Abstract

Normal aging is associated with impairments in stimulus recognition. In the current investigation, object recognition was tested in adult and aged rats with the standard spontaneous object recognition (SOR) task or two variants of this task. On the standard SOR task, adult rats showed an exploratory preference for the novel object over delays up to 24 hours, whereas the aged rats only showed significant novelty discrimination at the 2 min delay. This age difference appeared to be due to the old rats behaving as if the novel object was familiar. To test this hypothesis directly, rats participated in a variant of the SOR task that allowed the exploration times between the object familiarization and the test phases to be compared, and this experiment confirmed that aged rats falsely “recognize” the novel object. A final control examined whether or not aged rats exhibited reduced motivation to explore objects. In this experiment, when the environmental context changed between familiarization and test, young and old rats failed to show an exploratory preference because both age groups spent more time exploring the familiar object. Together these findings support the view that age-related impairments in object recognition arise from old animals behaving as if novel objects are familiar, which is reminiscent of behavioral impairments in young rats with perirhinal cortical lesions. The current experiments thus suggest that alterations in the perirhinal cortex may be responsible for reducing aged animals’ ability to distinguish new stimuli from ones that have been encountered previously.

Keywords: aging, memory, perirhinal cortex, perception, rat

Introduction

The ability to discriminate novel stimuli from those that have been previously encountered is a basic prerequisite for accurate stimulus recognition. Electrophysiological (e.g. Erickson, Jagadeesh, & Desimone, 2000; Higuchi & Miyashita, 1996; Holscher, Rolls, & Xiang, 2003; Naya, Yoshida, & Miyashita, 2001), lesion (e.g. Barense et al., 2005; Baxter & Murray, 2001a, 2001b; Bussey, Duck, Muir, & Aggleton, 2000; Bussey, Muir, & Aggleton, 1999; Fahy, Riches, & Brown, 1993; Malkova, Bachevalier, Mishkin, & Saunders, 2001; Mumby, Glenn, Nesbitt, & Kyriazis, 2002; Nemanic, Alvarado, & Bachevalier, 2004; Prusky, Douglas, Nelson, Shabanpoor, & Sutherland, 2004; Winters & Bussey, 2005a; Winters, Forwood, Cowell, Saksida, & Bussey, 2004), and neuroimaging (e.g. Barense, Henson, Lee, & Graham, 2009; Brozinsky, Yonelinas, Kroll, & Ranganath, 2005; Pihlajamaki et al., 2004; Ranganath et al., 2004) studies all support the notion that the perirhinal cortex is one brain region that is essential for accurate stimulus recognition.

In rodents, the tendency to explore novel objects more than familiar ones can be exploited as a sensitive test of stimulus recognition (Ennaceur & Delacour, 1988). Such spontaneous object recognition (SOR) tasks do not require a rule to be learned, nor do they rely on positive or negative reinforcers such as food reward or foot shock (Ennaceur & Delacour, 1988). It has been shown that damage to the perirhinal cortex impairs performance on SOR tasks (Abe, Ishida, & Iwasaki, 2004; e.g. Ennaceur & Aggleton, 1997; Winters & Bussey, 2005b), but good performance on these tasks typically does not require an intact hippocampus (e.g., Forwood, Winters, & Bussey, 2005; Good, Barnes, Staal, McGregor, & Honey, 2007; O'Brien, Lehmann, Lecluse, & Mumby, 2006; Winters et al., 2004). Use of the SOR task therefore provides the opportunity to examine age-related cognitive decline that may occur independently and in parallel to changes in hippocampal function.

While it is well documented that normative aging processes affect a number of behaviors that require the medial temporal lobe, the impact of aging on object recognition has not been well-characterized, and the findings have been contradictory. Specifically, Cavoy and Delcour (1993) found no novelty discrimination deficits in 24 month old Wistar rats relative to younger animals (Cavoy & Delacour, 1993). This study, however, only used delays up to 5 min between the object familiarization and the test phases. Age-related decreases in novelty discrimination have been reported to occur at longer delay intervals (Bartolini, Casamenti, & Pepeu, 1996; de Lima et al., 2005; Pieta Dias et al., 2007; Pitsikas, Rigamonti, Cella, Sakellaridis, & Muller, 2005; Vannucchi, Scali, Kopf, Pepeu, & Casamenti, 1997). The performance measure most often reported to describe the preference a rat has for exploring the novel object relative to the familiar object is the “discrimination ratio” (Dix & Aggleton, 1999). The discrimination ratio is derived by calculating the difference in exploration time of a novel object compared to a familiar one, divided by the total exploration time. It is typically assumed that a reduced discrimination ratio reflects a reduced ability to recall an object that was previously experienced. Because a lower discrimination ratio can result from either an increase in exploration of the familiar object, or a decrease in exploration of the novel object, at least two different explanations can be offered to explain lower ratio values: 1) increased exploration of the familiar object would imply that the animal ‘forgot’ encountering that object previously, and this would reflect a memory deficit; 2) reduced exploration of the novel object would imply that the animal incorrectly identifies a novel object as familiar, and could indicate an impairment in novelty discrimination. These possible outcomes may have distinguishable neurobiological etiologies (Daselaar, Fleck, & Cabeza, 2006), leading to different conclusions regarding the nature of the deficit examined.

The relative contribution of “forgetting” versus a “decline in novelty discrimination” to age-associated impairments in object recognition has not been examined, and is therefore the focus of the current investigation. Three different SOR procedures were implemented in the present study. The first used standard SOR procedures in which a rat was first exposed to two identical objects during a ‘familiarization phase’. After a delay, the rat was then exposed to a copy of the familiar object and a novel object. The second procedure (Experiment 2) involved the simultaneous presentation of two identical objects during both the familiarization phase and the test phase (McTighe, Cowell, Winters, Bussey, & Saksida, 2008). This enabled a direct comparison of the amount of time spent exploring objects during the familiarization phase versus the test phase. This direct comparison is not possible with the standard SOR task because the test phase has two distinct objects with different stimulus features and the familiarization phase does not, thus the phases are distinguishable by more than just the relative familiarity of the objects. The third procedure (Experiment 3) involved changing both the room and the testing arena between the familiarization and test phases. Because incongruent contexts between sample and test phases encourages additional object exploration (Norman & Eacott, 2005), this procedure could assess the degree to which age-related changes in object recognition might be explained by habituation to object exploration in old animals. The spatial learning and memory abilities of all rats were also characterized using the Morris swim task (Morris, 1984) enabling a comparison between hippocampal-dependent spatial memory, and perirhinal-dependent stimulus recognition performance across age groups. The design of the present experiments allows a more exact determination of the source of the recognition impairment in aged rats and the extent to which deficits in this domain are associated with declines in hippocampal-dependent spatial memory.

Methods

Subjects and spatial memory testing

A total of forty-four young (7–9 months old) and fifty-one aged (24–25 months old) male F344 rats (from the National Institute on Aging's colony at Harlan-Sprague Dawley, Indianapolis, IN) participated in these behavioral experiments. The rats were housed individually in plexiglas guinea pig tubs and maintained on a reversed 12-hr light-dark cycle. All behavioral testing occurred during the dark phase of the rats’ light-dark cycle and each animal was given access to food and water ad libitum for the duration of these experiments.

