Abstract

Functional imaging studies demonstrate that motor imagery activates multiple structures in the human forebrain. We now show that phantom movements in an amputee and imagined movements in intact subjects elicit responses from neurons in several human thalamic nuclei. These include the somatic sensory nucleus receiving input from the periphery (ventral caudal – Vc), and the motor nuclei receiving input from the cerebellum (ventral intermediate -Vim) and the basal ganglia (ventral oral posterior - Vop). Seven neurons in the amputee demonstrated phantom movement-related activity (3 Vim, 2 Vop, and 2 Vc). Additionally, seven neurons in a group of three controls demonstrated motor imagery-related activity (4 Vim, and 3 Vop). These studies were performed during single neuron recording sessions in patients undergoing therapeutic treatment of phantom pain, tremor, and chronic pain conditions by thalamic stimulation. The activity of neurons in these sensory and motor nuclei respectively may encode the expected sensory consequences and the dynamics of planned movements.

Keywords: Motor control, Neurophysiology, Thalamus, Electrophysiology, Neuroanatomy

Introduction

Human motor imagery, including imitated, observed, and imagined movements, or phantom movements in amputees, can cause changes in bloodflow signals (PET) or blood oxygen level dependent signals (fMRI BOLD) in the cerebellum, basal ganglia [1], motor cortex and the supplementary motor cortical area (SMA) [2]. Somatosensory evoked potentials (SEPs) derived from the cortex of amputated patients have been studied during stimulation of truncated nerves and interpreted to indicate preservation of some input to the cortex [3]. However, specific reductions in the thalamic gray matter of amputees raise questions regarding the significance of the remaining input from the thalamus to the cortex [4]. Direct thalamic neuronal activity related to phantom movements in amputees or imagined movements in intact humans has not previously been described, to our knowledge.

Previously, in a subject suffering a right hand amputation, Ersland et al. demonstrated BOLD signal responses (1.5 years after injury) in contralateral primary motor cortex which were specifically related to phantom imagery of finger tapping of the amputated side [5]. Ramachandran et al. describe a patient with a left arm amputation (23 years after injury) with a significant reorganization of the sensory homunculus [6]. Touching the subject’s face evoked sensations in the phantom, and this finding was dependent on volitional phantom movement whereby movement shifted the sensory map on the face dynamically. The neural substrate for this fast plasticity remains unknown, although it might imply the uncovering of present but silent synapses [6].

Recently Kühn et al. recorded activity related to motor imagery via local field potential recordings in the subthalamic nucleus during surgery for Parkinson’s disease [7]. The presence of thalamic neural activity correlated with phantom movements would be evidence in humans of an enduring subcortical copy of planned movements. We have now recorded human single neuron activity related to movement during awake thalamic surgery for the treatment of phantom pain in an amputee (phantom movements), or for the treatment of tremor and neuropathic pain (controls – imagined movements).

Methods

Patients and Protocol

Recordings were made during the physiologic localization which preceded a stereotactic operation in a 39 year-old man with phantom limb pain (patient 398), twenty years after an amputation of the arm just below the shoulder (Figure 1) [8]. We also studied three control patients - two with tremor (74 year-old man - 409, and a 38 year-old woman – 407) and one with chronic pain (62 year-old woman - 404). In the amputee one trajectory (pass 3, P3) passed through the presumed representation of the phantom (the cellular responses are described below), and two trajectories (passes 1 and 2, P1 and P2) through regions not including the phantom representation in Vc.

