Abstract

Background. The pathogenetic mechanisms of fetal growth restriction associated with placental malaria are largely unknown. We sought to determine whether placental malaria and related inflammation were associated with disturbances in the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) axis, a major regulator of fetal growth.

Method. We measured IGF-1 and IGF-2 concentrations in plasma from 88 mother-neonate pairs at delivery and IGF binding proteins 1 and 3 (IGFBP-1 and IGFBP-3, respectively) in cord plasma from a cohort of Papua New Guinean women with and without placental malaria. Messenger RNA levels of IGF-1, IGF-2, and the IGF receptors were measured in matched placental biopsy specimens.

Results. Compared with those for uninfected pregnancies, IGF-1 levels were reduced by 28% in plasma samples from women with placental Plasmodium falciparum infection and associated inflammation (P = .007) and by 25% in their neonates (P = .002). Levels of fetal IGFBP-1 were elevated in placental malaria with and without inflammation (P = .08 and P = .006, respectively) compared with uninfected controls. IGF-2 and IGFBP-3 plasma concentrations and placental IGF ligand and receptor messenger RNA transcript levels were similar across groups.

Conclusion. Placental malaria-associated inflammation disturbs maternal and fetal levels of IGFs, which regulate fetal growth. This may be one mechanism by which placental malaria leads to fetal growth restriction.

Placental malaria is a leading cause of low birth weight (LBW) in Africa, resulting in 75,000–200,000 infant deaths each year. In these settings, LBW is more commonly due to fetal growth restriction (FGR) rather than preterm delivery [1, 2]. The sequestration of Plasmodium falciparum–infected erythrocytes (IEs) in the placental intervillous spaces, termed placental malaria, can trigger the recruitment of inflammatory cells and production of cytokines, which are strongly associated with LBW [3–5]. The biological mechanisms leading to LBW are not known, but placental insufficiency and endocrine disturbances may underlie the pathogenesis.

The placenta functions as an endocrine organ and transmits hormonal signals between the mother and the developing fetus to ensure adequate support for sustained fetal growth. Few studies have examined maternal endocrine profiles in the context of malaria in pregnancy [6–8], and no study has investigated the relationship between growth-regulating hormones and LBW in placental malaria.

The insulin-like growth factor (IGF) system is the most influential growth-promoting factor in fetal life [9], with roles in regulating placental development and function, transplacental exchange of nutrients, and fetal growth. In mice, genetic ablation of insulin-like growth factor 1 gene (Igf1) or insulin-like growth factor 2 gene (Igf2) decreases birth weight by 40% [10], and double knock-out of Igf1 and Igf2, or of the IGF-1 receptor gene (Igf1r), further restricts fetal growth [10]. The liver is the main source of circulating IGF-1 in postnatal life [11], but during pregnancy the placenta and the fetus secrete IGFs and regulatory proteins. Fetal IGF-1 and IGF-2 promote fetal growth but have differential actions, which have been attributed to distinct interactions with receptors.

The IGF receptors (IGF-1R and IGF-2R) mediate IGF activity and are abundant in all placental cell types [12] and in the microvillous plasma membrane of the syncytiotrophoblast [13]. Activation of IGF-1R stimulates cell signaling cascades [14] that lead to proliferation, survival, and fetal growth promotion [9], whereas IGF-2R lacks the cell signaling domain [11], acting as a sink to sequester free IGF-2, and is considered antimitogenic.

Bioactivity of the IGFs is modulated by the IGF binding proteins (IGFBPs), which transport circulating IGFs. IGFBPs have greater ligand affinity than IGF receptors [15] and thus sequester circulating IGFs to restrict their interactions with the receptors. IGFBP-1 and IGFBP -3 are expressed in abundance at the maternal-fetal interface [15]. IGFBP-1 is an important negative short-term regulator of IGF bioactivity, and levels fluctuate in response to maternal stress and nutritional intake [16–18].

Alterations in the absolute level and bioavailability of the IGFs in maternal, fetal, and placental compartments are implicated in other causes of FGR [9, 11, 19, 20]. However, the relationship between placental malaria, the IGF axis, and birth weight has not been explored.

We investigated whether placental malaria and the associated inflammation impacted on the IGF system at delivery and whether changes in the IGF axis were consistent with the IGF profile observed in FGR of other etiologies.

METHODS

Study Design

Pregnant women attending antenatal care at Alexishafen Health Centre, Madang, Papua New Guinea, between September 2005 and October 2007 were recruited to a longitudinal study of malaria in pregnancy, following written informed consent. At delivery, babies were weighed, Ballard scores were used to estimate gestational age, and maternal hemoglobin levels were measured. Maternal and cord blood was collected in K2-ethylenediaminetetreacetic acid vials (BD), and separated plasma was frozen at −80°C. A random sampling of placental biopsy specimens were either collected into 10% neutral buffered formalin for histological examination for placental malaria infection or frozen at −80°C in RNAlater (Ambion) for RNA analysis. The Medical Research Advisory Council of Papua New Guinea and the Human Research Ethics Committee of Melbourne Health, Australia, approved the study. Samples used in the present study are from a subset of participants recruited.

