Abstract

Background:

Prolonged mechanical ventilation (MV) results in a rapid onset of diaphragmatic atrophy that is primarily due to increased proteolysis. Although MV-induced protease activation can involve several factors, it is clear that oxidative stress is a required signal for protease activation in the diaphragm during prolonged MV. However, the oxidant-producing pathways in the diaphragm that contribute to MV-induced oxidative stress remain unknown. We have demonstrated that prolonged MV results in increased diaphragmatic expression of a key stress-sensitive enzyme, heme oxygenase (HO)-1. Paradoxically, HO-1 can function as either a pro-oxidant or an antioxidant, and the role that HO-1 plays in MV-induced diaphragmatic oxidative stress is unknown. We tested the hypothesis that HO-1 acts as a pro-oxidant in the diaphragm during prolonged MV.

Methods:

To determine whether HO-1 functions as a pro-oxidant or an antioxidant in the diaphragm during MV, we assigned rats into three experimental groups: (1) a control group, (2) a group that received 18 h of MV and saline solution, and (3) a group that received 18 h of MV and was treated with a selective HO-1 inhibitor. Indices of oxidative stress, protease activation, and fiber atrophy were measured in the diaphragm.

Results:

Inhibition of HO-1 activity did not prevent or exacerbate MV-induced diaphragmatic oxidative stress (as indicated by biomarkers of oxidative damage). Further, inhibition of HO-1 activity did not influence MV-induced protease activation or myofiber atrophy in the diaphragm.

Conclusions:

Our results indicate that HO-1 is neither a pro-oxidant nor an antioxidant in the diaphragm during MV. Furthermore, our findings reveal that HO-1 does not play an important role in MV-induced protease activation and diaphragmatic atrophy.

Mechanical ventilation (MV) is used clinically to provide adequate alveolar ventilation in patients who cannot do so on their own.1 Common indications for MV include respiratory failure due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, status asthmaticus, and heart failure. Unfortunately, removal from the ventilator (weaning) is frequently difficult.2,3 Specifically, approximately 25% of patients who require MV experience weaning difficulties; this translates to prolonged hospital stays along with increased risk of morbidity and mortality.2,4

Though the cause of weaning failure is complex and can involve several factors, MV-induced diaphragmatic weakness is predicted to be a frequent contributor to weaning failure.5,6 Indeed, prolonged MV promotes a rapid progression of diaphragmatic proteolysis, myofiber atrophy, and contractile dysfunction.7‐12 Although the specific mechanisms responsible for MV-induced diaphragmatic weakness remain unknown, growing amounts of evidence suggest a causal link between the production of reactive oxygen species and MV-induced diaphragmatic atrophy and weakness.7,13‐18 In this regard, MV-induced oxidative stress occurs rapidly within the first 6 h of MV, and diaphragmatic contractile proteins such as actin and myosin are oxidized.13 Additionally, oxidative stress can activate several key proteases (eg, calpain and caspase-3), and activation of these proteases is an important contributor to the MV-induced diaphragmatic atrophy and contractile dysfunction.19‐22

Therefore, understanding the interplay between oxidant production and antioxidant action in the diaphragm during prolonged MV is important. In this context, the current experiment focused on the role of heme oxygenase (HO)-1 as a regulator of redox balance in the diaphragm during MV. HO-1 is an intracellular enzyme localized primarily to the microsomal fraction of the cell.23 This enzyme catalyzes the rate-limiting step in the degradation of heme, resulting in the generation of carbon monoxide, biliverdin, and free iron (Fe2+). After formation, biliverdin is further reduced to bilirubin via biliverdin reductase, and both bilirubin and biliverdin exhibit antioxidant effects. The effect of HO-1-induced iron release is often associated with the induction of iron-sequestering proteins (eg, ferritin) to bind the free iron. Nonetheless, the failure to completely sequester the free iron in the muscle fiber would exert pro-oxidant effects by the formation of hydroxyl radicals.24‐29 While it is established that prolonged MV promotes a 10-fold increase in HO-1 protein expression in the diaphragm,15 it is unknown whether this increase in HO-1 serves a pro-oxidant or an antioxidant function. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to determine whether increases in HO-1 serve to provide pro-oxidant or antioxidant functions in the diaphragm during MV. Moreover, we determined whether MV-induced HO-1 plays a role in MV-induced protease activation and atrophy in the diaphragm during MV. Based upon the probability that increased expression of HO-1 could increase cellular levels of reactive iron, we hypothesized that HO-1 acts as a pro-oxidant in the diaphragm during prolonged MV.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Experimental Design

Adult (4-6 months old) female Sprague-Dawley rats were used in these experiments. All experimental techniques were approved and performed according to guidelines set forth by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals were maintained on a 12-h-to-12-h light-dark cycle and provided food (American Institute of Nutrition 1993 recommended standard laboratory rodent diet) and water ad libitum throughout the experimental period. Rats were randomly assigned to one of the following groups (n = 8 per group): (1) an acutely anesthetized control group (CON), (2) a group that received 18 h of MV and saline solution (MVS), and (3) a group that received 18 h of MV and was treated with the HO-1 inhibitor chromium mesoporphyrin IX (CrMPIX) (MVI).

