Abstract

Background

Studies from several countries indicate that welders experience increased risk of mortality and morbidity from ischaemic heart disease. Although the underlying mechanisms are unclear, vascular responses to particulate matter contained in welding fumes may play a role. To investigate this, we studied the acute effects of welding fume exposure on the endothelial component of vascular function, as measured by circulating adhesion molecules involved in leukocyte adhesion (sICAM-1 and sVCAM-1) and coagulation (vWF).

Methods

A panel of 26 male welders was studied repeatedly across a 6 h work-shift on a high exposure welding day and/or a low exposure non-welding day. Personal PM2.5 exposure was measured throughout the work-shift. Blood samples were collected in the morning (baseline) prior to the exposure period, immediately after the exposure period, and the following morning. To account for the repeated measurements, we used linear mixed models to evaluate the effects of welding (binary) and PM2.5 (continuous) exposure on each blood marker, adjusting for baseline blood marker concentration, smoking, age and time of day.

Results

Welding and PM2.5 exposure were significantly associated with a decrease in sVCAM-1 in the afternoon and the following morning and an increase in vWF in the afternoon.

Conclusions

The data suggest that welding and short-term occupational exposure to PM2.5 may acutely affect the endothelial component of vascular function.

Welders experience an increased risk of mortality and morbidity due to ischaemic heart disease.1–4 While the reasons are unclear, fine particulate matter (mass median aerodynamic diameter ≤2.5 µm (PM2.5)) contained in welding fume may play a role. Numerous air pollution studies associate PM2.5 exposures with adverse cardiovascular events including death,5–7 myocardial infarction, 8 myocardial ischaemia9 and arrhythmia10 within hours to days of exposure. The mechanisms by which inhalation of PM2.5 leads to adverse cardiovascular responses is unclear, however a growing body of evidence suggests that short-term exposure elicits acute alterations in vascular function. 11–18

We previously reported that welding fume exposure and its PM2.5 component were associated with acute alterations in the augmentation index, a measure of vascular function that is correlated with arterial stiffness.19 In this current study, we use a repeated measures panel study design to investigate the short-term effect of exposure to welding fume on circulating adhesion molecules, including soluble inter-cellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1), soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (sVCAM-1), which are involved in leukocyte adhesion, and von Willebrand factor antigen (vWF:Ag), a pro-coagulatory molecule. Circulating levels of these proteins are often used as markers of endothelial cell activation and function, as these markers are released by endothelial cells into the circulation upon interaction with stimulating agents such as inflammatory cytokines. All three biological markers are increased in individuals with cardiovascular disease and predict future risk of adverse cardiovascular events and stroke to varying degrees.20,21 We hypothesised a priori that welding fume exposure would be associated with increases in circulating biomarkers related to endothelial function and that there would be positive exposure–response relationships with work-shift PM2.5 concentrations.

METHODS

The study population consisted of male boilermaker construction workers (“boilermakers”) recruited from a local union in Massachusetts whose membership is predominantly male. Boilermakers are responsible for building, installing, maintaining and repairing power-generating boilers. Recruitment was performed primarily among apprentices during regularly scheduled welding classes, although experienced journeymen were also invited to participate to increase the number of participants. A panel of 27 individuals was recruited into the study in the winter of 2006 over five weekends; however, one of the panel, an immune-compromised individual, was excluded from the study.

All data collection was conducted at the union hall and attached welding school which consisted of a large room outfitted with 10 welding booths that each measured approximately 16 square feet (39″×59″) and 103″ high. Each welding booth was covered by a curtain and was equipped with its own local exhaust ventilation. During classes, participants received instruction and trained in welding for approximately 6 h. The most common type of welding performed was manual metal arc welding on mild (manganese alloys) and stainless steel (chromium and nickel alloys) bases. As reviewed by Antonini, studies on welding fume particles have shown the particles to be ≤0.50 µm in diameter.22

We monitored workers during winter (when there is less boilermaker work) to minimise welding fume and occupational PM2.5 exposure prior to the study. Ideally, participants would not have been exposed to welding fumes for at least 48 h prior to participating in the study; however, some worked or practiced welding the day before monitoring, but we did not exclude these individuals from the study. To assess potential carryover effects of previous exposures in the analyses, we collected information on exposure to welding fume the day prior to monitoring (yes/no) from each participant.

