Abstract

Misshapen/NIKs (Nck-interacting kinases)-related kinase (MINK) and closely related TRAF2/Nck-interacting kinase (TNIK) are proteins that specifically bind to activated Rap2 and are thus hypothesized to relay its downstream signal transduction. Activated Rap2 has been found to stimulate dendritic pruning, reduce synaptic density and cause removal of synaptic AMPA receptors (AMPA-Rs) (Zhu et al., 2005; Fu et al., 2007). Here we report that MINK and TNIK are postsynaptically enriched proteins whose clustering within dendrites is bidirectionally regulated by the activation state of Rap2. Expression of MINK and TNIK in neurons is required for normal dendritic arborization and surface expression of AMPA receptors. Overexpression of a truncated MINK mutant unable to interact with Rap2 leads to reduced dendritic branching and this MINK-mediated effect on neuronal morphology is dependent upon Rap2 activation. While similarly truncated TNIK also reduces neuronal complexity, its effect does not require Rap2 activity. Furthermore, Rap2-mediated removal of surface AMPA-Rs from spines is entirely abrogated by coexpression of MINK, but not TNIK. Thus, although both MINK and TNIK bind GTP-bound Rap2, these kinases employ distinct mechanisms to modulate Rap2-mediated signaling. MINK appears to antagonize Rap2 signal transduction by binding to activated Rap2. We suggest that MINK interaction with Rap2 plays a critical role in maintaining the morphological integrity of dendrites and synaptic transmission.

Introduction

Ras GTPases, including Ras, Rap1 and Rap2, instigate signaling pathways controlling synaptic structure and function. In neurons, Rap proteins appear to play largely opposing roles to Ras signal transduction. For instance, overexpression of constitutively active Ras stimulates dendritic spine outgrowth, whereas constitutively active Rap2 induces spine loss and dendrite shortening (Fu et al., 2007). The strength of synapses is modifiable and may be increased via long-term potentiation (LTP) or decreased via long-term depression (LTD). These synaptic modifications involve regulated trafficking of AMPA-Rs (Bliss and Collingridge, 1993; Bear and Malenka, 1994; Malinow and Malenka, 2002; Bredt and Nicoll, 2003; Collingridge et al., 2004; Miyamoto, 2006; Shepherd and Huganir, 2007; Hanley, 2008). Ras, Rap1 and Rap2 are essential regulators of AMPA-R trafficking; Ras activation has been associated with LTP, whereas Rap1 and Rap2 have been implicated in LTD and depotentiation, respectively (J. J. Zhu et al., 2002, Y. Zhu et al., 2005; for review, see Stornetta and Zhu, 2010). These studies suggest Ras function may be related to growth and strengthening of synapses, while Rap1 and Rap2 activation are implicated in elimination and weakening of synapses.

Misshapen/NIKs (Nck-interacting kinases)-related kinase (MINK) and TRAF2/Nck-interacting kinase (TNIK) are members of the germinal center kinase (GCK) IV family of proteins (Fu et al., 1999; Dan et al., 2000). GCK proteins are characterized by an N-terminal kinase domain and a C-terminal citron homology (CNH) domain separated by a variable region of lower sequence homology (Dan et al., 2001). MINK and TNIK specifically bind to Rap2 via their CNH domains (Taira et al., 2004; Nonaka et al., 2008). Since they only bind GTP-bound Rap2 MINK and TNIK are presumed to be downstream targets or effectors of Rap2 (Taira et al., 2004; Nonaka et al., 2008; Kawabe et al., 2010).

Proteomic analyses suggest that MINK and TNIK may be components of the postsynaptic density (PSD) (Jordan et al., 2004; Peng et al., 2004; Collins et al., 2006; Trinidad et al., 2008). Here we demonstrate that MINK and TNIK are highly enriched in the PSD. Loss of neuronal MINK or TNIK expression leads to removal of surface AMPA-Rs and simplification of neuronal arbors. Notably, both of these phenotypes result from Rap2 activation (Zhu et al., 2005; Fu et al., 2007). We have determined that a truncated MINK unable to interact with Rap2 causes atrophy of dendritic arbors in a manner that requires activation of Rap2. Furthermore, MINK, but not TNIK overexpression, is sufficient to disrupt Rap2-mediated removal of AMPA-Rs, suggesting that MINK and TNIK differentially impinge upon Rap2 signaling. Although MINK is proposed to act as an effector that simply transduces activated Rap2 signaling (Taira et al., 2004; Nonaka et al., 2008), our data indicate that MINK functions as a negative regulator of Rap2-mediated signal transduction to control neuronal structure and AMPA-R trafficking.

Materials and Methods

DNA constructs.

Full-length pCDNA3 Flag- and HA-tagged wild-type MINK, TNIK, NIK, and MINK kinase dead mutants (K54R) were gifts from Ippeita Dan (Kusumi Membrane Organizer Project, Nagoya, Japan). pGW1-HA-Rap2V12 (HA-Rap2(ca)) or pGW1-HA-Rap2N17 (HA-Rap2(dn) were gifts from D. Pak (Georgetown University, Washington, DC). Firefly Luciferase RNAi was generated as described previously (Seeburg and Sheng, 2008). The following oligonucleotides were annealed and cloned into the HindIII and BglII sties of pSuper vector to make constructs for TNIK RNAi: 5′-GATCCCCCATCTGCAGGGAAATCTTATTCAAGAGATAAGATTTCCCTGCAGATGTTTTTGGAAA-3′ and 5′-AGCTTTTCCAAAAACATCTGCAGGGAAATCTTATCTCTTGAATAAGATTTCCCTGCAGATGGGG-3′; MINK RNAi: 5′-GATCCCCGTACTCTCACCATCGCAATTTCAAGAGAATTGCGATGGTGAGAGTACTTTTTGGAAA-3′ and 5′-AGCTTTTCCAAAAAGTACTCTCACCATCGCAATTCTCTTGAAATTGCGATGGTGAGAGTACGGG-3′. MINK RNAi sequences previously validated by (McCarty et al., 2005) were adapted for insertion into pSuper.

Tissue distribution, PSD fractionation, and biochemistry.

Postnuclear supernatants from different tissues and brain regions were prepared and processed for Western blotting as described previously (Hussain et al., 1999). For PSD fractionation whole brains were homogenized in buffer 1 (0.32 m sucrose, 4 mm HEPES, pH 7.4) and spun at 1400 × g for 10 min. The pellet (P1) was set aside and the supernatant (S1) was spun at 13,800 × g for 15 min. The supernatant (S2) was set aside while the crude synaptosomal pellet (P2) was resuspended in buffer 1, and spun again. The resultant pellet (P2′) was washed with buffer 1 and then lysed hypotonically with ice-cold water. The pH was quickly brought to 7.4 by addition of concentrated HEPES, pH 7.4. The lysed P2′ was centrifuged for 20 min at 25 000 × g, giving rise to pellet LP1. This pellet was resuspended in 0.5% Triton X-100 and spun 20 min at 32 000 × g giving rise to the pellet PSD fraction which was resuspended in buffer 1. Hippocampal cultures grown for 13 or 20 d in vitro (DIV) were homogenized (H) in 20 mm Tris HCl, pH 7.4; 150 mm NaCl, followed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 10 min to generate supernatant (S) and pellet (P) fractions. Pellet fractions were resuspended in homogenization buffer.

Neuronal culture and immunostaining.

Commercial antibodies used in this study include those against Rap1, Rap2, and HA (Covance), tubulin and Flag (Sigma-Aldrich), MINK, TNIK, and MINK/TNIK (GeneTex), Bassoon (Stressgen), GluR1 (Calbiochem), Alexa-conjugated phalloidin and secondary antibodies (Invitrogen).

