Abstract

Background

There are limited population-based studies of determinants of physical therapy use for chronic low back pain (LBP) and of the types of treatments received by individuals who see a physical therapist.

Objective

The purposes of this study were: (1) to identify determinants of physical therapy use for chronic LBP, (2) to describe physical therapy treatments for chronic LBP, and (3) to compare use of treatments with current best evidence on care for this condition.

Design

This study was a cross-sectional, population-based telephone survey of North Carolinians.

Methods

Five hundred eighty-eight individuals with chronic LBP who had sought care in the previous year were surveyed on their health and health care use. Bivariate and multivariable analyses were conducted to identify predisposing, enabling, and need characteristics associated with physical therapy use. Descriptive analyses were conducted to determine the use of physical treatments for individuals who saw a physical therapist. Use of treatments was compared with evidence from systematic reviews.

Results

Of our sample, 29.7% had seen a physical therapist in the previous year, with a mean of 15.6 visits. In multivariable analyses, receiving workers' compensation, seeing physician specialists, and higher Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey questionnaire (SF-12) physical component scores were positively associated with physical therapy use. Having no health insurance was negatively associated with physical therapy use. Exercise was the most frequent treatment received (75% of sample), and traction was the least frequent treatment received (7%). Some effective treatments were underutilized, whereas some ineffective treatments were overutilized.

Limitations

Only one state was examined, and findings were based on patient report.

Conclusions

Fewer than one third of individuals with chronic LBP saw a physical therapist. Health-related and non–health-related factors were associated with physical therapy use. Individuals who saw a physical therapist did not always receive evidence-based treatments. There are potential opportunities for improving access to and quality of physical therapy for chronic LBP.

Low back pain (LBP) is one of the most common conditions managed by outpatient physical therapists.1,2 Considering current practice guidelines for acute LBP, which promote activity and the avoidance of passive interventions such as the application of heat and cold,3–5 patients with chronic LBP probably make up the majority of an outpatient physical therapist's LBP caseload. In an analysis of more than 29,000 patients with back and neck pain in the National Spine Network database, individuals who had had pain for more than 3 months (ie, chronic pain) were approximately 35% more likely to see a physical therapist than were those who had had pain for less than 3 months.6

Although patients with chronic LBP represent a large proportion of outpatient physical therapists' caseloads, few studies have specifically examined the use of physical therapy for the management of chronic LBP. We are unaware of any population-based studies conducted in the United States that have specifically examined determinants of physical therapy use for the management of chronic LBP and the types of treatments received by individuals who do see a physical therapist. Such information is useful for determining whether patients have adequate access to physical therapists and are receiving appropriate, high-quality care.

In a population-based study conducted in Canada, Lim et al7 found that 17.2% of individuals with chronic LBP had sought care from a physical therapist in the previous year. Individuals who were younger, female, more educated, and had a higher income were more likely to have seen a physical therapist. Pain with activity limitations also was predictive of physical therapy use. Although this study provides useful information on physical therapy use in Canada, differences in the Canadian and US health care systems limit its generalizability to the United States.

Feuerstein et al8 examined data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) and the National Medical Expenditure Survey (NMES, the predecessor to MEPS), both United States population-based surveys, and reported that the use of physical therapy for back problems increased from 5.0% in 1987 to 9.3% in 1997. They also found no statistically significant change in mean visits (10.4 in 1987 and 8.4 in 1997). Martin et al,9 in a more recent analysis of MEPS data, reported a 78% increase from 1997 to 2005 in inflation-adjusted physical therapy expenditures for the management of back and neck problems. They later attributed this finding to an increase in the prevalence of people who sought physical therapy care.10

Although the MEPS and NMES data are from the United States and are population-based, the questions for back pain are not specific in regard to duration and intensity and, therefore, encompass acute, subacute, and chronic problems. In addition, questions on health status and function are asked at predefined time points each year and may or may not coincide with the individuals' back problems. Finally, detailed questions on the types of physical therapy interventions delivered are not included. The usefulness of these surveys for understanding physical therapy care for chronic LBP, therefore, is limited.

Over the past 2 decades, we have witnessed an explosion in the number of randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews that have increased our understanding of appropriate care for chronic LBP. For example, in regard to interventions commonly delivered by physical therapists, current evidence indicates that exercise,11,12 therapeutic massage,11,13 and spinal manipulation11,14 are effective; traction is ineffective11,15; and the effectiveness of ultrasound, electrical stimulation, and heat or cold modalities is questionable or unclear.11,16,17 Despite advances in our understanding of treatment effectiveness, health care costs for LBP are rising,8,9,18–21 with little improvement in health status.9 One explanation for these findings is that patients with chronic LBP receive unnecessary tests and costly treatments that are either ineffective or have limited evidence of effectiveness.9,10,22 Considering the economic costs of chronic LBP (total costs in the United States were estimated at $100–$200 billion in 200523), efforts to improve the quality and appropriateness of care for this condition are needed.

