Abstract

Stigma, lack of knowledge, and misconceptions about depression are considered pervasive barriers contributing to the disparities Latino adults with limited English proficiency (LEP) face in accessing and receiving high quality depression care. The development of culturally and linguistically appropriate health literacy tools, such as fotonovelas, can help address these barriers to depression care in the Latino community. Fotonovelas are booklets that use posed photographs with simple text bubbles to portray soap opera stories that convey educational messages. The aim of this manuscript is to describe the development of a depression fotonovela adapted for Latinos with LEP. We present the conceptual model that informed this depression literacy tool and illustrate how findings from several studies were used to identify educational messages. Our production process delineates practical steps of how to use a multi-stakeholder approach to develop a health-related fotonovela. Implications for practice of this innovative depression literacy tool are discussed.

Keywords: Depression, Latinos, Fotonovelas

Introduction

Compared to Whites with similar mental health needs, Latinos with limited English proficiency (LEP) are more likely to underutilize mental health services, drop out of care, and receive care that is poor in quality (USDHHS, 2001). Stigma, low health literacy, misconceptions about treatments, and lack of knowledge about depression are considered pervasive barriers deterring Latinos with LEP from seeking and receiving timely depression care (USDHHS, 2001). The Institute of Medicine (2004) estimates that more than 1 in 4 Latinos live in linguistically isolated households where no one over the age of 14 speaks English “very well.” This segment of the Latino population faces considerable barriers in locating basic health information, navigating the health care system, and following clinicians’ recommendations (Lewis-Fernandez, Das, Alfonso, Weissman, & Olfson 2005).

To date, few standardized patient education programs and tools for depression exist for Latinos with LEP. Depression literacy tools that are linguistically and culturally adapted for LEP populations that present mental health information in familiar, readable, and entertaining formats and can activate individuals to take appropriate action in times of need are needed to reduce disparities in mental health care. The goal of this manuscript is to describe the development of a depression fotonovela adapted for Latinos with LEP. Health-related fotonovelas use posed photographs with simple text bubbles to portray soap opera style stories that convey educational messages.

Fotonovela as a depression literacy tool

Health literacy is “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” (IOM, 2004, p. 2). Health literacy levels are lower among older adults, racial and ethnic minorities, individuals with limited education, the poor, and those with LEP (IOM, 2004). Low health literacy is related to poor management of chronic diseases, lack of basic knowledge about medical conditions and treatments, less understanding and use of preventive services, worse health outcomes, and higher rates of hospitalization and emergency care use (IOM, 2004). Given the negative effects of low health literacy and the fact that individual-level factors, such as knowledge, attitudes, and stigma influence the recognition of depression and use of professional services among Latinos with LEP, we surmise that depression literacy tools that are culturally and linguistically adapted provide a viable intervention to counteract individual level barriers to depression care.

Fotonovelas are a popular format that has been used with low literate populations for a variety of purposes (e.g., AIDS education, tuberculosis treatment; Cabrera et al., 2002). Different advocacy organizations (e.g., American Red Cross, National Alzheimer’s Association) have used fotonovelas as an educational tool to reach different Latino communities (Valle, Yamada, & Matiella, 2006). Health-related fotonovelas differ from common patient education materials, such as brochures and informational pamphlets, in that they incorporate popular images, cultural norms, simple text, dramatic stories, and vivid pictures to engage Latino audiences and raise their awareness about health issues, health promotion, and combat stigma. The uniqueness of fotonovelas as a culturally informed health literacy tool is that it embeds engaging visual elements and educational messages within the context of an entertaining dramatic story that portrays characters in common everyday situations that the targeted audience can identify with. The aim of this manuscript is to describe the development of a theoretically informed depression fotonovela adapted for Latinos with LEP. We first present the conceptual model that informed this depression literacy tool. We then illustrate how findings from several studies were used to inform the story line development and educational messages. Lastly, we present the multi-stakeholder approach used to produce the fotonovela.

