Abstract

Background

Risk factors for severe human rhinovirus (HRV)–associated infant illness are unknown.

Objectives

We sought to examine the role of HRV infection in infant respiratory tract illness and assess viral and host risk factors for HRV-associated disease severity.

Methods

We used a prospective cohort of term, previously healthy infants enrolled during an inpatient or outpatient visit for acute upper or lower respiratory tract illness during the fall-spring months of 2004-2008. Illness severity was determined by using an ordinal bronchiolitis severity score, with higher scores indicating more severe disease. HRV was identified by means of real-time RT-PCR. The VP4/VP2 region from HRV-positive specimens was sequenced to determine species.

Results

Of 630 infants with bronchiolitis or upper respiratory tract illnesses (URIs), 162 (26%) had HRV infection; HRV infection was associated with 18% of cases of bronchiolitis and 47% of cases of URI. Among infants with HRV infection, 104 (64%) had HRV infection alone. Host factors associated with more severe HRV-associated illness included a maternal and family history of atopy (median score of 3.5 [interquartile range [IQR], 1.0-7.8] vs 2.0 [IQR, 1.0-5.2] and 3.5 [IQR, 1.0-7.5] vs 2.0 [IQR, 0-4.0]). In adjusted analyses maternal history of atopy conferred an increase in the risk for more severe HRV-associated bronchiolitis (odds ratio, 2.39; 95% CI, 1.14-4.99; P = .02). In a similar model maternal asthma was also associated with greater HRV-associated bronchiolitis severity (odds ratio, 2.49, 95% CI, 1.10-5.67; P = .03). Among patients with HRV infection, 35% had HRVA, 6% had HRVB, and 30% had HRVC.

Conclusion

HRV infection was a frequent cause of bronchiolitis and URIs among previously healthy term infants requiring hospitalization or unscheduled outpatient visits. Substantial viral genetic diversity was seen among the patients with HRV infection, and predominant groups varied by season and year. Host factors, including maternal atopy, were associated with more severe infant HRV-associated illness.

Key words: Rhinovirus, HRVC, infants, atopy, asthma, bronchiolitis, maternal

Abbreviations used: HRV, Human rhinovirus; IQR, Interquartile range; ISAAC, International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood; OR, Odds ratio; RSV, Respiratory syncytial virus; URI, Upper respiratory tract illness

Discuss this article on the JACI Journal Club blog: www.jaci-online.blogspot.com.

Human rhinoviruses (HRVs) are the most common viral cause of asthma exacerbations in adults and children,1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and wheezing with HRV infection during infancy has been linked to the onset of asthma.10, 11, 12 Although it is well recognized that the majority of upper respiratory tract illness (URI) episodes in adults and children are associated with HRV infection, HRV historically have not been thought to play a significant role in infant respiratory tract illness or morbidity. During recent years, in studies with sensitive RT-PCR, HRVs have been associated with a significant burden of disease in infants and young children.13, 14, 15 Bronchiolitis, a lower respiratory tract infection in infants presenting with wheezing, rales, and respiratory distress, has typically been associated with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection,14, 16 but a number of studies suggest that HRVs are another important cause of bronchiolitis.13, 15, 17, 18, 19

Host factors for HRV-associated illness are poorly defined compared with those for RSV-induced illness. Copenhaver et al20 found that among high-risk infants of atopic parents, day care attendance and siblings were risk factors for HRV-associated wheezing. However, the spectrum of HRV-associated illness among infants who are not at high risk for atopy and host and viral risk factors for HRV-associated infant bronchiolitis are not well defined. Some viral factors important in childhood respiratory morbidity have recently been elucidated in relation to wheezing illnesses in older children. These recent studies have found that a novel group of HRVs, called HRVC, is associated with a substantial burden of respiratory tract illness in sick children.1, 13, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31

We sought to assess the importance of HRVs, including HRVC, as a cause of URI or bronchiolitis among term, non–low birth weight, previously healthy infants without known risk factors for bronchiolitis and to examine host and viral factors that might contribute to HRV pathogenesis. A better understanding of host and viral risk factors for HRV-associated infant morbidity will have implications not only for understanding HRV pathogenesis but for treatment and disease prevention strategies.

Methods

Clinical biospecimens and clinical data available from the Tennessee Children’s Respiratory Initiative were used for this investigation, the methods for which have been previously described.32 The Tennessee Children’s Respiratory Initiative is a longitudinal prospective investigation of term, non–low birth weight, otherwise healthy infants and their biological mothers. The primary goals of the cohort are to investigate the acute and long-term health consequences of varying severity and cause of viral respiratory tract infections and other environmental exposures on the outcomes of allergic rhinitis and early childhood asthma and to identify the profile of children at greatest risk of asthma after infant respiratory tract viral infection.32 Infants aged less than 12 months were enrolled at the time of a clinical visit (hospitalization, emergency department visit, or outpatient visit) for bronchiolitis or URI from Fall through Spring, 2004-2008. Repeat infections were not included. Demographic and clinical data were collected, and nasopharyngeal swabs were obtained by trained nurses for viral testing, as described below. The children underwent an outpatient follow-up visit between the ages of 12 and 24 months in the Vanderbilt General Clinical Research Center, where infant and maternal blood was obtained and an additional parental questionnaire was completed.

Atopy risk

Clinical evidence of maternal atopy was determined based on clinical symptoms of an atopic disease as assessed by the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) questionnaire (allergic rhinitis, asthma, and/or atopic dermatitis).32 Laboratory evidence of maternal atopy was ascertained by means of skin testing or specific IgE measurement.32 Maternal asthma was ascertained by using the ISAAC questionnaire.32 Family history of atopy was determined based on reports of first-degree relatives with an atopic disease.