Boilermakers were also asked to participate on a separate day while performing office or bookwork at the union hall in a room adjacent to the welding room. Those who participated on these non-welding days provided a low-exposure comparison group which minimised potential confounding by between-person factors. For those who participated on both days, the order of exposure differed across participants, with some first monitored when welding, and others first monitored when not welding. In addition, the two monitoring days were separated by at least 1 week. The Institutional Review Board of the Harvard School of Public Health approved the study protocol and all participants gave written informed consent.

Exposure assessment

Personal exposure to PM2.5 was measured throughout the course of the 6 h work-shift for all participants. Prior to the start of the welding or non-welding period, participants were given their personal air sampling equipment. The gravimetric particulate samplers were placed within the workers’ breathing zone to measure exposure to PM2.5 throughout the work-shift or equivalent non-welding period. Study personnel periodically checked the samplers and pumps throughout the course of the day to ensure that the samplers were correctly worn in the breathing zone and that the air flow was not blocked. The gravimetric sample was collected onto a 37 mm polytetrafluoroethylene membrane filter (Gelman Laboratories, Ann Arbor, MI) using a KTL cyclone (GK2.05SH, BGI, Waltham, MA) with a 50% aerodynamic diameter cutpoint of 2.5 µm, used in line with a personal pump drawing 3.5 l/min of air. The polytetrafluoroethylene filter was encased in a cassette and placed downstream of the cyclone. The filters were weighed before and after sampling on a MT5 microbalance (Mettler-Toledo, Columbus, OH) after equilibrating for a minimum of 24 h in a temperature and humidity controlled room. The gravimetric PM2.5 mass concentration was calculated by dividing the mass collected on the filter by the sampled air volume. All samples were blank corrected. To account for differences in sampling times, PM2.5 concentrations were standardised to 8 h time weighted averages (TWA). One TWA PM2.5 concentration was assigned for each worker.

Collection and analysis of blood samples

Blood samples were collected by venous puncture prior to the start of exposure, immediately after, and the following morning. The samples from each draw were collected into tubes containing 3.2% sodium citrate (for vWF:Ag) and serum separator tubes (for sICAM-1 and sVCAM-1). Blood samples were centrifuged immediately and plasma samples were aliquoted into cryogenic storage tubes and kept on dry ice until transport back to the laboratory at the Harvard School of Public Health where they were stored in a −80°C freezer until analysis. Quantification of serum marker levels was conducted in-house approximately 2 months after blood collection using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method with commercially available kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN (sICAM-1 and sVCAM-1) and American Diagnostica, Stamford, CT (vWF-Ag)). For the leukocyte adhesion molecules, we restricted the analysis to self-reported Caucasian individuals (thereby excluding one African-American participant), as the expression of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 and therefore concentrations of their soluble forms have been reported to vary substantially by race and ethnicity.23,24

All samples from each participant were analysed in duplicate and in one batch to avoid between-batch analytical variation. For each duplicate sample, any sample with a coefficient of variation >20% required that all samples from that participant be re-run until the coefficient of variation was ≤20%. The performance of the assays was monitored with standard quality control procedures including the analysis of blinded pooled samples. The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were: 7.1% and 9.1% for sICAM-1; 5.3% and 9.0% for sVCAM-1; and 12.3% and 14.1% for vWF.

Collection of study population characteristics and other covariates

Information on demographics, medical history, medication usage, smoking history and occupational history was obtained using a self-administered modified standardised American Thoracic Society (ATS) questionnaire.25 In addition, information on smoking during the monitoring period was recorded on time activity sheets, as in previous studies of this population.26 Information on respirator use during the monitoring period was also collected.