After arriving, rats were handled by experimenters over several days for at least 5–10 minutes per day. After the animals stopped vocalizing and defecating during handling, and appeared calm when handled by experimenters, they were tested on the spatial and the visually-cued versions of the Morris swim task (Morris, 1984). Rats from the three different experiments were tested on the swim task separately. Thus, there were 3 squads of animals that completed spatial memory testing with each group containing between 24 and 36 rats. The Morris swim task procedures have been described in detail previously (e.g. Barnes, Rao, & McNaughton, 1996; Shen, Barnes, Wenk, & McNaughton, 1996). Briefly, during the spatial version of the Morris swim task, all animals were given 6 training trials per day over 4 consecutive days. During these trials, an escape platform was hidden below the surface of water, which was made opaque with non-toxic Crayola paint. Rats were released from seven different start locations around the perimeter of the tank, and each animal performed two successive trials before the next rat was tested. The order of the release locations was pseudo-randomized for each rat such that no rat was released from the same location on two consecutive trials. Immediately following the 24 spatial trials, the rats performed a probe trial in which the platform was removed and a rat swam in the pool for 60 sec (data not shown). Following the probe trial the animals were screened for visual ability with 2 days of cued visual trials (6 trials per day) in which the escape platform was above the surface of the water but the position of the platform changed between each trial. Rats’ performance on the swim task was analyzed offline with either in-house software (WMAZE, M. Williams) or a commercial software application (ANY-maze, Wood Dale, IL). Because different release locations and differences in swimming velocity produce variability in the latency to reach the escape platform, a corrected integrated path length (CIPL) was calculated to ensure comparability of the rats’ performance across different release locations (Gallagher, Burwell, & Burchinal, 1993). The CIPL value measures the cumulative distance over time from the escape platform corrected by an animal’s swimming velocity, and is equivalent to the cumulative search error described by Gallagher and colleagues (1993). Therefore, regardless of the release location, if the rat mostly swims towards the escape platform the CIPL value will be low. In contrast, the more time a rat spends swimming in directions away from the platform, the higher the CIPL value. After the visually-cued trials of the Morris swim test, eight aged rats and three young rats either did not find the platform within a minute, or had a CIPL value that was greater than two standard deviations from the group mean of the young rats and were therefore excluded from the experiment due to poor vision (data not shown). These animals did not participate any of the object recognition experiments.

Spontaneous object recognition testing procedures

Within two weeks of completing the Morris swim task procedures, each rat participated in one of three different behavioral experiments designed to evaluate stimulus recognition. The specific of details of each experiment are discussed below. The apparatus used for Experiments 1 and 2, and for the familiarization phase of Experiment 3 was a box constructed from wood, 30 cm by 30 cm, with walls that were 30 cm tall. All walls of the apparatus were painted black, and the floor was black with a grid that was used to ensure that the location of objects did not change between object familiarization and test phases. Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram of this testing apparatus. Due to the requirement for a change in context, an additional apparatus was used for the test phase of Experiment 3 (Figure 3; bottom arena). This testing box was located in a different room and was identical in size (30 cm × 30 cm × 30 cm) to the original apparatus but the walls were brown and the floor was grey. For both apparati, an overhead camera and a video recorder were used to monitor and record the animal’s behavior for subsequent analysis.

Figure 1. Schematic of the standard SOR testing used in Experiment 1.

The testing arena was 30 cm by 30 cm with 30 cm high walls and it was painted black. The floor had a grid painted on it to ensure that the object placement was consistent between the familiarization phase and the test phase and to help distinguish arena A from arena B (used in Experiment 3). The white cylinders indicate the location that the objects were placed in during the familiarization phase (top arena). The schematic white rat is shown in the orientation of when the rat is first placed in the arena. In the object familiarization phase (top arena), a rat is placed in the arena to explore duplicate copies of an object (A1 and A2). The rat is then moved from the arena for a variable delay (2 min, 15 min, 2 hr, or 24 hr). Following the delay, during the test phase (bottom arena), the animal is returned to the arena to explore a triplicate copy of the objects presented during the familiarization phase (A3) and a novel object (B1).

Figure 3. Schematic of the SOR task with context change (Experiment 3).

In the object familiarization phase, duplicate copies of an object (e.g., F1 and F2) were presented to the rat, which was then allowed a total of 4 min of exploration in the open arena. After the familiarization phase, and a 2 min or a 24 hour delay, the rat was relocated to a different room that contained arena B. During the test phase in arena B, the two objects were placed in similar locations relative to the walls of the apparatus as in the familiarization phase and the rat was allowed 4 min of exploration. During the test phase, one object (F3) was the third copy of the triplicate set of the objects used in the familiarization phase, and the other was a novel object (G1).

In all three experiments, the episodes of exploration were videotaped for offline analysis, with “exploratory behavior” defined as the animal directing its nose toward the object at a distance of ~2 cm or less (Ennaceur & Delacour, 1988). Any other behavior, such as resting against the object, or rearing on the object was not considered to be exploration. Exploration was scored by an observer blind to the rat’s age and the duration of the delay between the object familiarization and the test phases. Additionally, the amount of time spent exploring objects during the test phase was scored prior to measuring the amount of exploration during the object familiarization phase. This reverse-order of analysis ensured that the scorer was blind with respect to which object was familiar and which object was novel. Finally, the positions of the objects in the test phases, and the objects used as novel or familiar, were counterbalanced between the young and the aged animals in all three experiments.

Experiment 1: Standard spontaneous object recognition (SOR) testing

Stimulus recognition was measured in 16 young (7–9 months) and 18 aged (24–25 months) male F344 rats using the standard version of the spontaneous object recognition (SOR) task. Before testing began, all rats were exposed to the empty apparatus (Figure 1) for 10 minutes on two consecutive days. Recognition testing began the day immediately following this habitation procedure.

There are two components or “phases” of SOR testing: “object familiarization” and “test” phases. All rats participated in four object familiarization and test phases with 4 different delays (2 min, 15 min, 2 hours and 24 hours) between familiarization and test. Each rat participated in every delay condition once. The order of the delays and were pseudorandomized individually for every rat. The stimuli presented were triplicate copies of objects made of glass, plastic or wood that varied in shape, color, and size. Therefore, different sets of objects were texturally and visually unique. All rats were exposed to the same stimulus sets for a single delay condition. In the object familiarization phase, duplicate copies of an object (Figure 1; A1 and A2) were placed as shown in Figure 1 (10 cm from each adjacent wall). The white cylinders and the grey pyramid in Figure 1 indicate the positions of the objects for both phases of recognition testing. The animal was placed into the arena facing the center of the wall opposite to the objects (Figure 1; schematic white rat). The rat was then allowed a total of 4 min of exploration in the open arena. After the object familiarization phase, delays were imposed before exposure to the box in the test phase. For the 2 minute delay, the rat was placed in a covered pot next to the apparatus. This prevented the animal from being exposed to extraneous visual stimuli. For the 15 min, 2 hr, and 24 hr delays, the rat was returned to its cage in the colony room. Rats were placed in covered pots for all transportation between the colony room and the experimental apparatus.

During the test phase (bottom arena), the animal was returned to the apparatus and placed back into the same start location as for the object familiarization phase (Figure 1; schematic white rat). Again, the rat was allowed 4 min of exploration but was presented with two different objects than had been used during the familiarization phase. One object (Figure 1; A3) was the third copy of the triplicate set of the objects used in the object familiarization phase (familiar), and the other was a novel object (Figure 1; B1). The white cylinder and grey pyramid in the bottom box of Figure 1 represent the location of the objects during the test phase. All objects and the apparatus were washed with 70% ethanol between every trial and before procedures began with another rat.

Different sets of objects were used for each delay condition, and each object was trial-unique. Additionally, each rat only participated in one object familiarization/testing procedure per day. It was observed that rats habituate quickly to the objects, even when novel, and performing more than one testing session per day leads to reductions in overall exploration.

The difference in time spent exploring the novel object compared with the familiar object divided by the time spent exploring both objects was calculated to obtain the “discrimination ratio” (Dix and Aggleton, 1999). Additionally, the absolute time spent exploring the individual familiar or novel objects was compared between age groups.