Control Animals

Animals in the control group were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg IP). After reaching a surgical plane of anesthesia, the animals were killed immediately, and one portion of the costal diaphragm was immediately frozen in Tissue-Tek imbedding medium (Sakura Finetek; Torrance, California) and stored at −80°C for histochemical analysis. The remainder of the costal diaphragm was rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for subsequent biochemical analyses.

Experimental Protocol of MV

Animals in the MVS and MVI groups were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg IP). After reaching a surgical plane of anesthesia, tracheostomies were performed on the animals using aseptic techniques and mechanically ventilated with a controlled pressure-driven ventilator (Servoventilator 300; Siemens; Bridgewater, New Jersey) for 18 h with the following settings: upper airway pressure limit, 20 cm H2O; pressure control level above positive end-expiratory pressure, 4 to 6 cm H2O; respiratory rate, 80 beats/ min; and positive end-expiratory pressure, 1.0 cm H2O. In general, we estimate that these ventilator settings result in a tidal volume of ~ 1 mL/100 g of body weight. Animals in the MVI group received a 5-μM/kg IP injection of CrMPIX immediately prior to MV. All surgical procedures were performed as previously described in detail.15 Briefly, cannulas were inserted into the carotid artery to permit continuous measurement of BP and the collection of periodic arterial blood samples during MV. Blood samples were analyzed for pH, Po2, and Pco2 using an electronic blood gas analyzer (GEM Premier 3000; Instrumentation Laboratory; Lexington, Massachusetts). If necessary, adjustments were made to the ventilator to ensure that arterial blood gas and pH measures were within the desired physiologic ranges. Pao2 was maintained at > 70 mm Hg throughout the experiment by adjustments in Fio2 (22%-25% oxygen). Cannulas were inserted into the jugular vein for the constant infusion of sodium pentobarbital (~ 10 mg/kg/h). Body temperature was maintained between 36°C and 37°C by using a recirculating heating blanket, and the heart rate was monitored via a lead II ECG. Continuous care during the MV protocol included lubricating the eyes, expressing the bladder, removing airway mucus, rotating the animal, and passive limb movement. Animals also received an IM injection of glycopyrrolate (0.04 mg/kg) every 2 hours during MV to reduce airway secretions. Following 18 h of MV, the animals were immediately killed, and diaphragm samples were stored as described previously.

Western Blot Analysis

Diaphragm samples were homogenized in a buffer containing 30 mM tris (hydroxymethyl) aminomethane hydrochloride (pH 7.5), 250 mM sucrose, 150 mM sodium chloride, 1.0 mM dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma; St. Louis, Missouri). Homogenates were centrifuged at 4°C for 12 min at 16,000g. After centrifugation, the supernatant fluid was collected, and Bradford protein assays were performed to determine protein content. Equal amounts of protein were loaded to gels, separated via polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The resulting membranes were then stained with Ponceau S stain and analyzed to ensure equal protein loading and transfer; then, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies directed against the protein of interest. Specifically, HO-1 was probed using a primary antibody obtained from Stressgen (OSA-111; Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania), and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) (#46545; Abcam; Cambridge, Massachusetts) was probed as a biomarker of oxidative stress. Also, expressions of caspase-3 (#9665; Cell Signaling; Carlsbad, California) and calpain (#30064; Santa Cruz; Santa Cruz, California) within diaphragm muscle from each experimental group were analyzed using the Western blot. Furthermore, the α-II spectrin-specific degradation products (ie, the 145-kDa calpain-specific and the 120-kDa caspase-3-specific cleavage products) were analyzed using the Western blot with an antibody obtained from Santa Cruz (#48382). Following exposure to secondary antibodies, the blots were imaged and analyzed using an Odyssey system (Li-Cor Biosciences; Lincoln, Nebraska).

HO Activity

HO activity in the diaphragm was determined as previously described by Badhwar et al.30 Briefly, diaphragms were homogenized in 0.1 M of potassium phosphate-buffered saline solution and centrifuged at 18,800g. Then, a reaction mixture was used that contained 120 μL of supernatant fluid, 0.1 M of potassium phosphate-buffered saline solution, 25 μM of hemin, and rat liver cytosol (as a source of biliverdin reductase). Subsequently, 0.4 mM nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate was added to initiate the reaction, and the samples were incubated in the dark at 37°C for 30 min. The reaction was terminated by placing the samples on ice. The amount of bilirubin produced was calculated as the difference in absorbance between 470 and 530 nm as read on a spectrophotometer using an extinction coefficient of 40 mM/cm2.

Total Glutathione

Total glutathione (GSH) content in the diaphragm was measured as a marker of redox status (ie, oxidative stress) using a commercially available kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Cayman Chemical; Ann Arbor, Michigan). Briefly, a section (~ 25 mg) of the costal diaphragm was homogenized at 1:30 (weight:volume) in 100 mM of phosphate buffer solution containing 1 mM of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and 0.05% bovine serum albumin. Samples were centrifuged at 10,000g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant fluid was deproteinated with an equal volume of metaphosphoric acid, centrifuged, and combined with 50 μL of triethanolamine per milliliter of supernatant fluid. Fifty microliters of deproteinated sample were reacted with the provided assay cocktail in the dark for 25 min. Absorbance was read at 405 nm. Standards were prepared using oxidized glutathione, which was reduced to 2-mol equivalents of GSH under the assay conditions, and concentrations were calculated based on this standard curve.

