Abstract

Objective

To qualitatively explore potential mechanisms that may confer heightened risk for HIV infection among survivors of sex trafficking in India.

Methods

Case narratives of 61 repatriated women and girls who reported being trafficked into sex work and were receiving services at an NGO in Mysore, India, were reviewed. Narratives were analyzed to examine potential sources of HIV risk related to sex trafficking.

Results

Participants were aged 14–30 years. Among the 48 women and girls tested for HIV, 45.8% were HIV positive. Narratives described very low levels of autonomy, with control exacted by brothel managers and traffickers. Lack of control appeared to heighten trafficked women and girls’ vulnerability to HIV infection in the following ways: use of violent rape as a means of coercing initiation into sex work, inability to refuse sex, inability to use condoms or negotiate use, substance use as a coping strategy, and inadequate access to health care.

Conclusion

Sex trafficked women and girls lack autonomy and are rendered vulnerable to HIV infection through several means. Development of HIV prevention strategies specifically designed to deal with lack of autonomy and reach sex-trafficked women and girls is imperative.

Keywords: HIV, India, Sex trafficking, Sex work, South Asia, Violence

1. Introduction

According to the UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress, and Punish Trafficking in Persons, sex trafficking is “…the recruitment, transfer, harboring, or receipt of persons via threat, force, coercion, abduction, fraud, or deception and/or for the purpose of sexual exploitation, including prostitution” [1]. Among the deleterious health consequences affecting women and girls subjected to sex trafficking (e.g. post traumatic stress disorder, sexually transmitted infections [STIs], gynecological infections, tuberculosis [2–5]), the threat of HIV infection is of tremendous public health importance in India. This country is currently grappling with one of the largest HIV epidemics in the world [6], and is also believed to be the destination for some 150 000 women and girls who are trafficked across South Asia each year [7]. While research regarding HIV among sex-trafficked populations is in its early phases, multiple investigations focused on South Asia have documented that 22% to 38% of sex-trafficked women may be HIV positive [3,8,9]. These seroprevalence figures fall within the higher range of the HIV prevalence estimates among female sex workers (FSWs) recently documented by the India AIDS Initiative, Avahan, which ranged from 3.1% to 40.0% [10]. These data suggest heightened vulnerability to HIV among trafficked women and underscore the critical need for research to examine factors that may confer such elevated risk.

Sex trafficking is a dire human rights violation and represents one of the most extreme forms of female sex work. Thus, factors that are likely to increase the threat of HIV infection among all FSWs are believed to be more extreme among women and girls who have been sex trafficked [8,9]. Specifically, sex-trafficked women and girls have been shown to experience alarmingly high rates of physical and sexual violence. Recent data indicate that women and girls who entered sex work via trafficking were over 7 times more likely to report experiencing violence in brothels than FSWs who were not identified as trafficked [11]. Other research has documented the prevalence of violence during both the trafficking process and while in sex work to be as high as 95% [2]. Such experiences of violence are believed to diminish possibilities for condom use and increase the potential for injuries (e.g. vaginal trauma or laceration) that may facilitate HIV acquisition [8,9,12,13]. Younger age may also contribute to HIV vulnerability: half of all trafficked women are believed to be under 18 years old [14] and prior research has documented higher HIV infection among younger survivors of sex trafficking [8,9]. To date, however, there has been limited public health research directly investigating such theorized mechanisms.

The purpose of the present study was to explore the existence and operation of mechanisms by which risk for HIV infection is heightened among sex-trafficked women and girls in India.