Statistical analysis

To account for the correlation of repeated measures within person, we constructed linear mixed models for each of the three blood markers to determine the effect of welding exposure (binary) on afternoon and next morning serum marker concentrations. In addition to accounting for the correlation of the repeated measurements, the mixed models accommodated the imbalances in the data which arose from some individuals participating on only the welding day or not returning for the next morning measurement.27 We assumed that the data were missing at random, making the likelihood based inferences valid. To assess the exposure–response relationship, we also constructed separate models using the TWA work-shift PM2.5 concentrations (continuous) as the predictor. An autoregressive covariance matrix was chosen as the working covariance structure because it provided the lowest Akaike information criterion. Baseline blood marker concentration, taken prior to exposure measurements, was used as a predictor to control for individual factors that may influence blood marker levels. Age and smoking (yes/no) within the last 4 h of each afternoon and next morning blood draw were also controlled for in the models. In addition, to account for potential circadian variation in the blood markers, an indicator for time (next morning versus afternoon) was included in the models. To allow the effect of exposure to vary over time, we included an interaction term for weld (or PM2.5) and time. Regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for both the afternoon and the next morning blood marker levels were estimated from the models. For models evaluating the effect of continuous work-shift PM2.5 concentration, we performed additional subanalyses excluding individuals currently taking anti-hypertensive and lipid-lowering medications.

We also constructed models to account for the potential effects of welding exposure (yes/no) the day prior to monitoring by using indicator variables to reflect exposure conditions over the 2 days (ie, exposed the day prior to monitoring only, exposed the day of monitoring only, exposed both days, with the reference being unexposed on both days). In the model using PM2.5, an indictor for exposure status the day prior to monitoring was used in the model as well as its interaction with PM2.5. Residual plots and the distribution of the error terms were assessed to check the normality of the residuals and adequacy of model fits. Statistical significance for all testing was considered at the α = 0.05 level. Analyses were performed with SAS v 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

The study population is described in table 1. Among the 26 participants, 25 participated on a welding day and 15 participated on a non-welding day, with 14 individuals participating on both a welding day and a non-welding day. A total of 40 post-shift afternoon and 34 next morning samples were collected in total.

Table 1.

Characteristics of male welders in the study population

| Participants, n (%) | 26 (100) |

| White, n (%) | 24 (92.3) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 9 (34.6) |

| Age in years, mean (SD) (range) | 40 (11) (24–60) |

| Median years as a boilermaker (range) | 5 (<1–30) |

| Cardiopulmonary history, n (%) | |

| Chronic bronchitis | 1 (4) |

| Asthma | 1 (4) |

| High blood pressure | 5 (19) |

| Myocardial infarction | 1 (4) |

| Current medication usage, n (%) | |

| Anti-hypertensive medications | 5 (19) |

| Statins* | 3 (12) |

| Baseline blood marker levels, mean (SD) (range) | |

| sICAM-1 (ng/ml)† | 285 (59) (210–430) |

| sVCAM-1 (ng/ml)† | 596 (133) (409–874) |

| vWF:Ag (% normal) | 92 (30) (35–151) |

Also taking anti-hypertensive medication;

n = 25.

Those who participated on both exposure days were comparable to those who participated on only 1 day in terms of age, number of years as boilermaker, smoking status, lipids, and all three baseline blood marker levels (data not presented). The median duration as a boilermaker was 5 years, suggesting that about half of the participants were apprentices and half were more experienced journeymen, given that the apprenticeship program for boilermakers typically lasts 4 years. The Spearman rank correlation coefficients were low for the biological markers: 0.12 (p=0.57) for sICAM-1 and sVCAM-1; −0.15 (p=0.47) for sICAM-1 and vWF; and 0.08 (p=0.69) for sVCAM-1 and vWF:Ag.

On a non-welding day, the average sampling time was 7.1 h (SD 1.2) and on a welding day, 6.7 h (SD 1.7). On a non-welding day, the median PM2.5 8 h TWA exposure was 0.04 mg/m3 (range: 0.01–0.19 mg/m3) and on a welding day, 0.39 mg/m3 (range: 0.03–2.62 mg/m3). The overall median PM2.5 concentration among the 40 personal exposure samples was 0.39 mg/m3 (inter-quartile range: 0.05–0.58 mg/m3). None of the workers wore respirators while welding.

