbols) and wild-type (closed symbols) pigs 2 hours after intravenous injection of NaSCN at the following doses (in mg/kg body weight): 0.25 (up triangle), 1 (circle), 2 (square), 4 (down triangle), and 8 (diamond). Each data point represents one animal. Dotted (CF) and solid (wild-type, WT) lines were generated by fitting the CF and non-CF data to the Michaelis-Menten equation. The two curves are significantly different (F-test, *p=0.019).

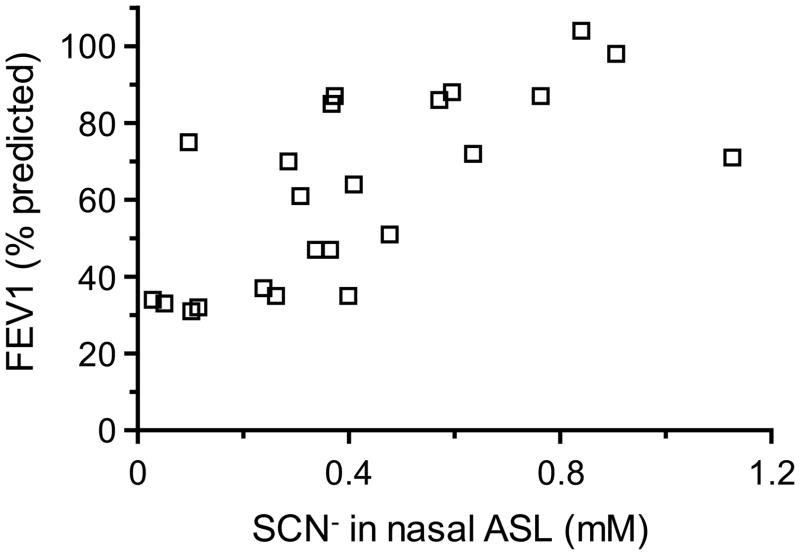

SCN− concentration in upper-airway secretions correlates with lung function in CF patients

Having determined that in both CF subjects and CFTR mutant pigs, the ASL SCN− concentration correlated strongly with serum SCN− levels (Fig. 1C and 2C), we next investigated whether additional correlations could be found between the ASL SCN− concentration and any other parameter that had been recorded for CF patients. The investigated parameters included age, gender, CFTR genotype, FEV1, body mass index, hospitalization status, the presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in sputum, the use and type of antibiotics, and the concentrations of F−, Cl−, NO3−, HPO42−, and SO42− in nasal ASL. Among these, only FEV1 correlated with the concentration of SCN− in nasal ASL (Fig. 3 and Supplemental Tables S2 and S3), and this correlation was positive, i.e. CF patients with high ASL SCN− concentrations exhibited better lung function than those with low SCN− (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. The relationship between nasal ASL SCN− concentration and FEV1 in CF patients.

Each data point represents the ASL SCN− concentration and FEV1 of one subject. The Pearson’s correlation test indicates association between the ASL SCN− concentration and FEV1 (r=0.7457, ***p<0.0001).

