Abstract

Cl-IB-MECA, synthetic A3 adenosine receptor agonist, is a potential anticancer agent. In this study, we have examined the effect of Cl-IB-MECA in a mouse melanoma model. Cl-IB-MECA significantly inhibited tumor growth in immune-competent mice. Notably, the number of tumor-infiltrating NK1.1+ cells and CD8+ T cells was significantly increased in Cl-IB-MECA-treated mice. This effect was correlated with high levels of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interferon γ in melanoma tissue. Depletion of either CD8+ T cells or NK1.1+ cells completely abrogated the antitumor effect of Cl-IB-MECA. Accordingly, Cl-IB-MECA did not affect tumor growth in nude mice. In addition, we also found that the number of mature and active conventional dendritic cells at the tumor site was increased after Cl-IB-MECA administration. Moreover, Cl-IB-MECA significantly increased TNF-α and IL-12p40 release from splenic CD11c+ cells. In conclusion, our study provides novel insights into the mechanism by which Cl-IB-MECA leads to an effective antitumor response that involves the activation of natural killer cells and CD8+ T cells and further highlights its therapeutic potential.

Introduction

Skin melanoma is an aggressive tumor with high metastatic potential and only a 5% 5-year survival rate [1]. The current scientific challenge is to overcome the resistance of melanoma to most chemotherapeutics [2]. Accumulating evidence suggests that the activation of both innate and adaptive immune systems can fight the overproliferation of cancerous cells [3]. However, a major feature of melanoma cells is their ability to escape immune surveillance through multiple mechanisms, such as high production of immunosuppressive factors that can impair immune cell function [4].

The adenosine system has the potential to modulate tumor growth. In particular, adenosine is highly expressed under hypoxic conditions observed in the tumor microenvironment [5]. Adenosine, through binding to the A2A receptor, regulates the overall immune-suppressive activity of immune cells through elevation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate, which facilitates tumor growth [6–11]. Although the role of A2A receptor on immune cells has been well characterized [12], the effects of A3 receptor agonists are far less clear. A3 is an adenosine receptor subtype coupled to Gi/q protein, whose activation leads to the reduction of cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels and phospholipase C (PLC) activation.

It has been reported that A3R agonists (such as IB-MECA and Cl-IB-MECA) are able to inhibit cancer cell proliferation in vitro and in some in vivo tumor models (reviewed in Fishman et al. [13]). Our previous studies report that Cl-IB-MECA can downmodulate the phosphorylation of ERK1/2, induce G0/G1 cell cycle arrest and enhance tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-induced apoptosis in human thyroid cells [14,15]. However, A3R agonists can concomitantly induce granulocyte colony-stimulating factor production through nuclear factor-κB activation, preventing the myelotoxic effects of chemotherapy [13]. Furthermore, oral administration of Cl-IB-MECA enhances the cytotoxic activity of mouse natural killer (NK) cells and increases serum levels of interleukin 12 (IL-12) in a mouse model of melanoma lung metastasis and colon carcinoma [16,17]. Thus, in this study, we have further elucidated the mechanism by which Cl-IB-MECA modulates tumor growth in vivo. More specifically, we have investigated the immunemodulatory effects of Cl-IB-MECA in melanoma-bearing mice.

Here, we demonstrate that Cl-IB-MECA inhibited the tumor growth in an A3R-dependent manner. The systemic administration of Cl-IB-MECA enhanced the presence of dendritic cells (DCs) and NK cells in the tumor microenvironment. We also observed a strong T-cell polarization toward a cytotoxic phenotype that promoted the regression of melanoma lesions. The absence of NK1.1+ cells or CD8+ T cells attenuated Cl-IB-MECA-mediated inhibition of tumor growth. These data suggest that Cl-IB-MECA can positively regulate the induction of the innate and adaptive immunity against melanoma.

Materials and Methods

Cells

B16-F10 murine melanoma cell line was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection-LGC Standards S.r.e. (Milan, Italy) and cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, l-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (10 U/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy).

Mice

Female C57Bl/6J and athymic Nude-Foxn1nu (6–8 weeks old) were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Udine, Italy) and maintained in a pathogen-free animal facility at the “Pascale” National Cancer Institute according to institutional animal care guidelines, Italian DL no. 116 of January 27, 1992, and European Communities Council Directive of November 24, 1986 (86/609/ECC). For tumor challenge, 2 x 105 B16-F10 cells were subcutaneously injected on the right flank of anesthetized mice at day 0. At day 10, mice were intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected with Cl-IB-MECA (CIM, 0.1-1-10 µg/kg; Tocris Cookson Ltd, London, UK) for three consecutive days (day 10-11-12) and were killed on day 13. Tumor growth was monitored by measuring the perpendicular diameters by means of a caliper (Stainless Hardened; Ted Pella, Inc, Redding, CA) and calculated by the formula 4/3π x (long diameter / 2) x (short diameter / 2)2. At the end of each treatment, mice were killed by cervical dislocation, and the tissues were processed further.