Hippocampal neurons were dissected from embryonic day 19 (E19) Sprague Dawley rat embryos, plated onto coated glass coverslips (30 μg/ml PDL and 2.5 μg/ml laminin), and cultured in Neurobasal medium (Invitrogen) with B27 (Invitrogen), 0.5 mm glutamine, and 12.5 μm glutamate.

Neurons were transfected after 18 DIV and processed following 3–4 d of overexpression. Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For RNAi experiments, each well of neurons was cotransfected with 1 μg of pGW1-DsRed2 or pGW1-Venus and 2.5 μg of pSuper or RNAi constructs. Neurons were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and 4% sucrose for 8 min. The cells were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C in 1× GDB buffer (30 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 0.2% gelatin, 0.5% Triton X-100, and 0.8 m NaCl), followed by secondary antibodies for 2–4 h. For AMPAR staining neurons were fixed for 6 min and incubated with GluR1 antibody overnight in 1× GDB buffer lacking Triton X-100. All subsequent primary and secondary antibody incubations were done in regular 1× GDB buffer as described above.

Electrophysiology.

Organotypic slice cultures were prepared from postnatal day 7 rat hippocampus as described previously (Seeburg and Sheng, 2008). Rat brains were dissected in ice-cold buffer containing (in mm): sucrose (238), KCl (2.5), NaHCO3 (26), NaH2PO4 (1), glucose (11), MgCl2 (5), and CaCl2 (1). Hippocampi were cut into 350-μm-thick slices with a McIlwain tissue chopper, and plated on tissue inserts (Millipore) in wells with MEM (Cellgro) culture medium containing (in mm): glucose (26), NaHCO3 (5.8), HEPES (30), CaCl2 (2), MgSO4 (2), and supplemented with horse serum (20%), insulin (1 μg/μl), and ascorbic acid (0.0012%). Slices were incubated in 5% CO2 at 35°C.

Electrophysiological recordings were performed as described previously (Seeburg and Sheng, 2008). Neurons were transfected by biolistic gene gun at DIV 3–5 (total 100 μg of DNA; 90% test DNA construct; 10% eGFP marker) and recorded 3–4 d after transfection. Recordings were performed in solution containing (in mm): NaCl (119), KCl (2.5), CaCl2 (4), MgCl2 (4), NaHCO3 (26), NaH2PO4 (1), glucose (11), picrotoxin (0.1), and 2-chloroadenosine (0.002–0.004), and bubbled continuously with 5% CO2/95% O2. Patch recording pipettes (2.5–5 MΩ) were filled with internal solution containing (in mm): cesium methanesulfonate (115), CsCl (20), HEPES (10), MgCl2 (2.5), ATP disodium salt (4), GTP trisodium salt (0.4), sodium phosphocreatine (10), and EGTA (0.6), at pH 7.25. Simultaneous whole-cell recordings were obtained from a pair of transfected and neighboring untransfected CA1 pyramidal neurons during stimulation of presynaptic Schaffer collaterals. For basal synaptic transmission experiments, presynaptic fibers were stimulated at 0.2 Hz, and AMPAR EPSCs were recorded at −70 mV. Each data point represents an average of 60 consecutive synaptic responses. All recordings were made using a Multiclamp 700A amplifier (Molecular Devices), and data were digitized at 20 kHz with Digidata 1322A (Molecular Devices). Analysis of recordings was performed using Clampfit software (Molecular Devices). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM, and statistical significance was assessed by ANOVA.

Microscopy and quantification.

Fixed neurons were imaged with an LSM510 confocal microscope system (Zeiss). Confocal z-series image stacks encompassing entire dendrite segments were compressed into a single plane and analyzed using MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging). For all morphometric analyses 5 dendritic segments of 50 μm were collected from at least six neurons. Quantification of protrusion number per unit length of dendrite was obtained from DsRed channel images. For each construct, individual spine measurements were first grouped and averaged per neuron; means from several neurons were then averaged to obtain a population mean (presented as mean ± SEM). For integrated intensity quantification (i.e., average cluster intensity per unit area) different immunostained channels were parsed into separate images. Dendritic segments were outlined and a threshold level for each channel was manually set to exclude diffuse background staining, leaving only the puncta visible; the same threshold level was used for each neuron within an experiment. Statistical significance between samples was calculated using ANOVA.

Results

MINK and TNIK are neuronal proteins enriched in PSDs

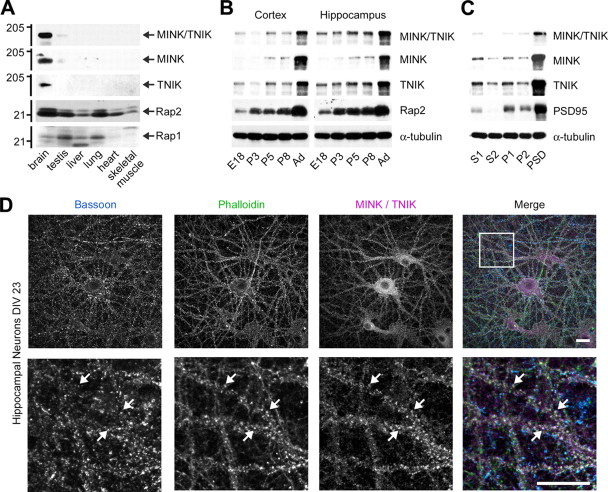

To characterize MINK and TNIK proteins we first analyzed their tissue distribution. Western blot analysis with antibodies detecting both MINK and TNIK or specific to either protein (supplemental Fig. S1A, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) revealed that they are predominately expressed in brain (Fig. 1A). Since both MINK and TNIK have been shown to interact with Rap2, but not Rap1 (Taira et al., 2004; Nonaka et al., 2008), we also characterized the tissue distribution of Rap1 and Rap2. While both proteins are broadly expressed across tissues, expression of Rap2 is highest in brain, whereas Rap1 has relatively weak brain expression relative to some other tissues (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Tissue and developmental distribution of MINK/TNIK proteins. A, Western blot analysis of postnuclear supernatants isolated from adult rat tissues. Molecular mass is indicated in kilodaltons. B, Developmental regulation of MINK and TNIK. Postnuclear supernatant Western blot analyses of hippocampus and cortex isolated from embryonic, postnatal and adult rat tissues. E18, Embryonic day 18; P3, P5, P8, postnatal day 3, 5, and 8, respectively; Ad, adult. C, MINK and TNIK are enriched in PSD. Western blot analyses of PSD subcellular fractionation from rat brain. S1, P1, Whole-brain postnuclear supernatant and membrane fractions, respectively; S2, cytosolic proteins; P2, crude synaptosomal fraction (20 μg each); PSD, Triton X-100-extracted PSD (5 μg of protein). Antibodies for immunoblotting are indicated to the right of panels. D, Subcellular distribution of MINK/TNIK in hippocampal neurons. Confocal microscopy of 23-d-old hippocampal neurons stained for MINK/TNIK, phalloidin, and bassoon. Arrows indicate colocalized puncta. Box in “merge” panel indicates region of higher magnification. Scale bars, 20 μm.

Studies at the mRNA level show that MINK expression rises during postnatal brain development (Dan et al., 2000). We asked whether protein expression of MINK and TNIK is similarly upregulated in specific neuronal subregions. Western blot analyses demonstrate that MINK and TNIK show increased expression from E18 to adulthood in rat cortex and hippocampus (Fig. 1B). In addition, MINK expression was developmentally regulated in cultured hippocampal neuron extracts (supplemental Fig. S1B, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). We observed a similar developmental increase in the expression of Rap2 (Fig. 1B; supplemental Fig. S1B, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Thus, the protein distribution (Fig. 1A) and developmental regulation (Fig. 1B) of MINK, TNIK and Rap2 are consistent with their functional interaction in brain.