Experiment 2: Novel/repeat spontaneous object recognition testing

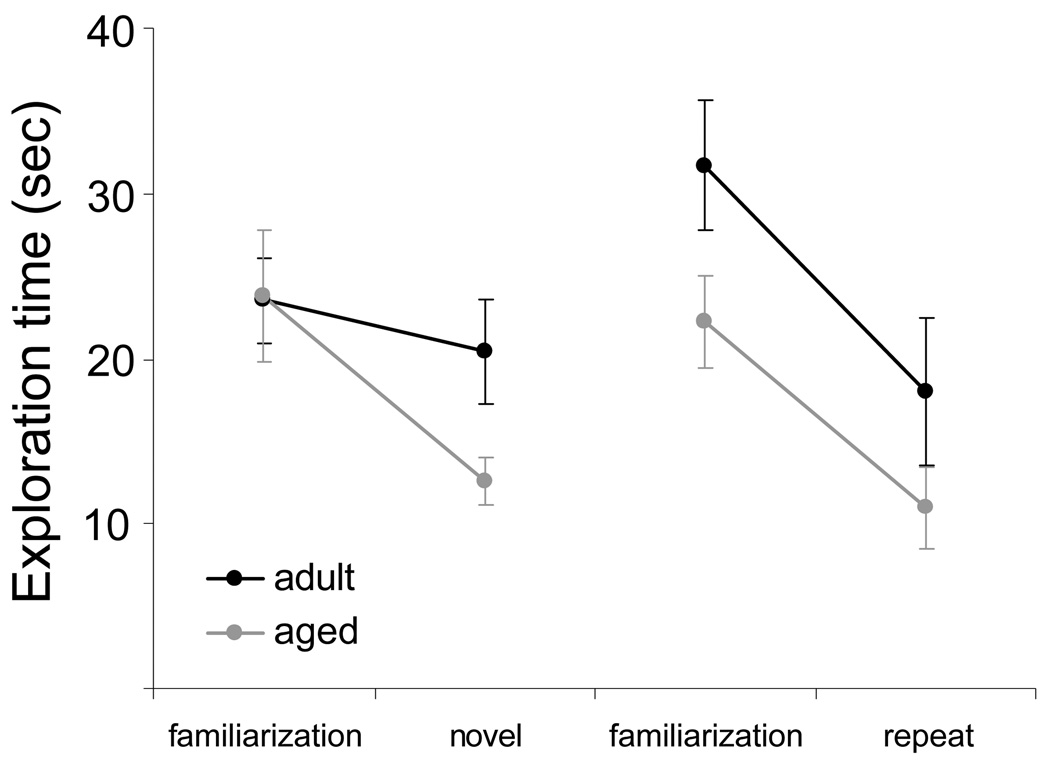

Object recognition was also tested using a variant of the spontaneous object recognition task that simultaneously presents two identical novel objects during the familiarization phase, but during the test phase either two different novel objects (“novel” condition) are presented, or the objects from the familiarization phase are presented again ("repeat" condition; McTighe et al., 2008). A total of 10 young (7–9 months old) and 10 aged (24–25 months) F344 rats participated in this behavioral experiment.

Rats were habituated to the testing apparatus for 10 minutes per day over two consecutive days, and recognition testing began the day immediately following the final habituation episode. Each rat performed two trials of recognition testing. One trial was the repeat condition while the other was the novel condition. The order of the trials and the stimuli presented were counterbalanced across age groups. The stimuli presented were duplicate copies of objects, and for both trials the object familiarization and test phases were separated by a 2 hr delay. In the first familiarization phase, duplicate copies of an object (e.g., C1 and C2) were placed near the two corners at either end of one side of the arena (10 cm from each adjacent wall). The animal was placed into the arena facing the center of the opposite wall (Figure 2; schematic white rat), and then the rat was allowed a total of 4 min to explore in the open arena. After this object familiarization phase, the rat was returned to its home cage in the colony room for the 2 hr delay. After the delay, the rat was returned to the same testing apparatus. For half of the young and old rats, two objects that were identical to the objects from the familiarization phase were again placed in the testing arena at the same locations (C3 and C4; repeat condition). For the other 5 young and 5 aged rats, two identical novel objects (D1 and D2; novel condition) were placed in the arena in the same location as the objects from the familiarization phase. In both cases, the rats were given 4 min to explore. After the test phase, the rat was returned to the colony room for 24 hours before participating in another familiarization phase.

Figure 2. A schematic of the presentation of objects used in novel/repeat SOR task (Experiment 2).

Experiment 2 consisted of familiarization phase 1 followed by a two hr delay and then test phase 1. The next day, rats participated in a familiarization phase 2, which was again followed by a 2 hr delay and test phase 2. During the first familiarization phase, duplicate copies of an object (e.g., C1 and C2) were presented and the rat was allowed a total of 4 min of exploration in the open arena. After a 2 hour delay, the rat was returned to the same testing apparatus. For half of the young and the aged rats the same two objects from the familiarization phase were again placed in the testing arena in the same location (C1’ and C2’; repeat condition). For the other 5 young and 5 aged rats two identical novel objects (D1 and D2; novel condition) were placed in the arena in the same location as the objects from the familiarization phase. In both cases, the rats were given 4 min to explore. After the test phase, the rat was returned to the colony room for 24 hours before performing another object familiarization phase. During this second object familiarization phase, the rat was given 4 min to explore two identical novel objects that were distinct from any of the objects used the previous day (E1 and E2) and in a different position within the apparatus. After a 2 hour delay, the rats that had participated in the repeat condition on previous day were exposed to the two novel objects that they had not been presented with (D1 and D2; novel condition). Conversely, the 5 adult and the 5 aged rats that were given a novel presentation on the previous day were exposed to the same objects from the object familiarization phase (E1’ and E2’; repeat condition).

The second trial of recognition testing occurred 24 hours after the first trial. During the familiarization phase of this trial, all rats were given 4 min to explore two identical novel objects that were distinct from any of the objects used the previous day (E1 and E2). Additionally, the position of the objects in the arena was also changed (Figure 2; left panels) in order to help promote more exploration (Cavoy & Delacour, 1993). After this object familiarization phase, the rat was returned to its home cage in the colony room for the 2 hr delay. After this delay, the rats that had participated in the repeat condition on the previous day were exposed to the two novel objects that they had not been presented with (D1 and D2; novel condition). Conversely, the 5 young and the 5 aged rats that were given a novel presentation for the test phase on the previous day were exposed to objects that were identical to those from the familiarization phase (E3 and E4; repeat condition). Therefore, all rats performed 1 repeat condition and one novel condition with a 2 hr delay, and the design was counterbalanced to control for order effects. Figure 2 shows a schematic representation of the novel/repeat SOR testing procedure used in Experiment 2.

In Experiment 2 the objects and their relative novelty were always identical within a phase, therefore, it was not possible to calculate a discrimination ratio. Thus, all comparisons between age groups and condition (repeated versus novel) were made using total exploration time.

Experiment 3: Spontaneous object recognition testing with context change

The effect of an incongruent context between the object familiarization and the test phase of the spontaneous object recognition task was measured in 15 young (9 months) and 15 aged (24 months) F344 rats. The procedures used in Experiment 3 were similar to those in Experiment 1. Before testing began, rats were exposed to arena A (Figure 3; top box) for 10 minutes and then returned to their home cage in the colony room for several hours. After this rest period, the rat was then exposed to arena B (Figure 3; bottom box) for 10 minutes. This habituation procedure occurred on two consecutive days, and was followed on the third day by the object recognition experiment. Arena A was used for both familiarization phases, while the two testing sessions always occurred in arena B.

Each rat participated in two object familiarization and test phases with delays of 2 minutes and 24 hours between the familiarization phase and the test phase. The stimuli used were triplicate copies of objects. In the familiarization phase, duplicate copies of an object (e.g., F1 and F2) were placed 10 cm from each adjacent wall. The two green cubes in Figure 3 indicate the positions of the objects for the familiarization phase of recognition testing. The animal was placed into the arena facing the center of the wall opposite to the objects (Figure 3; schematic white rat), and then allowed a total of 4 min of exploration in the open arena. After this object familiarization phase, for the 2 minute delay, the rat was relocated, in a covered pot, to a different room that contained arena B and then the test phase was administered in arena B. For the 24 hr delay the rat was immediately returned to its home cage in the colony room after the familiarization phase. After the 24 hr delay, the rat was taken from the colony room and transferred to arena B for testing in a covered pot to minimize extraneous visual cues.

During the test phase in arena B, the two objects were placed in similar locations relative to the walls of the apparatus as in the familiarization phase. These two locations are marked by the green cube and the blue cross in Figure 3. Additionally, the rat was placed in arena B at a similar start location relative to the walls and objects as was used during the object familiarization phase in arena A (Figure 3; schematic white rat). The rat was allowed 4 min of exploration in arena B with two different objects than had been used during acquisition. One object (F3) was the third copy of the triplicate set of the objects used in the familiarization phase (familiar), and the other was a novel object (G1). Figure 3 shows the object presentation procedures used for Experiment 3. All objects and the testing apparatus were washed with 70% ethanol between every trial and before procedures began with another rat. The difference in time exploring the novel object compared with the familiar object divided by the time spent exploring both objects was calculated (discrimination ratio; Dix and Aggleton, 1999). Additionally, the amount of time rats spent exploring individual objects during the test phase was compared between age groups.