In some experiments, MRS1191 (24 µg/kg, i.p.; K i = 31 nM; Sigma-Aldrich) was coadministered with Cl-IB-MECA (1 µg/kg). NK1.1+ or CD8+ T-cell depletion was performed by using functional-grade purified antimouse NK1.1 (PK136; eBioscience, San Diego, CA) [18] or antimouse CD8 (H37-17.2; eBioscience) [18] antibodies, respectively, i.p. injected (100 µg/mouse) every 2 days (days 10 and 12) because these cells have a turnover of 3 to 4 days. In the latter experiments, control mice received the respective control antibody (mouse IgG or rat IgG; eBioscience). The efficacy of depletion was confirmed by flow cytometry analysis. We obtained complete depletion of CD8+ T cells (90%) and 45% reduction of NK1.1+ cells, respectively (data not shown).

Immunohistochemistry

Melanoma tissues were fixed in OCT medium (Ted Pella, Inc). Sections of frozen tumor specimens (7 µm) were fixed with acetone, permeabilized with methanol, and stained either with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E staining) according to standard procedures or further processed for immunofluorescence analysis. Frozen sections were stained with specific antibodies for survivin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, DBA, Milan, Italy) or Ki67 (Dako, Cambridge, UK) and detected with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)- or phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled antimouse secondary antibodies, respectively (eBioscience). In all staining experiments, isotype-matched IgG and omission of the primary antibody was used as negative controls. Apoptotic cells were detected using a kit from BioVision (Mountain View, CA) to visualize DNA breaks as TUNEL+, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Slides were analyzed by using a fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Milan, Italy) by means of Axioplan Imaging Program (Carl Zeiss).

BrdU Labeling

Mice were injected with BrdU (150 µg/mouse, Sigma Aldrich) i.p. 2 hours before sacrifice. Melanoma tissues were then removed, digested, and stained with an FITC-labeled anti-BrdU antibody before FACS analysis.

Flow Cytometry Analysis

Cell suspensions from tumors or spleen or tumor draining lymph nodes (LNs) of treated mice were prepared for flow cytometric analysis 1(FACS). Freshly excised tissues were digested for 30 minutes at 37°C by collagenase A (1 U/ml). Cell suspensions were filtered through a 40-µm nylon strainer, and red blood cells were lysed. Cells were then labeled with the appropriate specific antibodies. Antibodies used were against CD11c-FITC, CD11c-PE, CD11b-PeCy5.5, MHC II-PE, CD80-PE, B220-PE, CD3-PeCy5.5 or PerCp, CD8-PE, and NK1.1-PE (all eBioscience). Apoptotic cells were detected by combined annexin V (AnxV)/propidium iodide (PI) staining using the AnxV-FITC apoptosis detection kit (Bender Medsystem, Vienna, Austria) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The stained cells were analyzed by using Becton Dickinson FACScan flow cytometer.

Isolation of Splenic DCs

CD11c-positive cells were isolated from spleens of naive C57Bl/6J mice by using EasySep-positive selection kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Stem Cell Technologies, Koln, Germany). The purity of the isolated CD11c+ cells was greater than 85% as assessed directly by flow cytometry. CD11c+ cells were seeded and then stimulated for 24 hours with CIM (20 nM–200 nM–2 µM) or vehicle. Levels of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), IL-6, IL-10, IL-12/p40, and IL-23/p19 in the supernatants were assayed by using ELISA kits (R&D System, Abingdon, UK, and eBioscience).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays

Serum and melanoma tissue homogenates levels of interferon γ (IFN-γ), TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p40, and IL-23p40 were analyzed by ELISA kits (R&D Systems and eBioscience).

Analysis of RNA

Total tissue RNA was prepared using RNAspin Mini extraction kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (GE Healthcare, Milan, Italy). Reverse transcription was performed by using first-strand complementary DNA synthesis kit (GE Healthcare) followed by polymerase chain reaction. Thermal cycling conditions were 5 minutes at 95°C, followed by 35 cycles of 45 seconds at 94°C, 20 seconds at 58°C, and 30 seconds at 72°C. Primer pairs of A3R were as follows: forward 5′-GTTCCGTGGTCAGTTTGGAT-3′ and reverse 5′-GCGCAAACAAGAAGAGAACC-3′.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc, La Jolla, CA). Results are expressed asmean ± SEM. All statistical differences were evaluated by either two-tailed Student's t test or one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett post hoc analysis as appropriate. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Cl-IB-MECA Inhibits Melanoma Growth in Mice

