Abstract

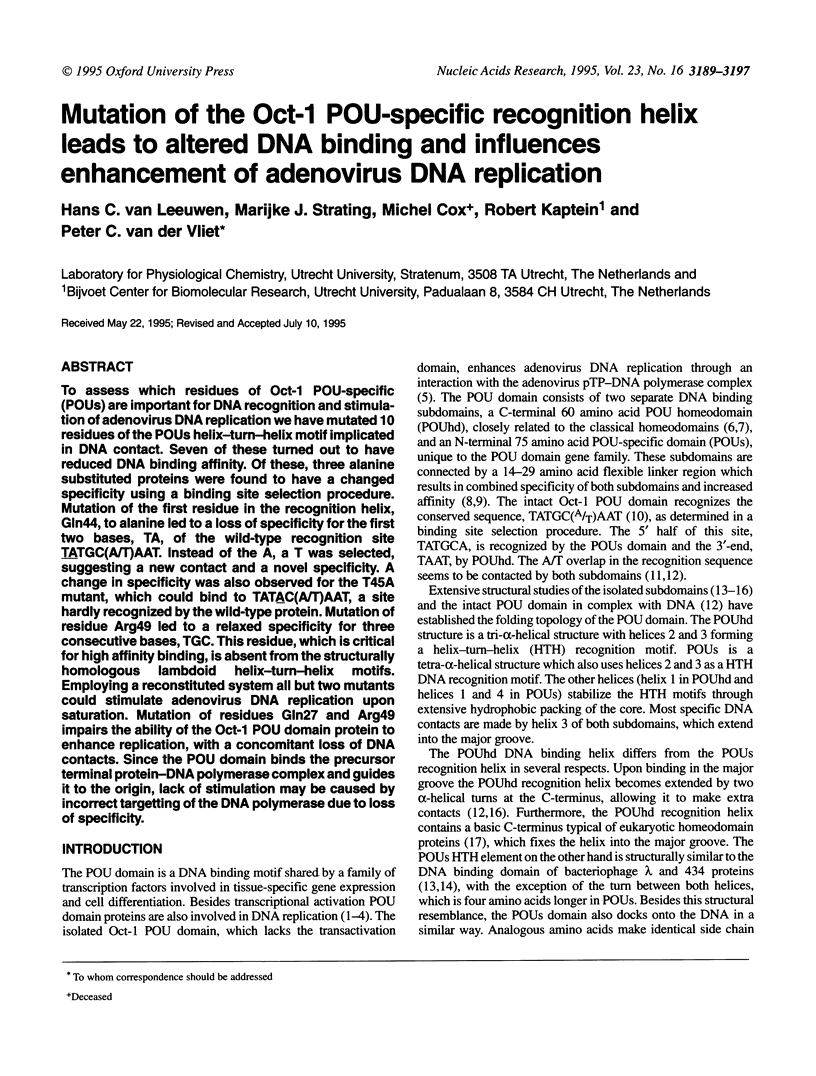

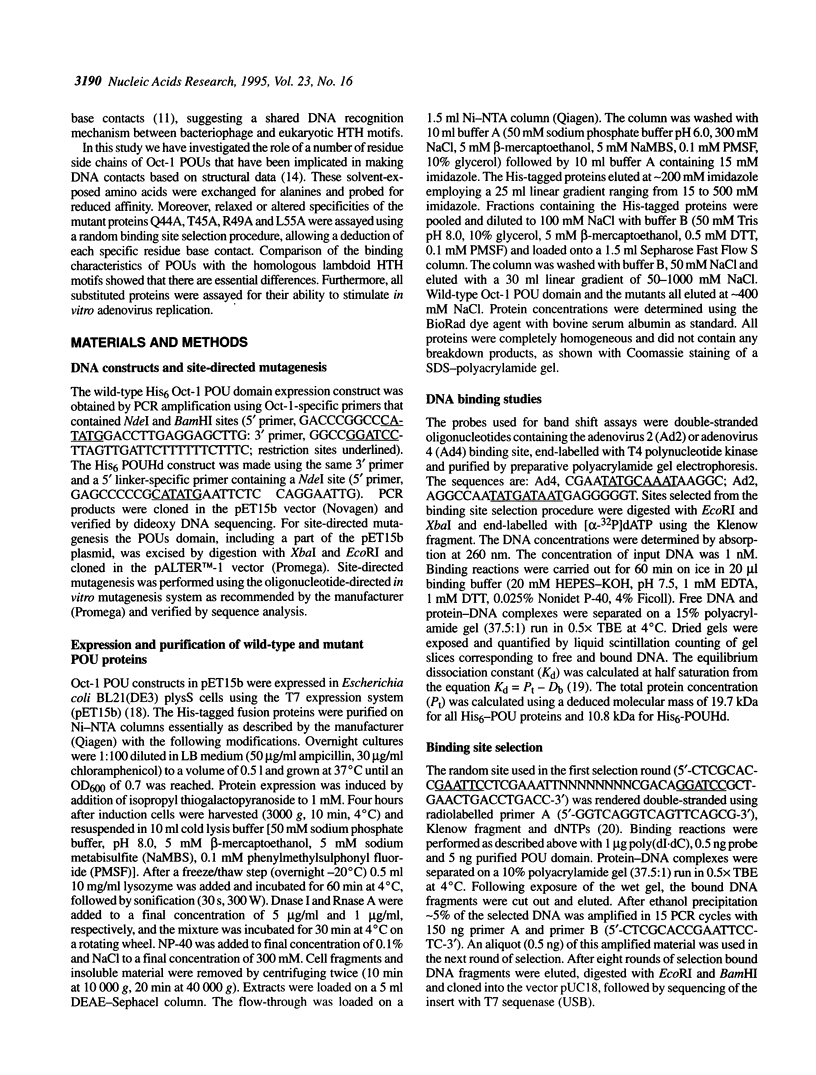

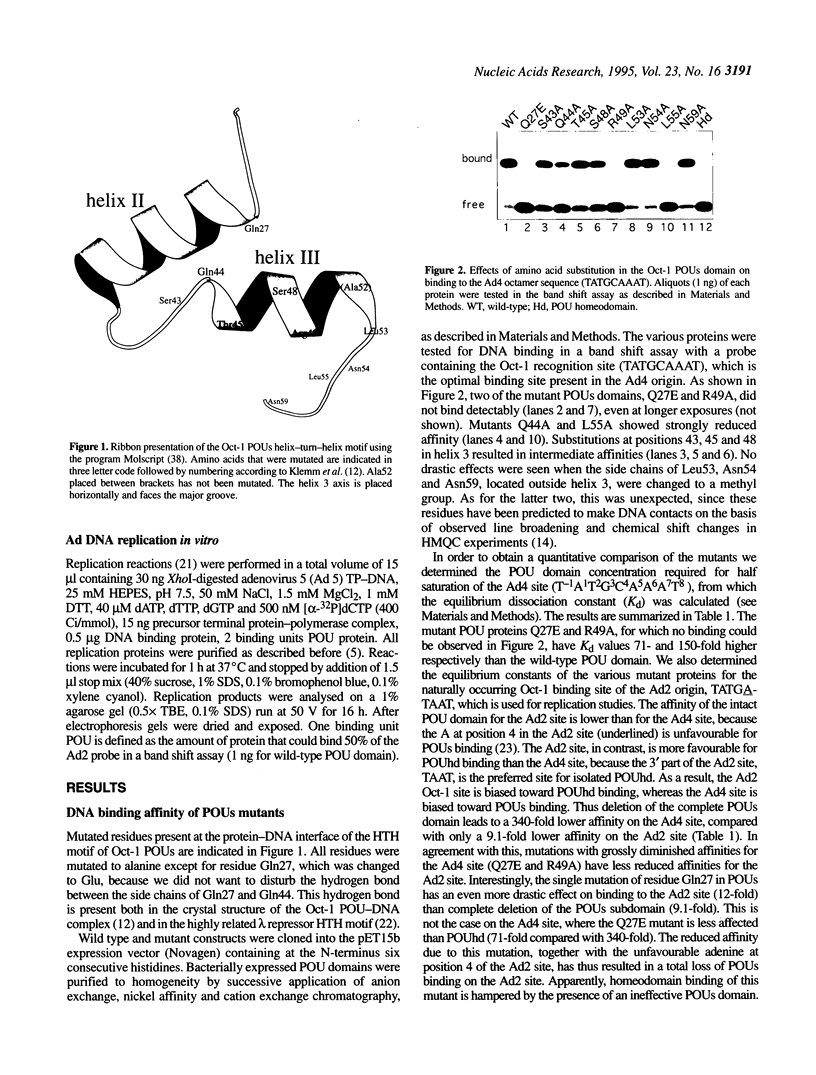

To assess which residues of Oct-1 POU-specific (POUs) are important for DNA recognition and stimulation of adenovirus DNA replication we have mutated 10 residues of the POUs helix-turn-helix motif implicated in DNA contact. Seven of these turned out to have reduced DNA binding affinity. Of these, three alanine substituted proteins were found to have a changed specificity using a binding site selection procedure. Mutation of the first residue in the recognition helix, Gln44, to alanine led to a loss of specificity for the first two bases, TA, of the wild-type recognition site TATGC(A/T)AAT. Instead of the A, a T was selected, suggesting a new contact and a novel specificity. A change in specificity was also observed for the T45A mutant, which could bind to TATAC(A/T)AAT, a site hardly recognized by the wild-type protein. Mutation of residue Arg49 led to a relaxed specificity for three consecutive bases, TGC. This residue, which is critical for high affinity binding, is absent from the structurally homologous lambdoid helix-turn-helix motifs. Employing a reconstituted system all but two mutants could stimulate adenovirus DNA replication upon saturation. Mutation of residues Gln27 and Arg49 impairs the ability of the Oct-1 POU domain protein to enhance replication, with a concomitant loss of DNA contacts. Since the POU domain binds the precursor terminal protein-DNA polymerase complex and guides it to the origin, lack of stimulation may be caused by incorrect targetting of the DNA polymerase due to loss of specificity.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aggarwal A. K., Rodgers D. W., Drottar M., Ptashne M., Harrison S. C. Recognition of a DNA operator by the repressor of phage 434: a view at high resolution. Science. 1988 Nov 11;242(4880):899–907. doi: 10.1126/science.3187531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assa-Munt N., Mortishire-Smith R. J., Aurora R., Herr W., Wright P. E. The solution structure of the Oct-1 POU-specific domain reveals a striking similarity to the bacteriophage lambda repressor DNA-binding domain. Cell. 1993 Apr 9;73(1):193–205. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90171-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beamer L. J., Pabo C. O. Refined 1.8 A crystal structure of the lambda repressor-operator complex. J Mol Biol. 1992 Sep 5;227(1):177–196. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90690-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bork P., Doolittle R. F. Proposed acquisition of an animal protein domain by bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Oct 1;89(19):8990–8994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.8990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botfield M. C., Weiss M. A. Bipartite DNA recognition by the human Oct-2 POU domain: POUs-specific phosphate contacts are analogous to those of bacteriophage lambda repressor. Biochemistry. 