Abstract

Background and Objective

To compare the effectiveness of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (PDT), standard endodontic treatment and the combined treatment to eliminate bacterial biofilms present in infected root canals.

Study Design/Materials and Methods

Ten single-rooted freshly extracted human teeth were inoculated with stable bioluminescent Gram-negative bacteria, Proteus mirabilis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa to form 3-day biofilms in prepared root canals. Bioluminescence imaging was used to serially quantify bacterial burdens. PDT employed a conjugate between polyethylenimine and chlorin(e6) as the photosensitizer (PS) and 660-nm diode laser light delivered into the root canal via a 200-µ fiber, and this was compared and combined with standard endodontic treatment using mechanical debridement and antiseptic irrigation.

Results

Endodontic therapy alone reduced bacterial bioluminescence by 90% while PDT alone reduced bioluminescence by 95%. The combination reduced bioluminescence by >98%, and importantly the bacterial regrowth observed 24 hours after treatment was much less for the combination (P<0.0005) than for either single treatment.

Conclusions

Bioluminescence imaging is an efficient way to monitor endodontic therapy. Antimicrobial PDT may have a role to play in optimized endodontic therapy.

Keywords: endodontic therapy, root canal infection, photodynamic therapy, polyethyleneimine chlorin(e6) conjugate, bioluminescence imaging, biofilm

INTRODUCTION

Bacterial infection plays an important role in the development of necrosis in the dental pulp and the formation of periapical lesions, therefore, the main goal of endodontic treatment is the elimination of bacterial infection and associated inflammation in the pulpal tissue and also the mechanical removal of damaged tissue found inside the root canal that acts as a growth medium for microbes [1]. Accepted treatment procedures to eliminate the infection include a combination of chemical cleaning involving irrigation with a disinfectant agent such as sodium hypochlorite or hydrogen peroxide, and mechanical treatment with files that debride the root canal and produce a shaping effect [2], the application of an inter-appointment dressing containing an antimicrobial agent and finally sealing of the root canal [3]. The main causes of treatment failure are the presence of persistent microorganisms and the recontamination of the canal due to inadequate sealing [4,5]. In the case of conventional endodontic treatment failure, retreatment, surgical endodontic treatment or extraction are carried out with the use of antibiotics and antiseptics as adjunctive therapies, but the long-term use of chemical antimicrobial agents, however, can be rendered ineffective by resistance developing in the target organisms [6–8].

The long-term success rate of conventional endodontic treatment depends on several factors, such as the diverse and complex anatomy of the root canal system that comprises small canals additionally to the main canal, which do not allow direct access during the biomechanical preparation because of their positioning and also their diameters. In addition the antimicrobial susceptibility or resistance of the polymorphous microflora [9], which includes anaerobic, facultative anaerobic and aerobic bacteria [10] may determine the outcome. In particularly, the probability of teeth with apical periodontitis to achieve a complete cure after a first treatment or retreatment is only 74–86% [11,12]. In recent years novel antimicrobial approaches to disinfecting root canals have been proposed that include the use of high-power lasers [13] as well as photodynamic therapy (PDT) [14,15]. High power lasers function by dose-dependent heat generation but, in addition to killing bacteria, they have the potential to cause collateral damage such as char dentine, ankylose roots, melt cementum, cause root resorption, and periradicular necrosis [16]. The chief difficulty faced in eliminating bacteria growth in root canals is the fact that they grow as biofilms [17]. A biofilm is a slime layer which naturally develops when bacteria attach to a solid support such as dentine and contains extracellular polysaccharide and other organic material that acts as a natural glue to immobilize the cells [18]. Bacterial biofilms are notoriously difficult to eradicate and show increased resistance to a wide range of antimicrobial compounds [19].

PDT is a new antimicrobial strategy that involves the combination of a non-toxic PS and a harmless visible light source [20]. The excited PS reacts with molecular oxygen to produce highly reactive oxygen species, which induce injury and death of microorganisms [21,22]. It has been established that PS which possess a pronounced cationic charge can rapidly bind and penetrate bacterial cells and therefore these compounds demonstrate a high degree of selectivity for killing microorganisms compared to host mammalian cells [23,24]. PDT has been studied as a promising approach to eradicate oral pathogenic bacteria [25,26] that cause endodontic diseases [27–29], periodontitis [30], peri-implantitis [31] and caries [32]. Some PS, such as toluidine blue and methylene blue have been tested in association with low-intensity red lasers to promote bactericidal effects in vivo [33,34].

Recently, a nondestructive method to study the efficacy of sequential antimicrobial therapy procedures both ex vivo and in vivo has been developed. This method uses real-time optical bioluminescence imaging using sensitive low light cameras to visualize and quantify photon emission from the bioluminescent reporter strain of a bioluminescent bacterium after it has been inoculated [35]. Bioluminescent bacteria have been successfully applied for real-time monitoring of infections [36]. Bioluminescence emission from the infected animal or growth substrate can be correlated with cell counts obtained using homogenization/extraction and conventional culturing methods. The primary advantage of this approach over alternative methods is that it provides real-time quantitative assessment of bacterial burden as opposed to qualitative assessment of bacterial load displaced onto paper points, swabs, extracted from part of the sample or visualized by electron microscopy. Moreover, bioluminescent bacteria can be quantified over sequential procedures without destroying the sample [37]. Our laboratory has employed bioluminescent imaging as a convenient means to monitor the effectiveness of antimicrobial PDT in animal models of infections caused by several bioluminescent pathogens [38]. This methodology has been demonstrated in mouse models of infected wounds [39,40] burns [41] and abscesses [42] using both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.