The associations between the leukocyte adhesion molecules and welding exposure are presented in table 2. The afternoon concentration of sVCAM-1 was lower on an exposed welding day versus a non-welding day and the difference was statistically significant. The lower sVCAM-1 concentration associated with welding exposure persisted the following morning, although the association was not as strong as compared to the previous afternoon, or statistically significant.

Table 2.

Association between blood marker concentrations and welding exposure (yes/no)*

| Afternoon | Next morning | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β Coefficient (95% CI) | p Value | β Coefficient (95% CI) | p Value | |

| sVCAM-1 (ng/ml) | −62.4 (−105.0 to −19.9) | 0.01 | −36.9 (−82.4 to 8.6) | 0.10 |

| sICAM-1 (ng/ml) | −6.7 (−28.9 to 15.5) | 0.52 | 0.6 (−28.6 to 29.8) | 0.97 |

| vWF:Ag (% normal) | 8.1 (0.1 to 16.1) | 0.05 | −3.4 (−17.1 to 10.3) | 0.60 |

Models adjusted for baseline blood marker concentration, smoking within 4 h of blood draw, age and time.

These results were supported when we examined the exposure–response relationship using work-shift PM2.5 and observed a decrease in the afternoon and next morning sVCAM-1 concentration with increasing exposure (table 3). As with the welding (yes/no) models, the next morning association between sVCAM-1 and PM2.5 was not as strong, or statistically significant, as compared with the association in the afternoon.

Table 3.

Association between blood marker concentrations and an inter-quartile range change in work-shift PM2.5 concentration (mg/m3)*

| Afternoon | Next morning | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β Coefficient† (95% CI) | p Value | β Coefficient (95% CI) | p Value | |

| sVCAM-1 (ng/ml) | −33.6 (−46.8 to −20.4) | <0.001 | −25.8 (−54.5 to 2.9) | 0.08 |

| sICAM-1 (ng/ml) | 2.7 (−3.0 to 8.4) | 0.34 | −2.1 (−8.5 to 4.4) | 0.52 |

| vWF:Ag (% normal) | 3.8 (−20.2 to 7.7) | 0.06 | 0.4 (−2.7 to 3.6) | 0.78 |

Models adjusted for baseline blood marker concentration, smoking within 4 h of blood draw, age and time.

Effect estimate is for an inter-quartile range increase in PM2.5 (0.05 to 0.58 mg/m3).

Some effect estimates associated with sICAM-1 were also negative, suggesting a decrease in relation to welding and increasing work-shift PM2.5; however, the results were inconsistent for welding and PM2.5 and not statistically significant (tables 2 and 3). Welding fume exposure was associated with a statistically significant increase in vWF:Ag in the afternoon but not the following morning (table 2). Using the work-shift PM2.5 as the exposure variable, there was a marginally statistically significant increase in the afternoon level of vWF:Ag as the exposure concentration increased (table 3), while there was no significant change the next morning.