2. Materials and methods

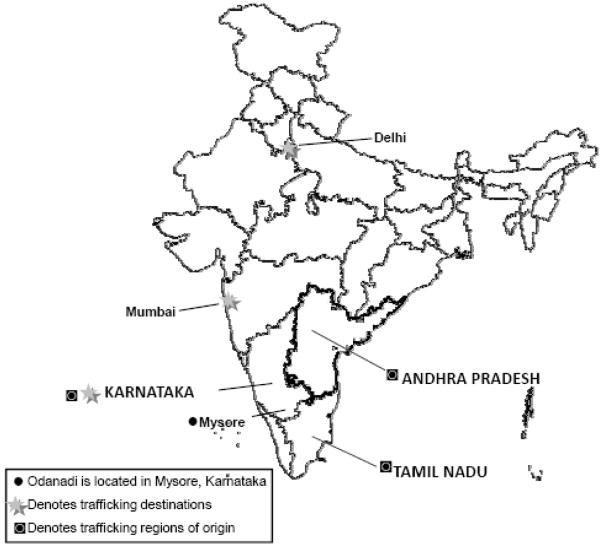

All de-identified case records obtained from survivors of sex trafficking presenting to Odanadi Seva Trust (Mysore, Karnataka, India; Fig. 1) between February 2002 and April 2006 were collected by the US-based investigative team in March 2007 (n=71). Odanadi is a nongovernmental organization (NGO) providing shelter and care to vulnerable women and girls from the South Indian state of Karnataka. Odanadi is also part of a larger network of NGOs throughout South Asia (namely India, Nepal, Bangladesh) whose activities focus on service provision (e.g. counseling, general health care, job training) for survivors of sex trafficking. As women and girls exit sex work (often through release efforts coordinated by such NGOs and police), they are placed within the care of network member NGOs who operate near the trafficking destination for short-term care. The local NGOs then work to repatriate survivors of sex trafficking to longer-term facilities within their regions of origin. For example, Odanadi provides longer-term assistance to those trafficked from Karnataka; it also provides services to women and children who have been abandoned, face mental illness, or experience family violence.

Figure 1.

Map of India highlighting Odanadi, regions of origin, and trafficking destinations.

The study involved a retrospective qualitative analysis of information collected through a routine intake interview at Odanadi. Intake interviews are conducted upon initial entry into care by trained counselors working as case managers. Interviews seek to obtain information regarding basic demographics, trafficking history, and experience of forced prostitution (i.e. entering sex work via trafficking) as part of an overall assessment to determine service needs. Case managers record all testimony into case records. As the interviews were conducted as part of routine assessment of service needs (i.e. not for research purposes), the case managers did not receive training in qualitative research methodology, and no specific “research instrument” or guide was used. All case managers took detailed notes (in Kannada) during interviews; these notes comprised the case narratives, which were then analyzed by the US-based investigative team. Because of the service-based nature of Odanadi, the case narratives do not always include verbatim accounts of interviews, and may also include summaries as noted by case managers.

As part of the regular service provision at Odanadi, all survivors of sex trafficking undergo an HIV test conducted by one of Odanadi’s partner hospitals in Mysore. All case managers obtain verbal consent from the individuals prior to arranging an HIV test. HIV serological testing is conducted via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or Western Blot; results of laboratory testing were recorded in the case records.

Of the 71 case records obtained by the US-based investigative team, 10 were excluded because these individuals were receiving services at Odanadi for reasons other than sex trafficking. The sample was restricted to women and girls who were documented as being trafficked into sex work by either the police in the trafficking destination city (as indicated in their case record) or by Odanadi case managers (n=61).

Narratives recorded by case managers in Kannada, the main language spoken in the South Indian state of Karnataka, were translated into English by case managers. Codes were developed through an iterative process, using a grounded theory approach [15]. All case record narratives were reviewed and coded separately by the first and senior authors (JG and JS). Coding occurred until saturation was reached regarding themes related to HIV risk. The first author finalized the coding in cases involving interpretation differences. Coded case narratives were then discussed with the larger investigative team to further refine identified themes.

The study did not involve direct contact with human subjects. All study protocols were approved by the Harvard School of Public Health Human Subjects Committee.

