Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of our study was to determine the prevalence, focus, time commitment, graduation requirements and programme evaluation methods of medical education fellowships throughout the United States. Medical education fellowships are defined as a single cohort of medical teaching faculty who participate in an extended faculty development programme.

Methods

A 26-item online questionnaire was distributed to all US medical schools (n=127) in 2005 and 2006. The questionnaire asked each school if it had a medical education fellowship and the characteristics of the fellowship programme.

Results

Almost half (n=55) of the participating schools (n=120, response rate 94.5 %) reported having fellowships. Duration (10–584 hours) and length (<1 month–48 months) varied; most focused on teaching skills, scholarly dissemination and curriculum design, and required the completion of a scholarly project. A majority collected participant satisfaction; few used other programme evaluation strategies.

Conclusions

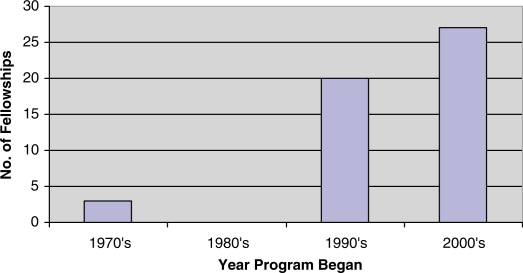

The number of medical education fellowships increased rapidly during the 1990s and 2000s. Across the US, programmes are similar in participant characteristics and curricular focus but unique in completion requirements. Fellowships collect limited programme evaluation data, indicating a need for better outcome data. These results provide benchmark data for those implementing or revising existing medical education fellowships.

Keywords: faculty development, medical faculty, medical education

Many medical schools and hospitals sponsor workshops or seminars to develop and enhance important educational skills of faculty members (1). Competency in teaching, educational scholarship and educational leadership is vital to those involved in the education of not only medical students, residents and fellows, but also colleagues and patients (2). To meet the demands of the doctor shortage, medical schools have increased their enrolment and new schools have been developed (3), thus the need for trained medical educators and physicians is imperative (4).

A medical education fellowship has been defined as a single cohort of medical teaching faculty who participate in a set of extended faculty development activities (3). Medical education fellowships help educators improve their skills and become part of a cadre of educational leaders who can work interdepartmentally and improve education at their institution (5). Strong educational leaders are needed to implement and support change (6), and some fellowships have been created specifically to develop educational leaders from the institution's own educational faculty (7–9).

In medical education fellowships, physicians learn how to adapt their clinical skills set to the educational arena. Hatem (1) proposed that teaching and doctoring utilize a similar skill set, such as eliciting a learner's/patient's needs, setting an agenda, using diagnostic approaches to identify problems, relying on feedback and communication, and evaluating outcomes.

While many suggest that medical education fellowships can have a positive impact on medical schools, little is known about the number of programmes nationally, nor their focus and requirements. The purpose of our study was to determine the prevalence, focus, time commitment, graduation requirements and programme evaluation methods of medical education fellowships throughout the United States.

Methods

We developed a 26-item questionnaire that asked participants to report on the characteristics of their medical education fellowships, such as eligible participants, graduation requirements, length and frequency of the programme, sponsor of the programme, methods of evaluation, degrees associated with the programme and number of graduates. From a list of topics (see Table 2), participants were asked to indicate the extent to which each topic was primary, secondary, tertiary or not a programme focus. An open-ended question asked participants to indicate any additional focus areas or topics not listed on the questionnaire. Respondents were asked to identify all the requirements, evaluation methods and eligible participants of their programme from a list of options, and given the opportunity to identify other items. They were also asked to select the primary sponsor of the fellowship, meeting frequency and whether the fellowship also provided university credit/degree or certificate. To gather information on the duration and number of graduates, participants were asked to fill in the specific numer.

Table 2.

Primary foci, required products of fellows and programme evaluation strategies of medical education fellowships across the USA (n=55)

| No. (%) | |

|---|---|

| Primary focus* | |

| Teaching skills | 43 (78.2) |

| Scholarly dissemination | 32 (58.2) |

| Curriculum design | 29 (52.7) |

| Educational theory | 26 (47.3) |

| Educational research methods | 26 (47.3) |

| Networking with other faculty | 25 (45.5) |

| Educational leadership | 24 (43.6) |

| Programme evaluation | 23 (41.8) |

| Use of educational literature | 22 (40.0) |

| Evaluation of learners | 21 (38.2) |

| Career advancement | 21 (38.2) |

| Reflective practice | 14 ( 25.5) |

| Required products of fellows** | |

| Completion of scholarly project | 44 (80.0) |

| Presentation/publication of scholarly project | 36 (65.5) |

| Design of a curriculum | 24 (43.6) |

| Entries into a journal (i.e., reflective writing) | 14 (25.5) |

| Creation of a career development plan | 13 (23.6) |

| Development of a learning contract | 10 (18.2) |

| Implementation of a curriculum | 10 (18.2) |

| Presentation of a grand rounds session | 4 (7.3) |

| Evaluation methods** | |

| Satisfaction questionnaires | 48 (87.3) |

| Self-assessment questionnaires | 32 (58.2) |

| Follow-up interviews | 31 (56.4) |

| Number of educational activities begun or led by participant | 24 (43.6) |

| Type of educational activity in which participant is involved | 24 (43.6) |

| Direct peer observation/evaluation of participant | 20 (36.4) |

| Curriculum vitae content analysis | 20 (36.4) |

| Course/clerkship/seminar evaluations of participants | 12 (21.8) |

| Portfolios | 12 (21.8) |

Percentage of participants choosing “primary focus”.