This study extends previous research by using population-based data from North Carolina to examine physical therapy use for chronic LBP. The overall goal of our study was to explore the concepts of underuse, overuse, and misuse of physical therapy for chronic LBP. In its 2001 report, Crossing the Quality Chasm, the Institute of Medicine identified underuse, overuse, and misuse as the 3 main dimensions of poor-quality health care.24 Underuse of care refers to instances in which proven health care practices are not followed. Overuse of care refers to health care resources and procedures being used even when there is no reason to believe they are the best way to help patients. Misuse of care is defined as the failure to properly carry out appropriate treatment plans or the use of inappropriate plans and relates to medical errors.

The specific objectives of our study were: (1) to identify determinants of physical therapy use for chronic LBP, (2) to describe treatments received by individuals who saw a physical therapist for chronic LBP, and (3) to compare use of treatments with current best evidence on care for this condition. Based on previous literature, we hypothesized that both health-related and non–health-related factors would be associated with physical therapy use2,6,25–27 and that not all care delivered by physical therapists would be evidence based.28 In regard to determinants of physical therapy use, we specifically hypothesized that in addition to pain intensity and functional limitations, demographic characteristics, insurance status, and use of physician providers (eg, an orthopedic surgeon) would be associated with physical therapy use.

Method

Data for our study are from a larger, population-based study on the prevalence of chronic back and neck pain and health care use for these conditions.29,30 In the parent study, a cross-sectional, computer-assisted telephone survey of a representative sample of North Carolina households was conducted in 2006 to identify a sample of adults (aged 21 years or older) with chronic low back or neck pain. These individuals then were surveyed on their health and health care use.

Sample Selection

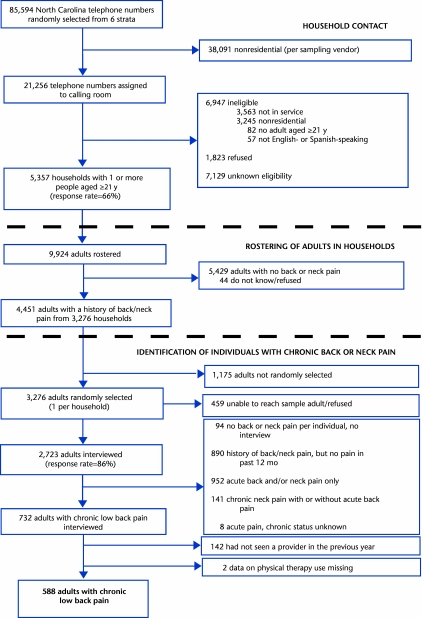

Figure 1 outlines the sampling strategy for the parent study and the current study. A probability sample of North Carolina telephone numbers, stratified by region of the state (western, central, eastern) and concentration of blacks (high [≥15.5%] or low [<15.5%]), was obtained from a sampling vendor.* Blacks were oversampled to ensure adequate representation in the sample and to gain greater precision in parameter estimates on blacks. Telephone contact was made with 5,357 households, and 9,924 adults aged 21 years or older were put on the roster. The household response rate was 66%, computed as the sum of households interviewed divided by the sum of eligible households plus an estimate of the proportion of households with unknown eligibility.31 Of the 9,924 adults on the roster, 4,451 adults from 3,276 households had a history of back or neck pain, defined as any kind of back or neck problem during the past few years. One adult from each of these households was randomly selected to be interviewed in more detail (n=3,276), and 2,723 adults were interviewed, for an individual response rate of 86%. Relative to responders, nonresponders were similar in age and race, but were more likely to be male (chi-square test, P<.001).

Figure 1.

Sample Selection.

Of adults interviewed, 732 had chronic LBP. Low back pain was defined as pain at the level of the waist or below, with or without buttock or leg pain. Chronic pain was defined as pain and activity limitations for the previous 3 months, or more than 24 episodes of activity-limiting pain that had lasted 1 day or more in the previous year. Whereas the former part of this definition is standard, the latter part is based on an earlier study conducted in North Carolina.32 In that study, the investigators found that approximately 10% of the participants had persistent LBP that did not meet the 3-month criterion, but occurred (on average) 2 or more times a month. The sample for this analysis consisted of individuals with chronic LBP who had sought care from 1 or more providers in the previous year and who did not have missing data on use of a physical therapist (n=588).

