Summary

Background

In hypercholesterolemia, platelets demonstrate increased reactivity and promote the development of cardiovascular disease.

Objective

This study was carried out to investigate the contribution of the ADP receptor P2Y12-mediated pathway in platelet hyperreactivity due to hypercholesterolemia.

Methods

Low-density lipoprotein receptor deficient mice and C57Bl/6 wild type mice were fed on normal chow and high-fat (Western or Paigen) diets for 8 weeks to generate differently elevated cholesterol levels. P2Y12 receptor induced functional responses via Gi signaling were studied ex vivo when washed murine platelets were activated by 2MeSADP and PAR4 agonist AYPGKF in the presence and absence of indomethacin. Platelet aggregation, secretion, αIIbβ3 receptor activation and the phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) and Akt were analyzed.

Results

Plasma cholesterol levels ranged from 69±10 to 1011±185 mg/dl depending on diet in mice with different genotypes. Agonist-dependent aggregation, dense and α-granule secretion and JON/A binding were gradually and significantly (P < 0.05) augmented at low agonist concentration in correlation with the increasing plasma cholesterol levels even if elevated thromboxane generation was blocked. These functional responses were induced via increased level of Gi mediated ERK and Akt phosphorylation in hypercholesterolemic mice versus normocholesterolemic animals. In addition, blocking of the P2Y12 receptor by AR-C69931MX (Cangrelor) resulted in strongly reduced platelet aggregation in mice with elevated cholesterol levels compared to normocholesterolemic controls.

Conclusions

These data revealed that the P2Y12 receptor pathway was substantially involved in platelet hyperreactivity associated with mild and severe hypercholesterolemia.

Keywords: platelet signaling, LDLR, hypercholesterolemia, P2Y12 receptor

Introduction

Hypercholesterolemia related increased platelet sensitivity to agonists was first studied in vitro a long time ago [1–3] and since then platelet hyperreactivity has been considered as one of the major contributors to the development of atherosclerosis and thrombotic complications in several diseases [4–6]. In familial hypercholesterolemia, homozygous subjects with extremely high cholesterol levels showed even larger risk for arterial thrombosis than normocholesterolemic individuals [7]. Enhanced platelet reactivity was previously described as the consequence of altered cholesterol composition of platelet membrane accompanied with increased thromboxane A2 (TXA2) generation due to the excess cholesterol [1,2,5,7]. In turn, a few data were available about the positive effect of the reduction of high cholesterol membrane levels on platelet function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) by using reconstituted HDL [8] or plasma cholesterol lowering diets in animal models [9,10]. Some recent publications demonstrated newly explored mechanisms of platelet activation by native and oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL) via ApoE-R2’ and CD36 receptors, respectively, upon p38MAPK phosphorylation [11–13]. However, other ‘classical’ signaling pathways, which may also contribute to platelet hyperactivity in the presence of elevated plasma cholesterol levels, have not been clarified in detail.

Platelet lipid rafts serve as a platform for selective receptor-mediated pathways. In earlier work we described signaling through the ADP receptor P2Y12 mediated by Gi that showed a requirement for lipid rafts, since cholesterol-depleted platelets displayed a significant reduction in ADP-induced aggregation, but not in the extent of shape change or intracellular calcium release mediated via Gq [14]. In addition, the active metabolite of the P2Y12 antagonist clopidogrel interfered with this ADP receptor assembly and its localization in lipid rafts [15]. It is well known that P2Y12 receptor-mediated signaling processes are essential for the stabilization of platelet aggregates as reviewed in Ref [16]. Antagonism of this receptor provided a therapeutic benefit in reducing major cardiovascular events and platelet procoagulant activity in vascular and metabolic diseases with dyslipidemia [17–19]. Overall, we hypothesize that downstream signaling through the P2Y12 receptor may be a major contributor to the generation of enhanced platelet reactivity due to hypercholesterolemia.

In order to study the involvement of the P2Y12 receptor in platelet hyperactivity in mild and severe hypercholesterolemic conditions, low-density lipoprotein receptor deficient mice (LDLR−/−) and C57Bl/6 wild type (WT) mice were fed on normal chow and two types of high-fat (Western and Paigen) diets for 8 weeks to generate differently elevated plasma cholesterol levels. LDLR−/− mice were previously used to examine platelet function and in vivo thrombus formation in hypercholesterolemia [20,21]. In this ex vivo study, washed murine platelets were activated by 2MeSADP and the PAR4 agonist AYPGKF at low and high concentrations and platelet aggregation, ATP secretion, P-selectin expression and JON/A binding to activated murine αIIbβ3 receptors were observed. In addition, P2Y12 receptor coupled Gi signaling was also evaluated by detecting the phosphorylation level of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) and Akt [22,23]. Although thrombin receptor PAR1- and PAR4-coupled Gq and G13 are not present in lipid rafts [24], PAR4 mediated signaling was also investigated because PARs indirectly activate Gi via secreted ADP [25]. Our aim was to analyze whether hypercholesterolemic animals having individually increased plasma cholesterol levels showed elevated platelet reactivity downstream of P2Y12 receptor compared to healthy mice. We also defined the relative contribution of TXA2 generation to these events.

Materials and methods

Mice

LDLR−/− and C57Bl/6 WT mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and bred in the Central Animal Facility of Jefferson University Medical School, Philadelphia, PA. There was no significant difference in the gender of the mice in either subgroup (in average 60% males and 40% females). At the age of week 4, mice were fed on standard (low-fat) chow diet [4.5% saturated fat, 0.02% cholesterol], or Western diet [21.2% saturated fat, 0.2% cholesterol, cholate-free; TD88137] (Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI), or Paigen diet [7.5% cocoa butter, 15.8% saturated fat, 1.25% cholesterol, 0.5% sodium cholate; TD88051] (Harlan Teklad) for 8 weeks. Total plasma cholesterol levels were followed-up at three different time points (weeks 6, 8 and 12 of age). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Temple University, Philadelphia, PA.