3. Results

Participants were aged between 14 and 30 years. The mean age at initial trafficking was 17 years. Over half of all women and girls (57.4%) were trafficked under the pretense of false economic opportunities (i.e. told by the trafficker that they would be starting a job such as a housemaid or factory worker). None of the women and girls in the sample reported being told by traffickers that they were going to go into sex work. While nearly 40% of the trafficking agents were strangers, over half were nonstrangers (e.g. acquaintances, family members, husbands, or co-workers). Over three-quarters (78.7%) of women and girls were tested for HIV; among these, 45.8% were found to be HIV positive. The remaining demographics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics, sex-trafficking experiences, and HIV status among the study group (n=61)

| Variable | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age at trafficking, y (mean, 17 years) | |

| <14 | 7 (11.5) |

| 15–17 | 19 (31.1) |

| >18 | 16 (26.2) |

| Missing data | 19 (31.1) |

| Region of origin | |

| Karnataka | 50 (82.0) |

| Tamil Nadu | 2 (3.3) |

| Andhra Pradesh | 1 (1.6) |

| Other | 2 (3.3) |

| Missing data | 6 (9.8) |

| Pre-trafficking marital status | |

| Unmarried | 38 (62.3) |

| Married | 9 (14.8) |

| Separated | 3 (4.9) |

| Abandoned | 5 (8.2) |

| Missing data | 6 (9.8) |

| Primary tactic used for trafficking | |

| False economic opportunity (e.g. housemaid job) | 35 (57.4) |

| Kidnapped using drugs | 8 (13.1) |

| Tricked into social activity (e.g. visit relative) | 7 (11.5) |

| False offer of shelter | 3 (4.9) |

| False marriage | 1 (1.6) |

| Brutal kidnapping (without drugs or other tactic) | 1 (1.6) |

| Missing data | 6 (9.8) |

| Relationship with trafficker | |

| Stranger | 24 (39.3) |

| Friend, neighbor, or acquaintance | 11(18.0) |

| Relative or family friend | 6 (9.8) |

| Co-worker | 5 (8.2) |

| Husband/intimate partner | 3 (4.9) |

| Missing data | 12 (19.7) |

| Trafficking destination (see Fig. 1) | |

| Mumbai | 32 (52.5) |

| Delhi | 16 (26.2) |

| City in Karnataka | 7 (11.5) |

| Missing data | 6 (9.8) |

| Duration in forced prostitution (median, 18 months) | |

| ≤ 1 mo. | 2 (3.3) |

| 2–6 mo. | 5 (8.2) |

| 7–1 y | 6 (9.8) |

| 1–5 y | 21 (34.4) |

| >5 y | 2 (3.3) |

| Missing data | 25 (41.0) |

| Tested for HIV a,b,c | |

| Yes | 48 (78.7) |

| No | 13 (21.3) |

| HIV status (among those tested) | |

| Positive | 22 (45.8) |

| Negative | 26 (54.2) |

Using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, Western Blot, or rapid testing.

A series of Fisher exact tests revealed no significant demographic differences at the P<0.05 level between women and girls who were tested for HIV and those who were not.

No information is available regarding reasons for not having an HIV test.

Qualitative findings of the various themes identified are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of key themes in the context of sex trafficking and HIV vulnerability

| Themes | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Theme 1: Sex-trafficked women and girls lack autonomy | “Two ladies asked her what was wrong and she told them that she needed a job. They told her that they knew a person who can get her a job in a garment factory, but the person is leaving today. So, she agreed to go with them. They reached Mumbai and told her that it was her sister’s house, but it was really a brothel on Grant Road.” “She met a lady at the bus stop who offered her a job of housemaid at Delhi. She trusted that woman and agreed to go. After reaching Delhi, that woman kept her in a house for a week, then sent her with another female, who took her to the brothel on G.B. Road.” “He [her husband] brought her to Delhi. She asks for him [her husband]. The gharwali tells her that he is no longer her husband. He sold her and now he is gone.” “He [the trafficker] sold her for Rs 40,000 to a gharwali. When she requested the gharwali to send her to her mother, the gharwali refused by saying that she had to repay the debt if she wants to go back.” “She was threatened that if she did not do the work, she would be kept there for 3 years instead of 1 year.” |