Myofiber Cross-sectional Area

To determine diaphragm muscle fiber cross-sectional areas, sections from frozen diaphragm samples were cut at 10 μm using a cryotome (Shandon Inc; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) and stained for fiber-type differentiation and cross-sectional area analysis as described previously.20 Briefly, muscle sections were stained with dystrophin (rabbit host, #RB-9024-R7; Laboratory Vision Corporation; Fremont, California) (to identify fiber membranes) and myosin heavy chain type 1 protein (mouse host, IgM isotype, A4.840; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank; Iowa City, Iowa) and myosin heavy chain type IIa protein (SC-71, mouse host, IgG isotype; a gift from Takao Sugiura, Yamaguchi University, Yamaguchi, Japan) to identify individual fiber types. The sections were then exposed to rhodamine red anti-rabbit secondary antibody (R6394; Molecular Probes; Eugene, Oregon), Alexa Fluro 350 goat anti-mouse IgM isotype-specific secondary antibody (AB1552; Molecular Probes), and Alexa Fluro 488 goat anti-mouse IgG isotype-specific secondary antibody (A11011; Molecular Probes) diluted in phosphate-buffered saline solution containing 0.5% Pierce Super Blocker (57535; Pierce; Rockford, Illinois) in a dark, humid chamber at room temperature for 1 h. Sections were then washed in phosphate-buffered saline solution and mounted using Vectashield (Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, California). Following staining, images were obtained at × 10 magnification and approximately 250 myofibers, which were chosen by the determination of no additional change in SD, and they were analyzed to determine myofiber cross-sectional area (μm2) using Scion Image software (Scion Technologies; Frederick, Maryland) by a blinded investigator.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons between groups were made using a one-way analysis of variance, and when appropriate, a Tukey honestly significant difference test was performed. Please note that when dependent measures were repeated over time, a repeated-measures analysis of variance was used to determine if group differences existed (eg, heart rate, arterial BP). Significance was established at P < .05.

Results

Systemic and Biologic Response to MV

Data for heart rate and systolic BP are shown in Table 1. Importantly, no significant differences existed between the experimental groups for heart rate or systolic BP at the beginning or at the completion of MV. Also, the Pao2 and Paco2 did not differ between groups at the onset or the completion of MV (Table 1). In addition, at the completion of the MV protocols, there were no visual abnormalities of the lungs or peritoneal cavity, no evidence of lung infarction, and no evidence of infection, indicating that our aseptic surgical technique was successful.

Table 1.

—Heart Rate, BP, Pao2, and Paco2 of Mechanically Ventilated Animals at the Beginning and at the Completion of the Experiments

| Experimental Groups |

||

| Physiologic Variables | 18 MVS | 18 MVI |

| At onset of MV (~ 30 min) | ||

| Heart rate, beats/min | 380 ± 9 | 390 ± 11 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 116 ± 3 | 118 ± 8 |

| Pao2, mm Hg | 74 ± 3 | 77 ± 4 |

| Paco2, mm Hg | 33 ± 2 | 37 ± 3 |

| At completion of MV (18 h) | ||

| Heart rate, beats/min | 354 ± 9 | 353 ± 11 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 76 ± 11a | 84 ± 21a |

| Pao2, mm Hg | 81 ± 3 | 77 ± 2 |

| Paco2, mm Hg | 37 ± 2 | 39 ± 2 |

No statistical differences existed between the two experimental groups at any time period. Values are mean ± SE. MV = mechanical ventilation; MVI = group that received 18 h of mechanical ventilation and was treated with the heme oxygenase-1 inhibitor chromium mesoporphyrin IX; MVS = group that received 18 h of MV and saline solution.

Values are different from those at onset of MV (P < .05).

Prolonged MV Promotes HO-1 Expression in the Diaphragm

Our prior work reveals that prolonged MV results in a large increase in HO-1 messenger RNA in the diaphragm.31 To determine whether this increase in messenger RNA results in a significant increase in HO-1 protein in the diaphragm following 18 h of MV, we used Western blots to quantify the levels of HO-1 protein in the diaphragm. Compared with those of the control group, the diaphragmatic HO-1 protein levels in the other two groups were increased ~10-fold during the 18 h of MV (Fig 1). The use of the HO-1 inhibitor CrMPIX did not prevent the MV-induced induction of HO-1 in the diaphragm. This is in agreement with a previous study that investigated the effect of CrMPIX in skeletal and cardiac tissues.32 Although CrMPIX does not prevent stress-induced expression of HO-1, it is well established that CrMPIX administration inhibits HO activity in a variety of tissues via competitive inhibition.32‐34 Importantly, we verified the efficacy of CrMPIX in inhibiting HO-1 activity in diaphragm muscle (Fig 2).

Figure 1.