Survey Procedure

All surveys were conducted by trained personnel at the University of North Carolina's Survey Research Unit. Individuals with chronic LBP answered a series of questions on their symptoms (eg, pain intensity, presence of extremity pain or weakness), general health status (Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey questionnaire [SF-12]), and functional status (Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire).33 They also were asked a number of questions about their health care, including whether they had seen any of the following provider types in the previous year: primary care physician, orthopedic surgeon, neurologic surgeon, doctor of chiropractic, physical medicine and rehabilitation physician, anesthesiologist, neurologist, rheumatologist, psychiatrist, physical therapist, acupuncturist, or other. Respondents who indicated that they had seen 1 or more providers were specifically asked about the number of visits they had made to each provider and the types of diagnostic tests and treatments they had received. Respondents also were asked if they had received any of the following physical interventions: traction, corset or brace, spinal manipulation, electrical stimulation, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation at home, heat, cold, ultrasound, massage, or exercise instruction. The interview ended with questions on insurance, employment, and demographic characteristics. On average, the interview took 35 minutes to complete.

Analytic Framework for Identifying Determinants of Physical Therapy Use

To identify factors that predict physical therapy use, we used Andersen and Newman's socio-behavioral model of health care utilization34,35 and hypothesized that predisposing, enabling, and need characteristics of the individual would influence use. Because physical therapy use often is dependent upon physician referral and because the literature suggests that physician specialty affects referral to physical therapists,1,36 we also included measures of physician use in our model.

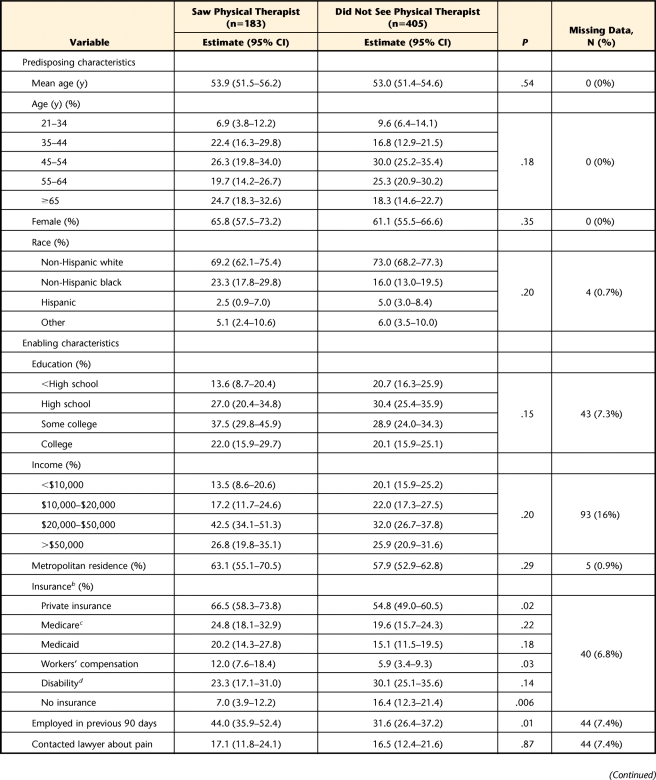

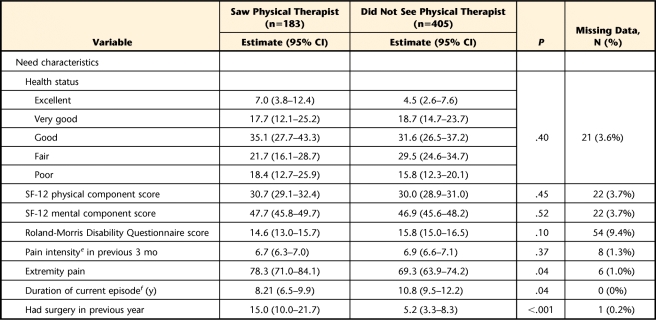

The specific variables included in our analyses were based upon our analytic framework and availability. The dependent variable (ie, physical therapy use) was a dichotomous variable indicating whether the survey respondent had seen a physical therapist in the previous year. Need variables included general health status, SF-12 physical and mental component scores, Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire score, pain intensity (0–10 scale) over the previous 3 months, presence of extremity pain, duration of current back pain episode (years), and whether the individual had had surgery in the previous year. Enabling characteristics included insurance status, education level, income, location (urban or rural) of the patient's residence, employment status over the previous 90 days, and whether the individual had contacted a lawyer regarding his or her back pain. We also examined physician use by determining whether the individual had seen any physician in the previous year and by examining use of specific specialists who would be likely to refer patients to physical therapists (ie, neurologists, neurosurgeons, orthopedic surgeons, physiatrists, primary care physicians, rheumatologists, anesthesiologists, and chiropractors). Anesthesiologists were included because of their presence in pain clinics.37 Chiropractors were included to explore their role as a complementary or alternative provider type. Predisposing characteristics included age, sex, and race. Table 1 presents characteristics of the sample by physical therapy use.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Individuals With Chronic Low Back Pain by Physical Therapy Use (n=588)a

