Abstract

Aim

The extracellular matrix is a complex system that regulates cell function within a tissue. The antioxidant enzyme extracellular superoxide dismutase (EC-SOD) is bound to the matrix and previous studies show that a lack of EC-SOD results in increased cardiac injury, fibrosis, and loss of cardiac function. This study tests the hypothesis that EC-SOD protects against cardiac fibrosis mechanistically by limiting oxidative stress and oxidant-induced shedding of syndecan-1 in the extracellular matrix.

Methods

Wild type and EC-SOD null mice were treated with a single dose of doxorubicin, 15 mg/kg, and evaluated on day 15. Serum and left ventricle tissue were collected for biochemical assays, including western blot, mRNA expression, and immunohistochemical staining for syndecan-1.

Results

The loss of EC-SOD and doxorubicin-induced oxidative injury lead to increases in shed syndecan-1 in the serum, which originates from the endothelium of the vasculature. The shed syndecan-1 ectodomain induces proliferation of primary mouse cardiac fibroblasts.

Conclusions

This study suggests that one mechanism through which EC-SOD protects the heart against cardiac fibrosis is by preventing oxidative shedding of cardiovascular syndecan-1 and its subsequent induction of fibroblast proliferation. This study provides potential new targets for understanding and altering fibrosis progression in the heart.

Keywords: Extracellular Superoxide dismutase, doxorubicin, syndecan-1, fibrosis

Introduction

Cardiac remodeling and fibrosis can occur after oxidant and ischemic insults to the heart. Extracellular superoxide dismutase (EC-SOD) is an antioxidant enzyme that scavenges superoxide free radicals from the extracellular environment and has been implicated in cardiovascular disease[1-4]. It is intricately associated with heparan sulfate and collagen in the extracellular matrix (ECM)[5-7] and is highly expressed in the lung and vasculature system[7, 8]. EC-SOD has a role in the prevention of tissue injuries, such as after Doxorubicin-induced oxidative injury[9], myocardial infarction[1, 4] and pressure overload[10]. The specific mechanisms through which EC-SOD mediates the injury response are unknown. However, binding of EC-SOD to the ECM of the heart and arteries is thought to be critical for its cardio-protective effects. This occurs through the heparin/matrix binding domain of EC-SOD. Several studies show that an EC-SOD gene variant (ECSODR213G) results in a decrease in binding affinity of EC-SOD for the tissue matrix and leads to an increased risk of cardiovascular and ischemic heart disease[3, 11, 12].

Syndecan-1 is a heparan sulfate proteoglycan that is important in binding EC-SOD, growth factors and cytokines in the ECM[13, 14]. As a membrane bound species, syndecan-1 regulates cell adhesions and signaling[14] and over-expression of syndecan-1 in the heart protects against ventricle enlargement and loss of cardiac function[15]. It can be proteolytically[16] or oxidatively shed[17, 18] from cell surfaces, which results in release of the extracellular domain of the protein. The functions of the soluble ectodomain are less clear.

Previous studies show that EC-SOD protects against oxidative stress in the heart by limiting fibrosis, extracellular oxidative stress, myocardial apoptosis, and loss of cardiac function in a model of doxorubicin-induced injury[9]. Notably, it has been shown in pulmonary fibrosis that EC-SOD prevents oxidant-induced shedding of syndecan-1 in the lung from oxidative shedding and that the shed syndecan-1 ectodomain gains pro-fibrotic functions[17, 18]. This led to the hypothesis that one mechanism through which EC-SOD may mediate cardiac fibrosis by protecting syndecan-1 in the cardiovascular system from oxidative shedding. To investigate this, a mouse model of doxorubicin-induced cardiac fibrosis in wild type and EC-SOD null (KO) mice was utilized. EC-SOD KO mice have higher levels of systemic oxidative stress and provide a model to better understand the role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of tissue fibrosis. Doxorubicin is an agent commonly included in chemotherapy regimens and can cause oxidant-mediated non-ischemic cardiomyopathy with subsequent heart failure[19, 20]. Primary mouse cardiac fibroblasts were treated with the syndecan-1 ectodomain to evaluate how shed syndecan-1 may participate in the pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis.