Infant acute respiratory tract illness severity

Acute respiratory tract illness severity was determined by using an ordinal bronchiolitis score that incorporates admission information on respiratory rate, flaring or retractions, room air oxygen saturation, and wheezing into a score ranging from 0 to 12, with 12 being the most severe.33, 34

Molecular testing

Nasal and throat swabs were obtained from ill infants by trained nurses and placed together into both lysis buffer and viral transport medium. Specimens were taken immediately to the laboratory on ice, divided into aliquots, and stored at −80°C until processed. RNA was extracted from 200 μL of pooled nasal/throat swab media on a Roche MagNApure LC automated nucleic acid extraction instrument (Roche, Mannehim, Germany), and real-time RT-PCR for the detection of HRV was performed as previously described.35, 36, 37, 38 Specimens were also tested for RSV, influenza viruses A and B, parainfluenza virus types 1 to 3, human metapneumovirus, and coronaviruses (including OC43, 229E, and NL63).35, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45 Conventional RT-PCR was performed on HRV-positive samples by using primers that amplify a fragment of approximately 548 nt encompassing the VP4/VP2 region.46 Amplified fragments were sequenced in the Vanderbilt DNA Sequencing Core, edited, and aligned with MacVector version 11.1 (MacVector, Cary, NC). Phylogenetic analysis was performed with Mega version 4 by using 500 bootstrapped replicates and the neighbor-joining algorithm with HRV87 as the outgroup.47 Nucleotide identity between strains within each HRV species (A, B, or C) was calculated, and the mean diversity between HRV species was compared with a 2-tailed t test assuming unequal variance.

Statistical methods

Host factors were presented with medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) or frequencies and proportions as appropriate and were compared between HRV-positive and HRV-negative (other or no study virus) subjects by using the χ2 test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables. To assess for adjusted effects of host factors on the bronchiolitis severity score, we used multivariable ordinal logistic regression (proportional odds model). Factors included were the infant’s illness age, sex, gestational age, race, smoking, and coinfection status and maternal history of atopy. Separate adjusted models were used to assess the role of maternal asthma, family history of atopy, and laboratory and clinically assessed maternal atopy. The main findings are presented based on the 162 infants with HRV infection to assess broadly the scope of HRV-associated illness. Because coinfections with other viruses can affect clinical presentation, a sensitivity analysis restricted to the HRV group without coinfection for other tested viruses was performed to assess for host factors mentioned above and the severity of bronchiolitis.

We examined the variation of HRV species by year graphically. Multinomial logistic regression was used to assess independent associations between host factors and HRV species (A, B, or C). The proportional odds model was used to examine whether HRV species were associated with outcomes of respiratory tract illness severity independent of the infant’s age, race, and sex. The independent association of HRV species with the length of stay outcome was assessed by using the same covariates and the proportional odds model. R (version 2.10.1, www.r-project.org) was used for all statistical analyses. A P value of less than .05 was considered significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Six hundred thirty infants with either a URI or bronchiolitis were enrolled over 4 respiratory viral seasons from 2004-2008. One hundred sixty-two (26%) of these had positive test results by means of real-time RT-PCR for HRV infection and are the focus of this investigation. Of all enrolled infants with bronchiolitis, 18% had HRV infection; of all infants with URIs, 47% had HRV infection. Among the 162 infants studied with HRV infections, 81 (50%) had bronchiolitis, and 81 (50%) had URIs. One hundred four subjects had HRV infection only with no other virus detected, 44 (42%) of whom were hospitalized. Of the children infected with HRV alone, 37 (36%) were female, 32 (31%) were black, 18 (17%) were Hispanic, 38 (37%) were white, and 16 (15%) were of “other” race. Median infant age at enrollment for patients with HRV infection only was 20 weeks (IQR, 8-39), and maternal age was 24 years (IQR, 21.0-30.0 years). Eighty-one (78%) infants with HRV infection only had public insurance, 15 (14%) had private insurance, 1 (1%) had other insurance, and 7 (7%) were uninsured.

Risk factors for HRV-associated disease severity

Table I depicts demographic and clinical differences in infants who had HRV-associated bronchiolitis versus those with HRV-associated URIs. Infants with HRV-associated bronchiolitis versus infants with HRV-associated URIs were more likely to be white (57% vs 30%, P overall for race distributions = .003) and less likely to be on Medicaid (59% vs 84%, P = .005), more likely to have a family history of atopy (77% vs 59%, P = .018), and more likely to have coinfection with another virus (42% vs 11%, P < .001). Fifty-four percent of infants with HRV-associated bronchiolitis had atopic mothers versus 40% of infants with HRV-associated URIs (P = .059).

Table I.

Demographic and clinical characteristics by HRV-associated bronchiolitis and HRV-associated URIs (coinfections included)

| HRV + bronchiolitis (n = 81), % (no.) | HRV + URI (n = 81), % (no.) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (wk)∗ | 8.0 (13.0-26.0) | 7.0 (20.0-42.0) | .75 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Black | 19 (15) | 35 (28) | .003 |

| Hispanic | 17 (14) | 19 (15) | |

| White | 57 (46) | 30 (24) | |

| Other/unknown | 7 (6) | 17 (14) | |

| Medicaid | 59 (48) | 84 (68) | .005 |

| Study site | <.001 | ||

| Inpatient | 83 (67) | 16 (13) | |

| Outpatient | 17 (14) | 84 (68) | |

| Day care | 36 (29) | 29 (23) | .37 |

| Smoking in home | 59 (47) | 49 (38) | .21 |

| Breast-fed | 58 (47) | 61 (48) | .72 |

| Bronchiolitis severity score∗ | 4.0 (6.5-8.5) | 0.0 (1.0-2.0) | <.001 |

| Family history of atopy | 77 (62) | 59 (48) | .018 |

| Maternal atopy | 54 (44) | 40 (32) | .059 |

| Coinfection | 42 (34) | 11 (9) | <.001 |

Values are medians (IQRs).