Proteomic studies of PSD fractions identified peptide sequences corresponding to MINK and TNIK, suggesting that these proteins may exist within the PSD (Jordan et al., 2004; Peng et al., 2004; Collins et al., 2006). To validate these data we analyzed the distribution of MINK and TNIK in a subcellular fractionation of brain extract leading to purified PSDs. We resolved that MINK and TNIK proteins are not only expressed within synapses, they are specifically enriched components of the PSD, similar to PSD-95 (Fig. 1C).

We used an antibody that reacts to both proteins to characterize MINK and TNIK expression in cultured hippocampal neurons (supplemental Fig. S1A, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material and 1D), as the antibodies that specifically recognize either MINK or TNIK were ineffective for immunocytochemistry. Confocal microscopy revealed a punctate dendritic pattern of MINK/TNIK as well as a diffuse distribution throughout the cell body, dendrites and in axons (Fig. 1D). Costaining with phalloidin and the presynaptic marker Bassoon showed partial colocalization of MINK/TNIK within putative dendritic spines (Fig. 1D), consistent with our fractionation data (Fig. 1C). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that MINK and TNIK are neuronal proteins that are concentrated at the synapse.

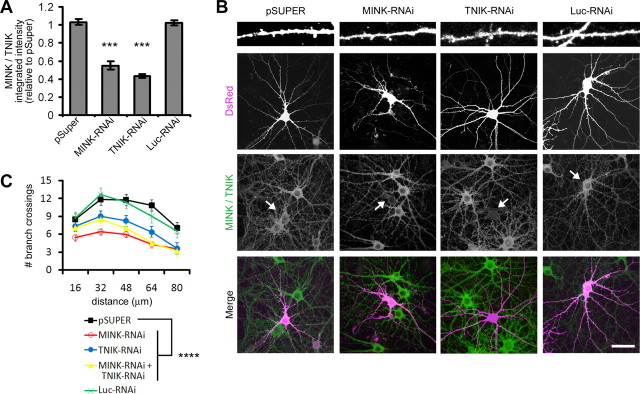

Loss of MINK or TNIK reduces dendritic arborization

To investigate protein function we knocked down expression of MINK and TNIK using plasmid-based RNA interference (RNAi). RNAi constructs targeting MINK (MINK-RNAi) and TNIK (TNIK-RNAi) specifically reduced MINK and TNIK expression, respectively, when transfected in HEK cells (supplemental Fig. S2A, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Neither the MINK-RNAi nor TNIK-RNAi constructs affected expression of the closely related protein Nck interacting kinase (NIK) or the unrelated protein WASP (supplemental Fig. S2A, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Furthermore, MINK-RNAi did not reduce expression of a truncated version of MINK encoding the isolated variable domain (VAR-MINK, which lacks the RNAi target site) (supplemental Fig. S2A, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). To confirm the efficacy of our RNAi constructs in neurons, we transfected hippocampal cultures with DsRed and either empty pSuper vector or RNAi constructs targeting MINK, TNIK, or luciferase (Luc-RNAi) as negative control. Immunostaining with an antibody recognizing MINK/TNIK revealed that RNAi constructs targeting MINK or TNIK caused a significant reduction in endogenous MINK/TNIK expression (Fig. 2A,B).

Figure 2.

MINK- and TNIK-RNAi diminish neuronal complexity. A, Mean cell body MINK/TNIK immunostaining intensity for hippocampal neurons transfected with pSuper or pSuper-based RNAi constructs targeting MINK (MINK-RNAi), TNIK (TNIK-RNAi), or luciferase (Luc-RNAi), as indicated. Mean integrated intensity values were normalized to pSuper-transfected neurons. Error bars indicate ±SEM. ***p < 0.001 relative to pSuper control, ANOVA. n ≥ 12 neurons for each. B, Representative images of hippocampal neurons cotransfected with pSuper or RNAi constructs as indicated, along with DsRed to visualize transfected cell morphology. Immunostaining was performed with antibodies to endogenously expressed MINK/TNIK. Arrows indicate transfected neurons. Dendritic segments at top are 40 μm long. Scale bar, 50 μm. C, Sholl analysis, transfections as indicated (n ≥ 12 neurons for each). A significant difference between transfected groups was confirmed by a 5 × 5 mixed-effect ANOVA, with transfected group as the five-level between-group effect and distance from the soma as the five-level within-group effect (F(4,332) = 15.625; p < 0.0001). Post hoc tests (PLSD) revealed that, relative to pSuper control, a loss of either MINK, TNIK, or simultaneous knockdown of MINK and TNIK significantly reduced dendritic complexity (****p < 0.0001).

The effects of MINK and TNIK knockdown on neuronal morphology were visualized by cotransfected DsRed (Fig. 2B). Neurons were transfected after 18 DIV and processed following 3–4 d of overexpression. Dendritic complexity of transfected neurons was quantified using Sholl analysis which measures the number of dendrites crossing concentric circles at various radial distances from the cell soma. In normal 18-d-old cultured hippocampal neurons, the number of dendritic crossings typically increases distally from the soma until ∼35–45 μm where it then tapers off (Sholl, 1953). Both MINK-RNAi and TNIK-RNAi significantly reduced arbor complexity relative to control neurons (Fig. 2C). No additive or synergistic effect was observed upon simultaneous reduction of MINK and TNIK expression (Fig. 2C).

Collectively, these data demonstrate that a loss of MINK or TNIK function can reduce neuronal complexity and indicates that expression of these proteins is required to maintain structural integrity of neurons.

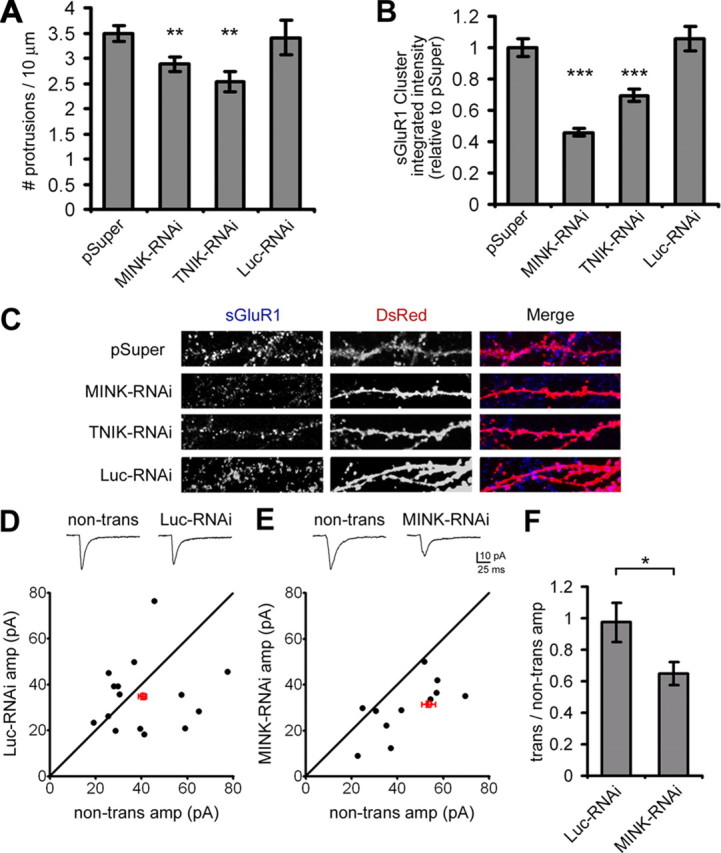

MINK and TNIK knockdown modulate spine density and surface expression of AMPA receptors

