Abstract

Purpose

To demonstrate utility, accuracy, and clinical outcomes of electromagnetic tracking and multi-modality image fusion for guidance of biopsy and radiofrequency (RF) ablation procedures.

Materials and Methods

A combination of conventional image guidance (ultrasound/computed tomography (CT)) and a research navigation system were used in 40 patients undergoing biopsy or RF ablation to assist in target localization and needle/electrode placement. The navigation system displays electromagnetically tracked needles and ultrasound images relative to a pre-procedural CT. Additional images (prior positron emission tomography (PET) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)) can be fused with the CT as needed. Needle aiming with and without tracking were compared, the utility of navigation for each procedure was assessed, the system’s off-target tracking error for two different registration methods was evaluated, and setup time recorded.

Results

The tracking error was evaluable in 35 of 40 patients. A basic tracking error of 3.8 ± 2.3 mm was demonstrated using skin fiducials for registration. The error improved to 2.7 ± 1.6 mm when using prior internal needle positions as additional fiducials. Real-time fusion of ultrasound with CT and registration with prior PET and MRI were successful and provided clinically relevant guidance information, enabling 19 of the 40 procedures.

Conclusion

The spatial accuracy of the navigation system is sufficient to display clinically-relevant image guidance information during biopsy and RF ablation. Breath holding and respiratory gating are effective in minimizing the error associated with tissue motion. In 48% of cases, the navigation system provided information critical for successful execution of the procedure. Fusion of real-time ultrasound with CT or prior diagnostic images may enable procedures that are not feasible with standard, single-modality image guidance.

INTRODUCTION

Needle-based interventional procedures such as biopsy and radiofrequency (RF) ablation in the liver, kidneys and other soft-tissue targets are usually guided by ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT) with or without fluoroscopy, or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (1-4). Ultrasound is cost-effective and versatile, may provide real-time visualization of the biopsy needle/RF electrode and target lesion, and can be useful in monitoring RF ablation progression by visualizing the bubble cloud forming during RF ablation. However, US image contrast may be too limited for adequate target visualization, and the 2-dimenional (2D) freehand US images commonly used today for real-time guidance make proper needle/electrode placement challenging when dealing with complex 3D target geometries. CT guidance is typically not real-time, but offers superior 3D visualization of the needle/electrode and target. CT fluoroscopy offers near-real-time 2D or limited 3D imaging but the radiation dose for the medical personnel is of concern. MR guidance may offer superior soft tissue contrast but requires MR compatible equipment and is often not considered cost-effective. Positron Emission Tomography (PET) provides metabolic or functional spatial data, but has largely been ignored for real time interventional feedback due to lack of enabling methods. In practice, real-time ultrasound may be used in conjunction with pre-procedural or intra-procedural CT, but the lack of registration between the two modalities limits the accuracy with which diagnostic information from the pre-procedure CT image can be correlated for guiding needle/electrode placement.

In earlier work (5-10) an electromagnetic (EM) tracking and navigation system was introduced to accurately fuse real-time US with CT, and to provide real-time visualization of tracked interventional needles within pre-procedure CT scans. The system allows registration of pre-procedural CT scans with intra-procedural ultrasound using skin fiducials. Spatial accuracy of better than 6 mm was reported (5). The setup and workflow of the system is described in detail in the Materials and Methods section below. Some systems for real-time image fusion and needle tracking are now commercially available. However, data is only now emerging on the accuracy and efficacy of these systems. In this study we present such data by extending earlier work to a larger patient population. Compared to the retrospective analysis in an earlier study (5), the navigation system in the present study was actively used to guide interventional procedures, accuracy measures were obtained both prospectively and retrospectively, a novel tracking system was employed, and fusion with additional imaging modalities (primarily PET) was demonstrated. Procedures were facilitated that would have otherwise been difficult or impossible to perform without this technology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Population, Hardware and Setup

The clinical trial was approved by the institutional investigational review board, and all patients signed written informed consent. The patient population comprised 28 males and 12 females, mean age 58.0 ± 16.0 years. Patients were selected for this study both who had easy to see lesions and others with difficult to image lesions. The final cohort does not represent a random selection or sampling of our overall patient referral population.

Twenty-two of the procedures were RF ablations, the remaining 18 were needle biopsies. In the patients undergoing RF ablation, a total of 30 lesions were ablated with navigation-assistance and the mean lesion size was 28 mm (median 21, range 12 to 80). In the biopsy patients, 21 lesions were sampled with navigation-assistance, with a mean lesion size of 23 mm (median 17, range 5 to 90). Twenty-five patients were treated in supine position, one prone, and fourteen in decubitus position.

