Abstract

Objectives

This investigation examined the associations between self-reports, collateral-source reports and a clinician’s diagnosis of depression in persons with cognitive impairment.

Method

Responses on the Geriatric Depression Scale – 15 (GDS-15) from 162 participants with a diagnosis of Mild Cognitive Impairment (n = 78) or Alzheimer’s Dementia and a Mini-Mental State score ≥15 (n = 84) were compared with both their collateral sources’ report on either the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (n = 93) and/or the collateral-source GDS-15 (n = 67), or a clinician’s diagnosis of Major Depression (MD).

Results

Significant differences were seen between self- versus collateral-source reports of depression in these participants. Participants’ reports of loss of interest (anhedonia) significantly increased the odds of disagreement with their collateral sources (OR = 3.78, 95% CI: 1.3–11.2) while reports of negative cognitions significantly decreased the odds of such a disagreement (OR = 0.31, 95% CI: 0.1–0.9). The symptom of anhedonia also showed the strongest association with the clinician’s diagnosis of MD.

Conclusion

A motivational symptom like loss of interest was seen to play an important role in depression experienced by those with cognitive impairment.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, depression, dementia, mild cognitive impairment

Introduction

Diagnosing depression in the presence of cognitive impairment has been fraught with difficulties. Significant differences have been noted in the report of symptoms by patients compared to the report of their accompanying spouses, family members, or informed associates (collateral sources) (Burke et al., 1998; Chemerinski, Petracca, Sabe, Kremer, & Starkstein, 2001; Gilley, Wilson, Fleischman, & Harrison, 1995; Moye, Robiner, & Mackenzie, 1993). Most studies have found that collateral sources are likely to report more symptoms than the patients themselves. Hence, prevalence estimates of depression in patients with dementia have varied widely depending upon whether the information was collected from the patients or their accompanying collateral sources (Mackenzie, Robiner, & Knopman, 1989).

A recent, methodologically rigorous, study to establish the prevalence of major depression (MD) in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) attempted to overcome this limitation by interviewing both the subjects and their collateral sources together, and by using information from as many sources as possible to establish the presence of symptoms in study participants (Zubenko et al., 2003). Any discrepancy in the report of symptoms between study participants and their collateral sources was resolved by an elaborate process of arriving at a consensus. Such a time-consuming procedure might not be possible at all times, especially in routine clinical settings. Hence, it would be valuable to examine which symptoms are commonly associated with the differences in reports about depression, as this information could help investigators develop an optimal way of diagnosing depression in persons with cognitive impairment.

Possibly due to these differences in reporting, the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) now requires that the presence of depression be assessed from both participants and their collateral sources. The NACC coordinates information from all the Alzheimer’s disease Centers (ADCs) in the United States. It serves as a national repository of information about participants with dementia and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) that are followed longitudinally at these ADCs (Beekly et al., 2004). The two instruments currently used are the 15-item version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) enquiring about symptoms of depression from ADC participants (Sheikh & Yesavage, 1986), and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q) evaluating the collateral source’s global impression about the presence and severity of depression in those participants (Kaufer et al., 2000). Although this two-source assessment for depression appears intuitively to be a move in the right direction, there is only limited information of how the combined use of these instruments compares vis-à-vis a clinician’s diagnosis of depression in this population.

Another difficulty associated with diagnosing depression in those with cognitive impairment is a relative lack of consensus about the optimal set of criteria that can be used to diagnose depression in the presence of dementia. In 2002, a panel of experts on dementia and late-life depression met at a workshop convened by the National Institute of Mental Health. After deliberating about the existing evidence regarding depression coexisting with dementia, they proposed a set of provisional diagnostic criteria for the category of depression in Alzheimer’s disease in hopes of stimulating further research and validation of the syndrome (Olin et al., 2002). The expert panel called for further definition and refinement of the syndrome of depression in the presence of dementia (Olin, Katz, Meyers, Schneider, & Lebowitz, 2002).

Identifying those symptoms of depression that are commonly associated with disagreement between the patients’ and their collateral sources’ reports of depression can help delineate an optimal criteria set to be used to diagnose depression. Earlier research has found that certain symptoms, like loss of interest or poor energy, are likely to be more frequent when there is a difference between patients’ and their caregivers’ reports (Mackenzie et al., 1989). Similarly, examining the symptoms that are commonly used by clinicians to diagnose depression in patients with MCI or early AD can help refine the diagnostic criteria for this syndrome. Such an examination gains importance because researchers recently demonstrated that symptoms such as loss of confidence or self-esteem contributed significantly to a disagreement about the presence of depression between the different diagnostic criteria in use to diagnose depression with dementia (Vilalta-Franch et al., 2006). This study also found that there was, at best, only a modest correlation between the different criteria currently in use to diagnose depression in the presence of cognitive impairment.