Data analysis for experiments 1, 2 and 3

Data from the three different experiments were analyzed separately. In Experiments 1 and 3, group means of four measures (the total time spent exploring objects during the familiarization phase, the discrimination ratio, the time spent exploring the novel object during the test phase, and the time spent exploring the familiar object during the test phase) were examined using repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). The within-subjects factor of delay duration and the between-subjects factor of age group were the independent variables. For Experiment 2 the within-subjects factor of experimental condition (repeat versus novel), the between-subjects factor of age group on the total time spent exploring objects during the familiarization phase, and total time spent exploring objects during the test phase were analyzed with repeated-measures ANOVA. All statistical tests and p-values were calculated using SPSS 9.0 (Chicago, Illinois) and alpha was set at the 0.05 level. When the F statistic reached statistical significance, tests for individual group differences using either the post hoc Tukey HSD test or, if there was a specific hypothesis regarding the group differences, planned orthogonal contrasts (repeated contrast) were made.

Results

Morris swim task performance

The mean performance of the aged rats on the spatial version of the Morris swim task was significantly worse than the performance of the young rats. Every aged rat that participated in recognition testing was able to learn the visual version of the task, however. Figure 4A shows the mean CIPL (Gallagher et al., 1993) for the forty-three aged rats (grey circles), and the forty-one young rats (black circles) that participated in these behavioral experiments. All animals were tested over 4 days with 6 spatial trials on each day. As reported previously (e.g., Barnes et al., 1997), the old rats had a significantly longer mean CIPL scores, compared with the young rats (F[1,312] = 86.98, p < 0.001; ANOVA). Post hoc analysis revealed that this difference was due to the aged rats having significantly longer CIPL scores on days 2, 3 and 4 of spatial testing (p < 0.001; for all comparisons; Tukey HSD) while there was no significant difference in the path lengths between young and aged rats on Day 1 of spatial testing (p = 0.99; Tukey HSD). The old rats, however, did show a significant improvement in finding the hidden platform between Day 1 and Day 4 of spatial testing (F[1,40] = 13.50, p < 0.01; repeated-measures ANOVA). This improvement did not differ significantly between the aged rats that participated in the three different experiments (F[2,40] = 2.52, p = 0.1; repeated-measures ANOVA), indicating that the groups of aged rats that participated in the three different experiments had comparable spatial learning impairments. Figure 4B shows the CIPL scores for the spatial trials on Day 4 of testing for individual rats. The horizontal black lines indicate the mean CIPL for each age group. The CIPL scores for 36 of the aged rats were more than 1 standard deviation above the mean score for the young animals. Only 7 aged rats had a CIPL score within 1 standard deviation of the young animals, and none of the young rats had a CIPL score that was within 1 standard deviation of the aged rat mean. For this reason, analyses of object recognition measures only compared the young rats to the aged rats because the small number of “spatially-unimpaired” aged rats did not provide adequate statistical power to further subdivide the aged group into impaired and unimpaired.

Figure 4. Morris swim task performance of young and aged rats.

(A) The X-axis is the day of testing and the Y-axis is the mean corrected integrated path length (CIPL) score. Higher CIPL scores indicate longer path lengths to reach the escape platform. All rats completed 4 days of spatial trials (circles) in which the platform was hidden below the surface of the water. These spatial trials were followed by 2 days of visually-cued trials in which the platform was visible (triangles). During the spatial trials, the aged (purple) rats had significantly longer CIPL scores compared with the young (green) rats (F[1,312] = 86.98, p < 0.001; ANOVA). The performance of the aged rats, however, benefited significantly more when the escape platform was visible compared to the young rats (F[1,82] = 32.42, p < 0.001; repeated-measures ANOVA). Error bars represent +/−1 standard error of the mean. (B) The mean CIPL scores of individual young (green) and aged (purple) rats on Day 4 of spatial testing. The horizontal black lines indicate the mean CIPL for each age group. In the aged rats, CIPL score values below the grey horizontal line represent rats that performed within 1 standard deviation of the young animals. Only 7 aged rats met this criterion while the other 36 rats had CIPL scores that were at least 1 standard deviation above the young rat mean.

To test whether the spatial impairments of the aged rats were due to visual problems, and to ensure that all rats had adequate vision to participate in recognition testing, the rats also performed 12 trials (6 trials/day) on the visually-cued version of the Morris swim task. In this version of the task the platform is raised above the surface of the water, but its location changed every trial. Figure 4A shows the CIPL values for the visual trials of the Morris swim task for the trials on Day 1 and Day 2 for the aged (black triangles) and the young (grey triangles) animals. Both the aged and the young rats showed a significant decrease in the CIPL measure on the 2nd day compared with the first day (F[1,78] = 52.53, p < 0.001; repeated-measures ANOVA). There was a small effect of age group on the CIPL score for Day 2 of visual testing, with aged rats having significantly longer path lengths compared to the adult animals (T[82] = 2.52, p < 0.05; student’s T-test). This difference was less than 2 meters, and when the CIPL score from Day 4 of spatial testing was compared to the visual score from Day 2 it was observed that the performance of the aged rats benefited significantly more when the escape platform was visible compared to the young rats (F[1,82] = 32.42, p < 0.001; repeated-measures ANOVA). Moreover, there was no correlation between the visual trial CIPL scores on Day 2 of testing and the spatial trial CIPL scores on Day 4 of testing in old rats (r = −0.01, p = 0.9). This indicates that the rats that did worse on the spatial trials were not the rats with poorer vision and thus it is unlikely that the aged animals used for the current series of experiments were significantly visually impaired.

Experiment 1: standard SOR task results

Figure 1 shows a schematic of the standard SOR task that was used for Experiment 1. The young and the aged rats spent a comparable amount of time exploring the two identical objects during the familiarization phases (Table 1), as indicated by the lack of a significant main effect of age group on exploration time during the object familiarization phases (F[7,128] = 1.73, p = 0.11; ANOVA).

Table 1.

Exploration times during the familiarization phase of Experiment ± 1standard error of the mean

| 2 min | 15 min | 2 hr | 24 hr | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young | 41.2 sec ± 5.0 | 31.3 sec ± 5.5 | 43.0 sec ± 6.9 | 37.9 sec ± 9.4 |

| Aged | 36.8 sec ± 6.2 | 28.2 sec ± 4.2 | 36.5 sec ± 4.8 | 19.6 sec ± 3.9 |

When discrimination ratios were calculated from the time spent exploring the novel versus familiar object during the test phase, the aged rats had significantly lower discrimination ratios compared to the young animals (F[7,128] = 7.26, p < 0.001; ANOVA). Planned comparisons revealed that the discrimination ratio was significantly less in the aged rats relative to the young rats for the 15 min, 2 hr, and 24 hr delays (p < 0.05 for all comparisons; repeated contrasts), but not the 2 min delay (p = 0.28, repeated contrast). This indicates that the aged rats were able to discriminate between the novel and familiar objects at short delays, and thus it is unlikely that the recognition impairments at the longer delays are due to age-associated vision, olfactory or somatosensory impairments. Additionally, changes in the general motivation to explore objects cannot account for the current results. Figure 5A shows the discrimination ratios of the adult (black) and aged rats (grey) during the test sessions for all delays. Although lower discrimination ratios are often interpreted as the animal ‘forgetting’ what object was encountered during the familiarization phase, a decrease in the discrimination ratio can occur either from increased exploration of the familiar object or reduced exploration of the novel object. Thus, the raw exploration times of the novel and familiar objects during the test phase were also compared between the two age groups.

Figure 5. SOR task performance (Experiment 1).

(A) The mean discrimination ratio of the adult (black) and the aged rats (grey) measured during the test phase for the four different delay conditions. A higher discrimination ratio indicates that the animal spent more time exploring the novel object relative to the familiar object. Overall, the aged rats had significantly smaller discrimination ratios when compared to the adult rats (F[7,128] = 7.26, p < 0.001; ANOVA). (B) The mean amount of time young (black) and aged (grey) rats spent exploring the familiar and the novel object during the test phase for the four different delay conditions. There was a significant main effect of novel versus familiar objects on exploration time (F[1,128] = 122.03, p < 0.001; repeated-measures ANOVA). Additionally, the interaction effect of age group (adult versus aged), and object (novel versus familiar) on exploration time during the test phase was significant (F[1,128] = 22.08, p < 0.001). Error bars represent +/−1 standard error of the mean.