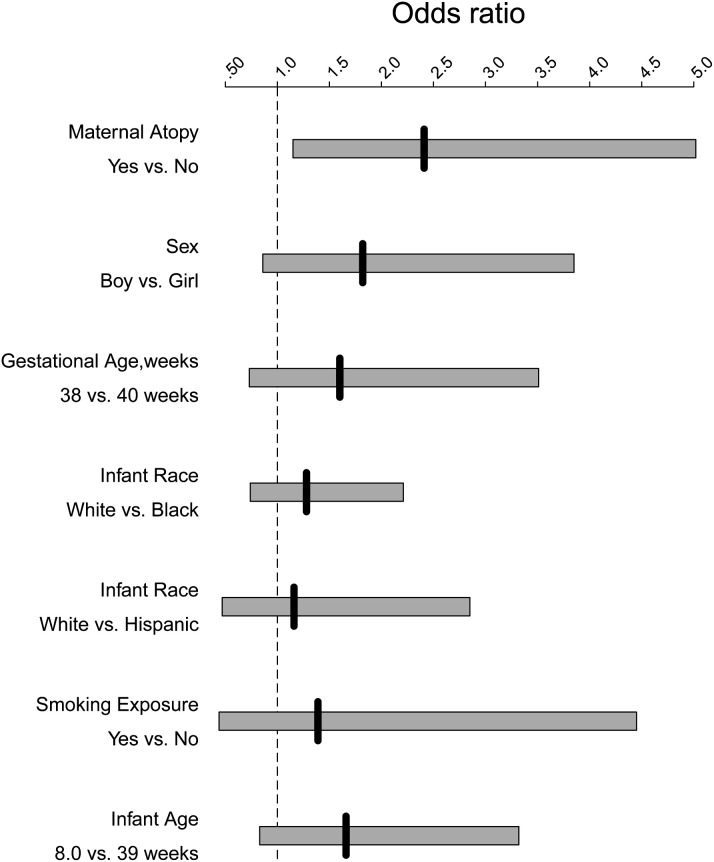

Controlling for age, race, smoking, and sex, maternal history of atopy conferred an increase in risk for more severe HRV-associated bronchiolitis (odds ratio [OR], 2.39; 95% CI, 1.14-4.99; P = .02). In a similar model maternal asthma was also associated with HRV-associated bronchiolitis severity (OR, 2.49; 95% CI, 1.10-5.67; P = .03). Fig 1 depicts the ORs of risk factors for HRV-associated disease severity.

Fig 1.

Risk factors for HRV-associated infant respiratory tract disease severity. Solid vertical lines represent ORs, and bars represent 95% CIs.

Infants with HRV infection alone differ from infants with no HRV infection

Of 455 infants enrolled with bronchiolitis, 18% had HRV infection (9% had HRV infection only without coinfections). Of 175 infants enrolled with URIs, 47% had HRV infection (36% with HRV infection only). Of 104 infants studied with HRV infection only (no coinfections), 39% (n = 41) had bronchiolitis and 61% (n = 63) had URIs. Clinical features of infants with HRV and RSV coinfection were similar to those of infants with RSV alone, and thus coinfections were excluded from HRV analysis (data not shown). Demographic and clinical differences between infants with HRV infection alone versus infants who did not have HRV infection (other or no study virus detected) are compared in Table II . Infants with HRV infection alone were more likely to be older (20 weeks [IQR, 8-39 weeks] vs 11 weeks [IQR, 6-25 weeks], P < .001). There were racial distribution differences (P = .005); a higher proportion of infants with HRV infection were black (31% vs 21% white). Infants with HRV infection alone were also more likely to be outpatients (58% vs 27%, P < .001) and attend day care (33% vs 21%, P = .012) compared with infants with respiratory tract illnesses associated with other or no study virus. Infants with HRV infection alone were more likely to have had a lower median bronchiolitis severity score (2.0, [IQR, 1.0-5.5] vs 5.0 [IQR, 2.0-8.0], P < .001), require less supplemental oxygen (18% vs 51%, P < .001), and be given a diagnosis of a URI (61% vs 20%, P < .001). Duration of hospitalization for infants with HRV infection alone was 2.0 days (IQR, 2.0-3.0 days) compared with that of infants with other or no viral causes of respiratory tract illness, whose duration of hospitalization was 3.0 days (IQR, 2.0-4.0 days; P = .13). Infants with HRV infection alone were more likely to have a maternal history of asthma (29% vs 18%, P = .009) compared with infants with respiratory tract illnesses associated with other or no study virus.

Table II.

Demographic and clinical associations in infants with HRV-associated respiratory tract illness only (no coinfections) and non–HRV-associated infant respiratory tract illness (other or no study virus detected)

| HRV+ only (n = 104), % (no.) | HRV− (n = 465), % (no.) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (wk)∗ | 8 (20-39) | 6 (11-25) | <.001 |

| Female sex | 36 (37) | 45 (207) | .096 |

| Race/ethnicity | .005† | ||

| Black | 31 (32) | 21 (97) | |

| Hispanic | 17 (18) | 12 (54) | |

| White | 37 (38) | 56 (259) | |

| Other/unknown | 15 (16) | 12 (55) | |

| Medicaid | 78 (81) | 66 (308) | .071 |

| Study year | .67† | ||

| Nov 2004–May 2005 | 24 (25) | 28 (130) | |

| Sept 2005–May 2006 | 38 (39) | 32 (149) | |

| Sept 2006–May 2007 | 25 (26) | 24 (113) | |

| Sept 2007–May 2008 | 13 (14) | 16 (73) | |

| Study site | <.001 | ||

| Inpatient | 42 (44) | 73 (339) | |

| Outpatient | 58 (60) | 27 (126) | |

| Day care | 33 (34) | 21 (98) | .012 |

| Breast-fed | 62 (64) | 56 (259) | .30 |

| Smokers in home | 51 (52) | 55 (252) | .46 |

| Bronchiolitis severity score∗‡ | 1.0 (2.0-5.5) | 2.0 (5.0-8.0) | <.001 |

| Supplemental oxygen | 18 (19) | 51 (236) | <.001 |

| Hospital days among hospitalized∗ | 1.0 (2.0-3.0) | 2.0 (3.0-4.0) | .037 |

| Discharge diagnosis | |||

| Bronchiolitis | 39 (41) | 80 (372) | <.001 |

| URI | 61 (63) | 20 (93) | |

| Maternal asthma | 29 (30) | 18 (82) | .009 |

Values are medians (IQRs).

P value reflects comparison of all groups.