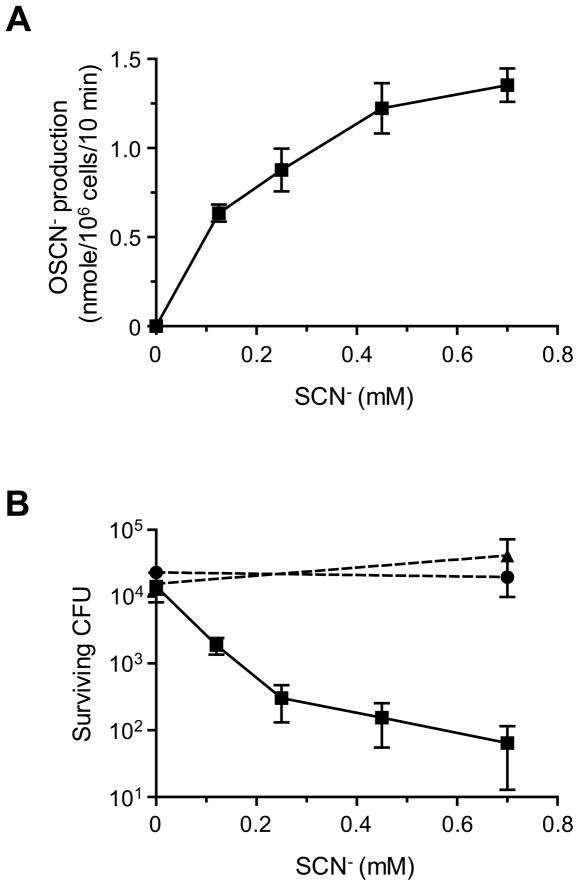

SCN− concentrations in the physiological range affect the antibacterial activity of airway epithelial cultures

Although the bactericidal activity of Duox/LPO enzymes of airway epithelia is known to depend strictly on the presence of SCN− [10–12], the SCN− dose dependence of the bacterial killing process has not been established. Therefore, we examined whether individual differences in ASL SCN− concentrations could affect OSCN− production and OSCN−-mediated host defense. Well-differentiated primary cultures of human airway epithelia were stimulated by apical ATP (100 μM) to maximize Duox-dependent H2O2 production [6, 24, 25], and the rate of OSCN− production was measured in the presence of LPO and various SCN− concentrations using the colorimetric substrate TNB. The tested SCN− concentrations (with the exception of zero) were selected from the physiological range in nasal ASL. The SCN−-dependence of OSCN− production was nearly hyperbolic with half-maximal reaction rate at 255 ± 83 μM SCN− (Fig. 4A), which agrees well with the in vitro established kinetic properties of LPO at pH 7 [29].

Fig. 4. SCN− concentration dependence of OSCN− production and bacterial killing by airway epithelia.

(A) OSCN− production by primary cultures of human airway epithelia in the presence of indicated SCN− concentrations, ATP (100 μM), and LPO (7 μg/ml) (n=3 for each data point). (B) Bacterial survival on the apical side of airway epithelia as a function of SCN− concentrations. The apical surface of human airway epithelial cultures was inoculated with 3,000 CFU S. aureus in the absence (squares) or presence of apically added H2O2 scavengers (5 mM glutathione, circles; 1,000 U/mL catalase, triangles). The apical buffer of all epithelial cultures also contained the indicated SCN− concentrations plus ATP (100 μM) and LPO (7 μg/ml); the number of surviving bacteria was evaluated after a 3-hour incubation using a quantitative bacterial culture method (n=5 for each data point).

Next, we investigated the effect of various SCN− concentrations on the ability of airway epithelia to kill a potential respiratory pathogen, S. aureus. Approximately 3,000 CFU of S. aureus were inoculated on the apical surface of human airway epithelial cultures in the presence of the physiological LPO concentration (7 μg/mL) and various concentrations of SCN− (Fig. 4B). Duox activity was maximized with the P2Y agonist ATP (100 μM, apical side). In negative control cultures, the apical buffer contained glutathione (5 mM) or catalase (1,000 U/mL) in addition to LPO, SCN−, and ATP. After a 3-hour incubation, we assessed the number of surviving bacteria by quantitative culture. Bacterial survival on the epithelial cultures mirrored the SCN− dose dependence of OSCN− production (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, both glutathione and catalase inhibited the antibacterial activity of airway epithelia, confirming that the SCN−-dependent bacterial killing required H2O2 production (Fig. 4B). When a smaller inoculum (1,000 CFU S. aureus) was tested, the SCN− dose dependence of bacterial killing was not altered (Supplemental Fig. S4). These data suggest that the observed person-to-person differences in ASL SCN− concentration were in a range that is relevant for the H2O2-dependent antibacterial activity of airway epithelia.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show that the concentration of the antibacterial precursor molecule SCN− is ~30-fold higher in the nasal ASL than in serum, independently of the CFTR mutation status of the human subject. In the tracheobronchial ASL of newborn CF pigs, the SCN− concentration also exceeded the serum SCN− level shortly after the intravenous injection of SCN−; however, the SCN− concentration gradient that developed between serum and ASL was somewhat greater in the wild-type pigs than in CF littermates. Our results also show that CF patients who had high SCN− concentrations in the ASL had better lung function than those with comparatively low SCN− concentrations. However, it will be necessary to carry out large-cohort longitudinal studies to unequivocally establish a correlation between ASL SCN− levels and lung function. We have also found that the person-to-person differences in ASL SCN− concentrations were in a range that is relevant for the antibacterial activity of airway epithelia in a cell-culture setting.