In the present study we report on endodontic PDT using a recently reported [43] PS consisting of a covalent conjugate between the polycationic polymer polyethylenimine and the PS chlorin(e6) that is highly effective in killing Gram-negative bacteria after illumination with red light. PDT alone, standard endodontic treatment alone and the combination of both treatments were compared on 3-day biofilms formed by two bioluminescent Gram-negative species in root canals of freshly extracted human single-rooted teeth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Root Canals

Ten freshly extracted human single-rooted teeth (upper central incisors and upper canines), with straight canals confirmed by radiographic examination, and extracted for periodontal reasons, were collected and stored in sterile saline until employed in the experiment. The crowns were removed using a diamond disc, and the roots were shortened to a length of approximately 13 mm. The canals were enlarged to an apical size of #30 using Kerr files (Maillefer Instruments SA, Switzerland) and cleaned with 10 ml of 2.5% sodium hypochlorite solution between each endodontic file. The external root surfaces were sealed with two layers of nail polish to avoid environmental contamination. The apical foramen was subsequently closed with composite material (Filtek Z 250, 3M, Brazil). The root canals were irrigated with 17% EDTA for 2 minutes followed by irrigation with PBS solution to remove the smear layer [44]. Prior to inoculation, the specimens were sterilized by autoclaving for 15 minutes at 121°C.

Bacterial Strain and Growth Conditions

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (XEN5) and Proteus mirabilis (XEN44) that had been engineered to be stably bioluminescent by transformation with a transposon containing the entire Photorhabdus luminescens lux operon [45] were a kind gift from Xenogen Corp. (Alameda, CA).

Bacteria were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth at 37°C with shaking (150 rpm) to form a stationary growth phase suspension of 1 × 109 cells/ml. Ten microliters of this suspension was added into each root canal and each tooth was placed inside a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube that was subsequently sealed and kept upright and incubated for 72 hours at 37°C with shaking to allow biofilm formation. After 72 hours bioluminescence imaging of each tooth inside its transparent microcentrifuge tube was carried out with a low-light intensified camera (Hamamatsu Photonics KK, Bridgewater, NJ). The use of this imaging system has been described in detail [39]. Briefly bioluminescence signal was accumulated for 2 minutes at 35 sensitivity level and a maximum setting on the image intensifier control module. Using ARGUS software the luminescence image was presented as a false-color image superimposed on top of the grayscale reference image. The image-processing component of the software gave mean pixel values from the luminescence images on defined areas covering each tooth on a 256-grayscale. For comparisons of bioluminescence images the same bit-range was used for all the images. These images served to confirm the level of infection and to obtain the initial signal from the bacteria inside the root canal.

Photosensitizer (PS)

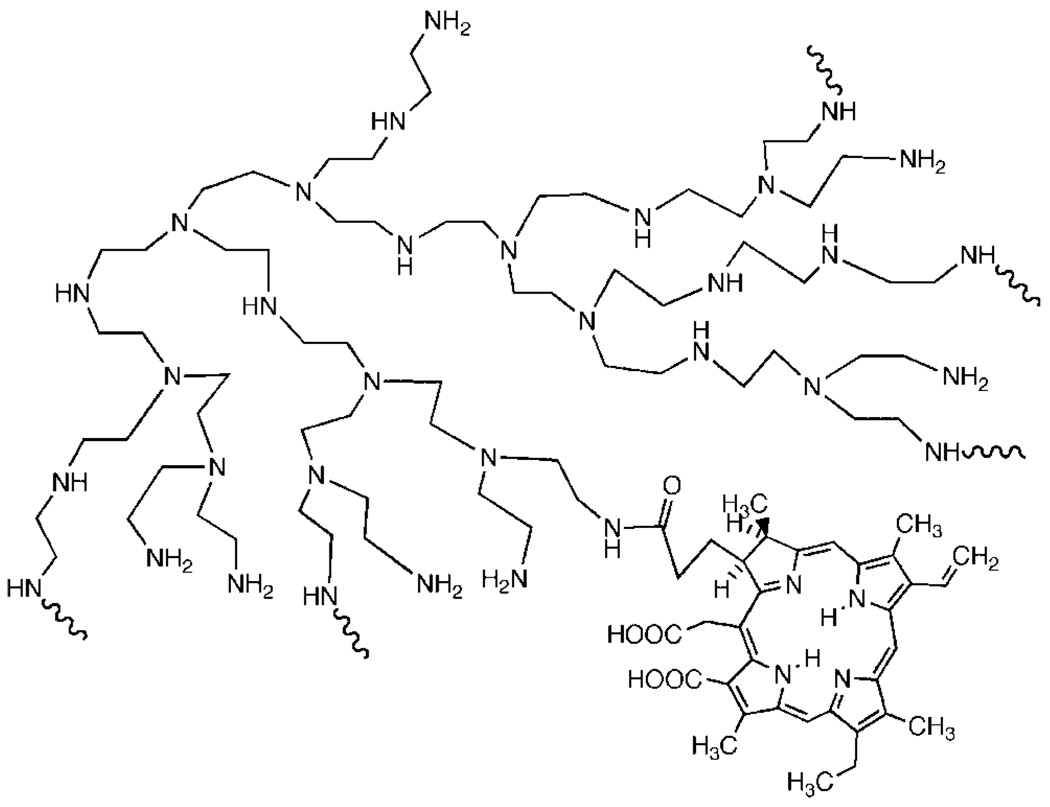

The PS used was a conjugate between polyethylenimine (PEI) and chlorin(e6) and the synthesis and characterization has been previously described in detail [43]. Briefly, high molecular weight branched PEI (MWt = 10,000–25,000, Aldrich Chemical Catalog # 40,872-7, Milwaukee, MI) was reacted with ce6 (Porphyrin Products, Logan, UT) in the presence of 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide hydrochloride (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The conjugate was purified by size exclusion chromatography and characterized by HPLC on a diol column. The conjugate had an average substitution ratio of 1 ce6 per PEI chain and a partial representation of its structural formula is given in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Structural formula of PEI-ce6.