HRV species differences

Of the HRV-positive specimens, 57 (35%) were species HRVA, 9 (6%) were HRVB, 49 (30%) HRVC, and 47 (29%) could not be sequenced. Although the number of infants hospitalized with HRVB was small (n = 7), 56% required supplemental oxygen (vs 25% with HRVA and 18% with HRVC, P = .059). Infants with HRVB had a longer duration of stay (median of 4 days [IQR, 3-5.5 days] for HRVB vs 2 days [IQR, 2-4 days] for HRVA and 2 days [IQR, 1.25-3 days] for HRVC, P = .038). Among patients with HRVC infection, there were racial distribution differences, with a higher proportion of infants who had HRVC infection being black (41% with HRVC vs 0% with HRVB and 26% with HRVA, P = .019). Maternal atopy was identified in 67% of infants with HRVB infection compared with 46% with HRVA and 45% with HRVC infection (P = .47). When comparing HRVA and HRVC, infants with HRVC infection were less likely to attend day care than those with HRVA infection (20% with HRVC vs 38% with HRVA infection, P = .048).

In our multinomial logistic regression analysis there was no difference in infant age at illness or sex between HRV species. In this adjusted analysis the OR for the association of race with HRV species was 0.39 (95% CI, 0.15-1.00; P = .049) for white versus black for HRVC versus HRVA. In an ordinal logistic regression model adjusting for age, sex, and race, HRV species factors were not associated with increased bronchiolitis severity (P = .078). In a similar adjusted regression model species was significantly associated with length of stay (P = .024). HRVB infection was associated with increased length of stay compared with HRVA infection (OR, 6.26; 95% CI, 1.11-35.48). Our results are limited by sample size, particularly for our multinomial logistic regression analyses that use multiple equations with only 9 patients in the HRVB species group.

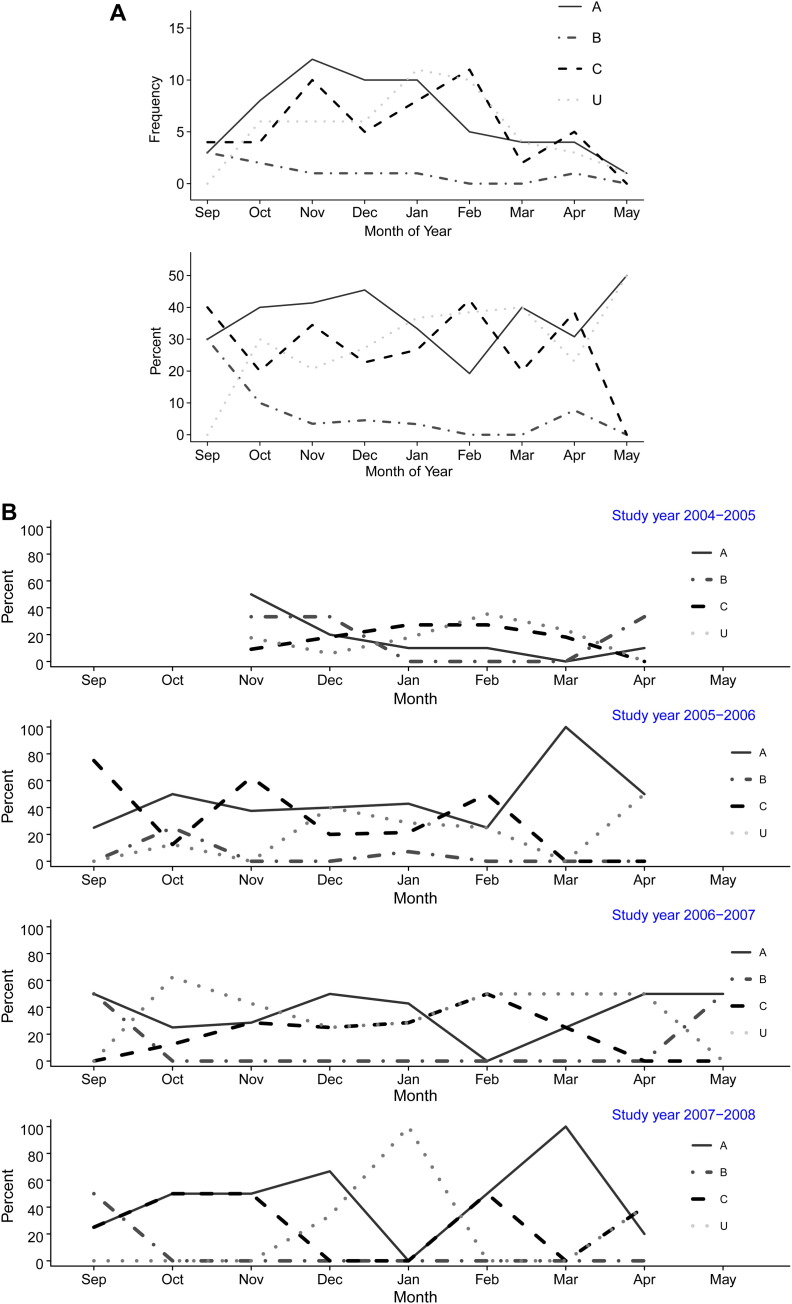

HRV seasonal variation

There was marked variability between HRV species by season and by year, as shown in Fig 2 . In addition to peaks of HRVA or HRVC during certain seasons and years, there was also a peak in untyped HRVs seen in January 2008.

Fig 2.

A, Seasonality of HRV-associated respiratory tract illness in infants by HRV species over a 4-year period. Frequency is defined as the number of infections with HRV species. Percent is defined as the proportion of each HRV species over the total of HRV-positive specimens. B, Seasonality of HRV-associated respiratory tract illness in infants by HRV species by year. Frequency is defined as the number of infections with HRV species. Percent is defined as the proportion of each HRV species over the total of HRV-positive specimens. U, Untyped.