In order to elucidate some answers to the diagnostic dilemmas described above, we conducted a study with the following specific aims: (1) Examine the agreement between ADC participants with cognitive impairment and their collateral sources with regards screen positive for depression, and also for agreement on individual questions of the GDS-15. (2) Identify specific symptoms that were significantly more likely to be associated with a disagreement between participants and their collateral sources regarding a positive screen for depression. (3) Identify symptoms of depression that were significantly more likely to be associated with clinicians establishing a diagnosis of depression in persons with cognitive impairment.

Methods

Settings and subjects

Our participants were community-residing volunteers at the ADC of a university medical center in Arkansas. Each participant was required to be accompanied by a reliable collateral source, who had been prescreened with questions about the amount of time that he or she usually spent in direct personal contact with the participants. Thus, collateral sources were mostly family members, and rarely, other close associates who were familiar with the participants’ activities and functioning over the past few months. All participants and their accompanying collateral sources signed a detailed informed consent that had been approved by the Institutional Review Board. These participants and their collateral sources then assigned to meet separately with different members of the ADC team according to an approved uniform protocol. Subsequently, physicians at the ADC, which included neurologists, a geriatrician and a geriatric psychiatrist, interviewed the participant and his/her collateral source together and performed a neurological examination of the participant.

These participants were then adjudicated by the ADC team during a weekly multi-disciplinary consensus conference to be cognitively normal or to have a research consensus diagnosis of dementia according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria for this category (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), AD according to the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria (McKhann et al., 1984), or MCI according to the criteria proposed by Winblad et al. (2004). The NACC recommends the use of these criteria to establish the respective diagnoses. This report analyzes first-year data from participants diagnosed with AD or MCI who had their initial evaluation, since the ADC’s inception in November 2001 till the end of May 2006.

Measures

The NACC requires that a number of different rating scales and questionnaires be administered to every ADC participant. However, data from all evaluating instrument might not be available from each and every participant or their collateral source. We analyzed site-specific data from only the following three instruments for the purpose of this report:

The Geriatric Depression Scale – 15 item

The GDS is a series of 15 ‘Yes/No’ response questions inquiring about the presence of different symptoms of depression (Sheikh & Yesavage, 1986). It was designed to decrease the reliance on the somatic symptoms of depression because of the presence of multiple comorbid medical problems in the elderly. The scale has demonstrated reliability and validity coefficients >0.8, indicating that it provides a reliable assessment of the presence of depression (Yesavage et al., 1982). The GDS-15 is usually self-rated by participants themselves, but has also been completed by participants with the help of a research technician. One recent study has examined the depression-screening psychometric properties of this instrument in the oldest old with significant cognitive impairment (de Craen, Heeren, & Gussekloo, 2003). Investigators have used threshold scores between 3 and 5 for the purposes of screening for the presence of depression (Watson & Pignone, 2003). A score of ≥4 has been used as the operating threshold for a positive screen for depression on the GDS-15 at our center and for the purposes of this investigation.

The Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire

The NPI-Q is a brief, informant-based assessment of 12 neuropsychiatric symptom domains, like delusions, hallucinations or depression, in patients with dementia (Kaufer et al., 2000). The collateral sources rate the presence or absence of the symptom over the previous month on each domain subscale. The NPI subscales have shown significant validity and reliability, and have been very useful in characterizing psychopathology of dementia syndromes (Cummings et al., 1994). In this study, the Depression subscale demonstrated a concurrent validity correlation of 0.62 (p = 0.01) with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS; Hamilton, 1960) and a validity correlation coefficient of 0.33 (p = 0.05) with the Affective Disturbance subscale of the Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale (BEHAVE-AD; Reisberg et al., 1987). The NPI subscales have also been shown to be sensitive to treatment effects and amelioration of behavioral symptoms of dementia with pharmacological agents (Cummings, 1997). The Depression subscale of the NPI-Q consists of a single item that assesses the collateral source’s global impression about the presence or absence of depression in the participant. If reported to be present, the degree of depression is rated on a severity scale from 1 to 3. Hence, responses on this subscale have been used in recent reports as the collateral source’s report of the presence of depression in patients with dementia (Cummings, McRae, Zhang, & Donepezil-Sertraline Study Group, 2006; Vilalta-Franch et al., 2006).

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)

The MMSE was developed to provide a brief assessment and measure of a person’s cognitive functioning (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975), and has been used extensively in research with cognitively impaired subjects. MMSE scores at the time of assessment have been used as a measure of impairment in participants’ cognitive functions. Because the GDS-15 has been shown to have only limited reliability and validity in those with more severe cognitive impairment (McGivney, Mulvihill, & Taylor, 1994), only MCI and AD participants with an MMSE of ≥15 were included for the purpose of the current analysis.