In Vitro Experiments

Suspensions of P. aeruginosa in stationary phase were diluted in PBS to a cell density of 108 per ml, and 1 ml aliquots were added to wells of a 24-well plate and the relative light unit values were read in a luminescence plate-reader (MicroBeta Trilux 1450, PerkinElmer Life And Analytical Sciences, Inc., Wellesley, MA) followed by removal of 10 µl aliquots for serial dilution and streaking on square BHI agar plates for colony forming units (CFUs) enumeration according to the method of Jett et al. [46]. Bacteria were incubated with 10 µM PEI-ce6 for 10 minutes followed by illumination with 660-nm light from a diode laser (MMOptics, São Paulo, Brazil) for defined times corresponding to the delivery of 5, 10, 20, and 40 J/cm2. At each stage the luminescence values and CFUs were measured. Survival fractions were determined from the CFUs in the initial innoculum and compared with the fraction of bioluminescence remaining.

Endodontic PDT

Four different treatments or combinations were performed in the ten root canals and before each treatment all the teeth were sterilized by autoclaving and recontaminated for 72 hours, using the same method described above. The reuse of root canals for infection studies after careful sterilization has been previously reported.54 To perform PDT, any liquid inside the root canal was removed with a pipette and the canals were filled with 10 µl of a 10 µM solution of PEI-ce6 and allowed to incubate for 10 minutes followed by a second bioluminescence imaging to quantify any dark toxicity of the PS. Thereafter, the illumination was performed with a 200-µm diameter fiber-coupled diode laser. The laser delivered 660-nm light at a total power of 40 mW out of the fiber. The fiber was initially placed in the apical portion (bottom) of the root canal and spiral movements, from apical to cervical, were manually performed to ensure even diffusion of the light inside the canal lumen [47]. These movements were repeated approximately ten times per minute and a final bioluminescence image was captured.

Conventional Endodontic Treatment

Conventional endodontic treatment was administered by abrading the interior of the canals using a sequence of three endodontic Kerr files, #30, #35, and #40 (Maillefer Instruments). The canals were irrigated with 10 ml of 2.5% sodium hypochlorite followed by 10 ml of 3% hydrogen peroxide solution between each file using a 28-gauge needle and syringe. To prevent external contamination of the root surface by overflowing irrigant, the teeth were held inverted during the irrigation stage. Bioluminescence imaging was performed once after completion of the procedure.

Combination of Endodontic Treatment and PDT

Endodontic treatment was performed as described above followed by bioluminescence imaging and then PDT was then performed as described with bioluminescence imaging at each stage.

Twenty-four hours regrowth studies

The treated root canals (all groups) after the final image had been captured had any liquid inside the root canals removed and replaced with 10-µl fresh sterile BHI broth. The teeth were then placed inside microcentrifuge tubes as described and returned to the incubator at 37°C for a further 24 hours to evaluate the amount of bacterial regrowth. A group of teeth containing 3-day biofilms were left without any kind of treatment and given 10-µl fresh BHI and returned to the incubator for 24 hours regrowth as a control group.

Statistics

Values are given as means and error bars are standard errors. Statistical comparisons between means were performed with one-way ANOVA using Microsoft Excel.