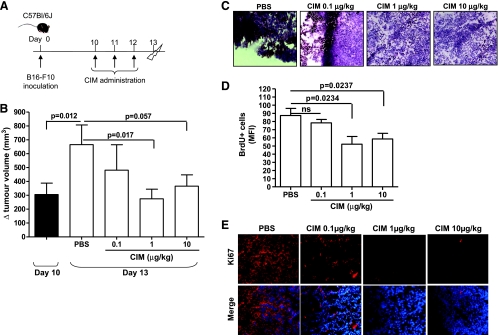

We investigated the antitumor properties of Cl-IB-MECA in a murine melanoma model. C57Bl/6 mice were inoculated subcutaneously onto the back with 2 x 105 B16-F10 cells/mouse at day 0 (Figure 1A). Ten days after cell inoculation, melanoma-bearing mice were treated i.p. with Cl-IB-MECA (CIM, 0.1-1-10 µg/kg) for three consecutive days (days 10, 11, and 12) and then killed at day 13 (Figure 1A). The administration of Cl-IB-MECA did not show any systemic toxic effect in mice, such as drug-related death and body weight loss after CIM administration (data not shown).

Figure 1.

CIM inhibits tumor growth in melanoma-bearing mice. (A) Experimental protocol: 10 days after B16-F10 cell implantation, C57Bl/6 mice were treated (i.p.) with CIM (0.1-1-10 µg/kg) or PBS on days 10, 11, and 12, and mice were killed on day 13. (B) Tumor volume was measured at days 10 and 13 and plotted as volume increase (Δ mm3). At day 10, the tumor volume was 305.4 ± 82.48 mm3. The tumor volume significantly increased between days 10 and 13 in PBS-treated mice. Administration of CIM significantly reduced tumor volume compared with PBS (n = 20). Reduced cell proliferation was observed in CIM-treated mice as determined by representative H&E staining of melanoma tissue-derived cryosections (magnification, x20; C), by reduced numbers of BrdU+ cells (D), and by Ki67 by immunofluorescence staining (magnification, x40; E). ns indicates not significant. Data shown are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett post hoc analysis.

We found that Cl-IB-MECA treatment significantly inhibited tumor growth in a dose-dependent manner compared with PBS-treated mice, reaching a maximum suppression at 1 µg/kg (665.3 ± 142.3 vs 274.8 ± 69.45 Δ (mm3); Figure 1B). Histologic analyses (H&E staining) of the tumor lesions showed that the presence of tumor cells, visible as brown-spotted cells, was reduced when mice were treated with Cl-IB-MECA (1 and 10 µg/kg) compared with PBS (Figure 1C). We examined the proliferative rate of tumor cells by measuring the incorporation of BrdU in vivo. BrdU+ cells were significantly lower in animals treated with both 1 and 10 µg/kg Cl-IB-MECA compared with PBS-treated mice (Figure 1D). Furthermore, the expression of Ki67, a tumor proliferation marker, was also reduced in melanoma tissue in Cl-IB-MECA-treated mice in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1E).

Taken together, these results imply that Cl-IB-MECA can reduce the tumor volume because of the inhibition of cancer cell proliferation. We then asked whether the inhibition of proliferation correlated with apoptosis. The expression of survivin, an antiapoptotic and antiproliferative marker [19], was evaluated in melanoma tissue sections. Treatment with Cl-IB-MECA reduced survivin staining in melanoma cryosections compared with PBS (Figure W1A). The isotype control (mouse IgG) did not show any positive staining. Cl-IB-MECA increased the number of AnxV+/PI+ double-positive cells in melanoma tissue, although not significantly (Figure W1B).

At this regard, we also performed TUNEL assay for signs of apoptosis on melanoma tissue section. In tumor sections harvested from CIM-treated mice, we observed a marked increase in TUNEL+ cells (with green nuclei) compared with control tumor section (Figure W1C). One may therefore conclude that melanoma growth inhibition on Cl-IB-MECA treatment was accomplished by apoptosis.

In addition, we examined whether Cl-IB-MECA (1 nM to 10 µM) could directly affect B16-F10 tumor cells. There was no significant effect of Cl-IB-MECA on cell viability or cell proliferation or apoptosis rate at 24, 48, or 72 hours (Figure W2, A–C). This suggests that the inhibition of tumor growth induced by Cl-IB-MECA in vivo cannot be related to a direct cytotoxic effect on melanoma B16-F10 cells.

Cl-IB-MECA Antitumor Activity Is A3R Dependent

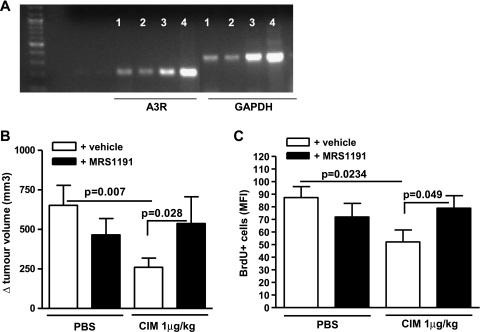

Cl-IB-MECA is a selective A3 adenosine receptor agonist. Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction analysis showed that A3R was expressed in melanoma tissue samples (Figure 2A). Because A3R knockout mice, to our best knowledge, are not commercially available, we used the selective A3R antagonist, MRS1191 (24 µg/kg) [20], administered alone or in combination with Cl-IB-MECA (1 µg/kg). MRS1191 significantly reversed the effect of Cl-IB-MECA on tumor volume regression (Figure 2B, black bar vs open bar). The tumor volume was not significantly altered in control mice treated with MRS1191 alone compared with PBS (Figure 2B, black bar vs open bar). The coadministration of MRS1191 also significantly reversed the Cl-IB-MECA-induced reduction in BrdU+ cells (Figure 2C, black bar vs open bar). These results showed that Cl-IB-MECA-induced inhibition of melanoma growth was A3R dependent.