Placental Histology and Inclusion Criteria

Placental histology was examined as described by Rogerson et al [3]. Full-thickness Giemsa-stained biopsy specimens were examined, and IEs, monocytes containing malaria pigment, and malaria pigment in fibrin were noted. Where IEs were detected, 500 intervillous cells (IEs, erythrocytes, or otherwise) were counted, and placentas were classified as either placental malaria without inflammation (≥1% IEs and <1% pigmented monocytes), denoted as placental malaria (PM), or placental malaria with monocyte infiltrate (PMM) (≥1% IEs and ≥1% pigmented monocytes). Plasma samples from a subset of ∼30 women from each group, including uninfected controls (no evidence of either IEs or pigmented monocytes) with live singleton deliveries were randomly selected for IGF assays.

Placental RNA Extraction and Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reacion (qPCR)

RNA extraction from placental tissue biopsy specimens was performed using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), according to the supplier's instructions. Contaminating DNA was removed by DNAse treatment (Ambion) and confirmed by a lack of amplification signal following real-time qPCR. Two micrograms of RNA were reverse transcribed according to supplier's recommendations (Superscript III; Invitrogen), and complementary DNA was diluted 2-fold in DNAse-free water and stored at −20°C until use. Real-time qPCR was performed in duplicate using a SYBR Green master mix (Applied Biosystems) dispensed by liquid handling robot (Eppendorf) on an ABI 7900HT real-time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems). Primer sequences were derived from those in previous studies or designed using Primer Express (Supplementary Table 1). Transcript levels of target genes (IGF1, IGF2, IGF1R, and IGF2R) were quantified in 88 placental biopsy specimens by real-time qPCR using a ratio of transcription (R) determined by the equation R = [E(target)ΔCt]/[E(housekeeper)ΔCt], which corrects for any potential differences in PCR efficiency (E) between primer pairs, where the difference in cycle threshold (ΔCt) between control and sample, and where E = 10−1/slope. Slope is calculated from the fluorescence generated by a 7- point standard curve of pooled complementary DNA for each primer pair. The relative amplification efficiency of each target gene was >93% of the housekeeping gene tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein, zeta polypeptide (YWHAZ).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Total IGF-1 and IGF-2 concentrations in cord and maternal plasma were determined by ELISA in 88 mother-infant pairs. Four additional maternal samples that met selection criteria but lacked the corresponding cord sample were included. Cord IGFBP-1 and IGFBP-3 levels were measured by ELISA in 87 (due to volume limitation) and 88 samples, respectively; IGFBP-1 concentrations in cord plasma were log-transformed to normalize the data before analysis. Intra- and inter-assay variability did not exceed 6%, except for IGF-2 and IGFBP-3 ELISAs, which varied between assays by 8.5% and 6.5%, respectively. ELISA kits were purchased from Diagnostic Systems Laboratory.

Statistical Analysis

Univariate analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software version 4.03 (Graphware). Parametric data, represented as mean and standard deviation (SD), were compared using the Student t test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) for ≥3 groups. Nonparametric data, shown as median and interquartile range (IQR), were compared using the Kruskall-Wallis test. Correlation analyses used the Pearson correlation r for parametric analysis or the Spearman ρ for nonparametric correlation. Linear regression was used to determine the slope of the correlation and is expressed as the correlation coefficient ß (± standard error). Multivariate analysis and odds ratio (OR) calculations were performed using Stata software (version 10; Stata). Results for which P ≤ .05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics at Delivery

Table 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics and placental histology of the 92 participating women. Three-quarters of all PMM cases had IEs of ≥1% and ≥1% pigmented monocytes, whereas 60% of PM cases had <1% of IEs. In total, 58 women had placental malaria; 27 were positive for both placental malaria and monocyte infiltrate (PMM), and 31 had placenta malaria infection only (PM). Thirty-four women were uninfected. Maternal age (P = .03), gravidity (P = .02), and gestational age at delivery (P = .05) of the women with PMM were significantly lower than those of the uninfected controls, whereas hemoglobin levels were unchanged between groups.

Table 1.

Univariate Analysis of Maternal Characteristics According to Placental Malaria Histopathology

| Malaria histopathology | Uninfected (n = 34) | PM (n = 31) | PMM (n = 27) | P (ANOVA) |

| Maternal age at enrollment, years | 24.7 (5.2) | 24.7 (4.2) | 21.9 (4.0)a | .03 |

| Maternal weight, kg | 55.0 (5.2) | 55.0 (7.1) | 55.6 (5.7) | .9 |

| Gravidity, number of pregnancies | 2.3 (1.4) | 2.4 (1.3) | 1.6 (1.0)b | .02 |

| Delivery gestational age, weeks | 38.4 (2.3) | 37.6 (2.5) | 36.8 (2.6)a | .05 |

| Maternal hemoglobin level, g/dL | 9.2 (2.3) | 9.5 (1.7) | 9.1 (1.8) | .6 |

| Birth weight, g | 2970 (510) | 2870 (460) | 2600 (420)b | .02 |

| IEs on placental histology, % | 0 (0) | 2.4 (2) | 20 (18) | … |

| Monocytes on placental histology, % | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10.0 (9.8) | … |

NOTE. Data are mean (SD). Women with placental malaria (PM) infection and monocyte infiltrate (PMM) were on average younger and primigravidae and delivered younger and lighter neonates than uninfected women. The percentage of infected erythrocytes (IEs) and monocytes were determined from 500 cells counted from the intervillous spaces in infected placentae only. ANOVA, analysis of variance.

P ≤ .05 for PMM versus uninfected controls (t test).

P ≤ .01 for PMM versus uninfected controls (t test).