Given their robust effects on neuronal arborization, we asked whether loss of MINK or TNIK expression also affects cytoarchitecture at the level of the synapse. We determined that knockdown of either MINK or TNIK caused a significant reduction in the density of dendritic spines (Fig. 3A). To investigate the functional significance of this spine loss, we analyzed the impact of MINK-RNAi and TNIK-RNAi on surface AMPA-R expression in hippocampal dendrites. Quantification of the integrated intensity of surface GluR1 (sGluR1) dendritic clusters revealed a specific decrease after downregulation of either MINK or TNIK expression (Fig. 3B,C). Loss of MINK or TNIK expression caused a similar reduction in sGluR2 dendritic clustering (supplemental Fig. S2B, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Further, we examined the effect of reduced MINK on excitatory synaptic transmission in CA1 pyramidal neurons. Hippocampal slice cultures DIV 3–5 were transfected with GFP and either MINK-RNAi or Luc-RNAi as a control. Three to 4 d after transfection simultaneous recording of AMPA-EPSCs was performed from neighboring nontransfected CA1 neurons and transfected CA1 pyramidal neurons that were identified by GFP fluorescence. While Luc-RNAi did not significantly alter the amplitude of AMPA-EPSCs (Fig. 3D), MINK-RNAi yielded a significant depression in amplitude relative to nontransfected neighboring neurons (Fig. 3E). While the average AMPA-EPSC ratio of transfected versus nontransfected neighboring neurons differed significantly between MINK-RNAi and Luc-RNAi (Fig. 3F), the average NMDA-EPSC ratio did not (data not shown). These data demonstrate that in addition to playing a critical role in neuronal structure, expression of MINK and TNIK in neurons seems necessary for surface AMPA-R expression and function.

Figure 3.

Loss of MINK or TNIK reduces synapse number and AMPA-R function. A, Mean density of dendritic protrusions analyzed per 10 μm of dendritic length in neurons transfected with pSuper or RNAi constructs as indicated, along with DsRed to visualize transfected cell morphology. Error bars indicate ±SEM. **p < 0.01 relative to pSuper control, ANOVA. n ≥ 12 neurons for each. B, Hippocampal neurons transfected with various constructs, along with DsRed to visualize transfected cell morphology were immunostained for sGluR1 expression. Quantification of mean integrated sGluR1 cluster intensity in dendritic segments normalized to pSuper. Error bars indicate ±SEM. ***p < 0.001 relative to pSuper control, ANOVA. n ≥ 12 neurons for each. C, Representative images of MINK- and TNIK-RNAi effect on GluR1 surface expression in dendritic segments (40 μm). D, E, Effects of MINK downregulation on excitatory synaptic transmission in organotypic hippocampal slice culture. Top, Sample-evoked AMPA-EPSC traces are shown from pairs of nontransfected and neighboring transfected CA1 hippocampal pyramidal cells. Bottom, Pairwise analysis between transfected cells and neighboring nontransfected cells shows that Luc-RNAi has no significant effect on AMPAR-EPSC amplitude (D) (p > 0.3, ANOVA; 15 pairs), while MINK-RNAi causes a significant reduction (E) (**p < 0.01, ANOVA; 13 pairs). Filled circles represent a single pair of recordings; open red circle and error bars represent mean ±SEM. F, Summary of Luc-RNAi and MINK-RNAi expression effects on AMPA-R-EPSCs. Each bar graph represents average of ratios obtained from multiple pairs of transfected and nontransfected neighboring neurons. Error bars indicate mean ±SEM. *p < 0.05 for MINK-RNAi relative to Luc-RNAi control, ANOVA.

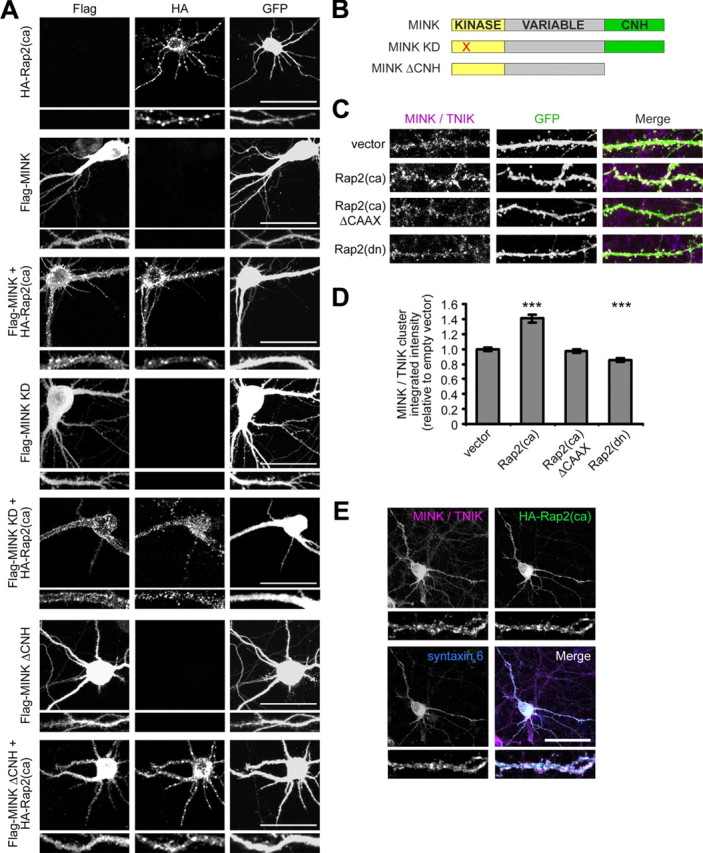

MINK and TNIK localization in neurons is modulated by the activation state of Rap2

Having established the importance of MINK and TNIK in maintaining synaptic structure and function, we next sought to investigate the mechanism of these actions. Notably, overexpression of activated Rap2 is reported to produce each of the phenotypes we characterized for a loss of MINK and TNIK expression (Zhu et al., 2005; Fu et al., 2007). Furthermore, both MINK and TNIK directly interact with the active form of Rap2 (Taira et al., 2004; Nonaka et al., 2008). Recently, the E3 ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-1 was shown to modulate Rap2-mediated regulation of neurite development via binding to TNIK (Kawabe et al., 2010). However, MINK fails to mediate a ternary complex between Nedd4-1 and Rap2 (Kawabe et al., 2010), leaving the question as to how MINK regulates neuronal structure and function unclear.

To begin addressing this issue we analyzed whether MINK and Rap2 functionally interact within neurons. We used a cotransfection paradigm to test the effects of Rap2 on the localization of MINK and TNIK expressed in hippocampal neurons (Fig. 4; supplemental Fig. S3A, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Consistent with previously published results, constitutively active Rap2 (HA-Rap2(ca)) formed punctate clusters throughout the dendritic shaft and cell body, and caused the dendritic arbors to become severely stunted (Fig. 4A) (Fu et al., 2007). In contrast, overexpressed Flag-MINK, a kinase dead mutant form of MINK (Flag-MINK KD), and Flag-TNIK were diffusely distributed throughout dendrites, cell body and axons without apparent alteration in dendritic arborization (Fig. 4A,B; supplemental Fig. S3A, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Upon coexpression with HA-Rap2(ca), Flag-MINK, Flag-MINK KD, and Flag-TNIK each lost their diffuse cytoplasmic appearance and formed clusters throughout the shaft of the simplified dendritic arbors and within the cell body (Fig. 4A; supplemental Fig. S3A, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). In non-neuronal cells the interaction between active Rap2 and either MINK or TNIK is mediated via their C-terminal CNH domains (Taira et al., 2004; Nonaka et al., 2008). A truncated form of either MINK or TNIK lacking the CNH domain (MINK ΔCNH and TNIK ΔCNH, respectively) remained diffusely distributed throughout the entire cell in the presence or absence of HA-Rap2(ca) (Fig. 4A,B; data not shown). Collectively, these data corroborate the notion that functional interaction between activated Rap2 and either MINK or TNIK occurs in a CNH domain-dependent manner in hippocampal neurons.