RESULTS

In Vitro Antimicrobial PDT of Bioluminescent Bacteria

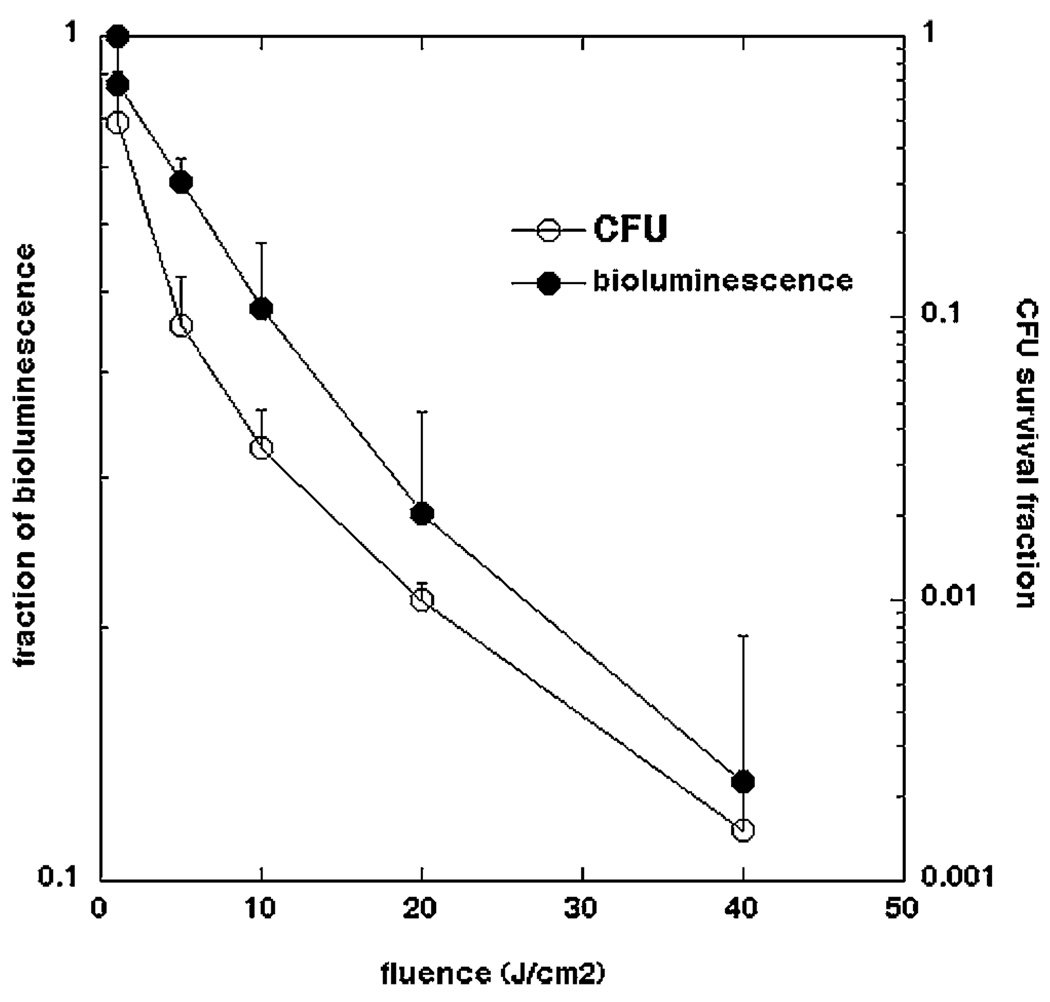

In order to use bioluminescence imaging as a surrogate marker of bacterial burden or bacterial viability it is necessary to be able to correlate the strength of the luminescence signal emitted from the bacterial cells with number of CFU. The loss of viability curves as measured by CFU and by loss of luminescence, as a function of light-dose, for bacteria incubated with 10-µM PEI-ce6 conjugate for 10 minutes are shown in Figure 2. Loss of luminescence showed the same dose-response curve shape as loss of CFU but the absolute reductions were 2 logs less. The reasons for this discrepancy are likely to be twofold. The limits of sensitivity of the luminescence assay with the plate reader is a 3-log reduction in signal, while the CFU assay can measure a 6-log reduction in viability. Secondly it appears that the cytotoxic insult to the bacteria causes loss of viability more readily than loss of luminescence. The mechanism by which luminescence decreases after photodynamic inactivation (PDI) is uncertain, but may be due to exhaustion or loss of the luciferase substrate decanal, the loss of the energy source (reduced flavin mononucleotide) or to photochemical damage to the luciferin enzyme. Nevertheless the data shows that measured reductions in luminescence are likely if anything to underestimate the actual extent of bacterial killing in the root canals.

Fig. 2.

Comparative loss of bacterial viability as measured by survival fraction calculated from CFU on agar plates and by fraction of bioluminescence signal remaining after PDT using 660-nm light of a P. aeruginosa suspension incubated with 10 µM PEI-ce6 for 10 minutes in vitro.