Figure 2.

The antitumor effect of CIM is reversed by the adenosine A3 receptor antagonist MRS1191. (A) A3R RNA expression on melanoma tissue (lanes 1, 2, 3, and 4 indicate four different samples harvested from melanoma-bearing mice). (B) MRS1191 (24 µg/kg, black bars) was administered by i.p. injection with PBS or CIM 1 µg/kg (n = 10). The effect of CIM on melanoma growth as measured by tumor volume was significantly reversed by MRS1191. (C) MRS1191 significantly reversed the effect of CIM on the number of proliferative (BrdU+) cells (n = 5). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were determined by Student's t test.

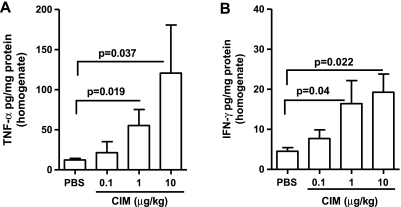

Cl-IB-MECA Increases the Release of TNF-α and IFN-γ in Melanoma Tissues

TNF-α and IFN-γ can induce tumor cell death [21]. We analyzed the levels of TNF-α and IFN-γ in the serum and tumor tissue homogenates harvested from PBS- or Cl-IB-MECA-treated mice. TNF-α levels were significantly increased at 1 and 10 µg/kg of Cl-IB-MECA compared with PBS in tissue homogenates (Figure 3A), whereas no significant changes in serum TNF-α were observed (Figure W3A).

Figure 3.

CIM regulates the production of TNF-α and IFN-γ cytokines. CIM significantly increased the levels of TNF-α (n = 7) (A) and IFN-γ (n = 9) (B) in melanoma tissue homogenates in a dose-dependent manner. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett post hoc analysis.

Cl-IB-MECA administration also induced a significant dose-dependent increase in the levels of IFN-γ in tissue homogenates compared with PBS (Figure 3B). In addition, serum IFN-γ levels were significantly higher in mice treated with 10 µg/kg Cl-IB-MECA (Figure W3B).

In contrast, serum levels of IL-6 and IL-10 were not affected by Cl-IB-MECA treatment (Figure W3, C and D, respectively) and were undetectable in the tissue homogenates.

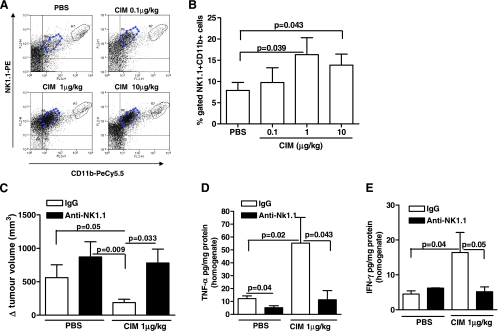

NK Cells Are Essential for Cl-IB-MECA Antitumor Activity

TNF-α and IFN-γ play an important role in both innate and acquired immunity [22] and are released from both NK cells and CD8+ T cells [23–25]. Because Cl-IB-MECA increased both IFN-γ and TNF-α expression in melanoma tissue, we asked whether the antitumor activity of Cl-IB-MECA was related to the activation of the immune system. Cl-IB-MECA treatment significantly increased melanoma-infiltrating NK1.1+ cell numbers in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4, A and B). NK cells were distinguished as CD11b+NK1.1high and CD11b+NK1.1low, as observed in Figure 4A. Furthermore, depletion of NK1.1+ cells completely abrogated the antitumor effect of Cl-IB-MECA (1 µg/kg) (780.6 ± 208.6 vs 872.1 ± 226.1 Δ (mm3); Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Analysis of the role of NK cells on melanoma after CIM administration. CIM significantly increased the number of CD11b+CD11c+ NK1.1+ cells in melanoma tissue compared with PBS (n = 7). Representative plots are shown in A and mean data are depicted graphically in B. (C) Depletion of NK1.1+ cells (black bars) completely blocked the antitumor effect of CIM (1 µg/kg) (n = 7). Depletion of NK1.1 cells (black bars) attenuated CIM induction of TNF-α (D) and IFN-γ (E) levels in melanoma tissue homogenates (n = 7). All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were determined by either two-tailed Student's t testor one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett post hoc analysis as appropriate.