A previous study found ~460 μM SCN− in the tracheal secretions of non-CF adults [3]. We measured ~400 μM SCN− in the nasal secretions of both CF and non-CF adult subjects (Fig. 1B). Thus, the SCN− concentration gradient across the airway epithelium may be very similar in the nose and trachea of non-CF subjects. In contrast to the high SCN− level found in adults, a recent study has shown that the bronchoalveolar lavage from young non-CF and CF children contain barely detectable concentrations of SCN− [30]. Based on the assumption that the ASL was 100-fold diluted in these bronchoalveolar lavage samples, the SCN− concentration was estimated to be 28–56 μM in the ASL of young children [30]. Thus, the SCN− concentration in ASL may be substantially lower early in life than in adult subjects. This notion is also supported by our animal experiments that revealed much lower serum SCN− levels in newborn pigs than in 7-week old animals (i.e. <2 μM SCN− versus 7.2 ± 0.35 μM SCN−).

What factors may lead to an increase in serum SCN− concentration in healthy subjects? Animal cells do not synthesize SCN− [31], and thus the SCN− of body fluids is thought to be derived from vegetables and other plant foods. Cruciferous vegetables (broccoli, cabbage, etc.) are regarded as especially rich sources of SCN− [32]. In addition, when cyanide-containing food is ingested (e.g. cassava), SCN− is generated in the liver through the rhodanese-catalyzed detoxification of cyanide. Nevertheless, serum SCN− levels do not fluctuate with food intake because NIS-expressing organs with substantial fluid volumes (i.e. stomach and salivary glands) serve as SCN− reservoirs [31]. Thus, we speculate that long-term differences in the diet may account for at least some of the differences in serum SCN− concentrations among human subjects.

Our analysis of the nasal ASL samples showed that the Cl− concentration was elevated in the nasal secretions of CF subjects (Supplemental Fig. S2). A recent study also reported elevated Cl− in the nasal ASL of CF patients [28]; however, elevated Cl− levels were also found in the nasal ASL of non-CF patients with rhinitis [28]. Thus, increased Cl− concentration in the ASL may be a general sign of airway inflammation [28]. Our ASL analysis also revealed that the NO3− concentration tended to be elevated in the nasal secretions of CF subjects (Supplemental Fig. S3). Previous studies reported either increased [33–35] or normal NO3− concentrations [36, 37] in the airway secretions of CF subjects. In contrast, Thomas Kelley and colleagues measured reduced NO3− levels in the lung homogenates of CFTR mutant mice and found reduced iNOS expression in the airway epithelia of these animals [38]. Subsequent human subject studies reported reduced iNOS expression in the inflamed, but not in the non-inflamed, airway epithelium of CF patients [36, 37, 39]. A mechanism by which reduced iNOS expression might be accompanied by unaltered or increased NO3− concentration in the ASL of human subjects has been proposed by Anna Chapman and colleagues [36]. According to these authors, increased myeloperoxidase (MPO) and oxidant levels in the inflamed CF airway may enhance the metabolism of nitrogen monoxide to NO3− [36].