Figure 4.

Activated Rap2 binds MINK in hippocampal neurons. A, Representative images of hippocampal neurons transfected with GFP and constitutively active Rap2 (HA-Rap2(ca)) and/or Flag-tagged MINK constructs as indicated (left). Scale bars, 50 μm. Representative 40 μm dendritic segments shown below each low-magnification image. B, Schematic diagram of wild-type MINK, kinase dead MINK (MINK KD) and MINK lacking CNH domain (MINK ΔCNH) constructs used for overexpression in neurons. C, Representative images of Rap2 mutant construct effects on dendritic clustering of endogenous staining for MINK/TNIK. Neurons were transfected with GFP and Rap2 dominant-negative [Rap2(dn)], Rap2(ca), or Rap2(ca) lacking its CAAX motif (Rap2(ca) ΔCAAX), and stained for endogenous MINK/TNIK. D, Bar graph of mean integrated intensity of dendritic MINK/TNIK clusters normalized to empty vector-transfected hippocampal neurons. Error bars indicate ±SEM. ***p < 0.001, relative to empty vector-transfected neurons, ANOVA. n ≥ 12 neurons for each. E, Representative images characterizing MINK/TNIK clusters induced by active Rap2. Neurons were transfected with HA-Rap2(ca) and stained for endogenous MINK/TNIK and syntaxin 6 as indicated. Scale bar, 50 μm. Representative 40 μm dendritic segments shown below each low-magnification image.

We reasoned that either the activation state of Rap2, and/or Rap2 association with the membrane might also modulate endogenous MINK and TNIK distribution. Ras family proteins require lipid modification of their C-terminal CAAX motif (C, cysteine; A, aliphatic; X, any residue) for targeting to membranes and for their appropriate signaling functions (Willumsen et al., 1984; Béranger et al., 1991; Hancock et al., 1991). Thus, we expressed dominant-negative Rap2 (Rap2(dn)), or constitutively active Rap2 with or without its CAAX motif (Rap2(ca) or Rap2(ca) ΔCAAX, respectively) in hippocampal cultures to examine their effects on endogenous MINK/TNIK (Fig. 4C). In cells expressing activated Rap2 there was a significant increase (∼40%) in the intensity of endogenous MINK/TNIK dendritic clusters, while Rap2(dn) caused a slight but significant reduction in endogenous MINK/TNIK cluster intensity relative to empty vector-transfected neurons (Fig. 4C,D). Overexpression of activated Rap2 lacking its CAAX motif failed to alter endogenous MINK/TNIK dendritic clusters (Fig. 4C,D). Thus, Rap2 bidirectionally modulates endogenous MINK/TNIK cluster intensity within dendrites, dependent upon its CAAX targeting motif.

Active Rap2 translocates from the plasma membrane to endosomes (Béranger et al., 1991; Uechi et al., 2009). Therefore, we examined the dendritic clusters induced by Rap2 activation on endogenous MINK/TNIK to determine whether these clusters may also localize to endosomes. We found that MINK/TNIK dendritic clusters partially colocalized with syntaxin-6, an endosomal marker of vesicles trafficking between the plasma membrane and trans-Golgi network (Fig. 4E) (Bock et al., 1997). Collectively our data are consistent with a functional interaction occurring between Rap2 and MINK/TNIK in neurons.

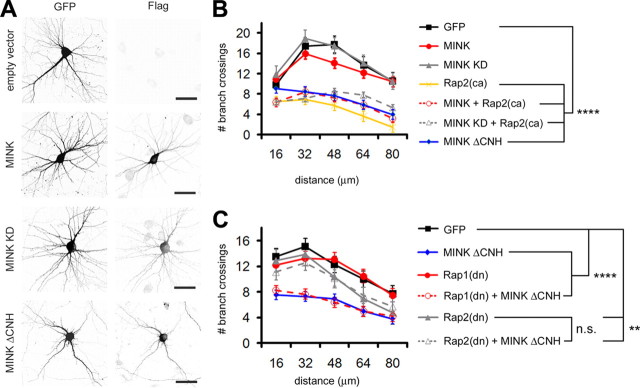

Rap2 activation is specifically required for truncated MINK (MINK ΔCNH) to reduce dendrite complexity

Activation of Rap2 signal transduction causes a severe reduction in neuronal branch complexity (Fu et al., 2007). The kinase function of TNIK has been implicated in this pathway, as expression of a kinase dead form of TNIK can disrupt Rap2-mediated impairment of dendritogenesis (Kawabe et al., 2010). To investigate whether MINK functions similarly in hippocampal neurons we ectopically expressed full-length MINK, MINK lacking kinase activity (MINK KD), or MINK missing the CNH domain (MINK ΔCNH; unable to interact with active Rap2) with and without Rap2(ca) (Fig. 5A,B) (Nonaka et al., 2008). Neurons were transfected after 18 DIV and processed following 3–4 d of overexpression. Neuronal morphology was visualized by cotransfected DsRed (Fig. 5A). Sholl analyses revealed that overexpression of either wild-type or kinase-dead MINK did not significantly alter overall dendritic arborization relative to GFP control (Fig. 5A,B). Expression of either Rap2(ca) alone or upon coexpression with MINK severely decreased the number of dendritic crossings over the entire measured distance where the few remaining primary branches (defined as number of dendrites directly emanating from the soma) displayed almost no secondary arbors (Fig. 5A,B). Unlike what was reported for kinase dead TNIK coexpression with Rap2(ca) (Kawabe et al., 2010), MINK KD failed to abrogate Rap2(ca)-mediated reduction in arborization (Fig. 5A,B). Surprisingly, expression of either a truncated MINK or TNIK that is unable to interact with Rap2 (MINK ΔCNH and TNIK ΔCNH, respectively) was sufficient to reduce branch complexity akin to that of Rap2(ca) expression alone (Fig. 5A,B; supplemental Fig. S3B, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material).

Figure 5.

MINKΔCNH-mediated reduction of dendritic complexity requires Rap2 activation. A, Representative images of hippocampal neurons transfected with GFP to visualize transfected cell morphology along with Flag-tagged constructs (indicated left). Scale bar, 50 μm. B, MINK ΔCNH compromises dendritic complexity. Neurons were transfected as indicated (right) and subjected to Sholl analysis (n ≥ 12 neurons for each). A significant difference between transfected groups was confirmed by a 7 × 5 mixed-effect ANOVA, with transfected group as the seven-level between-group effect and distance from the soma as the five-level within-group effect (F(6,574) = 54.051; p < 0.0001). Post hoc tests (PLSD) determined MINK ΔCNH alone, and Rap2(ca) either alone or with MINK or MINK KD each displayed significantly fewer dendritic branch point crossings relative to GFP control (****p < 0.0001). C, Rap2 activation is required for MINK ΔCNH to reduce dendritic arborization. Neurons were transfected as indicated (right) and subjected to Sholl analysis (n ≥ 12 neurons for each). A significant difference between transfected groups was confirmed by a 6 × 5 mixed-effect ANOVA, with transfected group as the six-level between-group effect and distance from the soma as the five-level within-group effect (F(5,504) = 31.438; p < 0.0001). Post hoc tests (PLSD) revealed expression of MINK ΔCNH alone, or MINK ΔCNH coexpressed with HA-Rap1(dn) both significantly reduced dendritic complexity relative to empty vector control (****p < 0.0001 for each relative to control). Dominant-negative Rap2 subtly decreased complexity relative to control (**p < 0.01 for each relative to control). However, when MINK ΔCNH was coexpressed with HA-Rap2(dn) the number of dendritic branch point crossings failed to decrease below the level of HA-Rap2(dn) expressed alone [p = 0.5673 for HA-Rap2(dn) expressed with MINK ΔCNH relative to HA-Rap2(dn) alone].