Placental Malaria With Inflammation Is Associated With Decreased Birth Weight

The mean birth weight of infants from pregnancies with PMM was 370 g less than that for infants delivered in the absence of infection (P = .01) (Table 2). Infants delivered from pregnancies with PM were 100 g lighter than infants born from uninfected women. Women with PMM had 3 times the risk of delivering a LBW infant (weight, <2500 g; OR, 3.0; 95% confidence interval [CI], .9–10.4; P = .08) compared with uninfected women, whereas there was no increased risk in women with PM alone (OR, .8; 95% CI, .2–3.4; P =.8). Because women with PMM and uninfected women had significantly different maternal age, gravidity, and gestational age at delivery, multivariate analysis was performed to determine the relative impact of placental malaria with or without monocyte infiltrate on birth weight (Table 2). After adjusting for gestational age, PMM reduced mean birth weight by 200 g compared with babies of uninfected women (P = .04). Furthermore, when we stratified women by gravidity and controlled for the influence of gestational age and maternal age, the reduction in birth weight with PMM was limited to primigravidae, who delivered infants nearly 300 g lighter than those of matched uninfected women (P = .02) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate Analysis of the Impact of Placental Malaria With and Without Monocyte Infiltrate on Reduction in Birth Weight

| All gravidities | Primigravidae | Multigravidae | ||

| Placental histology | Mean difference in birth weight compared to uninfected controls,a g [95% CI] (P) | Adjusted weight difference,b g [95% CI] (P) | Adjusted weight difference,c g [95% CI] (P) | Adjusted weight difference,c g [95% CI] (P) |

| PM (n = 31; PG, 9; MG, 22) | −100[285 to 156](NS) | 5[170 to 179](NS) | −13[−275 to 249](NS) | 1[−240 to 242](NS) |

| PMM (n = 27; PG, 19; MG, 8) | −370d[−565 to −99](.01) | −200e[394 to −6](.04) | −291e[−532 to −51](.02) | 45[301 to 392](NS) |

NOTE. Change in mean birth weight in neonates delivered to women with placental malaria (PM) or PM with monocyte infiltrate (PMM) compared with uninfected controls. CI, confidence interval; MG, multigravidae; NS, nonsignificant (P > .05); PG, primigravidae.

On average (unadjusted), both PM, and to a greater extent PMM, had decreased birth weight compared with women without infection.

Adjusting for the effect of gestational age at delivery on birth weight, this decrease remained significant in the PMM group only.

Stratifying for gravidity, and adjusting for maternal and gestational age, a significant reduction in birth weight was observed in primigravid women only.

P ≤ .01 for PMM group vs uninfected controls (t test).

P ≤ .05 for PMM group vs uninfected controls (t test).

Placental Malaria and Inflammation Reduce Maternal IGF-1 Concentrations

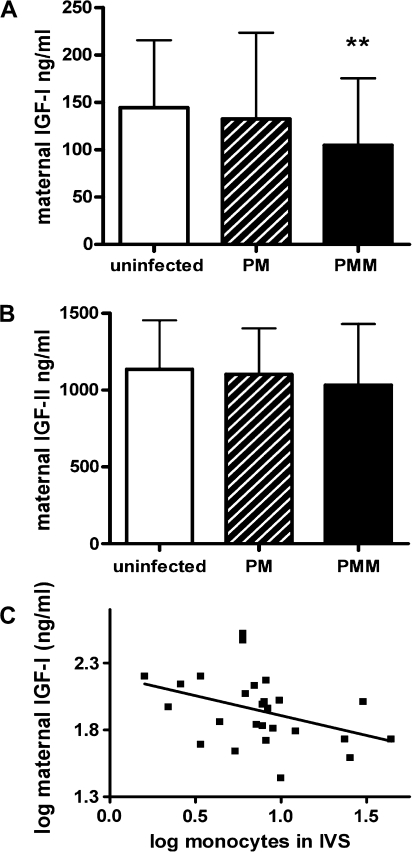

We measured levels of IGF-1 and IGF-2 protein by ELISA in maternal plasma samples collected at delivery. The mean total IGF-1 concentration in women with PMM was 28% lower than in uninfected women (P = .007) (Figure 1A), whereas IGF-2 levels were similar across all cohorts (Figure 1B). In the whole cohort, maternal IGF-1 concentration was not correlated with birth weight (P = .4), gestational age (P = .4), or gravidity (P = .2), but among women with PMM there was a significant negative correlation between the extent of monocyte infiltrate and maternal IGF-1 levels (n = 27; r = −.4; P = .05) (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Maternal insulin-like growth factor (IGF) concentrations in women with and without placental malaria. Maternal IGF-1 and IGF-2 levels (mean ± SD) were measured in plasma samples of uninfected women (n = 34), women with placental malaria (PM; n = 31), and women with placental malaria with monocyte infiltrate (PMM; n = 27). Maternal IGF-1 concentrations differed significantly between groups (P = .03; analysis of variance [ANOVA]), with levels in the PMM group being significantly less than those in the uninfected control group (**P = .007 vs uninfected; t test) (A). Maternal IGF-2 concentrations did not differ between groups (P = .5; ANOVA) (B). Log maternal IGF-1 concentrations from mothers with PMM (n = 27) demonstrate a negative correlation with the degree of monocyte infiltration (log number of monocytes per 500 cells in the intervillous spaces) measured by placental histology (r = −.4; P = .05) (C).