HRV diversity

The genetic variance of HRV strains in this cohort is shown in Fig 3 . Although some clinical differences were seen between patients infected with different HRV groups, there were also broad genetic differences among viruses. The VP4/VP2 sequence regions correlate with the serotype classification of HRV.46, 48, 49 HRVC strains were defined by using a nucleotide identity of less than 90% based on the calculated genetic relatedness of established serotypes, as previously described.1 The HRVC genotypes had a mean nucleotide identity of 66.2% (minimum of 23.3% and maximum of 99.6%) compared with HRVA (mean of 72.0%, minimum of 31.0%, and maximum of 99.8%) and HRVB (mean of 73.5%, minimum of 54.7%, and maximum of 99.8%). Thus HRVC viruses exhibited a substantial amount of diversity among themselves that was significantly greater than that observed for HRVA (mean diversity for HRVA vs HRVC, P < .001) or HRVB (mean diversity for HRVB vs HRVC, P < .001).

Fig 3.

Phylogenetic tree depicting relationships between known HRV serotypes and novel HRVC species. The bar indicates the mean distance of 0.05 nucleotide substitutions per site. Published HRV strains are designated by HRV and a black circle. Sequences identified in this study are designated by number. The numbers in parentheses after the label of these sequences indicates how many additional specimens contained each virus.

Discussion

HRV is recognized as a virus of older children associated primarily with URIs,6, 9, 50 but the role of HRV in term, non–low birth weight, previously healthy infants who are not selected to be at high risk for atopy has not been as well studied. We detected HRV in 18% of bronchiolitis cases and 47% of cases of URI among infants enrolled over 4 respiratory viral seasons. Thus HRV infection appears to be an important cause of infant bronchiolitis. Kusel et al51 reported that among 263 infants with acute respiratory tract illness during the first year of life, half were associated with HRV, with HRV being the most common virus detected in children with upper and lower respiratory tract illnesses. However, this finding has not been consistent. Another group identified HRV in only 9% of infants with bronchiolitis,14 and others have detected HRV in 7% to 17% of cases of bronchiolitis in children less than 2 years of age.52, 53 This variability in apparent HRV burden might depend on both the study population and the years of study, as suggested by the differential circulation of HRV in each of the seasons studied in this investigation.

Infants with HRV infection alone were more likely to be older, be black, attend day care, and have a maternal asthma history compared with infants with respiratory tract illnesses associated with other viruses or with no virus detected. Maternal atopy conferred more than twice the risk of more severe HRV-associated respiratory tract illness, as determined by the bronchiolitis severity score, independent of age, race, smoking, and sex. Korppi et al54 compared infants less than 24 months of age with HRV infection versus RSV-associated wheezing and reported that infants with HRV infection were older and more often had atopic dermatitis and eosinophilia. These data are consistent with our findings that infants with HRV-associated respiratory illnesses are older and that an atopic profile in the mother might be an important risk factor for more severe HRV-associated infant disease. Other cohort studies, such as the Childhood Origins of Asthma study, have elegantly described risk factors for infant virus-associated wheezing and subsequent early childhood wheezing/asthma; however, all infants in those cohorts had 1 or both parents with atopy or asthma and thus constituted a high-risk population.10, 11, 20 In contrast, our study included infants with no history of maternal atopy as defined by the ISAAC questionnaire; 56% (354/630) of the infants enrolled did not have a history of maternal atopy. Although there are not immediate clinical implications from our study for asthma development, children in this cohort are being followed until the sixth year of life for the outcomes of asthma and allergic rhinitis. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to find that maternal atopy is an independent risk factor for HRV disease severity among term, non–low birth weight infants who are not selected to be at high risk for atopy, suggesting that there is a genetic predisposition to HRV severity and that risk factors for atopy might be linked with risk factors for innate immunity to HRV. Airway epithelial cells from asthmatic subjects have been shown to exhibit aberrant responses to HRV infection in vitro 55, 56; our findings suggest that these mechanisms can affect clinical disease.

We found a large proportion of HRV species to be the newly described group HRVC. The diversity seen among HRVC strains was greater than that seen among HRVA strains, which is consistent with other studies.1, 13 All of the recently described HRVs for which the VP4/VP2 sequences are available fell into the same group, including the QPM strains from Queensland that were originally classified as a subgroup of HRVA.1, 21, 23, 31, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62 Infants with HRVB infection were more likely to require supplemental oxygen and have a longer duration of hospitalization compared with infants with HRVA or HRVC infection. Consistent with these findings, infants with HRVB infection tended to have higher bronchiolitis severity scores, although the number of HRVB strains was small, as in other studies.1, 13, 63 HRVC was more commonly seen in black infants compared with HRVA or HRVB. Our prior study also found HRVC infection to be significantly more common in black children less than 5 years of age who were hospitalized with acute respiratory tract illnesses or fever during 1 year and in 1 study site, but this effect was not significant during both study years and in both sites in that investigation.1 One cannot assume ethnic differences in predisposition to HRVC infection based on these limited data because the effects could have merely been seen based on viral circulation patterns among different geographic or socioeconomic regions, but these findings suggest that both host and viral genetic factors might be important in disease pathogenesis.

A recent multiyear population-based study of HRVC infection in 2 US locations found that HRVC was associated with medically diagnosed wheezing and asthma more frequently than other HRV species.1 Other reports also suggest that viruses in the HRVC group are more likely to be associated with wheezing.21, 23, 31, 57, 60, 61 However, we did not find a significant association between HRVC infection and bronchiolitis severity in the current study. It is possible that clinical features among children who are ill with certain strains or species of HRV differ based on age or other demographic or epidemiologic factors, and we only enrolled children less than 12 months of age. In addition, specific genotypes within species A, B, or C might be more likely to be associated with increased disease severity. Further studies are required to address these possibilities.

