Abstract

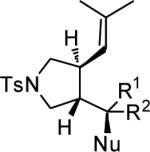

In this article the utility of phosphoramidite ligands in enantioselective AuI catalysis was explored in the development of highly diastereo- and enantioselective AuI-catalyzed cycloadditions of allenenes. A AuI-catalyzed synthesis of 3,4-disubstituted pyrrolidines and γ-lactams is described. This reaction proceeds through the enantioselective AuI-catalyzed cyclization of allenenes to form a carbocationic intermediate that is trapped by an exogenous nucleophile, resulting in the highly diastereoselective construction of three contiguous stereogenic centers. A computational study (DFT) was also performed to gain some insight into the underlying mechanisms of these cycloadditions. The utility of this new methodology was demonstrated through the formal synthesis of (–)-isocynometrine.

1. Introduction

The enantioselective synthesis of functionalized pyrrolidines has attracted significant interest due to their abundance in bioactive natural and unnatural products, and use as chiral ligands and organocatalysts.1 Their importance has inspired the development of diverse methods for their enantioselective construction including transition metal-catalyzed hydroamination,2 cycloaddition3 and cycloisomerization reactions.4 Despite these advances, enantioselective access to 3,4-substituted pyrrolidines5 remains a synthetic challenge. Over the past decade, homogeneous AuI catalysis has opened the door to a plethora of highly complex molecular frameworks.6 The operational simplicity and stability of AuI complexes to air and moisture has made them, arguably, a leading contender in the field of asymmetric catalysis. As a result, we sought a diastereo- and enantioselective AuI-catalyzed entry into 3,4-substituted pyrrolidines.

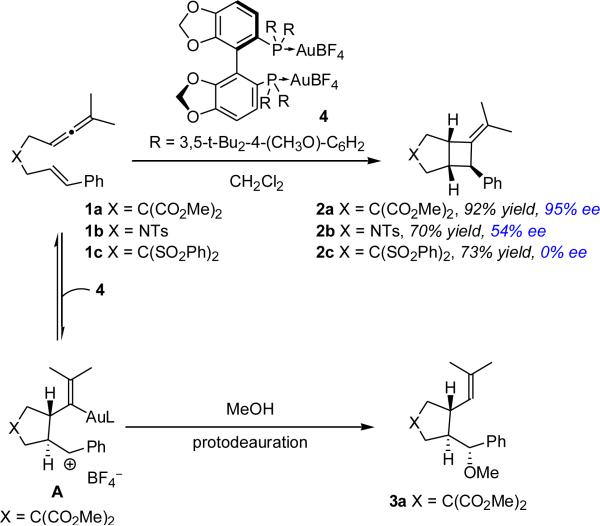

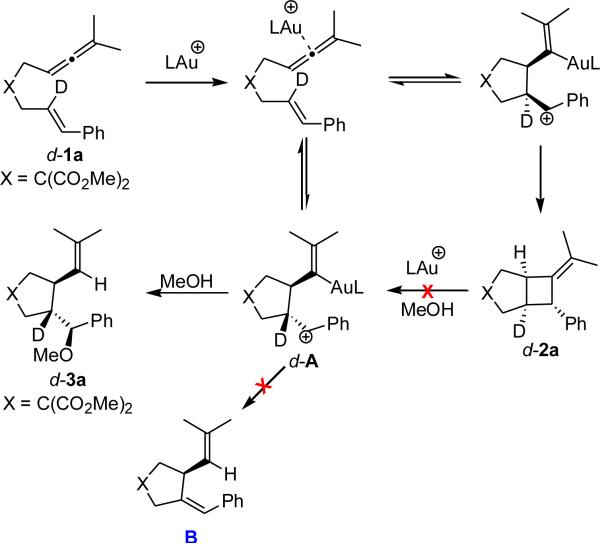

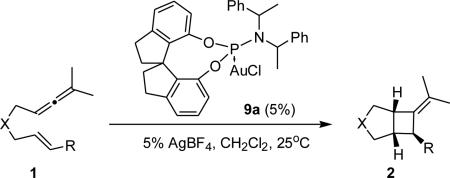

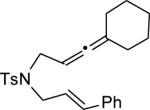

We had previously observed the formation of pyrrolidines during the investigation of the mechanism of the AuI-catalyzed [2+2]-cycloaddition of allenenes. These studies suggested that the trans-3,4-substituted pyrrolidines derived from kinetically generated cationic intermediate A (Scheme 1);7 however, attempts to trap A with MeOH using chiral biaryl bisphosphine ligands (4) that had been successfully employed in the enantioselective [2+2]-cycloadditions of allenenes provided methoxycyclization8 product 3a as a racemate.

Scheme 1.

AuI-catalyzed Cycloadditions of Allenenes.

Initially introduced by Kagan and Dang in 1971, bidentate chiral phosphines have remained the ligands of choice on many metal-catalyzed synthetic transformations.9 Expectedly, this tendency has been extended to the field of enantioselective gold(I) catalysis10 despite the pronounced preference of gold(I) to form two-coordinate linear complexes rather than the bidentate complexes typical formed with these ligands.11,12 These ancillary ligands are also expensive and difficult to synthesize, thwarting optimization efforts.