| Theme 2: Rape as a tool for initiation into sex work | “She said that she was completely lost and was just holding the woman’s [the trafficker] hand with fear. The woman went out and sent a man inside who pushed her to the bed, opened his clothes, removed his pant, and forced her to make love with him. She shouted and cried but no one came to help. She got scared that it was bleeding from her vagina, and requested the women [the gharwali] to give her some medicine. She says that she was forced in the above manner for about 4–5 days.” “She was gang raped by 5 persons and this heinous act continued until she gave her consent to be a prostitute.” “They handed her over to the gharwali. She was very cruel and rude. As soon as she was sent there, she was asked to dress herself and apply make-up. Then, four girls entered the room and held down her hands and legs and helped that man to have sexual intercourse with her. At that time, she said that she was crying out of stomach pain and fainted on seeing blood due to forceful intercourse.” |

| Theme 3: Chronic sexual violence and inability to refuse sex | “She says that she used to be beaten up when she wore full dresses.” “She got beats and scolding from the brothel keepers regularly. She is even burnt with the cigarette buds.” “When (she) would refuse to sleep with them [male clients], the gharwali would hit (her) properly.” “Refusal to carry on the work resulted in severe punishments and torture.” |

| Theme 4: Chronic sexual violence and inability to negotiate condom use | “The customers used to drink and some used to refuse to use condoms. As a result of this, she conceived three times.” “Some of the customers would refuse to take any precautions like using condoms. If she tried, the gharwali would hit her properly.” “When the blood result came, she understood that she is HIV positive. Then I asked whether she was using condoms. For this she replied that many customers never wanted to use the condoms and if she forced them they used to complain to the gharwali who in turn tortured her.” |

| Theme 5: Substance use | “He came there tied up her hands and legs and forced her to drink. The gharwali threatened her that she would throw her out of the building if she wouldn’t sleep. She was unconscious and was raped.” “She got addicted to alcohol and pan parag, as she was forced to drink along with the customers.” “She had to go with more than 15 customers per day, and during night time she had to entertain at least 2 men. Unable to bear the work pressure, she got addicted to alcohol and betel nut chewing.” |

| Theme 6: Inability to access health care | “She once fell sick and no one took care of her. She was thrown in a corner for about 15 days and none of them bothered about her.” “She always had health problems while her stay in the brothel, but she was hardly ever taken care of. Once she had severe stomach pain and she was crying, but the gharwali neglected it. Only when the pain went out of control was she taken to the doctor.” “Once, I had a high fever. I was unable to talk due to the fever. I was shivering with cold, and my throat was parched. Although I protested that I could not possibly do anything, I was forced to sleep with the customers.” “She got vaginal infection and started bleeding and the part got swollen. She refused, but the gharwali did not listen and sent her to the customers. After going with customers for about 10 days, there were lots of pimple type structures full of her puberty areas. For this, she struggled for about 6 months.” |

Theme 1: Sex-trafficked women and girls lack autonomy

Overall, the case narratives consistently illustrated that sex-trafficked women experienced removal of their basic autonomy. Women and girls were brought to brothels and other sex work venues via threats or deceit without any a priori knowledge that they were entering sex work.

Upon arrival at sex work venues, trafficking agents negotiated the “selling” of women and girls to “gharwalis” (i.e. brothel managers), and debt bondage was established (i.e. sex trafficking victims became “property” of the gharwali; in order to leave debt bondage, women and girls were required to engage in sex work to earn money to buy back their freedom). Threats and intimidation were often used by gharwalis to restrict the movement and actions of the trafficked women and girls. This lack of control heightened trafficked women and girls’ vulnerability to HIV infection in the following ways: use of violent rape as a means of coercing initiation into sex work, inability to refuse sex, inability to negotiate condom use, substance use as a coping strategy, and inadequate access to health care.