Our data revealed that CFTR was not indispensable for the generation of a SCN− concentration gradient between the nasal ASL and serum in adult human subjects. In contrast, the ex vivo-differentiated airway epithelium requires CFTR for SCN− secretion when the cells are maintained under standard culture condition [10, 11, 14]. These data suggest that the cultured airway epithelium lacks the CFTR-independent SCN− transporter of the airway mucosa. Interestingly, the anion transporter pendrin is capable of exporting SCN− from cells [14], and the expression of this transporter in the airway epithelium is upregulated dramatically by inflammatory cytokines both ex vivo and in vivo [14, 40, 41]. Therefore, pendrin is a strong candidate for mediating CFTR-independent SCN− secretion, especially in the inflamed airways.

SCN− concentration in upper-airway secretions correlated with lung function in CF patients. Although correlation does not necessarily imply a causal relationship between higher SCN− levels in ASL and better lung function, there are at least two mechanisms through which SCN− could favorably influence pulmonary function in CF patients. The first mechanism involves the intrinsic antibacterial activity of OSCN−. In the CF lung, several innate immune mechanisms are thought to be dysfunctional, including mucociliary clearance, antibacterial proteins and peptides, and neutrophil granulocytes [42]. In this context, low OSCN− production and the consequently low OSCN−-dependent bacterial killing activity might serve to undermine one more constituent of an already impaired antimicrobial arsenal. The second, but not mutually exclusive, mechanism is based on the antioxidant properties of SCN− [43–45]. During bacterial infection of the respiratory tract, activated neutrophil granulocytes are recruited into the airway lumen, where they produce hypochlorous acid (HOCl) by the combined effects of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase and the neutrophil granule protein MPO [30, 46]. Because HOCl is more toxic to eukaryotic cells than is OSCN− [47, 48], any reactions that increase the OSCN−:HOCl ratio will likely reduce oxidative damage of the host. SCN− can divert the net HOCl-generating activity of neutrophils towards OSCN− production in two ways [43–45]. First, SCN− inhibits the production of HOCl by competing with Cl− for MPO and H2O2. Second, SCN− reacts with HOCl, which leads to the consumption of HOCl and the production of OSCN−. As a result of these reactions, SCN− might benefit the CF airways not only because SCN− enhances Duox/LPO-dependent bacterial killing, but also because SCN− may prevent tissue damage inflicted by HOCl. Future studies are required to determine if either the antibacterial or antioxidant functions of SCN− support lung function in CF patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our gratitude to the CF patients and non-CF volunteers for their participation in this study and Olympus® (Tokyo) for providing the microsampling probes. We also thank Phil Karp for technical assistance with primary cell cultures, and Dr. John Engelhardt for helpful suggestions. This work was supported by grants from Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics (P&F project from R458-CR02 and BANFI07A0, to B.B.), the NHLBI (HL090830, to B.B.; HL91842, to M.J.W.), and the NIH (K23 HL075402 to L.D.). M.J.W. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator. Human cell cultures were provided by the In Vitro Models and Cell Culture Core at the University of Iowa, which is supported in part by funding from the NHLBI (HL51670), the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (R458-CR02 and ENGLH9850) and the NIDDK (DK54759).