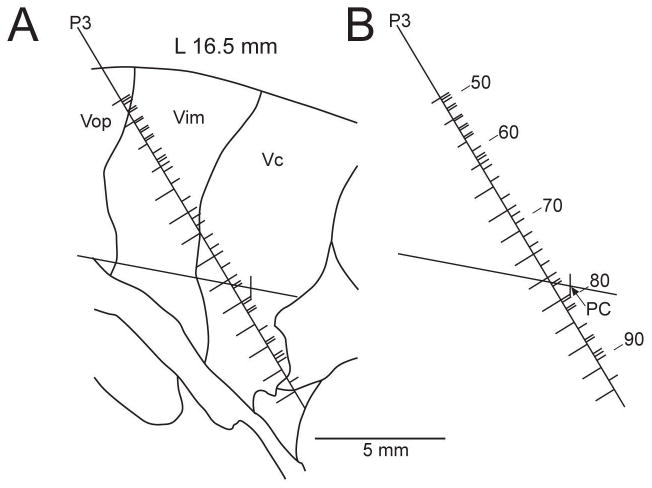

Figure 1.

Map of trajectory P3 in the region of the Vc in a 39 year-old man with phantom limb pain (patient 398). A: Position of trajectory P3 relative to nuclear boundaries as predicted from the position of the anterior commissure-posterior commissure (AC-PC) line in the sagittal plane, 16.5 mm lateral to midline. The AC-PC line is the solid, approximately horizontal line in panels A and B. PC is indicated in B and is represented by the vertical tic along the AC-PC line in A. The microelectrode trajectory is represented by the solid, oblique line. B: Location of the neurons and microstimulation sites along trajectory P3. The locations of microstimulation sites are indicated by tics to the left of the trajectory in B, while the locations of recorded neurons are indicated by tics to the right of the trajectory, neurons 50, 60, 70, 80, and 90 are labelled. Microstimulation sites at which a response was evoked are indicated by long tics, while those without a response are indicated by short tics.

The operative, microelectrode and analytic techniques for these human recordings have been published previously [9,10]. Most of the recordings took place within the ventral caudal (Vc), ventral intermediate (Vim), and ventral oral posterior (Vop) subnuclei. These are primarily the respective relay regions for somatic sensory input from the periphery (Vc), cerebellar input (Vim), and basal ganglia input (Vop) [11].

Recording Technique

The recordings identified the presence of sensory neurons which responded to either cutaneous stimuli (light touch, tapping of skin, pressure to skin), or to deep stimuli (joint movement, deep pressure to muscle, ligament/tendons). The anterior boundary of the region where sensory neurons were found in the majority defined the anterior border of Vc. This boundary was then used to predict the location of Vim and Vop which are adjacent anteriorly (Figure 1). In the amputee, Vc was defined as the region where stimulation at the majority of sites evoked cutaneous sensations at ≤ 25 μA (typical threshold used clinically [10]), because many neurons did not have receptive fields (RFs).

Imagery Task

Neuronal activity was examined for all recorded neurons during active closing and opening of the fist, flexion and extension of the wrist and elbow, and shoulder elevation and flexion, all cued by verbal commands [9]. Subjects were studied while performing real movements in response to a verbal command cue such as ‘make a fist’. Imaginary movements were carried out at each joint in their upper extremity on a command such as ‘imagine that you are making a fist without moving’. Phantom movements were carried out in response to commands such as ‘make a fist with the phantom’.

EMG activity was monitored from flexors and extensors of the wrist and elbow which confirmed the visual evidence of absence of movement during imaginary movements. All data was stored relative to the completion of the digitized auditory command (binwidth , 500 ms) two seconds (4 bins) before to eight seconds (16 bins) after the cue (CED Spike 2, Cambridge UK). A significant increase or decrease in firing rate (a response) was defined by a change greater than pre-command mean ± two standard deviations for three successive bins which implies a p<0.01 level of significance.

Results

A total of 283 neurons were studied during sensory stimulation and all types of movements, 166 in controls and 117 in the amputee. Across all nuclei, 135 neurons were studied during multiple real and imagined/phantom movements in the amputee (n=94) and controls (n=41) (see Figure 2). The proportion of neurons with activity related to any type of movement was more common for all sites in the controls (11/41) than in the amputee (9/94, p=0.02, Chi square). The proportion of neurons responding during imagined movements (7/41, 17%) was not statistically different than that responding during phantom movements (7/94, 7%, p=0.17, Chi square). All three of the control patients demonstrated motor imagery related activity in identified cells (Subject 404 - 3/9, 33%; Subject 407 - 2/10, 20%; Subject 409 - 2/22, 9%), these proportions are not statistically different than that occurring in the amputee related to phantom movement, however the number of cells involved is too small for inferring uniformity across the population.