Procedure

ADC participants were evaluated using a structured neuropsychological battery of tests, which included completing the GDS-15 questions, either independently or with assistance from the ADC staff. At the same time but separately from the participants, the accompanying collateral sources indicated their observation of the occurrence and/or severity of neuropsychiatric symptoms that they might have observed during the previous month on the NPI-Q. Finally, both participants and collateral sources met with the ADC physician who interviewed them together using a semi-structured interview format. The physicians made a clinical diagnosis of major depression during this evaluation when participants were determined to have symptoms meeting DSM-IV criteria for this category. The physician did not have information from either the GDS-15 or the NPI-Q at the time of this interview. This process allowed us the opportunity to compare the participants’ independent reports of depression (GDS-15) and the collateral sources’ independent report of depression (NPI-Q) prior to the clinicians’ interview for the presence of MD.

During the first few months of our ADC’s existence, the accompanying collateral sources provided information about the participant on both the NPI-Q and the GDS-15. Subsequently, however, to ensure uniformity of information gathered across all ADCs nationally, new NACC guidelines required that that the collateral sources’ reports about neuropsychiatric symptoms be collected on the NPI-Q only. Thus, the practice of collecting data on both the NPI-Q and the collateral-source GDS-15 (hereafter referred to as CollGDS) was discontinued at our ADC and nationwide as part of a move to streamline data-collecting procedures. Therefore, data on the CollGDS were available only for around the first 67 participants.

A disagreement between the participant and their collateral source occurred when the participant screened positive (GDS-15 ≥ 4) by self-report, but not by the collateral source’s report (NPI-Q-Depression ≥1), or vice-versa. Conversely, participants and collateral sources were considered to be in agreement for this analysis when screens from both the sources were either positive or negative for depression. A number of recent studies have examined such associations of disagreement (Erkinjuntti, Ostbye, Steenhuis, & Hachinski, 1997; Vilalta-Franch et al., 2006).

Next, we were interested in examining whether specific participant-reported symptoms of depression could be identified that were significantly associated with either a disagreement between reports from the two sources or with the clinicians’ diagnosis of depression. Hence, the presence of individual symptoms of depression was determined from the participants’ responses to the different participant reported GDS-15 questions. The ADC geriatric psychiatrist (MPC) reviewed the GDS-15 questions and grouped them as follows to ascertain whether a particular symptom was reported or not:

sad or depressed mood – Q 5 and Q 7,

loss of interest or anhedonia – Q 2 and Q 4,

loss of energy or fatigue – Q 13,

death wishes or suicidal ideation – Q 1 and 11, and

negative cognitions (hopelessness, helplessness, worthlessness) – Q 8, Q 12, Q 14 and Q 15.

The symptom was recorded as being present if the participant responded positively to any of the questions for that symptom. Thus, the symptom was recorded as absent only if the participant answered all the questions about that particular symptom negatively.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics included frequencies for categorical variables like sex and race, and means and standard deviations (SDs) for continuous measures, like age and MMSE scores. Fisher’s exact tests were used to assess associations between categorical variables. Student’s t-tests were used to compare means of continuous measures between groups and adjustments for repeated-measures were made where appropriate. Agreement between participants and their collateral sources on the depression-screening measures and on individual questions of the GDS-15 was evaluated with the kappa (κ) coefficient. If there was no evidence of agreement between the participants and their collateral sources, we then tested whether the two sources disagreed. As the screens for depression were paired-observations about the same participant, the proportions of participants screening positive by self- versus collateral-reports were compared using the McNemar’s test.

Logistic regression models were used to examine the contribution of individual clinical symptoms toward a disagreement between positive screens for depression by self-reports compared to the collateral sources’ reports of the presence of depression. The dependent variable for disagreement had a value of zero when the two sources were in agreement about the presence or absence of depression, and a value of one when they disagreed. Similar logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the role of individual symptoms regarding the clinician’s diagnosis of depression. All analyses were two tailed and the level of statistical significance was set at 0.05. Statistical routines and analyses were carried out using the SAS ® (version 9.1).

Results

The demographic and baseline characteristics of the MCI and AD participants with an MMSE ≥15 are presented in Table 1. Significant differences were found between participants with MCI and those with AD on age, MMSE scores and proportion of whites, but not on other baseline characteristics examined. Frequencies of the different symptoms of depression were also not found to be different in participants with MCI compared to those with AD. Hence, MCI and AD participants were considered together for all subsequent analyses. Also, participants with the CollGDS data were found to be not different on baseline characteristics from those who had information only on the NPI-Q. Therefore, participants with only the NPI-Q data and those with both NPI-Q and CollGDS were treated as not coming from two different populations for these analyses. These data are not presented due to limitations of space.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics of participants with MCI and AD in the current report.

| MCI | Dementia | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 78 | 84 | 162 |

| Age yrs (±SD)a | 74.4 (8.0) | 79.5 (8.7) | 77.1 (± 8.7) |

| (Range) | (53–93) | (52–94) | (52–94) |

| Female gender (%) | 47 (60.3%) | 46 (54.1%) | 93 (57.4%) |

| Race (%) | |||

| Whiteb | 43 (55.1%) | 62 (73.8%) | 105 (64.8%) |

| African-American | 35 (44.9%) | 22 (26.2%) | 57 (35.2%) |

| Married (%) | 50 (64.1%) | 45 (53.6%) | 95 (58.6%) |

| Education yrs (±SD) | 14.1 (3.2) | 13.4 (3.1) | 13.7 (3.2) |

| (Range) | (5–20) | (5–20) | (5–20) |

| MMSE score (±SD)c | 26.4 (2.6) | 21.9 (4.0) | 24.0 (4.1) |

| (Range) | (19–30) | (15–29) | (15–30) |

Notes: (±SD): standard deviation; (%): percentage.

