Summary

Hypertension affects more than 1.5 billion people worldwide but the precise cause of elevated blood pressure (BP) cannot be determined in most affected individuals. Nonetheless, blockade of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) lowers BP in the majority of patients with hypertension. Despite its apparent role in hypertension pathogenesis, the key cellular targets of the RAS that control BP have not been clearly identified. Here we demonstrate that RAS actions in the epithelium of the proximal tubule have a critical and non-redundant role in determining the level of BP. Abrogation of AT1 angiotensin receptor signaling in the proximal tubule alone is sufficient to lower BP, despite intact vascular responses. Elimination of this pathway reduces proximal fluid reabsorption and alters expression of key sodium transporters, modifying pressure-natriuresis and providing substantial protection against hypertension. Thus, effectively targeting epithelial functions of the proximal tubule of the kidney should be a useful therapeutic strategy in hypertension.

Introduction

Among the regulatory systems for blood pressure (BP), the RAS has a dominant role (Le et al., 2008). Pathological activation of the RAS is a common contributor to hypertension in humans as RAS antagonists lower BP in the majority of patients with essential hypertension (Matchar et al., 2008). The actions of the RAS to increase BP are primarily mediated by activation of type 1 (AT1) angiotensin receptors. AT1 receptors are expressed in a number of tissues where they have a potential to affect BP including the CNS, heart, vasculature, kidney, and adrenal gland (Le et al., 2008), but it has been difficult to identify the critical tissue targets of the RAS in hypertension pathogenesis.

Recent studies have implicated vascular signaling pathways as key contributors to BP regulation and development of hypertension (Guilluy et al. 2010; Heximer et al., 2003; Michael et al., 2008; Wirth et al., 2008). On the other hand, the work of Guyton and colleagues (Guyton, 1991), human genetic studies by the Lifton laboratory (Lifton et al., 2001), and our recent studies in mice (Coffman and Crowley, 2008) have suggested that renal excretory function is a major determinant of intra-arterial pressure. In the kidney, AT1 receptors are expressed in epithelial cells along the nephron (Bouby et al., 1997). Among populations of renal epithelia, AT1 receptors in the proximal tubule may have special relevance to BP homeostasis since: this segment is responsible for reabsorption of a sizeable fraction of the glomerular filtrate (Weinstein, 2008), it contains all of the components of the RAS under independent local control (Kobori et al., 2007; Navar et al., 2002), and RAS activation is known to influence its handling of solutes and fluid (Cogan, 1990). Nonetheless, while direct actions of angiotensin II in the proximal tubule were first identified more than 25 years ago (Schuster et al., 1984), their impact on regulation of BP in the intact animal has never been clearly defined. Here we demonstrate potent actions of AT1 receptors in renal proximal tubule to regulate BP homeostasis.

Results

Reduced BP in mice lacking AT1A receptors in the renal proximal tubule

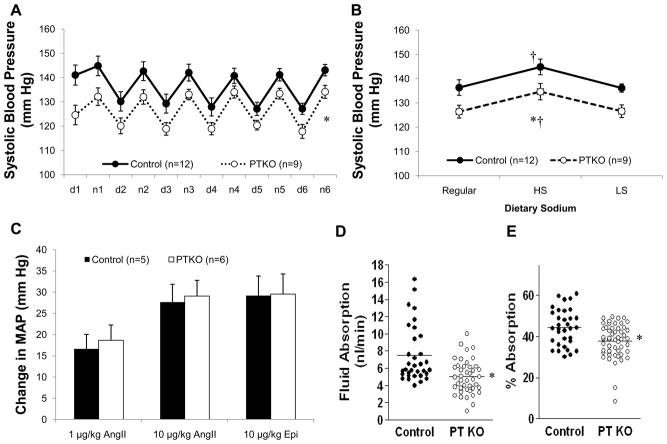

We crossed mice with a conditional Agtr1a allele (Figure S1) with a Pepck-Cre transgenic mouse line expressing Cre in proximal but not distal nephron segments (Rankin et al., 2006) (Figure S2A, B) to generate mice lacking AT1A receptors only in the renal proximal tubule (PTKO). As shown in Figure 1A, systolic BPs, measured by radiotelemetry were significantly lower in PTKOs (126±3 mm Hg) than littermate controls (136±3 mm Hg; p=0.03). This difference was apparent both during the day (120±3 vs. 130±3 mm Hg; p=0.003) and at night (133±3 vs. 142±3 mm Hg; p=0.04). Mice were then sequentially fed high (6% NaCl) and low (<0.002% NaCl) salt diets while their BPs were monitored. As shown in Figure 1B, BPs increased significantly and to a similar extent in both groups during high salt feeding and returned to baseline levels when the low salt diet was instituted, consistent with the phenotype of sodium-sensitivity previously reported in 129 mice (Francois et al., 2005); the magnitude of BP difference between the PTKOs and controls remained constant across the different dietary sodium intakes.