Methods

Animal Treatments

The University of Pittsburgh IACUC approved all animal protocols and the investigation conforms to the National Institutes of Health Guidelines. Female wild type C57BL/6 and EC-SOD-null mice (EC-SOD KO)[21] were treated with a single intraperitoneal injection of saline or 15 mg/kg doxorubicin (Adriamycin©, Bedford Laboratories, Bedford, OH). Animals were euthanized for the collection of serum and hearts. The left ventricle with intraventricular septum was dissected out, and sectioned for protein homogenization and RNA isolation (see subsequent sections for details).

Blood Analysis

Blood samples were processed by incubation at room temperature for 1 hour followed by 2 hours on ice and centrifuged at 20,000g. Serum concentrations were determined by the Bradford Protein Assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and analyzed by western blot analysis for ECSOD and syndecan-1.

Tissue Homogenization

Dissected left ventricular tissue was homogenized on ice in KBr buffer (50mmol/L potassium phosphate, pH7.4, 0.3 mol/L potassium bromide) with protease inhibitors (10 μmol/L Dichloro-isocoumarin, 3mM EDTA, and 100 μmol/L E-64, Sigma). Samples were centrifuged and the soluble protein fraction was collected. CHAPS detergent buffer (50mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH7.4, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 10 mmol/L CHAPS) with the same protease inhibitors was used to collect the membrane protein fraction from the remaining tissue pellet. CHAPS samples were rotated for 2 hours at 4°C, followed by sonication and centrifugation. The supernatants were collected and all samples were stored at -80°C until use.

Western Blotting

Serum (10μg protein) and LV homogenate samples (40μg protein) were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes at 500 mA for 90 minutes and blocked overnight in 5% dry milk in PBS-tween at 4°C. Membranes were probed for syndecan-1 ectodomain (rat anti-mouse syndecan-1 (281.2), BD Biosciences) followed by peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). ECL chemiluminescence reagents were used for band visualization (ECL-plus, GE Healthcare). Ponceau red staining and β-actin were used to normalize protein loading. Images were captured with a Gel Logic 2200 system (Kodak) for densitometry analysis of bands. Protein specific bands were normalized to the protein loading staining or β-actin. Data are reported as mean normalized net intensities ± SEM.

Quantitative Real Time RT-PCR

RNA was isolated from small sections of left ventricle tissue for each mouse using a Qiagen RNeasy Kit. Real time reverse transcriptase PCR was used to quantify mRNA expression (ddCt relative quantitation) of syndecan-1 in left ventricular tissue sections from wild type and EC-SOD KO mice at day 15 after doxorubicin treatment. A 7300 Applied Biosystems PCR System and primer/probe set (Syndecan-1 Mm00448918_m1 Sdc1; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) were used according to the manufacturers protocols and as previously described[17, 22]. Sequence Detection Software Version 1.4 (Applied Biosystems) was used to analyze the data based on the crossing threshold and to obtain mRNA relative expression quantities for each sample. The ddCt relative expression for each group were averaged and normalized to one treatment group for the determination of percent relative expression. Data are reported as percent expression (ddCt), n=5 samples per group, per gene. GAPDH expression was used as the endogenous control.

Syndecan-1 Immunohistochemical Staining and Pathological Scoring

Select heart tissues were perfused and fixed in 10% buffered formalin overnight at 4°C for paraffin embedding. Tissues were then sectioned at 4μm, placed on slides and heated at 60°C overnight, and deparaffinized in xylene. The sections were then rehydrated in an ethanol series and stained for syndecan-1 by traditional streptavidin-biotin immunohistochemical staining. Briefly, the antibodies used were an anti-mouse syndecan-1 ectodomain antibody (281.2, BD Biosciences) and an anti-rat biotin-conjugated IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch). The Vectastain ABC Elite Kit was used, including the Avidin DH and biotinylated HRP reagents (Vector, Burlingame, CA) and the Vector NovaRed Substrate. After staining, slides were dehydrated in an ethanol series, and cleared with xylene. Sections were cover-slipped with Permount (Sigma). Images were collected using bright field microscopy at 40X magnification. A scoring system was developed to assess the presence of vascular syndecan-1. The left ventricle of a cardiac section was identified and the high power field moved across the section until 20 vessels were scored. Sections were scored for 3 mice per group and 2 sections per mouse. Vessels were assigned a numerical value based on their staining intensity: 0 = no staining, 1 = moderate staining, 2 = strong staining. Scores were totaled and divided by 20 total vessels. See the “Statistical Analysis” section for data analysis details.

