Abstract

Defects in cilia formation and function result in a range of human skeletal and visceral abnormalities. Mutations in several genes have been identified to cause a proportion of these disorders, some of which display genetic (locus) heterogeneity. Mouse models are valuable for dissecting the function of these genes, as well as for more detailed analysis of the underlying developmental defects. The short-rib polydactyly (SRP) group of disorders are among the most severe human phenotypes caused by cilia dysfunction. We mapped the disease locus from two siblings affected by a severe form of SRP to 2p24, where we identified an in-frame homozygous deletion of exon 5 in WDR35. We subsequently found compound heterozygous missense and nonsense mutations in WDR35 in an independent second case with a similar, severe SRP phenotype. In a mouse mutation screen for developmental phenotypes, we identified a mutation in Wdr35 as the cause of midgestation lethality, with abnormalities characteristic of defects in the Hedgehog signaling pathway. We show that endogenous WDR35 localizes to cilia and centrosomes throughout the developing embryo and that human and mouse fibroblasts lacking the protein fail to produce cilia. Through structural modeling, we show that WDR35 has strong homology to the COPI coatamers involved in vesicular trafficking and that human SRP mutations affect key structural elements in WDR35. Our report expands, and sheds new light on, the pathogenesis of the SRP spectrum of ciliopathies.

Main Text

There are a number of recessive disorders characterized by skeletal dysplasia and multiorgan anomalies,1 some of which have been shown to be caused by mutations in the development, structure, or function of primary cilia (ciliopathies).2 Short-rib polydactylies (SRPs) are a prime example, being a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by skeletal defects, short ribs and limbs, and polydactyly. Visceral features can include polycystic kidneys, laterality defects, and cardiovasular and brain abnormalities. SRPs have been classified into four types, (Saldino-Noonan syndrome, type I [MIM 263530]; Majewski syndrome, type II [MIM 263520]; Verma-Naumoff syndrome, type III [MIM 263510]; Beemer-Langer syndrome, type IV [MIM 269860]), which display clinical and molecular overlap. Although locus heterogeneity has been demonstrated in SRP (see below), the relative contribution of both allelic heterogeneity and genetic background modification remains unclear. This question extends to other disorders that share similar overlapping clinical features. Asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy (ATD, Jeune syndrome [MIM 208500]) has skeletal features similar to those of SRP, and patients usually die in infancy, although some survive and later may develop liver and kidney disease and retinal degeneration.3 Ellis van Creveld syndrome (EVC, chondroectodermal dysplasia [MIM 22550]) is most similar histologically to SRP III but often presents postnatally, with distinct radiological and clinical features such as congenital heart disease, supernumerary digits, and ectodermal dysplasia.1 In addition, patients with cranioectodermal dysplasia (CED, Sensenbrenner syndrome [MIM 218330]) display craniofacial and skeletal abnormalities, hair and tooth defects, and variable liver, kidney, brain, and retinal anomalies.4

Primary cilia are complex organelles protruding from the surface of nondividing cells. Their formation is organized by the basal body; a modified centriole structure from which the microtubule-based axoneme extends. The assembly and maintenance of cilia requires the dynamic bidirectional movement of the multiprotein complexes along the axoneme from cell body to cilia tip.5 This process, termed intraflagellar transport (IFT), involves a conserved core machinery organized into trains composed of either IFT-B (anterograde) or IFT-A (retrograde) components and is driven by kinesin or dynein molecular motors, respectively.6–8 In addition to the transport of structural units, IFT is also essential for the localization and function of key developmental signaling components, such as the Gli transcription factors, which transduce Hedgehog (Hh) signaling.9 The loss of Hh regulation may be a hallmark of some clinical features observed in ciliopathies.

In cases in which mutated genes have been identified in skeletal dysplasias, it is not known whether a correlation exists between severity of disease and the particular protein or ciliary process affected. Homozygous and compound-heterozygous mutations in the retrograde dynein motor DYNC2H1 (MIM 603297) have recently been identified in cases of both SRP type III and ATD/Jeune syndrome,10,11 and IFT80 (MIM 611177), which encodes a component of the anterograde IFT-B complex, is mutated in some other cases of ATD.12 In contrast, mutations recently identified in the less severe CED/Sensenbrenner syndrome affect components of the IFT-A retrograde complex IFT122 (MIM 606045)13 or WDR35 (MIM 613602).14 Most recently, mutations in Never-in-mitosis Kinase 1 (NEK1 [MIM 604588]), a gene involved in initiating ciliogenesis,15–17 were identified in several SRP type II cases, including a potential example of digenic diallelic inheritance with DYNC2H1.18 Mouse mutations have been found in many of these genes17,19–22 and will be valuable models for understanding ciliopathic phenotype-genotype correlations.