Conceptual Model

Our fotonovela draws from two health behavior theories and an innovative communication strategy. First, illness perceptions are used to inform the presentation of depressive symptoms and the illness experience surrounding depression. These perceptions are the cognitive and emotional representations that people hold about illnesses and encompass the symptoms, causes, and consequences attributed to an illness, their expectations about the course of the illness (e.g., acute or chronic) and whether it can be controlled with treatment and/or personal efficacy (Leventhal, Deifenbach, & Leventhal, 1992). Illness perceptions are influenced by individuals’ social and cultural environment and are a core component of the self-regulatory model of illness cognition (Cameron & Leventhal, 2003). Individuals’ perceptions of depression are related to outcomes associated with mental health care disparities, such as service use, medication adherence, coping strategies, intentions to seek care, treatment preferences, and functioning (Brown et al., 2007; Cabassa & Zayas, 2007).

We used illness perceptions to inform how characters in our fotonovela story experienced depression focusing on their symptoms, the causes and consequences they attributed to their depression, and their beliefs about depression treatments and self-efficacy. We used these experiences to introduce and reiterate the following adaptive illness perceptions and help-seeking behaviors: (1) depression is a real, common, and serious medical condition that is composed of key symptoms that impact a person’s functioning; (2) depression can be treated; and (3) when talking with your doctor disclose all your symptoms and use the word depression. Our goal was to develop an engaging story that validated the communities’ perceptions and concerns of depression, provided appropriate help-seeking behavior models, and presented information about depression. We targeted symptom recognition in order to counteract disparities in seeking mental care associated with not identifying depression as a treatable medical condition. Recognition of need is usually the first step in seeking mental health care and has been found to be a strong predictor of service use (Mojtabai, Olfson, & Mechanic, 2002). We stressed the use of the word depression when seeking professional help as past studies have found that when individuals use the label of depression their doctors are more likely to diagnose depression and initiate treatment (Hickie et al., 2001).

Second, we used the theory of reasoned action to target individuals’ attitudes toward depression treatments and social norms associated with seeking professional help (Ajzen, 1991). Attitudes toward depression treatments include individuals’ understanding, knowledge and evaluation of depression care. We used several strategies to counteract prevalent views in the Latino community that antidepressant medications are addictive and harmful and the stigma surrounding taking medications and visiting a counselor. First, authority figures (e.g., primary care doctors) were used to present factual information about the benefits of antidepressants, their side effects, and appropriate use, stressing adherence to medications and open communication with medical professionals. Second, main characters modeled common concerns about these medications and how they overcame these concerns by talking with their doctors, pharmacists, and friends. Third, we presented a character that had negative experiences because of delays in seeking care. Lastly, we presented characters that had positive experiences with medications and counseling.

Social norms refer to the social expectations or pressures to perform particular health behaviors and the individual’s motivation to comply with these expectations (Ajzen, 1991). Among Latino groups, family members and friends are commonly consulted in combination with formal health and mental health services to cope with mental health problems (Cabassa & Zayas, 2007). The story depicted in our fotonovela exemplifies the saliency social norms have in the recognition of depression and help-seeking process by having our main character consult friends and family members about her situation and receive advice and information about her symptoms and how to seek professional help. This approach enabled us to provide concrete examples of how friends and family members can help a loved one with depression. Our story also challenged common maladaptive social norms (e.g., depression is a sign of weakness) prevalent in the Latino community. We hypothesize that our fotonovela can decrease misconceptions about depression treatments, increase intentions to seek professional help, and increase skills to help someone with depression.

The Entertainment-Education (E-E) communication strategy which consists of incorporating educational message into popular entertainment content (e.g., print media) to increase knowledge, create favorable attitudes, shift social norms, and motivate people to take socially responsible actions informed the development of our fotonovela. (Singhal & Rogers, 1999). E-E relies upon the social modeling concept drawn from social learning theory to increase self-efficacy - the belief that individuals can control specific outcomes in their lives (Bandura, 2004). E-E stipulates that dramatic narratives are more effective than traditional persuasive messages (e.g., patient education brochures) in changing attitudes and motivating behavior change by creating homiphily - that is, engaging individuals at an emotional and cognitive level through the use of characters and stories that are perceived as similar to the audience’s everyday experiences (Borrayo 2004). E-E narratives incorporate consciousness raising and dramatic relief - two common behavior change processes used to help individuals move through the stages of behavior change (Prochaska, Redding & Evers, 2002).