Analysis of the raw exploration times of individual objects, during the test phase, showed that the age-associated reduction in the discrimination ratio at the 15 min, 2 hr, and 24 hr delays was associated with a reduction in novel object exploration in the aged compared to the young rats. In contrast, the amount of time spent exploring the familiar objects was similar in both age groups. Figure 5B shows the mean time spent exploring the novel and familiar objects for the young (black), and aged rats (grey) for all four delay conditions. There was a significant main effect of novel versus familiar objects on exploration time (F[1,128] = 122.03, p < 0.001; repeated-measures ANOVA). Additionally, the interaction effect of age group, and object familiarity (novel versus familiar) on exploration time during the test phase was also statistically significant (F[1,128] = 22.08, p < 0.001). Planned contrasts comparing the exploration times of the novel object between the young and the aged rats revealed that this interaction effect was due to a significant reduction in the old rats’ exploration of novel objects for the 15 min, 2 hr and the 24 hr delay conditions (p < 0.01 for all comparisons; repeated contrasts), but not the 2 min delay (p = 0.48; repeated contrast). In contrast to the novel objects, there were no significant differences in the time spent exploring familiar objects in the test phase between the young and the aged rats during any delay (p > 0.1 for all comparisons; repeated contrast). These data suggest that the age-associated reduction in the discrimination ratio at delays greater than 2 min selectively results from the aged rats exhibiting reduced exploration of the novel object. Because in the familiarization phase of the standard SOR task the two objects are identical, and both are novel, while during the test phase the objects are different and only one is novel it is difficult to compare the two phases directly. To get around the fact that the object familiarization phase and the test phase are distinguishable by both the relative familiarity of the objects and by the difference between the objects presented during the test phase, a variant of the SOR task was implemented that controls for these confounds, and this task was administered to an additional group of young and aged rats (McTighe et al., 2008).

Experiment 2: Novel/repeated SOR task results

Object recognition was tested in Experiment 2 by presenting identical objects during both the familiarization and the test phases (Figure 2). Ten adult and 10 aged rats participated in this variant of the SOR task with 2 hr delays between test and familiarization phases. This delay duration was selected because aged rats reliably show a decrease in the discrimination ratio after a two hour delay and this enabled the object familiarization phase and the test phase to occur on the same day. For details regarding testing procedures and counterbalancing see methods (Figure 2; McTighe et al., 2008).

Statistical analysis of the data obtained in Experiment 2 revealed that there was no significant main effect of age group on exploration time (F[1,18] = 1.33, p = 0.26; ANOVA). Additionally, there was no significant difference in total exploration time between the first object familiarization phase and the second familiarization phase on the subsequent (F[1,18] = 1.64, p = 0.22). Table 2 shows the exploration times during the familiarization phases for the young and the aged rats. Additionally, there was no significant difference in total exploration time between the first object familiarization phase and the second familiarization phase on the subsequent day in either age group (F[1,18] = 1.64, p = 0.22). This could be due to the objects being in different locations between the first and the second familiarization phases. Furthermore, there was no significant interaction between age group and exploration time during the first and second object familiarization phases (F[1,18] = 1.77, p = 0.20).

Table 2.

Exploration times during the familiarization phase of Experiment 2 ± 1standard error of the mean

| Novel condition |

Repeat condition |

|

|---|---|---|

| Young | 23.5 sec ± 2.6 | 31.7 sec ± 3.9 |

| Aged | 23.8 sec ± 4.0 | 22.2 sec ± 2.5 |

Figure 6 shows the total mean time spent exploring objects by young (black) and aged (grey) rats during both the familiarization and the test phases for the novel and the repeat conditions. Statistical analysis revealed that there was a significant main effect of experimental phase (object familiarization versus test) on total exploration time (F[1,36] = 69.45, p < 0.001), with more object exploration occurring during the familiarization phase compared to the test phases. There was also a significant interaction effect between experimental phase and condition (novel versus repeat) on exploration time (F[1,36] = 5.03, p < 0.05), and a significant three-way interaction effect of age group, experimental phase, and condition (F[1,36] = 5.86, p < 0.05). Post hoc analysis revealed that these interaction effects resulted from a significant decrease in exploration time between the object familiarization and the test phase for the young rats during the repeat condition but not during the novel condition (p < 0.02; Tukey HSD). Specifically, the young group of animals spent similar amounts of time exploring objects between the familiarization and test phases if the objects were novel in both episodes (novel condition). If, however, the objects presented during the familiarization phase were presented again during the test phase (repeat condition), the young rats explored them less relative to their first presentation. In contrast, the aged rats always explored the objects less during the test phase relative to the familiarization phase regardless of whether the objects were novel or repeated during the test phase (p < 0.05 for both comparisons; Tukey HSD). These data support the idea that after long delays between familiarization and test phases, the aged rats may identify novel objects as familiar. These data do not support the idea that aged rats do not remember the previously experienced objects.

Figure 6. Novel/repeat SOR task performance (Experiment 2).

The mean exploration time of the adult (black) and the aged rats (grey) measured during all four episodes of exploration. In the young rats, there was only a significant reduction in the total exploration time when the object presentation was the same between both the familiarization and the test phases (repeat condition; p < 0.02; Tukey HSD). In contrast, the aged rats showed a reduction in total exploration time between the familiarization and test phases both when the object presentation was repeated and when it was novel (p < 0.05; Tukey HSD). Error bars are +/−1 SEM.

An alternative explanation for the results observed in Experiment 2 is that the aged rats habituate to object exploration and will explore less during the test phase regardless of whether the objects are familiar or novel. To rule out this possibility, young and aged rats were tested on an object recognition task with incongruent contexts between the familiarization and test phases. This procedure was expected to elicit increased exploration of both novel and familiar objects during the test phase (Eacott & Norman, 2004; Norman & Eacott, 2005).

Experiment 3: SOR task with context change

Figure 3 shows a schematic of the SOR task with context change. Table 3 shows the total time in seconds that rats spent exploring the objects during the familiarization phase (arena A) for the 2 min, and the 24 hr delays. Unlike Experiments 1 and 2, there was a main effect of age group (young versus old) on total exploration time during the familiarization phase. Post hoc analysis revealed that the young rats spent more time exploring objects during the familiarization phase that preceded the 2 min delay compared to the aged rats (p < 0.05; Tukey HSD), but the young and old rats explored the objects a similar amount of time during the object familiarization phase that occurred before the 24 hr delay (p = 0.85; Tukey HSD).

Table 3.

Exploration times during the familiarization phase of Experiment 3 ± 1standard error of the mean

| 2 min | 24 hr | |

|---|---|---|

| Young | 30.1 sec ± 2.2 | 20.3 sec ± 1.9 |

| Aged | 21.3 sec ± 1.9 | 18.1 sec ± 1.8 |

Because it has been shown that objects become bound to the context that they were experienced in (e.g., Hayes, Nadel, & Ryan, 2007; Piterkin, Cole, Cossette, Gaskin, & Mumby, 2008), rats will express exploratory behavior as if a previously experienced object is novel when the object is presented in a different context from where it was first experienced (Eacott & Gaffan, 2005; Eacott & Norman, 2004; Norman & Eacott, 2005). Therefore, by measuring object recognition when the context is different between the familiarization and the test phase, we can assess whether aged rats show an overall habituation to object exploration or if they incorrectly indentify novel objects as being familiar. Specifically, if the context changes and aged rats still show reduced exploration to both novel and familiar objects, then it is likely that the reduced exploration results from old animals habituating to object exploration in general. In contrast, if the aged rats explore both novel and familiar objects more in a new context, then this would indicate that the reduced novel object exploration observed during Experiments 1 and 2 is because aged rats were impaired at identifying a new object as novel after long delays.

