Abstract

Background. Detailed descriptions of long-term persistence of human papillomavirus (HPV) in the absence of cervical precancer are lacking.

Methods. In a large, population-based natural study conducted in Guanacaste, Costa Rica, we studied a subset of 810 initially HPV-positive women with ≥3 years of active follow-up with ≥3 screening visits who had no future evidence of cervical precancer. Cervical specimens were tested for >40 HPV genotypes using a MY09/11 L1-targeted polymerase chain reaction method.

Results. Seventy-two prevalently-detected HPV infections (5%) in 58 women (7%) persisted until the end of the follow-up period (median duration of follow-up, 7 years) without evidence of cervical precancer. At enrollment, women with long-term persistence were more likely to have multiple prevalently-detected HPV infections (P <.001) than were women who cleared their baseline HPV infections during follow-up. In a logistic regression model, women with long-term persistence were more likely than women who cleared infections to have another newly-detected HPV infection detectable at ≥3 visits (odds ratio, 2.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.2–5.6).

Conclusions. Women with long-term persistence of HPV infection appear to be generally more susceptible to other HPV infections, especially longer-lasting infections, than are women who cleared their HPV infections.

INTRODUCTION

Although virtually all cervical cancer and its immediate precursor lesions are caused by persistent high-risk (HR)-human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, the converse is not true: not all persistent HR-HPV infections produce cervical precancer, and only the minority of presumably larger precancers ever invades [1]. When HPV infections were recognized in cervical screening only by their cytopathic (the mildly abnormal Pap smear) or histopathologic (mild dysplasia or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1) correlates, the dogma was that roughly one-half of all infections cleared and that one-fifth to one-third of infections persisted without progression to high-grade disease [2, 3, 4]. These fractions have proven to be qualitatively wrong and were based on a lack of knowledge about sequential, separate HPV infections (practically indistinguishable microscopically or on visual examination) that were acquired and cleared rapidly. Importantly, most HPV infections clear or become undetectable within a year or two [5, 6, 7, 8]. With the introduction of HPV detection into cervical cancer screening, increasing numbers of women will be identified with molecularly detected HPV infection, some with persistent HPV infection—a subset of which will not have overtly detectable, clinically relevant disease. Quantifying and describing the frequency and nature of HPV persistence, by HPV type, will be important to understanding its clinical significance and impact on clinical practice and management. Here, we investigated in more epidemiologic detail the occurrence of long-term viral persistence (LTP) in the absence of apparent cervical precancer and cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

This population-based cohort study, the Proyecto Epidemiologico Guanacaste (PEG), included participants from Guanacaste, Costa Rica, enrolled during the period from June 1993 through December 1994 with the approval of US National Cancer Institute and Costa Rican institutional review boards [6, 9, 10]. Detailed methods of cohort recruitment, screening, and follow-up have been published elsewhere [9, 10].

As previously described [9], a subcohort of sexually active women (2624 [30.7%] of 8545) (We previously reported 2,626 for this sub-cohort but later found that 2 women had undergone hysterectomies and therefore were not at risk of cervical cancer) and 410 virgins were actively observed to explore risk factors for incident cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or more severe (CIN2+). This analytic sub-cohort represented a mixture of higher-risk women (based on enrollment screening results and sexual behavior) and was supplemented by a random sample of the remaining, lower-risk cohort population.

Women in this actively followed subcohort were initially observed annually, except for the 492 women with cytologic low-grade intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) or histologic CIN1 at enrollment, who were observed at 6-month intervals for increased safety of the participants. Women not included in the active subcohort were seen at least once for an exit visit 5-7 years after enrollment. Women who reported themselves as virginal at enrollment were screened every 6 months after they reported becoming sexually active.

Throughout the study, women with cytologic, visual, or Cervigram evidence of high-grade cervical neoplasia underwent colposcopy. At the time of study exit (in most women, 5-7 years after enrollment), to insure the safety of women leaving the cohort, we referred women to colposcopy for the following reasons: (1) abnormal (atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance or LSIL) cytologic interpretation; (2) a positive Cervigram result during either of the past 2 screening visits; or (3) persistent HR-HPV infection or infection with HPV-16 or HPV-18 at either of the 2 most recent screening visits. Finally, a 6.25% random sample of all women in the cohort was referred for an exit colposcopy.

