Abstract

Background:

Psychologic symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression are relatively common among family members of patients who die in the ICU. The patient-level risk factors for these family symptoms are not well understood but may help to target future interventions.

Methods:

We performed a cohort study of family members of patients who died in the ICU or within 30 h of ICU transfer. Outcomes included self-reported symptoms of PTSD and depression. Predictors included patient demographics and elements of palliative care.

Results:

Two hundred twenty-six patients had chart abstraction and family questionnaire data. Family members of older patients had lower scores for PTSD (P = .026). Family members that were present at the time of death (P = .021) and family members of patients with early family conferences (P = .012) reported higher symptoms of PTSD. When withdrawal of a ventilator was ordered, family members reported lower symptoms of depression (P = .033). There were no other patient characteristics or elements of palliative care associated with family symptoms.

Conclusions:

Family members of younger patients and those for whom mechanical ventilation is not withdrawn are at increased risk of psychologic symptoms and may represent an important group for intervention. Increased PTSD symptoms among family members present at the time of death may reflect a closer relationship with the patient or more involvement with the patient’s ICU care but also suggests that family should be offered the option of not being present.

Death is a common occurrence in the ICU, with approximately 20% of deaths in the United States occurring during or shortly after an ICU stay.1 These deaths have important implications for our health-care system. For example, symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression are common among family members of patients who die in the ICU, although the mechanism and risk factors for development of these symptoms are not well understood.2‐7 The potential risk factors are numerous. Family members are under great stress when a loved one is in the ICU. They may witness invasive treatments as well as unfamiliar medical procedures and devices. CPR preceding death is traumatic for family members, and the proportion of in-hospital deaths that are preceded by CPR is increasing in the United States.8 In addition, family members often are asked to assume the role of surrogate decision maker because the majority of patients in the ICU are not able to participate in medical decisions.3,9,10 This role also may increase stress for family members.

Previous studies have identified characteristics of family members, rather than patients, that are associated with increased symptoms of PTSD and depression among those whose loved one dies in the ICU.2,3,11‐13 Although these family characteristics are likely to be important, we hypothesize that there also may be patient-level characteristics associated with family members’ development of symptoms of PTSD and depression after the death of the patient. Potential patient-level characteristics include age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education level, and cause of death. These patient predictors of family symptoms may be easier to detect in a health-care system focused on patients rather than on family members. In addition, the care that is delivered to patients and their family members at the end of life may have significance in the development of or protection from symptoms of PTSD. For example, a randomized trial in France showed that a standardized family conference and a bereavement pamphlet significantly reduced the prevalence of symptoms of PTSD and depression among family members.4

The goal of this study was to identify patient characteristics and patient care factors that may be risk factors for the development of PTSD and depression among family members of patients who die in the ICU. These risk factors, once identified, could provide clinicians and researchers with insights into ways to improve patient care to prevent psychologic morbidity among family members.

Materials and Methods

Design

This report describes a cohort study associated with a cluster randomized trial of an interdisciplinary, quality improvement intervention, Integrating Palliative and Critical Care (IPACC).14,15 The IPACC study took place in 15 hospitals in Washington state. The current study included the 11 hospital sites that allowed an additional survey to participating family members. These 11 hospitals include three university-affiliated teaching hospitals, one community-based teaching hospital, and seven community-based nonteaching hospitals. This report presents data from a follow-up survey of family respondents to the IPACC study who indicated that we could contact them for future research.

Study Participants

In the IPACC study, all patients who were in the ICU for at least 6 h and who died in the ICU or within 30 h of transfer out of the ICU were identified through hospital admission, discharge, and transfer records. At one hospital, the mailed recruitment letter was sent to the legal next of kin listed in the medical record. At all others, the mailings were sent to the patient’s home and addressed to “the family of” the deceased patient. For the follow-up survey, only family members who returned questionnaire materials for the randomized trial and agreed to future contact were approached. Family members were surveyed a minimum of 6 months after the patient’s death. Prevalence of symptoms of PTSD and depression and family characteristics associated with these symptoms have been reported previously from this cohort,7 but we have not reported patient characteristics or patient-care characteristics associated with these symptoms among family members. Institutional review board approval was obtained for all procedures at all sites.