We previously identified a New Zealand family of Maori descent with two consecutive pregnancies complicated by an unclassifiable SRP syndrome that was most similar to SRP type III but was novel in that it was associated with acromesomelic hypomineralisation and campomelia.23 These affected siblings exhibited several additional hallmarks of ciliopathic disease, including polysyndactyly, laterality defects, and cystic kidneys. After institutional ethics approval and informed consent, human samples were collected for molecular analysis. Using genome-wide SNP genotyping and CNV analysis, we mapped the disease locus to a 5.5 Mb region of chromosome 2p24 (Figure S1A available online) and identified a homozygous deletion of three SNPs within WDR35 (NM_001006657.1) (Figure S1B). This deletion was heterozygous in both parents and the unaffected sibling but was homozygous in the two affected siblings. Direct sequencing of the parents and affected siblings over this region identified a 2847 bp deletion spanning exon 5 of WDR35 (Figure 1C). PCR analysis of cDNA from patient cell lines confirmed the loss of the 129 bp exon 5 from the WDR35 mRNA (Figure 1D). WDR35 encodes two isoforms that share seven closely spaced WD40 repeats at the amino terminus and a tetratricopeptide repeat-like motif at the carboxyl terminus (Figure 1E). WD40 repeats are involved in intracellular trafficking, cargo recognition, and binding,24,25 and the WDR35Δ5 mutation results in the in-frame deletion of one of these repeats (Figure 1E). WDR35 is orthologous with Ift121, which fractionates with complex A IFT particles in C. reinhardtii25 and mammals.26 Mutations in the C. elegans ortholog (ifta-1) display classic truncated retrograde cilia phenotypes with accumulations of IFT machinery and transport profiles consistent with phenotypes observed when other complex A subunits are mutated.27 We also performed candidate-gene sequencing of WDR35 in two cases with a clinical diagnosis of Jeune syndrome and four additional cases with severe SRP phenotypes (two unclassifiable SRPs, one Beemer-Langer [type IV] SRP, and one Majewski [type II] SRP). Heteroallelic mutations in WDR35 were identified in one fetus (Figure S1C) with an SRP phenotype associated with extreme micromelia, postaxial polydactyly, and facial abnormalities (Figures 1A and 1B). A de novo nonsense mutation (c.1633C>T [p.Arg545X]) was identified on the paternal allele, and a missense mutation affecting a highly conserved tryptophan residue (c.781T>C [p.Trp261Arg]; Figure 4A) was shown to be maternally inherited.

Figure 1.

WDR35 Is Mutated in Atypical Short-Rib Polydactyly Syndrome in Humans and in the yeti Mutant Mouse

(A and B) Characteristic postaxial polydactyly, extreme micromelia, and short ribs (A) as presented in postmortem survey of 13 week conceptus (SRP-3-1) (B).

(C) Genomic PCR spanning exons 4, 5, or 6 of WDR35 from DNA of parents (SRP-1-1, SRP-1-2) or affected concepti (SRP-1-4, SRP-1-6). Deletion of a 2847 bp genomic fragment (2:20177392-20180238, assembly GRCh37) results in the loss of exon 5 in homozygous individuals. Reaction products for the control (C1) and no template (-ve) are shown.

(D) RT-PCR amplification of WDR35 spanning exons 4–6 from affected concepti (SRP-1-4, SRP-1-6) and control fibroblasts (C1, C2).

(E) Schematic of the predicted domain organization of two coding human WDR35 transcripts, with or without exon 11 (violet). The location of the WDR35 mutations in SRP-1 (blue; homozygous SRPΔ5) and SRP-3 (p.Trp261Arg and p.Arg545X) -affected concepti are shown. The splice acceptor mutation at the intron 21-exon 22 junction in yeti mice is indicated (∗).

(F–K) Gross embryonic phenotypes of wild-type (F–H) compared to yeti mutant littermates (I–K). Embryonic day 12.5 (E12.5) forelimb (F, I) and hindlimb (G, J) defects in yeti mouse mutants include impaired outgrowth along the proximal-distal axis and polysyndactyly. (H, K) E11.5 transverse hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections of the Wdr35yet/yet thoracic cavity show failure of the somite derivatives, such as the sclerotome (sc) derivatives (ri, ribs; ve, vertebra), to migrate out from the midline in mutants and tracheoesophageal fistula with hypoplastic lungs (asterisk).