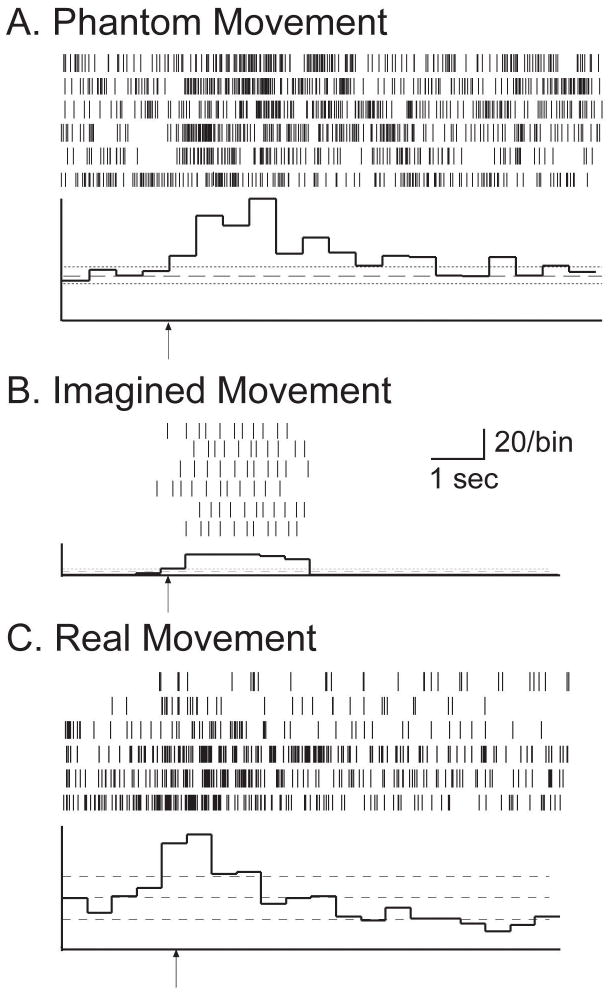

Figure 2.

Thalamic neurons responding during the phantom, imagined, and real movements of ‘making a fist’ in post-amputation (A) and an intact patient (Patient 407, essential tremor) (B, C). The arrow in each diagram represents completion of the verbal command. Horizontal lines represent +/− 2 SD from the mean of baseline bins. Panel A represents a neuron responding to imagining making a fist in the post-amputation patient. The histogram in B represents a neuron in Patient 407 responding to the motor imagery of making a fist, and in C a neuron responding to the real motor activity of making a fist.

Thalamic Sensory Nucleus (Vc)

The neuronal activity was characterized by the part of the body where peripheral stimulation (touch, stroking, pressure) evoked neuronal responses (receptive fields -RFs). Thalamic stimulation sites were also characterized by the location of sensations evoked by stimulation (projected fields- PFs). In Vc, cells with RFs were less common along trajectory P3 in the amputee, the presumed representation of the phantom (0/15), than along trajectories P1 and P2 through the representation of other parts of the body (17/21, p=0.0001 Fisher). In Vc, stimulation sites in the presumed phantom representation (trajectory P3) had PFs representing only one body part, e.g. one finger versus the whole hand or forearm with hand [8], less commonly (P3, 2/13) than in the other two trajectories (P1 and P2: 16/25, p=0.006 Fisher). This implies in the amputee either a degradation in function, or a reorganization of Vc characterized by a decrease in the number of neurons with RFs, in the number of stimulation sites with PFs, and by a decrease in size of the PF.