To directly test whether Rap2 function is involved in MINK ΔCNH- or TNIK ΔCNH-induced effects on synaptic structure we cotransfected hippocampal neurons with either MINK ΔCNH or TNIK ΔCNH and dominant-negative forms of either Rap1 (HA-Rap1(dn)) or Rap2 (HA-Rap2(dn)) to block endogenous Rap1 and Rap2 signaling, respectively. We found that cotransfection of HA-Rap1 (dn) did not affect the reduction in dendritic arborization induced by either MINK ΔCNH or TNIK ΔCNH expression (Fig. 5C; supplemental Fig. S3B, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Branch complexity was similarly reduced despite coexpression of Rap2 (dn) with TNIK ΔCNH, suggesting that TNIK ΔCNH-mediates its effects downstream of Rap2 activation (supplemental Fig. S3B, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). These data are consistent with previous findings suggesting that TNIK kinase activity functions downstream of Rap2 to modulate dendritogenesis (Kawabe et al., 2010). However, cotransfection of Rap2(dn) rescued the dendritic phenotype induced by MINK ΔCNH such that the level of branching did not differ significantly from that of Rap2(dn) expression alone (Fig. 5C). These data demonstrate that MINK ΔCNH-mediated arbor simplification depends upon Rap2 activation, while TNIK ΔCNH does not. Thus, MINK and TNIK can differentially impinge upon Rap2-mediated signal transduction where MINK may function upstream of Rap2 to regulate dendritic cytoarchitecture.

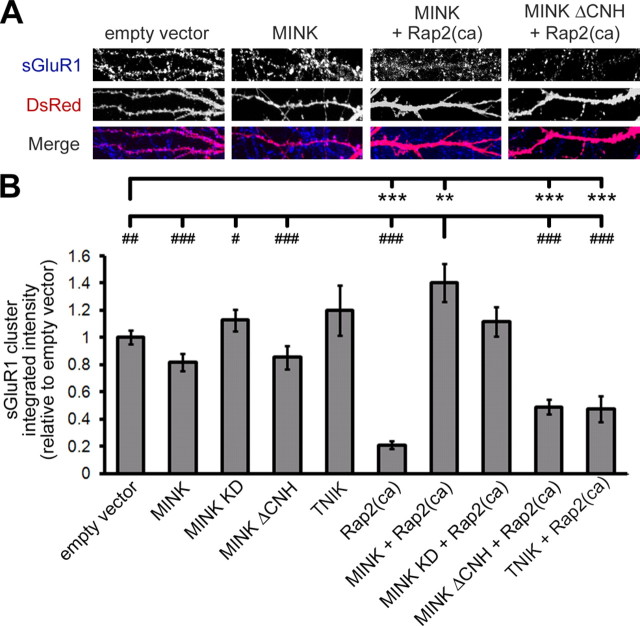

MINK blocks Rap2-mediated reduction in surface GluR1 clusters

In addition to its prominent role in regulating of neuronal structure, active Rap2 inhibits synaptic strength by decreasing surface AMPA-Rs (Zhu et al., 2005; Fu et al., 2007; Ryu et al., 2008). We determined that suppression of MINK expression also compromises dendritic arborization (Fig. 2B,C) and decreases AMPA-R function (Fig. 3B–F). In terms of a mechanism of action, these data led us to speculate that disruption of MINK's interaction with Rap2 allows for unrestricted Rap2-mediated signaling resulting in abrogated neuronal structure and function.

To directly test this hypothesis we asked whether MINK affects Rap2-mediated modulation of AMPA-Rs. When exogenously expressed in hippocampal neurons, neither TNIK, nor any of the MINK constructs examined (wild-type, kinase dead, ΔCNH) altered sGluR1 clusters in dendrites relative to empty vector-transfected cells (Fig. 6A,B). Consistent with previous findings, overexpression of active Rap2 alone caused a marked reduction in dendritic clustering of surface AMPA-Rs (Fig. 6B) (Zhu et al., 2005; Ryu et al., 2008). However, coexpression of either wild-type or kinase-dead MINK with active Rap2 completely abolished Rap2-mediated reduction in sGluR1 intensity (Fig. 6A,B). These data indicate that, in a kinase independent manner, MINK acts downstream of activated Rap2 to counteract its downregulation of surface AMPA-R expression. Additionally we determined that coexpression of active Rap2 with either TNIK or the MINK construct lacking its Rap2 interaction domain (MINK ΔCNH) failed to disrupt Rap2-mediated loss of sGluR1 (Fig. 6A,B). Collectively, our data indicate that MINK and TNIK may differentially impinge upon multiple aspects of Rap2-mediated signaling. Furthermore, they support the hypothesis that MINK interaction with active Rap2 can prevent Rap2-mediated decrease in surface AMPA-Rs.

Figure 6.

MINK disrupts Rap2-mediated regulation of surface GluR1 clusters. A, Representative images of MINK expression effects on Rap2-mediated reduction in surface AMPA receptor clusters. B, Quantification of mean sGluR1 cluster intensity in dendritic segments cotransfected with DsRed and pGW1 empty vector, or combinations of transfections as indicated (below graph). Mean cluster integrated intensities were normalized to empty vector control. Error bars indicate ±SEM, where **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 is relative to empty vector, and #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 is relative to MINK cotransfected with Rap2(ca), ANOVA. n ≥ 12 neurons for each.

Discussion

MINK and TNIK contain an N-terminal kinase domain, as well as noncatalytic domains that are involved in mediating protein-protein interaction. Based on structure–function analyses, it has been suggested that MINK and TNIK do not merely function as conventional kinases, but act primarily as scaffolds that assemble molecular complexes required for downstream signal transduction (Dan et al., 2001; Lim et al., 2003; Hu et al., 2004). While some MINK and TNIK protein interactors and phosphorylation targets have been identified (Fu et al., 1999; Dan et al., 2000; Taira et al., 2004; Nonaka et al., 2008; Mahmoudi et al., 2009; Kawabe et al., 2010), several pivotal questions regarding the function of these proteins remain unanswered. For instance, which signaling pathways depend on MINK and/or TNIK action, do these processes require that MINK and TNIK act as scaffolding molecules and/or as kinases, and moreover, which neuronal processes are influenced by MINK and TNIK? In this study, we establish that MINK and TNIK are enriched within PSDs and they act as critical modulators of synaptic structure and function. MINK and TNIK are required for normal synaptic density, dendrite complexity, as well as surface AMPA-R expression in hippocampal neurons. Moreover, we provide evidence to suggest that MINK and TNIK function distinctly to regulate Rap2-mediated signaling pathway(s).