(L) RT-PCR amplification of a Wdr35 fragment covering exons 21–24 shows the presence of aberrantly spliced of transcripts in the yeti mutant (white arrowheads) compared to wild-type (black arrowhead).

(M) Whole-mount in situ hybridization of Wdr35 in E10.5 wild-type and yeti littermates shows nonsense-mediated decay of mRNA in mutant embryos.

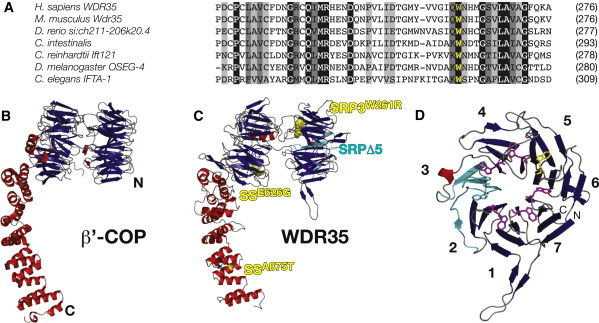

Figure 4.

Structural Similarities between WDR35 and the Canonical COPI Coat Complex Suggest Conserved Functional Importance of the N-Terminal WD40-like β-Propeller

(A) Amino acid sequence alignment of WDR35 sequence at W261 (yellow) demonstrates complete conservation of the tryptophan residue. WDR35 sequences are from Homo sapiens (ENST00000345530), Mus musculus (ENSMUST00000085745), Danio rerio (XP_693887.2), Ciona intestinalis (ENSCINT0000018168), Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (XP_001702021), Drosophila melanogaster (FBtr0072797), and Caenorhabditis elegans (C54G7.4).

(B and C) (B) Ribbon diagram of S. cerevisiae β′−COP (PDB ID: 3mkqA) from the crystal structure29 and the predicted architecture of human WDR35 (residues 6–933) based on homology modeling with the use of the yeast β′-COP structure as a template (C). For details of the protein structure modeling, see Figure S6. Starting from its N terminus (N), WDR35 is predicted to have two seven-bladed β-propeller domains (viewed side-on in the presented orientation) followed by an α-solenoid domain composed of the TPR-like repeat α helices. SRPΔ5 mutants are predicted to lose one full blade (cyan) of the N-terminal β-propeller domain. The p.Trp261Arg mutation affects a key tryptophan residue (yellow sphere) on the axial face of this same β-propeller in conceptus SRP-3-1. β strands are shown as blue arrows and α helices as red ribbons. Sensenbrenner missense mutations p.Glu626Gly and p.Ala875Thr,14 highlighted in yellow, affect residues outside this domain.

(D) Ribbon diagram of the proposed structural model for the N-terminal seven-bladed WD40-like β-propeller (residues 6–330) of human WDR35, with β strands shown in blue and the α-helix in red. Seven key tryptophan residues that are central to the WD-like repeats are shown as purple sticks; p.Trp261Arg is located in blade 6 and is shown as yellow sticks. Deletion of WDR35Δ5 leads to an in-frame deletion of four offset β strands (2d–3c: cyan) resulting in the loss of a full blade of the β-propeller. Amino and carboxy-termini are labeled with N and C, respectively. Blades of the propeller are numbered according to the secondary structure alignment in Figure S6.

Independently, we isolated the mutant mouse line yeti in a recessive ENU mutagenesis screen for genes affecting embryonic development. Mutant embryos die before late day 12.5 postcoitum (12.5 dpc) and exhibit a range of severe defects. They display cardiovascular defects including generalized edema, hemorrhages, and a randomized and mislooped heart tube. Delayed and randomized embryo turning is also observed, and polysyndactlyly is seen in rare, surviving, later-stage embryos (Figures 1I and 1J). Additionally, yeti mutants display failure of the somite derivatives, including the putative ribs, to migrate and properly differentiate (Figure 1K), hypoplastic lungs with tracheal-esophageal fistula, and diaphragmatic hernia. We mapped the yeti locus to a 3.5 Mb interval between rs6278243 and rs29154438 on chromosome 12 and undertook genomic sequencing of candidate genes. A single G>A mutation was identified in the splice acceptor site of exon 22 of Wdr35 (Figure 1E; chr12:9026683, ENSMUST00000085745, NCBIM37). RT-PCR analysis of cDNA from yeti mutant litters using primers in the adjacent exons confirmed aberrant splicing of the Wdr35 mRNA in heterozygous and homozygous yeti embryos (Figure 1L). Sequencing of these mutant splice variants revealed frameshifts in all yeti transcripts. In situ hybridization with 5′ and 3′ UTR Wdr35 riboprobes in mutant embryos revealed that mutant transcripts are subject to nonsense-mediated decay (Figure 1M). Noncomplementation of the yeti allele with an embryonic-stem-cell-derived “targeted trap” null tm2a allele of Wdr35 proves that the yeti mutant phenotype is due to this point mutation in Wdr35 (Figure S2). The phenotypic parallels, in particular polydactyly and failure of migration and differentiation of somite derivatives leading to absent or shortened ribs, strongly suggest that the human mutations in WDR35, like the mouse mutations, result in a complete loss of function.