Development of Root-canal Infection Model

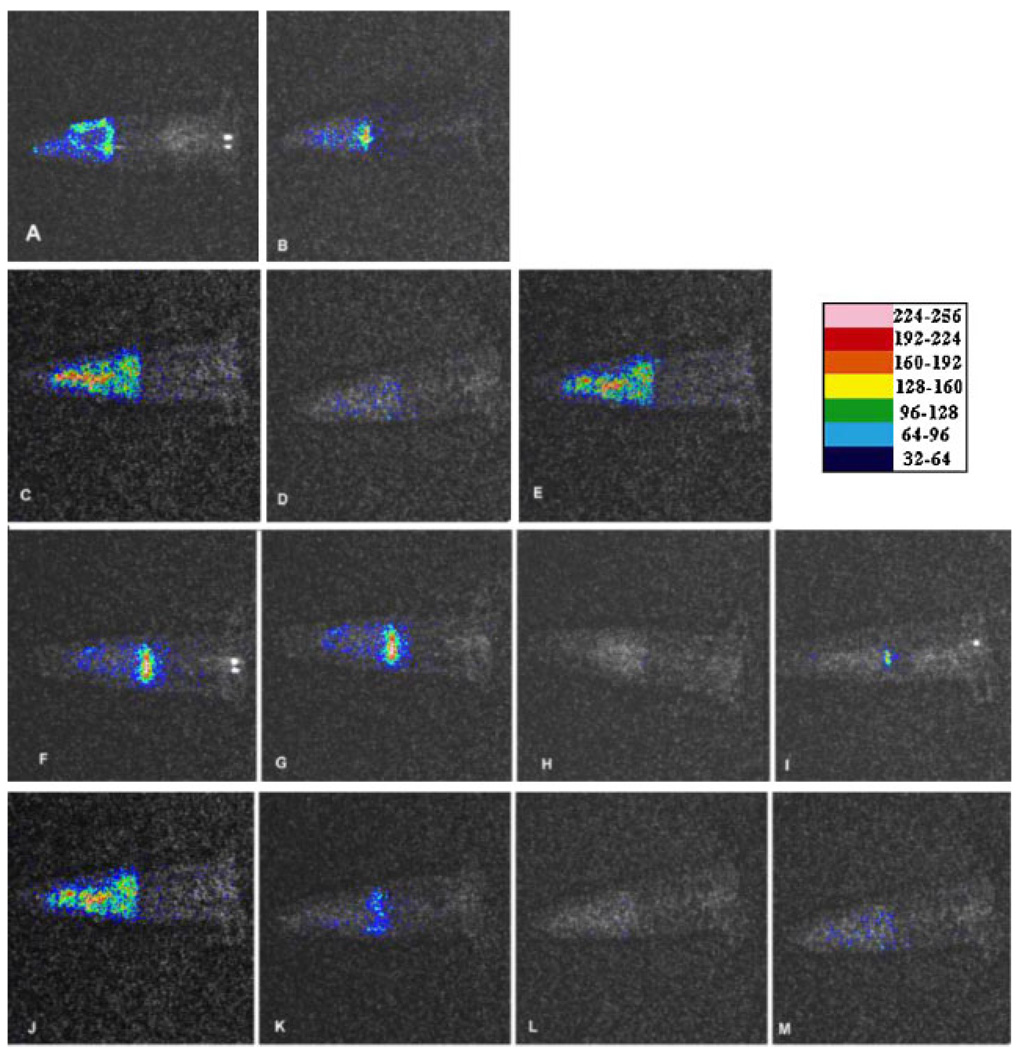

The addition of 10-µl of a suspension containing 108 cells of either P. aeruginosa or P. mirabilis into the root canal followed by 3 days incubation at 37°C reliably and reproducibly produced bioluminescent biofilms that could be imaged through the width of the tooth material. There were minor variations from tooth to tooth in the pattern of the luminescence detected (see panels A, C, F, and J in Figure 3 for examples of P. aeruginosa biofilms), that were probably due to differences in the geometry of the individual root canal systems. The presence of a microbial biofilm rather than planktonic bacteria was demonstrated by the failure of irrigation with saline to significantly diminish the luminescence signal (data not shown). The bioluminescence signals were remarkable similar regardless of whether P. aeruginosa or P. mirabilis was used to form the biofilm. Since the levels of light emission from cell suspensions are also similar for these two species, this implies that the bacterial burdens inside the root canals were similar for these two bacterial species.

Fig. 3.

Representative bioluminescence images captured of teeth infected with 3-day P. aeruginosa biofilms. The teeth received either: no treatment; (A) before, and (B) 24 hours later; conventional endodontic therapy; (C) before, (D) after, and (E) 24 hours later; PDT; (F) before, (G) after PEI-ce6 incubation, (H) after illumination, and (I) 24 hours later; conventional endodontic therapy followed by PDT; (J) before, (K) after conventional endodontic therapy, (L) after PDT, and (M) 24 hours later. [Figure can be viewed in color online via www.interscience.wiley.com.]

Conventional Endodontic Treatment

The overlaid bioluminescence images of a representative tooth infected with P. aeruginosa 3-day biofilm before treatment, after abrasion and disinfection as described in Materials and Methods and after 24 hours regrowth are shown in Figure 3 (panels C–E). Although endodontic therapy reduced the bioluminescence signal by approximately 90% in most teeth, the signal tended to recur strongly after 24 hours regrowth.

Root Canal PDT

Preliminary experiments were carried out by illuminating the inside of the root canal in two teeth incubated with PS as described in Materials and Methods, for periods of 1, 2, 3, and 4 minutes and measuring the bioluminescence signal after each minute of illumination (2.4 J/minute). There was a fluence-dependent reduction in bioluminescence until a fluence of 9.6 J/cm2 (4 minutes) was reached when further light delivery ceased to have a noticeable effect (data not shown) and this fluence was chosen for the PDT experiments. The overlaid bioluminescence images of a representative tooth infected with P. aeruginosa 3-day biofilm before treatment, after 10 minutes incubation with PEI-ce6, after delivery of 9.6 J, 660-nm light and after 24 hours regrowth are shown in Figure 3 (panels F–I). There was only a slight reduction in bioluminescence signal after 10 minutes duration of contact of the PS solution with the bacteria in the root canal biofilm in the absence of light, while after light was delivered the reduction in signal was dramatic. The bioluminescence signal did recur after 24 hours regrowth, and although in the example shown this was less than in the case of endodontic therapy, this was not always the case.

Combination Treatment

We then asked whether the bacterial burden could be further reduced by carrying out root canal PDT after traditional endodontic therapy. The overlaid bioluminescence images of a representative tooth infected with P. aeruginosa 3-day biofilm before treatment, after endodontic therapy, after PDT (PEI-ce6 and 9.6 J, 660-nm light) and after delivery of 9.6 J, 660-nm light are shown in Figure 3 (panels J–M). The endodontic treatment again reduced the bioluminescence by 90% and the PDT that followed reduced the bioluminescence even further. Interestingly (and somewhat unexpectedly) the amount of regrowth seen after 24 hours was much less than that seen with either treatment alone.