1994 Mar 8;33(9):2349–2355. doi: 10.1021/bi00175a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuprina V. P., Rullmann J. A., Lamerichs R. M., van Boom J. H., Boelens R., Kaptein R. Structure of the complex of lac repressor headpiece and an 11 base-pair half-operator determined by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and restrained molecular dynamics. J Mol Biol. 1993 Nov 20;234(2):446–462. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coenjaerts F. E., van Oosterhout J. A., van der Vliet P. C. The Oct-1 POU domain stimulates adenovirus DNA replication by a direct interaction between the viral precursor terminal protein-DNA polymerase complex and the POU homeodomain. EMBO J. 1994 Nov 15;13(22):5401–5409. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06875.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker N., Cox M., Boelens R., Verrijzer C. P., van der Vliet P. C., Kaptein R. Solution structure of the POU-specific DNA-binding domain of Oct-1. Nature. 1993 Apr 29;362(6423):852–855. doi: 10.1038/362852a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring W. J., Affolter M., Bürglin T. Homeodomain proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:487–526. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.002415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S., O'Hare P. Mapping of a major surface-exposed site in herpes simplex virus protein Vmw65 to a region of direct interaction in a transcription complex assembly. J Virol. 1993 Feb;67(2):852–862. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.852-862.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild A., Ptashne M. Homologous interactions of lambda repressor and lambda Cro with the lambda operator. Cell. 1986 Mar 28;44(6):925–933. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingraham H. A., Flynn S. E., Voss J. W., Albert V. R., Kapiloff M. S., Wilson L., Rosenfeld M. G. The POU-specific domain of Pit-1 is essential for sequence-specific, high affinity DNA binding and DNA-dependent Pit-1-Pit-1 interactions. Cell. 1990 Jun 15;61(6):1021–1033. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90067-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jancso A., Botfield M. C., Sowers L. C., Weiss M. A. An altered-specificity mutation in a human POU domain demonstrates functional analogy between the POU-specific subdomain and phage lambda repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Apr 26;91(9):3887–3891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan S. R., Pabo C. O. Structure of the lambda complex at 2.5 A resolution: details of the repressor-operator interactions. Science. 