Placental Malaria Does Not Alter Placental IGF Transcript Levels

We measured expression of messenger RNA (mRNA) transcripts for IGF1, IGF2, IGF1R, and IGF2R in 88 placental biopsy specimens by real-time qPCR (Table 3). Ct values for YWHAZ were not different between groups (Kruskall-Wallis test; P = .7). Transcript levels of all 4 genes did not differ significantly between placentas with and without malaria infection and/or monocyte infiltrate.

Table 3.

Insulin-like Growth Factor Ligand and Receptor Gene Messenger RNA Transcript Levels in Placental Biopsy Specimens

| Gene | Uninfected (n = 31) | PM (n = 31) | PMM (n = 26) | P |

| IGF1 | .43 (.32–.65) | .42 (.26–.63) | .36 (.29–.50) | .5 |

| IGF2 | .85 (.41–1.87) | 1.23 (.45–2.14) | 1.40 (.53–3.0) | .4 |

| IGF1R | 1.30 (1.01–1.71) | 1.44 (1.12–2.00) | 1.32 (1.17–2.05) | .7 |

| IGF2R | .61 (.47–.80) | .57 (.42–.80) | .70 (.58–1.00) | .2 |

NOTE. Data are median (interquartile range) transcript levels. In each placental sample, transcript levels for target and housekeeper genes were normalized to a reference sample of pooled complementary DNA. IGF1, insulin-like growth factor 1; IGF1R, insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor; IGF2, insulin-like growth factor 2; IGF2R, insulin-like growth factor 2 receptor; PM, placental malaria; PMM, placental malaria with monocytes.

Total Levels and Bioavailability of Fetal IGF-1 Are Reduced in Placental Malaria and Monocyte Infiltrates

To evaluate the effect of placental malaria and the associated inflammation on the fetal compartment of the IGF axis, we measured concentrations of total IGF-1, IGF-2, IGFBP-1, and IGFBP-3 in cord plasma samples.

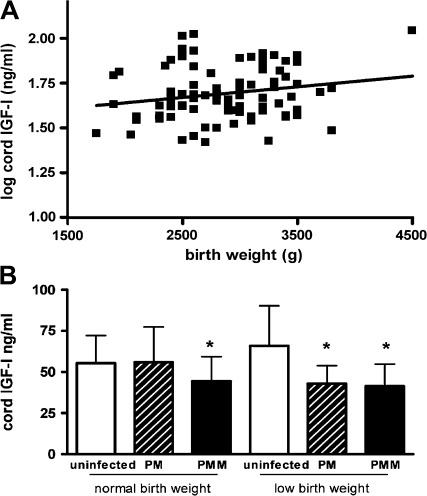

IGF-1 concentration was reduced by 25% in the PMM group compared with infants from uninfected placentas (P = .002) (Figure 2B), whereas IGF-2 concentrations in cord plasma were similar across the 3 groups (ANOVA value, .9) (Figure 2A). Infants delivered from pregnancies with PM alone had IGF-1 concentrations that were intermediate between those of the uninfected and PMM groups. Cord IGF-1 concentration did not vary with gravidity (n = 88), nor did it vary with placental parasitemia in babies of infected women (n = 57) nor with monocyte infiltrate in babies with PMM (n = 26). Cord IGF-1 concentration was weakly correlated with birth weight (n = 83; r = .2; P = .06) (Figure 3A) and to a lesser extent gestational age (n = 80; r = .2; P = .07). After adjusting for gestational age, the relationship between cord IGF-1 concentrations and birth weight was substantially strengthened (R2 = .5; P = .001).

Figure 2.

Fetal insulin-like growth factor (IGF) and IGF binding protein (IGFBP) levels. Concentrations of IGF-1, IGF-2, IGFBP-1, and IGFBP-3 were measured in cord plasma in uninfected (n = 31) placental malaria (PM; n = 30 for IGFBP-1; n = 31 for other analytes) and placental malaria with monocyte infiltrate (PMM; n = 26) Concentrations of IGF-2 (mean ± SD) did not differ significantly (P = .9; analysis of variance [ANOVA]) (A), whereas cord IGF-1 concentrations were significantly different between groups (P = .007; ANOVA) (B). **P = .002 for PMM group vs uninfected control group (t test). IGFBP-1 concentrations (median ± IQR) were normalized by log transformation. Log IGFBP-1 values differed significantly between groups (P = .005; ANOVA) (C). *P = .08 for PMM group vs uninfected control group (t test on log values); **P = .006 for PM group vs uninfected control group (t test on log values). IGFBP-3 concentrations (mean ± SD) were not statistically different between groups (P = .9; ANOVA) (D). The estimated level of free IGF-1 in cord blood (log ratio of IGF-1 to IGFBP-3) differed significantly between groups (P = .004; ANOVA) (E). *P ≤ .02 for PM group vs uninfected control group (t test); ***P < .001 for PMM group vs uninfected control group (t test).

Figure 3.

Relationship between fetal insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) and birth weight. Among all deliveries in the groups (n = 88), log cord IGF-1 level and birth weight were positively correlated (r = .2; P = .06) (A). IGF-1 concentration (mean ± SD) differed significantly (analysis of variance F[5, 77], 2.9; P = .02) in cord blood from the uninfected control, placental malaria (PM), and placental malaria with monocyte infiltrate (PMM) pregnancies according to birth weight category (normal birth weight [NBW], ≥2.5 kg; low birth weight [LBW], <2.5 kg). *P = .02 for PMM group vs uninfected control group among NBW infants (t test); *P = .02 for PM group vs uninfected control group among LBW infants (t test); *P = .04 for PMM group vs uninfected control group for LBW infants (t test).