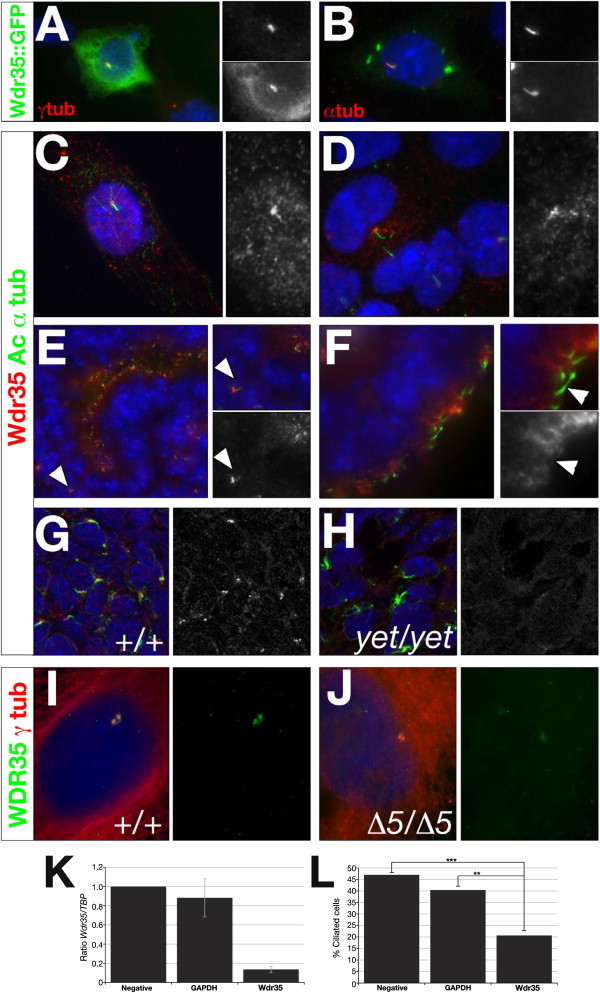

Little is functionally known about mammalian WDR35 aside from its biochemical association with other IFT-A components,26 so we characterized the cellular and in vivo localization of WDR35. Initially, we generated a full-length mouse Wdr35 protein tagged with GFP and expressed it in cultured cells. Significant staining was observed in the periciliary region in mouse NIH 3T3 cells, shown by partial colocalization with γ-tubulin (Figure 2A). In IMCD3 cells, which have more prominent cilia, Wdr35::GFP was also detected along the cilia axonemes, where it colocalized with acetylated α-tubulin (Figure 2B). To examine endogenous Wdr35 localization, we generated two independent antibodies directed against different, unique epitopes. Immunofluorescence studies in IMCD3 cells confirmed that Wdr35 accumulated at and around centrosomes and basal bodies of serum-starved cells, with fainter punctate staining along the cilia axoneme (Figures 2C and 2D). Immunofluorescence analysis of wild-type mouse sections labeled both primary and specialized cilia, as well as centrosomes, throughout the embryo. The intensity of staining was enriched in highly ciliated tissues, including the developing lung and nervous system (Figures 2E and 2F, Figure S4). Importantly, this WDR35 localization was lost in yeti mutant sections, as shown in the limb bud mesenchyme at 11.5 dpc (Figures 2G and 2H). Likewise, WDR35Δ5 SRP fibroblasts had only remnant expression of endogenous WDR35Δ5 (Figures 2I and 2J). Collectively, these data suggest that both WDR35Δ5 and yeti are loss-of-function alleles of WDR35. Given WDR35's subcellular localization and the gross ciliopathic phenotype of these mammalian mutants, our data suggest that WDR35 is an essential component of the cilia. To independently verify that WDR35 is required for ciliogenesis, we used a siRNA strategy to knock down expression of Wdr35 in NIH 3T3 cells and quantified the number of cells with cilia. Reduction of Wdr35 mRNA levels by 85% resulted in a 50% reduction in the number of ciliated cells compared to the scrambled siRNA control (Figures 2K and 2L).