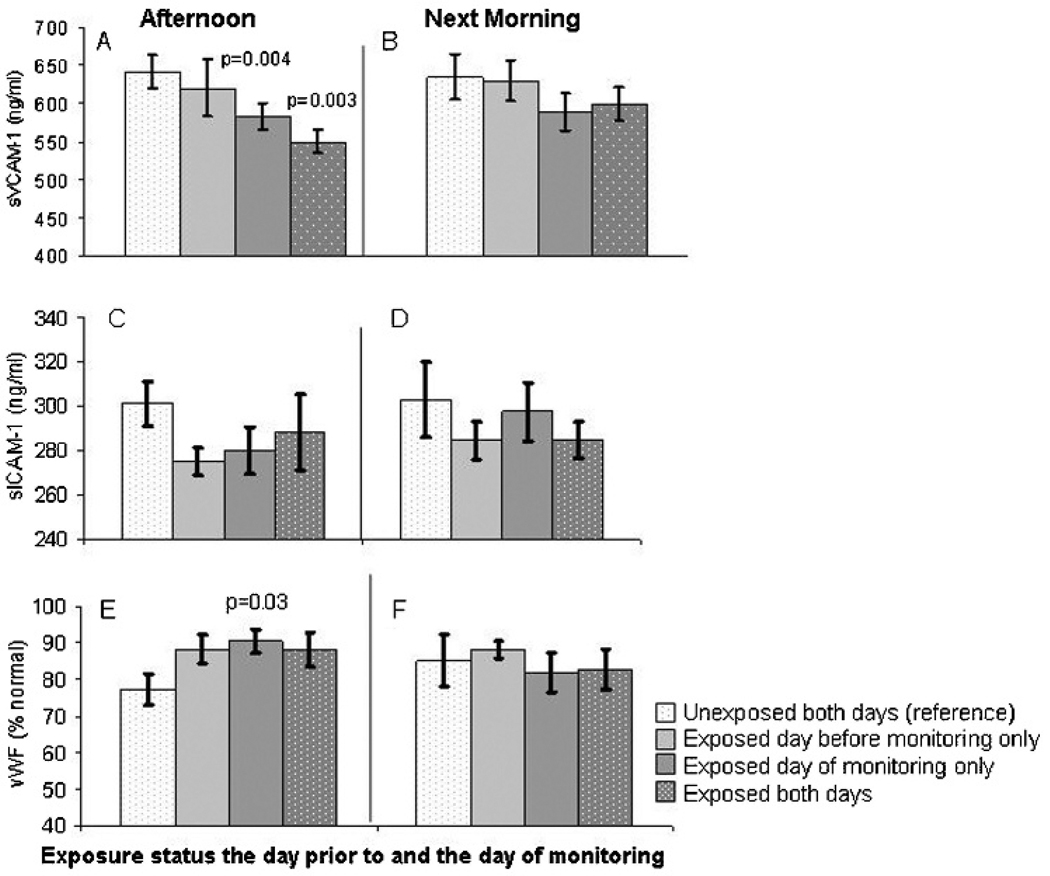

Among the 25 welding day participants, nine were exposed to welding fumes the day before monitoring, and among the 15 non-welding day participants, six were exposed the day before. All together, among the 40 person days of observation, 15 occurred 1 day after exposure to welding fumes. When we accounted for this previous day’s exposure, we found that exposure over 2 days in a row resulted in an even greater decline in sVCAM-1 in the afternoon as compared to no exposure on either day (p=0.003) (fig 1). However, when we modelled an interaction term for previous day’s exposure status and PM2.5, there were no statistically significant differences in the effect of PM2.5 for any of the three markers according to welding status the day prior to monitoring (data not presented).

Figure 1.

Adjusted mean (SE) blood marker concentrations by exposure status the day prior to and the day of monitoring. p Values obtained from mixed models and compare the mean concentration from each exposure scenario to the reference period (unexposed both days). The mean predicted level of sVCAM-1 was significantly lower in the afternoon after welding exposure on the day of monitoring only and after welding exposure 2 days in a row (A) versus being unexposed both days. No significant differences in the level of soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (sVCAM-1) were observed by exposure status the next morning (B). No significant differences in the level of soluble inter-cellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1) were observed by exposure status in the afternoon (C) or next morning (D). Levels of von Willebrand factor (vWF) were significantly higher in the afternoon after welding on the day of monitoring only (E). There were no differences in next morning vWF concentrations according to exposure status (F).

Exclusion of outlying residuals from the PM2.5 models did not appreciably change the results for each of the blood marker models. With regard to the exclusion of individuals taking anti-hypertensive and statin medications (n=5), the effect estimates for PM2.5 became stronger for all blood marker models and the association with next morning sVCAM-1 became statistically significant (sVCAM-1 decreased 31.4 ng/ml per inter-quartile range increase in PM2.5 concentration; 95% CI −60.5 to −2.4; p=0.03). Controlling for medication use in the models provided similar results although the effect of PM2.5 did not reach statistical significance for next morning sVCAM-1.