1988 Nov 11;242(4880):893–899. doi: 10.1126/science.3187530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemm J. D., Rould M. A., Aurora R., Herr W., Pabo C. O. Crystal structure of the Oct-1 POU domain bound to an octamer site: DNA recognition with tethered DNA-binding modules. Cell. 1994 Apr 8;77(1):21–32. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J. S., Cleary M. A., Herr W. A single amino acid exchange transfers VP16-induced positive control from the Oct-1 to the Oct-2 homeo domain. Genes Dev. 1992 Nov;6(11):2058–2065. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.11.2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., He X., Gerrero M. R., Mok M., Aggarwal A., Rosenfeld M. G. Spacing and orientation of bipartite DNA-binding motifs as potential functional determinants for POU domain factors. Genes Dev. 1993 Dec;7(12B):2483–2496. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita E. H., Shirakawa M., Hayashi F., Imagawa M., Kyogoku Y. Secondary structure of the oct-3 POU homeodomain as determined by 1H-15N NMR spectroscopy. FEBS Lett. 1993 Apr 26;321(2-3):107–110. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80088-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock R., Treisman R. A sensitive method for the determination of protein-DNA binding specificities. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990 Nov 11;18(21):6197–6204. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.21.6197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz J. L., Kristie T. M., Sharp P. A. Recognition of the surface of a homeo domain protein. Genes Dev. 1992 Nov;6(11):2047–2057. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.11.2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld M. G. POU-domain transcription factors: pou-er-ful developmental regulators. Genes Dev. 1991 Jun;5(6):897–907. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.6.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher M. A., Choi K. Y., Zalkin H., Brennan R. G. Crystal structure of LacI member, PurR, bound to DNA: minor groove binding by alpha helices. Science. 1994 Nov 4;266(5186):763–770. doi: 10.1126/science.7973627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaraja M., Botfield M. C., Mueller M., Jancso A., Weiss M. A. Solution structure of a POU-specific homeodomain: 3D-NMR studies of human B-cell transcription factor Oct-2. Biochemistry. 1994 Aug 23;33(33):9845–9855. doi: 10.1021/bi00199a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studier F. W., Rosenberg A. H., Dunn J. J., Dubendorff J. W. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:60–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm R. A., Das G., Herr W. The ubiquitous octamer-binding protein Oct-1 contains a POU domain with a homeo box subdomain. Genes Dev. 1988 Dec;2(12A):1582–1599. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.12a.