95% CI=95% confidence interval, SF-12=Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short-Forum Health Survey questionnaire.

b Categories not mutually exclusive.

c Only individuals aged ≥62 y.

d Includes individuals aged <62 y who were receiving Medicare.

e 0–10 scale.

f Excludes individuals with >24 episodes of low back pain in previous year (n=55).

Utilization of Treatments by Physical Therapists

To examine use of treatments by physical therapists, we limited our sample to individuals who had seen a physical therapist, but not a chiropractor, in the previous year (n=126). We did this because the survey did not specifically relate treatments received to the provider. In pilot testing of the survey, we found that asking respondents to relate treatments to each of the providers was confusing and time-consuming. We also only focused our analysis on physical treatments likely to be delivered by a physical therapist. We utilized the systematic reviews conducted by the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society,11,38 in addition to active Cochrane Collaboration systematic reviews to represent the current best evidence available for the management of chronic LBP.12–17,39

Data Analysis

Sample weights were created using data provided by the sampling vendor.* The weights were adjusted to account for the differential probability of selection into the sample caused by factors such as the number of household landline telephones and stratum-specific nonresponse. To reduce bias resulting from differences in response rates among demographic subgroups, a post-stratification adjustment was made by calibrating the weighted sample to the distribution of the North Carolina population with respect to age, race, and sex. Data from the 2005 American Community Survey40 (conducted by the US Census Bureau) were used for the calibration.

All analyses were conducted using the survey commands in Stata (version 10.1),† which utilized the sample weights and accounted for the complex sampling design. The analyses, therefore, apply to the population of North Carolina. To identify determinants of physical therapy use, we first conducted bivariate analyses of all of our explanatory variables (ie, predisposing, enabling, need, and provider characteristics) stratified by physical therapy use. Chi-square tests and t tests were used to assess group differences. We then conducted a multivariable logistic regression analysis to examine the combined effects of the explanatory variables on physical therapy use. Because of sample size limitations and collinearity among the explanatory variables, not all variables included in the bivariate analyses were included in the multivariable analysis. Our choice of variables was based on the results of our bivariate analyses, our collinearity assessment, preliminary regression models, completeness of data (eg, income data were missing for many of the participants), findings in previous literature, and clinical experience.

Explanatory variables in the multivariable model included the following demographic characteristics: age, sex, race (white, nonwhite), education (high school education or less, more than high school education), and insurance (Medicare or private, Medicaid, workers' compensation, disability, or none). We considered education level, Medicaid, and no insurance as proxy measures for socioeconomic status. We included indicators for use of the following physician types: primary care, orthopedic surgeon, neurosurgeon, physiatrist, and anesthesiologist. Measures of health or need included the SF-12 physical component score and presence of extremity pain. Whereas preliminary models also included surgery in the previous year, this variable was not significant because of its correlation with having seen an orthopedic surgeon or neurosurgeon in the past year. We first ran main effects models and then explored whether the effect of race was modified by insurance status and whether the effect of insurance status was modified by physician use. All multivariable analyses were limited to records with complete data on all variables.

We conducted descriptive analyses to assess the frequency of use of physical treatments for respondents who saw a physical therapist. We summarized the reviews on the effectiveness of the physical treatment, separately classifying treatment effectiveness as (+) or (−) or as unclear or unable to estimate.29

We conducted 3 sensitivity analyses. We first explored whether our results changed if individuals who had not sought care in the previous year were included in the analyses. We then explored how our results on factors associated with physical therapy use changed if we included income as an alternative measure of socioeconomic status in the multivariable analyses. Because data on income were missing for 16% of the sample, we created a missing indicator variable when conducting these analyses. Finally, we explored how our results on use of treatments changed if patients who saw both a physical therapist and a chiropractor were included.

Role of the Funding Source

This study was funded by National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases grant R01 R051970.