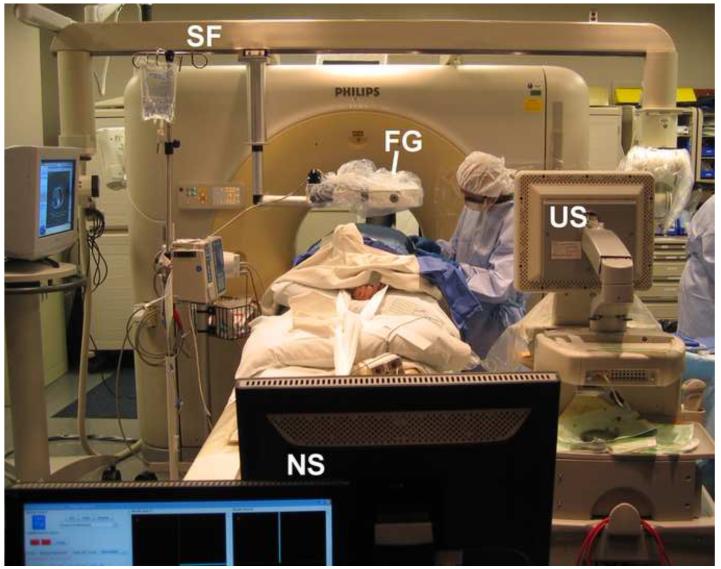

All procedures were carried out on a Brilliance 16-slice CT scanner (Philips Healthcare, Cleveland, OH). For all cases except central lung procedures, a Philips iU22 ultrasound scanner was used for real-time guidance. An Aurora (Northern Digital Inc, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada) electromagnetic tracking system with square field generator (2005 release) was mounted on a three-joint articulated arm (DK Technologies, Barum, Germany), which was attached to the CT gantry via a custom support frame (Figure 1). The ultrasound probe was tracked using a 6-degree of freedom (DoF) EM position tracking sensor (Traxtal Inc, Toronto, Canada) attached to the probe handle. Guider needles (Traxtal Inc) were tracked using a 5-DoF sensor integrated inside the needle tip (5). The guider needles allowed insertion of the biopsy needles and RF ablation electrodes using a coaxial or tandem approach. The 3-prong Cool-tip™ RF ablation cluster electrode (Covidien, Boulder, CO, USA) was used in 14 of the 22 RF ablation procedures. In 6 of these procedures, the cluster electrode was used in combination with the single-electrode Cool-tip™ probe, and in 8 procedures the single-electrode Cool-tip™ electrode was used exclusively.

Figure 1.

Setup for an US/CT guided biopsy procedure with electromagnetic tracking guidance. FG = electromagnetic field generator, US = Ultrasound scanner, NS = Navigation system workstation, SF = support frame

Procedure

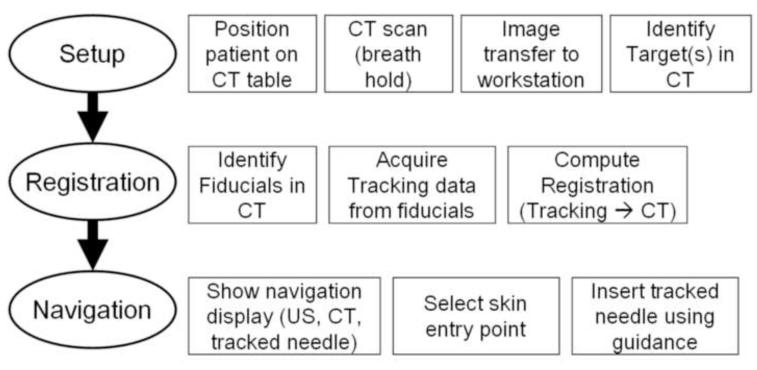

The three-step workflow for the procedures is illustrated in Figure 2. The patients were positioned on a vacuum stabilization mattress on the CT table. All but two of the biopsy procedures were performed under standard conscious sedation, induced by intravenous administration of midazolam and fentanyl. All RF ablation procedures and two of the biopsies were performed under general endotracheal anesthesia with breath holds during CT imaging. Six to seven sterile passive fiducial markers (Beekley Co. Bristol, CT) were placed on the skin near the planned needle entry point (Figure 3). All needle insertions were carried out without use of needle guides attached to the ultrasound probe.

Figure 2.

Procedure workflow using navigation system

Figure 3.

Six or seven fiducials were placed on the patient’s skin to facilitate the registration process.

A pre-procedural CT scan (3 mm slice thickness, 1.5 mm overlap) was obtained at expiration breath-hold in sedated patients, or during interruption of ventilation in the end expiration phase in patients under general anesthesia. Intravenous administration of 50-100 cc of non-ionic contrast was used to visualize the target in 21 of 40 patients. The CT phase with the greatest target conspicuity (arterial or portal venous phase) was transferred to the research navigation system located in the procedure room.

On the navigation system, target locations were identified manually in the CT scan. Targets were most often designated as the center of a tumor, or in some cases as the tumor region with the highest enhancement on CT, perfusion on MR, or standardized uptake value (SUV) on PET. Registration between the tracking system coordinates and CT scan coordinates was obtained by manually identifying the skin fiducials in the CT scan and acquiring the corresponding tracking coordinates by pointing the tracked needle to each of the fiducials during breath-hold. The fiducial registration error (FRE) was computed (11) and displayed and the duration of the registration procedure was recorded.

After registration, the navigation system visualized the tracked needle relative to the CT scan in real-time using two orthogonal multi-planar reconstructions (MPRs) centered at the tracked needle tip. An additional MPR was centered at the currently selected target location and provided feedback about the current distance and pose relative to the target. A fourth viewing panel showed the real-time ultrasound image fused (with variable blending) with the corresponding MPR of the CT scan (see section Multi-modality image fusion, below).

Needle insertions were guided by a combination of conventional real-time ultrasound (except for central lung cases), CT and the navigation system, in addition to MRI (2 cases) and PET (7). During needle placement a CT confirmation scan was obtained whenever clinically indicated, for a total of 1 to 5 confirmation scans per patient. No scans were acquired solely for research purposes.

Setup time for all additional steps necessary to utilize the navigation system was recorded.

Tracking error calculation

In each confirmation scan for which corresponding needle tracking data was available, the tracked needle tip was identified retrospectively. The confirmation scan and needle position were then mapped onto the pre-procedural CT scan (navigation scan) in which the targets had been selected and which was used by the navigation system. The basic tracking error was defined as the distance between the “virtual” needle position computed using the tracking data, and the “gold standard” actual needle position extracted from the confirmation scan (5).