We used E-E to develop characters, visuals, and a story line that our targeted audience could relate to and present positive and negative behavior models. The goal was to enhance audience identification in order for readers to form a personal connection with the characters and their circumstances. Audience involvement in E-E programs is linked to increases in self-efficacy and interpersonal communications about the information presented in the program, two important precursors for behavioral change (Sood, 2002). The combination of attractive visuals and easy to understand text is considered an effective strategy in patient education interventions (Noar, Benac, & Harris, 2007). Developing a narrative that enhances homiphily and audience involvement is an important anti-stigma strategy as past studies have shown that personal contact with an individual suffering from a mental illness either in person or via media can be a useful intervention to increase knowledge about mental illness and reduce stigma (Reinke et al., 2004).

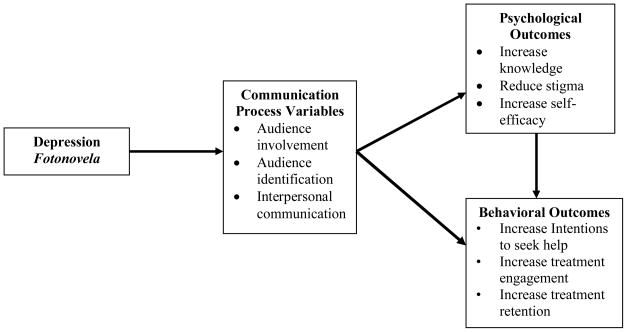

The use of these behavioral theories and communication strategies enabled us to develop a conceptual model (See Figure 1) specifying how our fotonovela influences psychological (e.g., knowledge, symptom recognition) and behavioral (e.g., behavioral intentions, treatment engagement) outcomes. We hypothesize that the effect that our fotonovela has on these outcomes is mediated by three communication process variables derived from the E-E strategy and based on Sood’s (2002) work. First, audience involvement is defined as the degree to which readers relate the fotonovela story to their personal experiences. Second, audience identification is the extent that readers personally identify with the fotonovela characters and other key features of the story, such as places and themes. Lastly, interpersonal communication is defined as the degree that readers share or talk about the information presented in the fotonovela with friends and/or family members (Sood, 2002). We believe that these three process variables serve as a “door-opener” that help readers process new information, challenge maladaptive social norms, and consider new behavioral options (Ritterfesd & Jin, 2006, p. 249). Each of these communication processes sets the stage for attitudinal and behavioral change. The ultimate goal of our fotonovela is to activate Latino community members with the knowledge and skills that will empower them to make informed decisions about how to identify and cope with depression.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model

Studies Informing Depression Fotonovela

We describe in this section how findings from two studies informed the content and story line development of our fotonovela. Both studies recruited low-income, mostly Spanish speaking, immigrant Latino adults receiving services at primary care settings. The first study used a vignette methodology depicting an individual experiencing depression to examine how perceptions of depression, attitudes toward depression treatments, and social norms influenced the help-seeking intentions of 95 Latino immigrants (Cabassa, Lester, & Zayas, 2007). The second study used focus groups and in-depth qualitative interviews to examine the illness perceptions, attitudes toward care and help-seeking behaviors of 19 Spanish-speaking Latino immigrants suffering from depression and diabetes and enrolled in a randomized controlled trial (Cabassa, Hansen, Palinkas, & Ell, 2008). Four key findings from these studies helped us identify depression literacy targets for our fotonovela.

First, results from the first study indicated that increasing recognition of depression among Latinos with LEP is an important mental health literacy target. In this study, 45% of participants were not able to identify the vignette’s subject as a depressed person, particularly among those who scored low in language acculturation (Cabassa et al., 2007). This rating is higher than the 31% of adult respondents who failed to correctly recognize depression in a similar vignette in a nationally representative opinion survey in the U. S. (Link et al., 1999). Recognition of depression was also a predictor of intentions to seek professional depression care (e.g., primary care doctor, mental health specialist) after adjusting for demographic, acculturation and clinical covariates (Cabassa & Zayas, 2007).