Figure 1. Baseline studies in PTKO mice.

(A) 12-hour mean systolic BPs during the day (d) and at night (n) on a control diet. Systolic BPs were significantly lower in PTKO mice compared to controls (*p=0.03). (B) BPs increased significantly (†p<0.01) and to a similar extent in PTKO and controls during high salt (6% NaCl) feeding and returned to baseline values on low salt (<0.02% NaCl). BPs were significantly lower in the PTKOs throughout the experiment (*p<0.044). (C) The maximal increases in mean arterial pressure (MAP) compared to baseline in response to bolus infusions of angiotensin II (1 and 10 μg/kg) or epinephrine (10 μg/kg) were identical between PTKOs and controls. (D) Rates of fluid reabsorption by the renal PT measured in vivo using standard free flow micropuncture were significantly reduced in the PTKO mice compared to controls as an absolute rate (p=0.00011) or (F) when adjusted for single-nephron glomerular filtration rate (p=0.0007). Error bars represent SEM.

To exclude the possibility that vascular responses mediated by AT1 receptors might be affected in the PTKOs, we assessed acute pressor responses to angiotensin II in vivo as described previously (Ito et al., 1995). As shown in Figure 1C, acute infusion of angiotensin II caused marked vasoconstriction and the magnitude of the vasoconstrictor responses was virtually identical in both groups.

AT1A receptors in the proximal tubule control fluid reabsorption

To determine whether deletion of AT1A receptors would affect fluid handling in the proximal tubule, we examined nephron function using free-flow micropuncture (Hashimoto et al., 2005). As shown in Table 1 and Figure 1D, absolute rates of proximal fluid reabsorption (4.76±0.32 vs. 7.5±0.58 nl/min; p=0.00014) were significantly reduced in the PTKOs compared to controls. Single nephron GFRs measured in the proximal tubule were also significantly lower in the PTKOs (13 ± 0.61 nl/min) than controls (16.54 ± 0.81 nl/min; p=0.001), consistent with the whole animal values (Table 1). Nonetheless, when corrected for SNGFR, fractional reabsorption rates in proximal tubule were also significantly lower in the PTKOs (36.5±1.5%) than controls (44.5±1.6 %; p=0.0005, Figure 1E). Thus, loss of AT1A receptors from the proximal tubule leads to a reduction in fluid reabsorption, indicating a tonic role for the RAS to control fluid reabsorption by proximal tubule epithelia in vivo.

Table 1.

Physiological Data

| Control (n=8) | PT KO (n=7) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g) | 32.4 ± 1.73 | 30 ± 1.54 | ns |

| Kidney weight (mg) | 435.4 ± 19.8 | 410 ± 22.1 | ns |

| Glomerular Filtration Rate, GFR (μL/min) | 620±49 | 439±58 | 0.025 |

| U osm (mOsm/kgH2O) | 2441.4 ± 103 | 2165 ± 102 | 0.15 |

| UV (μl/min) | 1.5 ± 0.08 | 2.1 ± 0.17 | 0.005 |

| Proximal Tubule Micropuncture | |||

| TF/P iothal | 1.85 ± 0.05 | 1.6 ± 0.03 | 0.0002 |

| Absorption (nl/min) | 7.5 ± 0.58 | 4.76 ± 0.32 | 0.000 |

| Fractional Abs (%) | 44.45 ± 1.57 | 36.5 ± 1.53 | 0.0005 |

Data represent values ± SEM.