Materials

2MeSADP, apyrase (grade VII), human fibrinogen (type I), bovine serum albumin (BSA, fraction V), paraformaldehyde (PFA) and indomethacin were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Hexapeptide AYPGKF was custom-synthesized at Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). AR-C69931MX (cangrelor) was a gift from Astra Zeneca. Anti-phospho(Ser473)-Akt, anti-phospho(Thr202/Tyr204)-ERK, anti-Akt and anti-ERK antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody was from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA). Millipore Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP substrate and polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane were used for all immunoblotting. Luciferin-luciferase reagent was purchased from Chrono-Log (Havertown, PA). The anti-JON/A-PE and anti-CD62-FITC antibodies were obtained from Emfret Analytics (Wuerzburg, Germany). All other reagents were of reagent grade and deionized water was used throughout.

Isolation of murine platelets

Studies using mice were performed under protocols that were approved by the Animal Use and Care Committees of Temple University and Thomas Jefferson University. Blood was collected from the vena cava of anesthetized mice into syringes containing 1/10th blood volume of 3.8% sodium citrate as anticoagulant. Red blood cells were removed by centrifugation at 100 g for 10 min. PRP was removed and platelets were pelleted at 400 g for 10 min. The platelet pellet was resuspended in Tyrode’s buffer (138 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 3 mM NaH2PO4, 5 mM glucose, 10 mM HEPES, and 0.2% BSA; pH 7.4) containing 0.1 U/ml apyrase. In order to obtain appropriate volume of platelet samples for each experiment, washed platelets from at least different 3 mice with the same background were pooled. Cells were counted and concentration of cells was adjusted to 2×108 platelets/ml.

Platelet aggregation and dense granule secretion

Aggregation of 250 μl of washed murine platelets was analyzed by using a lumiaggregometer (Chrono-Log). Aggregation was measured using light transmission under stirring conditions(900 rpm) at 37°C. Agonists were added forplatelet stimulation. Each sample was allowed to aggregate for at least 3.5 min. Subsequently, platelet secretion was determined by measuring ATP secretion using the Lumi-chrome reagent during the aggregation and the corresponding luminescence was measured.

Western blot analysis

Platelet samples were prepared during aggregation, and were immediately boiled for 10 min. Proteins were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gel and then transferred onto PVDF membranes. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked by incubation in Tris–buffered saline/Tween (TBST; 20 mM Tris, 140 mM NaCl, 0.1 % (vol/vol) Tween 20) containing 5% (wt/vol) BSA for 60 min at RT, followed by incubation overnight at 4°C with gentle agitation with primary antibody (in TBST with 5 % BSA). After three washes for 5 min each with TBST, the membranes were probed with the HRP-labeled secondary antibody (1:10 000 dilution in TBST with 5% BSA) for 1 hour at RT. After additional washing steps, membranes were then incubated with chemiluminescent HRP substrate for 5 min at RT, and immunoreactivity was detected using Fuji Film Luminescent Image Analyzer (model LAS-3000 CH, Tokyo, Japan). Densitometric analyses were performed by using Fuji Film Science Lab, Image Gauge, Version 4.22. The level of ERK and Akt phosphorylation was determined by calculation of the ratio of each phosphorylation level to its own total value and expressed as fold increase over control.

Measurement of TXB2 generation

Isolated murine platelets (250 μl) were stimulated by agonists in an aggregometer. The stimulation was performed for 3.5 min and the reaction stopped by quickly freezing the sample in a dry ice-methanol bath. Prior to performing the TXB2 measurement, samples were thawed at RT and centrifuged at 15000 g for 3 min at RT to remove lyzed platelets. The supernatant were diluted 1:50 with the standard diluent (assay buffer). Levels of TXB2 were determined in duplicate according to the manufacturer’s instructions using a Correlate-EIA Thromboxane B2 Enzyme Immonoassay kit (Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI).

Flow cytometry

All determinations were performed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Washed murine platelets were analyzed to measure the level of surface expression of P-selectin receptors by using anti-CD62-FITC antibody, and the level of activated αIIbβ3 receptors by JON/A-PE antibody. Aliquots (0.1 ml) of suspensions of washed murine platelets (2×106/ml) in Tyrode’s buffer (pH 7.4) were stimulated with 2MeSADP or AYPGKF and incubated simultaneously with saturating concentrations of antibodies for 15 min at 37°C in the dark. To fix the platelets, 1% PFA dissolved in PBS was added into samples. 10,000 platelet events were acquired per sample and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of positive platelets was analyzed.

Statistical analyses

Data were statistically analyzed by 2-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Reported values are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Results

Mice on normal and high-fat diets demonstrated differently elevated plasma cholesterol levels

LDLR−/− and WT mice were fed on chow and high-fat diets for 8 weeks to elevate their cholesterol levels. Feeding of mice with either the Western or Paigen diet was earlier used for up to 6 months to induce severe dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis in animal models [26,27]. In the present study, WT mice on the Western and Paigen diets had 2-and 2.5-fold increases in total plasma cholesterol (125±17 mg/dl and 185±15 mg/dl, respectively), whilst LDLR−/− mice fed on a standard chow diet showed 3-fold (191±23 mg/dl) increased cholesterol levels compared to WT animals on the standard chow diet (69±10 mg/dl). On the other hand, LDLR−/− mice fed on the Western diet had extremely high cholesterol levels (1011±185 mg/dl) (Table 1). No marked difference in cholesterol levels was seen between males and females (data not shown). Thus, we were able to evaluate the effect of hypercholesterolemic conditions on platelets and investigate the involvement of the P2Y12 receptor-mediated pathway in platelet hyperreactivity due to mild and severe hypercholesterolemia.

Table 1.

Total plasma cholesterol levels in WT and LDLR−/− mice fed on standard chow, Western or Paigen diets.

| Genotype (diet) | LDLR+/+ (Chow) | LDLR+/+ (West) | LDLR+/+ (Paigen) | LDLR−/− (Chow) | LDLR−/− (West) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 69 ± 10 | 125 ± 17* | 185 ± 15* | 191 ± 23* | 1011 ± 185** |

* P < 0.05 ** P < 0.01 |

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM.

P < 0.05 or

P < 0.01 represent significant differences from normocholesterolemic control (WT on chow). Results were analyzed by using Student’s t test.