Abbreviations

- ASL

airway surface liquid

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- CFU

colony forming unit

- Duox

Dual oxidase

- FEV1

forced expiratory volume in one second

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- HOCl

hypochlorous acid

- LPO

lactoperoxidase

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- NIS

Na+-I− symporter

- OSCN−

hypothiocyanite

- SCN−

thiocyanate

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gerson C, Sabater J, Scuri M, Torbati A, Coffey R, Abraham JW, Lauredo I, Forteza R, Wanner A, Salathe M, Abraham WM, Conner GE. The lactoperoxidase system functions in bacterial clearance of airways. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;22:665–671. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.22.6.3980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conner GE, Salathe M, Forteza R. Lactoperoxidase and hydrogen peroxide metabolism in the airway. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:S57–61. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2206018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wijkstrom-Frei C, El-Chemaly S, Ali-Rachedi R, Gerson C, Cobas MA, Forteza R, Salathe M, Conner GE. Lactoperoxidase and human airway host defense. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29:206–212. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0152OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geiszt M, Witta J, Baffi J, Lekstrom K, Leto TL. Dual oxidases represent novel hydrogen peroxide sources supporting mucosal surface host defense. FASEB J. 2003;17:1502–1504. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1104fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwarzer C, Machen TE, Illek B, Fischer H. NADPH oxidase-dependent acid production in airway epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:36454–36461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404983200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forteza R, Salathe M, Miot F, Forteza R, Conner GE. Regulated hydrogen peroxide production by Duox in human airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:462–469. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0302OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shao MX, Nadel JA. Dual oxidase 1-dependent MUC5AC mucin expression in cultured human airway epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:767–772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408932102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Chemaly S, Salathe M, Baier S, Conner GE, Forteza R. Hydrogen peroxide-scavenging properties of normal human airway secretions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:425–430. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200206-531OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salathe M, Holderby M, Forteza R, Abraham WM, Wanner A, Conner GE. Isolation and characterization of a peroxidase from the airway. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;17:97–105. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.1.2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moskwa P, Lorentzen D, Excoffon KJ, Zabner J, McCray PB, Jr, Nauseef WM, Dupuy C, Banfi B. A novel host defense system of airways is defective in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:174–183. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-1029OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conner GE, Wijkstrom-Frei C, Randell SH, Fernandez VE, Salathe M. The lactoperoxidase system links anion transport to host defense in cystic fibrosis. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:271–278. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rada B, Lekstrom K, Damian S, Dupuy C, Leto TL. The Pseudomonas toxin pyocyanin inhibits the dual oxidase-based antimicrobial system as it imposes oxidative stress on airway epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:4883–4893. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fragoso MA, Fernandez V, Forteza R, Randell SH, Salathe M, Conner GE. Transcellular thiocyanate transport by human airway epithelia. J Physiol. 2004;561:183–194. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.071548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pedemonte N, Caci E, Sondo E, Caputo A, Rhoden K, Pfeffer U, Di Candia M, Bandettini R, Ravazzolo R, Zegarra-Moran O, Galietta LJ. Thiocyanate transport in resting and IL-4-stimulated human bronchial epithelial cells: role of pendrin and anion channels. J Immunol. 2007;178:5144–5153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibson RL, Burns JL, Ramsey BW. Pathophysiology and management of pulmonary infections in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:918–951. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200304-505SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Thoracic Society. Standardization of Spirometry, 1994 Update. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1107–1136. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogers CS, Hao Y, Rokhlina T, Samuel M, Stoltz DA, Li Y, Petroff E, Vermeer DW, Kabel AC, Yan Z, Spate L, Wax D, Murphy CN, Rieke A, Whitworth K, Linville ML, Korte SW, Engelhardt JF, Welsh MJ, Prather RS. Production of CFTR-null and CFTR-DeltaF508 heterozygous pigs by adeno-associated virus-mediated gene targeting and somatic cell nuclear transfer. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1571–1577. doi: 10.1172/JCI34773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogers CS, Stoltz DA, Meyerholz DK, Ostedgaard LS, Rokhlina T, Taft PJ, Rogan MP, Pezzulo AA, Karp PH, Itani OA, Kabel AC, Wohlford-Lenane CL, Davis GJ, Hanfland RA, Smith TL, Samuel M, Wax D, Murphy CN, Rieke A, Whitworth K, Uc A, Starner TD, Brogden KA, Shilyansky J, McCray PBJ, Zabner J, Prather RS, Welsh MJ. Disruption of the CFTR gene produces a model of cystic fibrosis in newborn pigs. Science. 2008;321:1837–1841. doi: 10.1126/science.1163600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyerholz DK, Stoltz DA, Namati E, Ramachandran S, Pezzulo AA, Smith AR, Rector MV, Suter MJ, Kao S, McLennan G, Tearney GJ, Zabner J, McCray JPB, Welsh MJ. Loss of CFTR function produces abnormalities in tracheal development in neonatal pigs and young children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:1251–1261. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0643OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stoltz DA, Meyerholz DK, Pezzulo AA, Ramachandran S, Rogan MP, Davis GJ, Hanfland RA, Wohlford-Lenane C, Dohrn CL, Bartlett JA, Nelson GAt, Chang EH, Taft PJ, Ludwig PS, Estin M, Hornick EE, Launspach JL, Samuel M, Rokhlina T, Karp PH, Ostedgaard LS, Uc A, Starner TD, Horswill AR, Brogden KA, Prather RS, Richter SS, Shilyansky J, McCray PBJ, Zabner J, Welsh MJ. Cystic fibrosis pigs develop lung disease and exhibit defective bacterial eradication at birth. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:29ra31. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Durairaj L, Neelakantan S, Launspach J, Watt JL, Allaman MM, Kearney WR, Veng-Pedersen P, Zabner J. Bronchoscopic assessment of airway retention time of aerosolized xylitol. Respir Res. 2006;7:27. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamazaki K, Ogura S, Ishizaka A, Oh-hara T, Nishimura M. Bronchoscopic microsampling method for measuring drug concentration in epithelial lining fluid. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1304–1307. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200301-111OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zabner J, Scheetz TE, Almabrazi HG, Casavant TL, Huang J, Keshavjee S, McCray PBJ. CFTR DeltaF508 mutation has minimal effect on the gene expression profile of differentiated human airway epithelia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L545–553. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00065.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wesley UV, Bove PF, Hristova M, McCarthy S, van der Vliet A. Airway epithelial cell migration and wound repair by ATP-mediated activation of dual oxidase 1. J Biol Chem. 2007;5:3213–3220. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606533200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boots AW, Hristova M, Kasahara DI, Haenen GR, Bast A, van der Vliet A. ATP-mediated activation of the NADPH oxidase DUOX1 mediates airway epithelial responses to bacterial stimuli. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:17858–17867. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809761200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rada BK, Geiszt M, Kaldi K, Timar C, Ligeti E. Dual role of phagocytic NADPH oxidase in bacterial killing. Blood. 2004;104:2947–2953. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aune TM, Thomas EL. Accumulation of hypothiocyanite ion during peroxidase-catalyzed oxidation of thiocyanate ion. Eur J Biochem. 1977;80:209–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vanthanouvong V, Kozlova I, Johannesson M, Naas E, Nordvall SL, Dragomir A, Roomans GM. Composition of nasal airway surface liquid in cystic fibrosis and other airway diseases determined by X-ray microanalysis. Microsc Res Tech. 2006;69:271–276. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pruitt KM, Mansson-Rahemtulla B, Baldone DC, Rahemtulla F. Steady-state kinetics of thiocyanate oxidation catalyzed by human salivary peroxidase. Biochemistry. 1988;27:240–245. doi: 10.1021/bi00401a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomson E, Brennan S, Senthilmohan R, Gangell CL, Chapman AL, Sly PD, Kettle AJ. Identifying peroxidases and their oxidants in the early pathology of cystic fibrosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49:1354–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Funderburk CF, Van Middlesworth L. Thiocyanate physiologically present in fed and fasted rats. Am J Physiol. 1968;215:147–151. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1968.215.1.