Synaptic activity stimulates Rap2 activity (Heo and Meyer, 2003; Zhu et al., 2005; Fu et al., 2007). However, possible factors or conditions that modulate Rap2 signaling following its activation remain unclear. Candidate effectors of Rap2 include MINK and TNIK since they only bind the activated form of this GTPase (Taira et al., 2004; Nonaka et al., 2008). Indeed, TNIK is capable of binding the ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-1 to form a complex that regulates Rap2 signaling involved in neurite outgrowth (Kawabe et al., 2010). In contrast, MINK fails to interact with Nedd4-1. Thus, despite the fact that MINK is predicted to be more abundant within PSDs than TNIK (Peng et al., 2004), the significance of its interaction with Rap2 remains unclear. Here, we demonstrate that dendritic cluster intensity of MINK and TNIK is bidirectionally regulated by the activation state of Rap2 in neurons, where active Rap2 stimulates MINK/TNIK clustering. Our data also indicate that disruption of MINK or TNIK function allows for unbridled Rap2-mediated pruning of dendritic arbors. For instance, expression of either MINK or TNIK lacking their respective Rap2 interaction domain reduces neuronal complexity. Expression of the isolated kinase domain, but not full-length MINK, can activate the JNK signaling pathway which is implicated in Rap2-dependent depression of AMPA-R-mediated synaptic transmission (Lim et al., 2003; Zhu et al., 2005). Structure function analyses suggest that cis- or trans-interaction of MINK kinase domain with its C terminus maintains MINK in a folded conformation to thereby limit its basal kinase-mediated signaling (Lim et al., 2003). Thus, it is conceivable that MINK ΔCNH and TNIK ΔCNH harbor greater enzymatic activity than their full-length counterparts. These “kinase active” mutants might stimulate unregulated Rap2-mediated dendritic pruning. Indeed, the kinase function of TNIK has been shown to regulate dendritogenesis downstream of activated Rap2 via its interaction with Nedd4-1 (Kawabe et al., 2010). In contrast to TNIK, disruption of MINK kinase function had no effect on activated Rap2-mediated dendritic pruning. We also found that knockdown of MINK, TNIK, or both proteins simultaneously each resulted in dendritic pruning. In addition, MINK ΔCNH-mediated abrogation of dendritic complexity required activity of endogenous Rap2, while TNIK ΔCNH did not. These data suggest a mechanistic divergence in how MINK and TNIK function to regulate Rap2signaling pathway(s). An alternative mechanism for MINK's negative action on Rap2 could be that its CNH domain normally binds to and inhibits activated Rap2. Thus, in the case of reduced MINK expression activated Rap2 would become unleashed and able to transduce signals resulting in dendritic pruning. Based on structure function analyses, it is conceivable that expression of MINK ΔCNH acts as a dominant-negative on endogenous MINK. In this case, MINK ΔCNH might disrupt endogenous MINK targeting/interaction with, and inhibitory action upon, Rap2. Thus Rap2-mediated signal transduction leading to reduced neuronal complexity would be allowed to proceed unchecked. However, further analyses of the CNH-Rap2 interaction should elucidate the distinct mechanisms used by MINK ΔCNH and TNIK ΔCNH to regulate Rap2-mediated dendritic pruning.

In addition to regulating synaptic structure, activation of Rap2 effects synaptic transmission by reducing surface AMPA-Rs (Zhu et al., 2005; Fu et al., 2007; Kielland et al., 2009). In a study of young hippocampal cultures (14 d in vitro) Rap2 specifically reduced surface expression of the GluR2 AMPA-R subunit (Fu et al., 2007). Here we analyzed older hippocampal neurons (21–22 d in vitro) and found activated Rap2 abrogates surface GluR1 as well as GluR2 expression, consistent with previous findings (Zhu et al., 2005). The difference in specific AMPA-R subunits affected could arise from distinct maturity of neurons assayed and/or the specific AMPA-R antibodies used for surface expression analysis. Despite this difference it is clear that activated Rap2 critically regulates AMPA-R trafficking. Extending these studies we investigated whether MINK or TNIK also impinges on this aspect of Rap2-mediated signaling. We determined that the maintenance of surface GluR1 and GluR2 in dendritic spines requires expression of MINK or TNIK. However, rather than propagate Rap2-mediated signaling as has been described for TNIK (Kawabe et al., 2010) MINK appears to “gate” activated Rap2 signal transduction. Overexpression of MINK blocks Rap2-mediated removal of synaptic AMPA-Rs, whereas overexpression of TNIK had no effect. MINK's disruption of Rap2-mediated loss of AMPA-Rs is independent of its kinase activity, but requires the CNH domain that binds to Rap2, indicating that MINK likely functions as a scaffolding molecule that inhibits Rap2 signaling. Collectively, our findings provide evidence for a novel signaling mechanism whereby an “effector” protein functionally “gates” the signal transduction for its cognate GTPase. While overexpression of MINK ΔCNH alone was sufficient to decrease dendritic complexity, it was not sufficient to affect surface GluR1 levels. Precisely how MINK achieves separable effects on distinct branches of Rap2-mediated signal transduction (i.e., regulation of dendritic complexity and surface AMPA-Rs) should be clarified by further analyses of the MINK-Rap2 interaction.