(mean difference = 5.1, t = 3.90, df = 160, p < 0.001);

(proportion white difference = 18.7%, Fisher’s exact test p = 0.014);

(mean difference = 4.50, t = 8.48, df = 160, p < 0.001).

The number of participants screening positive for depression by the self-, or the two collateral-source-reported measures (CollGDS and NPI-Q) are presented in Table 2. Thirteen of the sixty-seven patients (19.4%) with both a self- and collateral-source GDS-15 screened positive per their own report, as opposed to 33 (49.2%) screening positive per their collateral source’s report. The kappa (κ) coefficient of agreement between the self- and collateral-source screens was −0.085 (95% CI: −0.274–0.105; p = 0.383). Since there was no evidence that these sources agreed, we then tested whether they disagreed. The two proportions screening positive by the GDS-15 and the CollGDS were significantly different from each other (McNemar’s χ2(1) = 11.11, p < 0.001). Of the 93 participants having data from both a participant GDS-15 and a collateral-source NPI-Q, only 18 (19.4%) screened positive by self-report compared to 41 (44.1%) per the collateral sources’ report on the NPI (Table 2). The agreement between these two reports had a κ coefficient = 0.28 (95% CI: 0.109–0.453; p = 0.001). Sixty collateral sources completed both the CollGDS and the NPI-Q. Of these, 31 (52.5%) gave a positive screen for depression on the CollGDS and 24 (40.7%) on the NPI-Q. The intra-collateral-source agreement coefficient of κ = 0.172 (95% CI: −0.069–0.414; p = 0.163) was not significant. However, there was also no evidence that collateral sources were inconsistent in their reports on the CollGDS and NPI-Q (McNemar’s χ2(1) = 1.96, p = 0.162).

Table 2.

Relative agreement between different approaches to screen for and diagnose depression in participants with MCI and AD.

| Participant reports depression (GDS ≥ 4) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Absent | Present | ||