When examining the frequency and proportions of HRV species by year in our study, there are clearly annual variations and alternation of the 2 major species during a single year and sometimes recurrence at certain times of the year. Of the studies that have tested for HRVC infection to date, data on the seasonality of HRVC species are not conclusive. Although many studies have detected HRVC as the predominant HRV species in the fall, suggesting it might play a role in the so-called September asthma epidemic,21, 22, 23 other studies in different regions and years have found otherwise. Han et al28 reported HRVC to be more common in the spring and HRVA in the fall in South Korea in 2006, but cocirculation occurred during both seasons. Consistent with our studies, Lau et al64 found HRVA and HRVC to alternate as the most common HRV species at different times during the peak seasons. Alternate disease activity by species and seasons suggests possible viral interference or serological cross-protection between HRVA and HRVC.64 Although one study reported HRVC year round without peaks in the spring and fall,25 most studies do suggest that HRV species vary by season, year, and geographic location. This variation underscores the importance of studies over multiple years and seasons to understand fully the geographic and seasonal HRV epidemiology.

Study limitations

Despite the strengths of our prospective cohort study, there are limitations that should be noted. First, we did not test concurrent healthy control subjects to determine the prevalence of asymptomatic HRV infection, which is well described.24, 51, 52 Because HRV can cause asymptomatic infection, our data suggest but do not prove that HRV infection was the causative agent for the respiratory tract illnesses, bronchiolitis, and URIs. However, we performed highly sensitive molecular testing for the spectrum of viruses known to cause infant respiratory tract viral illnesses, including influenza, RSV, human metapneumovirus, parainfluenza virus types 1 to 3, and human coronaviruses, including OC43, 229E, and NL63 (data not shown), with no other virus detected in 73.5% of the HRV-positive children, strongly suggesting that HRV was the causative pathogen. Other studies support these findings.53, 54 In addition, this study cannot delineate population-based rates of HRV-associated lower respiratory tract illnesses and URIs because the cohort did not equally enroll hospitalized and nonhospitalized infants, with nearly two thirds of the cohort being hospitalized infants, thus overrepresenting infants with bronchiolitis. A final limitation was that we evaluated only 1 geographic site. However, we report a comprehensive study over 4 years in a site that captures more than 90% of Nashville-Davidson county infant hospitalizations.

Conclusion

In this study HRV infections were frequently associated with bronchiolitis and clinically significant URIs in previously healthy term infants. Predominant HRV groups varied by season and year, with substantial genetic diversity. HRVB infection was associated with more severe disease in univariate analyses. Maternal atopy and asthma were associated with more severe infant HRV-associated illnesses. This finding suggests that there are underlying susceptibility factors for HRV-associated illness severity that are strongly linked with asthma susceptibility. Because HRV is the virus most commonly associated with acute asthma exacerbations in children, future reports from this cohort as longer-term outcomes, such as recurrent wheezing and asthma, are identified will help to clarify the complex relationship between host susceptibility and HRV infection.

Clinical implications.

Maternal atopy is a risk factor for severe rhinovirus-associated illness in infants, suggesting that there are underlying susceptibility factors for HRV-associated illness severity that are strongly linked with asthma susceptibility.

Acknowledgments

We thank the families enrolled in the Tennessee Children’s Respiratory Initiative.

Footnotes

Supported by KL2 RR24977-03 (to E.K.M.), a Thrasher New Investigator Award (to E.K.M.), a Thrasher Research Fund Clinical Research Grant (to T.V.H.), an NIH midcareer investigator award K24 AI 077930 (to T.V.H.), UL1 RR024975 (Vanderbilt CTSA), and an NIHK01 AI070808 mentored clinical science award (to K.N.C.). T.V.H. is also supported by NIH grants U01 HL 072471, R01 AI 05884, R01 HS018454, R01 HS019669, and NIH K12 ES 015855.