PTKO mice are protected against hypertension

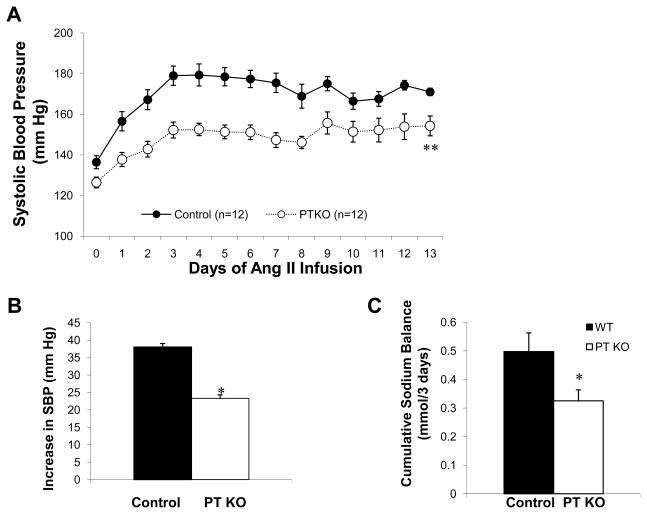

To determine the contribution of AT1A receptors in the proximal tubule to the development of hypertension, we infused PTKO and controls mice with angiotensin II (1000 ng/kg/min) by osmotic mini-pump. As shown in Figure 2A, the control group developed robust hypertension with a mean systolic BP of 172±4 mm Hg, which was significantly higher than that of the PTKOs (150±4 mm Hg; p=0.0005). A similar difference was observed comparing the mean increase in BPs in the controls (38±5 mm Hg) with the PTKOs (23±3 mm Hg; p=0.0005) (Figure 2B). Thus, deletion of AT1A receptors from the proximal tubule conveyed substantial protection against hypertension. As shown in Figure 2C, the extent of positive sodium balance was significantly reduced in PTKOs (0.33±0.04 mmol) compared to controls (0.50±0.07 mmol; p=0.046), consistent with facilitated natriuresis as a mechanism for their resistance to hypertension.

Figure 2. AT1A receptors in the proximal tubule promote hypertension.

(A) With infusion of ang II (1000ng/kg/min), BPs increased significantly in both control and PTKO mice but the hypertensive response to angiotensin II was significantly attenuated in the PTKOs (**p<0.001). (B) The mean increase in BP during the angiotensin II infusion was significantly less in the PTKOs (23±3 mm Hg) compared to controls (black bars; 38±5 mm Hg, *p=0.0005). (C) Cumulative sodium balance was significantly lower in the PTKOs (n=8) than controls (n=7, *p=0.046) during the first 3 days of ang II infusion. Error bars represent SEM.

Control of renal sodium transporters by AT1A receptors in proximal tubule

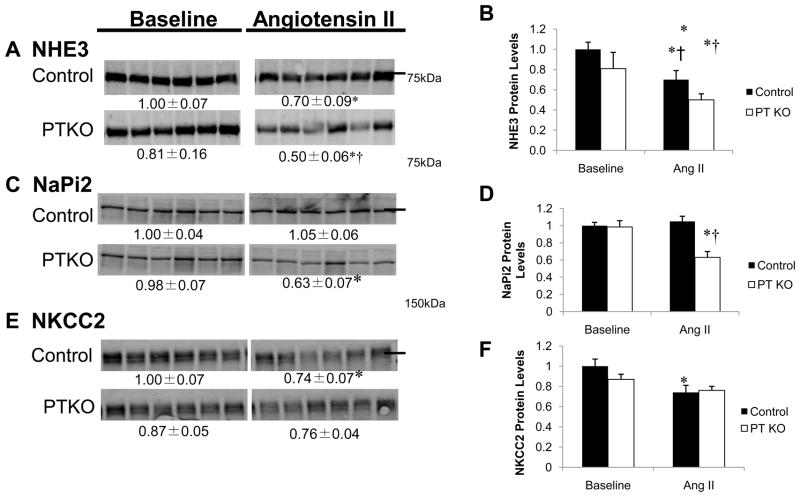

To examine the molecular mechanisms responsible for the attenuated hypertension and enhanced pressure natriuresis in PTKOs, we measured abundance of key sodium transporters along the nephron (Figure 3). At baseline, there were no differences in abundance of any of these transporters between PTKOs and controls. However, during angiotensin II infusion, significant differences in pool sizes of key transporters were uncovered. In control mice, abundance of the sodium-proton antiporter 3 (NHE3), the major sodium transporter in the proximal tubule, fell by ≈30% during angiotensin II infusion (Figure 3A and B). By contrast, in the PTKOs, abundance of NHE3 fell by more than 50% (Figures 3A and B) to levels that were significantly lower than controls (0.50±0.06 vs. 0.70±0.09; p=0.01). In control mice, levels of the sodium phosphate co-transporter (NaPi2), were unaffected by angiotensin II infusion (Figure 3C and D), whereas NaPi2 protein levels decreased by ≈36% in the PTKOs (p=0.005).