Figure 2.

Wdr35 Localizes to Cilia and Is Required for Ciliogenesis

(A and B) NIH-3T3 (A) or IMCD3 (B) cells were microporated with full-length mouse Wdr35::GFP and serum starved for 36 hr before costaining with antibodies directed against γ-tubulin (A) or acetylated α-tubulin (red; B). Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Magnification of regions of interest are shown in singl-channel images indicating colocalization.

(C and D) IMCD3 cells were serum starved for 36 hr before costaining with antibodies directed against acetylated α-tubulin (green) and Wdr35 (red; C, 085 antibody; D, 02 antibody). Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue).

(E and F) Wild-type 13.5 dpc mouse kidney (E) and choroid plexus (F) sections were costained with antibodies directed against acetylated α-tubulin (green) and Wdr35 (red, 085 antibody). Nuclei are stained with TOTO-3 (blue). Primary cilia in the mesenchyme (E) and ciliated epithelia lining lumen (F) are indicated.

(G and H) Shown are 0.4 μm confocal images of section immunohistochemistry of 11.5 dpc limb-bud mesenchyme from wild-type (G) and Wdr35yet/yet (H) embryos stained with antibodies directed against acetylated α-tubulin (green), Wdr35 (085 antibody: red), and TOTO-3 (blue). See also Figure S3E for additional support, by immunoblot analysis, that yeti is a null allele of Wdr35. See also Figure 4 for preadsorbtion with peptide for demonstration of the specificity of antibody studies.

(I and J) Primary fibroblast cells from a control (I) or WDR35Δ5/Δ5 SRP patient (J) were serum starved for 36–48 hr before costaining with antibodies directed against WDR35 (green, 02 antibody) and γ-tubulin (red). Fainter, nonspecific staining of cytoplasmic microtubules by γ-tubulin is observed in human control and mutant fibroblasts. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue).

(K and L) Wdr35 siRNA knockdown leads to reduced cilia formation. ShhLIGHT II cells were transfected with siRNAs against Wdr35. qRT-PCR shows significantly reduced levels of Wdr35 mRNA after siRNA treatment (K). A 50% reduction in the number of ciliated cells was observed when Wdr35 mRNA was knocked down to 15% of wild-type levels (L). Negative: scramble siRNA; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗p < 0.01 (Chi-squared). Bars represent standard deviations. Statistical significance was determined via a Student's t test.