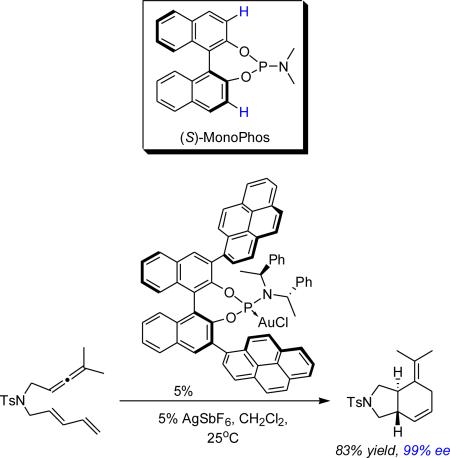

Recently we and others have shown the utility of tunable monodentate phosphite and phosphoramidite AuI catalysts in mediating enantioselective cycloadditions.13 First introduced to the asymmetric catalysis community in 1994, monodentate chiral phosphoramidites have remained useful ancillary ligands in many transformations.12 We initially became interested in this ligand class because their modular framework is readily constructed from commercially available enantiomerically pure compounds, thereby allowing for the straightforward preparation of large ligand libraries. We first reported the use of MonoPhos-AuOTf complex on the enantioselective Conia-Ene reaction in 2005 without success.14 It was not until we explored the enantioselective intramolecular AuI-catalyzed formal Diels-Alder cycloadditions of allene-dienes that a true need for the development of chiral phosphoramidite AuI-catalysts transpired. An inspection of MonoPhos-AuCl complex in its solid state suggested that ortho-substitution of its BINOL moiety would provide for a more defined steric environment.13a This idea was pursued with success, resulting in the chemoselective synthesis of the desired [4+2]-cycloadducts in excellent enantioselectivities (eq. 1). Consequently, we focus our studies on the AuI-catalyzed reactions of allenene 1a with this ligand class. Through these studies we uncovered two highly stereoselective phosphoramidite AuI catalysts expanding our repertoire of reagents and advancing our efforts in the enantioselective catalytic arena.

|

(1) |

2. Results and Discussion

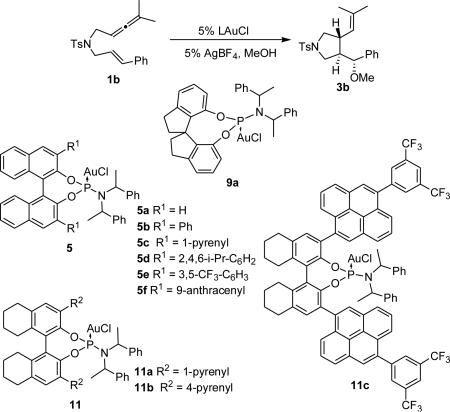

2.1 Enantioselective AuI-Catalyzed [2+2]-Cycloadditions of Allenenes. Scope and Limitations

We began our catalyst screen with BINOL-derived phosphoramidite catalysts 5. Employing unsubstituted complex (S,S,S)-5a resulted in low enantioinduction and, contrary to our expectations, introducing substituents in the 3,3'-positions on the BINOL moiety did not significantly improve the selectivity (entries 1-3). Exploring other backbones in our screen showed that VANOL-derived catalyst 7 produced 2b in a promising 70% ee (entry 6). However, attempts to improve this result by using what we thought would be a more hindered VAPOL backbone (8) instead resulted in a lower enantioselectivity (entry 6). However, complex 9a, containing a simpler spirobiindane-derived phosphoramidite, gave a promising hit (entry 7). Employing its diastereomer (S,R,R)-9a gave 2b in lower enantioselectivity confirming that (R,R,R)-9a corresponds to the match case. We then decided to explore the effect of the amine moiety of 9 on the product's enantioselectivity and catalysts 9b-d were synthesized and tested. Replacing the bis(1-phenylethyl)amine group for its pyrrolidine counterpart and utilizing a larger amine or a smaller alcohol moiety proved to be ineffective (entries 9-11).

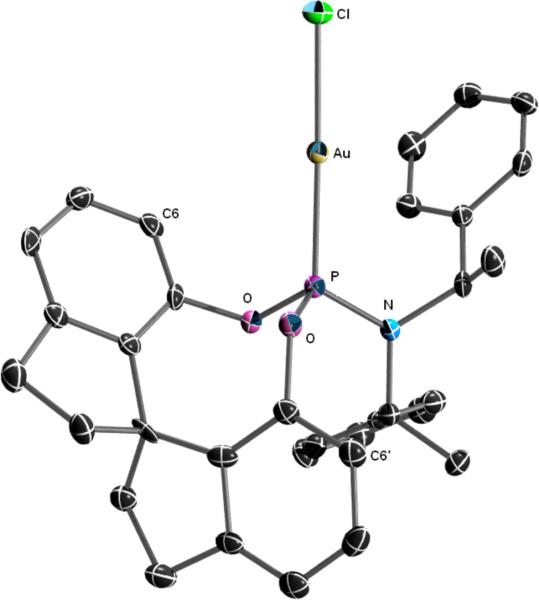

An inspection of complex 9a (Figure 1) in its solid state suggested that employing 6,6'-disubstituted spirobiindane phosphoramidite ligands might provide a steric environment similar to that found with catalysts 5.15 To access our 6,6'-disubstituted spirobiindane phosphoramidite gold(I) complexes we chose to employ a variation of the Beller-Köckritz Suzuki protocol which circumvents the protection and subsequent deprotection of both of SPINOL's alcohol moieties (see Supplementary Information for additional details).16 Unfortunately, utilizing catalysts 10 on the cycloaddition of allenene 1b did not result in improved enantioselectivities.

Figure 1.