Figure 7A shows the discrimination ratios measured during the test phases (arena B) of both delay conditions in the young and aged rats. When the context was changed between the object familiarization and test phases, there was no effect of age on the magnitude of the discrimination ratio (F[1,28] = 0.06, p = 0.81). This result is clearly distinct from those obtained in the standard SOR task used in Experiment 1, where a reduction in the discrimination ratio was found in aged rats relative to young rats at delays longer than 2 min. This suggests that the aged and the young rats are affected similarly by incongruent contexts. There was a main effect of delay duration (2 min versus 24 hr), such that the discrimination ratio during the test phase (in arena B) was significantly larger for the 2 min compared to the 24 hr delay condition (F[1,28] = 11.08, p < 0.005; repeated-measures ANOVA). This occurred in both the young and the aged rats as the interaction effect between age group and delay condition was not significant (F[1,28] = 0.29, p = 0.60; repeated-measures ANOVA). Moreover, the discrimination ratio following the 24 hr delay was not significantly different between the young and the aged rats (T[28] = 0.55, p = 0.59; independent-samples T test). Importantly, when the discrimination ratio for the 24 hr delay is compared between the young rats that participated in the standard SOR task and the young rats that participated the SOR task with context change, the discrimination ratio was significantly smaller during the context change condition (T[29] = 2.29, p < 0.03; independent-samples T test). In fact, when the context changed, the discrimination ratio following the 24 hr delay was not significantly different from zero in either the young (T[14] = 0.50, p = 0.63), or the aged rats (T[14] = 0.22, p = 0.83). These data support the idea that although objects become bound to the context in which they were experienced (Hayes et al., 2007), this binding requires time (>2 min). Thus, when more time passes a rat will behave as if a familiar object is novel when it is encountered in a different context. This idea was confirmed when the total exploration times of the novel and familiar objects were compared (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. SOR task with context change task performance (Experiment 3).

(A) The mean discrimination ratio of the young (black) and the aged rats (grey) measured during the test phase, in arena B, for the 2 min and 24 hour delay conditions. A higher discrimination ratio indicates that the animal spent more time exploring the novel object relative to the familiar object. Both the young and aged rats had a higher discrimination ratio after a 2 min delay compared to the 24 hour delay as indicated by the significant main effect of delay duration (F[1,28] = 11.08, p < 0.005; repeated-measures ANOVA). For the 24 hour delay, neither the young nor the aged rats distinguished between the novel and familiar object as indicated by the lack of a significant interaction effect between age group and delay condition (F[1,28] = 0.29, p = 0.60; repeated-measures ANOVA). (B) The mean amount of time young (black) and aged (grey) rats spent exploring the familiar and the novel object during the test phase for the 2 min and the 24 hour delay conditions. Unlike experiment 1, in which the context was congruent, when the context changed between the acquisition and the test phase, the adult and the aged rats spent significantly more time exploring the familiar objects for the 24 hr delay relative to the 2 min delay (p < 0.05; repeated contrasts). In contrast, the exploration time of the novel objects was not significantly different between delay conditions (p > 0.05 for all comparisons; Tukey HSD). Error bars represent +/−1 standard error of the mean.

Figure 7B shows the mean time spent exploring the novel and the familiar objects for the young (black), and aged rats (grey) for the 2 min and the 24 hr delay conditions. The analysis of object exploration times during the test phase in arena B showed that the reduction in the discrimination ratio at the 24 hr delay was associated with increased familiar object exploration in both the young and the aged rats. Specifically, there was a significant main effect of novel versus familiar objects on exploration time (F[1,56] = 5.97, p < 0.02; repeated-measures ANOVA). Additionally, the interaction effect of delay duration (2 min versus 24 hr), and object type (novel versus familiar) was significant (F[1,56] = 4.07, p < 0.05), but there was no significant main effect of age on exploration time (F[1,56] = 3.54, p = 0.07). Planned contrasts comparing the time spent exploring the familiar objects during the test phases for 2 min and the 24 hr delay conditions revealed that this interaction effect was due to a significant increase in the exploration time of the familiar object during the 24 hr delay relative to the 2 min delay in both the young and the aged rats (p < 0.05; repeated contrasts). The increased exploration of the familiar object after a 24 hr delay indicates that the reduced novel object exploration observed in aged rats for Experiments 1 and 2 is not due to the old animals showing an overall habituation to object exploration.

Finally, the amount of time spent exploring the novel object during the test phase was not significantly different between the 2 min and 24 hr delay conditions (p > 0.05 for all comparisons; Tukey HSD). The aged rats, however, explored the novel object significantly less compared to the young rats following a 2 min delay (p < 0.05, Tukey HSD). One explanation for the reduced novel object exploration after a 2 min delay and a context change is that by moving the old rat to a different room and testing arena, the animal is exposed to more stimuli that share features with the test objects. As in the standard SOR task with longer delays, these stimuli may interfere with the animal’s ability to identify the new object as novel.

Relationship between object recognition and spatial memory

In Experiment 1, the discrimination ratios after the 2 min and 15 min delays (r[33] = 0.34, p < 0.05; Pearson’s correlation coefficient) and the ratios after the 15 min and 2 hour delays (r[33] = 0.35, p < 0.05; Pearson’s correlation coefficient) were significantly correlated. In contrast, the 24 hour delay discrimination ratio was not correlated with any other delay (r < 0.15, p > 0.39 for all comparisons; Pearson’s correlation coefficient). The observation that rats with better object recognition at the 2 min delay also had better performance at the 15 min delay, and that discrimination ratios were similar following the 15 min and 2 hr delays suggests that there was sufficient test-retest reliability on the SOR task to justify a comparison between object recognition and Morris swim task performance. Figure 4B shows the individual CIPL scores on Day 4 of spatial swim task testing for the young and the aged rats. Of the 18 aged rats that participated in Experiment 1, only 3 showed performance levels on the spatial version of the Morris swim task within 1 standard deviation of the mean performance of the young rats. The performance of this group of spatially ‘unimpaired’ rats on the SOR task, at all delay durations, was not significantly different from the rats that performed more than 1 standard deviation above the mean of the young animals on the spatial version of the Morris swim task (F[2,16] = 1.06, p = 0.37; ANOVA). Additionally, when z-scores were calculated from the CIPL values on Day 4 of spatial testing for aged and adult rats separately, no significant relationship was found between spatial memory and object recognition in either age group for the 2 min (F[1,31] = 0.69, p = 0.41; linear regression), 15 min (F[1,31] = 0.55, p = 0.46; linear regression), 2 hr (F[1,31] = 1.34, p = 0.26; linear regression), or the 24 hr delays (F[1,31] = 0.25, p = 0.62; linear regression). Similarly, in Experiment 2, three aged rats performed within 1 standard deviation of the young rats on the Morris swim task. The performance of these rats on the simultaneous novel/repeat SOR task was also not significantly different than the aged rats with worse spatial memory performance (F[2,8] = 0.80, p = 0.49; ANOVA). This supports the idea that the aging process affects different regions of the brain independently.

In Experiment 3, only 1 aged rat performed within 1 standard deviation of the young animals on the spatial version of the Morris swim task, which made a comparison between spatially impaired and spatially unimpaired animals untenable. Although novelty discrimination across incongruent contexts requires the hippocampus under some circumstances (O'Brien et al., 2006), there was no significant relationship between object recognition in Experiment 3 and Morris swim task performance in either the young or the aged rats at the 2 min delay (F[2,27] = 1.29, p = 0.29; linear regression) or the 24 hr delay (F[2,27] = 0.15, p = 0.87; linear regression).

Discussion

A number of important insights were gained from experiments conducted here concerning the nature of age-dependent changes in stimulus recognition. First, consistent with previous reports, aged rats show good recognition at short delays in the standard spontaneous object recognition (SOR) task, but poorer performance at longer delays when a “discrimination ratio” measure was used (Figure 5A; de Lima et al., 2005; Pieta Dias et al., 2007; Pitsikas et al., 2005; Pitsikas & Sakellaridis, 2007; Platano, Fattoretti, Balietti, Bertoni-Freddari, & Aicardi, 2008; Vannucchi et al., 1997). When a simple measure of total exploration time was examined, the reason the discrimination ratio was reduced in old rats during the test phase was because the older animals spent significantly less time exploring the novel object at delays greater than 2 min. Rather than the old rats showing increased ‘forgetting’ of the familiar objects, these data indicate that old animals behave as if novel objects are familiar at delays greater than 2 min. This hypothesis was confirmed by the results of Experiment 2, which enabled a direct comparison of the object exploration times in the familiarization and test phases. When 2 identical novel objects were presented during the familiarization phase, and then 2 different identical novel objects were presented during the test phase, only the young rats showed similar amounts of object exploration during both exposures to the novel objects. In contrast, the aged rats showed a significant attenuation in the time spent exploring novel objects between the familiarization and test phases. Finally, to measure whether or not the aged rats showed an overall habituation to object exploration, a final control experiment was conducted, in which the context was changed between the object familiarization and test phases. After a 24 hr delay, both young and aged rats behaved as if a familiar object was novel when it was presented in a different context. Because a change in context can elicit increased exploration in both age groups, it is not likely that the results obtained in Experiments 1 and 2 are due to an overall decline in aged rats’ motivation to explore.