Outcome Measures

PTSD Checklist Civilian Version:

Symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of PTSD were assessed with the PTSD Checklist Civilian Version (PCL), a 17-item self-report questionnaire that elicits graded responses for the intrusive, avoidant, and arousal PTSD symptom clusters.16 A series of investigations have demonstrated the reliability and validity of the PCL across trauma-exposed populations.17‐19 Responses are recorded on a scale from not at all (1) through moderately (3) to extremely (5). Symptoms consistent with Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, diagnosis were determined by adherence to the recommended algorithm that considers a score of ≥ 3 a symptom and follows the diagnostic rules requiring at least one intrusive symptom, three avoidant symptoms, and two arousal symptoms.16 We used dichotomous scoring to describe the number of families meeting criteria for PTSD and continuous scoring to assess the association between predictor variables and the burden of psychologic symptoms.

Patient Health Questionnaire:

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-8 uses eight items from the PHQ-9 (excluding the item about thoughts that one would be better off dead or of hurting oneself in some way) and has been shown to be reliable and valid.20‐23 The PHQ-8 can be scored continuously by summing the values of each response, resulting in scores that range from 0 to 24 or dichotomously by using a cutoff value of 10.24 In this study, we used the continuous PHQ-8 score to assess the association of patient characteristics and elements of palliative care with the level of symptoms. We used the dichotomous scoring to describe the number of families meeting criteria for depression.

Predictors and Covariates

Patient Characteristics:

Patient characteristics were collected from medical records and death certificates. Chart abstraction was completed on all patients. Data abstractors were trained by two research abstraction trainers. Training included a minimum of 80 h of practice abstraction with instruction on the protocol, guided practice charts, and independent chart review followed by reconciliation with the research abstraction trainers. Training continued until the abstractors reached 95% agreement with the trainers. For ongoing quality control, a coreview of a 5% random sample of patients’ charts was done to ensure agreement of ≥ 95% on all 440 abstracted data elements. The state of Washington releases confidential electronic death certificate data linked by a patient identifier for research purposes. Death certificate data were used to provide data that were either unavailable or incomplete in the medical record (ie, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, and trauma or cancer as cause of death).

Elements of Palliative Care:

Elements of palliative care were identified from medical records and included aspects of care that have been previously defined in consensus documents as quality indicators.25,26 They included chart documentation of the following: family presence at death; family conferences in the first 72 h of ICU admission; involvement of a social worker; extubation prior to death; do not resuscitate order prior to death; symptom assessment, including pain and anxiety, in the last 24 h of life; involvement of a spiritual care provider; death after a decision to withdraw or withhold life-sustaining therapies; death without CPR; withdrawal of a mechanical ventilator; and palliative care consultations.25‐28

Covariates:

Family characteristics were derived from the family questionnaires. Covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity, length and type of relationship with the decedent, and education.

Data Analysis

To evaluate associations between predictors (ie, patient characteristics, elements of palliative care) and symptoms of PTSD and depression, we performed unadjusted and adjusted linear regression using the PCL and PHQ-8 scores as continuous outcome variables. In the model adjusted for patient characteristics, we chose a priori to adjust for all patient characteristics in the model hypothesized to be associated with the outcomes. In the adjusted models for elements of palliative care, we chose a priori to adjust for family member characteristics that have previously been found to be associated with symptoms of PTSD or depression, including sex, education, relationship to the patient, and years of knowing the patient.7 Because the PCL and PHQ-8 scores were nonnormally distributed, we used a restricted maximum likelihood estimator with adjusted standard errors. Patient characteristics were assessed dichotomously (sex, white race, trauma), continuously (age), categorically (marital status), or ordinally (education). All elements of palliative care were assessed dichotomously. Significance was reported at P ≤ .05.