Specimen Collection

Two exfoliative cervical specimens were obtained during a single pelvic examination at baseline and all follow-up visits, as described elsewhere [9, 10]. In brief, the first specimen was used to make a conventional Papanicolaou smear and was then residual specimen was placed in PreservCyt (Hologic) for production of thin-layer cytology slides. A second cervical specimen was collected and stored in specimen transport medium (STM; Qiagen).

HPV DNA Testing

The MY09/M11 L1 degenerate primer polymerase chain reaction (MY09/11 PCR) method used to test STM specimens for HPV genotypes has been described elsewhere [11]. Dot blot hybridization using HPV genotype-specific oligonucleotide probes was used to identify >40 individual HPV genotypes [11]. HPV genotypes 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68 were considered to be the primary HR-HPV genotypes [12], and all others were considered noncarcinogenic. HPV genotypes were also grouped according to phylogenetic species [13].

Pathology

All women with possible high-grade cervical neoplasia at any time, detected by any screening technique (including nurse concern on gross examination) were referred to undergo colposcopy and censored from further follow-up. Any women who received a diagnosis of CIN2+ were treated by loop electrosurgical excision procedure or by inpatient surgery, as clinically indicated. Histology slides were reviewed by one pathologist in the United States (M.E.S.), and if the assessment was discrepant with the Costa Rican reading, a second US pathologist (D.S.) reviewed the case. Only a few very difficult cases with discrepant diagnoses from all 3 pathologists were adjudicated by joint review, occasionally with consideration of cytologic slides as well as histology slides.

Statistical Methods

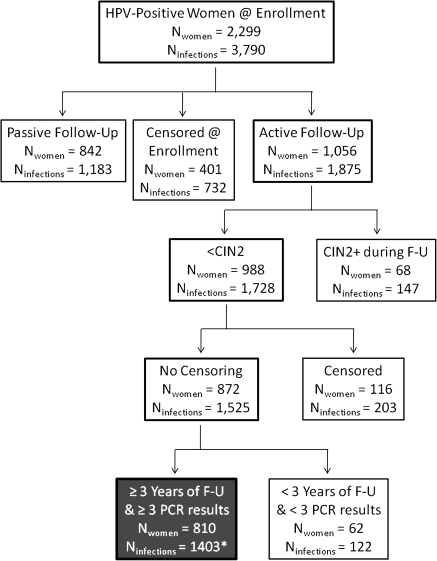

Analyses were conducted 2 ways: with the individual HPV infections and then with the women as the analytic units. We restricted to our analysis the 2299 women who tested HPV positive at baseline, limiting the study further to the 1056 HPV-positive women in the active cohort (ie, the intersection of active follow-up cohort and the cohort of HPV-positive women) (Figure 1). We excluded women in passive follow-up, with only an enrollment and exit visit, because the natural history of their HPV infections was largely unobserved, and therefore, the viral outcomes of the infection could not be classified. We then excluded women who ever had CIN2+ diagnosis during the study.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram to outline which women were included in the analyses of long-term human papillomavirus (HPV) persistence, starting with the subgroup of women who tested HPV positive at baseline by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) regardless of their follow-up, compared with the 2624 women who were undergoing active follow-up). The box at the bottom with gray background and white type highlights the final analytic group. *Includes 29 infections among 18 women with <3 years of follow-up who cleared infection.

Infections were classified as LTP without CIN2+ if (1) the same HPV genotype was detected at enrollment and the exit visit from the study or last visit with a valid PCR result that occurred ≥3 years after enrollment, (2) there were ≥3 positive tests for that HPV genotype, and (3) there were no consecutive negative results during follow-up. That is, a single intermittent negative result between 2 positive results for a HPV genotype was treated as a false-negative result and was recoded as a positive result. Infections were classified as cleared if there were consecutive (≥2) visits at which the HPV genotype was not detected and the HPV genotype was never subsequently detected; in this category, we included 18 women with 29 infections for whom we did not have 3 years of follow-up data (median duration, 2.4 years) but whose infections apparently had cleared by this definition. Other infections (n = 97) not meeting these criteria (eg, intermittent infections—that is, those infections that appeared to clear and that then reappeared) were excluded from this analysis because we were uncertain of how to classify the infections.

The likelihood of developing LTP without CIN2+ was estimated for individual HPV genotypes and for groups of HPV genotypes defined by cancer risk (carcinogenic vs. non-carcinogenic) and phylogenetic species. Binomial 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated.