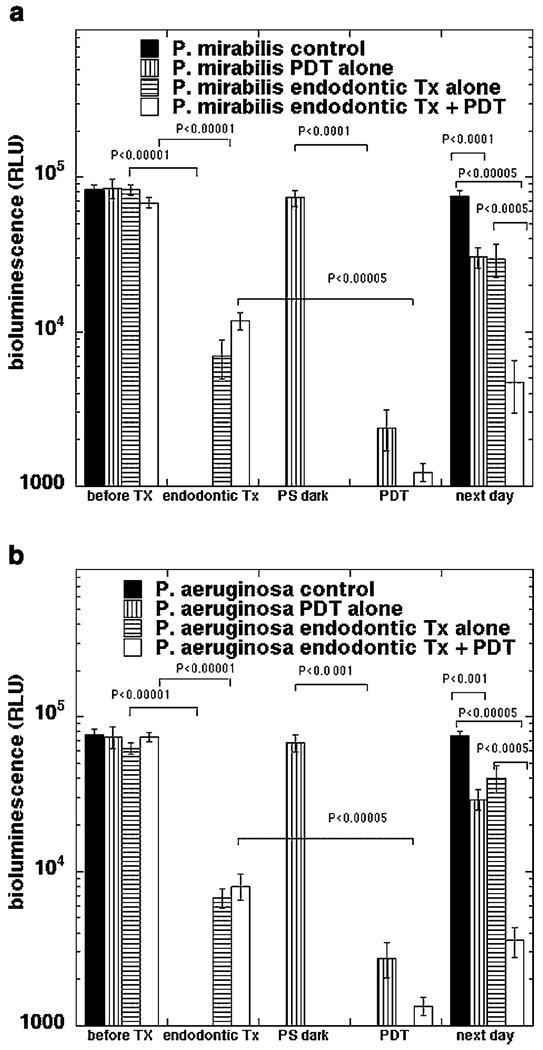

Statistical Comparisons

The mean and SEM values of bioluminescence from ten infected teeth per group subjected to the four treatments are shown in Figure 4A (P. aeruginosa) and B(P. mirabilis). It is remarkable how similar the results were for the two bacterial species. Endodontic treatment alone reduced bioluminescence from both bacteria by >90% (P<0.0001) while PDT alone reduced bioluminescence by >95% (P<0.0001). The combination of treatments reduced bioluminescence by almost 99% (P<0.00001). The p values for comparisons of the various treatments are given in Table 1. For P. mirabilis, PDT was significantly better than endodontic treatment (P = 0.035) but there was no significant difference for P. aeruginosa. The combination was significantly better than endodontic treatment alone (P = 0.0011 for P. mirabilis and P = 0.023 for P. mirabilis) but there was no significant difference compared to PDT alone for either bacterium. After 24 hours of regrowth all the root canals showed some evidence of recontamination. Single treatments showed significantly less regrowth than controls (P = 0.002–0.0001) and PDT was significantly better (P<0.0001) than endodontic treatment in the case of P. aeruginosa. The root canals that received the combination of endodontic treatment and PDT had significantly less contamination after 24 hours compared to control and compared to either single treatment (P<0.0001) for both bacterial species.

Fig. 4.

Bioluminescence signal from teeth after the various treatments described in the text. A: Teeth infected with P. mirabilis; (B) teeth infected with P. aeruginosa. Each point is the mean of values from ten teeth and bars are SEM. Statistical comparisons were carried out by one way ANOVA.

TABLE 1.

P Values for Statistical Comparisons between Mean Bioluminescence Values

| P. aeruginosa | Immediate | After 24 hours |

|---|---|---|

| Endodontic versus control | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| PDT versus control | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| PDT versus endodontic | 0.035 | n.s. |

| Combination versus control | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Combination versus endodontic | 0.0011 | <0.0001 |

| Combination versus PDT | n.s. | <0.0001 |

| P. mirabilis | ||

| Endodontic versus control | <0.0001 | 0.0021 |

| PDT versus control | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| PDT versus endodontic | n.s. | <0.0001 |

| Combination versus control | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Combination versus endodontic | 0.023 | <0.0001 |

| Combination versus PDT | n.s. | <0.0001 |

Performed using one-way ANOVA in Microsoft Excel. n.s., not significant.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to develop a real-time method using bioluminescent bacteria and a low-light imaging camera to evaluate the antimicrobial effects of root canal treatment. Quantitative comparisons were made between the effects of conventional endodontic treatment, root canal PDT or the combination of these treatments on Gram-negative bacterial biofilms and the subsequent regrowth 24 hours later.

P. aeruginosa and P. mirabilis were selected for this investigation based on strong bioluminescence activity and propensity to form biofilms. There are reports of P. mirabilis [48] and P. aeruginosa [49] being isolated as endodontic infectious agents. Their morphology (Gram-negative rods 2–3 µm in length) is highly similar to other Gram-negative rods commonly found in endodontic infections [50]. In addition to the classification of the bacteria, their ability to grow as biofilms seems to be an important determinant of bacterial resistance to antimicrobial therapies as well as endodontic virulence [17]. In this work, the cells were grown for 72 hours to allow biofilm formation, which is expected to increase the difficulty of the antimicrobial challenge to more closely approach real life situations.

Because the bioluminescence imaging method is non-invasive, the comparative evaluation of more than one procedure was possible. Sequential images could be obtained for each tooth and this allows statistical analysis with low amounts of inter-sample variation (Fig. 4A,B). The method provides an alternative to traditional in vitro culture methods using paper point sampling and quantitative culture, and further supports previous reports about the difficulties of completely removing bacteria from root canals. Sedgley et al. [51] developed a bioluminescent model of root canal infection using Pseudomonas fluorescens 5RL which is a strain containing a lux CDABE plasmid that is inducible with salicylate. They determined the correlation between bioluminescent signal and extracted CFUs. This group went on to use this model to study the effect of varying the needle depth during endodontic irrigation [52].

In conventional endodontic treatment of infected root canals, reducing the bacterial count is accomplished by a combination of mechanical instrumentation, various irrigation solutions, and antimicrobial medicaments or dressings placed into the canal. In the present study all the treatments tested were effective in reducing bacterial bioluminescence inside the root canals. PDT alone was more efficient in killing the bacteria than the endodontic treatment alone, although the levels of recontamination or regrowth after 24 hours did not show significant differences between the treatments but both were less than no treatment controls. Our results clearly demonstrated that the combination of both treatments was more effective than either treatment alone in reducing the bacterial bioluminescence signal at the end of the treatment, and more importantly, the combination was very much more effective in reducing the level of bacterial regrowth after 24 hours. The fact that very similar results were obtained with two different bacterial species adds a further level of confidence in the result obtained.

Seal et al. [15] and Lee et al. [14] have reported results using PDT in root canal treatments; both the authors have used phenothiazinium-based PS and low intensity red lasers against Gram-positive bacteria, but did not use an optical fiber to access the root canal lumen. Seal et al. [15] found that 3% sodium hypochlorite irrigation killed more Streptococcus intermedians in the endodontic biofilms than PDT with 100 µg/ml toluidine blue and 21 J of 632-nm laser light.