Second, both studies found that depression was perceived as a serious condition that (1) blended somatic, anxiety-like, and emotional symptoms that seriously impacted a person’s functioning; and (2) was attributed to the accumulation of interpersonal and social stressors (Cabassa et al., 2007; Cabassa et al., 2008). These findings provided us valuable information of how to describe the cause and consequences of depression as experienced by the main character in our fotonovela and the social circumstances surrounding her condition.

Third, both studies revealed serious apprehensions toward antidepressant medications. In the first study, 61% endorsed the belief that antidepressants are addictive and 38% felt that these medications would make people feel drugged or numbed (Cabassa et al., 2007). Addiction concerns were related to fears of dependency and loss of control that negatively impacted a person’s functioning and quality of life. Qualitative findings indicated that participants viewed antidepressants as harmful and the use of these medications was linked to being labeled as loco (crazy). These negative attitudes were also reported to be prevalent in the Hispanic community and promulgated by Spanish-language media. Furthermore, negative attitudes toward antidepressants were linked to delaying seeking care and adhering to treatment (Hansen et al., 2008).

Lastly, both studies highlighted the prominent role that family members and friends play in help-seeking behaviors for depression. Help-seeking decisions were characterized as a social process in which informal sources of care (e.g., family members) were consulted and if the issue was not resolved then formal sources of care (e.g., doctors) were sought to cope with depression (Cabassa & Zayas, 2007). Support from family members and friends was found to be an important component of helping individuals recognize their need for care and initiate treatment (Hansen et al., 2008) and is linked to intentions to seek professional care (Cabassa & Zayas, 2007). In all, findings from these studies provided us access to local knowledge and helped us identify depression literacy targets for our fotonovela

Fotonovela Production

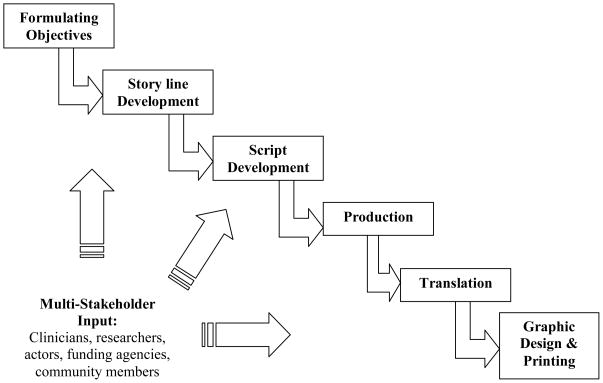

The production consisted of formulating objectives, developing the story line and script, the production process, translating the fotonovela content into Spanish, and graphic design and printing. We assembled a team composed of a pharmacist, a social work researcher, and a fotonovela producer to lead the production process. We also used multi-stakeholder input (e.g., community members, clinicians, professional writers) to inform the development of our fotonovela. Below we summarize the major production steps (See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Production Process

Formulation of objectives

We began by generating a list of key educational messages and behavioral targets to guide our development. The list emerged from past research and review of the literature, discussions at team meetings, and consultations with experienced clinicians and researchers. After several iterations, the following three objectives were formulated: (a) increase knowledge of depressive symptoms and their detrimental effects on a person’s functioning; (b) reduce stigma; and (c) model appropriate help-seeking and adherence behaviors. These objectives guided the story line and script development.

Story line development

The story line was designed to meet two goals: 1) convey educational messages and 2) entertain and engage the reader with a dramatic, soap opera story. The story line consisted of the description of main and supportive characters and the chronological sequence of events. The fotonovela was developed for a specific audience: Latino adult men and women with LEP. We developed characters that resembled the targeted population and could serve as positive role models. The story line evolved through an iterative process in which multiple stakeholders reviewed and provided feedback on our work through meetings and emails. Their comments were then incorporated into the story line.