Moreover, a significant reduction in TNF-α and IFN-γ levels was observed in tissue homogenates of Cl-IB-MECA + anti-NK1.1 Ab-treated mice (black bars) when compared with Cl-IB-MECA + IgG (open bars) (Figure 4, D and E, respectively). Taken together, these data demonstrate that NK cells play an important role in the in vivo antitumor activity of Cl-IB-MECA.

Cl-IB-MECA-Treated Mice Have Increased Infiltration of DCs in Melanoma Tissues

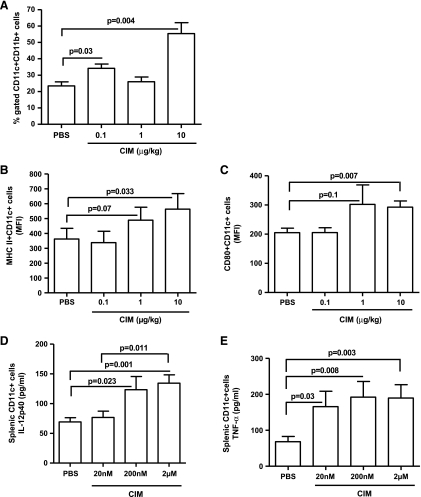

NK cells can affect the development of adaptive immune response [26,27]. Elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines in the tumor microenvironment can also affect the adaptive immune response, including the antigen-presenting capacity of DCs and activation of CD8+ T cells [28,29]. Cl-IB-MECA increased the number of tumorin-filtrating CD11c+CD11b+ myeloid DCs (mDCs) (Figure 5A). Importantly, Cl-IB-MECA enhanced mDC expression of both the MHC class II maturation marker (Figure 5B) and the CD80 activation marker (Figure 5C). These data suggest that melanoma-resident mDCs were mature, active, and able to function as antigen-presenting cells.

Figure 5.

Tumor-infiltrating DCs are mature and active in mice treated with CIM. (A) The number of myeloid DCs (mDCs, CD11c+ CD11b+ cells) significantly increased in melanoma tissue of mice treated with CIM compared with PBS (n = 5). Tumor-infiltrating mDCs were mature and active as indicated by increased expression of the maturation marker MHC class II (B) and activation marker CD80 (C), respectively (n = 5). Splenic CD11c+ cells isolated from naive mice and stimulated with CIM (20 nM-200 nM-2 µM) in vitro for 24 hours released higher amounts of TNF-α (D) and IL-12p40 (E) than PBS-stimulated cells (n = 12). All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett post hoc analysis.

We also assessed the effect of Cl-IB-MECA on DCs. We isolated CD11c+ cells from the spleen of naive mice and treated them with Cl-IB-MECA (20 nM–200 nM–2 µM) for 24 hours. We observed a significant increase in TNF-α and IL-12p40 (Figure 5, D and E, respectively) but not IL-23p19 (data not shown) into the culture supernatants of cells treated with Cl-IB-MECA compared with control.

Cl-IB-MECA antitumor Activity Is Mediated by CD8+ T Cells

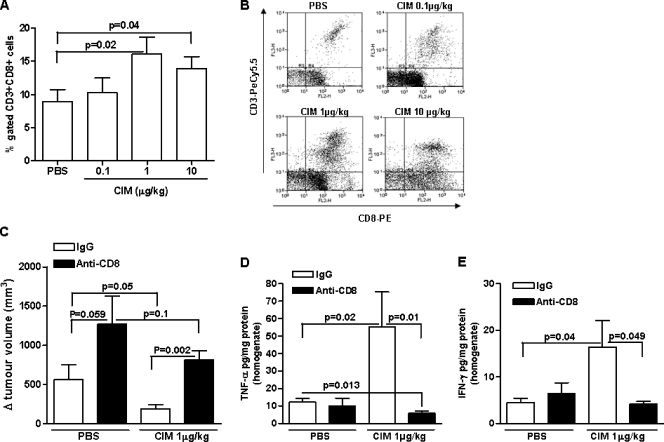

Because DCs can directly regulate CD8+ T cells [30], we next explored whether the antitumor activity of Cl-IB-MECA could be mediated by CD8+ T cells. Cl-IB-MECA induced a dose-dependent increase in the number of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells (Figure 6, A and B). In addition, the antitumor effect of Cl-IB-MECA (1 µg/kg) was significantly attenuated in mice depleted of CD8+ T cells (809.5 ± 118.3 vs 188.5 ± 50.28 Δ (mm3); black bar vs open bar, Figure 6C). Furthermore, depletion of CD8+ T cells also enhanced the tumor volume in PBS-treated mice compared with control IgG-treatedmice (1271 ± 359.5 vs 561.7 ± 191.2 Δ (mm3); black bar vs open bar, Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

The antitumor effect of CIM is mediated by CD8+ T cells. (A) CD3+CD8+ T cells were significantly increased in melanoma tissues of mice treated with CIM compared with PBS (n = 10). (B) Representative FACS plots are shown in the right panel. (C) The antitumor effects of CIM (1 µg/kg) was significantly reversed in CD8+ T-cell-depleted mice (black bar) compared with IgG controls (open bar) (n = 7). Depletion of CD8+ T cells (black bars) significantly reduced CIM-induced TNF-α (D) and IFN-γ (E) expression in melanoma tissue homogenates (n = 7). All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were determined by either two-tailed Student's t test or one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett post hoc analysis as appropriate.