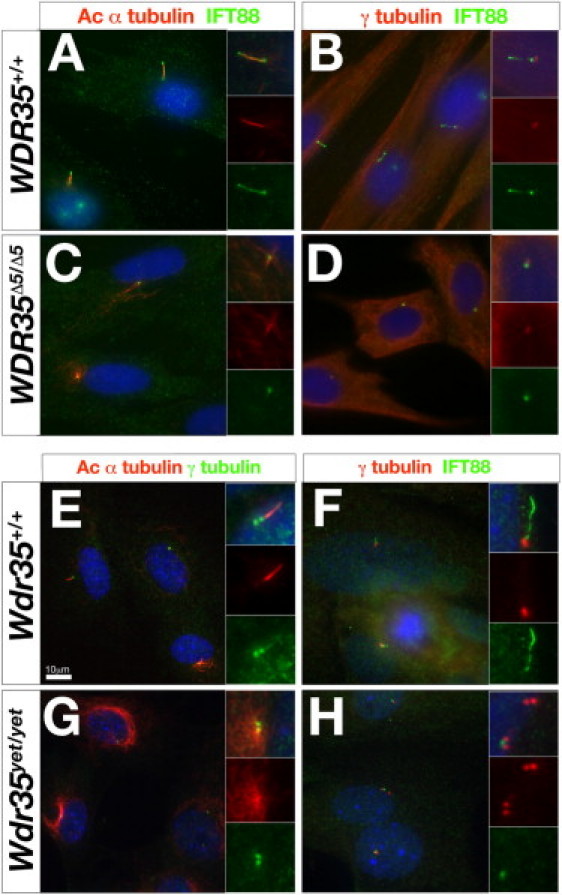

To better characterize the cellular function of WDR35 in primary cilia, we analyzed primary fibroblasts from human (Figures 3A–3D) and mouse (Figures 3E–3K) controls and WDR35 mutants. Cilia axonemes were clearly detectable by acetylated α-tubulin staining, a marker of stabilized microtubules, in human (Figures 3A and 3B) and mouse (Figures 3E and 3F) control cells. However, these structures were completely absent in both human (Figures 3C and 3D) and mouse (Figures 3G and 3H) mutant cells. Instead, extended perinuclear microtubule arrays were prominent via acetylated α-tubulin staining in both human and mouse mutant cells (Figure 3C compared to Figure 3A and Figure 3G compared to Figure 3E). Because loss of retrograde IFT transport results in accumulation of anterograde IFT components in mutant cilia, we examined the localization of complex B protein IFT88 (MIM 600595) in WDR35 mutant fibroblasts. Consistent with a functional role in retrograde IFT trains, some cilia-like structures remained in these mutant cells, as shown by restricted IFT88 accumulations around the γ-tubulin-positive basal bodies (Figures 3D and 3H).

Figure 3.

Wdr35 Is Required for Mammalian Ciliogenesis

(A–D) Primary fibroblast cells from a control (A and B) or WDR35Δ5/Δ5 SRP patient (C and D) were serum starved for 36–48 hr before costaining with antibodies directed against IFT88 (green) and acetylated α-tubulin (red) (A and C) or IFT88 (green) and γ-tubulin (red) (B and D). Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Inserts show higher magnification of individual cilia in merged or single channels.

(E–H) Primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts derived from 11.5 dpc control Wdr35+/+ (E and F) or Wdr35yet/yet mutants (G and H) were cultured and serum starved and then costained with antibodies directed against γ-tubulin (green) and acetylated α-tubulin (red) (E and G) or IFT88 (green) and γ-tubulin (red) (F and H). Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Inserts show high magnification of individual cilia in merged or single channels. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

Clinical distinction between syndromes in the skeletal dysplasia spectrum could result from underlying differences in the degrees of disruption to cilia structure and/or function, as a result of different mutations in the same gene. Mutations in WDR35 were recently identified in a subset of patients with Sensenbrenner syndrome/CED.14 Therefore, we undertook homology modeling of WDR35 mutations on the predicted protein structure to gain additional insight into the molecular genetics underlying the clinical phenotypes (Figure 4). All of the WDR35 missense mutations identified to date in both Sensenbrenner14 and SRP (Figure 4A) affect highly conserved WDR35 residues, suggesting that they are all likely to be pathogenic. However, homology modeling reveals striking differences in the functional consequences of the WDR35 mutations in SRP versus Sensenbrenner syndrome cases. A similar configuration of N-terminal WD40 repeats and C-terminal tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR)-like motifs observed in WDR35 (Figure 1E) is found in other IFT complex A and B proteins.24 The WD40/WD40-like repeats are involved in intracellular trafficking, cargo recognition, and binding.24,25 A similar protein structure is also shared with the coat complexes COPI, COPII, and clathrin, which are involved in vesicle trafficking,24,28 and it was recently shown that in coat proteins, the N-terminal WD40-like β-propeller is essential for vesicular cage formation.29 Taking advantage of the high secondary-structure homology of WDR35 to the structure of yeast β′-COP29, we used structure-prediction algorithms and homology to model the structure of WDR35 (Figure S6). WDR35 is predicted to fold into two seven-bladed β-propellers, each with an offset WD40-like repeat, followed by an extended TPR-containing α-solenoid domain (Figures 4B and 4C). This model highlights the consequences of the human SRP mutations: the WDR35Δ5 mutation results in an in-frame deletion of the third blade in the N-terminal seven-bladed propeller, whereas the SRP-3-1 missense mutation (p.Trp261Arg) changes one of seven highly conserved tryptophan residues at the inner face of the same propeller (Figures 4C and 4D). That both SRP deletion and missense mutations impact the N-terminal β-propeller, which has been implicated in higher-order organization of COPI complexes, suggests that these mutations interrupt key interaction motifs required for IFT-A train assembly or stability, resulting in abrogated retrograde transport. This hypothesis is consistent with the severe ciliogenesis phenotype observed in our SRP human and mouse WDR35 mutants. In contrast, missense mutations identified in the milder Sensenbrenner/CED cases14 are found in more C-terminal domains of WDR35, suggesting that interactions with specific cargo or other IFT components may be affected, resulting in impairment, but not complete inhibition, of retrograde transport.