We also assigned women to hierarchical categories based on the viral outcome (LTP or cleared) to describe factors associated with those outcomes. Differences across categories and continuous variables were tested for statistical significance using Pearson χ2 and Kruskal-Wallis tests, respectively.

To model factors related to LTP using conditional logistic regression, we matched each woman with ≥1 long-term persistent HPV infection with any women who cleared all infections on the basis of the following 2 criteria: the number of enrollment HPV genotypes and the age at enrollment ± 5 years. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were calculated as measures of association. In model 1, we included as a covariate the number of additional, newly detected HPV infections of any duration in follow-up. In model 2, we included as a covariate only those newly detected HPV infections in follow-up that were more overtly enduring: those detectable in ≥3 cervical specimens collected at visits that spanned ≥1 year (n.b., similar to our requirements for defining LTP for testing positive at ≥3 visits). In addition, models were adjusted for the following nuisance variables: enrollment age, number of visits, and the number of new sexual partners during follow-up.

We also searched our data post-hoc for examples of newly detected HPV infections that endured for ≥3 years without CIN2+ and lasted until the end of the study. We required that women were negative for a HPV genotype with ≥2 tests before a newly detected infection could be considered new, or the infection occurred in women who enter the cohort as self-reported virgins and later became sexually active.

Linux SAS software, version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute), and Stata software, versions 8.2 and 9.0 (StataCorp), were used for these analyses. All statistical tests were 2-sided, and P values <.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

By our definitions of viral outcomes among women with no overt cervical disease, 810 women contributed 1403 prevalently detected HPV infections to this analysis. These women had a mean duration of follow-up of 6.7 years (median, 7.0 years; interquartile range, 7.0-7.1 years). We excluded 74 women (9%) with 97 HPV infections (7%) with ambiguous patterns (ie, patterns that could not be classified as having a certain persistent or transient infection[s]). Fifty-eight (7%) of 810 women had 72 LTP HPV infections without CIN2+ (5% of 1403), and 678 (84%) of 810 women had 1234 HPV infections (88% of 1403) that cleared. Women with single and multiple infections detected at baseline did not differ in their likelihood of having LTP (P =.7). Women classified with LTP were observed to have infection for a mean duration of 6.5 years (median, 7.0 years; range, 3.5-7.2 years) until their follow-up period ended.

At baseline, women with LTP were significantly older (mean age, 56.4 years; median age, 58.5 years [range, 46-68 years]) than those who cleared infection (mean age, 35.8; median age, 32.0 years [interquartile range, 25-43 years; P < .001) (Table 1). Despite their older age, women with LTP were more likely to have multiple infections at baseline (63.8% vs 41.3%; P = .001) than were women who cleared their infections.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Women Whose Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infections Cleared versus Those Whose HPV Infections Persisted