Structure of complex (R,R,R)-9a in the solid state. Ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

We then decided to examine the scope of the [2+2]-cycloadditions of various allenenes with 9a. Catalyst 9a proved to be selective for several allenenes with varying tethers (Table 2, entries 2-4). Notably, bis-sulfone tethered 2c was obtained in 85% ee (entry 3), a large improvement when compared to that synthesized with 4 (Scheme 1). Nonetheless, catalyst 9a was unselective towards 1a, showing a complementary reactivity to 4. Both electron-withdrawing and -donating substituents as well as distinct substitution patterns on the arene moiety were well tolerated (entries 5-8). Interestingly cis-1b (entry 9) afforded the same enantiomer as that obtained from its trans counterpart in identical selectivity albeit in lower yield. This provides further evidence of the initial formation of A (Scheme 1), which, in the absence of an exogenous nucleophile, undergoes cycloreversion forming the more thermodynamically stable trans-1b. We decided to take a closer look at the hypothesized mechanism by means of a quantum mechanical study using the M06 flavor17 of density functional theory (DFT) which has been shown18 to be adequate for the description of organogold catalytic reactions. In doing so, we also hoped to gain some insight into the factors governing the alkoxycyclization reaction pathway leading to the formation of 3,4-substituted pyrrolidines.

Table 2.

Ligand Optimization for Phosphoramidite AuI-catalyzed [2+2]-Cycloaddition of 1 with (R,R,R)-9a.a

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | 2 | X | R | yield (%)b | ee (%)c |

| 1 | a | C(CO2Me)2 | Ph | 75 | 14 |

| 2 | b | N-Ts | Ph | 86 | 94 |

| 3 | c | C(SO2Ph)2 | Ph | 82 | 85 |

| 4 | d | N-Boc | Ph | 52 | 81 |

| 5 | e | N-Ts | 2-OMe-C6H4 | 82 | 80 |

| 6 | f | N-Ts | 3-OMe-C6H4 | 80 | 91 |

| 7 | g | N-Ts | 4-OMe-C6H4 | 72 | 80 |

| 8 | h | N-Ts | 4-Cl-C6H4 | 87 | 97 |

| 9d | b | N-Ts | Ph | 67 | 90 |

Reaction conditions: Cat (5 mol%), AgBF4 (5 mol%), dichloromethane, 25°C, 24h. Only one diastereoisomer was observed in all cases. Trans-2 was used in all cases except for those noted.

Isolated yields after silica gel flash column chromatography.

Enantiomeric excess determined by enantiodiscriminating HPLC (see Supporting Information).

From cis-1b.

2.2 Computational Analysis on the AuI-catalyzed Cycloadditions of Allenenes

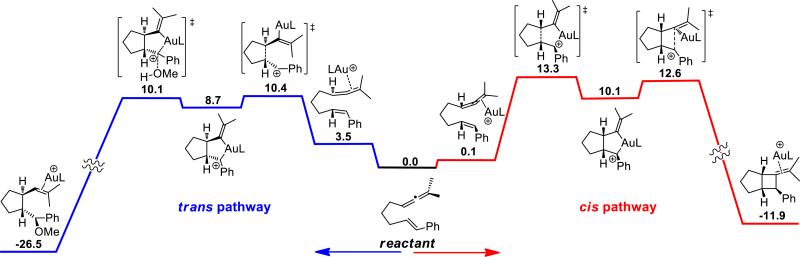

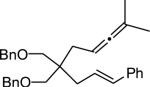

The potential energy surface was computed using the model phosphoramidite catalyst (MeO)2(Me2N)PAu+ as shown in Figure 2. Consistent with our previous predictions,18c our present computational study found a step-wise mechanism where the alkene adds to the gold-coordinated allene, leading to a vinyl-gold in a concerted fashion. There are two stereochemical arrangements for the relative position of the substituents on the formed cyclopentane ring: cis (in red) and trans (in blue) (Figure 2). Both pathways lead to intermediates where we found (in the most stable conformation) an interaction between the carbocation and gold that forms a 5-membered metallacycle. This electrostatic interaction results in carbocation stabilization by the full d-shell of the electron-rich gold. On the cis pathway the metallacycle ruptures to form the cyclobutane ring, effecting demetallation. Experimentally, exposing isolated 2a to (PhO)3PAuBF4 in the presence of MeOH did not give the alkoxycyclization product 3a, demonstrating that the formation of 2a is irreversible under these reaction conditions (Scheme 2). This result contrasts with Fürstner's findings that when exposed to a NHC-AuCl complex (NHC = N-heterocyclic carbene), compound 2a underwent rearrangement to the thermodynamically favored ring-expanded products, a process that was hypothesized to occur through the regeneration of an A-type carbocation.19

Figure 2.

DFT profile for the potential free energy surface for the cis (red) and trans (blue) cyclization pathways at the M06/LACV3P**++ level of theory corrected for CH2Cl2 as solvent in kcal/mol. L = P(OMe)2(NMe2).

Scheme 2.

AuI-cycloadditions of allenenes.

The trans pathway exhibits a similar cyclization leading to a 5-membered ring and a carbocation, notably, with a lower barrier than for the cis pathway (trans: 10.4 kcal/mol vs. cis: 13.3 kcal/mol). Moreover, we found a barrier for the addition of MeOH and demetallation20 which is lower than the rate determining barrier for the formation of product via the cis pathway. The absence of deuterium loss in the AuI-catalyzed formation of d-3a from d-1a suggests that the alkoxycyclization product is not formed from the addition of the MeOH to the styrene moiety of a 1,4-diene (B) but from a cationic intermediate A in agreement with our computational studies (Scheme 2).

Our results suggest that both cis and trans pathways are competitive, but in the presence of a nucleophile (MeOH), the trans pathway is preferred. On the other hand, in the absence of a viable nucleophile, the cis pathway is operative. These findings also suggest that a more polar solvent, such as MeNO2 could further increase the preference for the trans pathway, an observation that has been confirmed experimentally (see section 2.3). In addition, we speculate that the interaction between the carbocation and gold may serve to direct the attack of the nucleophile from the opposite side. With a clear view of the underlying mechanism on the AuI-catalyzed cycloadditions of allenenes we took a closer look at their enantioselective alkoxycyclization.