Figure 3. Abundance of Sodium Transporters in Control and PTKO mice.

Protein levels of key transporters in kidneys of PTKO and control mice including NHE3 (A, B), NaPi2 (C,D), and NKCC2 (E, F) were measured by western blot. Numbers below the blots indicate the mean ± S.E.M of the sample density normalized to the control baseline set (arbitrarily defined as 1.0). The densitometry data are in bar graphs (B, D, and F) where * indicates p<0.05.

Abundances of the sodium-potassium-two-chloride co-transporter (NKCC2), a major sodium transporter downstream in the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle, were equivalent at baseline in the two experimental groups (Figure 3), and fell to a similar extent during angiotensin II infusion (Figure 3E and F). Similarly, total protein abundance of the β subunit epithelial sodium channel (ENaCβ), expressed from late distal nephron through collecting ducts, and the α1 subunit of the sodium-potassium ATPase (Na,K-ATPase), expressed all along the nephron, were unaffected in PTKO mice (Figure S3A, B).

Discussion

The importance of AT1 angiotensin receptors in clinical medicine is highlighted by the impressive cardiovascular benefits of angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs). As anti-hypertensive agents, these drugs are effective and well tolerated (Matchar et al., 2008), ameliorating morbidity and mortality associated with cardiovascular diseases (Pfeffer et al., 2003) (Brenner et al., 2001; Lewis et al., 2001; Yusuf et al., 2008). By inference, these clinical studies indicate powerful contributions of AT1 receptors to the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and kidney damage. However, the specific cellular targets responsible for their pathological actions cannot be identified from studies using pharmacological inhibitors that block AT1 receptors in all tissues.

The kidney has been suggested play a predominant role in BP control. Guyton hypothesized that the substantial capacity of the kidney to excrete sodium provides a compensatory system of virtually infinite gain to oppose processes, including increases in peripheral vascular resistance, which would tend to increase BP (Guyton, 1991). This hypothesis is supported by the genetic studies of Lifton and associates linking Mendelian disorders impacting BP homeostasis to genetic variants affecting salt and water handling by the kidney (Lifton et al., 2001). On the other hand, a series of recent studies have suggested that vascular dysfunction alone may be sufficient to cause hypertension (Guilluy et al.; Heximer et al., 2003; Michael et al., 2008; Wirth et al., 2008). For example, studies by Guilluy and associates indicate that elimination of Arhgef1, a Rho exchange factor linked to AT1 receptor signaling, from smooth muscle apparently results in a complete abrogation of hypertension (Guilluy et al., 2010).

In previous studies using renal cross-transplantation, we found distinct and significant roles for AT1A receptor actions in both the kidney and extra-renal tissues to BP homeostasis (Crowley et al., 2005). In hypertension, however, receptors inside the kidney played the dominant role, driving elevations in BP as well as the development of cardiac hypertrophy (Crowley et al., 2006). This was due to direct actions of AT1 receptors in the renal parenchyma, independent of aldosterone. Within the kidney, AT1 receptors are widely expressed in vasculature, in glomeruli, and by populations of epithelial cells across the nephron (Bouby et al., 1997). Activation of AT1 receptors at any or all of these sites could potentially impact BP regulation.

Actions of angiotensin II to influence solute transport along the nephron have been well documented (Barreto-Chaves and Mello-Aires, 1996; Cogan, 1990; Geibel et al., 1990; Levine et al., 1996; Peti-Peterdi et al., 2002; Quan and Baum, 1998; Schuster et al., 1984; Wang et al., 1996). We considered that the population of AT1 receptor in the proximal tubule may directly impact BP regulation since the major portion of the glomerular filtrate is reabsorbed here (Weinstein, 2008) and sodium transport by the proximal tubule may be a major determinant of the pressure-natriuresis response (McDonough et al., 2003). Furthermore, studies by Navar and Kobori have suggested that the proximal tubule is a key site of an independently regulated intra-renal RAS serving as a source of angiotensinogen and angiotensin II, which may influence nephron function (Kobori et al., 2007; Navar et al., 2002). The capacity for angiotensinogen generated in the proximal tubule to affect blood pressure was shown by Sigmund and associates in studies using transgenic mice expressing human angiotensinogen and renin specifically in proximal tubule (Lavoie et al., 2004). On the other hand, it has been suggested that the final adjustments of urinary sodium excretion in the distal nephron are also important for body fluid volume homeostasis (Meneton et al., 2004). In this regard, most of the human mutations with effects upon BP affect fluid reabsorption in the distal portion of the nephron (Lifton et al., 2001).