| Clearance |

Persistence |

|||||

| Enrollment | (n = 678) | (n = 58) | P | |||

| Smoking | ||||||

| Never | 603 | (88.9) | 46 | (79.3) | .002 | |

| Former | 26 | (3.8) | 9 | (15.5) | ||

| Current | 49 | (7.2) | 3 | (5.2) | ||

| Oral contraceptive use | ||||||

| Missing | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | <.001 | |

| Never | 214 | (31.6) | 38 | (65.5) | ||

| Former | 299 | (44.1) | 16 | (27.6) | ||

| Current | 164 | (24.2) | 4 | (6.9) | ||

| Parity | ||||||

| 0-1 | 67 | (9.9) | 4 | (6.9) | <.001 | |

| 2 | 265 | (39.1) | 10 | (17.2) | ||

| 3-5 | 173 | (25.5) | 7 | (12.1) | ||

| ≥6 | 173 | (25.5) | 37 | (63.8)) | ||

| Age at first sexual experience | ||||||

| <16 | 165 | (24.3) | 16 | (27.6) | .5 | |

| 16 | 91 | (13.4) | 5 | (8.6) | ||

| 17-18 | 212 | (31.3) | 15 | (25.9) | ||

| ≥19 | 210 | (31.0) | 22 | (37.9) | ||

| Lifetime no. of sex partners | ||||||

| 1 | 238 | (35.1) | 26 | (44.8) | .007 | |

| 2-3 | 266 | (39.2) | 27 | (46.6) | ||

| ≥4 | 174 | (25.7) | 5 | (8.6) | ||

| Recent no. of sex partners | ||||||

| 0-1 | 635 | (93.7) | 56 | (96.6) | .6 | |

| ≥2 | 43 | (6.3) | 2 | (3.4) | ||

| Income, Colones | ||||||

| Missing | 31 | (4.6) | 8 | (13.8) | <.001 | |

| <15,000 | 152 | (22.4) | 26 | (44.8) | ||

| 15,000 to <25,000 | 187 | (27.6) | 9 | (15.5) | ||

| 25,000 to <35,000 | 133 | (19.6) | 5 | (8.6) | ||

| ≥35,000 | 175 | (25.8) | 10 | (17.2) | ||

| Marital status at baseline | ||||||

| Married or living together | 476 | (70.2) | 36 | (62.1) | .2 | |

| Divorced, separated, widowed, or single | 202 | (29.8) | 22 | (37.9) | ||

| HPV infections at baseline | ||||||

| Single | 398 | (58.7) | 21 | (36.2) | .001 | |

| Multiple | 280 | (41.3) | 37 | (63.8) | ||

NOTE. Data are no. (%) of subjects, unless otherwise indicated. Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to test for differences between viral outcomes for continuous variables, Fisher's exact tests were used for two category variables, and Pearson's chi-square for were used for three or more category variables.

Women with LTP were observed for a slightly shorter duration than were women who cleared their infections (P =.04), but there were no significant differences in the number of follow-up visits (P =.2). There were no significant differences in the number of self-reported new sexual partners (P =.9) or number of new HPV infections detected during follow-up (P =.5) by viral outcome.

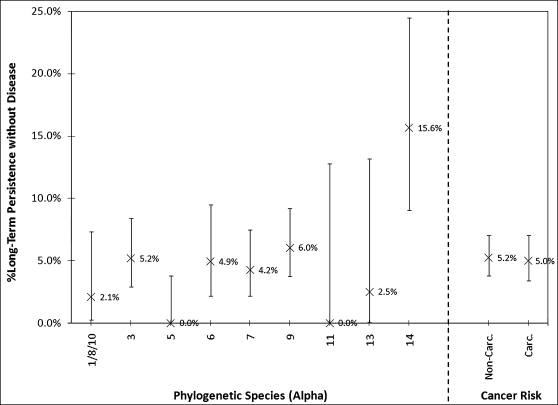

Among the common HPV genotypes in the study population (ie, those for which there were ≥20 infections detected at baseline), the most likely to establish LTP by our definition were HPV-71 (n = 96; LTP: 15.6%; 95% CI, 9.0%-24.5%]), HPV-16 (n = 82; LTP: 12.2%; 95% CI, 6.0%-21.3%]), and HPV-45 (n = 37; LTP: 8.1%; 95% CI, 1.7%-21.9%]). Grouped by phylogenetic species, a14 (which included only HPV-71 here; HPV-90 and HPV-106 were not detected), a9 (which included HPV-16; n = 331; LTP: 6.0%; 95% CI, 3.7%-9.2%]), and a3 (n = 290; LTP: 5.2%; 95% CI, 2.9%-8.4%]) were the most likely to establish long-term persistence (Figure 2). By contrast, no infections with HPV genotypes in a5 species, which includes HR–HPV-51, established long-term viral persistence without CIN2+ (96 [LTP, 0%; 95% CI, 0.0%-3.8%]).

Figure 2.

Percentage of prevalently-detected human papillomavirus (HPV) infections that demonstrated long-term HPV persistence by groups of HPV genotypes defined by phylogenetic species or cancer risk. Binomial 95% confidence intervals for groups of HPV genotypes are shown as vertical bars.

There was no significant difference in the likelihood of long-term viral persistence between carcinogenic and non–HR-HPV genotypes (5.2% vs 5.0%, respectively; P = .9, by the Fisher exact test) in this group of women in which women with CIN2+ were excluded.

Placed into context, among all women in the actively observed subcohort, women who tested positive for HR-HPV at baseline (n = 636) were twice as likely to have an outcome of a diagnosis of CIN2+ during follow-up than an outcome of LTP (without CIN2+) (61 vs 27). Conversely, women who tested positive for non–HR-HPV at baseline (n = 431) were 4-fold less likely to have an outcome of CIN2+ during follow-up than an outcome of LTP (without CIN2+) (7 vs 31; P < .001).