Results

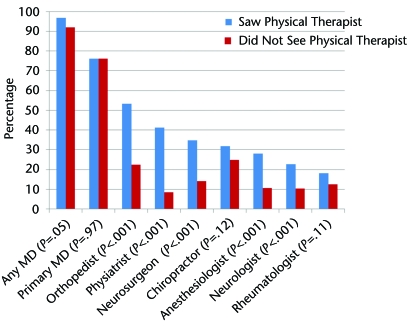

In weighted analyses, 29.7% of the sample reported having seen a physical therapist in the previous year, with a mean of 15.6 visits (95% CI=11.9–19.4) among those who had seen a physical therapist at least once. Few of the predisposing, enabling, or need characteristics were associated with physical therapy use in the bivariate analyses (Tab. 1). Individuals who had private insurance, who were receiving workers' compensation, or who had been employed in the previous 90 days were more likely to have seen a physical therapist. Individuals without insurance were less likely to have seen a physical therapist. The presence of lower-extremity pain and having had surgery in the previous year were positively associated with physical therapy use, whereas duration of the problem was inversely related to physical therapy use. Figure 2 presents results on provider use, stratified by physical therapy use. Patients who saw specialist physicians, with the exception of rheumatologists, were more likely to see a physical therapist.

Figure 2.

Percentage of sample who saw each provider type, stratified by physical therapy use.

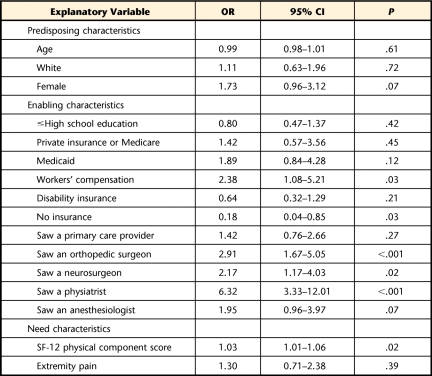

In the multivariable analysis (Tab. 2), receiving workers' compensation and seeing an orthopedic surgeon, neurosurgeon, or physiatrist were positively associated with physical therapy use. Higher SF-12 physical component scores also were associated with physical therapy use. Having no insurance was negatively associated with physical therapy use. Findings on interactions between race and insurance and between provider use and insurance were not significant.

Table 2.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Analysis of Factors Associated With Physical Therapy Use (n=537)a

Analysis limited to records with no missing variables. OR=odds ratio, 95% CI=95% confidence interval, SF-12=Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short-Forum Health Survey questionnaire.

Odds ratios are difficult to interpret in a clinically meaningful way because they deal with “odds” of the event occurring. Although not synonymous with risk ratios, they can be loosely interpreted as such. In Table 2, the significant odds ratio of 1.03 for the SF-12 physical component score can be interpreted as follows: the probability of having seen a physical therapist in the previous year increases by 3% (1.03−1.00) for each 1-point increase in the SF-12 physical component score. The significant odds ratio of 0.18 for having no insurance can be interpreted as follows: individuals with no insurance were 82% less likely (1.00−0.18) to have seen a physical therapist in the previous year than were those with insurance.

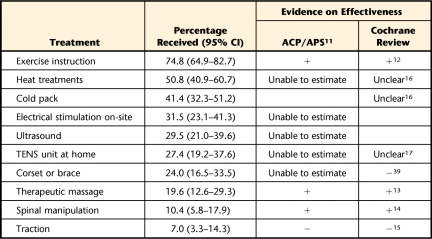

The frequency of use of physical treatments is presented in Table 3. Exercise instruction was the most common treatment received and one of the few with support for effectiveness. Therapeutic massage and spinal manipulation also have support for effectiveness but were received by less than 20% of the sample. Use of heat or cold and electrical stimulation modalities was moderately frequent (27%–50%), although support for the effectiveness of these treatments is unclear. Seven percent of the sample received traction, a treatment that has been shown to be ineffective for chronic LBP, and almost one quarter of the sample received a corset or brace, another ineffective intervention for chronic LBP.

Table 3.

Receipt of Physical Treatments in Previous Year by Individuals Who Saw a Physical Therapist (n=126)a

Excluding participants who saw a chiropractor. 95% CI=95% confidence interval, ACP/APS=American College of Physicians/American Pain Society, TENS=transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.

Sensitivity Analyses

Our bivariate findings on determinants of physical therapy use were similar when including individuals who had not sought care in the previous year (n=142) in the “Did not see a physical therapist” group. The only differences were that individuals who were more educated were significantly more likely to see a physical therapist (out of individuals who had seen a physical therapist in the previous year, 60% had more than a high school education, whereas only 41% of individuals who had not seen a physical therapist had more than a high school education [P=.002]) and individuals who had seen a chiropractor were more likely to have seen a physical therapist (out of individuals who had seen a physical therapist, 32% also had seen a chiropractor, whereas only 19% of individuals who had not seen a physical therapist had seen a chiropractor). Our multivariable analyses also were similar, with only slight changes in the point estimates of the odds ratios but no changes in the significance of the estimates.