We generated mice with specific deletion of AT1A receptors from epithelial cells in the proximal tubule using the well-characterized PEPCK-Cre mouse line, which induces excision of floxed alleles from epithelial cells in the proximal but not distal tubule (Higgins et al., 2007; Rankin et al., 2006). We find that elimination of AT1A receptors from proximal tubule causes a significant reduction of baseline BP by ≈10 mm Hg. Notwithstanding recent reports of dominant actions of vascular signaling in BP control (Guilluy et al.; Heximer et al., 2003; Michael et al., 2008; Wirth et al., 2008), the low BPs in the PTKOs occurred despite intact constrictor responses to angiotensin II in the peripheral vasculature. This non-redundant role for AT1 receptors in proximal tubule to determine BP level also suggests there is tonic stimulation of these receptors in the basal, euvolemic state consistent with previous studies showing that acute administration of specific AT1 receptor blockers to rats inhibits net proximal reabsorption (Thomson et al., 2006; Xie et al., 1990). Similarly, we find that elimination of AT1A receptors from proximal tubule also reduces rates of fluid reabsorption.

Agtr1a−/− mice with global deletion of AT1A receptors have exaggerated fluctuations in BP with extremes of dietary sodium intake (sodium sensitivity) (Oliverio et al., 2000). Enhanced sodium sensitivity is associated with absence of AT1A receptors from the kidney, whereas elimination of receptors only from extra-renal tissues does not affect this response (Crowley et al., 2005). Despite their lower basal BPs, the magnitude of BP changes during high and low salt feeding was very similar in PTKOs and controls (Figure 1C). Thus, deletion of AT1A receptors from the proximal tubule alone is not sufficient to generate a phenotype of enhanced sodium sensitivity, indicating that AT1 receptors pools at other sites, perhaps the distal nephron or renal vasculature, may control this response.

We find that elimination of AT1 receptors from proximal tubule provides significant protection against angiotensin II-dependent hypertension, identifying this epithelial compartment as a target of the RAS that is critical to the pathogenesis of hypertension. Protection from hypertension is associated with enhanced natriuresis and altered sodium balance, suggesting that modulation of sodium handling is critical for these actions. As discussed above, activation of AT1 receptors stimulates fluid reabsorption in proximal tubules (Schuster et al., 1984; Cogan, 1990) by triggering coordinate stimulation of the luminal sodium-proton anti-porter (NHE3) along with the basolateral sodium-potassium ATPase (Cogan, 1990; Geibel et al., 1990). Levels and localization of key sodium transporters in the proximal tubule are modified during ACE inhibition, suggesting control of their synthesis and cell trafficking by angiotensin II (Yang et al., 2007).

We examined the contributions of AT1 receptors in the proximal tubule in isolation to regulate abundance of key sodium transporters in vivo in the intact animal. Under basal conditions, there were no statistically significant differences in major transporter abundance between the groups, although the levels of NHE3 tended to be lower in the PTKOs. In this setting, the PTKO animals are in balance and their urinary excretion of sodium reflects dietary intake. Therefore, it follows that their transporter profiles would not differ dramatically from controls. Further, because of their reduced BPs and GFR, hemodynamic factors such as changes in peritubular capillary pressures may also influence sodium reabsorption in the PTKOs independent of absolute levels of epithelial transporters. By contrast, the regulation of luminal transporters by AT1A receptors in proximal tubule is clearly revealed when the steady state is abruptly modified during chronic infusion of angiotensin II. With angiotensin II infusion, there was a significant reduction in NHE3 within the control group, compared to baseline. Such attenuation of NHE3 expression in response to BP elevation has been described previously (McDonough et al., 2003), and may be one mechanism facilitating natriuresis as pressure increases. The further and significant reduction in NHE3 levels in the PTKOs compared to controls is consistent with a lower threshold for pressure natriuresis in these mice, supported by the differences we observed in net sodium balance (Figure 2C). We also found that NaPi2 expression during angiotensin II infusion is regulated by AT1A receptors in the proximal tubule (Figure 3). Taken together, these findings provide clear evidence for actions of AT1A receptors in the proximal tubule to oppose adaptive reductions in key sodium transporters in the proximal tubule during hypertension, with the net effect of impairing the pressure natriuresis response (Magyar and McDonough, 2000). When this pathway is eliminated, the hypertensive response in is attenuated (Figure 2A, B), highlighting the power of mechanisms controlling renal solute reabsorption in the proximal tubule to determine BP levels.