Increased platelet aggregation occurred in hypercholesterolemia via the P2Y12 receptor pathway

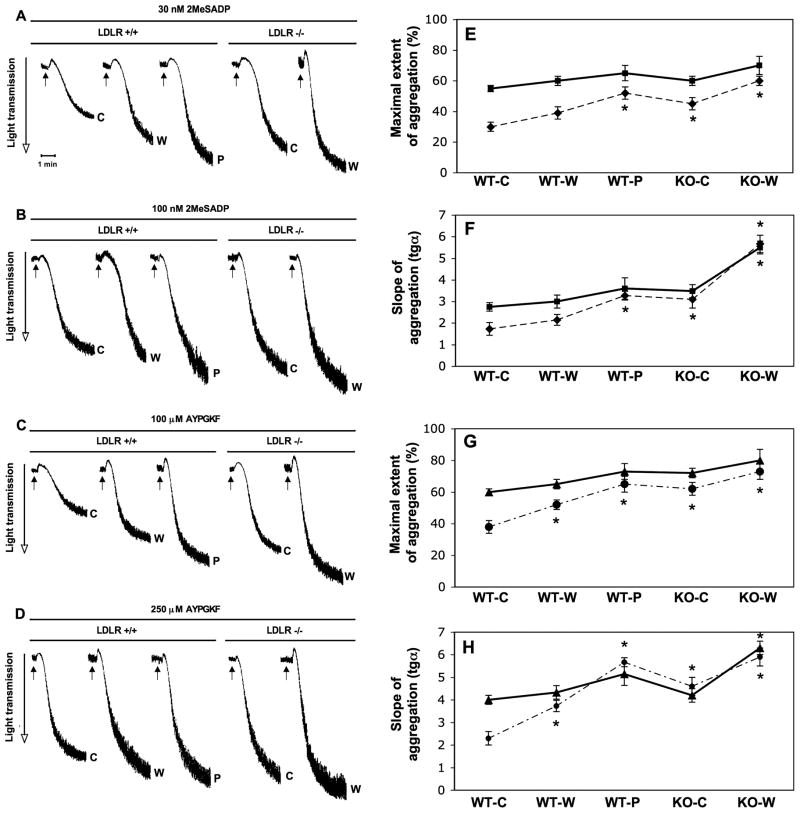

Our group formerly investigated ADP receptor- and PARs-induced platelet aggregation, secretion and αIIbβ3 receptor activation in normal human platelets and analyzed in detail signaling pathways such as that involving Gi [22,23,25,28,29]. Here we tested the contribution of the P2Y12 receptor pathway in the development of enhanced reactivity of platelets in hypercholesterolemia upon stimulation with low and sub-maximal concentrations of the ADP receptor agonist 2MeSADP and PAR4 activating AYPGKF peptide. We found that 2MeSADP and AYPGKF-induced aggregation (Fig. 1A and C) was gradually and significantly (P < 0.05) increased to a greater maximal extent (Fig. 1E and G) in mice with ≥ 2.5-fold increase in cholesterol level versus normocholesterolemic controls when low agonist concentration was used. A similar tendency was seen in the degree of aggregation curve slopes (Fig. 1F and H). However, there was no substantial difference in extent of aggregation using sub-maximal concentration of agonists (Fig. 1B and D). In the case of LDLR−/− animals fed on the Western diet, further increase was found in the slope of aggregation even at the highest agonist concentration (Fig. 1F and H). In summary, we showed a positive and significant correlation between platelet aggregation as a response to P2Y12 receptor agonists and the effect of increased levels of plasma cholesterol on platelets in these mice. Our findings were consistent with previous observations in which LDLR−/− mice on a high-fat diet formed significantly larger thrombi with increased platelet accumulation in vivo after vascular injury compared to normocholesterolemic WT mice [26].

Fig. 1.

2MeSADP and AYPGKF-induced platelet aggregation in WT and LDLR−/− mice on chow (c), Western (w) and Paigen (p) diets in response to a low and a sub-maximal concentration of agonists. Isolated murine platelets were activated by 30 nM and 100 nM 2MeSADP (A & B) and 100 and 250 μM AYPGKF (C & D) for 3.5 min at 37°C in stirring condition without indomethacin pre-treatment. The tracings are representative of results from 3 independent experiments. The maximal extent (E & G) and the slope (F & H) of aggregation tracings were quantified and depicted in graph. ‘Filled’ line represents data from aggregation by sub-maximal agonist concentration, while ‘slash’ line means at low concentration of agonist (2MeSADP: E & F; AYPGKF: G & H). *P < 0.05 versus normocholesterolemic mice by using Student’s t test. Mean ± SEM.

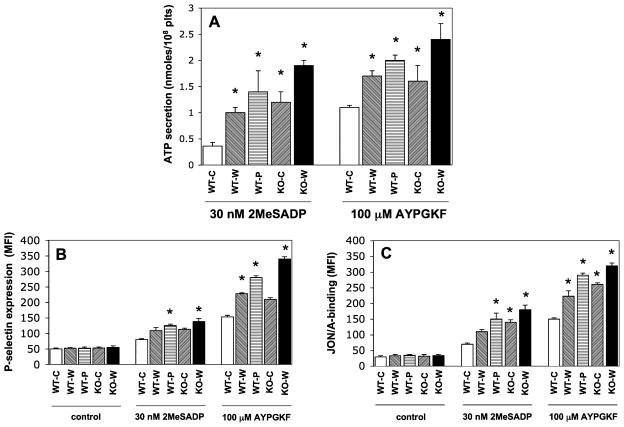

Enhanced levels of dense and α-granule secretion, along with αIIbβ3 receptor activation, were measured in mice with abnormal cholesterol levels