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M. A framework for the DNA-protein recognition code of the probe helix in transcription factors: the chemical and stereochemical rules. Structure. 1994 Apr 15;2(4):317–326. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M. Common features in DNA recognition helices of eukaryotic transcription factors. EMBO J. 1993 Aug;12(8):3221–3226. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05991.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrijzer C. P., Alkema M. J., van Weperen W. W., Van Leeuwen H. C., Strating M. J., van der Vliet P. C. The DNA binding specificity of the bipartite POU domain and its subdomains. EMBO J. 1992 Dec;11(13):4993–5003. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrijzer C. P., Kal A. J., Van der Vliet P. C. The DNA binding domain (POU domain) of transcription factor oct-1 suffices for stimulation of DNA replication. EMBO J. 1990 Jun;9(6):1883–1888. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08314.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrijzer C. P., Kal A. J., van der Vliet P. C. The oct-1 homeo domain contacts only part of the octamer sequence and full oct-1 DNA-binding activity requires the POU-specific domain. Genes Dev. 1990 Nov;4(11):1964–1974. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.11.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrijzer C. P., Van der Vliet P. C. POU domain transcription factors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993 Apr 29;1173(1):1–21. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(93)90237-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrijzer C. P., van Oosterhout J. A., van Weperen W. W., van der Vliet P. C. POU proteins bend DNA via the POU-specific domain. EMBO J. 1991 Oct;10(10):3007–3014. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07851.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker S., Hayes S., O'Hare P. Site-specific conformational alteration of the Oct-1 POU domain-DNA complex as the basis for differential recognition by Vmw65 (VP16). Cell. 1994 Dec 2;79(5):841–852. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegner M., Drolet D. W., Rosenfeld M. G. POU-domain proteins: structure and function of developmental regulators. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1993 Jun;5(3):488–498. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90015-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weickert M. J., Adhya S. A family of bacterial regulators homologous to Gal and Lac repressors. J Biol Chem. 1992 Aug 5;267(22):15869–15874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharton R. P., Ptashne M. A new-specificity mutant of 434 repressor that defines an amino acid-base pair contact. 1987 Apr 30-May 6Nature. 326(6116):888–891. doi: 10.1038/326888a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]