In summary, our studies show that the epithelium of the proximal tubule is a critical location for integrating signals to set the level of intra-arterial pressure. This is accomplished though modulation of tubular fluid reabsorption and regulated expression of sodium transporter proteins. The RAS provides tonic control of this pathway supporting BP independent of its vascular actions. Furthermore, it is likely that other neuro-hormonal systems exploit these proximal tubular mechanisms for physiological control (DiBona, 2005; Zeng et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009). Our data suggest that effective inhibition of sodium reabsorption in the renal proximal tubule could be a useful therapeutic strategy in hypertension, supplementing the range of diuretic agents currently used to target sodium reabsorption in distal nephron segments. Our studies further suggest that blockade of this pathway is likely a key component underlying the therapeutic efficacy of RAS antagonists in the treatment of hypertension.

Experimental Procedures

Animals

Inbred 129/SvEv mice with a conditional Agtr1a allele were generated as described in Supplemental Material. The Pepck-Cre transgene was back-crossed more than 10 generations onto the 129/SvEv background. Mice were bred and maintained in the animal facility at the Durham VA Medical Center according to NIH guidelines.

BP measurements in conscious mice

BPs were measured in conscious mice using radiotelemetry, as described previously (Crowley et al., 2005).

Sodium Balance Studies

Measurements of sodium balance were carried out as previously described (Crowley et al., 2006) with individual metabolic cages and a gel diet containing nutrients, water and 0.1% w/w sodium (Nutra-gel; Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ).

Micropuncture Studies

Mice were anesthetized and prepared for micropuncture studies as described previously (Hashimoto et al., 2005). To determine nephron filtration and absorption rates, 125I iothalamate (Glofil, Questcor Pharmaceuticals, Hayward, CA) was infused at ~40 μCi/hr. A blood sample was collected after 20–25 min of equilibration, and free flow micropuncture was performed.

Immunoblot Analysis

Levels of renal transporter proteins were determined as described previously (Yang et al., 2007). Kidneys were de-capsulated and individually homogenized, centrifuged, and supernatant “homogenate” retained. A constant amount of homogenate protein from each animal was denatured, resolved on 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and transferred to a single polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore Immobilon-P). After blocking, blots were incubated with specific antibodies (listed in Supplemental Material). Sample amounts were determined to be in the linear range of detection, and signals were quantitated with the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR, Lincoln, NB). Data for each protein were normalized to the mean of expression in the control non-infused group defined as 1.0.