Script development

Once a consensus between our three team members was reached about the content of the story line, a formal script was written in collaboration with a professional writer. The script was written using language at a 4th grade reading level. Upon completion of the first draft, stakeholders reviewed the script and provided suggestions for revisions. Once revisions were incorporated into the script, a reading of the script conducted by several actors was performed in the presence of the project director, producer, photographer, and stakeholders. The following questions were used to guide the discussion in this meeting: Is the script easy to follow? Are the fotonovela messages clear? Is the story entertaining? Does the story reflect the culture, values, and norms of the targeted audience? Notes from this meeting were used to revise the script. The final script served as a blueprint to guide the production process.

Production

The producer obtained all the necessary permits for filming in different community locations, scheduled production dates and times, hired community actors and a hair/makeup artist, rented digital photographic equipment, chose wardrobe, and assembled the production support team (e.g., production assistant). The director/photographer also sketched each of the fotonovela pages including number and location of frames to help organize and coordinate the shooting of each scene. Photographs were reviewed by the director/photographer and producer during each scene to determine if there was a match between the visual content and text or if modifications were needed. For instance, when a photo did not fit with the text the director/photographer shot a different photo or the producer modified the text to capture the expression or emotion conveyed in the photo. The ultimate goal of this process was for the text and photographs to complement each other in a coherent, visually appealing, and entertaining story.

Translation

Once the English version of the fotonovela text, including the cover, credit page, fotonovela story, and the question and answer (Q & A) page was approved by the three team members, the translation into Spanish was initiated. We used standard backtranslation techniques (Brislin, 1986) to translate the main text of the fotonovela. A decentering approach in which language equivalence is attained by adjusting the wording in both the source (English) and target (Spanish) languages to convey the desired meaning was used to translate the cover, credit and Q & A pages (Rogler, 1999). The English and Spanish versions of the fotonovela were reviewed by bilingual stakeholders. Reviewers identified grammatical errors, areas of discrepancies between the English and Spanish versions, and provided recommendations for alternative words and phrases. Input from reviewers was incorporated into both versions of the fotonovela and approved by the three team members. Both versions of our fotonovela were independently reviewed by the cultural and linguistic review board of one of our funding agencies that specializes in evaluating patient educational materials for low literate populations. This board evaluated the readability level of our materials using the Fry Readability Test (Berland et al., 2001) and concluded that both the English and Spanish versions of the fotonovela were at a 4th grade reading level.

Graphic design and printing

A graphic design artist designed the cover, credits, and Q & A pages and assembled the pages of the fotonovela booklet in collaboration with the director/photographer and producer. A small number of fotonovelas were then printed and reviewed by community members not affiliated with the production process to provide comments regarding the content, style, length, and design of the fotonovela. Their input was incorporated into the final version of the fotonovela.

Discussion

We presented in this manuscript the development of a theoretically informed and empirically grounded depression fotonovela adapted for Latinos with LEP. Concepts from two health behavior theories and entertainment-education strategies were used to develop the theoretical foundations for this depression literacy tool. Findings from several studies and multi-stakeholder input provided us access to local knowledge that helped identify key mental health literacy targets and informed the development of our dramatic story. The production process described steps taken to transform theoretical principles and empirical findings into a fotonovela that conveys health education messages using a visually appealing and entertaining story.

The incorporation of multi-stakeholder input was a major asset for this project. For instance, we consulted several professional groups (e.g., pharmacists, psychiatrist) to review our educational message and provide input about the accuracy of the medical information we incorporated throughout the fotonovela. We used multi-stakeholder input to review the language, idioms, and expressions used to convey educational messages in both English and Spanish. This feedback kept our team grounded to make sure that the fotonovela was entertaining and acceptable to our audience. We used a flexible approach to seek stakeholder input that included having meetings- in person or via telephone- with different groups and asking for feedback on different materials via e-mail. This approach enabled us to accommodate schedules of different individuals and to open our pool of stakeholders to a national level. The incorporation and balancing of the opinions and feedback from different stakeholders was not an easy task. We relied on a centralized group made up of the three team members to discuss stakeholders’ feedback and make project decisions. Having a producer as a team member was a real asset as he was able to translate the different ideas generated from our stakeholders into the fotonovela format and kept us in check as to what was feasible given our limited resources.