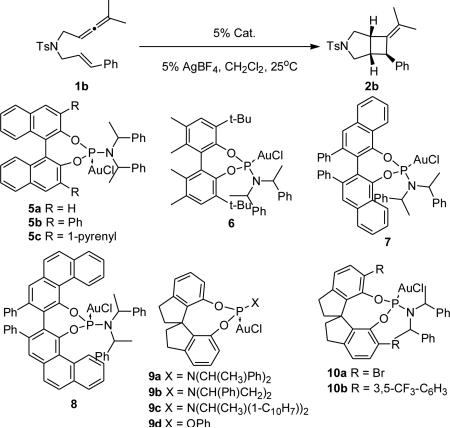

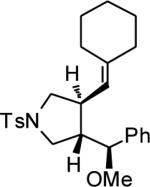

2.3 Enantioselective Synthesis of 3,4-disubstituted Pyrrolidines

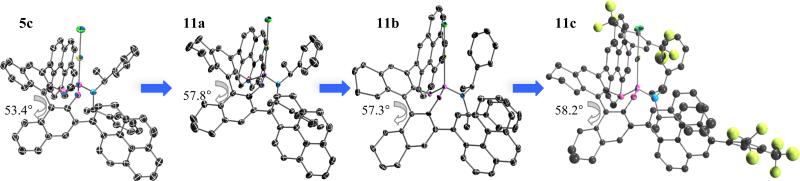

We first inspected the selectivity of catalyst 9a on the alkoxycyclization of 1b with MeOH, alas 3b was obtained in low selectivity (Table 3, entry 1). Even though the yield was improved by carrying the reaction in MeNO2, the enantiomeric excess remained low (entry 2). We then decided to test BINOL-derived phosphoramidites 5. Catalysts 5a gave 3b with low enantioselectivity; however, we found (S,S,S)-5a to be more selective than its diastereomer (R,S,S)-3a (Table 1, entries 3-4). Introducing substituents at the 3 and 3' positions of the binaphthol moiety increased the enantiomeric excess (entries 5-11), with 1-pyrenyl-disubstituted catalyst 5c providing 3b in up to 76% ee (entry 6). Attempts to improve this result by varying the solvent were unsuccessful (entry 7).21 Employing the H8-BINOL-analog 5c substantially improved the selectivity and the reaction yield each to 82%. The structures of the AuI complexes 5c and 11a in the solid state help rationalize this boost in enantioselectivity. The larger dihedral angle of 11a (57.75°) compared to 5c (53.39°) produces a shortening the Au-C3BINOL distance to 3.49Å from 3.63Å, thereby placing the Au-center in closer proximity to the chiral information (Figure 3). An examination of the solid state structure of 11a also led us to believe that a 4-pyrenyl moiety instead of its 1-pyrenyl isomer in 11a would extend the chiral pocket further outward. Indeed, 11b (Figure 3) catalyzed the cycloaddition/MeOH trapping of 1b with increased selectivity (88% ee, entry 13). We installed electron-deficient arenes on the 4-pyrenyl moiety of 11b in an effort to improve efficiency. We came to this hypothesis from the observed high reactivity of 5e, which allowed us to carry out the reaction at lower temperatures (entries 9-10). Although 11c mediated the formation of 1a with better selectivity even at room temperature (92% ee, entry 14), running the reaction at a lower temperature (0°C) produced superior results (entry 15).22 The improved selectivity of 11c when compared to 11b at room temperature might be due to an increased bite angle (58.2°) as observed in its solid state (Figure 3). probability level.

Table 3.

Ligand Optimization for the AuI-catalyzed Cycloaddition/Alkoxylation of Allenenes.a

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | Catalyst | temp. | yield (%)b | ee (%)c |

| 1d | (R,R,R)-9 | rt | 42 | 20(+) |

| 2 | (R,R,R)-9 | rt | 72 | 28(+) |

| 3 | (R,S,S)-5a | rt | 41 | 10(–) |

| 4 | (S,S,S)-5a | rt | 74 | 19(+) |

| 5 | (R,R,R)-5b | rt | 75 | 38(+) |

| 6 | (S,S,S)-5c | rt | 80 | 76(–) |

| 7d | (S,S,S)-5c | rt | 75 | 70(–) |

| 8 | (S,S,S)-5d | rt | 17 | 34(–) |

| 9 | (R,R,R)-5e | rt | 84 | 53(+) |

| 10 | (R,R,R)-5e | -15 °C | 86 | 70(+) |

| 11 | (R,R,R)-5f | rt | 87 | 49(+) |

| 12 | (R,R,R)-11a | rt | 82 | 82(+) |

| 13 | (S,S,S)-11b | rt | 86 | 88(–) |

| 14 | (S,S,S)-11c | rt | 86 | 92(–) |

| 15 | (S,S,S)-11c | 0 °C | 95 | 94(–) |

Reaction conditions: LAuCl (5 mol%), AgBF4 (5 mol%), MeOH (9 equiv), nitromethane, rt, 24h. In all experiments a small amount (<9%) of the corresponding [2+2]-cycloaddition product was also produced. The diastereoselectivity was >98:2 in all cases.

Isolated yields after silica gel flash column chromatography.

Enantiomeric excess determined by enantiodiscriminating HPLC (see Supporting Information).

Reaction run in dichloromethane.

Table 1.