When we included income instead of education in the multivariable analyses of physical therapy use, the variable approached statistical significance. Individuals in the lowest household income bracket (<$10,000) were less likely to use physical therapy (OR=0.47, P=.05) relative to individuals in the higher income brackets, and the “no insurance” variable became not significant, indicating that individuals in the lower income bracket also were more likely to be uninsured.

In regard to utilization of treatments, when we included individuals who had seen both a physical therapist and a chiropractor (n=57) in our analyses, the point estimates for the percentage of individuals who received each type of treatment increased slightly, but not significantly, with the exception of those who had received manipulation, which increased to 30.9% (95% CI=23.9–38.9).

Discussion

Approximately 30% of the sample who had sought care in the previous year had seen a physical therapist, with a mean of 16 visits. Carey et al32 reported similar findings from a 1992 population-based sample of North Carolinians with chronic LBP. They found that 29.1% of their sample had sought care from a physical therapist, with a mean of 17.2 visits. These findings suggest little change from 1992 to 2006 in physical therapy use for the management of chronic LBP in North Carolina, although physical therapy use may have fluctuated during the intervening years. Although not specific to chronic LBP, data from MEPS also indicate little change, from 1997 to 2005, in the proportion of individuals with back and neck pain who sought care from a physical therapist.9,10

The fact that fewer than one third of this highly disabled (mean SF-12 physical component score=30), care-seeking sample received physical therapy suggests potential underuse and missed opportunities for therapists to deliver and patients to receive effective treatments. Although we were not able to determine whether patients had seen a physical therapist prior to the previous year, our bivariate analysis (Tab. 1) indicated that individuals with a longer duration of chronic LBP were less likely to have seen a physical therapist in the previous year. We did not include this variable in our multivariable analyses, as it was not applicable to individuals in our sample who had had more than 24 episodes of LBP in the previous year.

Our multivariable analysis of determinants of physical therapy use sheds some light on potential facilitators of and barriers to receiving physical therapy. In the multivariable analysis, enabling characteristics and the use of specialist physicians in particular were the strongest predictors of physical therapy use. The relationship between physician use and physical therapy use is not surprising, considering that many insurance plans require a physician referral for physical therapy. Previous literature also suggests that specialist physicians are more likely to refer to physical therapists than are primary care physicians.36 One possible explanation for this finding is that specialist physicians have firmer ties with physical therapists, because a conservative approach often is the specialist's first step before more-invasive treatments such as surgery. In addition, physical therapy often is prescribed by the physician after surgery. In bivariate analyses, having had surgery in the previous year was associated with physical therapy use. We excluded this variable from the multivariable analyses, as it was highly correlated with visits to an orthopedic surgeon or neurosurgeon. Our findings on specialist physician use suggest that opportunities may exist for physical therapists to establish stronger working relationships with the primary care community, a concept or approach (ie, multidisciplinary, coordinated care across settings) that currently is being promoted as a way to improve quality of care.

Insurance, another enabling factor, also played a role in physical therapy use. Individuals who received workers' compensation were more likely to see a physical therapist, and those without insurance were less likely to see a physical therapist. Several studies have shown a positive association between workers' compensation and use of physical therapists.6,26,27,36 With the potential changes coming as a result of health care reform, access to physical therapy for uninsured individuals may improve.

We found no evidence of racial disparities in physical therapy use for chronic LBP. Data on racial disparities in physical therapy use are limited. Carter and Rizzo,25 in their analysis of MEPS data, reported that blacks and Hispanics were less likely to receive physical therapy for the management of musculoskeletal conditions. Their method of controlling for need characteristics (ie, illness severity and functional limitations), however, was limited. In 2 other population-based studies on physical therapy use, racial disparities were not present,36,41 nor were they present in an analysis of data from the National Spine Network.6

We also did not find any other demographic or urban versus rural disparities in physical therapy use, in contrast to the study by Lim et al,7 who found that younger individuals and women with chronic LBP were more likely to see a physical therapist. Other reports in the literature also indicate that men and older individuals are less likely to use physical therapy for the management of musculoskeletal conditions.6,25,36 Literature on urban versus rural disparities in physical therapy use are limited and has reported conflicting results.25,41 One explanation for the differences in findings between this study and others is sample differences. Our sample was limited to individuals with chronic LBP, a group that is highly engaged with the health care system,29 who had sought care in the past year. Because findings from our sensitivity analysis, which included people who had not sought care in the previous year, were similar to our primary findings, care-seeking differences do not appear to play a part in the differences between studies.