Our fotonovela is not without its limitations. The effectiveness of our depression literacy tool remains unknown. The next step is to evaluate whether our fotonovela outperforms standard patient educational materials on knowledge, attitudinal, and behavioral outcomes. The formative research informing our fotonovela included mostly Mexican and Central American immigrant populations from Midwest and West Coast urban regions, and the production was based in East Los Angeles, California. Our tool may not reflect the concerns of other Latino groups. Recent studies, however, have shown that our depression literacy targets are key barriers to depression care among different Latino groups (e.g., Puerto Rican, Cubans; Interian, Martinez, Guarnaccia, Vega, & Escobar, 2007; Pincay & Guarnaccia, 2007). Testing the effectiveness of our fotonovela among different Latino groups and across different acculturation levels will enable us to establish external validity.

Implications

The implications of our fotonovela are multifaceted. This tool could be used to augment existing depression treatments in primary and specialty care settings as a patient education resource. Clinicians could use the fotonovela as an engagement bridge to: (1) educate patients about depression and its treatments, (2) initiate an open dialogue with patients about their concerns and options for care; and (3) activate patients to become involved in their own care. The fotonovela could be used as part of a community mental health literacy program in which communities are informed about depression and its treatments. The fotonovela could be distributed through different media outlets (e.g., newspapers), or adapted into other mediums (e.g., website, radio) for broader dissemination. This approach could be part of a comprehensive educational campaign supported by an information hotline service to help answer the public’s questions and connect at risk individuals to services. Similar approaches have been used for cancer prevention (e.g., Wilkin et al., 2007). Using popular media to disseminate our fotonovela may be an effective means to reach our targeted audience as studies have found that Latinos tend to obtain the majority of their health information from television, radio or newspapers (Livingston, Minushkin, & Cohn, 2008). All of these applications need to be carefully evaluated using rigorous methodologies (e.g., randomized controlled trials).

Depression literacy tools that are linguistically and culturally adapted for Latinos with LEP are needed to target individual level factors linked to disparities in access and quality of care. There is a growing body of research indicating that lack of knowledge, negative attitudes toward treatments, communication problems, and stigma are major barriers that deter Latinos from seeking and engaging in formal mental health care (USDHHS, 2001). Few culturally adapted approaches, however, have been developed that target these individual level factors in the Latino population. Advocacy organizations (e.g., National Alliance for the Mentally Ill), federal, state, and local agencies have developed patient educational materials and curriculums for the Latino community but few have been evaluated and their benefits to reduce disparities in mental health care are still unknown. Future studies are needed to test the effectiveness of our depression fotonovela in combating inequalities in depression care by increasing Latinos’ knowledge and recognition of depressive symptoms, reducing stigma, and encouraging those in need to seek appropriate mental health care.

Contributor Information

Leopoldo J. Cabassa, Email: cabassa@pi.cpmc.columbia.edu, Assistant Director of the New York State Center of Excellence for Cultural Competence at the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Assistant Professor of Clinical Psychiatric Social Work (in Psychiatry), at the Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, NY

Gregory B. Molina, Email: gbm@usc.edu, Project Manager at the University of Southern California School of Pharmacy, Los Angeles, California, Los Angeles, CA

Melvin Baron, Email: mbaron@usc.edu, Associate Professor at the University of Southern California School of Pharmacy, Los Angeles, CA