| Collateral–source GDS depression (n = 67) |

Absent | 26 (38.8%) |

8 (11.9%) |

| Present | 28 (41.8%) |

5 (7.5%) |

|

| Collateral–source NPI depression (n = 93) |

Absent | 48 (51.6%) |

4 (4.3%) |

| Present | 27 (29%) |

14 (15.1%) |

|

| Clinician’s Diagnosis of depression (n = 162) |

Absent | 123 (75.9%) |

19 (11.7%) |

| Present | 4 (2.5%) |

16 (9.9%) |

|

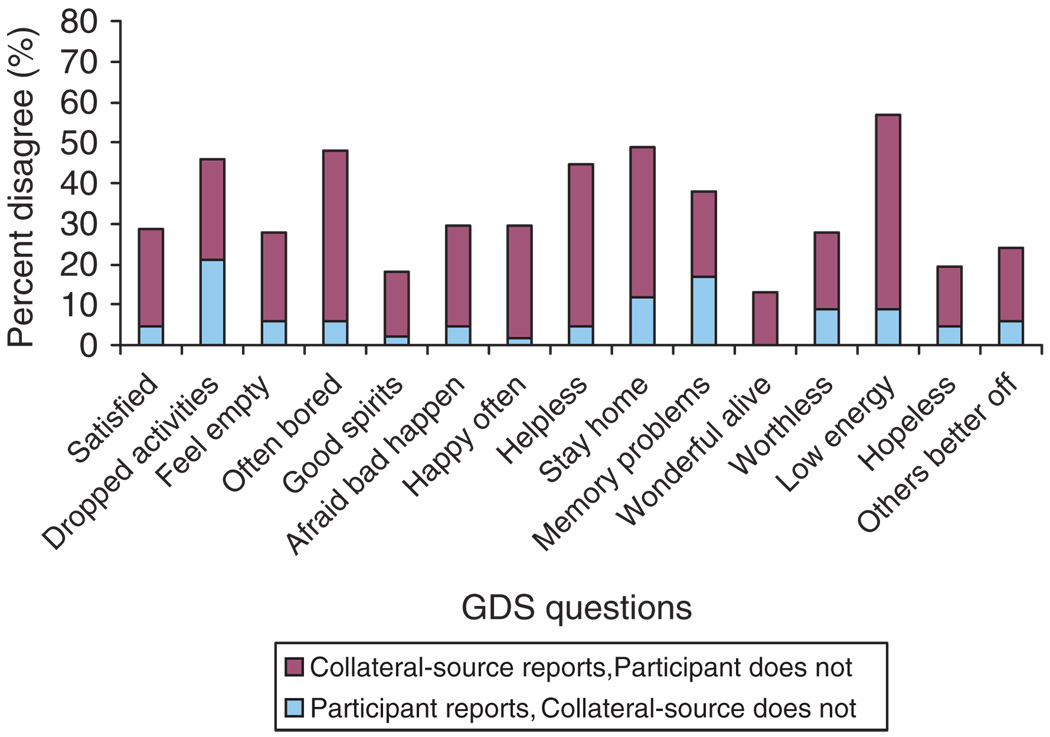

There was no evidence of agreement between participants and their collateral sources on individual questions on the GDS-15, except on Q 10: ‘Do you feel you have more problems with your memory than most?’ (κ = 0.24, 95% CI: 0.009–0.476; p = 0.042). Eleven of the remaining fourteen questions were significantly discrepant, while Q2 (dropped many activities and interests), Q12 (feel pretty worthless) and Q14 (feel situation is hopeless) were not. The percent disagreements between the two reports on the individual GDS-15 questions are shown in Figure 1. As part of a comparison of the total GDS-15 scores from the two sources of assessment, the mean GDS-15 score in the 13 participants screening positive by self-report was found to be 6.05 (±2.08). This was significantly lower than the mean CollGDS score of 8.09 (±3.60) in the 33 participants screening positive by collateral-source reports (mean difference = 2.04, t(49.1) = 2.94, p = 0.005).

Figure 1.

Percent disagreement between participants and collateral sources on individual GDS-15 questions.

Notes: Lighter color (blue) – participant reports but collateral source does not, Darker color (maroon) – collateral source reports but participant does not.

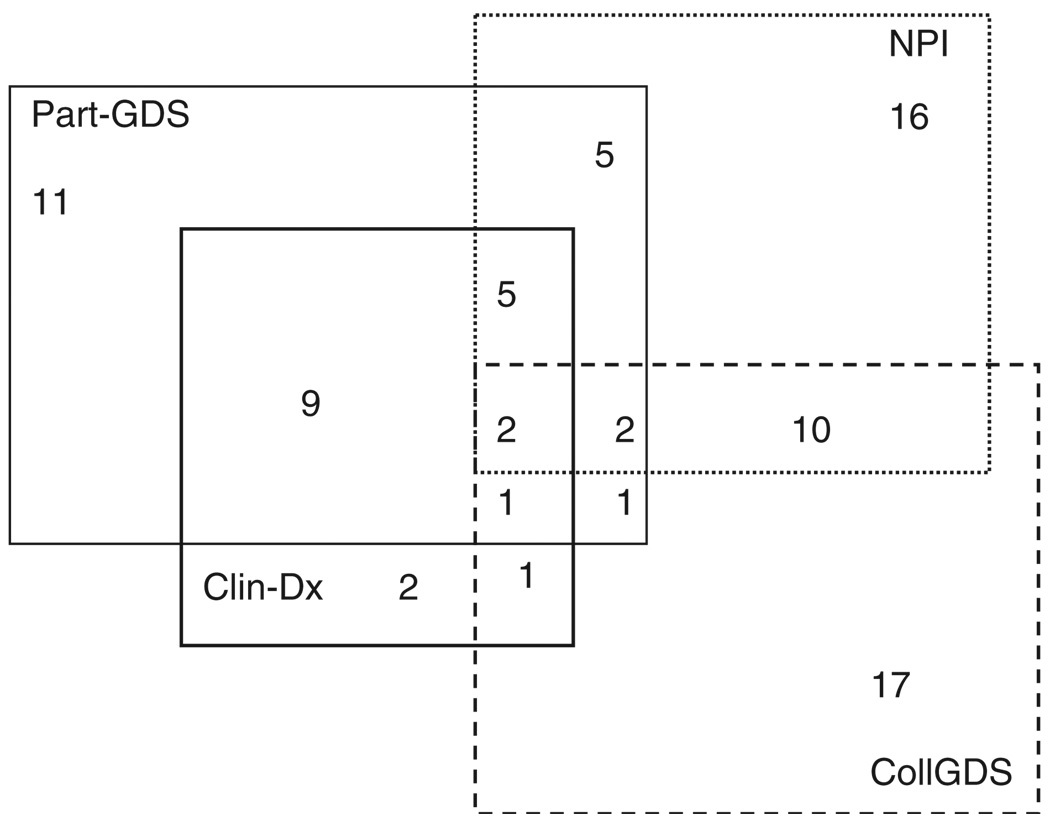

A clinician’s diagnosis of the presence of MD was made in 20 of 161 (12.4%) participants, as data regarding clinician’s diagnosis was missing for one participant (Table 2). The overlap of participants clinically diagnosed with depression with those identified through the different screening methods is presented in Figure 2. Our next step was to examine which screening method showed the strongest association with the clinician’s diagnosis of MD. We began with univariate logistic regressions for each of the three methods individually with the clinician’s diagnosis, and found that the self-reported GDS-15 showed a strong association (Odds Ratio (OR) = 25.7, 95% CI = 7.8–85.1, Wald χ2(1) = 28.2, p < 0.001), while the collateral source NPI-Q demonstrated a modest independent association (OR = 4.2, 95% CI = 1.03–16.9, Wald χ2(1) = 3.9, p = 0.046) with the clinician’s diagnosis. The CollGDS did not show any association with the clinician’s diagnosis of MD in the participants.