Statistical analysis

The values for each parameter within a group are expressed as the mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM). For comparisons between groups, statistical significance was assessed using ANOVA followed by unpaired t test adjusted for multiple comparisons (normally distributed data), and the Mann Whitney U test was employed for non-parametric data. For comparisons within groups, normally distributed variables were analyzed by a paired t test, whereas non-parametric analysis was with the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Normality was determined using the Shapiro-Wilk W test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical support of Robert C. Griffiths and Carrie L. Mach and funding from NIH (TMC 2R01 HL056122 13), AHA (SBG Fellow-to-Faculty Award 0475034N), VA Research Administration, and the Edna and Fred L. Mandel, Jr. Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barreto-Chaves ML, Mello-Aires M. Effect of luminal angiotensin II and ANP on early and late cortical distal tubule HCO3- reabsorption. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:F977–984. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.5.F977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouby N, Hus-Citharel A, Marchetti J, Bankir L, Corvol P, Llorens-Cortes C. Expression of type 1 angiotensin II receptor subtypes and angiotensin II-induced calcium mobilization along the rat nephron. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:1658–1667. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V8111658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, Remuzzi G, Snapinn SM, Zhang Z, Shahinfar S. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:861–869. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns KD, Inagami T, Harris RC. Cloning of a rabbit kidney cortex AT1 angiotensin II receptor that is present in proximal tubule epithelium. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:F645–654. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.264.4.F645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffman TM, Crowley SD. Kidney in hypertension: Guyton redux. Hypertension. 2008;51:811–816. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.105.063636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogan MG. Angiotensin II: a powerful controller of sodium transport in the early proximal tubule. Hypertension. 1990;15:451–458. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.15.5.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley SD, Gurley SB, Herrera MJ, Ruiz P, Griffiths R, Kumar AP, Kim HS, Smithies O, Le TH, Coffman TM. Angiotensin II causes hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy through its receptors in the kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17985–17990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605545103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley SD, Gurley SB, Oliverio MI, Pazmino AK, Griffiths R, Flannery PJ, Spurney RF, Kim HS, Smithies O, Le TH, Coffman TM. Distinct roles for the kidney and systemic tissues in blood pressure regulation by the renin-angiotensin system. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1092–1099. doi: 10.1172/JCI200523378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiBona GF. Dynamic analysis of patterns of renal sympathetic nerve activity: implications for renal function. Exp Physiol. 2005;90:159–161. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2004.029215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francois H, Athirakul K, Howell D, Dash R, Mao L, Kim HS, Rockman HA, Fitzgerald GA, Koller BH, Coffman TM. Prostacyclin protects against elevated blood pressure and cardiac fibrosis. Cell Metab. 2005;2:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geibel J, Giebisch G, Boron WF. Angiotensin II stimulates both Na(+)-H+ exchange and Na+/HCO3- cotransport in the rabbit proximal tubule. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:7917–7920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.7917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilluy C, Bregeon J, Toumaniantz G, Rolli-Derkinderen M, Retailleau K, Loufrani L, Henrion D, Scalbert E, Bril A, Torres RM, Offermanns S, Pacaud P, Loirand G. The Rho exchange factor Arhgef1 mediates the effects of angiotensin II on vascular tone and blood pressure. Nat Med. 16:183–190. doi: 10.1038/nm.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyton AC. Blood pressure control--special role of the kidneys and body fluids. Science. 1991;252:1813–1816. doi: 10.1126/science.2063193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto S, Adams JW, Bernstein KE, Schnermann J. Micropuncture determination of nephron function in mice without tissue angiotensin-converting enzyme. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F445–452. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00297.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heximer SP, Knutsen RH, Sun X, Kaltenbronn KM, Rhee M-H, Peng N, Oliveira-dos-Santos A, Penninger JM, Muslin AJ, Steinberg TH, Wyss JM, Mecham RP, Blumer KJ. Hypertension and prolonged vasoconstrictor signaling in RGS2-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:445–452. doi: 10.1172/JCI15598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DF, Kimura K, Bernhardt WM, Shrimanker N, Akai Y, Hohenstein B, Saito Y, Johnson RS, Kretzler M, Cohen CD, Eckardt KU, Iwano M, Haase VH. Hypoxia promotes fibrogenesis in vivo via HIF-1 stimulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3810–3820. doi: 10.1172/JCI30487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Oliverio MI, Mannon PJ, Best CF, Maeda N, Smithies O, Coffman TM. Regulation of blood pressure by the type 1A angiotensin II receptor gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3521–3525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobori H, Nangaku M, Navar LG, Nishiyama A. The intrarenal renin-angiotensin system: from physiology to the pathobiology of hypertension and kidney disease. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59:251–287. doi: 10.1124/pr.59.3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie JL, Lake-Bruse KD, Sigmund CD. Increased blood pressure in transgenic mice expressing both human renin and angiotensinogen in the renal proximal tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F965–971. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00402.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le T, Crowley S, Gurley S, Coffman T. The Kidney Physiology and Pathophysiology. Elsevier Inc; 2008. The Renin-Angiotensin System; pp. 343–357. [Google Scholar]