References

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health, Education and Behavior. 2004;31:143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berland GK, Elliott MN, Morales LS, Algazy JI, Kravitz RL, Broder MS, et al. Health information on the internet: Accessibility, quality, and readability in English and Spanish. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285(20):2612–2621. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.20.2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrayo EA. Where’s Maria? A video to increase awareness about breast cancer and mamography screening among low-literacy Latinas. Preventive Medicine. 2004;39:99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brislin RW. The wording and translation of research instruments. In: Loner WJ, Berry JW, editors. Field methods in cross-cultural research. Beverly Hills: SAGE; 1986. pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, Battista DR, Sereika SM, Bruehlman RD, Dunbar-Jacob J, Thase ME. Primary care patients’ personal illness models for depression: Relationship to coping behavior and functional disability. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2007;29(6):492–500. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa LJ, Hansen MC, Palinkas LA, Ell K. Azúcar y nervios: Explanatory models and treatment experiences of Hispanics with diabetes and depression. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66(12):2413–2424. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa LJ, Lester R, Zayas LH. “It’s like being in a labyrinth:” Hispanic immigrants’ perceptions of depression and attitudes toward treatments. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2007;9:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9010-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa LJ, Zayas LH. Latino immigrants’ intentions to seek depression care. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77(2):231–242. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera DM, Morisky DE, Chin S. Development of a tuberculosis education booklet for Latino immigrant patients. Patient Education and Counseling. 2002;46:117–124. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron LD, Leventhal H, editors. The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour. London: Routledge; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Copper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, Rost KM, Meredith LS, Rubenstein LV, Wang NY, Ford DE. The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic and White primary care patients. Medical Care. 2003;41(4):479–489. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000053228.58042.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen MC, Cabassa LJ, Palinkas LA, Ell K. Unpublished Manuscript. 2008. Pathways to depression care: Help-seeking experience of low-income Latinos with diabetes and depression. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickie IB, Davenport TA, Scott EM, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Naismith SL, Koschera A. Unmet need for recognition of common mental disorders in Australian general practice. Medical Journal of Autsralia. 2001;175(Suppl):S18–24. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Health literacy: A prescription to end confusion. Washington, D. C: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interian A, Martinez IE, Guarnaccia PJ, Vega WA, Escobar JI. A Qualitative analysis of the perception of stigma among Latinos receiving antidepressants. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(12):1591–1594. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.12.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal A, Deifenbach M, Leventhal EA. Illness cognition: Using common sense to understand adherence and affect cognition interactions. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1992;16:143–163. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Fernandez R, Das AK, Alfonso C, Weissman MM, Olfson M. Depression in US Hispanics: Diagnostic and management considerations in family practice. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 2005;18(4):282–296. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.4.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, Stueve A, Pescosolido BA. Public conceptions of mental illness: Labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(9):1328–1333. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston G, Minushkin S, Cohn D. Hispanics and health care in the United States: Access, information and knowledge. A joint Pew Hispanic Center and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Research Report. 2008 Retrieved November 18, 2008 from http://pewhispanic.org/files/reports/91.pdf.

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Mechanic D. Perceived need and help-seeking in adults with mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59(1):77–84. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133(4):673–693. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pincay IEM, Guarnaccia PJ. “It’s like going through an earthquake”: Anthropological perspectives on depression among Latino immigrants. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2007;9:17–28. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Redding CA, Evers KE. The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, research and practice. California: Jossey Bass; 2002. pp. 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Reinke RR, Corrigan PW, Leonhard C, Lundin RK, Kubiak MA. Examining two aspects of contact on the stigma of mental illness. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2004;3:377–389. [Google Scholar]

- Ritterfeld U, Jin S. Addressing media stigma for people experiencing mental illness using an entertainment-education strategy. Journal of Health Psychology. 2006;11(12):247–267. doi: 10.1177/1359105306061185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogler LH. Implementing cultural sensitivity in mental health research: Convergence and new directions. Psychline. 1999;3:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal A, Rogers E. Entertainment-Education: A Communication Strategy for Social Change. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sood S. Audience involvement and entertainment-educations. Communication Theory. 2002;12(2):153–172. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A supplement to mental health: A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U. S Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valle R, Yamada AM, Matiella AC. Health literacy tool for educating Latino older adults about dementia. Clinical Gerontologist. 2006;30:71–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkin HA, Valente TW, Murphy S, Cody MJ, Huang G, Beck V. Does entertainment-education work with Latinos in the United States? Identification and the effects of a telenovela breast cancer story line. Journal of Health Communication. 2007;12(5):455–469. doi: 10.1080/10810730701438690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]