A, Representative Ponceau S-stained membrane used to verify equal protein loading and transfer for Western blots. B, Fold changes (vs CON) of HO-1 protein abundance in diaphragm samples. Representative Western blot for HO-1 is shown above the graph. Values are mean ± SE. * = significantly different vs CON (P < .05). CON = anesthetized control group; HO = heme oxygenase; MVI = group that received 18 h of mechanical ventilation and was treated with the heme oxygenase-1 inhibitor chromium mesoporphyrin IX; MVS = group that received 18 h of MV and saline solution.

Figure 2.

Fold changes (vs CON) of HO-1 activity in diaphragm samples. Values are mean ± SE. * = significantly different vs CON and MVI (P < .05). See Figure 1 legend for expansion of abbreviations.

Elevated Levels of HO-1 Do Not Protect Against MV-Induced Oxidative Stress in the Diaphragm

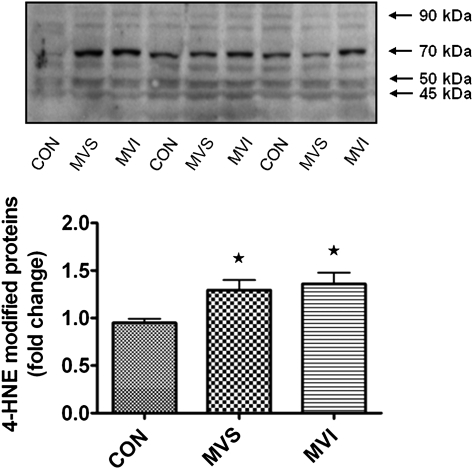

As discussed and reported previously,15 prolonged MV promotes large increases in the expression of HO-1 in the diaphragm. To determine whether HO-1 promotes or protects against MV-induced oxidative stress, we measured two biomarkers (GSH and 4-HNE) of oxidative stress in diaphragms from animals in the MVS group with and without HO-1 inhibition. GSH is the major nonezymatic antioxidant of the cell, and depletion of cellular GSH typically occurs during periods of oxidative stress. 4-HNE is an unsaturated α,β hydroxyalkenal that is generated during the lipid peroxidation cascade, and 4-HNE-protein conjugates are an excellent biomarker of oxidative stress. Our results indicate that prolonged MV resulted in a significant depletion of total GSH in diaphragms from the MVS group and that inhibition of HO-1 activity did not prevent the MV-induced depletion of diaphragmatic GSH levels (Fig 3). Further, as we have previously shown,18 MV resulted in a significant increase in 4-HNE-protein conjugates (ie, 100-40 kDa) in the diaphragm (Fig 4), and inhibition of HO-1 activity during MV did not increase or decrease the levels of 4-HNE-protein conjugates in the diaphragm. Collectively, these results suggest that HO-1 does not function as either a pro-oxidant or an antioxidant in the diaphragm during MV.

Figure 3.

Measurement of total GSH level in diaphragm muscle. No differences existed between MVS and MVI. Values are mean ± SE. * = significantly different vs CON (P < .05). GSH = glutathione; gww = gram wet weight. See Figure 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

Figure 4.

Measurement of 4-HNE protein conjugates in diaphragm muscle (ie, 100-40 kDa). Representative Western blot for 4-HNE protein conjugates is shown above the graph. Values are mean ± SE. * = significantly different vs CON (P < .05). 4-HNE = 4-hydroxynonenal. See Figure 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

HO-1 Does Not Participate in MV-Induced Calpain and Caspase-3 Activation in the Diaphragm

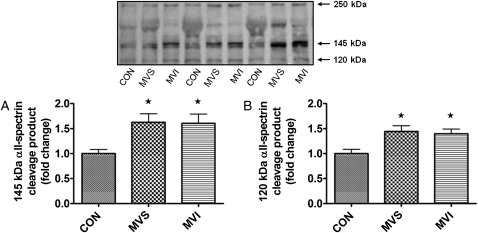

The diaphragmatic protein abundance of both calpain and caspase-3 proteins did not differ between groups (Fig 5). However, because oxidative stress has been linked to the activation of these proteases in skeletal muscle, we also determined whether HO-1 activity impacts the activation of both calpain and caspase-3 in the diaphragm during MV. To achieve this objective, we measured the activities of both calpain and caspase-3 using signature cleavage products of α-II spectrin. We also probed for α-II spectrin since it is a cytoskeletal structural protein that is present in several cell types, including skeletal muscle. During periods of increased calpain or caspase-3 activity, α-II spectrin breakdown exhibits signature cleavage products that can be used to detect cleavage by both calpain and caspase-3.35,36 Specifically, the intact form of α-II spectrin exists as a 250-kDa protein that upon degradation by calpain yields a 145-kDa degradation product, whereas degradation of α-II spectrin by caspase-3 produces a signature 120-kDa breakdown product.36 Following 18 h of MV, there was a significant increase in both calpain- and caspase-3-specific degradation products (ie, 145-kDa and 120-kDa bands, respectively) of α-II spectrin in the diaphragms of both the MVS and MVI groups (Fig 6), as we have previously reported.19 These results confirm that prolonged MV activates both calpain and caspase-3 in the diaphragm and that HO-1 activity does not contribute to the activation of calpain or caspase-3 in the diaphragm during MV.