Ligand Optimization for Phosphoramidite AuI-catalyzed [2+2]-Cycloaddition of 1b.a

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | Cat. | yield (%)b | ee (%)c |

| 1 | (S,S,S)-5a | 81 | 34(+) |

| 2 | (S,S,S)-5b | 91 | 14(+) |

| 3 | (S,S,S)-5c | 67 | 56(+) |

| 4 | (S,S,S)-6 | 34 | 60(+) |

| 5 | (S,S,S)-7 | 81 | 70(+) |

| 6 | (R,R,R)-8 | 77 | 64(–) |

| 7 | (R,R,R)-9a | 86 | 90(+)d |

| 8 | (S,R,R)-9a | 73 | 52(–) |

| 9 | (R,R,R)-9b | 87 | 32(+) |

| 10 | (R,R,R)-9c | 22 | 4(+) |

| 11 | (R)-9d | 88 | 32(+) |

| 12 | (R,R,R)-10a | 66 | 56(–) |

| 13 | (R,R,R)-10b | --- | --- |

Reaction conditions: Cat (5 mol%), AgBF4 (5 mol%), dichloromethane, 25°C, 24h. Only one diastereoisomer was observed in all cases.

Isolated yields after silica gel flash column chromatography.

Enantiomeric excess determined by enantiodiscriminating HPLC (see Supporting Information).

The enantioselectivity was increased to 99% ee after a simple crystallization.

Figure 3.

ORTEP representations of complexes 5c and 11a-c. Ellipsoids are drawn at the 50%

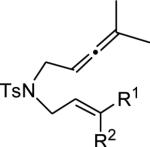

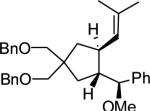

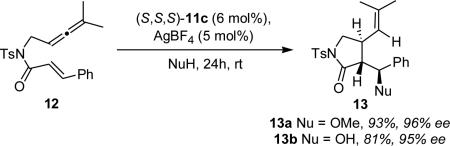

In order to examine the scope of the reaction, a variety of allenenes were synthesized and subjected to the optimized conditions for trapping with various alcohols (Table 4). Both electron-donating (entries 1-3) and -withdrawing (entry 4) substituents on the aromatic moiety were well tolerated, as were ortho-, meta- and para-substituents (entries 1-3).23 The expected cycloadducts were obtained in high yield and enantioselectivity when trapping 1b with several primary (entries 5-7) and secondary (entry 8) alcohols as nucleophiles. We were pleased to find that even water was a suitable trapping agent and alcohol 3l was isolated in good yield and enantioselectivity (entry 9). Even a tertiary ether could be synthesized from a trisubstituted olefin in excellent diastereo- (>98:2) and enantioselectivity (92%) (entry 12). The allene moiety was also varied with similar success (entry 13). Accordingly, electron-rich aryl nucleophiles24 could be employed in this transformation, producing the Friedel-Crafts product 3p in good yield (73%) and enantioselectivity (97%, eq 2).25

Table 4.

Substrate Scope for AuI-catalyzed Cycloaddition/Alkoxylation of Allenenes with 11c.a

| entry | Substrate | NuH | 3 | yield % | ee % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| R1, R2 | |||||

| 1 | 2-OMe-C6H4, H | MeOH | d | 73 | 96 |

| 2 | 3-OMe-C6H4, H | MeOH | e | 92 | 96 |

| 3 | 4-OMe-C6H4, H | MeOH | f | 90 | 94 |

| 4 | 4-Cl-C6H4, H | MeOH | g | 68 | 86 |

| 5 | Ph, H | EtOH | h | 90 | 92 |

| 6 | Ph, H | HOCH2(C(CH3)3) | i | 72 | 94 |

| 7 | Ph, H | HOCH2(HC=CH2) | j | 84 | 94 |

| 8 | Ph, H | HOCH(CH3)2 | k | 81 | 96 |

| 9 | Ph, H | H2O | l | 85 | 96 |

| 10 | Ph, H | MeOH | b | 95 | 94 |

| 11 | H, Ph | MeOH | b | 39 | 86 |

| 12 | Ph, Me | MeOH | m | 83 | 92 |

|

|

||||

| 13 | MeOH | n | 76 | 94 | |

|

|

||||

| 14 | MeOH | o | 86 | 72 |

Reaction conditions: 11c (6 mol%), AgBF4 (5 mol%), trapping agent (Nu) (9 equiv), 24h. For entries 5-10 the reaction was run at 0°C, all others were run at room temperature. In all experiments a small amount (<9%) of the corresponding [2+2]-cycloaddition product was also produced. The diastereoselectivity was >98:2 in all cases. Isolated yields after silica gel flash column chromatography. Enantiomeric excess determined by enantiodiscriminating HPLC (see Supporting Information).

Interestingly, cis-substituted allenene (cis-1b) afforded the same 2b isomer as its trans-1b counterpart, albeit in lower yield and enantioselectivity (entries 10-11). This observation and the conservation of enantioselectivity regardless of the nucleophile used (Table 4, entries 5-10) suggest that the cyclization is the enantiodetermining step. These findings are in stark contrast with the related 5-exo-dig cyclization/trapping of 1,6-enynes for which the nature of the nucleophile significantly affects enantioselectivity.8b,24b

|

(2) |

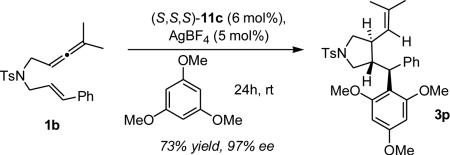

Additionally, 3,4-disubstituted γ-lactams 13a and 13b could be accessed through this methodology in high enantioselectivity (eq 3). The observed reactivity with amide substrate (12) prompted us to examine this alkoxycyclization reaction towards the synthesis of (–)-isocynometrine.