Primary Mouse Cardiac Fibroblast Cultures

Primary mouse cardiac fibroblasts were isolated from 8 week old C57BL/6 mice by a modified method[23, 24]. Ventricular tissue was dissected from the atria of each heart, minced into pieces, and placed in dissociation buffer containing 0.1mg/ml collagenase in sterile HBSS, 3mM CaCl2, and 0.1% trypsin in EDTA-free DMEM (Invitrogen). The cell suspension was incubated for 10 minutes at 37 C, spun down and resuspended in dissociation buffer for 2 more incubation cycles. The cells were placed in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum and standard antibiotics. The collected cells were plated onto 100mm3 dishes for 3 hours. The media was then removed, non-adherent cells were washed off and new media was applied. Fibroblasts, at passage 2-4, were plated onto 96-well plates for the proliferation assay and 24-well plates for TGF-β1 analysis. Cells were exposed to serum free media for 24 hours followed by treatment with 1, 2 or 3μg/ml human syndecan-1 ectodomain protein (a gift from Dr. Alan Rapraeger, University of Wisconsin) for 24 hours. Proliferation was assayed using the Cell-Titer 96-AQ Assay (Promega, Madison, WI) and 24-well supernatants were collected and assayed for total and active TGF-β1 by ELISA (R&D Biosciences), as previously described[17].

Statistical Analysis

Graphpad Prism Software was used for statistical analysis (Graphpad, San Diego, CA). Mean densitometry for western blotting and other quantitative data are reported as mean ± SEM and were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA for the comparison of the wild type and EC-SOD KO mouse strains. Bonferroni post-tests were also performed for all ANOVA data. Vasculature syndecan-1 scoring data was analyzed by non-parametric ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis Test with a Dunn's post-test. P-values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Lack of EC-SOD leads to cardiac failure and syndecan-1 shedding