WDR35 has been recently implicated in Sensenbrenner syndrome/CED and now, through our work, in a clinically distinct syndrome of severe SRP. Our results show that SRP and CED are allelic, demonstrating not only that the SRPs show locus heterogeneity but that clinically distinct ciliopathies with severe and moderate presentation can result from allelic heterogeneity in the same gene. Given the parallels with the null mouse mutants, our current study suggests that the more severe human disease, SRP, is the result of complete loss of function of WDR35, resulting in profound ciliogenesis defects. Furthermore, molecular modeling has shown that SRP mutations affect key structural elements in the N-terminal β-propeller domain, which by homology with the COPI, COPII, and clathrin proteins is involved in higher complex organization of transport modules. Given the broad developmental expression of WDR35 and the multisystem defects observed in both human and mouse mutants, future tissue-specific mutation studies of Wdr35 in mice will be needed to determine which are the primary defects underlying the pleiotropic loss of WDR35. Mutant studies in lower-order model organisms, such as Chlamydomonas and C. elegans, have been very powerful for identifying cilia phenotypes. However, the complexities of mammalian cilia's structure and function, in particular with respect to its role in developmental signaling, emphasize the importance of mouse molecular genetics. The use of mouse models for investigating the role of the IFT machinery and specific cargo will provide further insight into the pathogenesis of ciliopathies and the reasons underlying the variability in clinical presentation.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Pope (Clinical Research Coordinator, MCRI) and the families involved in this research. We thank I. Algianis, E. Maher , and C. Patel for sharing clinical samples for WDR35 screening. We are grateful to P. Perry and M. Pearson for imaging assistance. We thank D. FitzPatrick, A. Jackson, and T. Kunath for critical comments on the manuscript. This work was funded by the Medical Research Council (UK) and the National Health and Medical Research Council Australia (program grant 490037). Support to P.M. was provided by fellowships from the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Caledonian Research Foundation. P.J.L. was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Australia RD Wright Fellowship (334346).

Contributor Information

Pleasantine Mill, Email: pleasantine.mill@hgu.mrc.ac.uk.

Paul J. Lockhart, Email: paul.lockhart@mcri.edu.au.