Theme 2: Rape as a tool for initiation into sex work

Strikingly, all women and girls trafficked into sex work, without exception, described being initiated into sex work through rape. Often, such violence took place almost immediately upon their arrival to the brothel (or other venue for sex work) at the point where women and girls learned that they had unknowingly been “sold” to a gharwali. In many cases, the trafficker or gharwali appeared to prearrange the initial male clients, who then forcefully and repeatedly raped the victim. Other FSWs also appeared to actively participate in the forced sexual initiation of trafficking victims by using physical violence or restraint to facilitate the rape.

Theme 3: Chronic sexual violence and inability to refuse sex

Beyond initial entry into sex work, the case narratives revealed how sex-trafficked women and girls chronically experienced violence. Specifically, gharwalis would regularly use violence against them to maintain ongoing control over their choice of clothing. In other instances, the narratives discussed how the gharwali would use violence against women and girls if they refused to have sex with male clients.

Theme 4: Chronic sexual violence and inability to negotiate condom use

While the case narratives described how trafficked women and girls engaged in sex work on demand, condom use was rarely mentioned. When it was discussed, inconsistent use was described, with male clients being unwilling in general to use condoms. Attempts to negotiate condom use were met with violent repercussions as male clients would notify the gharwalis, who in turn would physically beat the trafficking victims. Thus, demanding or negotiating condom use with male clients was not possible and offered little personal benefit to these women and girls, even in the case of HIV-infected women.

Theme 5: Substance use

The case narratives described how trafficked women and girls were forced to consume alcohol by the gharwalis to facilitate rape or as a means of socializing with male clients. The use of additional substances, including betel nuts and pan parag (substances commonly used in South Asia and associated with addictive properties [16]), were also discussed. Sex-trafficked women and girls discussed the use of these local substances, as well as alcohol, as a means of coping with the chronic violence.

Theme 6: Inability to access health care

Women and girls commonly experienced severe illnesses during forced sexual servitude. These health concerns appeared to be largely neglected by the gharwali. Moreover, the gharwali appeared to have control over the movement of trafficked women and girls, and thus their access to health care. Health problems appeared to be addressed by the gharwali only once the illnesses appeared to progress to the point of being dire. Despite these health concerns, they were required by the gharwali to continue to have sex with male clients, even in situations where their symptoms were indicative of STI infection.

4. Discussion

As with other studies of sex-trafficked women and girls in South Asia [3,4,8,9] the present study documents a substantially high seroprevalence of HIV (45.8%) in this population of predominantly Karntakan women and girls released from sex trafficking and receiving assistance at Odanadi. Furthermore, narratives illustrate how the context of sex trafficking heightens HIV risk. Specifically, experiences with extreme sexual violence as a tool to initiate individuals into sex work (i.e. gain compliance), the inability to refuse sex or negotiate condom use, and the inability to obtain health care appeared to place these women and girls directly at risk for HIV. The narratives also suggested the importance of substance use, both in the form of forced consumption as well as a means of coping with the sexual and physical violence they were made to endure; substance use may further heighten HIV vulnerability among victims of sex trafficking.

Given the confluence of fear, violence, and lack of autonomy described within the context of sex trafficking, it is questionable whether HIV prevention strategies relying solely on the ability of FSWs to negotiate and demand condom use with male clients are effective among sex-trafficked women and girls [13,14]. In addition, HIV prevention strategies that depend upon brothel owner enforcement of condom use among male clients may be similarly limited based on the current data. Central to the success of such approaches is engagement with brothel owners to convince them of the value and profits associated with keeping FSWs healthy and free of disease [17]. However, in the case of sex-trafficked women and girls, brothel owners may be more concerned with associated costs, which include having to pay nearly double the rate to “buy” younger girls from traffickers in response to the demands of male clients for younger girls [18]. Thus, to fully profit from their “investment,” brothel owners may place the interests of paying male clients above the health of FSWs [19], a situation likely exacerbated in cases of trafficked girls. Attempts to engage brothel owners in focusing on longer-term profit goals that can be derived from preserving the health of FSWs must also overcome the steady supply of young trafficking victims reported in this region [14] and the relatively low risk of prosecution for forcibly prostituting such individuals [18]. Further research related to development of HIV prevention programming in this context is needed.