Totals equal more than 100% because participants could select more than one choice.

A link to the online questionnaire was sent via e-mail in November 2005, and again in 2006 to allow schools to update their data or respond for the first time. The questionnaire was sent to one medical education contact at each of 127 US medical schools from a list provided by the Association of American Medical Colleges. Instructions directed the contact to have the individual who was most knowledgeable about the faculty development programme complete the questionnaire. Follow-up reminders were sent one and two months later. During the first administration, 72 schools completed the survey. During the second administration, an additional 48 schools completed and 33 schools updated their information. In 2009 we updated information on only the total number of fellows who had graduated from each programme, via phone or e-mail.

Questionnaire data were analysed using descriptive statistics via SPSS 16.0. Where a participant indicated a range, we used the midpoint of the range for our analysis. Approval from the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board was obtained prior to beginning the study.

Results

At the end of 2006, 120 of 127 US medical schools (94.5 %) completed the questionnaire. Almost half of the responding medical schools reported having an educational fellowship (n=55, 45.8 %). Three fellowships were started in the 1970s, none in the 1980s, 20 in the 1990s and 27 in the 2000s, with five schools not responding to the question (Fig. 1). Additionally, 11 schools indicated that they were “considering” or “planning” beginning a programme.

Fig. 1.

Number of medical education fellowships established in the USA by decade.

Most of the 55 programmes were sponsored by the medical school (76.4 %) and 20.0 percent by individual departments, with the remainder sponsored by an endowment or grant (see Table 1). Twelve programmes offered some type of university credit, formal certificate or degree. All fellowships were open to clinical faculty; most were open to basic sciences faculty; and less than 50 percent were open to residents/fellows, nursing, dentistry, public health and other faculty, such as allied health and pharmacy (Table 1). Collectively, the fellowships had graduated over 5,465 fellows, with four schools not responding to this question or just beginning.

Table 1.

Characteristics of medical education fellowship programmes across the USA

| Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Eligible participants* (n=55) | |

| Clinical faculty | 55 (100.0) |

| Basic science faculty | 45 (81.8) |

| Residents or fellows | 22 (40.0) |

| Nursing faculty | 20 (36.4) |

| Dentistry faculty | 19 (34.5) |

| Public health faculty | 15 (27.3) |

| Other (i.e., allied health, pharmacy) | 28 (50.9) |

| Program sponsor (n=55) | |

| Medical school/university | 42 (76.4) |

| Department | 11 (20.0) |

| Endowment or grant funding | 2 (3.6) |

| Meeting frequency (n=54)** | |

| Weekly | 23 (42.6) |

| Bi-weekly | 12 (22.2) |

| Monthly | 16 (29.6) |

| Quarterly | 1 (1.9) |

| Web-based | 2 (3.7) |

| University credit, formal certificate, degree offered (n=55) | 12 (21.8) |

Totals equal more than 100% because participants could select more than one choice.

Missing data from one fellowship.

The median number of contact hours per fellowship programme was 64, ranging from ten to 584 hours. The median duration of each programme was 10.5 months, with a range of less than one month to 48 months. The majority of programmes met either weekly or bi-weekly, with less than a third meeting monthly and less than 5 percent meeting quarterly or online/web-based (Table 1).

Topics reported as a primary focus by 50 percent or more of the programmes included teaching skills, scholarly dissemination and curriculum design. Only about a third or less had a primary focus of evaluation of learners, career advancement or reflective practice (Table 2).

Over half of the programmes required fellows to complete and present or publish a scholarly project. Few (25 percent or less) required fellows to write a journal (reflective writing), create a career development plan, develop a learning contract, implement a curriculum or present educational topics at grand rounds sessions (Table 2).

To evaluate the fellowship programme, almost 90 percent collected fellows' satisfaction about the overall programme and/or individual sessions, with little more than half evaluating the programme through self-assessment questionnaires or follow-up interviews. Less than half reported other strategies, such as peer observation or evaluation, curriculum vitae review or any increase in quantity or type of educational activities with which graduates were involved. Less than a quarter reported using learner evaluations of participants or portfolios (Table 2).