Figure 2.

Participants screening positive and diagnosed with depression according to different assessments.

Notes: Part-GDS, Participant reported GDS-15; NPI, Collateral-source Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Q; CollGDS, Collateral Source GDS-15; Clin-Dx, Clinician’s Diagnosis of Depression by physicians.

As the next step, we entered the self-reported GDS-15 and the collateral-source NPI-Q along with their interaction term into a multi-variate logistic regression model using clinical depression diagnosis as the dependent variable. In this model, only the self-reported GDS-15 was found to be significantly associated with the clinician’s diagnosis (OR = 32.7, 95% CI = 5.4–199.1, Wald χ2(1) = 14.3, p < 0.001). Neither the NPI-Q nor the interaction between the two showed any significant association. Modeling clinician’s diagnosis of depression as a function of the total self-reported GDS-15 score showed that the odds of a clinical diagnosis increased 1.7 times (95% CI = 1.4–2.0, Wald χ2(1), p < 0.001) for each one-point increase in the total self-reported GDS score.

Our next aim was to identify specific symptoms that might be associated with either a disagreement between the two reports, or a clinician’s diagnosis of depression. In a multivariate logistic regression, we first examined the relative associations between the participants’ self-reports of different depressive symptoms with a disagreement between participants and their collateral sources regarding screening positive for depression, as described earlier. The conditional ORs from these analyses are presented in Table 3. The odds of disagreement between participants and their collateral sources were seen to increase significantly by participants’ report of loss of interest or anhedonia. Conversely, they were seen to decrease significantly by their self-report of negative cognitions. In a similar multivariate model examining the relative association of the individual symptoms on the diagnosis of MD, only loss of interest was significantly associated with a clinician’s diagnosis (Table 3). It was estimated that, reports of all other symptoms remaining the same, a participant’s report of loss of interest resulted in a 2.7 times increase in the odds of a clinician’s diagnosis of MD compared to no report of this symptom. Further, loss of interest also showed a stronger association with a clinician’s diagnosis than reports of sad mood (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of different self-reported symptoms with a disagreement about depression between the two sources or the clinician’s diagnosis of major depression.

| OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Participant’s report of symptom |

Disagreement between participant and collateral source |

Clinician’s diagnosis of depression |

| Sad mood | 8.82 (0.69–111.91) |

0.75 (0.21–2.71) |

| Anhedonia | 3.78a (1.28–11.19) |

2.72c (1.24–5.97) |

| Low energy | 0.58 (0.16–2.05) |

1.78 (0.54–5.89) |

| Negative thoughts | 0.31b (0.10–0.91) |

1.68 (0.80–3.49) |

| Death wishes | 0.32 (0.04–2.61) |

2.73 (0.68–11.02) |

Notes:

Wald χ2(1) = 5.78, p = 0.02;

Wald χ2(1) = 4.52, p = 0.03;

Wald χ2(1) = 6.2, p = 0.01.

OR, Odds Ratios; CI, Confidence Interval.

Conclusion

Findings from these analyses should be interpreted in the light of certain limitations, some of which we had little control over. Notable among these was that the diagnosis of major depression was established using a semi-structured clinical interview only. It would have been ideal if every study participant could have been interviewed using any of the structured psychiatric diagnostic instruments, possibly like the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.; Sheehan et al., 1998). Hence, it is possible that some cases of MD might have been missed. However, under–diagnosis of MD would only have biased the results such that no significant findings emerged, but these data had sufficient power to pick up a number of significant associations. Next, as required by the NACC, collateral sources had provided information only on the NPI-Q for a majority of the participants. However, the Depression subscale of the NPI-Q is not a robust measure of depression. As a requirement to comply with national guidelines, information on the CollGDS had been collected from only 67 collateral sources. Therefore, even though the CollGDS might have been better suited to examine differences, it is possible that the CollGDS data lacked sufficient power to detect significant associations that might otherwise have been present. We also had no way of controlling for differences in the reliability of information from collateral sources of different participants. Finally, individual symptoms of depression were not assessed using a standard depression rating scale, like the HDRS, but rather interpreted from the questions on the GDS-15. Consequently, information about all the symptoms of depression that are part of the DSM-IV criteria and which the participants could have experienced was not available.