Contrary to what we had expected, SF-12 physical component scores were positively associated with physical therapy use, indicating that individuals who saw a physical therapist had higher levels of function. Because of the cross-sectional design of the survey, we are unable to determine whether use of physical therapy improved function, or whether individuals with higher levels of function sought physical therapy. If the latter is true, this would suggest potential underuse of physical therapy and missed opportunities. Individuals with greater functional limitations have more to gain from rehabilitation and often make greater gains relative to those with fewer limitations. Future studies on physical therapy use for chronic LBP should explore this issue.

The patterns of use of physical therapy treatments for chronic LBP were fairly encouraging, considering that it can take up to 2 decades for the diffusion and adoption of evidence into clinical practice.42,43 Almost three quarters of the sample who had seen a physical therapist received exercise instruction, an effective intervention for chronic LBP,12,44 and fewer than 10% received traction, an ineffective treatment for chronic LBP.15 Based on current evidence, therapeutic massage13 and spinal manipulation14 were underutilized, and corsets and braces39 were overutilized.

Use of physical treatments lacking strong evidence for effectiveness or ineffectiveness are more difficult to classify using the Institute of Medicine taxonomy. It could be argued that excessive use of treatments lacking evidence of effectiveness is an example of overuse. Although not specifically addressed in this study, misuse or errors in the delivery of physical therapy interventions for chronic LBP are not as likely as in some other areas of care (eg, surgery). A feasible example of misuse of physical therapy for this population would be burning a patient when applying a heat treatment.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, it was conducted in one state (ie, North Carolina), which may limit the generalizability of the findings. North Carolina, however, has diverse demographic, socioeconomic, and geographic (ie, urban/rural) characteristics. A second limitation is that we relied on patient self-report. Although we conducted a pilot study to verify that individuals were accurate in their recall of past providers and number of visits,29 we did not specifically examine the use of physical treatments. We also were unable to determine with certainty that the physical treatments received were delivered by a physical therapist. Although our sample was limited to individuals who had seen a physical therapist and not a chiropractor, some treatments (eg, brace or corset) may have been delivered by a physician. We explored the relationship between receipt of specific treatments and being seen by specific types of physicians. These findings were unremarkable, although quite limited by small sample sizes. Limitations notwithstanding, this research adds to the limited current research on physical therapy use for chronic LBP.

Conclusions

Fewer than one third of individuals with chronic LBP who had sought care in the previous year saw a physical therapist. Both health-related and non–health-related factors were associated with physical therapy use for chronic LBP, with insurance status and use of physician specialists as the strongest predictors. Individuals who saw a physical therapist did not always receive treatments that were evidence-based. Our findings provide insight into potential opportunities for improving access to and quality of physical therapy for chronic LBP.

Footnotes

Dr Freburger and Dr Carey provided concept/idea/research design, data collection, and fund procurement. Dr Freburger and Dr Holmes provided writing. Dr Freburger provided institutional liaisons. All authors provided data analysis and consultation (including review of the manuscript before submission).

This study was funded by National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases grant R01 R051970.

GENESYS Sampling System, 565 Virginia Dr, Fort Washington, PA 19034-2706.

StataCorp LP, 4905 Lakeway Dr, College Station, TX 77845.