CD8+ T-cell depletion also significantly reduced melanoma tissue levels of TNF-α and IFN-γ in Cl-IB-MECA-treated mice (black bars vs open bars, Figure 6, D and E, respectively).

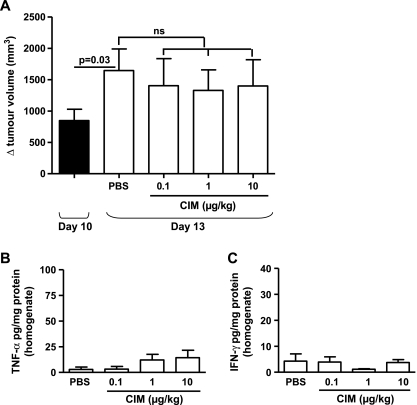

The antitumor ability of Cl-IB-MECA was also completely abrogated in athymic nu/nu (nude) mice (Figure 7A). In addition, melanoma tissue levels of TNF-α and IFN-γ were very low after Cl-IB-MECA administration in nude mice (Figure 7, B and C, respectively).

Figure 7.

Analysis of the antitumor effect of CIM in athymic nude (nu/nu) mice. (A) At day 10, the tumor volume in nude mice was 847.4 ± 180.2 mm3. CIM (0.1-1-10 µk/kg) administration did not affect tumor growth in Nu mice compared with PBS. TNF-α (B) and IFN-γ (C) levels measured in the tissue homogenates harvested from PBS and CIM-treated Nu mice were extremely low. ns indicates not significant. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 10. Statistical differences were determined by Student's t test.

The number of apoptotic cells (AnxV+/PI+ cells) was extremely low in melanoma-bearing nude mice (black bar) compared with the C57Bl/6 mice (open bar) (0.77 ± 0.65 vs 2.73 ± 1.5) and even lower in Cl-IB-MECA-treated nude mice (0.3 ± 0.2), but this was not statistically significant (Figure W4).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the antitumor effect of Cl-IB-MECA. We report that the activation of the immune system is essential for the antitumor activity of Cl-IB-MECA. Specifically, there was an increased recruitment of mature and active mDCs, NK, and CD8+ T cells into melanoma lesions after Cl-IB-MECA treatment. The depletion of NK1.1+ cells or CD8+ T cells completely abrogated the effect of Cl-IB-MECA in melanoma-bearing mice and blocked the production of TNF-α and IFN-γ.

Adenosine is a ubiquitous nucleoside, which has a crucial role in regulating multiple physiological responses, including inflammation [6,31,32]. Adenosine is highly expressed by metabolically stressed cells, such as cancerous cells [5,33]. Within the tumor microenvironment, adenosine interferes with functions of immune cells, protecting tumors from immune-mediated destruction [6,7]. These effects are mediated by the activation of A2A adenosine receptor, which has the highest affinity for adenosine and is also upregulated on effector T cells [11]. In contrast, A3 receptor agonists, such as Cl-IB-MECA, enhance the cytotoxic activity of mouse NK cells and increase serum levels of IL-12 in a mouse model of melanoma lung metastasis and colon carcinoma [16,17]. This suggests that stimulation of the immune system may underlie the antitumor effect of A3 receptor agonists such as Cl-IB-MECA. Future studies using conditional A3R knockout mice will enable confirmation of these results [37]. This approach may also help determine whether the apparent loss of CIM efficacy at 10 µg/kg compared with that observed at 1 µg/kg is due to a loss of A3R selectivity or receptor desensitization.

In our mouse model, Cl-IB-MECA administration significantly inhibited the proliferation of cancerous cells and increased the apoptotic rate in melanoma lesions. Melanoma cells have low levels of spontaneous apoptosis in vivo compared with other tumor cells [2], and our in vitro studies on B16-F10 cells demonstrated that Cl-IB-MECA was unable to directly inhibit cell proliferation or induce apoptosis. It is possible, therefore, that the tumor growth inhibition seen after Cl-IB-MECA administration may be induced by changes in the immune environment leading to melanoma cell death.

IFN-γ can inhibit tumor cell growth and induce the differentiation of NK and T cells into killer cells releasing TNF-α. Splenocytes isolated from melanoma-bearing mice and stimulated ex vivo with Cl-IB-MECA produced high levels of TNF-α compared with PBS (data not shown), suggesting that Cl-IB-MECA may enhance the cytotoxic activity of cells isolated from C57Bl/6 mice with melanoma. Our data show for the first time that CD8+ T cells mediate the antitumor effect of Cl-IB-MECA. The functional relevance of the latter cells in vivo was demonstrated using mice depleted of CD8+ T cells and nude mice in which the activity of Cl-IB-MECA against melanoma was impaired and the production of IFN-γ and TNF-α in the tissue and serum was low.