Compared with infants born from uninfected pregnancies, the median IGFBP-1 concentration was 80% higher in infants born in the presence of PM (P =.006) and 40% higher in infants delivered to the PMM group (P = .08) (Figure 2C). No significant differences were observed in cord plasma IGFBP-3 concentration between uninfected and PM categories (ANOVA F[2, 81], .2; P = .9) (Figure 2D). However, because of the biological relationship between ligand and binding protein, the ratio of log IGF-1 concentration to log IGFBP-3 concentration (as proxy for free IGF-1 [21]) was examined in relation to placental infection (Figure 2E). Compared with uninfected pregnancies, the mean estimated free fetal IGF-1 level was reduced by 5% in PM cases (P =.02) and by 10% in the presence PMM (P <.001).

To further examine the possibility that diminished fetal IGF-1 is a key pathogenic mechanism leading to LBW in placental malaria with inflammation, cord IGF-1 levels were compared between normal-birth-weight (≥2.5 kg) and LBW (<2.5 kg) infants delivered from uninfected pregnancies and those with PM and PMM (Figure 3B). Both normal-birth-weight and LBW infants from the PMM group had lower IGF-1 concentrations (P = .02 and P = .04, respectively) than the respective birth weight group from uninfected pregnancies (Figure 3B), and LBW infants from the PMM group displayed the most severe reduction in IGF-1 concentration.

DISCUSSION

Although the causal relationship between placental malaria and LBW is well recognized, little is known about the pathogenetic mechanisms leading to FGR in malaria. We investigated whether placental malaria and the associated inflammation caused disturbances in the IGF axis in the mother, placenta, or fetus. In agreement with previous studies in areas where malaria is endemic [3, 4], the greatest impact of placental malaria on birth weight was observed in infants born with placental malaria and monocyte infiltrate, which was most common in primigravidae.

We have identified changes in the IGF axis in mothers and infants with placental malaria and inflammation consistent with the endocrine profile of growth-restricted infants [19, 22]. The most severe attenuation of growth-promoting IGF-1 occurred in LBW infants delivered from placentas with malaria and inflammation, which suggests a pathogenetic link between inflammation and decreased IGF-1 levels, leading to LBW. We observed a strong negative association between maternal IGF-1 level and the extent of placental monocyte infiltrates. Although we did not find evidence of a statistical association between maternal IGF-1 levels and birth weight, very few studies have demonstrated a direct relationship between circulating maternal IGF-1 level and birth weight [22, 23], and it is unlikely that maternal IGF-1 levels during pregnancy could be used to predict pregnancies at risk of LBW.

Although maternal IGFs are not transferred across the placenta, they promote fetal growth indirectly through modulation of placental nutrient partitioning. Nutrient transporters are important downstream targets of the IGF system, and physiological levels of IGF-1 stimulate in vitro glucose and amino acid transporter expression and activity in trophoblast cell cultures [24, 25]. The malaria-associated inflammatory events reducing maternal IGF-1 may lead to impaired nutrient delivery to the fetus.

Several physiological explanations could account for the diminished maternal IGF-1 concentrations we have observed in placental malaria with inflammation. Previous studies have shown the IGF axis is influenced by hypoxia, nutrition, cortisol [26], and inflammatory cytokines [27–29]. Although there is no evidence that placental malaria causes hypoxia, [30], elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines [5, 31–33] and glucocorticoids [6, 8] observed during malaria in pregnancy could influence the IGF axis. Whether these processes are responsible for the decreased IGF-1 levels (and therefore fetal growth) that we have observed in placental malaria with inflammation deserves further investigation. Whatever the intermediate signal, the lack of a pronounced effect of parasite sequestration alone on circulating IGF-1, coupled with the strong negative association between inflammatory load and maternal IGF-1 levels, suggests that the chronic nature of PMM infections coupled with the inflammatory processes are the driving force reducing IGF-1 in the maternal compartment at delivery.

Throughout pregnancy, the fetal liver synthesizes IGFs [15], which act in part to regulate materno-fetal glucose transfer according to fetal demand. IGFs also have a direct trophic effect in fetal target tissues, via activation of the IGF-1R expressed in fetal organs. Decreased levels of fetal IGF-1, such as we have described in placental malaria and inflammation, are likely to negatively affect fetal growth through decreased cellular proliferation and indirectly by limiting transplacental passage of nutrients. Indeed, evidence from our study supports a pathogenetic link between attenuated IGF-1 level and birth weight, as cord IGF-1 level was positively associated with birth weight, and LBW infants from PMM displayed the most severe reduction in IGF-1 levels. These observations are consistent with other studies, in which cord blood IGF-1 concentration at term is positively correlated with fetal growth [34–36] and is diminished in human FGR [9, 11, 20, 37]. Furthermore, the reduction in cord IGF-1 concentration and concomitant reduction in birth weight in this study are consistent with the 200–500 g decrease in birth weight reported in other studies with similar perturbations in IGF levels [34, 38]. The mechanisms by which fetal IGF-1 levels are decreased in human studies remain unclear (although it may be inversely related to cortisol levels [37]), and in animal models, restriction of maternal nutrition [39], placental blood flow [40], and oxygen [41] all decrease fetal IGF-1 concentrations.