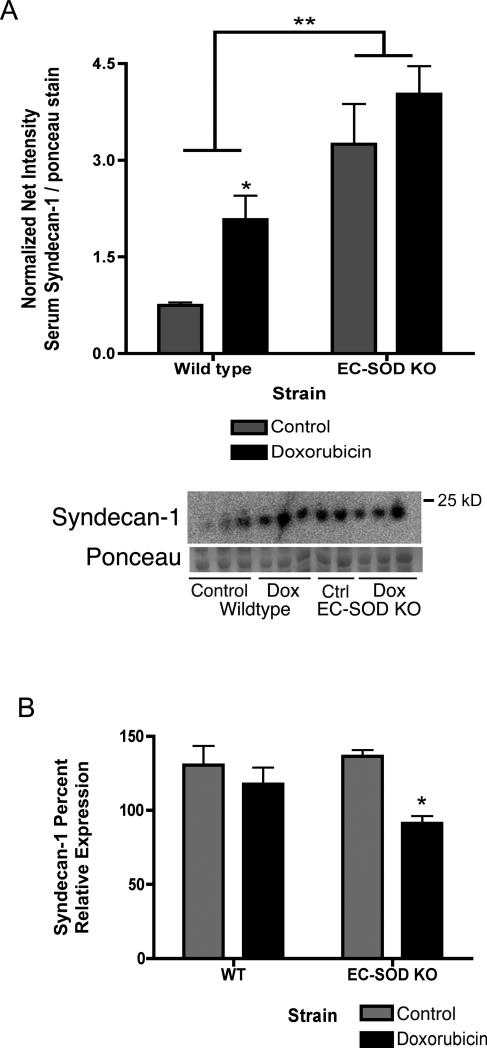

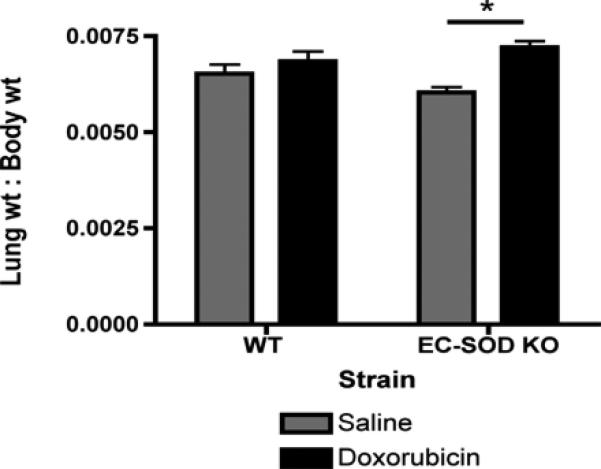

EC-SOD KO mice develop significantly more cardiac fibrosis and loss of cardiac function (ejection fraction) after doxorubicin treatment compared to wild-type mice[9]. EC-SOD KO mice treated with doxorubicin also have a significant increase in lung: body weight ratio, EC-SOD KO saline 0.0060 ±0.0003 vs. doxorubicin 0.0072 ±0.0004 (Figure 1, *p<0.05). Syndecan-1 is a major component of the extracellular matrix and anchors EC-SOD to cell surfaces. Serum levels of shed syndecan-1 ectodomain increase in WT mice after doxorubicin treatment (Figure 2A, *p<0.05). Notably, control-treated EC-SOD KO mice start out with markedly higher levels of syndecan-1 in the sera compared to control wild-type mice. Syndecan-1 levels in the serum trend to increase after doxorubicin treatment of EC-SOD KO mice, however, this increase is not statistically significant (Figure 2A, *p<0.05). In the left ventricle, syndecan-1 mRNA expression significantly decreases in EC-SOD KO mice after doxorubicin by day 15 (Figure 2B, *p<0.05). No baseline differences are seen in syndecan-1 expression in the left ventricles of control-treated wild type and EC-SOD KO mice.

Figure 1.

Loss of EC-SOD results in an increase in lung: body weight ratio after doxorubicin treatment, suggesting pulmonary congestion and cardiac dysfunction. Data are reported as mean lung: body weight ratio ± SEM. n=7, *p<0.05.

Figure 2.

Loss of EC-SOD and oxidative stress cause increased shedding of syndecan-1 into the serum and decreased mRNA expression in the left ventricle. Syndecan-1 was detected by western blot in serum samples from control- or doxorubicin-treated wild type and ECSOD KO mice. A) Syndecan-1 shedding into the serum. Data reported as net intensity of syndecan-1 normalized to ponceau red staining, mean ± SEM, n=3. *p<0.05 compared to control WT; **p<0.05 EC-SOD KO strain compared to wild type. 2-way anova statistical analysis was completed, with a Bonferroni post-test. B) Syndecan-1 mRNA expression in left ventricle tissue. Data reported as mean percent relative ddCt expression ± SEM (normalized to GAPDH), n=3-4. *p<0.05 compared to control-treated EC-SOD KO mice.