|

(3) |

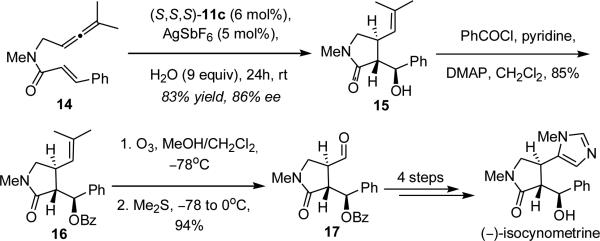

2.4 Formal Synthesis of (–)-isocynometrine

The utility of this methodology is exemplified by the synthesis of (–)-isocynometrine, an imidazole alkaloid isolated from the Cynomera species, known for its antitussive and analgesic properties.26 This alkaloid was first synthesized by Xu and co-workers through a Pd-catalyzed enyne cycloaddition introducing two of the three contiguous stereogenic centers in 53% ee.4e The third stereocenter was then installed by reduction of a phenyl ketone to its secondary carbinol in 2.5:1 dr. In our approach allenene 14 was subjected to the optimized reaction conditions in the presence of water yielding γ-lactam 15 in 83% and 86% ee. The resulting secondary alcohol in 15 was then converted to its benzoyl ester and the trisubstituted olefin was oxidatively cleaved with ozone yielding 17 in 80% (2 steps). The synthesis could then be completed as previously established in the literature to give (–)-isocynometrine.

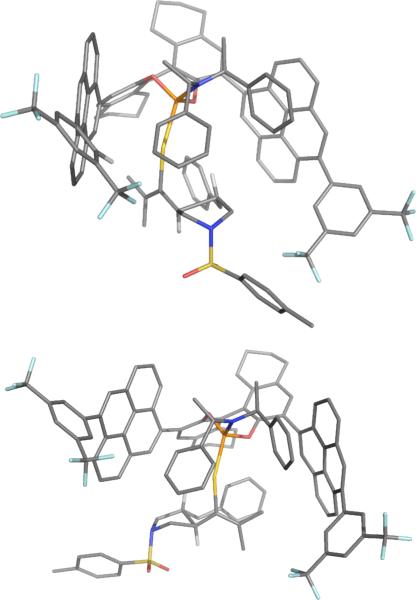

2.5 Computational study on the origin of enantioselectivity

Having established the general mechanism using a model ligand, we used molecular mechanics27 to investigate the conformational landscape starting from the X-ray structure of ligand (S,S,S)-11c on the fixed coordinates of the intermediates and transition structures. Ligand (S,S,S)-11c is composed of a (S,S) bis(1-phenylethyl)amine fragment and a 3,3'-functionalized (S)-octahydro-BINOL. Upon visual analysis of the catalyst-substrate complex, the octahydro BINOL group provides the axial chirality to the catalyst, while the bis(1-phenylethyl)amine group adds steric bulk, increasing the helical pitch. We performed a study of the possible relative rotational orientations of the phosphoramidite ligand and the substrate. Our conformational analysis suggests that the specific stereochemistry of the phenylethyl groups in (S,S)-bis(1-phenylethyl)amine may not effect direct enantiomeric discrimination, but may be critical in leveraging the performance of the BINOL moiety. Following our classical mechanics analysis, we subjected two pairs of selected conformations of the full structures of the enantiodetermining transition structures to DFT geometry optimization at the M06/LACVP* level of theory with a C–C distance constraint (1.994 Å as found for the model ligand). This methodology is thought to exhibit enough accuracy to visualize the key structural factors that govern the enantioselectivity.

Our structural analysis suggests that the groups at the 3,3'-positions on BINOL serve to orient the substrate by flanking it. This could explain the increase in enantioselectivity using pyrenyl substituents. The parallel placement of the pyrenyl groups form a channel in which the substrate can adopt two complementary orientations that lead to the different enantiomers. In one of these orientations, the N-tosyl pyrrolidine fragment points towards the bis(1-phenylethyl)amine group while the styrenyl and dimethylallyl groups point towards the H8-BINOL; alternatively, on the other orientation, the styrenyl and dimethylallyl groups point towards the bis(1-phenylethyl)amine group, while the N-tosyl pyrrolidine fragment points in the direction of the H8-BINOL. The enantioselectivity originates from the relative interactions between these groups. We identified the following key ligand structural directives: 1) the aligning of the substrate by the 3,3'-BINOL substituents, 2) the steric interactions provided by the bis(1-phenylethyl)amine group, and the 3) steric interactions provided by the “downward” facing H4-naphthyl group. We also recognized that a higher dihedral angle of the BINOL group increases the steric interaction of the enantiodiscriminating H4-naphthyl group, which could explain why increasing the dihedral correlated with higher enantioselectivities.

3. Conclusions

The successful development of newly AuI-catalyzed transformations depends largely on the ability to design inexpensive ligands that are easy to prepare and tune for a specific chemical transformation. Within this context, this report serves to further demonstrate the potential utility of phosphoramidite ligands in enantioselective AuI-catalysis. We uncovered two new highly selective catalysts on the cycloadditions of allenenes. Commercially available, small, SIPHOS-PE-derived catalyst 9a proved to be highly selective for the [2+2]-cycloadditions of allenenes. Importantly, catalyst 9a was particularly selective towards nitrogen and bis-sulfone tethered substrates, both of which underwent this transformation with previously reported bis-phosphine-derived 4 in low enantioselectivity. This report also describes a new AuI-catalyzed cyclization/alkoxylation for the conversion of allenenes to trans-3,4-disubstituted pyrrolidines and γ-lactams. The reaction allows for the highly diastereo- and enantioselective synthesis of these heterocycles containing three contiguous stereocenters. Central to the success of this effort was the use of bulky mono-phosphorous-AuI complex 11c. We also studied these reactions computationally using the M06 functional (DFT) to gain insight into key factors determining the mechanism and the enantioselectivity. The utility of this methodology is demonstrated by the formal synthesis of (–)-isocynometrine.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 3.