Results

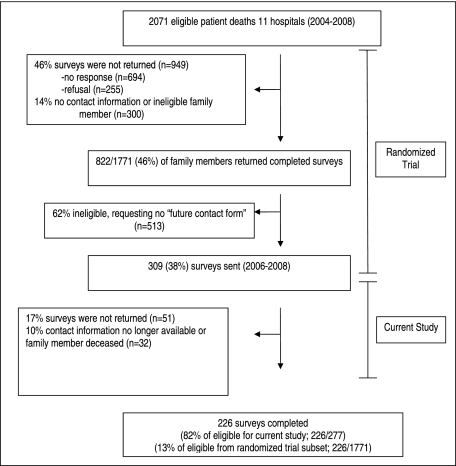

Survey data were collected between November 15, 2006, and November 10, 2008. A total of 226 family members returned follow-up questionnaires. This represents a response rate of 82% for the eligible family members who were mailed surveys for this study but only 13% of the patients identified as eligible in the prior randomized trial (Fig 1). As previously reported, the prevalence of PTSD among these family members was 14.0% (95% CI, 9.7%-19.3%), and the prevalence of depression among these family members was 18.4% (95% CI, 13.5%-24.1%). Scores on the PCL ranged from 17 to 76, with a median of 29 (interquartile range, 22-37). Scores on the PHQ-8 ranged 0 to 21, with a median of 4 (interquartile range, 1-8).7

Figure 1.

Development of the study cohort.

Baseline characteristics of the 226 family members who returned the survey and the 226 patients included in this cohort are summarized in Table 1. The majority of patients were men (58%), married (60%), non-Hispanic white (92%), and older (mean age, 70.5 years). About one-half had completed at least some college. As reported previously, patients with a responding family member were more likely to be non-Hispanic white, older, and married but did not differ in education.

Table 1.

—Demographic Characteristics of Family Members and Patients

| Characteristic | Family (n = 226) | Patient (n = 226) |

| Age, y | 59.7 ± 13.1 | 70.5 ± 14.7 |

| Female sex | 169 (74.8) | 95 (42.0) |

| White/non-Hispanic racea | 199 (88.4) | 207 (91.6) |

| Relationship to decedent | ||

| Spouse/partner | 110 (48.7) | … |

| Child | 83 (36.7) | … |

| Years associated with decedent | 46 (34-55) | … |

| Marital statusa | ||

| Never married | … | 16 (7.1) |

| Married | … | 135 (60.0) |

| Divorced | … | 25 (11.1) |

| Widowed | … | 49 (21.7) |

| Educationb | ||

| No formal education through eighth grade | 1 (0.4) | 14 (6.3) |

| Some high school | 4 (1.8) | 15 (6.7) |

| High school diploma or GED | 24 (10.6) | 81 (36.2) |

| Some college or trade school | 113 (50.0) | 56 (25.0) |

| Four-year college degree | 44 (19.5) | 37 (16.5) |

| Postcollege training | 40 (17.7) | 21 (9.4) |

| Cause of death | ||

| Trauma | … | 25 (11.0) |

| Cancer | … | 35 (15.4) |

| Other | … | 167 (73.6) |

Data are presented as No. (%), mean ± SD, or median (interquartile range). GED = general education development diploma.

One missing.

Two missing for patients.

There were few associations found between patient characteristics and family members’ symptoms of PTSD and depression. Patients who were older had family members with lower symptom scores for PTSD (P = .026). There were no other associations found between patient sex, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, or trauma or cancer as cause of death and either PTSD or depression symptoms (Table 2).

Table 2.

—Patient Characteristics Independently Associated With Symptoms of PTSD and Depression in Family Members

| PTSD (PCL) |

Depression (PHQ-8) |

|||

| Characteristic | β (95% CI) | P Value | β (95% CI) | P Value |

| Age | −0.20 (−0.37, −0.02) | .026a | −0.05 (−0.13, 0.03) | .201 |

| Female sex | −0.20 (−4.06, 4.45) | .928 | 0.56 (−1.19, 2.31) | .526 |

| White race | −0.05 (−6.89, 7.00) | .988 | −0.29 (−3.17, 2.59) | .844 |

| Education | ||||

| Some high school | Reference | Reference | ||

| High school | −0.91 (−5.87, 4.05) | .718 | −1.41 (−3.68, 0.87) | .224 |

| College or more | −0.65 (−5.86, 4.56) | .806 | −1.14 (−3.62, 1.33) | .362 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | Reference | Reference | ||