Taken together, the current data suggest that the primary age-related deficit in object recognition at longer delays arises from old rats behaving during the test phase as if the novel object is familiar rather than from forgetting. Because reduced novel object exploration is not observed in aged rats after short delays and when objects are first encountered during the familiarization phase, it is possible that this age-associated deficit is due to the intervening stimuli encountered during long delay periods. Specifically, the 2 min delay of standard SOR task is the only condition in which the rats remained in a covered pot in the same room as the testing arena for the delay. Therefore, in this condition the amount of extraneous stimuli that the rat encountered before the test phase was reduced relative to the other conditions. This suggests that aged rats have been influenced by stimuli that are spontaneously encountered during longer delay periods. Conceivably some of these extraneous stimuli share common features with the objects presented during the test phase. Because old animals may be less able to discriminate different stimuli that share common features, the aged rats identify the novel object as familiar. Therefore, one could predict that if an aged rat was exposed to more stimuli during the 2 min delay period, then novel objects would be identified as familiar even at this short delay. In fact, this was observed. During Experiment 3, all of the rats were moved from the room containing arena A, after the familiarization phase, to a different room containing arena B for the test phase. In this experiment the aged rats did show less exploration of the novel object relative to the young rats.

Another possibility that might explain the observed age-related changes in object recognition are age-related changes in vision or differences in encoding during the object familiarization phase. The former is unlikely because all animals were screened for visual ability using the visually-cued Morris swim task, and rats that could not successfully find the visible platform were excluded from these experiments. Moreover, both age groups significantly benefitted from the platform being visible and showed shorter path lengths during visual trials relative to the hidden spatial trials. It is still possible, however, that the visually-cued Morris swim task was not sensitive enough to detect vision problems that could disrupt object recognition but leave swim task performance intact. This possibility also appears to be unlikely since the aged rats showed novelty discrimination comparable to the adult rats at the 2 min delay of the SOR task (Experiment 1).

Additionally, it is not likely that the observed age effect on object recognition is due to encoding differences during the object familiarization phase. During the standard SOR task (Experiment 1) adult and aged rats spent a similar amount of time exploring objects during the familiarization phase for the 2 min, 15 min, and 2 hr delays (Table 1). The aged rats did explore the objects less during the familiarization procedure for the 24 hr delay but since the age-associated reduction in novelty discrimination appeared at the 15 min and the 2 hr delays it is unlikely that changes in behavior during the familiarization phase could account fully for the current results. Moreover, there were no differences in exploratory behavior between age groups during the familiarization phases of Experiment 2 (novel/repeat object recognition; Table 2), even though there was a significant effect of age on exploratory behavior during the test phase.

Importantly, the current data indicate that novelty detection in aged animals is similar to that of young animals under some circumstances. Specifically, the aged rats showed similar amounts of exploration relative to the younger animals when two novel objects were presented during the familiarization phases in all three experiments. One explanation for this observation is that during the object familiarization phase, novel objects appear in a familiar context (arena A), previously devoid of stimuli. Under these circumstances an overall increase in arousal coupled with an orienting response to new salient features added to a familiar environment could elicit exploratory behavior in the aged rats that is comparable to the younger animals. In this view, aged animals have an increased threshold for detecting novelty because novel items often share features with familiar stimuli. Data from Experiment 3 also support this idea. Unlike in Experiments 1 and 2, where discrimination ratios decreased because the aged animals spent less time exploring the novel stimuli, in Experiment 3 when the context in which an object was explored is changed between the familiarization and test phases, the discrimination ratio decreased after a 24 hour delay because the rats explored the familiar object more.

Taken together, the current data call into question previous interpretations that impairments in object recognition in aged animals result from a decline in “memory”. The finding that the aged rats identify novel objects in the test phase as familiar requires an alternate explanation for age-associated stimulus recognition deficits. In fact, the behavior of old rats on the SOR tasks are consistent with data obtained from rats with perirhinal cortex lesions (McTighe et al., 2008). The perirhinal cortex is necessary for an animal’s ability to discriminate between stimuli that share common features (Barense, Gaffan, & Graham, 2007; Bartko, Winters, Cowell, Saksida, & Bussey, 2007b; Bussey, Saksida, & Murray, 2002, 2003). If the functional integrity of the perirhinal cortex is compromised during normal aging, aged rats may be impaired at disambiguating the novel objects presented during the test phase from other stimuli that were encountered during longer delays. Because the perirhinal cortex receives a direct projection from the ventral tegmental area (Furtak, Wei, Agster, & Burwell, 2007), it is also possible that an age-associated decline in mesolimbic dopamine activity contributes to the current observations.

The aged rats used in the current experiments also showed significant impairments on the hippocampal-dependent spatial version of the Morris swim task. It is unlikely, however, that age-associated changes in the hippocampus contributed significantly to the object recognition deficits observed in these experiments. First, although some studies have reported impairments on the SOR task in young rats with hippocampal lesions (e.g., Broadbent, Squire, & Clark, 2004). Other experiments have not observed an effect of hippocampal damage (e.g., Ainge et al., 2006; Forwood et al., 2005; Mumby, 2001; Winters et al., 2004). In fact, it appears that the object recognition impairments following hippocampal damage result from the lesioned animals spending less time exploring objects during the familiarization phase relative to the control rats. This deficit could therefore reflect encoding differences rather than a critical role for the hippocampus in object recognition (Ainge et al., 2006). Finally, there was no significant relationship between performance on the hippocampal-dependent spatial version of the Morris swim task and object recognition at any delay in either the young or the aged rats. This provides additional evidence that the hippocampus is not required for the recognition of objects.

The perceptual-mnemonic feature conjunctive (PMFC) model of the perirhinal cortex and object recognition during aging

Although it cannot be disputed that the perirhinal cortex is involved in object recognition (e.g., Buffalo et al., 1999; Buffalo, Ramus, Squire, & Zola, 2000; Ennaceur & Aggleton, 1997; Malkova et al., 2001; Norman & Eacott, 2005; Wiig & Burwell, 1998), whether or not this structure supports the recognition of stimuli via contributions to perception or as part of a ‘memory system’ has is still debated (e.g., Buckley & Gaffan, 2006; Cate & Kohler, 2006). This argument may not be productive, however, as there may be no anatomical locus where perception ends and memory begins (Gaffan, 2002). In fact, it has been suggested that the primary function of the perirhinal cortex is to bind together features represented in lower sensory cortices (Bussey, Saksida, & Murray, 2005; Murray, Bussey, & Saksida, 2007). Since the binding of information represented across disparate areas of the neocortex is believed to be the cornerstone of memory (McClelland, McNaughton, & O'Reilly, 1995; Teyler & DiScenna, 1986; Teyler & Rudy, 2007), perirhinal cortex lesions can lead to memory impairments. More recent lesions studies in humans (Barense et al., 2007), monkeys (Bussey et al., 2002), and rats (Bartko, Winters, Cowell, Saksida, & Bussey, 2007a; Bartko et al., 2007b), however, show that the perirhinal cortex is also necessary for visual discrimination when the items to be discriminated contain overlapping features so that correct discrimination cannot be based on a single feature alone. The idea that the perirhinal cortex is necessary for perception when a task requires judgments based on multiple stimulus features has been formalized by the perceptual-mnemonic feature conjunctive (PMFC) model. This model contends that the perirhinal cortex is required for the complex conjunction of stimulus features that are represented in lower sensory cortices (Murray & Bussey, 1999).