The tracking error was calculated for the entire patient population, and for sub-groups of the population according to target site, procedure type and patient position. Unpaired t-tests were calculated in Matlab R2006a (The Mathworks, Natick, MA) to determine statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) in tracking error between sub-groups.

Two different registration methods were compared retrospectively: (1) Rigid registrations based only on external fiducials, and (2) rigid and affine (i.e. linear but non-rigid, including shearing and scaling) registrations based on the external fiducials and additionally including CT-confirmed internal needle positions in prior confirmation scans as fiducial markers. Note that no additional needle is required for method (2): After recording the needle’s tracking position and confirmation scan, the same needle can be advanced/repositioned as needed. Paired t-tests were used to determine differences (P < 0.05) between the two techniques.

Multi-modality image fusion

Spatial tracking of the ultrasound probe, and registering the tracking coordinate system with the CT coordinate system, enables real-time fusion and visualization of the live ultrasound image with the spatially corresponding MPR from the CT scan as described in prior work (5-7, 9).

In addition, the navigation system can import prior diagnostic 3D image data such as MR or PET. A graphical user interface allows rigid manual registration between the pre-procedural CT and prior diagnostic image. The registered images are displayed jointly with semi-transparent overlays, using different color-maps to distinguish the two images. During the intervention, the tracked needle is visualized relative to the fused images, enabling the intra-procedural use of target location information from prior diagnostic images.

Needle angle selection

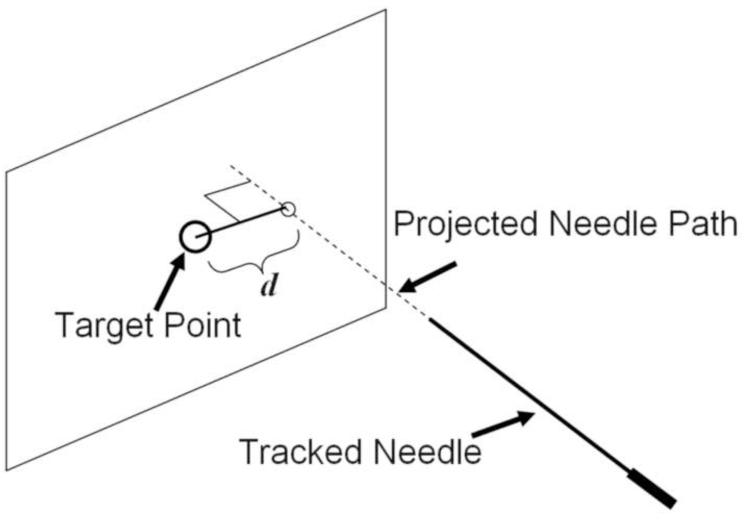

The accuracy of needle targeting with and without the navigation system was evaluated in 15 patients. The comparison was based on the selection of needle angles with both guidance approaches shortly after skin puncture. In two sequential breath holds, the radiologist aimed the needle at the pre-identified target (a) with conventional CT and ultrasound guidance only (blinded to the navigation system), and (b) with the additional feedback from the navigation system. The needle angles, distance to the target, and the relative distance between the two needle positions during aiming were recorded. Based on the two needle angles, the distance d between the target and the projected needle paths was calculated (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Needle aiming accuracy was determined for conventional guidance and for guidance using the navigation system by calculating the distance d between the target point and the projected needle path at the time of aiming.

Assessment of utility

The utility of the navigation technology for each needle/electrode placement was estimated by one interventional radiologist. The utility was labeled “enabling”, “facilitating” or “stand-by”, based on the following criteria: “Enabling” was assigned to placements that would have had a high probability of technical failure or that would have been impossible to perform without the navigation technology, such as biopsy of small lesions that were identified in prior PET studies and that were not visualized with CT or ultrasound. “Facilitating” was assigned to needle/electrode placements in which the navigation may have reduced the time, number of needle sticks or number of CT scans required to position the needle. A procedure was labeled “enabled” and “facilitated”, respectively, when at least one needle placement in the procedure was “enabled” or “facilitated”. “Stand-by” was assigned to the remaining procedures. Imaging and medical records were retrospectively analyzed for surgical pathology, whether diagnosis was made, use of contrast for tracking, number of lesions tracked, size of target lesions. For RF ablation patients, length of follow-up was determined by most recent CT or MR imaging after ablation.

RESULTS

Procedure timing

Total additional setup time for the navigation system was 5.8 +− 2.5 min (mean +- standard deviation). The setup time include time for covering the field generator with a sterile cover (35 +− 14 secs), positioning the field generator (64 +− 66 secs), placing the skin fiducials (52 +− 21), loading the navigation scan into the navigation workstation (54 +− 11 secs), identifying the fiducials in the navigation scan (64 +− 23 secs) and carrying out the registration (81 +− 46secs ).

Some of these steps, e.g. loading the navigation scan and identifying fiducials, were carried out by the system operators concurrently with the ongoing patient preparation by the nurses and physician.