In the presumed representation of the phantom (P3), 3/13 neurons studied in Vc responded during movement (real or phantom). One neuron responded with real movement, one during phantom movement, and one during both phantom and real upper extremity movements. The two neurons responding during real shoulder movements (Table 1: 398-77 and -78) did not have cutaneous or deep RFs, and microstimulation evoked sensations did not include the shoulder. Therefore, it is unlikely that this activity was the result of sensory input resulting from movement.

Table 1.

Description of each neuron including identifier, response to real movements and imaginary movements, location and whether the response was excitatory or inhibitory.

| Neuron | Real Movements | Imagined/phantom Movements | Loc | Stimulation Response (current) | Cutaneous RF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 398-35-2 | Elbow extension | Vim | Roof of mouth sensation (40μA) | Face | |

| 398-35-1 | Shoulder extension | Vim | Roof of mouth sensation (40 μA) | Face | |

| 398-6 | Fist | Vim | NR | Intra-oral | |

| 398-69 | Open hand | Vim | Head sensation (30 μA) | Arm | |

| 398-1-2 | Fist/open hand | Vop | NR | Intra-oral | |

| 398-1-1 | Fist/biceps | Vop | NR | Intra-oral | |

| 398-77 | Shoulder extension | Vc | Hand, head, chest, forearm sensation (5 μA) | None | |

| 398-78 | shoulder extension | Fist/biceps/Elbow extension | Vc | Hand, head, chest, forearm sensation (5 μA) | None |

| 398-66 | Fist | Vcpor | Rt. hand forearm sensation (5 μA) | None | |

| 407-1-1 | Fist/open hand | Fist/open hand | Vim | Index finger movement (50 μA) | Arm |

| 407-1-2 | Fist | Fist/open hand | Vim | Index finger movement (50 μA) | Arm |

| 407-2 | Fist/elbow extension | Vim | NR | Arm | |

| 407-4-2 | Fist | Vop | NR | Arm | |

| 404-1 | Fist | Vop | NR | None | |

| 404-2-1 | Fist/biceps | Biceps/elbow extension | Vim | NR | None |

| 404-2-2 | Fist | Fist | Vim | NR | None |

| 404-3-2 | Open mouth | Vim | Decreased arm pain (40μA) | None | |

| 409-1 tremor/pain | Open hand | Vop | NR | Arm | |

| 409-2 | Biceps/elbow extension | Biceps | Vop | NR | Arm |

| 409-4 | Elbow extension | Fist/elbow extension | Vop | NR | Arm |

Conventions: Inhibitory in bold. Excitatory in plane typeface, No response–NR. Right column shows the majority cutaneous RF for the sagittal plane.

Thalamic Motor Nuclei (Vim and Vop)

The proportion of neurons across all subjects with activity related to any type of movement (real, imagined, or phantom) were not statistically different in Vim (12/68) compared to Vop (5/37) or Vc (3/13, p=0.7116). However, the ratio of movement-related neurons in Vim and Vop was higher in controls (11/33) versus P3 in the amputee (1/21, p=0.02 Fisher), although this number was not statistically different than that for all trajectories in the amputee (P1, P2, P3: 6/72, p>0.05 Chi square). In our sample, the proportion of neurons with activity related to real movements of the shoulder in the amputee was significantly greater (3/3, p=0.0035 Fisher) than that in the controls (0/10). Controls had a larger proportion of neurons with deep sensory arm RFs (19/94) than in the amputee shoulder (0/63, p=0.05 Fisher). This again implies an alteration in function or a reorganization of Vim and Vop characterized byan increase in the proportion of neurons with activity related to real movements of the shoulder and by a decrease in the number of cells with deep RFs due to the amputation.

In Vim, the proportion of neurons responding during imagined/phantom movements was significantly higher in controls versus all trajectories in the amputee (4/10 vs 2/52–P1, P2, P3 − p=0.005 Fisher), or versus the presumed representation of the phantom (P3) (4/10 vs 0/11, p=0.035 Fisher). In Vop, the proportion of such neurons was not significantly different between controls (3/25–12%) versus all trajectories in the amputee (2/13, 0%, NS Fisher) or versus trajectory P3 (0/6–0%, NS). Therefore, motor activity was altered in the amputee Vim, as indicated by a decrease in the number of neurons with activity related to active movements.