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: E. K. Miller has received research support from Thrasher and VCTRS K12 and is a member of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology’s EORD Committee. J. V. Williams has served as a consultant for MedImmune and Novartis and serves on the scientific advisory board for Quidel. K. N. Carroll has received research support from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)/National Institutes of Health (NIH). W. D. Dupont has received research support from the NIH. T. V. Hartert is on the Scientific Advisory Committee, is a speaker for Merck, and has received research support from MedImmune and the NIH. The rest of the authors have declared that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Miller E.K., Edwards K.M., Weinberg G.A., Iwane M.K., Griffin M.R., Hall C.B. A novel group of rhinoviruses is associated with asthma hospitalizations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.10.007. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferreira A., Williams Z., Donninger H., van Schalkwyk E.M., Bardin P.G. Rhinovirus is associated with severe asthma exacerbations and raised nasal interleukin-12. Respiration. 2002;69:136–142. doi: 10.1159/000056316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gern J.E. Rhinovirus respiratory infections and asthma. Am J Med. 2002;112(suppl 6A):19S–27S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)01060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayden F.G. Rhinovirus and the lower respiratory tract. Rev Med Virol. 2004;14:17–31. doi: 10.1002/rmv.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jartti T., Lehtinen P., Vuorinen T., Osterback R., van den Hoogen B., Osterhaus A.D. Respiratory picornaviruses and respiratory syncytial virus as causative agents of acute expiratory wheezing in children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1095–1101. doi: 10.3201/eid1006.030629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kotaniemi-Syrjanen A., Vainionpaa R., Reijonen T.M., Waris M., Korhonen K., Korppi M. Rhinovirus-induced wheezing in infancy—the first sign of childhood asthma? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:66–71. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papadopoulos N.G., Papi A., Psarras S., Johnston S.L. Mechanisms of rhinovirus-induced asthma. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2004;5:255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan W.C. Viruses in asthma exacerbations. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2005;11:21–26. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000146781.11092.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thumerelle C., Deschildre A., Bouquillon C., Santos C., Sardet A., Scalbert M. Role of viruses and atypical bacteria in exacerbations of asthma in hospitalized children: a prospective study in the Nord-Pas de Calais region (France) Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003;35:75–82. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lemanske R.F., Jr., Jackson D.J., Gangnon R.E., Evans M.D., Li Z., Shult P.A. Rhinovirus illnesses during infancy predict subsequent childhood wheezing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:571–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson D.J., Gangnon R.E., Evans M.D., Roberg K.A., Anderson E.L., Pappas T.E. Wheezing rhinovirus illnesses in early life predict asthma development in high-risk children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:667–672. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-309OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kusel M.M., de Klerk N.H., Kebadze T., Vohma V., Holt P.G., Johnston S.L. Early-life respiratory viral infections, atopic sensitization, and risk of subsequent development of persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1105–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.12.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller E.K., Khuri-Bulos N., Williams J.V., Shehabi A.A., Faouri S., Al Jundi I. Human rhinovirus C associated with wheezing in hospitalised children in the Middle East. J Clin Virol. 2009;46:85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Midulla F., Scagnolari C., Bonci E., Pierangeli A., Antonelli G., De Angelis D. Respiratory syncytial virus, human bocavirus and rhinovirus bronchiolitis in infants. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:35–41. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.153361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller E.K., Lu X., Erdman D.D., Poehling K.A., Zhu Y., Griffin M.R. Rhinovirus-associated hospitalizations in young children. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:773–781. doi: 10.1086/511821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shay D.K., Holman R.C., Newman R.D., Liu L.L., Stout J.W., Anderson L.J. Bronchiolitis-associated hospitalizations among US children, 1980-1996. JAMA. 1999;282:1440–1446. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh A.M., Moore P.E., Gern J.E., Lemanske R.F., Jr., Hartert T.V. Bronchiolitis to asthma: a review and call for studies of gene-virus interactions in asthma causation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:108–119. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200603-435PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Camara A.A., Silva J.M., Ferriani V.P., Tobias K.R., Macedo I.S., Padovani M.A. Risk factors for wheezing in a subtropical environment: role of respiratory viruses and allergen sensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheuk D.K., Tang I.W., Chan K.H., Woo P.C., Peiris M.J., Chiu S.S. Rhinovirus infection in hospitalized children in Hong Kong: a prospective study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:995–1000. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181586b63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Copenhaver C.C., Gern J.E., Li Z., Shult P.A., Rosenthal L.A., Mikus L.D. Cytokine response patterns, exposure to viruses, and respiratory infections in the first year of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:175–180. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200312-1647OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lau S.K., Yip C.C., Tsoi H.W., Lee R.A., So L.Y., Lau Y.L. Clinical features and complete genome characterization of a distinct human rhinovirus (HRV) genetic cluster, probably representing a previously undetected HRV species, HRV-C, associated with acute respiratory illness in children. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3655–3664. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01254-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McErlean P., Shackelton L.A., Andrews E., Webster D.R., Lambert S.B., Nissen M.D. Distinguishing molecular features and clinical characteristics of a putative new rhinovirus species, human rhinovirus C (HRV C) PLoS One. 2008;3:e1847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McErlean P., Shackelton L.A., Lambert S.B., Nissen M.D., Sloots T.P., Mackay I.M. Characterisation of a newly identified human rhinovirus, HRV-QPM, discovered in infants with bronchiolitis. J Clin Virol. 2007;39:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calvo C., Casas I., Garcia-Garcia M.L., Pozo F., Reyes N., Cruz N. Role of rhinovirus C respiratory infections in sick and healthy children in Spain. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:717–720. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181d7a708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piotrowska Z., Vazquez M., Shapiro E.D., Weibel C., Ferguson D., Landry M.L. Rhinoviruses are a major cause of wheezing and hospitalization in children less than 2 years of age. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:25–29. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181861da0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linsuwanon P., Payungporn S., Samransamruajkit R., Posuwan N., Makkoch J., Theanboonlers A. High prevalence of human rhinovirus C infection in Thai children with acute lower respiratory tract disease. J Infect. 2009;59:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Louie J.K., Roy-Burman A., Guardia-Labar L., Boston E.J., Kiang D., Padilla T. Rhinovirus associated with severe lower respiratory tract infections in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:337–339. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31818ffc1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han T.H., Chung J.Y., Hwang E.S., Koo J.W. Detection of human rhinovirus C in children with acute lower respiratory tract infections in South Korea. Arch Virol. 2009;154:987–991. doi: 10.1007/s00705-009-0383-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Renwick N., Schweiger B., Kapoor V., Liu Z., Villari J., Bullmann R. A recently identified rhinovirus genotype is associated with severe respiratory-tract infection in children in Germany. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1754–1760. doi: 10.1086/524312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan B.H., Loo L.H., Lim E.A., Kheng Seah S.L., Lin R.T., Tee N.W. Human rhinovirus group C in hospitalized children, Singapore. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1318–1320. doi: 10.3201/eid1508.090321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee W.M., Kiesner C., Pappas T., Lee I., Grindle K., Jartti T. A diverse group of previously unrecognized human rhinoviruses are common causes of respiratory illnesses in infants. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hartert T.V., Carroll K., Gebretsadik T., Woodward K., Minton P. The Tennessee Children’s Respiratory Initiative: objectives, design and recruitment results of a prospective cohort study investigating infant viral respiratory illness and the development of asthma and allergic diseases. Respirology. 