Tracking Error

The tracking error could be evaluated in 35 of the 40 consecutive patients. Five patients were inevaluable because of electronic data loss (2), because the tracking system could not be set up appropriately (1), because the patient was moved during the procedure (1) or because no verification scan was obtained (1). Tracking navigation was still used in the inevaluable patients despite post-procedure data loss. The evaluable patients comprised 26 males and 9 females, mean age 57.9 ± 16.4 years. 3 patients underwent tracked biopsy or RF ablation on two separate occasions. The mean fiducial registration error (FRE) in the evaluable patients was 1.6 ± 0.7 mm. This is a measure of how well the pre-procedural images are fused to the intraprocedural images. A total of 75 verification CT scans with corresponding needle tracking data were obtained in the evaluable patients (2.1 ± 1.4 per patient). The mean basic tracking error determined at these data points was 3.8 ± 2.3 mm. This is the difference between virtual (tracked / displayed) and actual needle positions.

The patient population was divided into groups according to target site (liver versus kidney, the 2 most frequent target sites in this study), procedure type (RF ablation vs. biopsy) and patient position (supine vs. decubitus), and the tracking error was computed for each group individually (Table 1). No statistically significant differences were seen between the tracking errors in different groups (P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviation of the basic tracking error (mm) in various subgroups of the patient population. N indicates the number of data points obtained in each group.

| Target Site: | Liver (N=43): | 4.0 ± 1.9 | Kidney (N=12): | 3.4 ± 2.1 |

| Procedure: | RFA (N=45): | 3.6 ± 1.6 | Biopsie (N=30): | 4.0 ± 3.2 |

| Patient Position: | Supine (N=49): | 3.8 ± 2.4 | Decubitus (N=24): | 3.7 ± 2.3 |

Tracking errors were compared for registrations obtained without and with the use of confirmed internal needle positions as additional fiducials (see section Tracking Error Calculation). One CT-confirmed needle position was used as an additional fiducial for 36 data points; two CT-confirmed needle positions were used as additional fiducials for 12 data points. Table 2 shows the resulting tracking errors (range 2.7 mm to 3.1 mm) for rigid and affine registrations with up to 2 additional internal fiducials. The differences between the tracking errors obtained without and with internal fiducials were statistically significant based on paired t-test analysis (P=0.0062, 0.0156 and 0.0330, respectively, when comparing rigid registration without internal fiducials to rigid with 1 internal, affine with 1 internal, and rigid with 2 internals ), except for the approach with 2 internal fiducials and affine registration (P = 0.1314). On average, the best results were achieved when using affine registrations with 1 additional internal fiducial, which reduced the tracking error by 29% on average compared to the approach with skin fiducials only.

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviation of the tracking error (mm) for registrations obtained with external skin fiducials only and for registrations with up to two CT-confirmed internal needle positions as additional fiducials.

| Registration Type | Number of Internal fiducials |

Tracking Error (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Rigid | 0 | 3.8 ± 2.3 |

| Rigid | 1 | 3.0 ± 1.3 |

| Affine | 1 | 2.7 ± 1.6 |

| Rigid | 2 | 3.1 ± 2.1 |

| Affine | 2 | 2.9 ± 2.5 |

Accuracy of needle angle selection

Needle angle selection with and without the navigation system was evaluated for a total of 19 targets in 15 patients. The targets were located in the liver (N=13), kidney (4), neck (1) and paracardiac mediastinum (1).

The mean distance between target and needle path selected without the navigation system (as defined in Figure 4) was 17.8 ± 17.1 mm (range 3.3 to 81.9, median 14.8). The mean distance between target and path selected with navigation system assistance was 3.3 ± 3.1 mm (range 0.4 to 12.1, median 2.5 mm). The difference was statistically significant (P = 0.0006). The mean angle between the needle paths chosen without and with navigation assistance was 13.3 ± 6.5 degrees (range 6.4 to 35.9).

Clinical experience

Ultrasound and CT guidance were both used in all 40 procedures, although for lung lesions, the ultrasound was only used to define the plane for displaying the CT data. The target lesions had a mean maximum diameter of 25 mm (range 5 to 80 mm). 17 of 18 patients undergoing tracked biopsy and 18 of 20 lesions had biopsies with diagnostic specimens. Two patients undergoing tracked biopsies had a negative pathology results, likely due to sampling error, but one of these had a positive diagnosis from a separate tracked biopsy the same day. 17 of 22 patients had successful RF ablation with targeted lesions completely ablated by standard imaging criteria. 24 of 29 lesions were successfully treated with tracked RF ablation. Mean follow up for successful RF ablation was 11.4 months. Local recurrence was found in 5 out of 29 lesions in 5 out of 22 patients.

Of the 51 navigation-assisted needle placements in the 40 procedures, the utility of navigation was considered “enabling” in 22, “facilitating” in 24, and “stand-by” in 5.

Of the 19 procedures that were enabled by navigation, 10 of 11 enabled biopsies had positive results and 8 of 8 enabled ablations had successful local control, with a mean follow up of 10.5 months. Fused PET guidance was used in 8 biopsies and 3 ablations.

A number of cases will be highlighted in which the navigation system provided targeting information not available using conventional guidance, which may have either enabled successful completion of the procedure or allowed the procedure to be carried out potentially more accurately, faster, with fewer CT scans, or more operator confidence, although these factors were not specifically quantified per patient.

Figure 5 shows navigation displays and confirmation scans during a lung biopsy in a 55 year old male. Needle targeting was initially attempted with (non-fluoro-) CT guidance only. After repositioning the needle and obtaining confirmation CT scans 3 times without use of the navigation system, the needle was still not correctly positioned (Figure 5a). The navigation system was then used to reposition the needle as shown in (Figure 5b). A subsequent CT scans confirmed the correct orientation of the needle for biopsy (Figure 5c).