| Married | −5.89 (−16.19, 4.40) | .260 | −1.70 (−6.01, 2.60) | .436 |

| Divorced | 3.75 (−15.61, 8.10) | .533 | −2.47 (−6.88, 1.95) | .272 |

| Widowed | −6.57 (−17.67, 4.53) | .244 | −3.55 (−7.91, 0.81) | .110 |

| Cause of death | ||||

| Trauma | −0.81 (−6.54, 4.92) | .780 | −1.10 (−3.66, 1.45) | .396 |

| Cancer | 2.03 (−2.79, 6.85) | .407 | 1.18 (−0.70, 3.06) | .218 |

Multivariate model includes all characteristics from the table in the model as well as the following family characteristics: sex, education, relationship to patient, and years having known patient. The variables labeled as “Reference” are the variables with which the other variables in the same category are compared. PCL = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist Civilian Version; PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

Significant at P ≤ .05.

In the examination of associations between chart documentation of elements of palliative care and symptoms of PTSD in family members, we found that family members who were documented as present at the time of death (P = .021) and who had a family conference during the first 72 h of ICU hospitalization (P = .012) reported higher scores on the PCL for symptoms of PTSD. There were no other associations between chart documentation of delivery of palliative care and family symptoms of PTSD (Table 3).

Table 3.

—Elements of Palliative Care Associated With Symptoms of PTSD in Family Members

| Palliative Care Indicator, (No.)a | Families Meeting PTSD Criterion, No. (%) | β (95% CI)b | P Value |

| Family present at death (163) | 28 (17.2) | 4.90 (0.73, 9.06) | .021c |

| No family present at death (33) | 1 (3.0) | … | … |

| Family conference in first 72 h (161) | 26 (16.1) | 4.06 (0.88, 7.23) | .012c |

| No family conference in first 72 h (52) | 5 (9.6) | … | … |

| Social worker involved (105) | 17 (16.2) | 2.85 (−0.48, 6.18) | .093 |

| No social worker involved (107) | 14 (13.1) | … | … |

| Patient extubated prior to death (101) | 17 (16.8) | 2.80 (−2.09, 7.70) | .223 |

| Patient not extubated prior to death (59) | 5 (8.5) | … | … |

| DNR in chart (168) | 26 (15.5) | 0.97 (−3.11, 5.04) | .641 |

| No DNR in chart (39) | 4 (10.3) | … | … |

| Pain assessed in last 24 h of life (186) | 27 (14.5) | −0.01 (−4.14, 4.12) | .996 |

| No pain assessment in last 24 h of life (35) | 4 (11.4) | … | … |

| Spiritual care provider involved (73) | 20 (14.4) | −0.28 (−3.76, 3.21) | .875 |

| No spiritual care provider involved (139) | 11 (15.1) | … | … |

| Patient did not die in setting of full support (168) | 5 (12.5) | −0.99 (−6.23, 4.24) | .709 |

| Patient died in setting of full support (40) | 25 (14.9) | … | … |

| No CPR in last 24 h of life (188) | 3 (12.0) | −1.00 (−6.69, 4.68) | .728 |

| CPR in last 24 h of life (25) | 28 (14.9) | … | … |

| Ventilator withdrawal ordered (127) | 18 (14.2) | −1.51 (−5.16, 2.15) | .417 |

| No ventilator withdrawal ordered (80) | 12 (15.0) | … | … |

| Palliative care consult (15) | 1 (6.7) | −2.78 (−8.26, 2.70) | .318 |

| No palliative care consult (197) | 30 (15.2) | … | … |

DNR = do not resuscitate order. See Table 2 legend for expansion of other abbreviation.

Numbers for each palliative care indicator do not add to total because of missing data.

Adjusted for the following family characteristics: sex, education, relationship to patient, and years having known patient. Each palliative care indicator is not adjusted for other elements of palliative care.

Significant at P ≤ .05.

Table 4 shows the associations between chart documentation of delivery of palliative care and family symptoms of depression as scored by the PHQ-8. The only significant association was that family members of patients who had orders for withdrawal of a ventilator had significantly lower scores on the PHQ-8 (P = .033), indicating a lower burden of symptoms of depression.

Table 4.