Consistent with previous studies [16,17], we found that the inhibition of tumor burden after Cl-IB-MECA treatment was correlated with an increased cytotoxic activity of NK cells. In mice depleted of NK1.1+ cells, the antitumor effect of Cl-IB-MECA was reversed and associated with reduced tumor levels of TNF-α and IFN-γ, indicating that both NK and CD8+ T cells are major producers of these cytokines. Further experiments using anti-TNF-α and/or anti-IFN-γ will be necessary to determine whether these cytokines mediate the functional effect of CIM in our tumor model.

Destruction of melanoma requires a complex interaction between cancer cells and immunocompetent cells, including DCs and T cells as well as cells of the innate immune system. DCs are usually immature in the tumor microenvironment because the low expression of MHC class II and/or CD80/86 and IL-12 [34]. Immature DCs limit T-cell activation and thus facilitate tumor progression [34]. In this study, we showed that Cl-IB-MECA increased the number of mature and active DCs in melanoma lesions. Isolated splenic CD11c+ cells stimulated ex vivo with Cl-IB-MECA produced high levels of IL-12 and TNF-α. However, activation of DCs is also mediated by tissue-derived environmental factors and a variety of cells such as NK and T cells [35,36].

In this respect, further in vitro studies will be needed to determine whether the effect of Cl-IB-MECA is a direct effect on DCs or subsequent to actions on NK or CD8+ T cells. The use of conditional A3R knockouts will also enable further clarification of this issue [37]. In addition, extensive pharmacological and genetic studies will also be required to elucidate the mediator(s) responsible for recruitment of these various cells to the tumor in vivo.

In conclusion, our findings are the first demonstration that the A3 adenosine receptor agonist, Cl-IB-MECA, induces an efficient antitumor immune response in melanoma-bearing mice. These results further highlight the therapeutic potential of Cl-IB-MECA in cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the technical assistance provided by G. Forte, E. Bonavita, A. Mautone, L. Curcillo, and M.G. Giordano.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from FARB University of Salerno (in favor of A.P.) and from The Royal Society (in favor of I.M.A. and S.M.). The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

This article refers to supplementary materials, which are designated by Figures W1 to W4 and are available online at www.neoplasia.com.