Abnormal synaptic morphology has been associated with neurological disorders including mental retardation, epilepsy, Alzheimer's and schizophrenia (McGlashan and Hoffman, 2000; Chelly and Mandel, 2001; Coleman and Yao, 2003; Lewis et al., 2003; Rund, 2009). Our observations suggest that precise coregulation of the actors in the MINK-Rap2 signal transduction pathway is required to maintain the integrity of neuronal morphology and function. Recently, human TNIK was identified in a genome-wide screen for single-nucleotide polymorphisms associated with schizophrenia, and found to bind directly to Disrupted in Schizophrenia 1 (DISC1), which is itself a schizophrenia risk gene (Camargo et al., 2007; Potkin et al., 2009; Shi et al., 2009). Whether or not the closely related protein MINK shares a link to schizophrenia or diverges from TNIK-mediated signaling in this respect remains unknown.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant MH076936 (M.S.), and a Long-Term Fellowship from the Human Frontier Science Program Organization (N.K.H.), as well as the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (N.K.H.). M.S. was investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. We thank Elizabeth Ramm for excellent technical assistance and Drs. V. Anggono, D. Edbauer, D. T. Lin, G. Thomas, and G. Scita for critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- Bear MF, Malenka RC. Synaptic plasticity: LTP and LTD. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1994;4:389–399. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(94)90101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béranger F, Tavitian A, de Gunzburg J. Post-translational processing and subcellular localization of the Ras-related Rap2 protein. Oncogene. 1991;6:1835–1842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss TV, Collingridge GL. A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature. 1993;361:31–39. doi: 10.1038/361031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock JB, Klumperman J, Davanger S, Scheller RH. Syntaxin 6 functions in trans-Golgi network vesicle trafficking. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1261–1271. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.7.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. AMPA receptor trafficking at excitatory synapses. Neuron. 2003;40:361–379. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00640-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo LM, Collura V, Rain JC, Mizuguchi K, Hermjakob H, Kerrien S, Bonnert TP, Whiting PJ, Brandon NJ. Disrupted in Schizophrenia 1 Interactome: evidence for the close connectivity of risk genes and a potential synaptic basis for schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:74–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelly J, Mandel JL. Monogenic causes of X-linked mental retardation. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:669–680. doi: 10.1038/35088558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman PD, Yao PJ. Synaptic slaughter in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:1023–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collingridge GL, Isaac JT, Wang YT. Receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:952–962. doi: 10.1038/nrn1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins MO, Husi H, Yu L, Brandon JM, Anderson CN, Blackstock WP, Choudhary JS, Grant SG. Molecular characterization and comparison of the components and multiprotein complexes in the postsynaptic proteome. J Neurochem. 2006;97(Suppl 1):16–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan I, Watanabe NM, Kobayashi T, Yamashita-Suzuki K, Fukagaya Y, Kajikawa E, Kimura WK, Nakashima TM, Matsumoto K, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Kusumi A. Molecular cloning of MINK, a novel member of mammalian GCK family kinases, which is up-regulated during postnatal mouse cerebral development. FEBS Lett. 2000;469:19–23. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01247-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan I, Watanabe NM, Kusumi A. The Ste20 group kinases as regulators of MAP kinase cascades. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:220–230. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)01980-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu CA, Shen M, Huang BC, Lasaga J, Payan DG, Luo Y. TNIK, a novel member of the germinal center kinase family that activates the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway and regulates the cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30729–30737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Z, Lee SH, Simonetta A, Hansen J, Sheng M, Pak DT. Differential roles of Rap1 and Rap2 small GTPases in neurite retraction and synapse elimination in hippocampal spiny neurons. J Neurochem. 2007;100:118–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock JF, Cadwallader K, Paterson H, Marshall CJ. A CAAX or a CAAL motif and a second signal are sufficient for plasma membrane targeting of ras proteins. EMBO J. 1991;10:4033–4039. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04979.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley JG. AMPA receptor trafficking pathways and links to dendritic spine morphogenesis. Cell Adh Migr. 2008;2:276–282. doi: 10.4161/cam.2.4.6510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo WD, Meyer T. Switch-of-function mutants based on morphology classification of Ras superfamily small GTPases. Cell. 2003;113:315–328. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00315-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Leo C, Yu S, Huang BC, Wang H, Shen M, Luo Y, Daniel-Issakani S, Payan DG, Xu X. Identification and functional characterization of a novel human misshapen/Nck interacting kinase-related kinase, hMINK beta. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54387–54397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404497200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain NK, Yamabhai M, Ramjaun AR, Guy AM, Baranes D, O'Bryan JP, Der CJ, Kay BK, McPherson PS. Splice variants of intersectin are components of the endocytic machinery in neurons and nonneuronal cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15671–15677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan BA, Fernholz BD, Boussac M, Xu C, Grigorean G, Ziff EB, Neubert TA. Identification and verification of novel rodent postsynaptic density proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:857–871. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400045-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabe H, Neeb A, Dimova K, Young SM, Jr, Takeda M, Katsurabayashi S, Mitkovski M, Malakhova OA, Zhang DE, Umikawa M, Kariya K, Goebbels S, Nave KA, Rosenmund C, Jahn O, Rhee J, Brose N. Regulation of Rap2A by the ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-1 controls neurite development. Neuron. 2010;65:358–372. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielland A, Bochorishvili G, Corson J, Zhang L, Rosin DL, Heggelund P, Zhu JJ. Activity patterns govern synapse-specific AMPA receptor trafficking between deliverable and synaptic pools. Neuron. 2009;62:84–101. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA, Glantz LA, Pierri JN, Sweet RA. Altered cortical glutamate neurotransmission in schizophrenia: evidence from morphological studies of pyramidal neurons. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1003:102–112. doi: 10.1196/annals.1300.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J, Lennard A, Sheppard PW, Kellie S. Identification of residues which regulate activity of the STE20-related kinase hMINK. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;300:694–698. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02909-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi T, Li VS, Ng SS, Taouatas N, Vries RG, Mohammed S, Heck AJ, Clevers H. The kinase TNIK is an essential activator of Wnt target genes. EMBO J. 2009;28:3329–3340. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinow R, Malenka RC. AMPA receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:103–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty N, Paust S, Ikizawa K, Dan I, Li X, Cantor H. Signaling by the kinase MINK is essential in the negative selection of autoreactive thymocytes. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:65–72. doi: 10.1038/ni1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlashan TH, Hoffman RE. Schizophrenia as a disorder of developmentally reduced synaptic connectivity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:637–648. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.7.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto E. Molecular mechanism of neuronal plasticity: induction and maintenance of long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. J Pharmacol Sci. 2006;100:433–442. doi: 10.1254/jphs.cpj06007x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka H, Takei K, Umikawa M, Oshiro M, Kuninaka K, Bayarjargal M, Asato T, Yamashiro Y, Uechi Y, Endo S, Suzuki T, Kariya K. MINK is a Rap2 effector for phosphorylation of the postsynaptic scaffold protein TANC1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:573–578. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J, Kim MJ, Cheng D, Duong DM, Gygi SP, Sheng M. Semiquantitative proteomic analysis of rat forebrain postsynaptic density fractions by mass spectrometry. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21003–21011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400103200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potkin SG, Turner JA, Guffanti G, Lakatos A, Fallon JH, Nguyen DD, Mathalon D, Ford J, Lauriello J, Macciardi F. A genome-wide association study of schizophrenia using brain activation as a quantitative phenotype. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:96–108. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rund BR. Is there a degenerative process going on in the brain of people with schizophrenia? Front Hum Neurosci. 2009;3:36. doi: 10.3389/neuro.09.036.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu J, Futai K, Feliu M, Weinberg R, Sheng M. Constitutively active Rap2 transgenic mice display fewer dendritic spines, reduced extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling, enhanced long-term depression, and impaired spatial learning and fear extinction. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8178–8188. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1944-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeburg DP, Sheng M. Activity-induced Polo-like kinase 2 is required for homeostatic plasticity of hippocampal neurons during epileptiform activity. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6583–6591. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1853-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd JD, Huganir RL. The cell biology of synaptic plasticity: AMPA receptor trafficking. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:613–643. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Levinson DF, Duan J, Sanders AR, Zheng Y, Pe'er I, Dudbridge F, Holmans PA, Whittemore AS, Mowry BJ, Olincy A, Amin F, Cloninger CR, Silverman JM, Buccola NG, Byerley WF, Black DW, Crowe RR, Oksenberg JR, Mirel DB, et al. Common variants on chromosome 6p22.1 are associated with schizophrenia. Nature. 2009;460:753–757. doi: 10.1038/nature08192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sholl DA. Dendritic organization in the neurons of the visual and motor cortices of the cat. J Anat. 1953;87:387–406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stornetta RL, Zhu JJ. Ras and Rap Signaling in Synaptic Plasticity and Mental Disorders. 2010 doi: 10.1177/1073858410365562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taira K, Umikawa M, Takei K, Myagmar BE, Shinzato M, Machida N, Uezato H, Nonaka S, Kariya K. The Traf2- and Nck-interacting kinase as a putative effector of Rap2 to regulate actin cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49488–49496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406370200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinidad JC, Thalhammer A, Specht CG, Lynn AJ, Baker PR, Schoepfer R, Burlingame AL. Quantitative analysis of synaptic phosphorylation and protein expression. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:684–696. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700170-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uechi Y, Bayarjargal M, Umikawa M, Oshiro M, Takei K, Yamashiro Y, Asato T, Endo S, Misaki R, Taguchi T, Kariya K. Rap2 function requires palmitoylation and recycling endosome localization. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;378:732–737. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.11.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willumsen BM, Christensen A, Hubbert NL, Papageorge AG, Lowy DR. The p21 ras C-terminus is required for transformation and membrane association. Nature. 1984;310:583–586. doi: 10.1038/310583a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JJ, Qin Y, Zhao M, Van Aelst L, Malinow R. Ras and Rap control AMPA receptor trafficking during synaptic plasticity. Cell. 2002;110:443–455. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00897-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Pak D, Qin Y, McCormack SG, Kim MJ, Baumgart JP, Velamoor V, Auberson YP, Osten P, van Aelst L, Sheng M, Zhu JJ. Rap2-JNK removes synaptic AMPA receptors during depotentiation. Neuron. 2005;46:905–916. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]