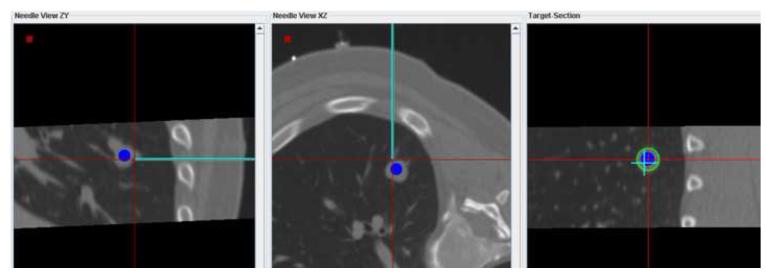

Figure 5.

(a) MPR showing the biopsy needle and target lesion after 3 unsuccessful attempts to position the needle with CT guidance only (no tracking). (b) Navigation system display showing 3 orthogonal MPRs that were used to bring the virtual needle (cyan) into alignment with the target lesion. (c) Confirmation scan after repositioning the needle with the aid of the navigation system shows the needle well positioned for biopsy.

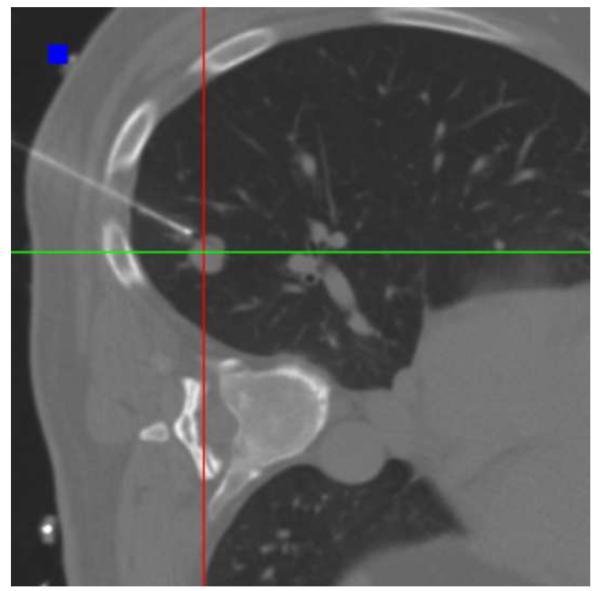

Figure 6 shows navigation displays and confirmation scans obtained during a liver biopsy in a 58 year old male. The lesion was located close to the gall bladder and was poorly visualized without the use of contrast-enhanced CT. With contrast, the lesion was visible only with arterial phase enhancement. Use of the navigation system enabled needle positioning with real-time position feedback relative to the arterial phase enhanced CT obtained at the beginning of the procedure (Figure 6a). A subsequent non-contrast confirmation CT scan did not visualize the target lesion (Figure 6b). However, rigid registration of the confirmation scan with the contrast-enhanced navigation scan in the vicinity of the lesion (Figure 6c) confirmed the correct orientation of the needle.

Figure 6.

(a) Navigation display showing the virtual needle aligned with the target identified in the arterial phase-enhanced CT. (b) Non-contrast enhanced confirmation scan of the needle position does not show the target lesion. (c) After rigid registration of the confirmation scan (pseudo-colored) with the arterial contrast-enhanced scan (gray scale background) in the vicinity of the target lesion, the correct alignment of the needle with the target is confirmed.