Consistent with previous work with young, debt-bonded FSWs in Southeast Asia [20], sex-trafficked women and girls in the present study faced obstacles from brothel managers in obtaining access to health care. Considering the illegal nature of sex trafficking, brothel managers are likely to ensure that sex-trafficked victims remain hidden from authorities, including healthcare professionals [21,22]. Thus, existing HIV-focused interventions and programming (e.g. VCT clinics, NGO-led support groups) that may be successful among general populations of FSWs (i.e. those with relatively more personal freedom) may be inaccessible to sex-trafficked women and girls because of restrictions on movement outside of brothels [23]. These restrictions are likely to pose barriers to accessing health programs even in situations where attempts are made by public health professionals to build rapport with brothel owners, as documented among young, debt-bonded FSWs in Cambodia [20]. This inability to obtain treatment may place trafficked women and girls at greater risk for HIV infection.

The findings of the present study are best considered in the context of the following limitations. This work is limited by the small sample size of case records, thus results may not be generalizable to the larger population of sex-trafficked victims from either Karnataka or other Indian states. Nonetheless, the themes gleaned from case narratives are consistent with the few studies that have been conducted with younger and/or debt-bonded populations [11,20,24], as well as prior hypotheses concerning HIV vulnerability in the context of sex trafficking [8,9]. In addition, case records were reviewed from only one NGO, and women and girls cared for by other organizations may report different experiences. However, the sample includes women and girls who were trafficked to multiple destinations (e.g. Mumbai, Delhi, within Karnataka). Data were abstracted from case narratives that recorded the testimony of the sex-trafficked survivors at the time of intake into Odanadi. Thus, data may have been subject to error via caseworker detection or survivor recall. Moreover, the case narratives were not originally intended for research purposes, and were often recorded in the third person. Future research should seek to quantitatively corroborate the themes presented in this qualitative work.

Despite these limitations the current work provides critical insight into how the context of sex trafficking (e.g. violent initiation, lack of control over condom use) may place trafficked women and girls at high risk for HIV infection and potentially explain the high prevalence of HIV reported in earlier studies. While further research is needed to clarify these observations, current findings have several important implications for HIV prevention and intervention. These include broadening existing FSW-focused public health programs via development and implementation of HIV prevention strategies that can reach this highly vulnerable and hidden population. Also of paramount importance is increasing condom use among male clients, since reliance upon trafficked women and girls to negotiate condom use is likely to be ineffective and be met with violent repercussions.

Our qualitative findings also highlight the need for increased efforts to prevent sex trafficking in South Asia, including the release of women and girls who are forced into prostitution. Currently, the majority of such enterprises are conducted by antitrafficking NGOs, in conjunction with police operations. Another emerging model is FSW self-regulatory boards to monitor sex trafficking cases, without police involvement [25]. To date, neither approach has been formally evaluated regarding their ability to reduce trafficking. Development of effective and large-scale approaches to prevent sex trafficking is urgently needed to avert the brutal violence that is inflicted upon these women and girls and to minimize their risk for HIV infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US Department of State Trafficking in Persons Office (JS), Harvard Center for AIDS Research (JS, AR), Harvard South Asia Initiative (JS and JG), and the National Institute of Mental Health (JG) (T32MH020031). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.United Nations. United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress, and Punish Trafficking in persons, especially women and children, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime. In: Article 3 (a–d), G.A. res. 55/25, annex II, 55 U.S. (GAOR Supp. (No. 49) at 60, U.N. Doc. A/45/49 (Vol. I)); 2000.