Loss of Vascular Syndecan-1 with Oxidative Stress

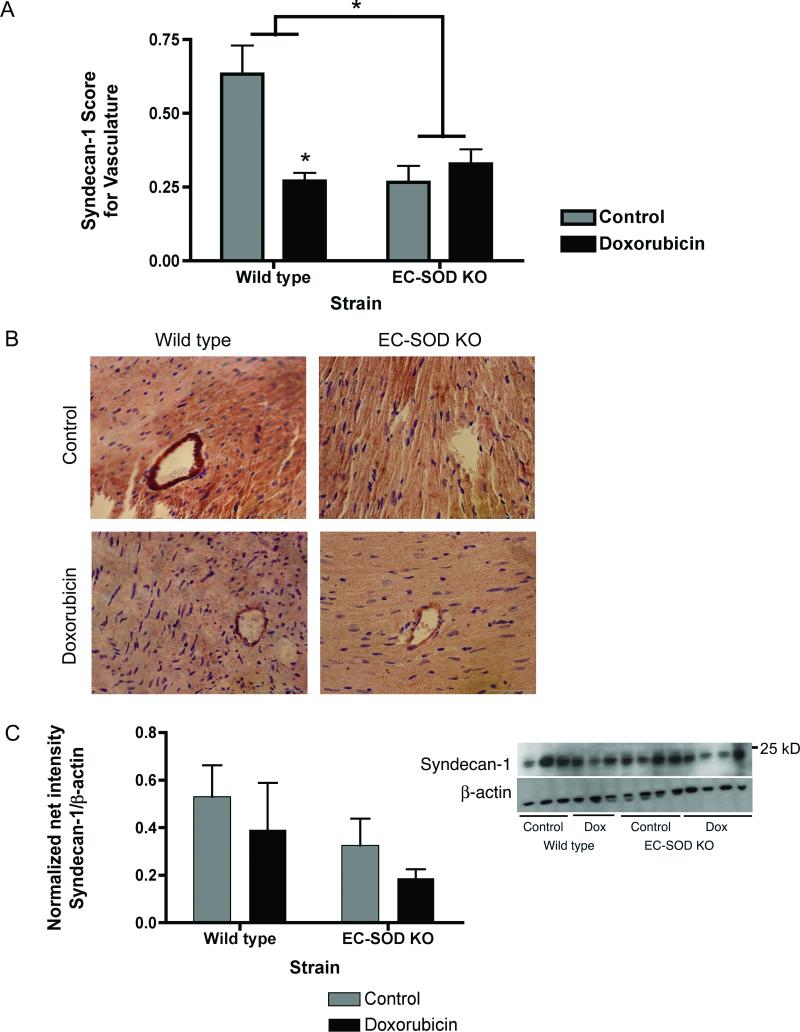

To determine the origin of the shed syndecan-1 present in the serum, syndecan-1 protein expression was evaluated in heart sections by immunohistochemical staining for syndecan-1 and in left ventricle homogenates by western blot. Syndecan-1 staining in the vasculature of the myocardium was scored on a scale of 0-no staining to 2-strong staining (see methods for details). Levels of vascular syndecan-1 staining were significantly decreased in wild type mice treated with doxorubicin (Figure 3A and B, *p<0.05). Interestingly, vascular syndecan-1 staining was significantly decreased in control-treated and doxorubicin-treated EC-SOD KO mice (Figure 3A and B, *p<0.05). After doxorubicin, syndecan-1 protein levels in left ventricle homogenates trend to decrease but is not significantly different between control and doxorubicin-treated wild type and EC-SOD KO mice. (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Syndecan-1 is shed from endothelial cells of the vasculature. Paraffin sections (4 μm) of the left ventricle were stained for syndecan-1. A) Histological scoring of syndecan-1 staining of the LV vasculature. Data are reported as mean score ± SEM, n=6. *p<0.05. Statistical analysis included non-parametric ANOVA. B) Representative images of control and doxorubicin-treated wild type and EC-SOD KO left ventricle sections stained for syndecan-1. Syndecan-1 decreases in the vasculature of doxorubicin-treated wild type mice and in both control and doxorubicin-treated EC-SOD KO mice. C) Left ventricle homogenates were evaluated for syndecan-1 by western blot. Densitometry data are normalized to ponceau red for protein loading and data are reported as mean net normalized intensity ± SEM, n=3. Doxorubicin causes a trend to decreased levels of syndecan-1, however data are not statistically significant.

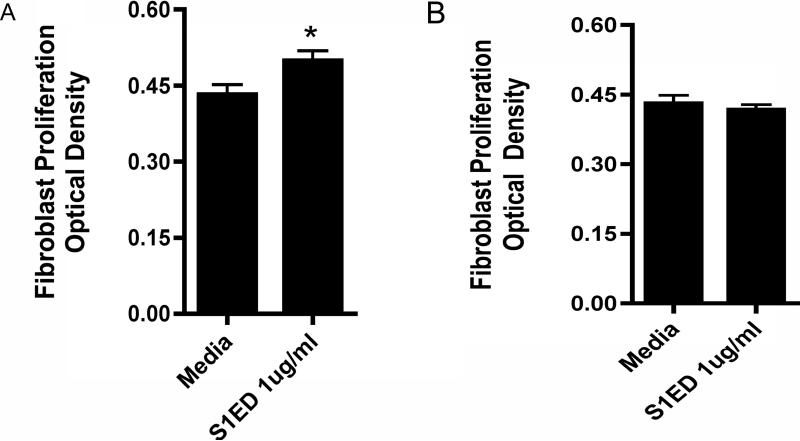

Syndecan-1 ectodomain promotes cardiac fibroblast proliferation

To determine the function of the shed syndecan-1 ectodomain in cardiac fibrogenesis, adult mouse cardiac fibroblasts were treated with 1, 2 or 3 μg/ml human syndecan-1 ectodomain core protein, in vitro, for 24 hours. The syndecan-1 ectodomain at 1μg/ml significantly increases primary mouse fibroblast proliferation after 24 hours (Figure 4A, n=12, *p<0.05). This induction of proliferation was transient, as it was no longer present after 48 hours (Figure 4B). Cell supernatants were analyzed for TGF-β1 by ELISA, however, no changes were seen in total and active protein.

Figure 4.