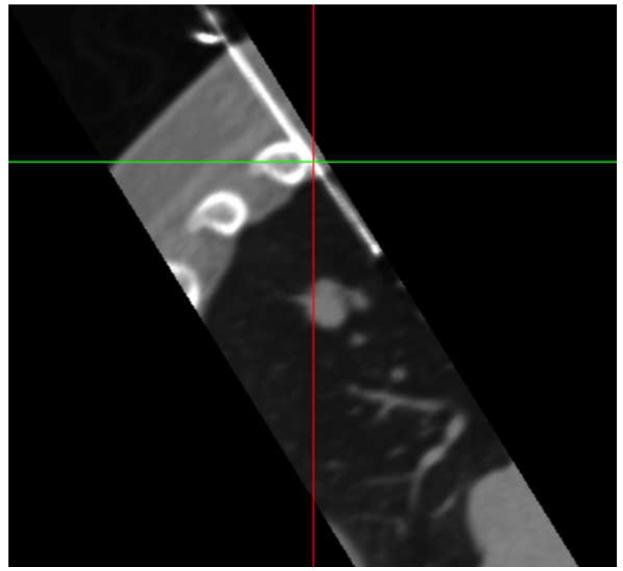

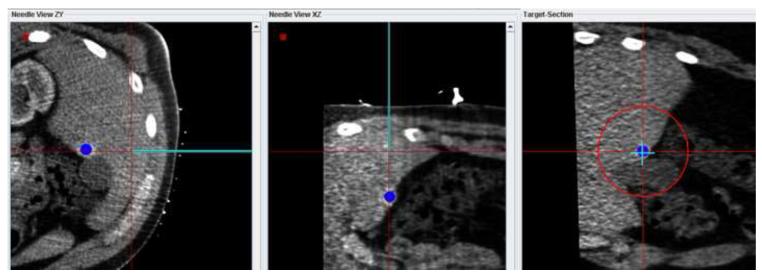

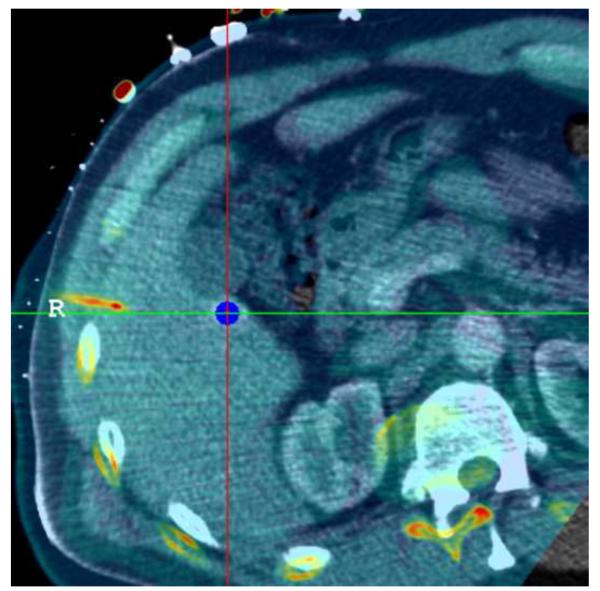

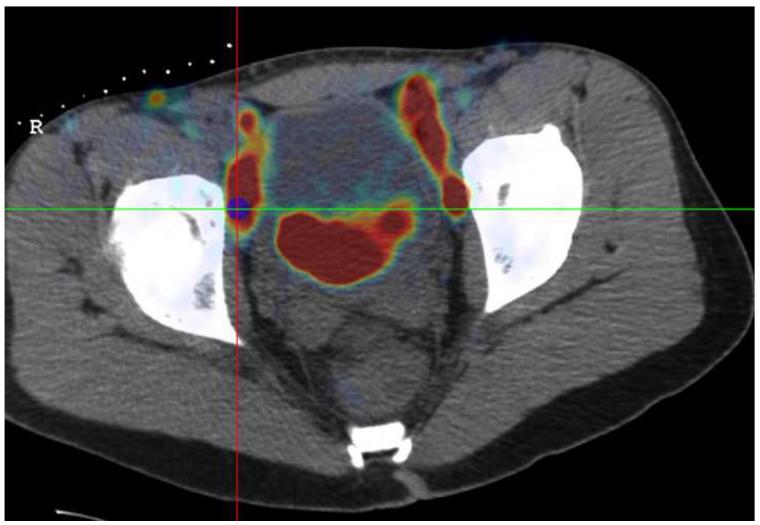

Figure 7 shows screenshots obtained during navigation-assisted right iliac lymph node biopsy in a 21 year old male with recurrent lymphoma. The target was selected after rigid registration of a prior PET scan onto the navigation CT scan (Figure 7a). The navigation system guided needle positioning toward the hot spot in the PET (Figure 7b). A confirmation CT scan showed the accuracy of the navigation display (Figure 7c): The virtual needle displayed by the navigation system is closely aligned with the needle image in the confirmation CT.

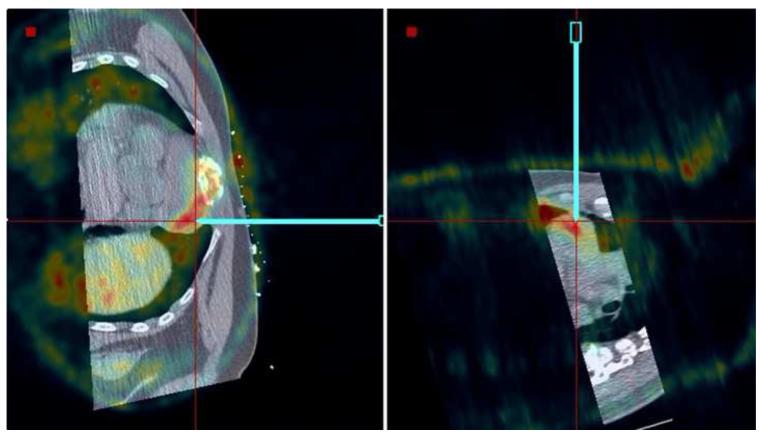

Figure 7.

(a) Target selected based on a prior PET scan registered interactively onto the navigation CT scan. (b) The navigation system was used to guide the needle to the hot spot on PET. (c) A verification CT scan showing the actual needle position (white line) was registered with and superimposed on the navigation scan. The two orthogonal MPRs confirm that the virtual needle (blue line) is correctly registered with the image.