As shown in Fig. 2A, the level of ATP secretion from dense granules was significantly (P < 0.05) elevated in all hypercholesterolemic mice compared to healthy WT mice. These data were consistent with the aggregation findings suggesting that increased dense-granule release augmented platelet reactivity via Gi signaling [25]. Furthermore, agonist- induced P-selectin exposure was significantly (P < 0.05) elevated in platelets from mice on high-fat diets versus healthy animals. However, the increment in P-selectin positivity was less substantial (p=0.064) in WT mice on Western diet versus controls at 2MeSADP stimulation compared to that seen in the AYPGKF-activated platelets. Furthermore, there was only a marked but statistically not significant (p=0.057) increase in P-selectin expression between LDLR−/− mice and WT mice on chow diet. Unstimulated samples from each group showed no difference in the baseline parameters (Fig. 2B). In addition, platelet reactivity in these mice was accompanied by gradually and significantly (P < 0.05) elevated level of JON/A-positive platelets (Fig. 2C), which positively correlated with the aggregation tracings. When platelets were stimulated with a sub-maximal agonist concentration, no significant difference was observed in terms of the functional responses of these platelets (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the levels of dense and α-granule secretion as well as αIIbβ3 receptor activation downstream of P2Y12receptor pathway in mice on chow (c), Western (w) and Paigen (p) diets. (A) Simultaneous dense granule secretion was measured during aggregation and expressed as ATP secretion (nmol/108 platelets). (B) Isolated platelets from LDLR−/− and WT mice were stimulated with 2MeSADP (30 nM) and PAR4 agonist AYPGKF (100 μM) for 15 min at 37°C in non-stirring condition in the presence of FITC-labeled anti-mouse-P-selectin (CD62) antibody to detect α-granule release. Reactions were terminated by fixing platelets with (1%) PFA and then analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) We also tested the JON/A binding to measure the level of activatedαIIbβ3 receptors in the same samples. *P < 0.05 versus normocholesterolemic mice by using Student’s t test. The bars represent the results of 3 independent experiments. Mean ± SEM.

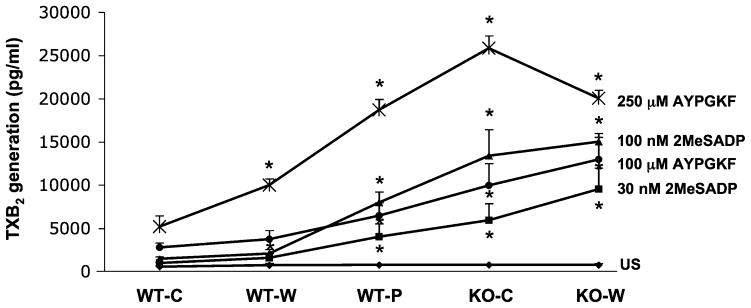

Platelet hyperreactivity was accompanied by elevated levels of thromboxane generation in hypercholesterolemic mice

According to previous reports [5,7] a significantly increased level of TXB2 was measured in humans due to enhanced TXA2 synthesis at higher levels of availability of arachidonate. This lipid mediator was shown to trigger Gq mediated responses via a second wave of platelet secretion resulting in a positive feedback in normal platelets [30]. Here we also determined the level of TXA2 synthesis upon platelet stimulation via ADP- receptors and PARs in different dyslipidemic states and compared to normocholesterolemic mice (Fig. 3). There was no significant difference in the baseline TXB2 values among unstimulated samples. Platelets from samples with increasingly elevated cholesterol levels demonstrated significantly (P < 0.05) larger TXB2 production regardless of whether they were stimulated with either low or sub-maximal agonist concentration (Fig. 3). There was one exception: at 250 μM AYPGKF stimulation, when LDLR−/− mice on Western diet did not show even higher TXB2 levels compared to LDLR −/− mice on the chow diet.

Fig. 3.

The level of TxB2 generation in WT and LDLR−/− mice on chow (c), Western (w) and Paigen (p) diets in response to a low and a sub-maximal concentration of P2Y12 receptor agonists. Isolated murine platelets were stimulated by 2MeSADP and AYPGKF in an aggregometer. The stimulation was performed for 3.5 min and the reaction was stopped by quickly freezing the sample in a dry ice-methanol bath. Samples were processed in ELISA kit to measure the level of TXB2. *P < 0.05 versus normocholesterolemic mice by using Student’s t test. The data represent mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments.

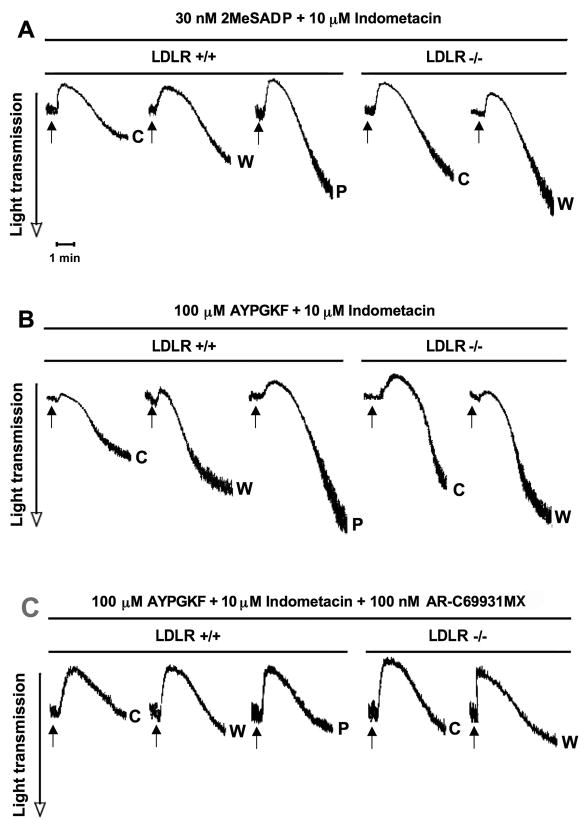

Relative contribution of thromboxane generation and the P2Y12 receptor pathway to enhanced platelet reactivity in hypercholesterolemia

We next studied the involvement of P2Y12 receptor signaling in platelet activation in the absence of increased TXA2 generation when murine platelets were pretreated with indomethacin in order to prevent the effect of TXA2 production on signaling events. A similar tendency was observed in aggregation at low concentration of 2MeSADP and AYPGKF as seen in the presence of TXA2 (Fig. 4A and B). On the other hand, as expected, the level of maximal extent and slope of aggregation curves was markedly decreased in the absence of TXA2 compared to untreated samples above (Fig. 4C–F). To examine the role of the activation pathway downstream of P2Y12 receptor, the specific antagonist AR-C69931MX was used in indomethacin-pretreated platelet samples prior to aggregation. Hypercholesterolemic platelets showed strongly reduced platelet aggregation in mice with higher than normal cholesterol levels compared to healthy controls in response to a low concentration of AYPGKF when neither TXA2 synthesis nor P2Y12 receptor-induced signaling occurred (Fig. 4G). Overall, under these conditions, no significant difference in aggregation was observed between mice with normal and mildly or severely elevated cholesterol levels. These data confirmed that the increased level of TXA2 synthesis largely but not exclusively contributed to platelet hyperreactivity in hypercholesterolemia and the P2Y12 receptor-induced pathway was functionally active in its regulation.