Because women who had LTP without CIN2+ were very different from those who cleared infections, we matched 47 (81%) of 58 women with LTP without CIN2+ to 480 (71%) of 678 women whose infections cleared on the number of enrollment HPV genotypes and the enrollment age (±5 years). This subset of 47 women with LTP had a total of 53 long-term persistent HPV infections (42 women had single LTP, 4 had 2 LTPs, and 1 had 3 LTPs). Because matching was not restricted in any way (eg, the number of control subjects matched to case patients and the number of times a control subject was used in a match), the cases had 1–163 matched control subjects, and each control subject was matched with 1–9 case patients. The 12 case patients with LTP for whom we could not find matches were older (median age, 68 vs 54 years; P < .001) and had more HPV genotypes detected at baseline (median, 4 vs 2; P < .001) than women with LTP for who we matched to women who cleared their infections.

In the conditional logistic model (Table 2) that adjusted on the enrollment age, the number of follow-up visits, and whether a woman reported a new sexual partner during follow-up, women with LTP were less likely to have had ≥2 sexual partners in their lifetime at the time of enrollment, compared with women who cleared their infections (OR for model, 0.52 [95% CI, 0.28-0.96]; OR for model 2, 0.48 [95% CI, 0.25-0.90]). Women with LTP were significantly more likely to have a new infection detected at ≥3 time points (OR for model 2, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.2-5.6). Covariates such as smoking, parity, and oral contraceptive use, considered cofactors for cervical cancer development [14], were not associated with LTP without CIN2+.

Table 2.

Conditional Logistic Regression Model to Calculate Odds Ratios (OR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (95%CI) as Measures of Association of Covariates with Long-term HPV Persistence without Disease (LTP) versus Clearance.

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Marital Status (Enrollment) | ||||

| Single (ref) | 1.0 | –– | 1.0 | –– |

| Separated or Divorced | 1.1 | 0.33–3.5 | 1.1 | 0.31–3.4 |

| Widowed | 1.0 | 0.26–4.0 | 0.99 | 0.25–3.9 |

| Single | 0.45 | 0.16–1.3 | 0.51 | 0.18–1.4 |

| Lifetime Number of Sexual Parners (Enrollment) | ||||

| 1 | 1.0 | –– | 1.0 | –– |

| 2 or more | 0.52 | 0.28–0.96 | 0.48 | 0.25–0.90 |

| Number of Infections (Follow-Up) | ||||

| 0 | 1.0 | –– | ||

| 1 or more | 1.6 | 0.83–3.0 | ||

| Number of Infections, 3 or more positive visits (Follow-Up) | ||||

| 0 | 1.0 | –– | ||

| 1 or more | 2.6 | 1.2–5.6 | ||

NOTE. Women who cleared to their infections were matched to women with LTP on the number of HPV genotypes detected at baseline and enrollment age +/−5 years. The variables were mutually adjusted for each other, and also adjusted for enrollment age, number of visits in follow-up, and number of new sexual partners reported during follow-up. Model 1 included a variable for any new HPV infection detected after baseline; Model 2 included a variable for any new HPV infection detected after baseline that tested positive at 3 or more visits. Ref = reference group.

Finally, among the 810 women included in this subcohort, we observed 753 newly detected HPV infections, of which 20 persisted (in 19 women; median age, 48 years) for ≥3 years (median duration, 4.3 years) to the end of the study. There were no significant differences in the distribution of HPV genotypes by phylogenetic species or groups between prevalent and incident LTP without CIN2+ (P =.3).

DISCUSSION

Here we described in detail the occurrence of long-term HPV persistence without detectable precancer, ≥3 years after being prevalently detected and therefore possibly already of much longer duration than newly appearing infections. Women with long-term HPV persistence of their prevalently detected infections were much older than women with other viral outcomes, as we reported previously with less-stringent criteria (ie, testing positive for the same HPV genotype at baseline and 5 or 6 year anniversary visit) [15]. Some older women may be unable to control or clear their HPV infection(s) because of age-related immune senescence [16, 17]. We also observed an inverse relationship between lifetime number of sexual partners and the likelihood of having a long-term persistent HPV infection. We believe this to be a chance association, although we cannot rule out that increased past exposure, as measured by number of sexual partners, might have increased the likelihood of exposure and therefore immunity. Most interestingly, we observed that women with long-term viral persistence were more likely to have HPV coinfections, especially those of longer (≥1 year) duration, even after adjustment for sexual behaviors, suggesting an unmeasured susceptibility factor.