DISCUSSION

In this study of male boilermaker welders, short-term welding fume exposure was associated with changes in circulating markers related to endothelial function, a component of vascular function. Specifically, we observed an acute increase in vWF, a pro-coagulant, in the afternoon immediately after welding exposure, and a corresponding linear exposure–response relationship between the work-shift PM2.5 concentrations and levels of vWF. We also observed a decrease in sVCAM-1, an endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecule, immediately after 6 h of welding exposure, which was contrary to our a priori hypothesis that levels would increase after exposure. A model based on work-shift PM2.5 concentrations also yielded an inverse exposure–response relationship with sVCAM-1, suggesting that the PM2.5 component of the welding fume was at least partially responsible for the inverse association we observed with binary welding exposure. Results from crude paired analysis of the crossover participants supported these findings (data not presented).

As a molecule involved in the adhesion of platelets, the positive association between PM2.5 exposure and vWF observed in this study suggests a pro-coagulant effect of PM2.5 exposure, which is consistent with findings from another small study of welding fume exposure.28 Our findings for vWF are also consistent with a study of male highway patrol officers in which vehicular PM2.5 was associated with an increase in vWF.12 Positive associations between vWF and ambient PM2.5 have also been observed among individuals with diabetes13,17 and coronary heart disease.15 vWF is synthesised and stored in endothelial cells, and its release is indicative of stimulation of or damage to endothelial cells,29 which may occur via interaction with proinflammatory cytokines.

We expected that the concentration of leukocyte adhesion molecules would increase with exposure, as such an association has been observed among individuals with diabetes and coronary artery disease.17,30 However, contrary to our expectation, sVCAM-1 decreased after welding exposure and an inverse relationship with PM2.5 concentrations was observed. The different direction of effect found in this study as compared to the previous studies may reflect differences in the underlying inflammatory state of the individuals studied. The unexpected relationship observed in these relatively young healthy boilermakers was also recently observed in a study of Mexico City children with high cumulative exposures to particulate air pollution. These children had significantly decreased levels of sVCAM-1 and sICAM-1 compared to children with substantially lower exposure to PM2.5.31 The authors suggested that the observed down-regulation of adhesion molecules could be related to the anti-inflammatory effects of IL10, high concentrations of which were present in the Mexico City children. Interestingly, other pro-inflammatory cytokines were significantly higher in the exposed Mexico City children, which emphasises the complexity of the physiological and pathophysiological inflammatory and vascular responses to PM exposures.

Of note, using microarray gene expression techniques, we previously observed down-regulation of genes clustered into groups related to inflammatory responses, oxidative stress and intracellular signal transduction among boilermakers after exposure to welding fumes, which again points to the complexity of the biological pathways of response.32 Further research into the early biological responses to PM, including evaluation of responsible PM components, is needed to disentangle the complex mechanistic pathways.

We acknowledge that there are several limitations to this study, including the small sample size, which likely affected the precision of our estimates and may have precluded our ability to detect a statistically significant association with sICAM-1. Although the sample size was small, the panel study design with repeated measurements and the use of self-controls increased the efficiency of our sample size. We were still limited, however, in our ability to evaluate potential effect modification by factors such as duration as a boilermaker and smoking. It is possible that experience as a boilermaker, which would correspond to cumulative occupational PM2.5 exposure, may modify the associations between short-term PM2.5 exposure and acute effects on endothelial vascular health and that the inverse association observed between exposure and sVCAM-1 could be explained by an averaging of differential effects among apprentices and journeymen or smokers and nonsmokers. However, we were not able to investigate these potential interactions due to our small sample size. It is unlikely that duration as a boilermaker (ie, apprentice versus journeyman) confounded our observations because each individual served as his own control due to the repeated measures study design, and thus factors that vary between persons were of minimal concern as potential confounders.

It is worth noting that the welders were exposed to particles from other sources such as grinding and cutting, which produces larger sized particles. However, the effects observed in this study were likely due to the PM2.5 contained in welding fume and not to the larger sized particles, as larger size fraction particles (eg, from welding slag, grinding dust and slagging dusts) are not likely to penetrate into the alveolar region of the lungs and be able to produce a systemic response. Moreover, the observed exposure–response relationship with PM2.5 suggests that the observed effects were due to PM2.5 and not larger particles, as larger size particles produced from activities other than those that generate PM2.5 are not likely to be correlated with PM2.5. Only if PM2.5 and larger particles are correlated would this potentially account for all or some of the subclinical effects observed.