Fig. 4.

2MeSADP and AYPGKF-induced aggregation of platelets after preincubation with indomethacin in WT and LDLR−/− mice on chow (c), Western (w) and Paigen (p) diets. Isolated murine platelets were pre-treated with 10 μM indomethacin for 10 min and activated by 30 nM 2MeSADP (A) and 100 μM AYPGKF (B) for 3.5 min at 37°C in stirring condition. The maximal extent (C & E) and the slope (D & F) of aggregation tracings were quantified and depicted in graph. ‘Slash’ line depicts values in the presence of TXA2 production, and ‘filled’ line represents data when TXA2 generation was blocked (2MeSADP: C & D; AYPGKF: E & F). *P < 0.05 versus normocholesterolemic mice by using Student’s t test. (G) Washed murine platelets were also stimulated in response to 100 μM AYPGKF in the presence of 10 μM indomethacin for 10 min and 100 nM AR-C69931MX added prior to platelet aggregation. The tracings are representative of results from 3 independent experiments. Mean ± SEM.

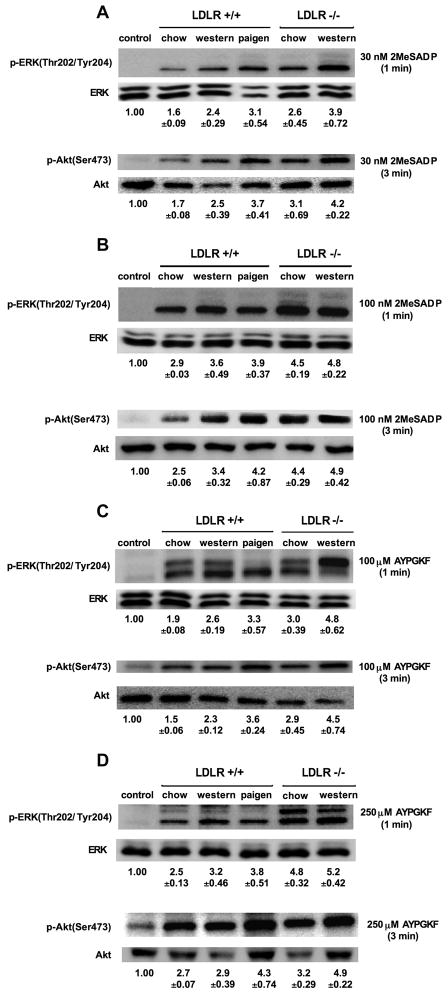

Increased platelet responses were mediated by enhanced ERK and Akt phosphorylation via the Gi pathway in mice with hypercholesterolemia

ADP activates ERK downstream of P2Y receptors in a Src-family-kinase-dependent manner, which requires signaling from both P2Y1 and P2Y12 receptors, but does not depend on outside-in signaling [29]. We here determined whether the P2Y12 receptor pathway induced higher level of ERK phosphorylation in mice with increased levels of cholesterol. In response to low concentrations of 2MeSADP (Fig. 5A and B) and AYPGKF (Fig. 5C and D) a gradual and significant (P < 0.05) increase in ERK phosphorylation was detected in platelets from hypercholesterolemic mice compared to normocholesterolemic mice. However, in response to sub-maximal concentration of agonists, this tendency in ERK phosphorylation was less evident among platelet samples from the WT mice on different diets and LDLR−/− mice that demonstrated only a moderately higher level of ERK phosphorylation.

Fig. 5.

ERK and Akt phosphorylation in response to 2MeSADP and AYPGKF in normo-and hypercholesterolemic mice. WT and LDLR−/− mice with differently high cholesterol levels were pre-treated with 10 μM indomethacin for 10 min and then stimulated with 30 nM and 100 nM 2MeSADP (A & B) as well as 100 μM and 250 μM AYPGKF (C & D) at 37°C in stirring condition for 1 min for activating ERK, and for 3 min in order to induce Akt phosphorylation. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 3x SDS sample buffer. The phosphorylation level of proteins was analyzed by Western blot analysis with anti-phospho(Thr202/Tyr204)-ERK and anti-phospho(Ser473)-Akt antibodies. The total amount of proteins was measured with anti-ERK and anti-Akt antibodies as lane loading. Phosphorylation data were quantified by densitometry and analyzed in fold increase over control (mean ± SEM). Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Similarly, platelets at the activation by low agonist concentration showed a significant increase in the phosphorylation of Akt via Gi signaling when plasma cholesterol concentration was elevated (Fig. 5A–D). On the other hand, at sub-maximal agonist stimulation a minimal difference was seen in the level of Akt phosphorylation among the 5 different subgroups. In all of these western blot experiments platelets were preincubated with indomethacin to block TXA2 synthesis in order to evaluate the level of ERK and Akt phosphorylation induced by the primary receptor signaling.

Discussion

Increased platelet reactivity has been widely described in patients with hyperlipidemia in several clinical studies [7,8,17–19,31,34–36,41]. Lipid metabolic disorders alone or along with other comorbidities such as hyperglycemia may initiate the development of atherosclerotic processes and subsequently increased platelet responses to distinct stimuli [4,6,31]. Although platelets are activated by a number of substances, the response of platelets results in a similar sequence of actions such as the release of the contents of dense and α-granules (especially P-selectin, CD40L and IL-1β) along with increased thromboxane generation [4]. In addition, platelets intensively adhere to injured endothelial cells and interact with leukocytes under these conditions. Overall, reactive platelets may contribute to the progression of atherosclerosis and related arterial thrombosis [32]. Antiplatelet therapies, especially P2Y12 receptor antagonists, have been recognized as a critical and effective treatment in decreasing the risk of myocardial infarction, cardiovascular death or any revascularization in coronary artery disease or DM with hypercholesterolemia [17–19]. Moreover, statins, beyond lowering the level of lipoproteins, showed several additional beneficial effects with anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antithrombotic abilities e.g. by decreasing the cholesterol content of platelet membranes [33,34]. Several clinical studies have demonstrated the efficacy of anti-lipid therapy in decreasing platelet activation and the risk for related vascular events in humans [35,36], or in animals [37] with hypercholesterolemia. In contrast, others showed no effect of lipid lowering in cardiovascular disease or type 2 DM [38,39]. On the other hand, signaling mechanisms targeted by different antiplatelet therapies that may be responsible for platelet hyperreactivity in hypercholesterolemia, have not been fully evaluated.