- 2.Zimmerman C, Hossain M, Yun K, Gajdadziev V, Guzun N, Tchomarova M, et al. The health of trafficked women: a survey of women entering posttrafficking services in Europe. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):55–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.108357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsutsumi A, Izutsu T, Poudyal AK, Kato S, Marui E. Mental health of female survivors of human trafficking in Nepal. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(8):1841–7. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silverman JG, Decke MR, Gupta J, Dharmadhikari A, Seage GR, 3rd, Raj A. Syphilis and hepatitis B Co-infection among HIV-infected, sex-trafficked women and girls, Nepal. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(6):932–4. doi: 10.3201/eid1406.080090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dharmadhikari AS, Gupta J, Decker MR, Raj A, Silverman JG. Tuberculosis and HIV: a global menace exacerbated via sex trafficking. Int J Infect Dis. 2009 Jan 17; doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.11.010. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.UNAIDS. India Country Profile. Delhi, India: UNAIDS; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Congressional Research Service. Trafficking in Women and Children: The U.S. and International Response. Washington, DC: Library of Congress; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverman JG, Decker MR, Gupta J, Maheshwari A, Patel V, Raj A. HIV Prevalence and Predictors Among Rescued Sex-Trafficked Women and Girls in Mumbai, India. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006 doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243101.57523.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silverman JG, Decker MR, Gupta J, Maheshwari A, Willis BM, Raj A. HIV prevalence and predictors of infection in sex-trafficked Nepalese girls and women. JAMA. 2007;298(5):536–542. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.5.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Indian Council of Medical Research and Family Health International. National Interim Summary Report-India (October 2007), Integrated Behavioural and Biological Assessment (IBBA), Round 1 (2005–2007) New Delhi, India: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarkar K, Bal B, Mukherjee R, Chakraborty S, Saha S, Ghosh A, et al. Sex-trafficking, violence, negotiating skill, and HIV infection in brothel-based sex workers of eastern India, adjoining Nepal, Bhutan, and Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr. 2008;26(2):223–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willis BM, Levy BS. Child prostitution: global health burden, research needs, and interventions. Lancet. 2002;359(9315):1417–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08355-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beyrer C, Stachowiak J. Health consequences of the trafficking of women and girls in Southeast Asia. Brown Rev World Affairs. 2003;10(1):105–119. [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Department of State. Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000: Trafficking in Persons Report. Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glaser B, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benegal V, Rajkumar RP, Muralidharan K. Does areca nut use lead to dependence? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;97(1–2):114–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Human Rights Watch. Rape for Profit: Trafficking of Nepali Girls and Women to Indian Brothels. New York: Human Rights Watch; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nair PM. A report on trafficking of women and children in India: 2002–2003. I. New Delhi: UNIFEM, ISS, NHRC; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhave G, Lindan CP, Hudes ES, Desai S, Wagle U, Tripathi SP, et al. Impact of an intervention on HIV, sexually transmitted diseases, and condom use among sex workers in Bombay, India. Aids. 1995;9 (Suppl 1):S21–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Busza J, Schunter BT. From competition to community: participatory learning and action among young, debt-bonded Vietnamese sex workers in Cambodia. Reprod Health Matters. 2001;9(17):72–81. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(01)90010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barrows J, Finger R. Human trafficking and the healthcare professional. South Med J. 2008;101(5):521–4. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31816c017d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cwikel J, Ilan K, Chudakov B. Women brothel workers and occupational health risks. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(10):809–15. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.10.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terre des hommes, Partnership Nepal. A study on the ‘destination side’ of the trafficking of Nepalese girls to India. [Accessed June 10, 2009]; Available at: www.un.org.np/reports/TDS/2004/TDS-Traffikking-of-Nepali-Girls-to-India_04.pdf.

- 24.Rushing R, Watts C, Rushing S. Living the reality of forced sex work: perspectives from young migrant women sex workers in northern Vietnam. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2005;50(4):e41–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gayen S, Chowdhury D, Saha N, Debnath R. Bangkok Durbar’s (DMSC) position on trafficking and the formation of Self Regulatory Board. International Conference on AIDS; Bangkok, Thailand. 2004. [Google Scholar]