A limitation of greater concern was potential carryover effects from the occurrence of recent welding fume exposures prior to the start of monitoring. However, we found that the interpretation of our main analyses did not change after controlling for prior exposure, although there were suggestions of prolonged effects which we were not able to adequately study because of our limited sample size. The longer term effects of exposure should be further studied by monitoring workers over longer periods of time with detailed information on welding and PM2.5 exposures. In addition, although we controlled for time-varying smoking patterns, residual confounding by smoking cannot be ruled out, especially for the association between PM2.5 and vWF.33 Further, lack of data on gaseous co-pollutants, a common concern in particulate air pollution studies, is another possible limitation of our study. However, a previous study in this cohort showed that concentrations of typical co-pollutants found in welding operations, O3 and NO2, were low and uncorrelated to the level of PM.34 In general, concentrations of these gases are low in manual metal arc welding under a variety of operating conditions35 and thus are not of major concern.

Our findings suggest that short-term occupational exposure to PM2.5 and welding fumes may acutely alter vascular health, specifically endothelial function, a component of vascular function, which over a working lifetime may cumulatively have an impact on long-term cardiovascular health. The interaction between duration of lifetime exposure to welding fumes and these alterations needs to be investigated for a clearer understanding of the biological mechanisms involved in the disproportionately poor cardiovascular health of welders. Additional larger studies, ideally with more repeated measures and biological markers of vascular function, are necessary to confirm these findings in other workers exposed to welding fumes and PM2.5.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of C Dobson, E Rodrigues, M Wang, L Su, A Nuernberg, M Chertok, M Jones, A Mehta, R Zhai and the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers, Local 29 in Quincy, Massachusetts to this research study.