We note that there was a similar number of HPV-positive women whose subsequent HPV patterns were classified as ambiguous and were excluded from definition of long-term viral persistence as those women who were classified as having LTP. On average, these women with ambiguous viral patterns were younger than those with long-term viral persistence and were slightly older than women who were classified as clearing their HPV infections (data not shown). Speculatively, some of the women with ambiguous viral patterns may also have LTP but because they are younger and perhaps have more robust immune responses to the HPV infection, detection of their persistent infection was intermittent due to the infection being occasionally suppressed a viral levels less than the limits of detection. Thus, our rigorous definition for persistence may have led to identifying primarily older women and therefore certain HPV genotypes preferentially found in cervical specimens in older women [18].

We observed some interesting patterns of long-term HPV persistence related to HPV phylogeny. First, we never observed long-term persistence for almost 100 infections by HPV genotypes in the a5 species, which contain 1 certain HR-HPV genotype (HPV-51) and several borderline HR-HPV genotypes that certainly can cause precancerous lesions [12, 19, 20]. Second, non–HR-HPV genotypes were equally capable of persisting as HR-HPV genotypes, once those infections that developed into precancerous lesions were excluded; inclusion of precancerous lesions in our definition of persistent infection would not change our observations appreciably, except that HPV-16 would be by far the most persistent HPV genotype (data not shown) [21]. Almost 16% of all HPV-71 infections demonstrated long-term persistence, but unlike HPV-16 infections, these infections carry no risk of cancer. Third, HPV-16, the most carcinogenic HPV genotype, can persist for many years without detectable evidence of causing disease (see Table 3a for an anecdotal example).

Table 3.

A Case with Prevalently- and Incidentally-detected (HPV-83 and HPV-81, respectively) Long-term Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Persistence (A) and a Case of Long-term HPV-16 Persistence (B), Both without Evidence of Clinical Disease

| A. Enrollment age: 69 years | ||||||||

| Time since | Visit | Costa Rica | Johns Hopkins | Thin-Prep | Thin-Prep | Cervigram | PCR Test | Colposcopy |

| enrollment (months) | Type | Pap Result | Pap Result | US | Costa Rica | Result | Results | Impression |

| 0 | Screen | Reactive | Missing | ASC-US | Negative | 66,71,83 | ||

| 13 | Screen | Koil. Atyp | Reactive | ASC-US | Negative | 59,71,82,82v,83 | ||

| 19 | Screen | Reactive | Normal | Normal | Negative | 81,83,89 | ||

| 28 | Screen | Reactive | ASC-US | Negative | 83 | |||

| 36 | Screen | Reactive | ASC-US | Negative | 32,81,83 | |||

| 43 | Screen | Reactive | ASC-US | Negative | 32,81,83 | |||

| 50 | Screen | Reactive | Reactive | Negative | 81,83 | |||

| 58 | Screen | Reactive | Normal | Negative | 32,81,83 | |||

| 66 | Screen | Reactive | Normal | Reactive | Negative | 32,81,83 | ||

| 84 | Screen | Reactive | Normal | Reactive | Negative | 32,81,83 | ||

| 98 | Colpo | Normal* | ||||||

| B. Enrollment Age: 54 Years | ||||||||

| Time Since | Visit | Costa Rica | Johns Hopkins | Thin-Prep | Thin-Prep | Cervigram | PCR Test | Colposcopy |

| Enrollment (months) | Type | Pap Result | Pap Result | US | Costa Rica | Result | Results | Impression |

| 0 | Screen | Normal | ASC-US | Reactive | Negative | 16 | ||

| 2 | Colpo | 16 | Normal | |||||

| 13 | Screen | Reactive | Reactive | Normal | Negative | 16 | ||

| 25 | Screen | Inadequate | Normal | Normal | Negative | 16,45 | ||

| 38 | Screen | Normal | Normal | Negative | 16 | |||

| 50 | Screen | Reactive | Normal | Negative | 16,59,61,67 | |||

| 61 | Screen | ASC-US | Normal | Negative | 16,84 | |||

| 84 | Screen | Reactive | Normal | Reactive | Negative | 16,84 | ||

| 95 | Colpo | Normal | ||||||

| 103 | Postcolp | Normal | ||||||

| 105 | Colpo | Normal | ||||||

NOTE. Bold face type highlights the prevalently-detected long-term persistent HPV genotype; underlined type highlights the incidentally-detected long-term persistent HPV genotype. *Punch biopsy was diagnosed as normal. ASC-US, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; Koil. Atyp, koilocytotic atypia; Reactive, reactive changes.