Shed syndecan-1 ectodomain promotes fibroblast proliferation. Primary adult mouse cardiac fibroblasts were treated with 1 μg/ml syndecan-1 ectodomain core protein for A) 24 hours or B) 48 hours. Cell proliferation was assessed. Optical density is proportional to the number of metabolically active cells. Data are reported as mean score μ SEM, n=12 *p<0.05.

Discussion

A protective role has been reported for syndecan-1 against ventricular dilation and dysfunction in ischemic cardiac injury[15]. A prior study found that EC-SOD prevents oxidative shedding of syndecan-1 from the lung epithelium and that the syndecan-1 ectodomain induces inflammation and promotes lung fibrosis[17]. Prior studies from our laboratory indicate that a loss of EC-SOD increases the severity of doxorubicin-induced cardiac fibrosis. EC-SOD KO mice treated with doxorubicin had significantly more LV fibrosis, both histologically and by hydroxyproline quantification of collagen deposition. Doxorubicin treated mice also had significant decreases in LV mass secondary to cellular apoptosis. In addition, these mice had more LV oxidative stress (shown by carbonyl formation) and LV dysfunction, shown by decreased ejection fraction and fractional shortening. Notably, administration of an exogenous SOD mimetic (AEOL 10150) was capable of protection against this loss of function and may reduce fibrosis development[9].

In this study, we show that EC-SOD KO mice treated with doxorubicin have an increase in lung:body weight ratio, providing additional evidence of cardiac dysfunction and pulmonary congestion in this model. As EC-SOD has been shown to protect against cardiac fibrosis, the current study was undertaken to test the hypothesis that EC-SOD protects against cardiac fibrosis induced by doxorubicin by preventing syndecan-1 shedding and subsequent activation of fibroblasts. Indeed, this study illustrates that oxidative stress induced by doxorubicin causes increases in shed syndecan-1 in the serum of wild type mice and that syndecan-1 ectodomain fragments induce primary cardiac fibroblast proliferation. Interestingly, control-treated EC-SOD KO mice have similar high levels of shed syndecan-1 in their serum, with a trend to increase after doxorubicin treatment. These findings suggest that EC-SOD is critical for protecting membrane-bound syndecan-1 from baseline oxidative stress and in response to doxorubicin-injury.

The serum syndecan-1 is primarily being shed from the endothelial cells of the vasculature. Syndecan-1 staining of left ventricle tissue sections shows a corresponding decrease in vascular staining of syndecan-1 within left ventricle tissue sections. Syndecan-1 levels in left ventricle homogenates do trend to decrease, however this is not significant and may reflect that myocardial syndecan-1 levels are not changing and the small decrease in the homogenates reflects the changes occurring in endothelial syndecan-1 of the myocardial vasculature. Thus, the syndecan-1 found in the serum appears to arise shedding from the vascular endothelium and this shedding is inhibited by EC-SOD. Syndecan-1 that is shed from the endothelium can then gain access to a wide variety of cell types, including fibroblasts.

In addition, EC-SOD KO mice have significantly lower syndecan-1 mRNA expression at day 15 compared to wild type mice after doxorubicin treatment. These findings suggest that the loss of EC-SOD increases syndecan-1 shedding from the vasculature and decreases syndecan-1 expression in cardiac tissue. The changes in expression may be due to the increased levels of reactive oxygen species that are believed to also have roles as signaling molecules[2, 25]. Vanhoutte et al. found that expression of syndecan-1 provided protection against dilation and contractile dysfunction in a model of myocardial infarction and that syndecan-1 mRNA expression increased after infarction, reached a maximum at 7 days then began to decline[15]. It has also been found that lack of syndecan-1 expression results in less cardiac fibrosis and collagen deposition in a model of angiotensin-II induced pressure overload [26]. In the current study, the increased shedding of syndecan-1 may promote myocardial dilation and loss of function in the ventricle by modulating matrix remodeling of the heart, while the loss of syndecan-1 expression may be a protective response by the myocardium.