Acknowledging these limitations, certain interesting observations merit further discussion. There were significant differences and poor agreement in the reports of depression between collateral sources and ADC participants with early-to-moderate cognitive impairment. Participants and collateral sources differed on almost all the GDS questions, except about the presence of impairment in memory. This observation is similar to the findings of earlier reports, where investigators have found this disagreement to be associated with either the patients’ level of insight or the participants’ impaired ability to acknowledge depressive symptoms as the severity of dementia increases (Burke et al., 1998; Gilley et al., 1995).

The multivariate regression analyses involving both self- and collateral-source positive screens for depression suggest that the physicians’ diagnosis of MD is significantly more likely to be associated with only the participant’s report of depression. This association is present even when the mean GDS-15 scores points to the fact that the number of symptoms reported by the accompanying collateral sources was significantly greater than reported by the participants themselves. The association of the clinician’s diagnosis with the participant’s report over that provided by the collateral source has important implications, including the possibility that symptoms otherwise present might be missed. Hence, depression meeting the threshold criteria of clinical significance might not be appropriately diagnosed. A clinician’s hesitation in establishing a diagnosis based largely on the collateral source’s reports is understandable, as caregivers might allow extraneous factors, like their own frustrations, to influence their report of symptoms for the cognitively impaired participants whom they accompanied. This hypothesis has, however, not been bourn out by formal research where care giver factors have been found to explain only between 27 and 33% of the variance in patient mood ratings (Moye et al., 1993; Rosenberg, Mielke, & Lyketsos, 2005; Teri & Truax, 1994). Future revisions of criteria should specify that symptoms could count toward a clinical diagnosis, whether patients or their collateral sources report them.

Our report is the only one to examine which symptoms are likely to have a statistically significant association with a disagreement between the two reports of depression. As can be expected, participants and their collateral sources were significantly less likely to disagree when participants had reported any negative cognitive symptoms, like hopelessness, helplessness or worthlessness. Conversely, but much more importantly, their chances of disagreement increased significantly when participants endorsed experiencing loss of interest in pleasurable activities. Although loss of interest has also been similarly implicated by previous reports, our analysis demonstrates that this symptom was one that resulted in a statistically significant increase in the disagreement between the two sources of reports of depression (Mackenzie et al., 1989; Moye et al., 1993).

In a separate multivariate analysis, the same symptom of loss of interest also showed a strong association with a clinician’s diagnosis of MD, which was significantly greater than that seen for the other symptoms of depression in the model. This would suggest that, all other symptoms remaining the same, the same symptom associated with a disagreement between participants and their collateral sources is also the symptom that clinicians used significantly more often to diagnose depression in this population. Also, of interest is the fact that loss of interest demonstrated a stronger association with the diagnosis ofMD than the symptom of sad mood, which is often, considered the hallmark of depression. While the possibility exists that clinicians might have mistaken the syndrome of apathy in dementia with that of depression, we did not find any association of the clinician’s diagnosis of MD with apathy-related symptoms in additional analysis of data not presented in this report (e.g. with GDS Q9: ‘Do you prefer to stay at home, rather than going out and doing new things?’).

There is evidence that geriatric patients with clinically significant depression and without any cognitive impairment might be impaired in their experience and report of sad mood. This observation has lead to a discussion about ‘depression without sadness’ as an alternate presentation of depression in the geriatric population (Gallo, Rabins, & Anthony, 1999). The possibility could exist that something similar is also seen in those with cognitive impairment. A strong association of a motivational symptom, like loss of interest, with a diagnosis of depression has also been recently reported in those with only MCI as well (Kumar, Jorm, Parslow, & Sachdev, 2006). It is likely that depression in those with cognitive impairment is often characterized by a syndrome of ‘motivational’ symptoms rather than symptoms of a predominant change in mood (Jorm, 2001). Findings from our data lend some support to this observation that a symptom like loss of interest may play a greater role in the depression experienced by those with cognitive impairment.

The prevalence of major depression in participants with MCI or AD at our center is remarkably similar to the figure of around 13% using DSM-IV criteria reported by Vilalta-Franch et al. (2006). An advantage of this investigation at our center was the naturalistic manner in which participants were evaluated and the clinicians established a diagnosis of depression. Another highlight was that our investigation examined the association of reports of depression from different sources in comparison to a clinician’s diagnosis of MD. The findings suggest that changes in the ability to experience pleasure, or loss of interest, might be a much more important feature of depression co-occurring in those with AD or MCI than the ability to formulate or express a predominantly sad mood. The implications with regards future revisions of the diagnostic criteria for this condition are underscored. Further research might also attempt to examine the significance of the presence of symptoms of depression other than either loss of interest or sad mood. Such sub-syndromal symptoms have been shown to be important with regards to quality of life in the elderly (Chopra et al., 2005). Appropriate detection of depression with AD or MCI is likely to result in a substantial decrease in the burden from the disease as depression remains an eminently treatable neuropsychiatric symptom associated with dementia.