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murray S, Lake BG, Gray S, Edwards AJ, Springall C, Bowey EA, Williamson G, Boobis AR, Gooderham NJ. Effect of cruciferous vegetable consumption on heterocyclic aromatic amine metabolism in man. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:1413–1420. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.9.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grasemann H, Ioannidis I, Tomkiewicz RP, de Groot H, Rubin BK, Ratjen F. Nitric oxide metabolites in cystic fibrosis lung disease. Arch Dis Child. 1998;78:49–53. doi: 10.1136/adc.78.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones KL, Hegab AH, Hillman BC, Simpson KL, Jinkins PA, Grisham MB, Owens MW, Sato E, Robbins RA. Elevation of nitrotyrosine and nitrate concentrations in cystic fibrosis sputum. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2000;30:79–85. doi: 10.1002/1099-0496(200008)30:2<79::aid-ppul1>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Linnane SJ, Keatings VM, Costello CM, Moynihan JB, O’Connor CM, Fitzgerald MX, McLoughlin P. Total sputum nitrate plus nitrite is raised during acute pulmonary infection in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:207–212. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.1.9707096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chapman AL, Morrissey BM, Vasu VT, Juarez MM, Houghton JS, Li CS, Cross CE, Eiserich JP. Myeloperoxidase-dependent oxidative metabolism of nitric oxide in the cystic fibrosis airway. J Cyst Fibros. 2010;9:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wooldridge JL, Deutsch GH, Sontag MK, Osberg I, Chase DR, Silkoff PE, Wagener JS, Abman SH, Accurso FJ. NO pathway in CF and non-CF children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;37:338–350. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelley TJ, Drumm ML. Inducible nitric oxide synthase expression is reduced in cystic fibrosis murine and human airway epithelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1200–1207. doi: 10.1172/JCI2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morrissey BM, Schilling K, Weil JV, Silkoff PE, Rodman DM. Nitric oxide and protein nitration in the cystic fibrosis airway. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;406:33–39. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00427-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakagami Y, Favoreto SJ, Zhen G, Park SW, Nguyenvu LT, Kuperman DA, Dolganov GM, Huang X, Boushey HA, Avila PC, Erle DJ. The epithelial anion transporter pendrin is induced by allergy and rhinovirus infection, regulates airway surface liquid, and increases airway reactivity and inflammation in an asthma model. J Immunol. 2008;181:2203–2210. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakao I, Kanaji S, Ohta S, Matsushita H, Arima K, Yuyama N, Yamaya M, Nakayama K, Kubo H, Watanabe M, Sagara H, Sugiyama K, Tanaka H, Toda S, Hayashi H, Inoue H, Hoshino T, Shiraki A, Inoue M, Suzuki K, Aizawa H, Okinami S, Nagai H, Hasegawa M, Fukuda T, Green ED, Izuhara K. Identification of pendrin as a common mediator for mucus production in bronchial asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Immunol. 2008;180:6262–6269. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Döring G, Gulbins E. Cystic fibrosis and innate immunity: how chloride channel mutations provoke lung disease. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:208–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu Y, Szép S, Lu Z. The antioxidant role of thiocyanate in the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis and other inflammation-related diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:20515–20519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911412106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Dalen CJ, Whitehouse MW, Winterbourn CC, Kettle AJ. Thiocyanate and chloride as competing substrates for myeloperoxidase. Biochem J. 1997;327(Pt 2):487–492. doi: 10.1042/bj3270487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ashby MT, Carlson AC, Scott MJ. Redox buffering of hypochlorous acid by thiocyanate in physiologic fluids. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15976–15977. doi: 10.1021/ja0438361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van der Vliet A. NADPH oxidases in lung biology and pathology: host defense enzymes, and more. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:938–955. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang JG, Mahmud SA, Nguyen J, Slungaard A. Thiocyanate-dependent induction of endothelial cell adhesion molecule expression by phagocyte peroxidases: a novel HOSCN-specific oxidant mechanism to amplify inflammation. J Immunol. 2006;177:8714–8722. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang JG, Slungaard A. Role of eosinophil peroxidase in host defense and disease pathology. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2006;445:256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.