In conclusion our results suggest that the use of PDT as an adjuvant to the conventional endodontic treatment leads to a statistically significant further reduction of bacterial load (P<0.05) and in particular reduces the amount of bacterial regrowth after 24 hours compared to either treatment alone (P<0.0001). Further studies are required to determine the exact scope of PDT in endodontic therapy, in particular studying more clinically relevant organisms such as Enterococcus faecalis. It should be noted that we have previously shown in vitro that E. faecalis is 100–1,000 times more sensitive to PDT mediated killing compared with Gram-negative species such as P. aeruginosa [53].

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by the NIAID (grant R01 AI050875 to MRH). Aguinaldo S Garcez was supported by a scholarship from CNPq. We thank Xenogen Corp. and Dr. Kevin P Francis for the generous gift of stable bioluminescent bacteria.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siqueira JF., Jr Endodontic infections: Concepts, paradigms, and perspectives. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94(3):281–293. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.126163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bahcall JK, Barss JT. Understanding and evaluating the endodontic file. Gen Dent. 2000;48(6):690–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sedgley C. Root canal irrigation—a historical perspective. J Hist Dent. 2004;52(2):61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ching BB. Common causes of endodontic failure. Hawaii Dent J. 2003;34(4):13–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong R. Conventional endodontic failure and retreatment. Dent Clin North Am. 2004;48(1):265–289. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reynaud Af, Geijersstam AH, Ellington MJ, Warner M, Woodford N, Haapasalo M. Antimicrobial susceptibility and molecular analysis of Enterococcus faecalis originating from endodontic infections in Finland and Lithuania. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2006;21(3):164–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2006.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinheiro ET, Gomes BP, Drucker DB, Zaia AA, Ferraz CC, Souza-Filho FJ. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Enterococcus faecalis isolated from canals of root filled teeth with periapical lesions. Int Endod J. 2004;37(11):756–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2004.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Figdor D. Microbial aetiology of endodontic treatment failure and pathogenic properties of selected species. Aust Endod J. 2004;30(1):11–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.2004.tb00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomes BP, Lilley JD, Drucker DB. Variations in the susceptibilities of components of the endodontic microflora to biomechanical procedures. Int Endod J. 1996;29(4):235–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1996.tb01375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drucker DB, Lilley JD, Tucker D, Gibbs AC. The endodontic microflora revisited. Microbios. 1992;71(288–289):225–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sjogren U, Hagglund B, Sundqvist G, Wing K. Factors affecting the long-term results of endodontic treatment. J Endod. 1990;16(10):498–504. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(07)80180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman S, Mor C. The success of endodontic therapy—healing and functionality. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2004;32(6):493–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bahcall JK, Miserendino L, Walia H, Belardi DW. Scanning electron microscopic comparison of canal preparation with Nd:YAG laser and hand instrumentation: A preliminary study. Gen Dent. 1993;41(1):45–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee MT, Bird PS, Walsh LJ. Photo-activated disinfection of the root canal: A new role for lasers in endodontics. Aust Endod J. 2004;30(3):93–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.2004.tb00417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seal GJ, Ng YL, Spratt D, Bhatti M, Gulabivala K. An in vitro comparison of the bactericidal efficacy of lethal photosensitization or sodium hyphochlorite irrigation on Streptococcus intermedius biofilms in root canals. Int Endod J. 2002;35(3):268–274. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2002.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bahcall J, Howard P, Miserendino L, Walia H. Preliminary investigation of the histological effects of laser endodontic treatment on the periradicular tissues in dogs. J Endodont. 1992;18:47–51. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)81369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Distel JW, Hatton JF, Gillespie MJ. Biofilm formation in medicated root canals. J Endod. 2002;28(10):689–693. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200210000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fux CA, Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Stoodley P. Survival strategies of infectious biofilms. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13(1):34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis K. Riddle of biofilm resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45(4):999–1007. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.999-1007.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamblin MR, Hasan T. Photodynamic therapy: A new antimicrobial approach to infectious disease? Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2004;3(5):436–450. doi: 10.1039/b311900a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Demidova TN, Hamblin MR. Photodynamic therapy targeted to pathogens. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2004;17(3):245–254. doi: 10.1177/039463200401700304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wainwright M. Photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy (PACT) J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42(1):13–28. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soukos NS, Ximenez-Fyvie LA, Hamblin MR, Socransky SS, Hasan T. Targeted antimicrobial photochemotherapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42(10):2595–2601. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.10.2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maisch T, Bosl C, Szeimies RM, Lehn N, Abels C. Photodynamic effects of novel XF porphyrin derivatives on prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(4):1542–1552. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.4.1542-1552.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Komerik N, Macrobert AJ. Photodynamic therapy as an alternative antimicrobial modality for oral infections. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2006;25(1–2):487–504. doi: 10.1615/jenvironpatholtoxicoloncol.v25.i1-2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson M. Lethal photosensitisation of oral bacteria and its potential application in the photodynamic therapy of oral infections. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2004;3(5):412–418. doi: 10.1039/b211266c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonsor SJ, Nichol R, Reid TM, Pearson GJ. Microbiological evaluation of photo-activated disinfection in endodontics (an in vivo study) Br Dent J. 2006;200(6):337–341. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4813371. discussion 329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonsor SJ, Pearson GJ. Current clinical applications of photo-activated disinfection in restorative dentistry. Dent Update. 