Enantioselective synthesis of (–)-isocynometrine.

Figure 4.

Views for the matched (top) and mismatched (bottom) structures minimized at the M06/LACVP* level of theory.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the National Institute of General Medical Services (GM073932), and Amgen. A.Z.G. thanks the NIH for a postdoctoral fellowship. We thank Vincent Medrán and Pablo Mauleón for preliminary experiments and Johnson Matthey for a gift of AuCl3. We would also like to thank Dr. Antonio DiPasquale for his assistance in collecting and analyzing crystallographic data. Computational facilities were funded by grants from ARO-DURIP and ONR-DURIP.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Computational details, experimental procedures and compound characterization data is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.a Cordell GA, editor. The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology. Vol. 54. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]; b O'Hagan D. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2000;17:435. doi: 10.1039/a707613d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Schomaker JM, Bhattacherjee JY, Borhan B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:1996. doi: 10.1021/ja065833p. and references cited therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Hanessian S, Yun H, Tintelnot-Blomley M. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:6746. doi: 10.1021/jo050740w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.For selected recent examples of enantioselective synthesis of pyrrolidines see: Zhang Z, Bender CF, Widenhoefer RA. Org. Lett. 2007;9:2887. doi: 10.1021/ol071108n. Hamilton GL, Kang EJ, Mba M, Toste FD. Science. 2007;317:496. doi: 10.1126/science.1145229. LaLonde RL, Sherry BD, Kang EJ, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:2452. doi: 10.1021/ja068819l. Shen X, Buchwald SL. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:564. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905402. Mai DN, Wolfe JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:12157. doi: 10.1021/ja106989h.

- 3.a Cabrera S, Arrayas RG, Carretero JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:16394. doi: 10.1021/ja0552186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Saito S, Tsibogo T, Kobayashi S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:5364. doi: 10.1021/ja0709730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zeng W, Chen G-Y, Zhou Y-G, Li Y-X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:750. doi: 10.1021/ja067346f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Najera C, Retamosa MG, Sansano JM. Angew. Chem,. Int. Ed. 2008;47:6055. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Wang C-J, Liang G, Xue Z-Y, Gao F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:17250. doi: 10.1021/ja807669q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Parsons AT, Smith AG, Neel AJ, Johnson JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:9688. doi: 10.1021/ja1032277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a Cao P, Zhang X. Angew. Chem,. Int. Ed. 2000;39:4104. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20001117)39:22<4104::aid-anie4104>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lei A, Waldrich JP, He M, Zhang X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002;41:4527. [Google Scholar]; c Chakrapani H, Liu C, Widenhoefer RA. Org. Lett. 2003;5:157. doi: 10.1021/ol027196n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Jang H-Y, Hughes FW, Gong H, Zhnag J, Brodbelt JS, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6174. doi: 10.1021/ja042645v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Xu W, Kong A, Lu X. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:3854. doi: 10.1021/jo060288w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Rhee JU, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:10674. doi: 10.1021/ja0637954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Nicolaou KC, Li A, Ellery SP, Edmonds DJ. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:6293. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.3,4-Substituted pyrrolidines comprise a structural motif commonly found in natural products and biologically active molecules: Farwick A, Helmchen G. Org. Lett. 2010;12:1108. doi: 10.1021/ol1001076. Ohki S, Nagasaka T, Matsuda H, Ozawa N, Hamaguchi F. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1986;34:3606. doi: 10.1248/cpb.34.3606. Okazaki Y, Ishizuka A, Ishihara A, Nishioka T, Iwamura H. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:3830. doi: 10.1021/jo0701740. Yu S, Qin D, Shangary JC, Wang G, Ding K, McEachern D, Qiu S, Nikolovska-Coleska Z, Miller R, Kang S, Yang D, Wang S. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:7970. doi: 10.1021/jm901400z. Ali A, Ahmad VU, Ziemer B, Liebscher J. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2000;11:4365. Clayden J, Knowles FE, Menet CJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:3397. Cook GR, Sun L. Org. Lett. 2004;6:2481. doi: 10.1021/ol049087+. Lian G-Y, Yu J-D, Yang H-F, Lin F, Gao Q, Zhang D-W. Chem. Lett. 2007;36:408. Han X, Luo J, Liu C, Lu Y. Chem. Commun. 2009:2044. doi: 10.1039/b823184b.

- 6.For a review on enantioselective Au-catalysis see: Widenhoefer RA. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:5382. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800219. For recent reviews on gold-catalyzed reactions see: Fürstner A. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:3208. doi: 10.1039/b816696j. Shen HC. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:7847. Gorin DJ, Sherry BD, Toste FD. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:3351. doi: 10.1021/cr068430g. Li Z, Brouwer C, He C. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:3239. doi: 10.1021/cr068434l. Gorin DJ, Toste FD. Nature. 2007;446:395. doi: 10.1038/nature05592. Hashmi ASK, Hutchings GJ. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:7896. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602454.