Acknowledgements

Data presented in this manuscript were collected as part of an Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center grant from the National Institute of Aging, P30 AG19606. Some of the findings in this manuscript were presented at the 2007 Annual Meeting of the American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry (AAGP), March, New Orleans, LA, USA. We would like to thank Dr Thomas Oxman for his constructive criticism and Ms Christine Oots for her help in preparing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Beekly DL, Ramos EM, van Belle G, Deitrich W, Clark AD, Jacka ME, et al. The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) database: An Alzheimer disease database. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2004;18(4):270–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke WJ, Roccaforte WH, Wengel SP, McArthur-Miller D, Folks DG, et al. Disagreement in the reporting of depressive symptoms between patients with dementia of the Alzheimer type and their collateral sources. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1998;6(4):308–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemerinski E, Petracca G, Sabe L, Kremer J, Starkstein SE. The specificity of depressive symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(1):68–72. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra MP, Zubritsky C, Knott K, Have TT, Hadley T, Coyne JC, et al. Importance of subsyndromal symptoms of depression in elderly patients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;13(7):597–606. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.7.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JL. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Assessing psychopathology in dementia patients. Neurology. 1997;48(5 Suppl 6):S10–S16. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.5_suppl_6.10s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JL, McRae T, Zhang R, Donepezil-Sertraline Study G. Effects of donepezil on neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia and severe behavioral disorders. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14(7):605–612. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000221293.91312.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308–2314. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Craen AJ, Heeren TJ, Gussekloo J. Accuracy of the 15-item geriatric depression scale (GDS-15) in a community sample of the oldest old. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2003;18(1):63–66. doi: 10.1002/gps.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkinjuntti T, Ostbye T, Steenhuis R, Hachinski V. The effect of different diagnostic criteria on the prevalence of dementia. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337(23):1667–1674. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712043372306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-mental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo JJ, Rabins PV, Anthony JC. Sadness in older persons: 13-year follow-up of a community sample in Baltimore, Maryland. Psychological Medicine. 1999;29(2):341–350. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798008083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilley DW, Wilson RS, Fleischman DA, Harrison DW. Impact of Alzheimer’s-type dementia and information source on the assessment of depression. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7(1):42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology. Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF. History of depression as a risk factor for dementia: An updated review. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;35(6):776–781. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, Smith V, MacMillan A, Shelley T, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. Journal of Neuropsychiatry & Clinical Neurosciences. 2000;12(2):233–239. doi: 10.1176/jnp.12.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Jorm AF, Parslow RA, Sachdev PS. Depression in mild cognitive impairment in a community sample of individuals 60–64 years old. International Psychogeriatrics. 2006;18(3):471–480. doi: 10.1017/S1041610205003005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie TB, Robiner WN, Knopman DS. Differences between patient and family assessments of depression in Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1989;146(9):1174–1178. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.9.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGivney SA, Mulvihill M, Taylor B. Validating the GDS depression screen in the nursing home. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1994;42(5):490–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb04969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moye J, Robiner WN, Mackenzie TB. Depression in Alzheimer patients: Discrepancies between patient and caregiver reports. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 1993;7(4):187–201. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199307040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olin JT, Katz IR, Meyers BS, Schneider LS, Lebowitz BD. Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression of Alzheimer disease: rationale and background. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002;10(2):129–141. [erratum appears in Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002 May–Jun; 10(3):264] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olin JT, Schneider LS, Katz IR, Meyers BS, Alexopoulos GS, Breitner JC, et al. Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression of Alzheimer disease. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002;10(2):125–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisberg B, Borenstein J, Salob SP, Ferris SH, Franssen E, Georgotas A. Behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: Phenomenology and treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1987;48:9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg PB, Mielke MM, Lyketsos CG. Caregiver assessment of patients’ depression in Alzheimer disease: Longitudinal analysis in a drug treatment study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;13(9):822–826. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.9.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan K, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59 Suppl 20:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale. Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clinical Gerontologist. 1986;5:165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Teri L, Truax P. Assessment of depression in dementia patients: Association of caregiver mood with depression ratings. Gerontologist. 1994;34(2):231–234. doi: 10.1093/geront/34.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilalta-Franch J, Garre-Olmo J, Lopez-Pousa S, Turon-Estrada A, Lozano-Gallego M, Hernandez-Ferrandiz M, et al. Comparison of different clinical diagnostic criteria for depression in Alzheimer disease. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14(7):589–597. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000209396.15788.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson LC, Pignone MP. Screening accuracy for late-life depression in primary care: A systematic review. Journal of Family Practice. 2003;52(12):956–964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L, Wahlund LO, et al. Mild cognitive impairment – beyond controversies, towards a consensus: Report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2004;256(3):240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1982;17(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubenko GS, Zubenko WN, McPherson S, Spoor E, Marin DB, Farlow MR, et al. A collaborative study of the emergence and clinical features of the major depressive syndrome of Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160(5):857–866. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]