Syndecan-1 has various known functions as a membrane-bound proteoglycan, however, the functions of the shed, soluble ectodomain remain unclear. A previous study found that two functions of the syndecan-1 ectodomain during pulmonary fibrosis include promoting lung fibroblast proliferation and increasing TGF-β1 bioavailability[17]. Previous studies have investigated the role of syndecan-1 in tissue remodeling and fibroblast biology. In a model of angiotensin II pressure-induced cardiac fibrosis, syndecan-1 null mice had less fibrosis and cardiac dysfunction than wild-type mice and in vitro knock-down of syndecan-1 resulted in a decrease in collagen-I expression [26]. These data suggest that syndecan-1 is important for fibrogenesis. In Syndecan 1-null keratinocytes TGF-beta signaling was elevated, however, downstream signaling via Smad2 phosphorylation was impaired and collagen production was decreased [27]. Kato et al. show that fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2), a potent mitogenic factor for mesenchymal cells, is activated by the shed ectodomain of syndecan-1 in injured tissue[28]. To elucidate the mechanisms through which the lack of EC-SOD and increased serum syndecan-1 may promote fibrosis in the heart, the role of shed syndecan-1 in primary mouse cardiac fibroblasts was investigated. The syndecan-1 ectodomain core protein significantly increases the proliferation of primary cardiac fibroblasts, however, does not alter TGF-beta expression after 24 hours. This suggests a unique mechanism and role for the syndecan-1 ectodomain in the pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis.

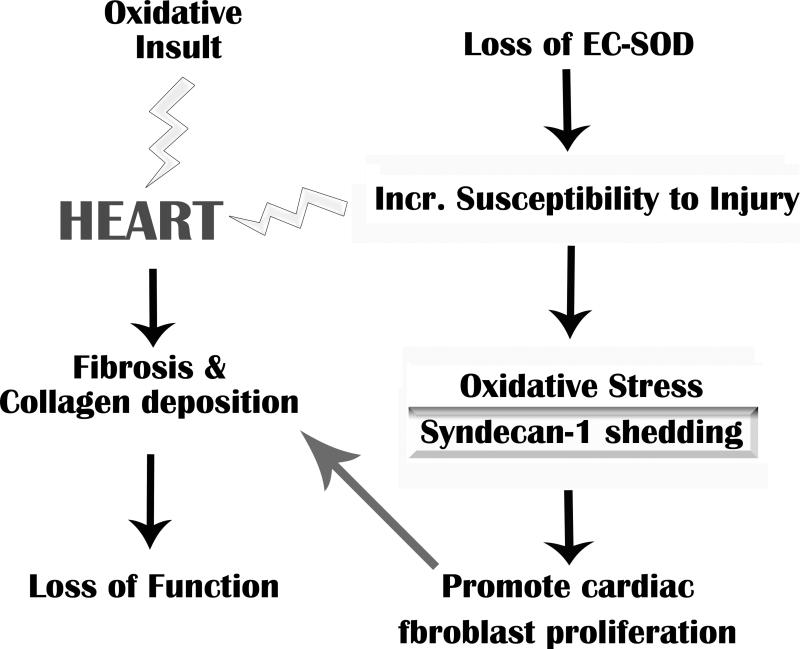

In summary, this study shows that EC-SOD protects vascular syndecan-1 from oxidative shedding, thus regulating oxidant-induced fibrosis. Oxidative injury to the heart can result in matrix remodeling, fibrosis and loss of function (Figure 5 Schematic). The loss of EC-SOD in the cardiovascular system increases the susceptibility of the tissue to oxidative injury and subsequent oxidative shedding of syndecan-1. Matrix remodeling is promoted by the profibrotic function gained by the syndecan-1 ectodomain protein when it is shed, as well as, a loss of the potential protective effects of intact membrane-associated syndecan-1. This data provides novel targets for potential therapeutic avenues to control cardiac fibrosis and tissue remodeling.

Figure 5.

Summary schematic of the role of oxidative stress and syndecan-1 in cardiac fibrosis. Oxidative injury to the heart, which is regulated by EC-SOD, can result in matrix remodeling, fibrosis and loss of function. An increase in oxidative injury and subsequent shedding of syndecan-1 ectodomains may further promote fibrosis in the myocardium.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Alan Rapraeger, University of Wisconsin, for providing the syndecan-1 ectodomain. Many thanks to Beth Ganis, Lauren Tomai and the Cardiovascular Institute for their technical assistance. This work was supported by the following NIH grants: F30ES016483 to CRK and a research project grant RO1HL063700 to TDO.