The observed patterns raise some important biological questions about HPV persistence. First, is viral persistence by HR-HPV genotypes leading to the development of cervical precancer the same phenomenon as viral persistence in the absence of disease? Or is persisting HR-HPV infection without detectable cervical disease really a microscopic precancerous lesion that has gone undetected? Second, what is the physical state—episomal, integrated, or both—of the persisting viral infection by the HR-HPV genotype? What is the viral methylation patterns related to viral outcomes? And third, do non–HR-HPV genotypes persist by the same mechanism(s) as HR-HPV genotypes? The answers to these questions may provide insights to poorly understood or unknown aspects of the natural history of HPV infection, including whether and how often HPV can establish a viral latent state and the molecular switches leading to progression.

Within the same subcohort of women who were actively observed and who lacked detectable CIN2+, we found a few examples of newly appearing infections that persisted for ≥3 years (data not shown; n.b., these are a subset of newly detected HPV infections defined for model 2). The distributions of HPV genotypes within phylogenetic species for the newly detected infections and prevalently detected infections were roughly similar. In general, the newly detected infections occurred in younger women than the prevalently detected infections. Some newly appearing infections occurred in women with prevalently detected, long-term persistent infection (Table 3a). Whether these newly detected infections represent truly new infections or reactivation of latent infections cannot be readily determined.

The limitations of this analysis of prevalently-detected women with LTP (without CIN2+) are that the data are both left and right censored—that is, we do not know the history of the infection prior to enrollment and the outcome of the infection after exiting the study. Some women were excluded from this analysis because they received a diagnosis of CIN2+ but could have had other infections that persisted without causing CIN2+. We cannot be certain when these women first acquired these infections in the cervix or vagina and, therefore, how long these infections were present before enrollment, only that they endured for a median of 7 years after enrollment; anecdotally, 22 (79%) of 28 long-term persistent HPV infections (in 25 women) were still detected during the conduct of ancillary studies, a median of 2.2 years after the end of the main cohort study. We also do not know longer-term risks of cervical precancer or cancer following this phenomenon of LTP.

We recognize that the choice of PCR primers may have influenced our result. Despite efforts to make primers systems to target a broad range of HPV genotypes for uniform amplification, different primers undoubtedly have different HPV-genotype specificity [22] that may have influenced our findings.

Finally, with the introduction of HR-HPV DNA testing into cervical cancer screening in older women (ie, those aged 30–35 years and older), most women with evidence of persistent HPV infection will be at high risk of CIN2+ but a small percentage of women will be identified as persistently HPV positive for many years without CIN2+. In all likelihood, most of these women who are repeatedly positive for any HR-HPV genotype will actually have long-term, HPV genotype-specific viral persistence (ie, long-term persistence is a clinical reality albeit uncommon one).

The clinical implications and best patient management for the approximately 1 in 20 HPV-positive women who, by our definition, will have long-term viral persistence without evidence of cervical disease among those with an index positive HPV test are uncertain. In places where HR-HPV testing has been introduced, long-term persistence without precancer has been observed (Dr. Walter Kinney, Kaiser Permanente Northern California; personal communication) but not quantified. Although there are certainly anecdotal experiences of persistent mild cytological abnormalities, there are sparse reports in the literature regarding the outcome of this phenomenon, which is almost certainly the result of long-term HPV viral persistence. One study [23] that excised the cervical tissue of 102 women following ≥4 borderline or mildly abnormal smears and no colposcopic evidence of high-grade disease found only 11 cases (∼11%) of undiagnosed CIN2/3. Thus, although immediate excision provides the greatest safety, almost 90% of women would be overtreated. Another management approach would be a more aggressive colposcopic exam, including 4-quadrant microbiopsies and endocervical curettage to maximize disease ascertainment without excision [24].

Funding

National Institutes of Health (N01-CP-21081, N01-CP-33061, N01-CP-40542, N01-CP-50535, N01-CP-81023, intramural program, CA78527 to RB). The Guanacaste cohort (design and conduct of the study, sample collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data) for the enrollment and follow-up phases were supported [in part] by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services.