Figure 5.

A, Measurement of caspase-3 protein abundance in diaphragm muscle. B, Measurement of calpain protein abundance in diaphragm muscle. Representative Western blots are shown above the graphs. Values are mean ± SE. See Figure 1 legend for expansion of the abbreviations.

Figure 6.

α-II Spectrin degradation product levels in diaphragm muscle. A, Fold changes (vs CON) of the 145-kDa (calpain-specific) α-II spectrin degradation product levels in diaphragm samples. B, Fold changes (vs CON) of 120-kDa (caspase-3-specific) α-II spectrin degradation product levels in diaphragm samples. Representative Western blot for the α-II spectrin degradation products is shown above the graph. Values are mean ± SE. * = significantly increased vs CON (P < .05). See Figure 1 legend for expansion of the abbreviations.

HO-1 Does Not Promote or Protect Against MV-Induced Diaphragmatic Atrophy

Because oxidative stress has been shown to promote MV-induced atrophy of diaphragm muscle fibers,7,37 we determined whether HO-1 contributes to MV-induced diaphragmatic atrophy. Compared with the control group, we observed a significant decrease in the cross-sectional area of diaphragmatic type 1, IIa, and IIb/x fibers following 18 h of MV in the other two groups (Fig 7), which agrees with previous data from our laboratory.14 Treatment of animals using the HO-1 inhibitor CrMPIX did not alter the MV-induced decrease in the cross-sectional area of any diaphragm fibers, indicating that HO-1 activation does not promote or protect against MV-induced diaphragmatic atrophy.

Figure 7.

Measurements of diaphragmatic fiber CSAs. A, Type 1 fiber CSA in the diaphragm. B, Type IIa fiber CSA in the diaphragm. C, Type IIb/x fiber CSA in the diaphragm. D, Representative photomicrographs of diaphragmatic fibers from CON, MVS, and MVI. Stains: type 1 (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole filter/blue), type IIa (fluorescein isothiocyanate filter/green), type IIb/x (black), and dystrophin (rhodamine filter/red) (original magnification × 10). Values are mean ± SE. * = significantly different vs CON (P < .05). CSA = cross-sectional area. See Figure 1 legend for expansion of the other abbreviations.

Discussion

Overview of Principal Findings

It is well established that prolonged MV results in a rapid onset of diaphragmatic atrophy and that MV-induced oxidative stress in the diaphragm is a requirement for MV-induced diaphragmatic wasting. Hence, understanding the mechanisms responsible for MV-induced oxidative stress in the diaphragm is important. In this regard, although it is clear that MV promotes an increase in HO-1 protein expression in the diaphragm, it is unknown whether HO-1 functions as a pro-oxidant or an antioxidant in diaphragm fibers. Therefore, these experiments addressed this important issue. Our results indicate that prolonged MV promotes HO-1 protein expression, oxidative stress, and atrophy in the diaphragm. However, inhibition of HO-1 activity did not protect against or exacerbate diaphragmatic oxidative injury, protease activation, or myofiber atrophy in the diaphragm during MV. Hence, these experiments provide the first evidence, to our knowledge, that HO-1 does not act as a pro-oxidant or an antioxidant in the diaphragm during MV. A discussion of these and other related issues follow.

Inhibition of HO-1 Activity Does Not Attenuate or Enhance MV-Induced Diaphragmatic Oxidative Stress

Prolonged MV is associated with a shift in the pro-oxidant-to-antioxidant balance in the diaphragm, resulting in increased protein oxidation and lipid peroxidation in this key inspiratory muscle.5,13,15 The diaphragmatic endogenous antioxidant system is intricate and involves both enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidants.15 In this regard, prolonged MV depletes diaphragmatic GSH stores and therefore reduces the nonenzymatic antioxidant capacity of the diaphragm.15

Our results indicate that prolonged MV resulted in an ~ 10-fold increase in the protein abundance of HO-1 in the diaphragm. Although HO-1 is postulated to contribute to redox balance in cells, there is uncertainty in the literature about whether overexpression of HO-1 is beneficial or deleterious to cells as the result of its reported actions as either a pro-oxidant or an antioxidant.27 In sepsis-related models of skeletal muscle injury, HO-1 has been shown to be effective in reducing oxidative stress and contractile dysfunction.32,38,39 Nonetheless, in theory, HO-1 can serve as a pro-oxidant by increasing the availability of free iron in the cell or as an antioxidant by producing both bilirubin and biliverdin. Following 18 h of MV, there was an ~ 40% increase in HO activity in diaphragm myofibers. In our experiments, we used a spectrophotometric assay to determine HO activity. Note, however, that this assay measures total bilirubin production and therefore does not distinguish between HO-1, HO-2, and HO-3 isoforms. Nonetheless, we and others have noted that the diaphragmatic levels of other HO isoforms (eg, HO-2) are extremely low in basal conditions,40 during MV (unpublished data) or during sepsis.38 Therefore, we predict that the small presence of HO-2 in the diaphragm would have a limited impact on the total HO activity in the diaphragm. To determine whether MV-induced HO-1 functions as a pro-oxidant or an antioxidant in the diaphragm during MV, we pharmacologically inhibited HO-1 activity using the HO-1 inhibitor CrMPIX. This inhibitor has a high specificity for HO-1 and does not inhibit some isoforms of nitric oxide synthase or soluble guanylate cyclase.41 Again, our data clearly indicate that a 10-fold increase in diaphragmatic levels of HO-1 does not protect or exacerbate MV-induced diaphragmatic oxidative injury.