Abbreviations

- ECM

Extracellular Matrix

- EC-SOD

Extracellular superoxide Dismutase

- KO

Knock out

- TGF-β1

Tumor Growth Factor β1

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Chen EP, et al. Extracellular superoxide dismutase transgene overexpression preserves postischemic myocardial function in isolated murine hearts. Circulation. 1996;94(9 Suppl):II412–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fattman CL, Schaefer LM, Oury TD. Extracellular superoxide dismutase in biology and medicine. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35(3):236–56. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00275-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Juul K, et al. Genetically reduced antioxidative protection and increased ischemic heart disease risk: The Copenhagen City Heart Study. Circulation. 2004;109(1):59–65. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000105720.28086.6C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Deel ED, et al. Extracellular superoxide dismutase protects the heart against oxidative stress and hypertrophy after myocardial infarction. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44(7):1305–13. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petersen SV, et al. Extracellular superoxide dismutase (EC-SOD) binds to type i collagen and protects against oxidative fragmentation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(14):13705–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310217200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandstrom J, et al. Heparin-affinity patterns and composition of extracellular superoxide dismutase in human plasma and tissues. Biochem J. 1993;294(Pt 3):853–7. doi: 10.1042/bj2940853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oury TD, Day BJ, Crapo JD. Extracellular superoxide dismutase in vessels and airways of humans and baboons. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;20(7):957–65. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)02222-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Folz RJ, Crapo JD. Extracellular superoxide dismutase (SOD3): tissue-specific expression, genomic characterization, and computer-assisted sequence analysis of the human EC SOD gene. Genomics. 1994;22(1):162–71. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kliment CR, et al. Extracellular superoxide dismutase regulates cardiac function and fibrosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47(5):730–42. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu Z, et al. Extracellular superoxide dismutase deficiency exacerbates pressure overload-induced left ventricular hypertrophy and dysfunction. Hypertension. 2008;51(1):19–25. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.098186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu Y, et al. Vascular effects of the human extracellular superoxide dismutase R213G variant. Circulation. 2005;112(7):1047–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.531251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petersen SV, et al. The high concentration of Arg213-->Gly extracellular superoxide dismutase (EC-SOD) in plasma is caused by a reduction of both heparin and collagen affinities. Biochem J. 2005;385(Pt 2):427–32. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartlett AH, Hayashida K, Park PW. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of syndecans in tissue injury and inflammation. Mol Cells. 2007;24(2):153–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernfield M, et al. Functions of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:729–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vanhoutte D, et al. Increased expression of syndecan-1 protects against cardiac dilatation and dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;115(4):475–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.644609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Q, et al. Matrilysin shedding of syndecan-1 regulates chemokine mobilization and transepithelial efflux of neutrophils in acute lung injury. Cell. 2002;111(5):635–46. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kliment CR, et al. Oxidative stress alters syndecan-1 distribution in lungs with pulmonary fibrosis. J Biol Chem. 2008 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807001200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kliment CR, et al. Extracellular superoxide dismutase protects against matrix degradation of heparan sulfate in the lung. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10(2):261–8. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalyanaraman B, Perez-Reyes E, Mason RP. Spin-trapping and direct electron spin resonance investigations of the redox metabolism of quinone anticancer drugs. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980;630(1):119–30. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(80)90142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singal PK, Iliskovic N. Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(13):900–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809243391307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlsson LM, et al. Mice lacking extracellular superoxide dismutase are more sensitive to hyperoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(14):6264–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Englert JM, et al. A role for the receptor for advanced glycation end products in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2008;172(3):583–91. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burger A, et al. Catecholamines stimulate interleukin-6 synthesis in rat cardiac fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281(1):H14–21. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.1.H14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaffre F, et al. Involvement of the serotonin 5-HT2B receptor in cardiac hypertrophy linked to sympathetic stimulation: control of interleukin-6, interleukin-1beta, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha cytokine production by ventricular fibroblasts. Circulation. 2004;110(8):969–74. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000139856.20505.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma S, et al. Induction of antioxidant gene expression in a mouse model of ischemic cardiomyopathy is dependent on reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40(12):2223–31. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schellings MW, et al. Syndecan-1 amplifies angiotensin II-induced cardiac fibrosis. Hypertension. 55(2):249–56. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.137885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stepp MA, et al. Reduced migration, altered matrix and enhanced TGFbeta1 signaling are signatures of mouse keratinocytes lacking Sdc1. J Cell Sci. 2007;120(Pt 16):2851–63. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kato M, et al. Physiological degradation converts the soluble syndecan-1 ectodomain from an inhibitor to a potent activator of FGF-2. Nat Med. 1998;4(6):691–7. doi: 10.1038/nm0698-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]