IGF-2 is more abundant in fetal circulation than IGF-1 [34], but the relationship between cord IGF-2 levels and birth weight is inconsistent [20, 34–36, 42, 43]; cord IGF-2 level may be correlated with ponderal index and placental weight [36], but neither measure was available for the present cohorts. Our data are consistent with published studies in associating placental disease at delivery with decreased IGF-1, rather than IGF-2 [20, 35, 36]. Nevertheless, IGF-2 is an important regulator of placental development and fetal growth during early pregnancy. Further studies should examine whether perturbed levels of growth-regulating hormones such as IGF-2 in early pregnancy are involved in development of FGR.

Elevated levels of cord IGFBP-1 that we observed in placental malaria may act to diminish the bioavailability of IGF-1. Similar IGFBP-1 profiles have been observed in cord blood of fetuses experiencing maternal stress [44]. We found no evidence of a relationship between IGFBP-1 concentration and birth weight, and it may exert its influence instead through its effect on IGF-1 availability in babies whose IGF-1 levels are already compromised by placental malaria. The mechanisms causing elevated concentrations of IGFBP-1 in growth-restricted human infants are not currently known.

Placental malaria did not affect total IGFBP-3 concentrations; indeed, IGFBP-1 concentrations are more sensitive to hypoxia [41] and endocrine [44] regulation than IGFBP-3 concentrations. The decreased ratio of IGF-1 to IGFBP-3 we report in placental malaria is a surrogate measure of free IGF-1 [21] and supports the notion that free, as well as total, IGF-1 at delivery is reduced in infants born to mothers with PM, and to a greater extent, in placental malaria with monocyte infiltrate.

By mRNA analysis of placental tissue, we did not find any significant changes in IGF-related gene transcription. In contrast, significantly increased placental IGF1 and/or IGF2 mRNA levels have been reported in several but not all human studies of FGR [45–49]. Some of these studies have examined placental mRNA transcript levels in smaller sized studies than ours [46, 48], which suggests that our study size was adequately powered. The observation that placental transcripts for components of the local IGF system remained unchanged with malaria infection and associated inflammation implies that autocrine effects of IGFs are perhaps not the locus for modulation of fetal growth in malaria-affected pregnancies. Alternatively, closer examination of IGF levels in the syncytiotrophoblast layer by laser capture microdissection might reveal differences that are not apparent in biopsied placental tissue [30].

A potential limitation to this study is that the detection method used for IGF-1 and IGF-2 measured total (bound and unbound fractions) rather than bioactive (free) ligand, which constitutes ∼1% of total IGF [20]. However, concentrations of total IGF correlate with those of free IGF [20, 34] and frequently associate with clinical indices of fetal growth [20, 35, 36, 38, 46]. We determined the ratio of IGF-1 to IGFBP-3 in cord samples as a proxy measure of free IGF-1 [21]. A further consideration is that the phosphorylation state of IGFBP-1 during gestation affects the ligand binding activity [11]. Because measurement of phosphovariants is both time- and cost-intensive, we quantified total IGFBP-1 by ELISA, which does not discriminate between phospho-isoforms but has been validated in other studies [20, 36, 38]. To minimize possible proteolytic degradation of IGFBP-3, which may overestimate IGFBP-3 levels, we restricted samples to a single cycle of freezing and thawing, Future studies that employ more sophisticated detection of IGFBP-1 phospho-isoforms and that take into account free and total fractions of IGF-1 and IGF-2 may reveal additional functional subtleties.

Current theories on the pathogenesis of LBW associated with placental malaria-induced inflammation center on the conflicting immune environment between resolution of infection and the requirement for continued fetal growth. The release of pro-inflammatory cytokines [5, 31, 32] and monocyte infiltrates in the placental intervillous spaces [4] are associated with LBW, but the physiological impact of the inflammatory environment on placental function and fetal growth has not been studied extensively. To date, disturbances in the IGF system relating to fetal growth have been described in preeclampsia, asthma, nutritional deprivation, and maternal stress and in diabetic pregnancies [38, 45], and our study adds malaria to this list. Interventions that specifically target growth restriction through IGF therapy have been shown to prevent FGR in sheep [50] but have yet to be applied to disease in humans. Whether perturbations of the IGF system in humans are an underlying cause of or response to growth restriction remains to be fully elucidated.

This study provides strong evidence of concordant disturbances in the maternal and fetal compartments of the IGF axis with placental malaria and associated inflammation, which have the potential to compromise nutrient partitioning to the fetus and may play a central role in the development of LBW due to FGR in malaria-infected pregnancies.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (project grant number 509185 to S.J.R. and J.G. and project grant number 575534 to J.B. and S.R.); and the Australian Research Council (Future Fellowship to J.B.).

Acknowledgments

We thank the mothers and their families for participation in this study and Sr Valsi and the staff of Alexishafen Health Centre for their enthusiastic cooperation.