The purpose of this study was to characterize the contribution of the P2Y12 receptor-mediated pathway in the propagation of increased platelet reactivity affected by mild or severe cholesterolemic disorder. We generated differently elevated plasma cholesterol levels in animal models, in which LDLR−/− and WT mice were fed on standard chow and two types of high-fat diets for 8 weeks. In comparison to previous animal studies [20,21,26] this feeding period can be considered as a short exposure of platelets to hypercholesterolemia to elevate cholesterol levels. Mice with 2–3 fold-increased cholesterol levels were consistent with humans suffering from obesity-associated hypercholesterolemia or in subclinical metabolic or vascular disease [4,5]. However, LDLR−/− mice on the Western diet showed a 10-fold elevation in cholesterol level, which were relevant to patients with extreme cholesterol levels in familial hypercholesterolemia [7]. Under these conditions, such a long exposure of hypercholesterolemia could result in endothelial cell damage and inflammation. However, the present studies performed with ex vivo washed platelets did not involve these additional factors. Any in vivo thrombosis experiments would have to take into account such additional physiological changes. We investigated platelet aggregation, both dense- and α-granule secretion, and αIIbβ3 receptor activation in washed murine platelets stimulated downstream of the P2Y12 receptor using 2MeSADP and indirectly by a PAR4 agonist. To gain insight into the intracellular signaling events mediated by the Gi-coupled pathway, the levels of ERK and Akt phosphorylation were also determined. Results from hypercholesterolemic mice with distinctly elevated cholesterol levels were compared to those from normocholesterolemic animals.

We found that due to the increased response to 2MeSADP and AYPGKF, agonist-induced platelet aggregation was augmented along with significantly higher levels of ATP secretion and αIIbβ3 receptor activation, which were evident when platelets were stimulated by the lower concentration of agonists. Furthermore, P-selectin expression, a sensitive marker of platelet activation [40], was also enhanced in hypercholesterolemic mice, as similarly measured in patients [31,41], but did not show statistically significant change in WT mice on Western diet and LDLR−/− mice on chow diet compared to control animals (see Fig. 2B). Hence P2Y12 signaling seems to be more required for integrin activation and dense granule secretion, and it might be less necessary for α-granule release under such conditions. Platelet hyperreactivity was mediated via the P2Y12 receptor coupled Gi signaling with increased level of ERK and Akt phosphorylation in hypercholesterolemic mice compared to normal controls. Since Akt is involved in the regulation of αIIbβ3 receptor activation, increased Akt phosphorylation promoted a larger number of activated αIIbβ3 receptors demonstrated by higher level of JON/A binding in abnormal mice.

TXA2 generation showed a significant elevation along with increasing cholesterol levels in dyslipidemic animals versus normocholesterolemic mice. ERK is considered as an important mediator of activation of cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2). Thus, increased TXA2 generation was partly due to the elevated ERK phosphorylation. Shankar et al. published that P2Y12 receptor antagonism (e.g. due to clopidogrel) resulted in a significant inhibition of PAR-induced TXA2 generation because of the interference with the activity of cPLA2 [23]. These data support our current findings on amplified TXA2 generation via increased P2Y12 receptor-coupled signaling in hypercholesterolemia. However, it is clear that abnormal TXA2 generation contributed to but did not exclusively result in platelet hyperreactivity since platelet responses were still enhanced even in the absence of TXA2 synthesis. The use of the P2Y12 receptor antagonist AR-C69931MX in indomethacin-pretreated platelet samples resulted in strongly reduced platelet aggregation in hypercholesterolemic mice versus healthy controls. These data suggest that there are enhanced benefits of the P2Y12 receptor antagonist in patients with dyslipidemia.

In the last couple of years, a few studies have been published by other groups [11–13] suggesting the role of native and oxidized LDL-induced pathways in platelet activation via specific receptors ApoE-R2’ and CD36, respectively. Both pathways induced p38MAPK phosphorylation resulting in increased thromboxane generation, which is the main mediator of fibrinogen receptor activation [42]. This generated thromboxane acts synergistically with other signaling processes mediated by other (classical) agonists. We did not exclude the role of other lipid metabolites such as oxLDL in platelet activation. However, we claim that P2Y12 receptor signaling is one of the important signaling pathways, which contributes to platelet hyperreactivity in hypercholesterolemia. We think that the contribution of P2Y12 receptor pathway in hypercholesterolemia was proved by those experiments involving direct blockade of P2Y12 receptor with AR-C69931MX (Fig. 4G) in the absence of TXA2 generation (with indomethacin). When the P2Y12 pathway was still functional but no thromboxane was generated (Fig. 4A+B), again there was significant difference in aggregation among the different subgroups.

Similarly to our work, the role of P2Y12 receptor-coupled events in thrombosis was previously analyzed in ApoE-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice with a dyslipidemic phenotype. Clopidogrel treatment attenuated atheroma development in these mice [43]. This receptor was also suggested to induce signaling as a mediator of the adverse consequences of smoke exposure in ApoE−/− mice when the specific antagonist cangrelor decreased in vivo thrombus formation [44]. These findings support our results showing that the P2Y12 receptor is highly involved in the regulation of several functional responses in dyslipidemic condition. In addition, Evan et al [45] recently described that platelet P2Y12 receptor influenced the vessel wall response to FeCl3 arterial injury and thrombosis when the neointima formation in the arteries of P2Y12−/− mice was significantly less than that observed in the vessels in littermate controls. This may be another response that might be promoted by hypercholesterolemia via P2Y12 receptor.