—Elements of Palliative Care Associated With Symptoms of Depression in Family Members

| Palliative Care Indicator, (No.)a | Families Meeting Depression Criterion, No. (%) | β (95% CI)b | P Value |

| Family present at death (164) | 27 (16.5) | 1.60 (−0.26, 3.47) | .092 |

| No family present at death (34) | 2 (5.9) | … | … |

| Social worker involved (105) | 19 (17.1) | 1.34 (−0.07, 2.76) | .062 |

| No social worker involved (109) | 13 (11.9) | … | … |

| Patient extubated prior to death (101) | 18 (17.8) | 1.16 (−0.54, 2.86) | .181 |

| Patient not extubated prior to death (61) | 7 (11.5) | … | … |

| Family conference in first 72 h (162) | 27 (16.7) | 1.04 (−0.38, 2.47) | .150 |

| No family conference in first 72 h (63) | 5 (9.4) | … | … |

| No CPR in last 24 h of life (190) | 29 (15.3) | 0.29 (−1.71, 2.29) | .776 |

| CPR in last 24 h of life (25) | 3 (12.0) | … | … |

| Spiritual care provider involved (72) | 20 (14.1) | 0.28 (−1.25, 1.82) | .716 |

| No spiritual care provider involved (142) | 12 (16.7) | … | … |

| Pain assessed in last 24 h of life (188) | 28 (14.9) | −0.35 (−2.16, 1.47) | .706 |

| No pain assessment in the last 24 h or life (35) | 4 (11.4) | … | … |

| DNR in chart (170) | 26 (15.3) | −0.40 (−2.14, 1.35) | .654 |

| No DNR in chart (39) | 5 (12.8) | … | … |

| Patient did not die with full support (169) | 26 (15.4) | −0.87 (−2.80, 1.07) | .378 |

| Patient died with full support (41) | 5 (13.9) | … | … |

| Ventilator withdrawal ordered (127) | 18 (14.2) | −1.58 (−3.03, −0.13) | .033c |

| No ventilator withdrawal ordered (82) | 13 (15.9) | … | … |

| Palliative care consult (15) | 1 (6.7) | −1.61 (−3.82, 0.59) | .151 |

| No palliative care consult (199) | 31 (15.6) | … | … |

See Table 3 legend for expansion of abbreviation.

Numbers for each palliative care indicator do not add to total because of missing data.

Adjusted for the following family characteristics: sex, education, relationship to patient, and years having known patient. Each palliative care indicator is not adjusted for other elements of palliative care.

Significant at P ≤ .05.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that few patient characteristics or patient-care characteristics are significantly associated with symptoms of PTSD or depression among family members whose loved one dies in the ICU. We did find a significant association between patient age and PTSD symptoms, with families of older patients reporting fewer symptoms. Interestingly, family member age has not been associated previously with symptoms of PTSD, suggesting that it is the patient age that is relevant and that deaths of younger patients place family members at higher risk.28 Prior studies have shown only a few consistent family characteristics associated with increased risk of psychologic symptoms, including female sex and active role in medical decision making.3,7 Overall, there have been few patient or family characteristics that would accurately predict family members’ risk for development of psychologic symptoms after a patient’s death in the ICU, and therefore, it seems unlikely that interventions will be able to effectively target those at highest risk.

We also found few associations between chart documentation of the delivery of palliative care and symptoms of PTSD and depression in family members. When family conferences were documented as occurring early in the patient’s ICU stay, family members reported increased symptoms of PTSD. We suspect that this is not a result of the family conference itself, as family conferences and clinician communication previously have been shown to be associated with decreased psychologic morbidity for family members.29,30 A more likely explanation may be that the patients and families for whom early conferences are conducted may be facing challenging circumstances, such as patients with especially poor prognoses at the time of admission or sudden, unexpected illness. Additionally, the clinical team may identify those patients with complicated medical or family situations for earlier conferences. Unfortunately, our data do not allow us to further investigate these hypotheses.

We also found that family members who were present at the time of death reported higher symptoms of PTSD. It is possible that the family members who choose to or are able to be present at the time of death have a closer relationship to the patient, and therefore, this finding may be a marker for a quality of relationship that is strong. However, we believe it important to consider that being present at the bedside at the time of death is not the right choice for every family member and may be a particularly traumatic piece of the ICU dying experience that not every family member should experience. We believe that this highlights the importance of counseling family members about the dying experience in the ICU and allowing each family member to make choices most appropriate for them.