HO-1 Does Not Protect Against MV-Induced Protease Activation in the Diaphragm

It is established that protease activation plays a major role in promoting disuse skeletal muscle atrophy.10,42,43 Moreover, in agreement with published reports in both human and animal models, prolonged MV resulted in activation of proteases in the diaphragm.12,19,20 In this regard, several studies have shown that antioxidant therapy during periods of skeletal muscle disuse can effectively decrease both oxidative stress and myofiber atrophy.7,37,44,45 Therefore, we determined whether inhibition of HO-1 activity influences MV-induced protease activation in the diaphragm. We focused our attention on calpain and caspase-3 because activation of these proteases can be a first step to initiate the cascade of events underlying skeletal muscle atrophy.43,46‐48 Indeed, our laboratory has shown that caspase-3 plays a critical role in skeletal muscle atrophy because pharmacologic inhibition of caspase-3 activity retards diaphragmatic atrophy during MV.37 Furthermore, the inhibition of calpain activity is also effective in attenuating diaphragmatic atrophy during prolonged MV.19

Our results reveal that 18 h of MV resulted in a significant increase in the activity of both calpain and caspase-3 in the diaphragm. However, inhibition of HO-1 activity did not influence the activation of either calpain or caspase-3 in the diaphragm during MV. These observations indicate that MV-induced HO-1 expression is not associated with the activation of these two proteases. Consistent with these results, our data also reveal that prolonged MV promotes atrophy in diaphragmatic type 1, type IIa, and type IIb/x fibers and that inhibition of HO-1 activity does not alter the magnitude of MV-induced diaphragmatic atrophy.

Conclusions

This study provides the first evidence, to our knowledge, that increased expression of HO-1 does not function as a pro-oxidant or an antioxidant in the diaphragm during the first 18 h of prolonged MV. Specifically, our results demonstrate that although HO-1 protein abundance in the diaphragm is increased 10-fold, inhibition of HO-1 activity does not increase or decrease MV-induced diaphragmatic oxidative stress. Furthermore, the inhibition of HO-1 activity in the diaphragm does not alter MV-induced protease (eg, calpain and caspase-3) activation and does not impact the magnitude of MV-induced diaphragmatic fiber atrophy.

Although the current findings do not support a protective or a harmful role for HO-1 in the diaphragm during prolonged MV, it is possible that the increased expression of HO-1 can contribute to other important signaling pathways involved in the MV-induced remodeling of the diaphragm. In this regard, the main biologic function of HO-1 is to avoid the accumulation of highly deleterious free heme (eg, not bound).49 However, several other aspects of HO-1 biology are likely to contribute to its broad effects in cellular protection and remodeling. As discussed previously, HO-1 degrades free heme to yield equimolar amounts of three products (ie, carbon monoxide, iron, and biliverdin). Over the past several years, it has become apparent that these three “arms” of the HO-1 system can act protectively in a variety of experimental models of disease.49 For example, growing evidence suggests that the HO-1-induced production of carbon monoxide may be of biologic importance in many cell types.50,51 Indeed, carbon monoxide has been linked to the activation of a variety of cellular-signaling pathways (eg, mitogen-activated kinases) that can produce cellular benefits or damage, depending upon the level of carbon monoxide exposure and pathway activation.51 Several authors have concluded that HO-1 expression contributes to the reestablishment of cellular homeostasis after a broad range of pathologic insults.49,51,52 For instance, overexpression of HO-1 has been postulated to provide protection against contraction-mediated muscle injury.53 Therefore, it is possible that the MV-induced increased expression of HO-1 could protect the diaphragm against contraction-induced injury during the weaning phase of MV. This is a testable hypothesis that is worthy of future research.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: Dr Falk: participated in the design of the study, collected and analyzed data, and cowrote the article.

Dr Kavazis: participated in the design of the study, collected and analyzed data, and cowrote the article.

Dr Whidden: participated in the design of the study and collected and analyzed data.

Ms Smuder: participated in the design of the study and collected and analyzed data.

Dr McClung: participated in the design of the study and collected and analyzed data.

Mr Hudson: collected and analyzed data.

Dr Powers: participated in the design of the study and cowrote the article.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST that no potential conflicts of interest exist with any companies/organizations whose products or services may be discussed in this article.

Abbreviations

- 4-HNE

4-hydroxynonenal

- CON

anesthetized control group

- CrMPIX

chromium mesoporphyrin IX

- GSH

glutathione

- HO

heme oxygenase

- MV

mechanical ventilation

- MVI

group that received 18 h of mechanical ventilation and was treated with the heme oxygenase-1 inhibitor chromium mesoporphyrin IX

- MVS

group that received 18 h of MV and saline solution

Footnotes

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians (http://www.chestpubs.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml).