The implication of lipid rafts in sustaining the mechanical link with different platelet signaling events remains to be studied. Cholesterol-enriched membrane microdomains are strongly associated with the coordination of platelet activation mechanisms [46]. The disruption of lipid rafts by cholesterol depletion prevented actin polymerization and tyrosine phosphorylation events in platelets, and in turn, exogenous phospholipids caused a modulation in the activation of signaling [47]. A diet rich in saturated fatty acids affected membrane cholesterol/phospholipid ratio and phospholipase C-mediated platelet activation in rat platelets, and relatively small changes in cholesterol content had a more profound influence on platelet activation than substantial changes in arachidonate level [9]. It is noted that the hyperreactivity of platelets in our experiments might also result from the increased P2Y12 receptor expression upon prolonged hypercholesterolemia, but we could not evaluate the changes in the receptor number in these mice.

In this study, we first demonstrated that P2Y12 receptor pathway significantly amplified platelet responses such as aggregation, secretion and activation of αIIbβ3 receptor via thromboxane-dependent and -independent manner even in the presence of mildly increased plasma cholesterol and not just at extremely high values. We also provided evidence on the mechanism in that platelet reactivity downstream of the P2Y12 receptor was enhanced via significantly elevated ERK and Akt phosphorylation even if TXA2 generation did not contribute to platelet activation. The cholesterol levels in these mice were similar to those in humans with obesity-related or homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia; therefore these mice offered an appropriate model to evaluate platelet hyperreactivity in such patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by HL81322, HL93231, and HL60683 from the National Institutes of Health (S. P. K.). We gratefully acknowledge Ms. Pierrette Andre (Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA) for her technical assistance. We also thank Dr. Janos Kappelmayer (University of Debrecen, Hungary) for critically reviewing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflict of Interests