2010;15:691–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01743.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goebel J., Estrada B., Quinonez J., Nagji N., Sanford D., Boerth R.C. Prednisolone plus albuterol versus albuterol alone in mild to moderate bronchiolitis. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2000;39:213–220. doi: 10.1177/000992280003900404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tal A., Bavilski C., Yohai D., Bearman J.E., Gorodischer R., Moses S.W. Dexamethasone and salbutamol in the treatment of acute wheezing in infants. Pediatrics. 1983;71:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams J.V., Wang C.K., Yang C.F., Tollefson S.J., House F.S., Heck J.M. The role of human metapneumovirus in upper respiratory tract infections in children: a 20-year experience. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:387–395. doi: 10.1086/499274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Erdman D.D., Weinberg G.A., Edwards K.M., Walker F.J., Anderson B.C., Winter J. GeneScan reverse transcription-PCR assay for detection of six common respiratory viruses in young children hospitalized with acute respiratory illness. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:4298–4303. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.9.4298-4303.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weinberg G.A., Erdman D.D., Edwards K.M., Hall C.B., Walker F.J., Griffin M.R. Superiority of reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction to conventional viral culture in the diagnosis of acute respiratory tract infections in children. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:706–710. doi: 10.1086/381456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu X., Holloway B., Dare R.K., Kuypers J., Yagi S., Williams J.V. Real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay for comprehensive detection of human rhinoviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:533–539. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01739-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khuri-Bulos N., Williams J.V., Shehabi A.A., Faouri S., Jundi E.A., Abushariah O. Burden of respiratory syncytial virus in hospitalized infants and young children in Amman, Jordan. Scand J Infect Dis. 2010;42:368–374. doi: 10.3109/00365540903496544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Talbot H.K., Crowe J.E., Jr., Edwards K.M., Griffin M.R., Zhu Y., Weinberg G.A. Coronavirus infection and hospitalizations for acute respiratory illness in young children. J Med Virol. 2009;81:853–856. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Talbot H.K., Shepherd B.E., Crowe J.E., Jr., Griffin M.R., Edwards K.M., Podsiad A.B. The pediatric burden of human coronaviruses evaluated for twenty years. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:682–687. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31819d0d27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Talbot H.K., Williams J.V., Zhu Y., Poehling K.A., Griffin M.R., Edwards K.M. Failure of routine diagnostic methods to detect influenza in hospitalized older adults. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:683–688. doi: 10.1086/653202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams J.V., Crowe J.E., Jr., Enriquez R., Minton P., Peebles R.S., Jr., Hamilton R.G. Human metapneumovirus infection plays an etiologic role in acute asthma exacerbations requiring hospitalization in adults. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1149–1153. doi: 10.1086/444392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams J.V., Tollefson S.J., Heymann P.W., Carper H.T., Patrie J., Crowe J.E. Human metapneumovirus infection in children hospitalized for wheezing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1311–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khuri-Bulos N., Williams J.V., Shehabi A.A., Faouri S., Al Jundi E., Abushariah O. Burden of respiratory syncytial virus in hospitalized infants and young children in Amman, Jordan. Scand J Infect Dis. 2010;42:368–374. doi: 10.3109/00365540903496544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Savolainen C., Blomqvist S., Mulders M.N., Hovi T. Genetic clustering of all 102 human rhinovirus prototype strains: serotype 87 is close to human enterovirus 70. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:333–340. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-2-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tamura K., Dudley J., Nei M., Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ledford R.M., Patel N.R., Demenczuk T.M., Watanyar A., Herbertz T., Collett M.S. VP1 sequencing of all human rhinovirus serotypes: insights into genus phylogeny and susceptibility to antiviral capsid-binding compounds. J Virol. 2004;78:3663–3674. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3663-3674.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Savolainen C., Mulders M.N., Hovi T. Phylogenetic analysis of rhinovirus isolates collected during successive epidemic seasons. Virus Res. 2002;85:41–46. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(02)00016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heymann P.W., Carper H.T., Murphy D.D., Platts-Mills T.A., Patrie J., McLaughlin A.P. Viral infections in relation to age, atopy, and season of admission among children hospitalized for wheezing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kusel M.M., de Klerk N.H., Holt P.G., Kebadze T., Johnston S.L., Sly P.D. Role of respiratory viruses in acute upper and lower respiratory tract illness in the first year of life: a birth cohort study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:680–686. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000226912.88900.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miron D., Srugo I., Kra-Oz Z., Keness Y., Wolf D., Amirav I. Sole pathogen in acute bronchiolitis: is there a role for other organisms apart from respiratory syncytial virus? Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:e7–e10. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181c2a212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Calvo C., Pozo F., Garcia-Garcia M., Sanchez M., Lopez-Valero M., Perez-Brena P. Detection of new respiratory viruses in hospitalized infants with bronchiolitis: a three-year prospective study. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:883–887. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01714.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Korppi M., Kotaniemi-Syrjanen A., Waris M., Vainionpaa R., Reijonen T.M. Rhinovirus-associated wheezing in infancy: comparison with respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:995–999. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000143642.72480.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnston S.L. Natural and experimental rhinovirus infections of the lower respiratory tract. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:S46–S52. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/152.4_Pt_2.S46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wark P.A., Johnston S.L., Bucchieri F., Powell R., Puddicombe S., Laza-Stanca V. Asthmatic bronchial epithelial cells have a deficient innate immune response to infection with rhinovirus. J Exp Med. 2005;201:937–947. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arden K.E., McErlean P., Nissen M.D., Sloots T.P., Mackay I.M. Frequent detection of human rhinoviruses, paramyxoviruses, coronaviruses, and bocavirus during acute respiratory tract infections. J Med Virol. 2006;78:1232–1240. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Briese T., Renwick N., Venter M., Jarman R.G., Ghosh D., Kondgen S. Global distribution of novel rhinovirus genotype. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:944–947. doi: 10.3201/eid1406.080271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khetsuriani N., Lu X., Teague W.G., Kazerouni N., Anderson L.J., Erdman D.D. Novel human rhinoviruses and exacerbation of asthma in children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1793–1796. doi: 10.3201/eid1411.080386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kistler A., Avila P.C., Rouskin S., Wang D., Ward T., Yagi S. Pan-viral screening of respiratory tract infections in adults with and without asthma reveals unexpected human coronavirus and human rhinovirus diversity. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:817–825. doi: 10.1086/520816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lamson D., Renwick N., Kapoor V., Liu Z., Palacios G., Ju J. MassTag polymerase-chain-reaction detection of respiratory pathogens, including a new rhinovirus genotype, that caused influenza-like illness in New York State during 2004-2005. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1398–1402. doi: 10.1086/508551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mackay I.M., Lambert S.B., McErlean P.K., Faux C.E., Arden K.E., Nissen M.D. Prior evidence of putative novel rhinovirus species, Australia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1823–1825. doi: 10.3201/eid1411.080725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arden K.E., Mackay I.M. Newly identified human rhinoviruses: molecular methods heat up the cold viruses. Rev Med Virol. 2010;20:156–176. doi: 10.1002/rmv.644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lau S.K., Yip C.C., Lin A.W., Lee R.A., So L.Y., Lau Y.L. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of human rhinovirus C in children and adults in Hong Kong reveals a possible distinct human rhinovirus C subgroup. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1096–1103. doi: 10.1086/605697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]