References

- 1.Desai M, ter Kuile FO, Nosten F, et al. Epidemiology and burden of malaria in pregnancy. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:93–104. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70021-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guyatt HL, Snow RW. Impact of malaria during pregnancy on low birth weight in sub-Saharan Africa. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:760–9. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.4.760-769.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogerson SJ, Pollina E, Getachew A, Tadesse E, Lema VM, Molyneux ME. Placental monocyte infiltrates in response to Plasmodium falciparum malaria infection and their association with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68:115–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ordi J, Ismail MR, Ventura PJ, et al. Massive chronic intervillositis of the placenta associated with malaria infection. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:1006–11. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199808000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fried M, Muga RO, Misore AO, Duffy PE. Malaria elicits type-1 cytokines in the human placenta: IFN gamma and TNF alpha associated with pregnancy outcomes. J Immunol. 1998;160:2523–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vleugels MP, Brabin B, Eling WM, de Graaf R. Cortisol and Plasmodium falciparum infection in pregnant women in Kenya. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1989;83:173–7. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(89)90632-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vleugels MP, Eling WM, Rolland R, de Graaf R. Cortisol and loss of malaria immunity in human pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1987;94:758–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1987.tb03722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bayoumi NK, Elhassan EM, Elbashir MI, Adam I. Cortisol, prolactin, cytokines and the susceptibility of pregnant Sudanese women to Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2009;103:111–7. doi: 10.1179/136485909X385045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Randhawa R, Cohen P. The role of the insulin-like growth factor system in prenatal growth. Mol GenetMetab. 2005;86:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Efstratiadis A. Genetics of mouse growth. Int J Dev Biol. 1998;42:955–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forbes K, Westwood M. The IGF axis and placental function: a mini review. Horm Res. 2008;69:129–37. doi: 10.1159/000112585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmes R, Porter H, Newcomb P, Holly JM, Soothill P. An immunohistochemical study of type I insulin-like growth factor receptors in the placentae of pregnancies with appropriately grown or growth restricted fetuses. Placenta. 1999;20:325–30. doi: 10.1053/plac.1998.0387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang J, Furesz TC, Lurent RS, Smith CH, Fant ME. Spatial polarization of insulin-like growth factor receptors on the human syncytiotrophoblast. Pediatr Res. 1997;41:258–65. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199702000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forbes K, Westwood M, Baker PN, Aplin JD. Insulin-like growth factor I and II regulate the life cycle of trophoblast in the developing human placenta. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C1313–22. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00035.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han VK, Carter AM. Spatial temporal patterns of expression of messenger RNA for insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins in the placenta of man and laboratory animals. Placenta. 2000;21:289–305. doi: 10.1053/plac.1999.0498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baxter RC. Insulin-like growth factor binding proteins as glucoregulators. Metabolism. 1995;44:12–7. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(95)90215-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallaher BW, Breier BH, Oliver MH, Harding JE, Gluckman PD. Ontogenic differences in the nutritional regulation of circulating IGF binding proteins in sheep plasma. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1992;126:49–54. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1260049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li C, Schlabritz-Loutsevitch NE, Hubbard GB, et al. Effects of maternal global nutrient restriction on fetal baboon hepatic insulin-like growth factor system genes gene products. Endocrinology. 2009;150:4634–42. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kajantie E. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I, and IGF binding protein (IGFBP)-3, phosphoisoforms of IGFBP-1 and postnatal growth in very-low-birth-weight infants. Horm Res. 2003;60(suppl 3):124–30. doi: 10.1159/000074513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lo HC, Tsao LY, Hsu WY, Chen HN, Yu WK, Chi CY. Relation of cord serum levels of growth hormone, insulin-like growth factors, insulin-like growth factor binding proteins, leptin, and interleukin-6 with birth weight, birth length, and head circumference in term and preterm neonates. Nutrition. 2002;18:604–8. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(01)00811-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris TG, Strickler HD, Yu H, et al. Specimen processing time and measurement of total insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I), free IGF-I, and IGF binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) Growth Horm IGF Res. 2006;16:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holmes R, Montemagno R, Jones J, Preece M, Rodeck C, Soothill P. Fetal and maternal plasma insulin-like growth factors and binding proteins in pregnancies with appropriate or retarded fetal growth. Early Hum Dev. 1997;49:7–17. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(97)01867-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McIntyre HD, Serek R, Crane DI, et al. Placental growth hormone (GH), GH-binding protein, and insulin-like growth factor axis in normal, growth-retarded, and diabetic pregnancies: correlations with fetal growth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:1143–50. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.3.6480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kniss DA, Shubert PJ, Zimmerman PD, Landon MB, Gabbe SG. Insulinlike growth factors: their regulation of glucose and amino acid transport in placental trophoblasts isolated from first-trimester chorionic villi. J Reprod Med. 1994;39:249–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fang J, Mao D, Smith CH, Fant ME. IGF regulation of neutral amino acid transport in the BeWo choriocarcinoma cell line (b30 clone): evidence for MAP kinase-dependent and MAP kinase-independent mechanisms. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2006;16:318–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miell JP, Taylor AM, Jones J, et al. The effects of dexamethasone treatment on immunoreactive and bioactive insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) and IGF-binding proteins in normal male volunteers. J Endocrinol. 1993;136:525–33. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1360525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hashimoto R, Sakai K, Matsumoto H, Iwashita M. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) inhibits insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) activities in human trophoblast cell cultures through IGF-I/insulin hybrid receptors. Endocr J. 2010;57:193–200. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k09e-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arkins SRN, Brunke-Reese DL, Biragyn A, Kelley KW. Interferon-gamma inhibits macrophage insulin-like growth factor-I synthesis at the transcriptional level. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9:350–60. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.3.7776981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Price WA, Moats-Staats BM, Stiles AD. Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines regulate insulin-like growth factor binding protein production by fetal rat lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:283–9. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.3.4601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boeuf P, Tan A, Romagosa C, et al. Placental hypoxia during placental malaria. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:757–65. doi: 10.1086/526521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diouf I, Fievet N, Doucoure S, et al. IL-12 producing monocytes and IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha producing T-lymphocytes are increased in placentas infected by Plasmodium falciparum. J Reprod Immunol. 2007;74:152–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogerson SJ, Brown HC, Pollina E, et al. Placental tumor necrosis factor alpha but not gamma interferon is associated with placental malaria and low birth weight in Malawian women. Infect Immun. 2003;71:267–70. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.1.267-270.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fievet N, Moussa M, Tami G, et al. Plasmodium falciparum induces a Th1/Th2 disequilibrium, favoring the Th1-type pathway, in the human placenta. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1530–4. doi: 10.1086/320201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klauwer D, Blum WF, Hanitsch S, Rascher W, Lee PD, Kiess W. IGF-I, IGF-II, free IGF-I and IGFBP-1, -2 and -3 levels in venous cord blood: relationship to birthweight, length and gestational age in healthy newborns. Acta Paediatr. 1997;86:826–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb08605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geary M, Pringle P, Rodeck CH, Kingdom JC, Hindmarsh PC. Sexual dimorphism in the growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor axis at birth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:3708–14. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-022006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ong K, Kratzsch J, Kiess W, Costello M, Scott C, Dunger D. Size at birth and cord blood levels of insulin, insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I), IGF-II, IGF-binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1), IGFBP-3, and the soluble IGF-II/mannose-6-phosphate receptor in term human infants. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:4266–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.11.6998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kyriakakou M, Malamitsi-Puchner A, Mastorakos G, et al. The role of IGF-1 and ghrelin in the compensation of intrauterine growth restriction. Reprod Sci. 2009;16:1193–200. doi: 10.1177/1933719109344629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clifton VL, Hodyl NA, Murphy VE, Giles WB, Baxter RC, Smith R. Effect of maternal asthma, inhaled glucocorticoids and cigarette use during pregnancy on the newborn insulin-like growth factor axis. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2010;20:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brameld JM, Mostyn A, Dandrea J, et al. Maternal nutrition alters the expression of insulin-like growth factors in fetal sheep liver and skeletal muscle. J Endocrinol. 2000;167:429–37. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1670429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McLellan KC, Hooper SB, Bocking AD, et al. Prolonged hypoxia induced by the reduction of maternal uterine blood flow alters insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1) and IGFBP-2 gene expression in the ovine fetus. Endocrinology. 1992;131:1619–28. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.4.1382958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bennet L, Oliver MH, Gunn AJ, Hennies M, Breier BH. Differential changes in insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins following asphyxia in the preterm fetal sheep. J Physiol. 2001;531:835–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0835h.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Osorio M, Torres J, Moya F, Pezzullo J, Salafia C, Baxter RSJ, Fant M. Insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) and IGF binding proteins-1, -2, and -3 in newborn serum: relationships to fetoplacental growth at term. Early Hum Dev. 1996;46:15–26. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(96)01737-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lassarre C, Hardouin S, Daffos F, Forestier F, Frankenne F, Binoux M. Serum insulin-like growth factors and insulin-like growth factor binding proteins in the human fetus: relationships with growth in normal subjects and in subjects with intrauterine growth retardation. Pediatr Res. 1991;29:219–25. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199103000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kajantie E, Hytinantti T, Koistinen R, et al. Markers of type I and type III collagen turnover, insulin-like growth factors, and their binding proteins in cord plasma of small premature infants: relationships with fetal growth, gestational age, preeclampsia, and antenatal glucocorticoid treatment. Pediatr Res. 2001;49:481–9. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200104000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gratton RJ, Asano H, Han VK. The regional expression of insulin-like growth factor II (IGF-II) and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1) in the placentae of women with pre-eclampsia. Placenta. 2002;23:303–10. doi: 10.1053/plac.2001.0780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Street M, Seghini P, Fieni S, et al. Changes in interleukin-6 and IGF system and their relationships in placenta and cord blood in newborns with fetal growth restriction compared with controls. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;155:567–74. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee M, Jeon Y, Lee S, Park M, Jung S, Kim Y. Placental gene expression is related to glucose metabolism and fetal cord blood levels of insulin and insulin-like growth factors in intrauterine growth restriction. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sheikh S, Satoskar P, Bhartiya D. Expression of insulin-like growth factor-I and placental growth hormone mRNA in placentae: a comparison between normal and intrauterine growth retardation pregnancies. Mol Hum Reprod. 2001;7:287–92. doi: 10.1093/molehr/7.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Street M, Grossi E, Volta C, Faleschini E, Bernasconi S. Placental determinants of fetal growth: identification of key factors in the insulin-like growth factor and cytokine systems using artificial neural networks. BMC Pediatr. 2008;8:24 doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-8-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eremia SC, de Boo HA, Bloomfield FH, Oliver MH, Harding JE. Fetal and amniotic insulin-like growth factor-I supplements improve growth rate in intrauterine growth restriction fetal sheep. Endocrinology. 2007;148:2963–72. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murphy VE. The effect of maternal asthma during pregnancy on placental function and fetal development [doctoral thesis] Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia: School of Medical Practice and Population Health, University of Newcastle; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu Y, Tan R, MacCalman C, et al. IFN-gamma-mediated extravillous trophoblast outgrowth inhibition in first trimester explant culture: a role for insulin-like growth factors. Mol Hum Reprod. 2008;14:281–9. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gan018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, et al. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3:1–11. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]