Parameters of Movement-related Activity

Significant movement-related neuronal activity was predominantly excitatory (+ sign, activity increasing) (29/37, 78%), and had the same sign during all different movement types in any individual neuron, except neuron 398-78 in the amputee (Table 1). The change in firing rates for different movements had the same sign within all cells examined, which is more common than expected if the signs occurred randomly for different movements within cells (p<0.02, combinatorial). Movement-related activity for neurons in Vim and Vop of controls and the amputee occurred about joints somatotopically appropriate for the upper extremity PFs in Vc on the same trajectory [9]. Although this study does not offer the direct comparison of activity evoked by motor imagery and phantom movements in a given subject, the above results do suggest that the neuronal activity related to imagined movement could be encoded in the same durable motor circuits which generate activity related to phantom movements in the amputee.

Discussion

These results demonstrate an alteration in function of thalamic motor or sensory nuclei in the amputee, as reflected by the smaller proportion of neurons responding during movement or with cutaneous or deep RFs. The size of the PFs was larger in Vc of the amputee, consistent with previous studies [12]. The neurons responding during phantom movements may correspond to those responding during imagined movements, given the similarities in incidence, somatotopy and latency of movement-related activity. Neither the duration nor the latency of onset of movement-related activity was significantly different between imagined and phantom movements (p>0.4, df=2, analysis of variance), although the timing resolution of the latency measurement is limited by the use of verbal commands.

Data Interpretation and Limitations

Although, it is possible that the phantom related cellular activity is subserved by the same neural circuitry as motor imagery related activity in normals, there might be alternative explanations. Motor imagery clearly incorporates a conscious block point in order to prevent real muscle activity from occurring, but we are unable to probe this with the amputee. The amputee might be activating the normal motor circuitry to move the phantom representation, without any conscious block occurring. Without the presence of the muscle end organ, the two situations would appear similar.

Additionally, it is not clear that our description of the thalamic regions showing activity correlated with phantom movements should actually be referred to as the phantom representation. This thalamic region might be contained in areas of the thalamus previously receiving somatosensory input from the amputated portions of the limb. The phantom representation would not necessarily overlap this, and could utilize additional surrounding or contralateral circuitry[13]. Furthermore, the electrophysiologic and stereotactic methods used to identify the thalamic subnuclei have been well described previously[10,11], but this may not hold in the phantom situation.

In this work, we study specifically the motor representations of the phantom which has not been well studied (most prior research has focused on phantom sensations), and in general the neural substrate for phantom motor sensations might involve more extended circuitry [14]. The reorganization effects seen in the thalamic subnuclei could also be interpreted as simply degradation in function caused by deafferentation, however one might expect increases in PF sizes to occur due to the higher levels of current required to activate neighboring excitatory structures. This is not observed in our data.

Possible Role of Imagery Activity

The movement-related activity of neurons in Vc was independent of sensory input and perception as measured by RFs and PFs at the recording site. In addition, the thalamic activity related to phantom movements likely originates in the central nervous system, since there are no sensory receptors in the phantom. Therefore, this movement-related activity cannot readily be explained by sensory signals resulting from movement. It is possible that this activity is a corollary discharge originating in thalamic motor circuits and encoding the sensory consequences of movement [15], however based on this limited data set, it is impossible to fulfil the rigid experimental criteria provided by Sommer and Wurtz [16]. The same explanation might apply to the movement-related activity recorded in Vim and Vop. However, the role of these nuclei in the planning and execution of movement suggests that their movement-related activity may reflect the dynamics of the planned movement [17].