References

- 1.McCredie MR, Sharples KJ, Paul C, et al. Natural history of cervical neoplasia and risk of invasive cancer in women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:425–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostor AG. Natural history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a critical review. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1993;12:186–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nasiell K, Roger V, Nasiell M. Behavior of mild cervical dysplasia during long-term follow-up. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67:665–9. doi: 10.1097/00006250-198605000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nasiell K, Nasiell M, Vaclavinkova V. Behavior of moderate cervical dysplasia during long-term follow-up. Obstet Gynecol. 1983;61:609–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plummer M, Schiffman M, Castle PE, Maucort-Boulch D, Wheeler CM. A 2-year prospective study of human papillomavirus persistence among women with a cytological diagnosis of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance or low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1582–9. doi: 10.1086/516784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez AC, Schiffman M, Herrero R, et al. Rapid clearance of human papillomavirus and implications for clinical focus on persistent infections. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:513–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson H, Kelsall G, Tellier P, et al. The natural history of type-specific human papillomavirus infections in female university students. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:485–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franco EL, Villa LL, Sobrinho JP, et al. Epidemiology of acquisition and clearance of cervical human papillomavirus infection in women from a high-risk area for cervical cancer. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1415–23. doi: 10.1086/315086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bratti MC, Rodriguez AC, Schiffman M, et al. Description of a seven-year prospective study of human papillomavirus infection and cervical neoplasia among 10 000 women in Guanacaste, Costa Rica [Description de un estudio prospectivo de siete anos sobre la infeccion por el virus del papiloma humano y el cancer cervicouterino en 10 000 mujeres de Guanacaste, Costa Rica] Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2004;15:75–89. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892004000200002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herrero R, Schiffman MH, Bratti C, et al. Design and methods of a population-based natural history study of cervical neoplasia in a rural province of Costa Rica: the Guanacaste project. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 1997;1:362–75. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49891997000500005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castle PE, Schiffman M, Gravitt PE, et al. Comparisons of HPV DNA detection by MY09/11 PCR methods. J Med Virol. 2002;68:417–23. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, et al. A review of human carcinogens–part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:321–2. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernard HU, Burk RD, Chen Z, van Doorslaer K, Hausen H, de Villiers EM. Classification of papillomaviruses (PVs) based on 189 PV types and proposal of taxonomic amendments. Virology. 2010;401:70–9. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castellsague X, Munoz N. Chapter 3: cofactors in human papillomavirus carcinogenesis–role of parity, oral contraceptives, and tobacco smoking. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2003;31:20–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castle PE, Schiffman M, Herrero R, et al. A prospective study of age trends in cervical human papillomavirus acquisition and persistence in guanacaste, costa rica. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1808–16. doi: 10.1086/428779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Pineres AJ, Hildesheim A, Herrero R, et al. Persistent human papillomavirus infection is associated with a generalized decrease in immune responsiveness in older women. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11070–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Einstein MH, Schiller JT, Viscidi RP, et al. Clinician's guide to human papillomavirus immunology: knowns and unknowns. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:347–56. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castle PE, Jeronimo J, Schiffman M, et al. Age-related changes of the cervix influence human papillomavirus type distribution. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1218–24. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith JS, Lindsay L, Hoots B, et al. Human papillomavirus type distribution in invasive cervical cancer and high-grade cervical lesions: a meta-analysis update. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:621–32. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castle PE, Cox JT, Jeronimo J, et al. An analysis of high-risk human papillomavirus DNA-negative cervical precancers in the ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study (ALTS) Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:847–56. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318168460b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schiffman M, Herrero R, Desalle R, et al. The carcinogenicity of human papillomavirus types reflects viral evolution. Virology. 2005;337:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gravitt PE, Viscidi RP. Measurement of exposures to human papillomavirus. In: Rohan TE, Shah KH, editors. Cervical cancer: from etiology to prevention. 1st ed. Netherlands: Springer; 2004. pp. 119–42. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pisal N, Sindos M, Mansell ME, Freeman-Wang T, Singer A. Persistent minor smear abnormalities: is large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ) the solution? J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;23:528–30. doi: 10.1080/0144361031000153792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pretorius RG, Zhang WH, Belinson JL, et al. Colposcopically directed biopsy, random cervical biopsy, and endocervical curettage in the diagnosis of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia II or worse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:430–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]