2006;33(3):143–144. 147–150, 153. doi: 10.12968/denu.2006.33.3.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcez AS, Núñez SC, Lage-Marques JL, Jorge AO, Ribeiro MS. Efficiency of NaOCl and laser-assisted photosensitization on the reduction of Enterococcus faecalis in vitro. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;12(4):e93–e98. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.02.015. (online) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meisel P, Kocher T. Photodynamic therapy for periodontal diseases: State of the art. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2005;79(2):159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2004.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayek RR, Araujo NS, Gioso MA, Ferreira J, Baptista-Sobrinho CA, Yamada AM, Ribeiro MS. Comparative study between the effects of photodynamic therapy and conventional therapy on microbial reduction in ligature-induced peri-implantitis in dogs. J Periodontol. 2005;76(8):1275–1281. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.8.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walsh LJ. The current status of laser applications in dentistry. Aust Dent J. 2003;48(3):146–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2003.tb00025.x. quiz 198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong TW, Wang YY, Sheu HM, Chuang YC. Bactericidal effects of toluidine blue-mediated photodynamic action on Vibrio vulnificus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(3):895–902. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.3.895-902.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Komerik N, Nakanishi H, MacRobert AJ, Henderson B, Speight P, Wilson M. In vivo killing of Porphyromonas gingivalis by toluidine blue-mediated photosensitization in an animal model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(3):932–940. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.3.932-940.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Contag CH, Contag PR, Mullins JI, Spilman SD, Stevenson DK, Benaron DA. Photonic detection of bacterial pathogens in living hosts. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18(4):593–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18040593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burns SM, Joh D, Francis KP, Shortliffe LD, Gruber CA, Contag PR, Contag CH. Revealing the spatiotemporal patterns of bacterial infectious diseases using bioluminescent pathogens and whole body imaging. Contrib Microbiol. 2001;9:71–88. doi: 10.1159/000060392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doyle TC, Burns SM, Contag CH. In vivo bioluminescence imaging for integrated studies of infection. Cell microbiol. 2004;6(4):303–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Demidova TN, Gad F, Zahra T, Francis KP, Hamblin MR. Monitoring photodynamic therapy of localized infections by bioluminescence imaging of genetically engineered bacteria. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2005;81:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamblin MR, O’Donnell DA, Murthy N, Contag CH, Hasan T. Rapid control of wound infections by targeted photodynamic therapy monitored by in vivo bioluminescence imaging. Photochem Photobiol. 2002;75(1):51–57. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2002)075<0051:rcowib>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamblin MR, Zahra T, Contag CH, McManus AT, Hasan T. Optical monitoring and treatment of potentially lethal wound infections in vivo. J Infect Dis. 2003;187(11):1717–1726. doi: 10.1086/375244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lambrechts SA, Demidova TN, Aalders MC, Hasan T, Hamblin MR. Photodynamic therapy for Staphylococcus aureus infected burn wounds in mice. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2005;4(7):503–509. doi: 10.1039/b502125a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gad F, Zahra T, Francis KP, Hasan T, Hamblin MR. Targeted photodynamic therapy of established soft-tissue infections in mice. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2004;3(5):451–458. doi: 10.1039/b311901g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tegos GP, Anbe M, Yang C, Demidova TN, Satti M, Mroz P, Janjua S, Gad F, Hamblin MR. Protease-stable polycationic photosensitizer conjugates between polyethyleneimine and chlorin(e6) for broad-spectrum antimicrobial photoinactivation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50(4):1402–1410. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1402-1410.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haapasalo M, Orstavik D. In vitro infection and disinfection of dentinal tubules. J Dent Res. 1987;66(8):1375–1379. doi: 10.1177/00220345870660081801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maoz A, Mayr R, Bresolin G, Neuhaus K, Francis KP, Scherer S. Sensitive in situ monitoring of a recombinant bioluminescent Yersinia enterocolitica reporter mutant in real time on Camembert cheese. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68(11):5737–5740. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.11.5737-5740.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jett BD, Hatter KL, Huycke MM, Gilmore MS. Simplified agar plate method for quantifying viable bacteria. Biotechniques. 1997;23(4):648–650. doi: 10.2144/97234bm22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gutknecht N, van Gogswaardt D, Conrads G, Apel C, Schubert C, Lampert F. Diode laser radiation and its bactericidal effect in root canal wall dentin. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 2000;18(2):57–60. doi: 10.1089/clm.2000.18.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peciuliene V, Reynaud AH, Balciuniene I, Haapasalo M. Isolation of yeasts and enteric bacteria in root-filled teeth with chronic apical periodontitis. Int Endod J. 2001;34(6):429–434. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2001.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ranta K, Haapasalo M, Ranta H. Monoinfection of root canal with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1988;4(6):269–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1988.tb00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haapasalo M, Ranta H, Ranta KT. Facultative gram-negative enteric rods in persistent periapical infections. Acta Odontol Scand. 1983;41(1):19–22. doi: 10.3109/00016358309162299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sedgley C, Applegate B, Nagel A, Hall D. Real-time imaging and quantification of bioluminescent bacteria in root canals in vitro. J Endod. 2004;30(12):893–898. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000132299.02265.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sedgley CM, Nagel AC, Hall D, Applegate B. Influence of irrigant needle depth in removing bioluminescent bacteria inoculated into instrumented root canals using real-time imaging in vitro. Int Endod J. 2005;38(2):97–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2004.00906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Foley JW, Song X, Demidova TN, Jilal F, Hamblin MR. Synthesis and properties of benzo[a]phenoxazinium chalcogen analogs as novel broad-spectrum antimicrobial photosensitizers. J Med Chem. 2006;49:5291–5299. doi: 10.1021/jm060153i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seal GJ, Ng YL, Spratt D, Bhatti M, Gulabivala K. An in vitro comparison of the bactericidal efficacy of lethal photosensitization or sodium hydrochlorite irrigation on Streptococcus intermedius biofilms in root canals. Int Endod J. 2002;35(3):268–274. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2002.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]