Discussion

Our results indicate an increasing interest in medical education fellowships, especially in the 1990s and 2000s. We suggest this interest is in response to many of the changes required in medical education and the growing need for trained educational leaders. Interestingly, through an informal follow-up in spring 2011 of the 11 schools which had indicated interest in initiating a fellowship, nine had not started a fellowship and the other two had few enroll in the programme. These schools cited either a change in administration, economic downturn or lack of faculty time or funds to pay for protected time as barriers. Future research should elucidate facilitators and barriers associated with the adoption and maintenance of medical education fellowships across the USA.

Our data suggest that fellowships have common elements: each serves similar groups of individuals and has a similar focus. But while similarities exist, we noted vast differences in the length and completion requirements. Some programmes require only ten contact hours while others involve over 500; similarly, some fellowships can be completed in less than a month while others take four years. Our results suggested that the projects required of fellows varied in complexity; however, most required a scholarly project. Even though most programmes focused on teaching, less than half required fellows to design or implement a curriculum and few required reflective writing, even though reflection has been indicated as an important part of teacher education and physician development (11). These results support the view that each medical education fellowship is designed to meet the local needs of the faculty (12), tailored to the time, expertise and monetary constraints of the institution.

Our results suggest that limited evaluation outcomes were collected by fellowships. Satisfaction was the most common form of programme evaluation. We propose that additional outcomes, including changes in the knowledge, skills and attitudes of graduates (such as quality and quantity of educational projects and teaching efforts, educational leadership positions and educational scholarship) and the influence of the fellowship on the institutional culture are important to evaluate (3, 13). We propose that sharing curricula, developing valid outcome measures and collecting data across institutions could help establish national guidelines or “best practices” among medical education fellowships.

Medical education fellowship programmes are increasingly part of medical schools across the US. These programmes provide institutions with a core of well-trained educational leaders who can guide the development of curricula and teach the increasingly complicated art and science of medicine (3, 6–9, 12–18). Results from this study can help to inform those charged with planning, implementing and/or evaluating this type of faculty development activity. They can also guide individuals who lead medical education fellowships by providing a baseline of information regarding curriculum focus, length and requirements, and programme evaluation methods across the country.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

References

- 1.McLean M, Cilliers F, Van Wyk JM. Faculty development: yesterday, today and tomorrow. Med Teach. 2008;30:555–84. doi: 10.1080/01421590802109834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinert Y, Mann K, Centeno A, Dolmans D, Spencer J, Gelula M, et al. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME Guide No. 8. Med Teach. 2006 Sep;28:497–526. doi: 10.1080/01421590600902976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Searle NS, Hatem CJ, Perkowski L, Wilkerson L. Why invest in an educational fellowship program? Acad Med. 2006;81:936–40. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000242476.57510.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hackbarth GM, Haddy FJ, Ajluni PB, Iglehart JK. Pursuit of an expanded physician supply. NEJM. 2008;359:764–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleming VM, Schindler N, Martin GJ, DaRosa DA. Separate and equitable promotion tracks for clinician-educators. JAMA. 2005;249:1101–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.9.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenbaum ME, Lenoch S, Ferguson KJ. Outcomes of a teaching scholars program to promote leadership in faculty development. Teach Learn Med. 2005;17:247–52. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1703_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gruppen LD, Frohna PZ, Anderson RM, Lowe KD. Faculty development for educational leadership and scholarship. Acad Med. 2003;78:137–41. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200302000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinert Y, Nasmith L, McLeod PJ, Conochie L. A teaching scholars program to develop leaders in medical education. Acad Med. 2003;78:142–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200302000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilkerson L, Hodgson C. A fellowship in medical education to develop educational leaders at UCLA. Acad Med. 1995;70:115–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199505000-00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatem CJ. Teaching approaches that reflect and promote professionalism. Acad Med. 2003;78:709–13. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200307000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epstein RM. Mindful practice. JAMA. 1999;282:833–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Searle NS, Thompson BM, Perkowski LC. Making it work: the evolution of a medical educational fellowship program. Acad Med. 2006;81:984–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000242474.90005.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lown BA, Newman LR, Hatem CJ. The personal and professional impact of a fellowship in medical education. Acad Med. 2009;84:1089–97. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ad1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jolly BC. Faculty development for curricular implementation. In: Norman GR, van de Vleuten CPM, Newble DI, editors. International handbook of research in medical education. Boston (MA): Kluwer Academic; 2002. pp. 945–67. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatem CJ, Lown BA, Newman LR. The academic health center coming of age: helping faculty become better teachers and agents of educational change. Acad Med. 2006;81:941–4. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000242490.56586.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gruppen LD, Simpson D, Searle NS, Robins L, Irby DM, Mullan PB. Educational fellowship programs: common themes and overarching issues. Acad Med. 2006;81:990–4. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000242572.60942.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moses AS, Heestand DE, Doyle LL, O'Sullivan PS. Impact of a teaching scholars program. Acad Med. 2006;81(Suppl 10):S87–S90. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000236538.29378.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moses AS, Skinner DH, Hicks E, O'Sullivan PS. Developing an educator network: the effect of a teaching scholars program in the health professions on networking and productivity. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21:175–9. doi: 10.1080/10401330903014095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]