Finally, we found that family members reported fewer symptoms of depression when withdrawal of the ventilator was ordered. Although we did not find other associations suggesting that delivery of palliative care resulted in fewer symptoms of depression, this finding is in line with our hypothesis that earlier delivery of quality palliative care and preparation of the family for impending death, as often occurs with terminal withdrawal of life-sustaining therapies such as mechanical ventilation, reduces or protects against the development of symptoms of depression.

There are several limitations to our study. First, our response rate is relatively low. Although 82% of family members who were eligible for this follow-up study participated, only 13% of all patients eligible from the original randomized trial had a family member who participated in this study. This relatively low response rate from the original cohort introduces the potential for response bias. We have previously shown that patients of family members who do not respond to surveys are more likely to be nonwhite and younger and less likely to receive elements of palliative care in the ICU than patients of family members who do respond.31 If increased access to or delivery of palliative care is associated with decreased symptoms of PTSD and depression,4 this would suggest that our sample may overestimate the quality of palliative care and, consequently, underestimate the burden of these psychologic symptoms. Nonetheless, we believe that these results still provide useful information for researchers and clinicians. Further research is needed to identify ways to increase survey response rates for this type of research. Second, although self-report measures provide valid data on respondents’ perceptions of their emotional experiences, they may not provide the same assessments of psychologic states as clinical interviews or assessments. Therefore, future studies interested in identifying predictors of psychologic disease rather than symptoms will need to use clinical measures of PTSD and depression. Finally, we were not able to measure the baseline burden of family members’ psychologic symptoms prior to the patient’s critical illness and, therefore, could not assess the burden of symptoms that are directly due to the critical illness and the care of critically ill patients.

We identified only one patient characteristic that was associated with family members’ symptoms of PTSD after death of a loved one in the ICU, suggesting that patient characteristics will not be useful for accurately identifying family members at greatest risk for these symptoms. Prior research examining family characteristics associated with these symptoms similarly identified few risk factors but did not provide an accurate way to predict those at highest risk.2‐7 Future research is needed to identify family members at the greatest risk and, therefore, most likely to benefit from intervention. We did find that family members of patients dying without terminal withdrawal of life support were at increased risk for psychologic symptoms, and this group may be important for further evaluation and potential early intervention. Additionally, our finding that family members present at time of death have higher symptoms of PTSD suggests that it may be important to counsel family members accordingly and to allow each individual to make the choice that is best for him or her.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: Dr Kross had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Dr Kross: contributed to the study concept and design; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; statistical analysis; administrative, technical, and material support; drafting of the manuscript; and critical review of the manuscript.

Dr Engelberg: contributed to the study concept and design; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; statistical analysis and study supervision; administrative, technical, and material support; and critical review of the manuscript.

Dr Gries: contributed to the study concept and design; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; administrative, technical, and material support; and critical review of the manuscript.

Ms Nielsen: contributed to the study concept and design; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; administrative, technical, and material support; and critical review of the manuscript.

Dr Zatzick: contributed to the study concept and design and critical review of the manuscript.

Dr Curtis: contributed to the study concept and design; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; statistical analysis; administrative, technical, and material support; and critical review of the manuscript. He had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST that no potential conflicts of interest exist with any companies/organizations whose products or services may be discussed in this article.

Abbreviations

- IPACC

Integrating Palliative and Critical Care

- PCL

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist Civilian Version

- PHQ

Patient Health Questionnaire

- PTSD

posttraumatic stress disorder

Footnotes

For editorial comment see page 743.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research [R01NR05226] and by a fellowship grant from the American Lung Association [RT-70808-N]. This research was performed at Harborview Medical Center, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians (http://www.chestpubs.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml).