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grant R01 HL072789, awarded to Dr Powers].

References

- 1.Jubran A. Critical illness and mechanical ventilation: effects on the diaphragm. Respir Care. 2006;51(9):1054–1064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esteban A, Alía I, Ibañez J, Benito S, Tobin MJ. The Spanish Lung Failure Collaborative Group Modes of mechanical ventilation and weaning. A national survey of Spanish hospitals. Chest. 1994;106(4):1188–1193. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.4.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boles JM, Bion J, Connors A, et al. Weaning from mechanical ventilation. Eur Respir J. 2007;29(5):1033–1056. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00010206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemaire F. Difficult weaning. Intensive Care Med. 1993;19(Suppl 2):S69–S73. doi: 10.1007/BF01708804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vassilakopoulos T. Ventilator-induced diaphragm dysfunction: the clinical relevance of animal models. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(1):7–16. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0866-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vassilakopoulos T, Zakynthinos S, Roussos C. Bench-to-bedside review: weaning failure—should we rest the respiratory muscles with controlled mechanical ventilation? Crit Care. 2006;10(1):204. doi: 10.1186/cc3917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Betters JL, Criswell DS, Shanely RA, et al. Trolox attenuates mechanical ventilation-induced diaphragmatic dysfunction and proteolysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(11):1179–1184. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200407-939OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeRuisseau KC, Kavazis AN, Deering MA, et al. Mechanical ventilation induces alterations of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in the diaphragm. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98(4):1314–1321. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00993.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gayan-Ramirez G, Decramer M. Effects of mechanical ventilation on diaphragm function and biology. Eur Respir J. 2002;20(6):1579–1586. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00063102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powers SK, Kavazis AN, DeRuisseau KC. Mechanisms of disuse muscle atrophy: role of oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288(2):R337–R344. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00469.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Powers SK, Kavazis AN, McClung JM. Oxidative stress and disuse muscle atrophy. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102(6):2389–2397. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01202.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine S, Nguyen T, Taylor N, et al. Rapid disuse atrophy of diaphragm fibers in mechanically ventilated humans. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(13):1327–1335. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zergeroglu MA, McKenzie MJ, Shanely RA, Van Gammeren D, DeRuisseau KC, Powers SK. Mechanical ventilation-induced oxidative stress in the diaphragm. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95(3):1116–1124. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00824.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shanely RA, Zergeroglu MA, Lennon SL, et al. Mechanical ventilation-induced diaphragmatic atrophy is associated with oxidative injury and increased proteolytic activity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(10):1369–1374. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200202-088OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falk DJ, Deruisseau KC, Van Gammeren DL, Deering MA, Kavazis AN, Powers SK. Mechanical ventilation promotes redox status alterations in the diaphragm. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101(4):1017–1024. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00104.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaber S, Sebbane M, Koechlin C, et al. Effects of short vs. prolonged mechanical ventilation on antioxidant systems in piglet diaphragm. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31(10):1427–1433. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2694-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Gammeren D, Falk DJ, DeRuisseau KC, Sellman JE, Decramer M, Powers SK. Reloading the diaphragm following mechanical ventilation does not promote injury. Chest. 2005;127(6):2204–2210. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.6.2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kavazis AN, Talbert EE, Smuder AJ, Hudson MB, Nelson WB, Powers SK. Mechanical ventilation induces diaphragmatic mitochondrial dysfunction and increased oxidant production. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46(6):842–850. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maes K, Testelmans D, Powers S, Decramer M, Gayan-Ramirez G. Leupeptin inhibits ventilator-induced diaphragm dysfunction in rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(11):1134–1138. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200609-1342OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McClung JM, Kavazis AN, DeRuisseau KC, et al. Caspase-3 regulation of diaphragm myonuclear domain during mechanical ventilation-induced atrophy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(2):150–159. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200601-142OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McClung JM, Van Gammeren D, Whidden MA, et al. Apocynin attenuates diaphragm oxidative stress and protease activation during prolonged mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(4):1373–1379. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819cef63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whidden MA, McClung JM, Falk DJ, et al. Xanthine oxidase contributes to mechanical ventilation-induced diaphragmatic oxidative stress and contractile dysfunction. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106(2):385–394. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91106.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keyse SM, Tyrrell RM. Heme oxygenase is the major 32-kDa stress protein induced in human skin fibroblasts by UVA radiation, hydrogen peroxide, and sodium arsenite. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(1):99–103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balla G, Jacob HS, Balla J, et al. Ferritin: a cytoprotective antioxidant strategem of endothelium. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(25):18148–18153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balla J, Jacob HS, Balla G, et al. Endothelial cell heme oxygenase and ferritin induction by heme proteins: a possible mechanism limiting shock damage. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1992;105:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nath KA, Balla G, Vercellotti GM, et al. Induction of heme oxygenase is a rapid, protective response in rhabdomyolysis in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1992;90(1):267–270. doi: 10.1172/JCI115847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryter SW, Tyrrell RM. The heme synthesis and degradation pathways: role in oxidant sensitivity. Heme oxygenase has both pro- and antioxidant properties. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28(2):289–309. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamb NJ, Quinlan GJ, Mumby S, Evans TW, Gutteridge JM. Haem oxygenase shows prooxidant activity in microsomal and cellular systems: implications for the release of low-molecular-mass iron. Biochem J. 1999;344(Pt 1):153–158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suttner DM, Dennery PA. Reversal of HO-1 related cytoprotection with increased expression is due to reactive iron. FASEB J. 1999;13(13):1800–1809. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.13.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Badhwar A, Bihari A, Dungey AA, et al. Protective mechanisms during ischemic tolerance in skeletal muscle. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36(3):371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeRuisseau KC, Shanely RA, Akunuri N, et al. Diaphragm unloading via controlled mechanical ventilation alters the gene expression profile. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(10):1267–1275. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200503-403OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Supinski GS, Callahan LA. Hemin prevents cardiac and diaphragm mitochondrial dysfunction in sepsis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40(1):127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andresen JJ, Shafi NI, Durante W, Bryan RM., Jr Effects of carbon monoxide and heme oxygenase inhibitors in cerebral vessels of rats and mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291(1):H223–H230. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00058.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mingone CJ, Ahmad M, Gupte SA, Chow JL, Wolin MS. Heme oxygenase-1 induction depletes heme and attenuates pulmonary artery relaxation and guanylate cyclase activation by nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294(3):H1244–H1250. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00846.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pike BR, Flint J, Dutta S, Johnson E, Wang KK, Hayes RL. Accumulation of non-erythroid alpha II-spectrin and calpain-cleaved alpha II-spectrin breakdown products in cerebrospinal fluid after traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurochem. 2001;78(6):1297–1306. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pike BR, Flint J, Dave JR, et al. Accumulation of calpain and caspase-3 proteolytic fragments of brain-derived alpha II-spectrin in cerebral spinal fluid after middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24(1):98–106. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000098520.11962.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McClung JM, Kavazis AN, Whidden MA, et al. Antioxidant administration attenuates mechanical ventilation-induced rat diaphragm muscle atrophy independent of protein kinase B (PKB Akt) signalling. J Physiol. 2007;585(Pt 1):203–215. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.141119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barreiro E, Comtois AS, Mohammed S, Lands LC, Hussain SN. Role of heme oxygenases in sepsis-induced diaphragmatic contractile dysfunction and oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283(2):L476–L484. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00495.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taillé C, Foresti R, Lanone S, et al. Protective role of heme oxygenases against endotoxin-induced diaphragmatic dysfunction in rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(3 Pt 1):753–761. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.3.2004202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grozdanovic Z, Gossrau R. Expression of heme oxygenase-2 (HO-2)-like immunoreactivity in rat tissues. Acta Histochem. 1996;98(2):203–214. doi: 10.1016/S0065-1281(96)80040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kinobe RT, Dercho RA, Nakatsu K. Inhibitors of the heme oxygenase-carbon monoxide system: on the doorstep of the clinic? Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;86(9):577–599. doi: 10.1139/y08-066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moylan JS, Reid MB. Oxidative stress, chronic disease, and muscle wasting. Muscle Nerve. 2007;35(4):411–429. doi: 10.1002/mus.20743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Powers SK, Kavazis AN, McClung JM. Oxidative stress and disuse muscle atrophy. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102(6):2389–2397. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01202.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Appell HJ, Duarte JA, Soares JM. Supplementation of vitamin E may attenuate skeletal muscle immobilization atrophy. Int J Sports Med. 1997;18(3):157–160. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-972612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Servais S, Letexier D, Favier R, Duchamp C, Desplanches D. Prevention of unloading-induced atrophy by vitamin E supplementation: links between oxidative stress and soleus muscle proteolysis? Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42(5):627–635. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taillandier D, Aurousseau E, Combaret L, Guezennec CY, Attaix D. Regulation of proteolysis during reloading of the unweighted soleus muscle. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35(5):665–675. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(03)00004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tidball JG, Spencer MJ. Expression of a calpastatin transgene slows muscle wasting and obviates changes in myosin isoform expression during murine muscle disuse. J Physiol. 2002;545(Pt 3):819–828. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.024935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Du J, Wang X, Miereles C, et al. Activation of caspase-3 is an initial step triggering accelerated muscle proteolysis in catabolic conditions. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(1):115–123. doi: 10.1172/JCI200418330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Soares MP, Bach FH. Heme oxygenase-1: from biology to therapeutic potential. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15(2):50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Piantadosi CA. Carbon monoxide, reactive oxygen signaling, and oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45(5):562–569. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ryter SW, Choi AM. Heme oxygenase-1/carbon monoxide: from metabolism to molecular therapy. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41(3):251–260. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0170TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pae HO, Kim EC, Chung HT. Integrative survival response evoked by heme oxygenase-1 and heme metabolites. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2008;42(3):197–203. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.2008029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McArdle F, Spiers S, Aldemir H, et al. Preconditioning of skeletal muscle against contraction-induced damage: the role of adaptations to oxidants in mice. J Physiol. 2004;561(Pt 1):233–244. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.069914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]