Anatomic Substrate

From the current data it is not possible to ascertain the origin of the imagery- or phantom movement related activity. This activity could have a cortical origin; imaging studies have demonstrated activation of cortex during phantom movements in patients with remotely acquired amputations [18]. Cortical connections to Vop, the pallidal relay, include afferents from premotor, supplementary motor, and motor cortices [11,19]. Similarly there are reciprocal connections between the sensory nucleus Vc and somatosensory cortex, and the cerebellar relay Vim and primary motor cortex, SMA, and premotor cortex [11,19]. Some authors have hypothesized a thalamic role in monitoring cortical output [20,21,22]. There are also reciprocal connections to several thalamic nuclei from the superior parietal lobule, perhaps correlating with the previously described patients with deficits secondary to parietal lobe injury [ 23,24].

Conclusion

In summary, we have demonstrated activity in thalamic neurons directly related to phantom upper extremity movements in an amputee, and to imagined movements in a set of three intact subjects. The locations and proportions of cells responding to imagined movement were similar to those for cells responding to phantom movement (specifically in Vc), suggesting that the same system subserves both types of movement.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health–National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [Grant numbers NS38493 and NS40059 to FAL, Grant number KNS066099A to WSA].

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Contributor Information

William S. Anderson, Email: wsanderson@partners.org, Instructor in Neurosurgery, Harvard Medical School, Department of Neurosurgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 75 Francis Street CA 138B, Boston, MA USA 02115, (o) +1(617)732-6600, (f) +1(617)713-3050.

Nirit Weiss, Email: nirit.weiss@mountsinai.org, Assistant Professor, Department of Neurosurgery, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Annenberg Building, 8-31, One Gustave L. Levy Place, Box 1136, New York, NY 10029, (o) +1(212)241-6820, (f) +1(212)410-0603.

Herman Christopher Lawson, Email: hclawson@gmail.com, Baltimore Neurosurgery and Spine Center, 5051 Greenspring Avenue, Suite 101, Baltimore, MD 21209, (o) +1(410)664-3680, (f) +1(410)664-3686.

Shinji Ohara, Email: shinji.ohara@gmail.com, Division of Neurosurgery, Neuroscience Center, Fukuoka Sanno Hospital, 3-6-45 Momochihama, Sawara-ku, Fukuoka, Japan 814-0001.

Lance Rowland, Email: lrowland@lifebridgehealth.org, Sinai Hospital of Baltimore, Department of Neurology, 2401 West Belvedere Avenue, Baltimore, MD 21215, (o) +1(410)601-5709.

Frederick A. Lenz, Email: flenz1@jhmi.edu, Professor of Neurosurgery, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Department of Neurosurgery, 600 North Wolfe Street, Meyer 8-181, Baltimore, MD 21287, (o) +1(410)955-2257, (f) +1(443)287-8044.