In the current experiment the stimuli used to test object recognition did not contain overlapping features, and the aged rats still did not discriminate between the novel and familiar objects. Under the framework of the PMFC model, this behavioral deficit in the aged rats could be explained by the greater amount of interfering stimuli that occurs during longer delays. When the delay between the familiarization and the test phase is short, and the old animal remains in a covered pot to reduce sensory input, aged rats show normal stimulus recognition. During a long delay between the familiarization and test phases, the rat encounters numerous stimuli containing simple features that are common to the objects presented during the SOR task. The specific conjunction of features that comprises a given complex object is unique, however. Therefore, over the course of the delay, interference can disrupt the representation of a unique object if the perirhinal cortex cannot adequately associate the unique configuration of the stimulus elements (that is, pattern separate; Marr, 1971). Thus, an animal with an intact perirhinal cortex has an advantage over an animal with damage to this region because it can associate the unique conjunctions of stimulus features making it easier to disambiguate between novel and familiar stimuli that share common elements. In contrast, an animal with a compromised perirhinal cortex may rely on the spared representations of individual stimulus features in lower visual cortical areas in order to discriminate between the novel and familiar stimuli. The object recognition impairment in animals with perirhinal cortex damage is exacerbated by longer delay conditions because this allows for more interference of common stimulus features (Cowell, Bussey, & Saksida, 2006). Therefore, animals with perirhinal cortical damage will incorrectly identify a novel stimulus as familiar. This has been reported for rats with perirhinal cortical lesions (McTighe et al., 2008), and was observed in the current study with aged rats. Importantly, it has also been shown that aged humans are impaired in visual recognition tasks when inferring stimuli share features with test stimuli (Toner, Pirogovsky, Kirwan, & Gilbert, 2009). This lends support to the idea that in advanced age there is a deficit in pattern separation that contributes to impairments in stimulus recognition.

6.4.3 Mesolimbic dopamine and novelty detection

The perirhinal cortex receives a direct projection from the basal ganglia, including the ventral tegmental area (Furtak et al., 2007) and sends a reciprocal projection back to the ventral striatum (McIntyre, Kelly, & Staines, 1996). Moreover, in adult humans (Bunzeck & Duzel, 2006), and monkeys (Schultz, 1998) novel visual stimuli are associated with an increase in ventral tegmental activity. Therefore, a ventral tegmental to perirhinal cortex projection could act to modulate cell activity in the perirhinal cortex in a way that facilitates the discrimination of novel objects from stimuli that have been previously encountered.

During aging, there are several changes in the limbic dopamine system (for review, see Barili, De Carolis, Zaccheo, & Amenta, 1998). Additionally, in aged humans reductions in mesolimbic hemodynamic responses to novelty correlate with volumetric reductions of the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area (Bunzeck et al., 2007). Finally, aged monkeys show a reduced novelty preference, relative to young monkeys, during the visual paired comparison task as measured by their eye movements to view novel pictures. This task simultaneously presents a novel and a familiar image to a monkey and then monitors their visual scan paths. Because the age-associated decline in preferential viewing of novel images was correlated with altered saccade dynamics that are known to be related to dopamine dysfunction, it was suggested that the decreased novelty preference observed in old monkeys may be due to decreased dopamine levels (Insel et al., 2008). Taken together, these data suggest that age-associated alterations in dopamine transmission could also contribute to the results observed in the current study.

6.4.4 Conclusions

Age-associated impairments in object recognition do not appear to result from ‘object forgetting’ in aged rats. Rather, the current data are consistent with a view that functional alterations in the perirhinal cortex, which might occur during advanced age, lead to an increased vulnerability in old animals to the interfering effects of stimuli encountered during extended delay periods. This interference by extraneous stimuli results in old rats identifying novel objects as familiar. One explanation for this increased susceptibility to interference could be a diminished ability in advanced age to pattern separate between complex stimuli that share common features; an impairment that is also observed in rats with perirhinal cortex lesions (McTighe et al., 2008). Additionally, it is possible that age-related reductions in mesolimbic dopamine projections to the perirhinal cortex contribute to decreased sensitivity for detection of novelty in aged animals.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the McKnight Brain Research Foundation, and NIH grants AG003376, NS054465, and HHMI5205889. We would also like express our gratitude to Tim Bussey, Lisa Saksida and Stephanie McTighe for sharing their idea for the novel/repeat spontaneous object recognition task used in Experiment 2, and for their insights regarding the potential role of interfering stimuli encountered during delays on task performance. Additionally, we would also like to thank Andrew Maurer, Michael Montgomery, Michelle Carroll and Luann Snyder for help with completing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/bne

References

- Abe H, Ishida Y, Iwasaki T. Perirhinal N-methyl-D-aspartate and muscarinic systems participate in object recognition in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2004;356(3):191–194. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainge JA, Heron-Maxwell C, Theofilas P, Wright P, de Hoz L, Wood ER. The role of the hippocampus in object recognition in rats: examination of the influence of task parameters and lesion size. Behav Brain Res. 2006;167(1):183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barense MD, Bussey TJ, Lee AC, Rogers TT, Davies RR, Saksida LM, Murray EA, Graham KS. Functional specialization in the human medial temporal lobe. J Neurosci. 2005;25(44):10239–10246. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2704-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barense MD, Gaffan D, Graham KS. The human medial temporal lobe processes online representations of complex objects. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45(13):2963–2974. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barense MD, Henson RN, Lee AC, Graham KS. Medial temporal lobe activity during complex discrimination of faces, objects, and scenes: Effects of viewpoint. Hippocampus. 2009 doi: 10.1002/hipo.20641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barili P, De Carolis G, Zaccheo D, Amenta F. Sensitivity to ageing of the limbic dopaminergic system: a review. Mech Ageing Dev. 1998;106(1–2):57–92. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(98)00104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes CA, Rao G, McNaughton BL. Functional integrity of NMDA-dependent LTP induction mechanisms across the lifespan of F-344 rats. Learn Mem. 1996;3(2–3):124–137. doi: 10.1101/lm.3.2-3.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartko SJ, Winters BD, Cowell RA, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ. Perceptual functions of perirhinal cortex in rats: zero-delay object recognition and simultaneous oddity discriminations. J Neurosci. 2007a;27(10):2548–2559. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5171-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartko SJ, Winters BD, Cowell RA, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ. Perirhinal cortex resolves feature ambiguity in configural object recognition and perceptual oddity tasks. Learn Mem. 2007b;14(12):821–832. doi: 10.1101/lm.749207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolini L, Casamenti F, Pepeu G. Aniracetam restores object recognition impaired by age, scopolamine, and nucleus basalis lesions. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996;53(2):277–283. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter MG, Murray EA. Impairments in visual discrimination learning and recognition memory produced by neurotoxic lesions of rhinal cortex in rhesus monkeys. Eur J Neurosci. 2001a;13(6):1228–1238. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter MG, Murray EA. Opposite relationship of hippocampal and rhinal cortex damage to delayed nonmatching-to-sample deficits in monkeys. Hippocampus. 2001b;11(1):61–71. doi: 10.1002/1098-1063(2001)11:1<61::AID-HIPO1021>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent NJ, Squire LR, Clark RE. Spatial memory, recognition memory, and the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(40):14515–14520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406344101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozinsky CJ, Yonelinas AP, Kroll NE, Ranganath C. Lag-sensitive repetition suppression effects in the anterior parahippocampal gyrus. Hippocampus. 2005;15(5):557–561. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley MJ, Gaffan D. Perirhinal cortical contributions to object perception. Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;10(3):100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffalo EA, Ramus SJ, Clark RE, Teng E, Squire LR, Zola SM. Dissociation between the effects of damage to perirhinal cortex and area TE. Learn Mem. 1999;6(6):572–599. doi: 10.1101/lm.6.6.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffalo EA, Ramus SJ, Squire LR, Zola SM. Perception and recognition memory in monkeys following lesions of area TE and perirhinal cortex. Learn Mem. 2000;7(6):375–382. doi: 10.1101/lm.32100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunzeck N, Duzel E. Absolute coding of stimulus novelty in the human substantia nigra/VTA. Neuron. 2006;51(3):369–379. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunzeck N, Schutze H, Stallforth S, Kaufmann J, Duzel S, Heinze HJ, Duzel E. Mesolimbic novelty processing in older adults. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17(12):2940–2948. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]