References

- 1. Freburger JK, Carey TS, Holmes GM. Physician referrals to physical therapists for the treatment of spine disorders. Spine J. 2005;5:530–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jette AM, Davis KD. A comparison of hospital-based and private outpatient physical therapy practices. Phys Ther. 1991;71:366–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bekkering GE, Hendriks HJM, Koes BW, et al. Dutch physiotherapy guidelines for low back pain. Physiotherapy. 2003;89:82–96 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Ostelo R, et al. Clinical guidelines for the management of low back pain in primary care: an international comparison. Spine. 2001;26:2504–2513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Tulder MW, Becker A, Bekkering T, et al. European guidelines for the management of acute nonspecific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(suppl):S169–S191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Freburger JK, Carey TS, Holmes GM. Management of back and neck pain: who seeks care from physical therapists? Phys Ther. 2005;85:872–886 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lim KL, Jacobs P, Klarenbach S. A population-based analysis of healthcare utilization of persons with back disorders: results from the Canadian Community Health Survey 2000–2001. Spine. 2006;31:212–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Feuerstein M, Marcus SC, Huang GD. National trends in nonoperative care for nonspecific back pain. Spine J. 2004;4:56–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Martin BI, Deyo RA, Mirza SK, et al. Expenditures and health status among adults with back and neck problems. JAMA. 2008;299:656–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Martin BI, Turner JA, Mirza SK, et al. Trends in health care expenditures, utilization, and health status among US adults with spine problems, 1997–2006. Spine. 2009;34:2077–2084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chou R, Huffman LH. Nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:492–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Malmivaara A, Koes BW. Exercise therapy for treatment of non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3:CD000335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Furlan AD, Imamura M, Dryden T, Irvin E. Massage for low back pain: an updated systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine. 2009;34:1669–1684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Assendelft WJ, Morton SC, Yu EI, et al. Spinal manipulative therapy for low back pain. A meta-analysis of effectiveness relative to other therapies. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:871–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Clarke J, van Tulder M, Blomberg S, et al. Traction for low back pain with or without sciatica: an updated systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane collaboration. Spine. 2006;31:1591–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. French SD, Cameron M, Walker BF, et al. A Cochrane review of superficial heat or cold for low back pain. Spine. 2006;31:998–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Khadilkar A, Milne S, Brosseau L, et al. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for the treatment of chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Spine. 2005;30:2657–2666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carrino JA, Morrison WB, Parker L, et al. Spinal injection procedures: volume, provider distribution, and reimbursement in the U.S. Medicare population from 1993 to 1999. Radiology. 2002;225:723–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Deyo RA, Gray DT, Kreuter W, et al. United States trends in lumbar fusion surgery for degenerative conditions. Spine. 2005;30:1441–1445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Friedly J, Chan L, Deyo R. Increases in lumbosacral injections in the Medicare population: 1994 to 2001. Spine. 2007;32:1754–1760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Luo X, Pietrobon R, Hey L. Patterns and trends in opioid use among individuals with back pain in the United States. Spine. 2004;29:884–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Deyo RA, Nachemson A, Mirza SK. Spinal-fusion surgery: the case for restraint. N Engl J Med. 2004;35:722–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Katz JN. Lumbar disc disorders and low-back pain: socioeconomic factors and consequences. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(suppl 2):21–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Berwick DM. A user's manual for the IOM's “Quality Chasm” report. Health Aff. 2002;21:80–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Carter SK, Rizzo JA. Use of outpatient physical therapy services by people with musculoskeletal conditions. Phys Ther. 2007;87:497–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jette AM, Smith K, Haley SM, Davis KD. Physical therapy episodes of care for patients with low back pain. Phys Ther. 1994;74:101–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mielenz TJ, Carey TS, Dyrek DA, et al. Physical therapy utilization by patients with acute low back pain. Phys Ther. 1997;77:1040–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fritz JM, Cleland JA, Brennan GP. Does adherence to the guideline recommendation for active treatments improve the quality of care for patients with acute low back pain delivered by physical therapists? Med Care. 2007;45:973–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Carey TS, Freburger JK, Holmes GM, et al. A long way to go: practice patterns and evidence in chronic low back pain care. Spine. 2009;34:718–724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Freburger JK, Holmes GM, Agans RP, et al. The rising prevalence of chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:251–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 4th ed Lenexa, KS: American Association for Public Opinion Research; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Carey TS, Evans A, Hadler N, et al. Care-seeking among individuals with chronic low back pain. Spine. 1995;20:312–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Roland M, Fairbank J. The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire. Spine. 2000;25:3115–3124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Millbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1973;51:95–124 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Freburger JK, Holmes GM, Carey TS. Physician referrals to physical therapy for the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:1839–1849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Castel LD, Freburger JK, Holmes GM, et al. Spine and pain clinics serving North Carolina patients with back and neck pain: what do they do, and are they multidisciplinary? Spine. 2009;34:615–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chou R, Atlas SJ, Stanos SP, Rosenquist RW. Nonsurgical interventional therapies for low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society clinical practice guideline. Spine. 2009;34:1078–1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. van Duijvenbode IC, Jellema P, van Poppel MN, van Tulder MW. Lumbar supports for prevention and treatment of low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2:CD001823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. US Census Bureau Quick Guide to the 2005 American Community Survey Products in American FactFinder. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov/home/saff/aff_acs2005_quickguide.pdf Accessed January 17, 2011

- 41. Freburger JK, Holmes GM. Physical therapy use by community-based older people. Phys Ther. 2005;85:19–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Translating research into practice (TRIP)-II: fact sheet. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/research/trip2fac.htm Accessed August 11, 2010

- 43. Berwick DM. Disseminating innovations in health care. JAMA. 2003;289:1969–1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Tomlinson G. Systematic review: strategies for using exercise therapy to improve outcomes in chronic low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:776–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]