- 7.Luzung MR, Mauleon P, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12402. doi: 10.1021/ja075412n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.For examples of Pt- and Au-catalyzed enantioselective alkoxycyclization reactions of enynes see: Charrualt L, Michelet V, Taras R, Gladiali S, Genet JP. Chem. Commun. 2004:850. doi: 10.1039/b400908h. Muňoz MP, Adrio J, Carretero JC, Echavarren AM. Organometallics. 2005;24:1293. Michelet V, Charrualt L, Gladiali S, Genet JP. Pure Appl. Chem. 2006;78:397. Martinez A, Garcia-Garcia P, Fernandez-Rodriguez MA, Rodriguez F, Sanz R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:4633. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001089. Sethofer S,G, Mayer T, Toste FDJ. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:8276. doi: 10.1021/ja103544p. Chao C-M, Genin E, Toullec PY, Genet J-P, Michelet V. J. Organomet. Chem. 2009;694:538.

- 9.Shimizu H, Nagasaki I, Saito T. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:5405. [Google Scholar]

- 10.For the use of bisphosphine gold(I) catalysts in enantioselective transformations see: Melhado AD, Amarante GW, Wang ZJ, Luparia M, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011:133. doi: 10.1021/ja1095045. dx.doi.org/10/1021/ja1095045. Yao L-F, Wei Y, Shi MJ. Org. Chem. 2009;74:9466. doi: 10.1021/jo902261r. LaLonde RL, Wang ZJ, Mba M, Lackner AD. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:598. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905000. Kleinbeck F, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9178. doi: 10.1021/ja904055z. Zhang Z, Lee SD, Widenhoefer RA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5372. doi: 10.1021/ja9001162. Uemura M, Watson IDG, Katsukawa M, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:3464. doi: 10.1021/ja900155x. Watson IDG, Ritter S, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:2056. doi: 10.1021/ja8085005. Chao C-M, Vitale MR, Toullec PY, Genêt J-P, Michelet V. Chem – Eur. J. 2009;15:1319. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802341. Luzung MR, Mauleón P, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12402. doi: 10.1021/ja075412n. Tarselli MA, Chianese AR, Lee SJ, Gagné MR. Angew. Chem,. Int. Ed. 2007;46:6670. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701959. Liu C, Widenhoefer RA. Org. Lett. 2007;9:1935. doi: 10.1021/ol070483c. LaLonde RL, Sherry BD, Kang EJ, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:2452. doi: 10.1021/ja068819l. Zhang Z, Widenhoefer RA. Angew. Chem,. Int. Ed. 2007;46:283. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603260. Johansson MJ, Gorin DJ, Staben ST, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:18002. doi: 10.1021/ja0552500.

- 11.a Fürstner A, Davies PW. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:3410. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Shapiro ND, Toste FD. Synlett. 2010:675. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1219369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teichert JF, Feringa BL. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:2486. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a González AZ, Toste FD. Org. Lett. 2010;12:200. doi: 10.1021/ol902622b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Teller H, Flugge S, Goddard R, Fürstner A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:1949. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Alonso I, Trillo B, López F, Montserrat S, Ujaque G, Castedo L, Lledós A, Mascareňas JL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:13020. doi: 10.1021/ja905415r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corkey BK, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:17168. doi: 10.1021/ja055059q. In 2005 Echavarren et al. also showed an unsuccessful (2% ee) example of the use of a phosphoramidite Au(I) catalyst: see ref. 8b.

- 15.Yang Y, Zhu S-F, Duan H-F, Zhou C-Y, Wang, Zhou Q-L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:2248. doi: 10.1021/ja0693183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartoszek M, Beller M, Deutsch J, Klawonn M, Köckritz A, Nemati N, Pews-Davtyan A. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:1316. [Google Scholar]

- 17.a Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. Theo. Chem. Acc. 2008;120:215. [Google Scholar]; b Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:157. doi: 10.1021/ar700111a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.a Torker S, Merki D, Chen P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:4808. doi: 10.1021/ja078149z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Benitez D, Shapiro ND, Tkatchouk E, Wang YM, Goddard WA, Toste FD. Nature Chem. 2009;1:482. doi: 10.1038/nchem.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Benitez D, Tkatchouk E, Gonzalez AZ, Goddard WA, Toste FD. Org. Lett. 2009;11:4798. doi: 10.1021/ol9018002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Wang ZJ, Benitez D, Tkatchouk E, Goddard WA, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:13064. doi: 10.1021/ja105530q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alcarazo M, Stork T, Anoop A, Thiel W, Fürstner A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:2542. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.We also found a barrier of 22.9 kcal/mol for the formation of a cyclobutane ring via the trans pathway.

- 21.For a full account of all catalysts screened and different reaction conditions used refer to the Supporting Information.

- 22.Varying the counterion (OTf, SbF6, PF6) proved to be inconsequential to the enantioselectivity of the reaction.

- 23.An aryl substituent on the substrate's olefinic moiety proved to be necessary to achieve reactivity in the [2+2]-cycloaddition and alkoxycyclization reactions. For example, independent reaction of a dimethylsubstituted-olefin containing substrate with 9a and 11c (in the presence of MeOH) in dichloromethane (12 h, rt) resulted in the recovery of the starting material.

- 24.For a Pt- and Au-catalyzed enantioselective cyclization/hydroalkylation see: Toullec PY, Chao C-M, Chen Q, Gladiali S, Genet JP, Michelet V. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008;350:2401. Chao C-M, Vitale MR, Toullec PY, Genet J-P, Michelet V. Chem. Eur. J. 2009;15:1319. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802341.

- 25.We attempted to recover both 9a and 11c after their use as catalysts in the corresponding [2+2]-cycloaddition and alkoxycyclization reactions of 1b without success. For successful recycling of related catalysts see ref 13a.

- 26.a Chiaroni A, Riche C, Tchissambou L, Khuong-Huu F. J. Chem. Res. (S) 1981:182. [Google Scholar]; b Tchissambou L, Benechie M, Khuong-Huu F. Tetrahedron. 1982;38:2687. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halgren TA. J. Comput. Chem. 1996;17:490. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.