Funding: The National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) (grant numbers ES009860 and ES00002) supported this work. SF was supported by National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) training grant T42 OH008416 and JC was supported by NIOSH and NIEHS training grants T42 OH008416 and T32 ES07069.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The Institutional Review Board of the Harvard School of Public Health approved the study protocol.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Newhouse ML, Oakes D, Woolley AJ. Mortality of welders and other craftsmen at a shipyard in NE England. Br J Ind Med. 1985;42:406–410. doi: 10.1136/oem.42.6.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moulin JJ, Wild P, Haguenoer JM, et al. A mortality study among mild steel and stainless steel welders. Br J Ind Med. 1993;50:234–243. doi: 10.1136/oem.50.3.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sjogren B, Fossum T, Lindh T, et al. Welding and ischemic heart disease. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2002;8:309–311. doi: 10.1179/107735202800338597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hilt B, Qvenild T, Rømyhr O. Morbidity from ischemic heart disease in workers at a stainless steel welding factory. Norsk Epidemiologi. 1999;9:21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz J, Dockery DW, Neas LM. Is daily mortality associated specifically with fine particles? J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 1996;46:927–939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klemm RJ, Mason RM, Jr, Heilig CM, et al. Is daily mortality associated specifically with fine particles? Data reconstruction and replication of analyses. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2000;50:1215–1222. doi: 10.1080/10473289.2000.10464149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostro B, Broadwin R, Green S, et al. Fine particulate air pollution and mortality in nine California counties: results from CALFINE. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:29–33. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peters A, Dockery DW, Muller JE, et al. Increased particulate air pollution and the triggering of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;103:2810–2815. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.23.2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pekkanen J, Peters A, Hoek G, et al. Particulate air pollution and risk of ST-segment depression during repeated submaximal exercise tests among subjects with coronary heart disease: the Exposure and Risk Assessment for Fine and Ultrafine Particles in Ambient Air (ULTRA) study. Circulation. 2002;106:933–938. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000027561.41736.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peters A, Liu E, Verrier RL, et al. Air pollution and incidence of cardiac arrhythmia. Epidemiology. 2000;11:11–17. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200001000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brook RD, Brook JR, Urch B, et al. Inhalation of fine particulate air pollution and ozone causes acute arterial vasoconstriction in healthy adults. Circulation. 2002;105:1534–1536. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013838.94747.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riediker M, Cascio WE, Griggs TR, et al. Particulate matter exposure in cars is associated with cardiovascular effects in healthy young men. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:934–940. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200310-1463OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao D, Heiss G, Chinchilli VM, et al. Association of criteria pollutants with plasma hemostatic/inflammatory markers: a population-based study. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2005;15:319–328. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Neill MS, Veves A, Zanobetti A, et al. Diabetes enhances vulnerability to particulate air pollution-associated impairment in vascular reactivity and endothelial function. Circulation. 2005;111:2913–2920. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.517110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruckerl R, Ibald-Mulli A, Koenig W, et al. Air pollution and markers of inflammation and coagulation in patients with coronary heart disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:432–441. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200507-1123OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mills NL, Tornqvist H, Gonzalez MC, et al. Ischemic and thrombotic effects of dilute diesel-exhaust inhalation in men with coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1075–1082. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Neill MS, Veves A, Sarnat JA, et al. Air pollution and inflammation in type 2 diabetes: a mechanism for susceptibility. Occup Environ Med. 2007;64:373–379. doi: 10.1136/oem.2006.030023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tornqvist H, Mills NL, Gonzalez M, et al. Persistent endothelial dysfunction in humans after diesel exhaust inhalation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:395–400. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200606-872OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fang SC, Eisen EA, Cavallari JM, et al. Acute changes in vascular function among welders exposed to metal-rich particulate matter. Epidemiology. 2008;19:217–225. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31816334dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Roitman-Johnson B, et al. Plasma concentration of soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and risks of future myocardial infarction in apparently healthy men. Lancet. 1998;351:88–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)09032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Constans J, Conri C. Circulating markers of endothelial function in cardiovascular disease. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;368:33–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2005.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antonini JM. Health effects of welding. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2003;33:61–103. doi: 10.1080/713611032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwang SJ, Ballantyne CM, Sharrett AR, et al. Circulating adhesion molecules VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin in carotid atherosclerosis and incident coronary heart disease cases: the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) study. Circulation. 1997;96:4219–4225. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.12.4219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller MA, Sagnella GA, Kerry SM, et al. Ethnic differences in circulating soluble adhesion molecules: the Wandsworth Heart and Stroke Study. Clin Sci (Lond) 2003;104:591–598. doi: 10.1042/CS20020333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferris BG. Epidemiology Standardization Project (American Thoracic Society) Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;118(6 Pt 2):1–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen JC, Stone PH, Verrier RL, et al. Personal coronary risk profiles modify autonomic nervous system responses to air pollution. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48:1133–1142. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000245675.85924.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Interscience; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scharrer E, Hessel H, Kronseder A, et al. Heart rate variability, hemostatic and acute inflammatory blood parameters in healthy adults after short-term exposure to welding fume. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2007;80:265–272. doi: 10.1007/s00420-006-0127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lip GY, Blann A. von Willebrand factor: a marker of endothelial dysfunction in vascular disorders? Cardiovasc Res. 1997;34:255–265. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delfino RJ, Staimer N, Tjoa T, et al. Circulating biomarkers of inflammation, antioxidant activity, and platelet activation are associated with primary combustion aerosols in subjects with coronary artery disease. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:898–906. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calderon-Garciduenas L, Villarreal-Calderon R, Valencia-Salazar G, et al. Systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and activation in clinically healthy children exposed to air pollutants. Inhal Toxicol. 2008;20:499–506. doi: 10.1080/08958370701864797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Z, Neuburg D, Li C, et al. Global gene expression profiling in whole-blood samples from individuals exposed to metal fumes. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:233–241. doi: 10.1289/txg.7273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blann AD, Kirkpatrick U, Devine C, et al. The influence of acute smoking on leucocytes, platelets and the endothelium. Atherosclerosis. 1998;141:133–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y, Woodin MA, Smith TJ, et al. Exposure to fuel-oil ash and welding emissions during the overhaul of an oil-fired boiler. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2005;2:435–443. doi: 10.1080/15459620591034529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burgess WA. Recognition of health hazards in industry: a review of materials and processes. 2nd edn. New York: Wiley; 1995. [Google Scholar]