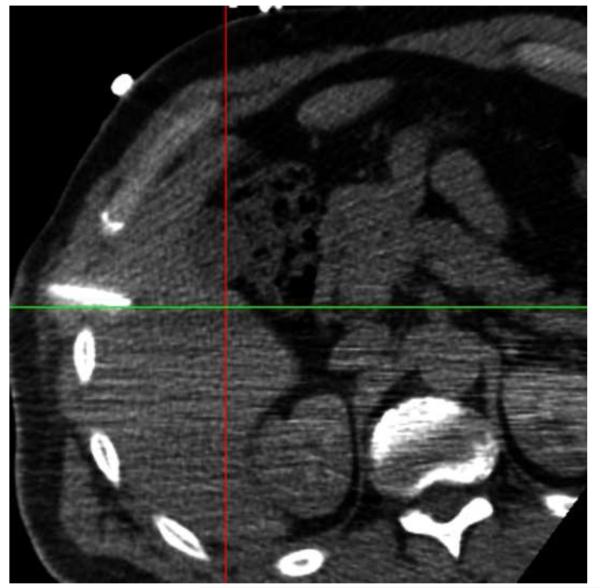

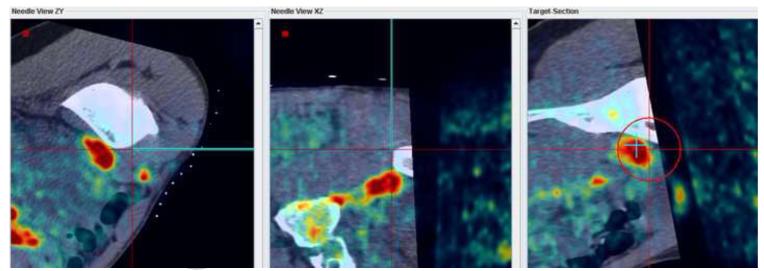

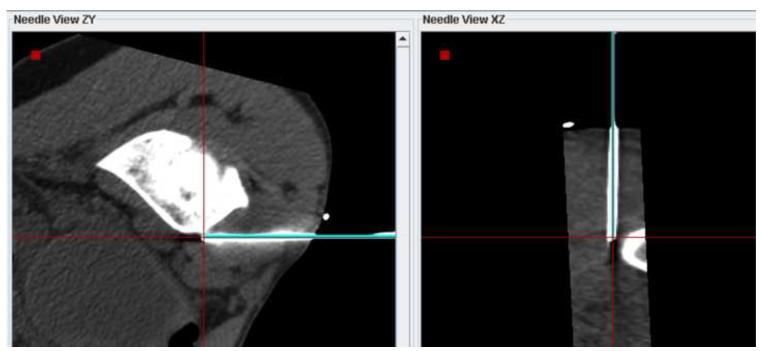

Figure 8 shows needle placement for biopsy of a lymphoma directly adjacent to the heart in a 44 year old male, who underwent an unsuccessful open surgical biopsy and median sternostomy just prior to the percutaneous tracked biopsy. The target was invisible on CT and contrast CT, but showed enhanced activity on a PET/CT scan obtained 6 days earlier. The PET component of the PET/CT scan was imported into the navigation workstation and manually registered with the pre-procedural CT scan, allowing display of the tracked needle relative to both images simultaneously.

Figure 8.

Needle positioning using navigation relative to a prior PET scan registered and fused with the pre-procedural CT. The target location, a lymphoma directly adjacent to the heart, was clearly visible in the PET scan but was occult in CT.

DISCUSSION

A research navigation system for biopsy and ablation procedures was used in conjunction with conventional ultrasound and CT guidance in a 40-patient clinical trial. The navigation system integrated electromagnetic tracking of needles and ultrasound probes with custom software and allowed registration and fusion with prior 3D images to improve target visualization during needle-based procedures.

This study was an extension of prior work in which the safety of an earlier prototype navigation system was demonstrated in a clinical pilot study (5, 6). In that study, the system was not actively used for procedure guidance, and accuracy was evaluated retrospectively only. Compared with the earlier work, improved tracking accuracy was observed in our current study. The basic tracking error improved from 5.8 mm to 3.8 mm, the tracking error based on rigid registration with one prior needle position improved from 4.8 mm to 3.0 mm, and the tracking error based on affine registration with one prior needle position improved from 3.5mm to 2.7 mm. The first two improvements were statistically significant (at P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0006, respectively), while the improvement for the affine registration did not reach significance (P = 0.096).

The improvements in tracking accuracy in the current study compared to the pilot study may be largely attributable to the better performance of the current Aurora electromagnetic tracking system compared to the older system used in the previous study. Laboratory investigations have demonstrated (12, 13) that the newer system has significantly improved accuracy both in an ideal metal-free environment and under more challenging conditions close to bulky medical imaging equipment, as was true in this study.

The accuracy improvement is more pronounced for the basic tracking error based on external fiducials only than for registrations including internal needle positions. This is consistent with the assumption stated in our earlier study that the internally tracked needle provides information about field distortions that can be reduced by including this extra data point in the registration, in particular with affine registrations. Since the field distortions are reduced in the newer Aurora tracking system, so is the potential to partially correct the distortions using tracking data from internal needles.

In addition to the tracking hardware upgrade, it is also possible that more extensive experience with the system and more detailed attention to minimizing respiratory motion artifacts have contributed to reducing the tracking error in the current study.

When combining the patient populations of the pilot study and the current study, the total number of patients is 60, the number of evaluable patients is 54, the basic tracking error is 4.6 +− 2.7 mm, the tracking error based on rigid registration with one prior needle position is 3.5 +− 1.9 mm, and the tracking error based on affine registration with one prior needle position is 2.9 +− 1.7 mm. Similar fusion guided technology has been used for prostate biopsy in 100 patients and is being reported separately. A total of 130 biopsies and 31 ablations in 152 patients have used tracking and fusion technology in our Interventional Radiology section.

Prospective evaluation of needle aiming showed a significantly higher accuracy when using the navigation system compared to conventional guidance. While the task of aiming the needle at a target from a distance does not fully reflect the breadth of the clinical challenge, it does suggest that the navigation system could speed up the procedure by finding the correct needle angle earlier. In settings where accuracy influences outcomes, one can assume that improved accuracy assisted by the navigation system could enable certain procedures and improve clinical outcomes, especially in challenging cases and ablations, where composite treatments are dependent upon the collective accuracy of component needle positions.

Prospective use of the navigation system allowed needle/electrode placement with higher confidence in all cases, and provided valuable target information not available by conventional image guidance in the majority of cases. 22 needle/electrode placements in 19 procedures were enabled by the tracking technology and would have had a high risk of technical failure with conventional image guidance only, due to lack of target localization. These were primarily cases in which the target lesion was only visible in an arterial phase CT, or on prior PET or PET/CT scan, which were then brought into the procedure by image registration with the navigation CT. The technology was especially enabling for targets that were only visible during brief arterial phase enhancement in contrast enhanced CT.