The authors state that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Carvalho AC, Colman RW, Lees RS. Platelet function in hyperlipoproteinemia. N Eng J Med. 1974;290:434–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197402212900805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shattil SJ, Anaya-Galindo R, Bennett J, Colman RW, Cooper RA. Platelet hypersensitivity induced by cholesterol incorporation. J Clin Invest. 1975;55:636–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI107971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tremoli E, Colli S, Maderna P, Baldassarre D, Di Minno G. Hypercholesterolemia and platelets. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1993;19:115–21. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferroni P, Basili S, Davi G. Platelet activation, inflammatory mediators and hypercholesterolemia. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2003;1:157–69. doi: 10.2174/1570161033476772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lacoste L, Lam JY, Hung J, Letchacovski G, Solymoss CB, Waters D. Hyperlipidemia and coronary disease. Correction of the increased thrombogenic potential with cholesterol reduction. Circulation. 1995;92:3172–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.11.3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;420:868–74. doi: 10.1038/nature01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davi G, Averna M, Catalano I, Barbagallo C, Ganci A, Notarbartolo A, Ciabattoni G, Patrono C. Increased thromboxane biosynthesis in type IIa hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 1992;85:1792–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.5.1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calkin AC, Drew BG, Ono A, Duffy SJ, Gordon MV, Schoenwaelder SM, Sviridov D, Cooper ME, Kingwell BA, Jackson SP. Reconstituted high-density lipoprotein attenuates platelet function in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus by promoting cholesterol efflux. Circulation. 2009;120:2095–104. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.870709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heemskerk JW, Feijge MA, Simonis MA, Hornstra G. Effects of dietary fatty acids on signal transduction and membrane cholesterol content in rat platelets. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1255:87–97. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(94)00225-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prociuk MA, Edel AL, Richard MN, Gavel NT, Ander BP, Dupasquier CM, Pierce GN. Cholesterol-induced stimulation of platelet aggregation is prevented by a hempseed-enriched diet. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;86:153–9. doi: 10.1139/Y08-011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korporaal SJ, Relou IA, van Eck M, Strasser V, Bezemer M, Gorter G, van Berkel TJ, Nimpf J, Akkerman JW, Lenting PJ. Binding of low-density lipoprotein to platelet apolipoprotein E receptor 2' results in phosphorylation of p38MAPK. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52526–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407407200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Korporaal SJ, Van Eck M, Adelmeijer J, Ijsseldijk M, Out R, Lisman T, Lenting PJ, Van Berkel TJ, Akkerman JW. Platelet activation by oxidized low-density lipoprotein is mediated by CD36 and scavenger receptor-A. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2476–83. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.150698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen K, Febbraio M, Li W, Silverstein RL. A specific CD36-dependent signaling pathway is required for platelet activation by oxidized low-density lipoprotein. Circ Res. 2008;102:1512–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.172064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quinton TM, Kim S, Jin J, Kunapuli SP. Lipid rafts are required in Galpha(i) signaling downstream of the P2Y12 receptor during ADP-mediated platelet activation. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:1036–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savi P, Zachayus JL, Delesque-Touchard N, Labouret C, Herve C, Uzabiaga MF, Pereillo JM, Culouscou JM, Bono F, Ferrara P, Herbert JM. The active metabolite of Clopidogrel disrupts P2Y12 receptor oligomers and partitions them out of lipid rafts. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11069–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510446103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dorsam RT, Kunapuli SP. Central role of the P2Y12 receptor in platelet activation. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:340–5. doi: 10.1172/JCI20986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitka M. Results of CURE trial for acute coronary syndrome. Jama. 2001;285:1828–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehta SR, Yusuf S, Peters RJ, Bertrand ME, Lewis BS, Natarajan MK, Malmberg K, Rupprecht H, Zhao F, Chrolavicius S, Copland I, Fox KA. Effects of pretreatment with clopidogrel and aspirin followed by long-term therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the PCI-CURE study. Lancet. 2001;358:527–33. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05701-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Angiolillo DJ, Capranzano P, Desai B, Shoemake SB, Charlton R, Zenni MM, Guzman LA, Bass TA. Impact of P2Y(12) inhibitory effects induced by clopidogrel on platelet procoagulant activity in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Thromb Res. 2009;24:318–22. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cyrus T, Sung S, Zhao L, Funk CD, Tang S, Pratico D. Effect of low-dose aspirin on vascular inflammation, plaque stability, and atherogenesis in low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Circulation. 2002;106:1282–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000027816.54430.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roselaar SE, Kakkanathu PX, Daugherty A. Lymphocyte populations in atherosclerotic lesions of apoE −/− and LDL receptor −/− mice. Decreasing density with disease progression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16:1013–8. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.8.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim S, Jin J, Kunapuli SP. Akt activation in platelets depends on Gi signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4186–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306162200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shankar H, Garcia A, Prabhakar J, Kim S, Kunapuli SP. P2Y12 receptor-mediated potentiation of thrombin-induced thromboxane A2 generation in platelets occurs through regulation of Erk1/2 activation. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4 :638–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waheed AA, Jones TL. Hsp90 interactions and acylation target the G protein Galpha 12 but not Galpha 13 to lipid rafts. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32409–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200383200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim S, Foster C, Lecchi A, Quinton TM, Prosser DM, Jin J, Cattaneo M, Kunapuli SP. Protease-activated receptors 1 and 4 do not stimulate G(i) signaling pathways in the absence of secreted ADP and cause human platelet aggregation independently of G(i) signaling. Blood. 2002;99:3629–36. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu L, Stalker TJ, Fong KP, Jiang H, Tran A, Crichton I, Lee EK, Neeves KB, Maloney SF, Kikutani H, Kumanogoh A, Pure E, Diamond SL, Brass LF. Disruption of SEMA4D ameliorates platelet hypersensitivity in dyslipidemia and confers protection against the development of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1039–45. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.185405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paigen B, Morrow A, Brandon C, Mitchell D, Holmes P. Variation in susceptibility to atherosclerosis among inbred strains of mice. Atherosclerosis. 1985;57:65–73. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(85)90138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin J, Quinton TM, Zhang J, Rittenhouse SE, Kunapuli SP. Adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-induced thromboxane A(2) generation in human platelets requires coordinated signaling through integrin alpha(IIb)beta(3) and ADP receptors. Blood. 2002;99:193–8. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia A, Shankar H, Murugappan S, Kim S, Kunapuli SP. Regulation and functional consequences of ADP receptor-mediated ERK2 activation in platelets. Biochem J. 2007;404:299–308. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dangelmaier C, Jin J, Smith JB, Kunapuli SP. Potentiation of thromboxane A2-induced platelet secretion by Gi signaling through the phosphoinositide-3 kinase pathway. Thromb Haemost. 2001;85:341–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagy B, Jr, Csongrádi E, Bhattoa HP, Balogh I, Blaskó G, Paragh G, Kappelmayer J, Káplár M. Investigation of Thr715Pro P-selectin gene polymorphism and soluble P-selectin levels in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Thromb Haemost. 2007;98:186–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Massberg S, Brand K, Grüner S, Page S, Müller E, Müller I, Bergmeier W, Richter T, Lorenz M, Konrad I, Nieswandt B, Gawaz M. A critical role of platelet adhesion in the initiation of atherosclerotic lesion formation. J Exp Med. 2002;196:887–96. doi: 10.1084/jem.20012044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenson RS, Tangney CC. Anti-atherothrombotic properties of statins: implications for cardiovascular event reduction. Jama. 1998;279:1643–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.20.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Notarbartolo A, Davi G, Averna M, Barbagallo CM, Ganci A, Giammarresi C, La Placa FP, Patrono C. Inhibition of thromboxane biosynthesis and platelet function by simvastatin in type IIa hypercholesterolemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:247–51. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osamah H, Mira R, Sorina S, Shlomo K, Michael A. Reduced platelet aggregation after fluvastatin therapy is associated with altered platelet lipid composition and drug binding to the platelets. Brit J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;44:77–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1997.00625.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Puccetti L, Pasqui AL, Pastorelli M, Bova G, Cercignani M, Palazzuoli A, Angori P, Auteri A, Bruni F. Time-dependent effect of statins on platelet function in hypercholesterolaemia. Eu J Clin Invest. 2002;32:901–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2002.01086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anderson HV, McNatt J, Clubb FJ, Herman M, Maffrand JP, DeClerck F, Ahn C, Buja LM, Willerson JT. Platelet inhibition reduces cyclic flow variations and neointimal proliferation in normal and hypercholesterolemic-atherosclerotic canine coronary arteries. Circulation. 2001;104:2331–7. doi: 10.1161/hc4401.098434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malmstrom RE, Settergren M, Bohm F, Pernow J, Hjemdahl P. No effect of lipid lowering on platelet activity in patients with coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance. Thromb Haemost. 2009;101:157–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Broijersen A, Eriksson M, Leijd B, Angelin B, Hjemdahl P. No influence of simvastatin treatment on platelet function in vivo in patients with hypercholesterolemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:273–8. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kappelmayer J, Nagy B, Jr, Miszti-Blasius K, Hevessy Z, Setiadi H. The emerging value of P-selectin as a disease marker. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2004;42:475–86. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2004.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davi G, Romano M, Mezzetti A, Procopio A, Iacobelli S, Antidormi T, Bucciarelli T, Alessandrini P, Cuccurullo F, Bittolo Bon G. Increased levels of soluble P-selectin in hypercholesterolemic patients. Circulation. 1998;97:953–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.10.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akkerman JWN. From low-density lipoprotein to platelet activation. Internal J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:2374–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Afek A, Kogan E, Maysel-Auslender S, Mor A, Regev E, Rubinstein A, Keren G, George J. Clopidogrel attenuates atheroma formation and induces a stable plaque phenotype in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Microvasc Res. 2009;77:364–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dong A, Caicedo J, Han SG, Mueller P, Saha S, Smyth SS, Gairola CG. Enhanced platelet reactivity and thrombosis in Apoe−/− mice exposed to cigarette smoke is attenuated by P2Y12 antagonism. Thromb Res. 2010;126:312–7. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Evans DJ, Jackman LE, Chamberlain J, Crosdale DJ, Judge HM, Jetha K, Norman KE, Francis SE, Storey RF. Platelet P2Y(12) receptor influences the vessel wall response to arterial injury and thrombosis. Circulation. 2009;119:116–22. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.762690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bodin S, Tronchere H, Payrastre B. Lipid rafts are critical membrane domains in blood platelet activation processes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1610:247–57. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Larive RM, Baisamy L, Urbach S, Coopman P, Bettache N. Cell membrane extensions, generated by mechanical constraint, are associated with a sustained lipid raft patching and an increased cell signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1798:389–400. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]