References

- 1.Cummins CL, Cummins JM, Pantle H, Silverman MA, Leonard AL, Chanmugam A. Cutaneous malignant melanoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:500–507. doi: 10.4065/81.4.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soengas MS, Lowe SW. Apoptosis and melanoma chemoresistance. Oncogene. 2003;22:3138–3152. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirwood JM, Moschos S, Wang W. Strategies for the development of more effective adjuvant therapy of melanoma: current and future explorations of antibodies, cytokines, vaccines and combinations. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2331s–2336s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drake CG, Jaffee E, Pardoll DM. Mechanisms of immune evasion by tumours. Adv Immunol. 2006;90:51–81. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)90002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blay J, White TD, Hoskin DW. The extracellular fluid of solid carcinomas contains immunosuppressive concentrations of adenosine. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2602–2605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohta A, Sitkovsky M. Role of G-protein-coupled adenosine receptors in downregulation of inflammation and protection from tissue damage. Nature. 2001;414:916–920. doi: 10.1038/414916a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohta A, Gorelik E, Prasad SJ, Ronchese F, Lukashev D, Wong MKK, Huang X, Caldwell S, Liu K, Smith P, et al. A2A adenosine receptor protects tumours from antitumour T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13132–13137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605251103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panther E, Corinti S, Idzko M, Herouy Y, Napp M, la Sala A, Girolomoni G, Norgauer J. Adenosine affects expression of membrane molecule, cytokine and chemokine release, and the T-cell stimulatory capacity of human dendritic cells. Blood. 2003;101:3985–3990. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sitkovsky M, Ohta A. The “danger” sensors that STOP the immune response: the A2 adenosine receptors? Trends Immunol. 2005;26:299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raskovolova T, Lokshin A, Huang X, Su Y, Mandic M, Zarour HM, Jackoson EK, Gorelik E. Inhibition of cytokine production and cytotoxic activity oh human antimelanoma specific CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocytes by adenosine-protein kinase A type I signalling. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5949–5956. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zarek PE, Huang CT, Lutz ER, Kowalski J, Horton MR, Linden J, Drake CG, Powell JD. A2A receptor signalling promotes peripheral tolerance by inducing T-cell anergy and the generation of adaptive regulatory T cells. Blood. 2008;111:251–259. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-081646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haskó G, Linden J, Cronstein B, Pacher P. Adenosine receptors: therapeutic aspects for inflammatory and immune diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(9):759–770. doi: 10.1038/nrd2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fishman P, Bar-Yehuda MS, Synowitz M, Powell JP, Klotz KN, Gessi S, Borea PA. Adenosine receptors and cancer. In: Wilson CN, Mustafa SJ, editors. Adenosine Receptors in Health and Disease. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Germany: Springer-Verlag, Berlin; 2009. pp. 399–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morello S, Petrella A, Festa M, Popolo A, Monaco M, Vuttariello E, Chiappetta G, Parente L, Pinto A. Cl-IB-MECA inhibits human thyroid cancer cell proliferation independently of A3 adenosine receptor activation. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:278–284. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.2.5301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morello S, Sorrentino R, Porta A, Forte G, Popolo A, Petrella A, Pinto A. Cl-IB-MECA enhances TRAIL-induced apoptosis via the modulation of NF-κB signalling pathway in thyroid cancer cells. J Cell Physiol. 2009;221:378–386. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harish A, Hohana G, Fishman P, Arnon O, Bar-Yehuda S. A3 adenosine receptor agonist potentiates natural killer cell activity. Int J Oncol. 2003;23:1245–1249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohana G, Bar-Yehuda S, Arich A, Madi L, Dreznick Z, Silberman D, Slosman G, Volfsson-Rath L, Fishman P. Inhibition of primary colon carcinoma growth and liver metastasis by the A3 adenosine receptor agonist CF101. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1552–1558. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scholtes P, Lehr H, Birkenbach M, Blumberg RS, Finotto S. Immunosurveillance of lung melanoma metastasis in EBI-3-deficient mice mediated by CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2009;181:6148–6157. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mita AC, Mita MM, Nawrocki ST, Giles FJ. Survivin: key regulator of mitosis and apoptosis and novel target for cancer therapeutics. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5000–5005. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao TC, Kukreja RC. Late preconditioning elicited by activation of adenosine A (3) receptor in heart: role of NF-κB, iNOS and mitochondrial K (ATP) channel. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34(3):263–277. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suk K, Chang I, Kim YH, Kim S, Kim JY, Kim H, Lee MS. Interferon gamma (IFNγ) and tumor necrosis factor α synergism in ME-180 cervical cancer cell apoptosis and necrosis. IFNγ inhibits cytoprotective NF-κB through STAT1/IRF-1 pathways. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13153–13159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunn GP, Koebel CM, Schreiber RD. Interferons, immunity and cancer immunoediting. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:836–848. doi: 10.1038/nri1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loza MJ, Zamai L, Azzoni L, Rosati E, Perussia B. Expression of type 1 (interferon γ) and type 2 (interleukin-13, interleukin-5) cytokines at distinct stages of natural killer cell differentiation from progenitor cells. Blood. 2002;99:1273–1281. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.4.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neurath MF, Finotto S, Glimcher IH. The role of TH1/TH2 polarization in mucosal immunity. Nat Med. 2002;8:567–573. doi: 10.1038/nm0602-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szabo SJ, Sullivan BM, Stemmann C, Satoskar AR, Sleckman BP, Glimcher LH. Distinct effects on T-bet in TH1 lineage commitment and IFN-γ production in CD4 and CD8 T cells. Science. 2002;295:338–342. doi: 10.1126/science.1065543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palucka K, Banchereau J. Linking innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Med. 1999;5:868–870. doi: 10.1038/11303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu D, Gu P, Pan PY, Li Q, Sato AI, Chen SH. NK and CD8+ T cell-mediated eradication of poorly immunogenic B16-F10 melanoma by the combined action of IL-12 gene therapy and 4-1BB costimulation. Int J Cancer. 2004;109:499–506. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mellman I, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells: specialized and regulated antigen processing machines. Cell. 2001;106:255–258. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00449-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solana R, Casado JG, Delgado E, DelaRosa O, Marín J, Durán E, Pawelec G, Tarazona R. Lymphocyte activation in response to melanoma: interaction of NK-associated receptors and their ligands. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56:101–109. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0141-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burnstock G. The past, present and future of purine nucleotides as signalling molecules. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1127–1139. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klinger M, Freissmuth M, Nanoff C. Adenosine receptors: G protein-mediated signalling and the role of accessory proteins. Cell Signal. 2002;14:99–108. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00235-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lukashev D, Ohta A, Sitovsky M. Hypoxia-dependent anti-inflammatory pathways in protection of cancerous tissues. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:273–279. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.El Marsafy S, Bagot M, Bensussan A, Mauviel A. Dendritic cells in the skin—potential use for melanoma treatment. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2008;22:30–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2008.00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayday A, Tigelaar R. Immunoregulation in the tissues by γδ T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:233–242. doi: 10.1038/nri1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reis e Sousa C. Activation of dendritic cells: translating innate into adaptive immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16:21–25. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salvatore CA, Tilley SL, Latour AM, Fletcher DS, Koller BH, Jacobson MA. Disruption of the A(3) adenosine receptor gene in mice and its effect on stimulated inflammatory cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(6):4429–4434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.