- Levine DZ, Iacovitti M, Buckman S, Burns KD. Role of angiotensin II in dietary modulation of rat late distal tubule bicarbonate flux in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:120–125. doi: 10.1172/JCI118378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, Berl T, Pohl MA, Lewis JB, Ritz E, Atkins RC, Rohde R, Raz I. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:851–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifton RP, Gharavi AG, Geller DS. Molecular mechanisms of human hypertension. Cell. 2001;104:545–556. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magyar CE, McDonough AA. Molecular mechanisms of sodium transport inhibition in proximal tubule during acute hypertension. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2000;9:149–156. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200003000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matchar DB, McCrory DC, LA O, Patel MR, Patel UD, Patwardhan MB, Powers B, Samsa GP, Gray RN. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers for treating essential hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:16–29. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-1-200801010-00189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough AA, Leong PK, Yang LE. Mechanisms of pressure natriuresis: how blood pressure regulates renal sodium transport. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;986:669–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneton P, Loffing J, Warnock DG. Sodium and potassium handling by the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron: the pivotal role of the distal and connecting tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;287:F593–601. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00454.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael SK, Surks HK, Wang Y, Zhu Y, Blanton R, Jamnongjit M, Aronovitz M, Baur W, Ohtani K, Wilkerson MK, Bonev AD, Nelson MT, Karas RH, Mendelsohn ME. High blood pressure arising from a defect in vascular function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6702–6707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802128105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navar L, Harrison-Bernard L, Nishiyama A, Kobori H. Regulation of intrarenal angiotensin II in hypertension. Hypertension. 2002;39:316–322. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.103821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliverio MI, Best CF, Smithies O, Coffman TM. Regulation of sodium balance and blood pressure by the AT(1A) receptor for angiotensin II. Hypertension. 2000;35:550–554. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.2.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peti-Peterdi J, Warnock DG, Bell PD. Angiotensin II directly stimulates ENaC activity in the cortical collecting duct via AT(1) receptors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1131–1135. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000013292.78621.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, Held P, McMurray JJ, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, Ostergren J, Yusuf S, Pocock S. Effects of candesartan on mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure: the CHARM-Overall programme. Lancet. 2003;362:759–766. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14282-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan A, Baum M. Endogenous angiotensin II modulates rat proximal tubule transport with acute changes in extracellular volume. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 1998;275:F74–78. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.275.1.F74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin EB, Tomaszewski JE, Haase VH. Renal cyst development in mice with conditional inactivation of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2576–2583. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster VL, Kokko JP, Jacobson HR. Angiotensin II directly stimulates sodium transport in rabbit proximal convoluted tubules. J Clin Invest. 1984;73:507–515. doi: 10.1172/JCI111237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson SC, Deng A, Wead L, Richter K, Blantz RC, Vallon V. An unexpected role for angiotensin II in the link between dietary salt and proximal reabsorption. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1110–1116. doi: 10.1172/JCI26092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang DH, Du Y, Yao A, Hu Z. Regulation of type 1 angiotensin II receptor and its subtype gene expression in kidney by sodium loading and angiotensin II infusion. J Hypertens. 1996;14:1409–1415. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199612000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein AM. Sodium and Chloride Transport: Proximal Nephron. In: Alpern R, Hebert SC, editors. The Kidney Physiology and Pathophysiology. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2008. pp. 793–847. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth A, Benyo Z, Lukasova M, Leutgeb B, Wettschureck N, Gorbey S, Orsy P, Horvath B, Maser-Gluth C, Greiner E, Lemmer B, Schutz G, Gutkind JS, Offermanns S. G12-G13-LARG-mediated signaling in vascular smooth muscle is required for salt-induced hypertension. Nat Med. 2008;14:64–68. doi: 10.1038/nm1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie MH, Liu FY, Wong P, Timmermans P, Cogan M. Proximal nephron and renal effects of DuP 753, a nonpeptide angiotensin II receptor antagonist. Kidney Int. 1990;38:473–479. doi: 10.1038/ki.1990.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang LE, Leong PK, McDonough AA. Reducing blood pressure in SHR with enalapril provokes redistribution of NHE3, NaPi2, and NCC and decreases NaPi2 and ACE abundance. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F1197–1208. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00040.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, Dyal L, Copland I, Schumacher H, Dagenais G, Sleight P, Anderson C. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1547–1559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng C, Villar VA, Yu P, Zhou L, Jose PA. Reactive oxygen species and dopamine receptor function in essential hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2009;31:156–178. doi: 10.1080/10641960802621283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang MZ, Yao B, Fang X, Wang S, Smith JP, Harris RC. Intrarenal dopaminergic system regulates renin expression. Hypertension. 2009;53:564–570. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.127035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.