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

Mouse Genome Informatics, http://www.informatics.jax.org/

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim

References

- 1.Superti-Furga A., Unger S. Nosology and classification of genetic skeletal disorders: 2006 revision. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2007;143:1–18. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker K., Beales P.L. Making sense of cilia in disease: the human ciliopathies. Am. J. Med. Genet. C. Semin. Med. Genet. 2009;151C:281–295. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho N.C., Francomano C.A., van Allen M. Jeune asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy and short-rib polydactyly type III (Verma-Naumoff) are variants of the same disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2000;90:310–314. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(20000214)90:4<310::aid-ajmg9>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amar M.J., Sutphen R., Kousseff B.G. Expanded phenotype of cranioectodermal dysplasia (Sensenbrenner syndrome) Am. J. Med. Genet. 1997;70:349–352. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19970627)70:4<349::aid-ajmg3>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pedersen L.B., Rosenbaum J.L. Intraflagellar transport (IFT) role in ciliary assembly, resorption and signalling. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2008;85:23–61. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00802-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kozminski K.G., Beech P.L., Rosenbaum J.L. The Chlamydomonas kinesin-like protein FLA10 is involved in motility associated with the flagellar membrane. J. Cell Biol. 1995;131:1517–1527. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pazour G.J., Dickert B.L., Witman G.B. The DHC1b (DHC2) isoform of cytoplasmic dynein is required for flagellar assembly. J. Cell Biol. 1999;144:473–481. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.3.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Porter M.E., Bower R., Knott J.A., Byrd P., Dentler W. Cytoplasmic dynein heavy chain 1b is required for flagellar assembly in Chlamydomonas. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1999;10:693–712. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.3.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu A., Wang B., Niswander L.A. Mouse intraflagellar transport proteins regulate both the activator and repressor functions of Gli transcription factors. Development. 2005;132:3103–3111. doi: 10.1242/dev.01894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merrill A.E., Merriman B., Farrington-Rock C., Camacho N., Sebald E.T., Funari V.A., Schibler M.J., Firestein M.H., Cohn Z.A., Priore M.A. Ciliary abnormalities due to defects in the retrograde transport protein DYNC2H1 in short-rib polydactyly syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;84:542–549. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dagoneau N., Goulet M., Geneviève D., Sznajer Y., Martinovic J., Smithson S., Huber C., Baujat G., Flori E., Tecco L. DYNC2H1 mutations cause asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy and short rib-polydactyly syndrome, type III. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;84:706–711. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beales P.L., Bland E., Tobin J.L., Bacchelli C., Tuysuz B., Hill J., Rix S., Pearson C.G., Kai M., Hartley J. IFT80, which encodes a conserved intraflagellar transport protein, is mutated in Jeune asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:727–729. doi: 10.1038/ng2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walczak-Sztulpa J., Eggenschwiler J., Osborn D., Brown D.A., Emma F., Klingenberg C., Hennekam R.C., Torre G., Garshasbi M., Tzschach A. Cranioectodermal Dysplasia, Sensenbrenner syndrome, is a ciliopathy caused by mutations in the IFT122 gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;86:949–956. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilissen C., Arts H.H., Hoischen A., Spruijt L., Mans D.A., Arts P., van Lier B., Steehouwer M., van Reeuwijk J., Kant S.G. Exome sequencing identifies WDR35 variants involved in Sensenbrenner syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;87:418–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shalom O., Shalva N., Altschuler Y., Motro B. The mammalian Nek1 kinase is involved in primary cilium formation. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:1465–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White M.C., Quarmby L.M. The NIMA-family kinase, Nek1 affects the stability of centrosomes and ciliogenesis. BMC Cell Biol. 2008;9:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-9-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Upadhya P., Birkenmeier E.H., Birkenmeier C.S., Barker J.E. Mutations in a NIMA-related kinase gene, Nek1, cause pleiotropic effects including a progressive polycystic kidney disease in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:217–221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thiel C., Kessler K., Giessl A., Dimmler A., Shalev S.A., von der Haar S., Zenker M., Zahnleiter D., Stöss H., Beinder E. NEK1 mutations cause short-rib polydactyly syndrome type majewski. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;88:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cortellino S., Wang C., Wang B., Bassi M.R., Caretti E., Champeval D., Calmont A., Jarnik M., Burch J., Zaret K.S. Defective ciliogenesis, embryonic lethality and severe impairment of the Sonic Hedgehog pathway caused by inactivation of the mouse complex A intraflagellar transport gene Ift122/Wdr10, partially overlapping with the DNA repair gene Med1/Mbd4. Dev. Biol. 2009;325:225–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huangfu D., Anderson K.V. Cilia and Hedgehog responsiveness in the mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:11325–11330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505328102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.May S.R., Ashique A.M., Karlen M., Wang B., Shen Y., Zarbalis K., Reiter J., Ericson J., Peterson A.S. Loss of the retrograde motor for IFT disrupts localization of Smo to cilia and prevents the expression of both activator and repressor functions of Gli. Dev. Biol. 2005;287:378–389. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qin J., Lin Y., Norman R.X., Ko H.W., Eggenschwiler J.T. Intraflagellar transport protein 122 antagonizes Sonic Hedgehog signaling and controls ciliary localization of pathway components. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:1456–1461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011410108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kannu P., McFarlane J.H., Savarirayan R., Aftimos S. An unclassifiable short rib-polydactyly syndrome with acromesomelic hypomineralization and campomelia in siblings. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2007;143A:2607–2611. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Avidor-Reiss T., Maer A.M., Koundakjian E., Polyanovsky A., Keil T., Subramaniam S., Zuker C.S. Decoding cilia function: defining specialized genes required for compartmentalized cilia biogenesis. Cell. 2004;117:527–539. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00412-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cole D.G. The intraflagellar transport machinery of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Traffic. 2003;4:435–442. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.t01-1-00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukhopadhyay S., Wen X., Chih B., Nelson C.D., Lane W.S., Scales S.J., Jackson P.K. TULP3 bridges the IFT-A complex and membrane phosphoinositides to promote trafficking of G protein-coupled receptors into primary cilia. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2180–2193. doi: 10.1101/gad.1966210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blacque O.E., Li C., Inglis P.N., Esmail M.A., Ou G., Mah A.K., Baillie D.L., Scholey J.M., Leroux M.R. The WD repeat-containing protein IFTA-1 is required for retrograde intraflagellar transport. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:5053–5062. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-06-0571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jékely G., Arendt D. Evolution of intraflagellar transport from coated vesicles and autogenous origin of the eukaryotic cilium. Bioessays. 2006;28:191–198. doi: 10.1002/bies.20369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee C., Goldberg J. Structure of coatomer cage proteins and the relationship among COPI, COPII, and clathrin vesicle coats. Cell. 2010;142:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.