References

- 1.Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation ICU End-Of-Life Peer Group Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(3):638–643. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114816.62331.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson WG, Arnold RM, Angus DC, Bryce CL. Posttraumatic stress and complicated grief in family members of patients in the intensive care unit. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(11):1871–1876. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0770-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. FAMIREA Study Group Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):987–994. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):469–478. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pochard F, Azoulay E, Chevret S, et al. French FAMIREA Group Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients: ethical hypothesis regarding decision-making capacity. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(10):1893–1897. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel MD, Hayes E, Vanderwerker LC, Loseth DB, Prigerson HG. Psychiatric illness in the next of kin of patients who die in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(6):1722–1728. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318174da72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gries CJ, Engelberg RA, Kross EK, et al. Predictors of symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in family members after patient death in the intensive care unit. Chest. 2010;137(2):280–287. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehlenbach WJ, Barnato AE, Curtis JR, et al. Epidemiologic study of in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(1):22–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen LM, McCue JD, Green GM. Do clinical and formal assessments of the capacity of patients in the intensive care unit to make decisions agree? Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(21):2481–2485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrand E, Bachoud-Levi AC, Rodrigues M, Maggiore S, Brun-Buisson C, Lemaire F. Decision-making capacity and surrogate designation in French ICU patients. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(8):1360–1364. doi: 10.1007/s001340100982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cameron JI, Herridge MS, Tansey CM, McAndrews MP, Cheung AM. Well-being in informal caregivers of survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(1):81–86. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000190428.71765.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones C, Skirrow P, Griffiths RD, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder-related symptoms in relatives of patients following intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(3):456–460. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Pelt DC, Milbrandt EB, Qin L, et al. Informal caregiver burden among survivors of prolonged mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(2):167–173. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-493OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curtis JR, Treece PD, Nielsen EL, et al. Integrating palliative and critical care: evaluation of a quality-improvement intervention. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(3):269–275. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-272OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Treece PD, Engelberg RA, Shannon SE, et al. Integrating palliative and critical care: description of an intervention. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(11 suppl):S380–S387. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237045.12925.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weathers F, Ford J. Psychometric review of PTSD checklist (PCL-C, PCL-S, PCL-M, PCL-PR) In: Stamm BH, editor. Measurement of Stress, Trauma and Adaptation. Lutherville, MD: Sidran Press; 1996. pp. 250–251. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) Behav Res Ther. 1996;34(8):669–673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dobie DJ, Kivlahan DR, Maynard C, et al. Screening for post-traumatic stress disorder in female Veteran’s Affairs patients: validation of the PTSD checklist. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24(6):367–374. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(02)00207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker EA, Newman E, Dobie DJ, Ciechanowski P, Katon W. Validation of the PTSD checklist in an HMO sample of women. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24(6):375–380. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(02)00203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Löwe B, Kroenke K, Herzog W, Gräfe K. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) J Affect Disord. 2004;81(1):61–66. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Löwe B, Spitzer RL, Gräfe K, et al. Comparative validity of three screening questionnaires for DSM-IV depressive disorders and physicians’ diagnoses. J Affect Disord. 2004;78(2):131–140. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Löwe B, Schenkel I, Carney-Doebbeling C, Göbel C. Responsiveness of the PHQ-9 to psychopharmacological depression treatment. Psychosomatics. 2006;47(1):62–67. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, Braehler E. Validity of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(1):71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clarke EB, Curtis JR, Luce JM, et al. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Critical Care End-Of-Life Peer Workgroup Members Quality indicators for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(9):2255–2262. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000084849.96385.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mularski RA, Curtis JR, Billings JA, et al. Proposed quality measures for palliative care in the critically ill: a consensus from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Critical Care Workgroup. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(11 suppl):S404–S411. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000242910.00801.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glavan BJ, Engelberg RA, Downey L, Curtis JR. Using the medical record to evaluate the quality of end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(4):1138–1146. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318168f301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gries CJ, Curtis JR, Wall RJ, Engelberg RA. Family member satisfaction with end-of-life decision making in the ICU. Chest. 2008;133(3):704–712. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDonagh JR, Elliott TB, Engelberg RA, et al. Family satisfaction with family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: increased proportion of family speech is associated with increased satisfaction. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(7):1484–1488. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000127262.16690.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stapleton RD, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Goss CH, Curtis JR. Clinician statements and family satisfaction with family conferences in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(6):1679–1685. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000218409.58256.AA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kross EK, Engelberg RA, Shannon SE, Curtis JR. Potential for response bias in family surveys about end-of-life care in the ICU. Chest. 2009;136(6):1496–1502. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]