References

- 1.Decety J, Perani D, Jeannerod M, Bettinardi V, Tadary B, Woods R, Mazziotta JC, Fazio F. Mapping motor representations with positron emission tomography. Nature. 1994;371:600–602. doi: 10.1038/371600a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grafton ST, Arbib MA, Fadiga L, Rizzolatti G. Localization of grasp representations in humans by positron emission tomography. 2. Observation compared with imagination. Experimental Brain Research. 1996;112:103–111. doi: 10.1007/BF00227183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackert BM, Sappok T, Grüsser S, Flor H, Curio G. The eloquence of silent cortex: analysis of afferent input to deafferented cortex in arm amputees. Neuroreport. 2003;14(3):409–412. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200303030-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Draganski B, Moser T, Lummel N, Gänssbauer S, Bogdahn U, Haas F, May A. Decrease of thalamic gray matter following limb amputation. Neuroimage. 2006;31(3):951–957. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ersland L, Rosén G, Lundervold A, Smievoll AI, Tillung T, Sundberg H, Hugdahl K. Phantom limb imaginary fingertapping causes primary motor cortex activation: an fMRI study. Neuroreport. 1996;8(1):207–210. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199612200-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramachandran VS, Brang D, McGeoch PD. Dynamic reorganization of referred sensations by movements of phantom limbs. Neuroreport. 2010;21:727–730. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32833be9ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kühn AA, Doyle L, Pogosyan A, Yarrow K, Kupsch A, Schneider G-H, Hariz MI, Trottenberg T, Brown P. Modulation of beta oscillations in the subthalamic area during motor imagery in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2006;129:695–706. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lenz FA, Garonzik IM, Zirh TA, Dougherty PM. Neuronal activity in the region of the thalamic principal sensory nucleus (ventralis caudalis) in patients with pain following amputations. Neuroscience. 1998;86:1065–1081. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lenz FA, Kwan HC, Dostrovsky JO, Tasker RR, Murphy JT, Lenz YE. Single unit analysis of the human ventral thalamic nuclear group. Activity correlated with movement. Brain. 1990;113 (Pt 6):1795–1821. doi: 10.1093/brain/113.6.1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garonzik IM, Hua SE, Ohara S, Lenz FA. Intraoperative microelectrode and semi-microelectrode recording during the physiological localization of the thalamic nucleus ventral intermediate. Movement Disorders. 2002;17(Suppl 3):S135–S144. doi: 10.1002/mds.10155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamani C, Dostrovsky JO, Lozano AM. The motor thalamus in neurosurgery. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:146–158. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000192166.62017.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis KD, Kiss ZH, Luo L, Tasker RR, Lozano AM, Dostrovsky JO. Phantom sensations generated by thalamic microstimulation. Nature. 1998;391:385–387. doi: 10.1038/34905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giummara MJ, Gibson SJ, Georgiou-Karistianis N, Bradshaw JL. Central mechanisms in phantom limb perception: the past, present and future. Brain Research Reviews. 2007;54:219–232. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diers M, Christmann C, Koeppe C, Ruf M, Flor H. Mirrored, imagined and executed movements differentially activate sensorimotor cortex in amputees with and without phantom limb pain. Pain. 2010;149(2):296–304. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stephan KM, Fink GR, Passingham RE, Silbersweig D, Ceballos-Baumann AO, Frith CD, Frackowiak RS. Functional anatomy of the mental representation of upper extremity movements in healthy subjects. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1995;73:373–386. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.1.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sommer MA, Wurtz RH. Influence of the thalamus on spatial visual processing in frontal cortex. Nature. 2006;444:374–377. doi: 10.1038/nature05279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crammond DJ. Motor imagery: never in your wildest dream. Trends in Neuroscience. 1997;20:54–57. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)30019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flor H, Elbert T, Muhlnickel W, Pantev C, Wienbruch C, Taub E. Cortical reorganization and phantom phenomena in congenital and traumatic upper-extremity amputees. Experimental Brain Research. 1998;119:205–212. doi: 10.1007/s002210050334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lenz FA, Kwan HC, Martin R, Tasker R, Richardson RT, Dostrovsky JO. Characteristics of somatotopic organization and spontaneous neuronal activity in the region of the thalamic principal sensory nucleus in patients with spinal cord transection. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994;72(4):1570–1587. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.4.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guillery RW, Sherman SM. The thalamus as a monitor of motor outputs. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2002;357:1809–1821. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rouiller EM, Tanné J, Moret V, Kermadi I, Boussaoud D, Welker E. Dual morphology and topography of the corticothalamic terminals originating from the primary, supplementary motor, and dorsal premotor cortical areas in macaque monkeys. Journal of Computational Neurology. 1998;396:169–185. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980629)396:2<169::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graziano A, Jones EG. Early withdrawal of axons from higher centers in response to peripheral somatosensory denervation. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(12):3738–3748. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5388-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolpert DM, Goodbody SJ, Husain M. Maintaining internal representations: the role of the superior parietal lobe. Nature Neuroscience. 1998;1:529–533. doi: 10.1038/2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sirigu A, Daprati E, Pradatdiehl P, Franck N, Jeannerod M. Perception of self- generated movement following left parietal lesion. Brain. 1999;122:1867–1874. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.10.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]