Furthermore, the additional information allowed completion of at least two lung biopsies in less time than they would have taken with conventional guidance, based on the number of failed needle positioning attempts with CT guidance only. Whether the addition of navigation added accuracy or integrity to these procedures remains speculative, since no randomization was performed. However, the use of navigation allowed the physician to proceed with procedures where targets could not be identified with conventional methods, and procedures may not have been performed at all without navigation in many cases. It is unknown whether standard guidance methods and an experienced operator could have guessed target locations using mental estimates.

As with any new technology, there is a learning curve before the system can be used efficiently. Since a number of the setup tasks can be performed concurrently, however, the impact on the workflow is small. Some of the steps involved in the setup (such as the attachment and identification of fiducials) may be easily accelerated in the future with improved hardware design and image analysis software. This has actually already been prototyped and commercially released.

It is important to note the limitations of this study. The number of patients was relatively small, and the patient population was diverse in diagnosis, target site, and ventilation method. Therefore, a statistically meaningful comparison of outcomes with a control group was not possible. Also, all procedures were carried out and analyzed by two radiologists under the direct guidance of a single operator at one institution. A randomized multi-center trial has been designed and would better evaluate the potential benefits of the navigation system presented in this study. Furthermore, there certainly is patient selection bias based upon the fact that some patients with difficult to see lesions were more likely to be enrolled in this trial. We can likely extrapolate to say that in the setting of patients with difficult to see lesions, the addition of the technology enhanced the physician’s sense of accurate guidance and confidence in target localization.

In conclusion, electromagnetic tracking of needles and ultrasound probes with integrated miniaturized sensors enables multimodality interventional navigation on pre-procedural CT, MR, and PET and real-time fusion of CT with ultrasound. This technology may improve operator confidence and potentially increase accuracy of needle/electrode placement in cases where ultrasound visualization of the target is poor or not available. Fusion guidance significantly improved angle selections over conventional methods. The addition of needle and ultrasound tracking improved needle path off-target error from 17.8 ± 17.1 mm to 3.3 ± 3.1 mm, and changed the insertion angle by 13.3 ± 6.5 degrees. Such major improvements over conventional methods quantify the value of this technology to the interventional physician, especially for procedures where improved accuracy could translate to improved outcomes. Registration and use of pre-procedural diagnostic or metabolic images enabled identification and localization of targets and directly impacted outcomes in biopsy and ablation interventions.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH Clinical Center and by a Collaborative Research and Development Agreement between NIH and Philips Healthcare.

Footnotes

Disclosures: BJW and Philips have intellectual property in the field. JK, SX, and NG are salaried employees of Philips Electronics.

Clinical Trial Information: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00102544 A full description of this trial can be found at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct/show/NCT00102544?order=1

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Goldberg SN, Dupuy DE. Image-guided radiofrequency tumor ablation: challenges and opportunities--part I. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:1021–1032. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61587-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldberg SN. Radiofrequency tumor ablation: principles and techniques. Eur J Ultrasound. 2001;13:129–147. doi: 10.1016/s0929-8266(01)00126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dupuy DE, Goldberg SN. Image-guided radiofrequency tumor ablation: challenges and opportunities--part II. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:1135–1148. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61670-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boss A, Clasen S, Kuczyk M, et al. Magnetic resonance-guided percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of renal cell carcinomas: a pilot clinical study. Invest Radiol. 2005;40:583–590. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000174473.32130.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krücker J, Xu S, Glossop N, et al. Electromagnetic tracking for thermal ablation and biopsy guidance: clinical evaluation of spatial accuracy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;18:1141–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krücker J, Xu S, Viswanathan A, Shen E, Glossop N, Wood BJ. Clinical evaluation of electromagnetic tracking for biopsy and radiofrequency ablation guidance. Proceedings of CARS 2006, Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2006;1:169–171. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kruecker J, Viswanathan A, Borgert J, Glossop N, Yang Y, Wood BJ. An electromagnetically tracked laparoscopic ultrasound for multi-modality minimally invasive surgery. Proceedings of CARS 2005, International Congress Series 1281.2005. pp. 746–751. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kruecker J, Viswanathan A, Glossop N, Xu S, Yang Y, Wood BJ. Electromagnetic Tracking for Biopsy and Radiofrequency Ablation. Proceedings of SIR.2006. p. S84. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kruecker J, Xu S, Glossop N, Neeman Z, Locklin J, Wood BJ. Electromagnetic needle tracking and multi-modality imaging for biopsy and ablation guidance. Proceedings of CARS 2007, Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2007;2:S147–150. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu S, Kruecker J, Viswanathan A, Wood BJ. Automatic localization of fiducial markers for Transrectal Ultrasound (TRUS) guided needle biopsy—phantom study. Proceedings of CARS 2006, Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2006;1:512–513. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitzpatrick JM, West JB, Maurer CR., Jr. Predicting error in rigid-body point-based registration. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1998;17:694–702. doi: 10.1109/42.736021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen E, Shechter G, Kruecker J, Stanton D. Quantification of AC electromagnetic tracking system accuracy in a CT scanner environment. Proceedings of SPIE Medical Imaging. 2007;6509:65090L1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hummel JB, Bax MR, Figl ML, et al. Design and application of an assessment protocol for electromagnetic tracking systems. Med Phys. 2005;32:2371–2379. doi: 10.1118/1.1944327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]