Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

The aim of the study was to investigate the effects of genetic deficiency of aldose reductase in mice on the development of key endpoints of diabetic nephropathy.

Methods

A line of Ar (also known as Akr1b3)-knockout (KO) mice, a line of Ar-bitransgenic mice and control C57BL/6 mice were used in the study. The KO and bitransgenic mice were deficient for Ar in the renal glomeruli and all other tissues, with the exception of, in the bitransgenic mice, a human AR cDNA knockin-transgene that directed collecting-tubule epithelial-cell-specific AR expression. Diabetes was induced in 8-week-old male mice with streptozotocin. Mice were further maintained for 17 weeks then killed. A number of serum and urinary variables were determined for these 25-week-old mice. Periodic acid–Schiff staining, western blots, immunohistochemistry and protein kinase C (PKC) activity assays were performed for histological analyses, and to determine the levels of collagen IV and TGF-β1 and PKC activities in renal cortical tissues.

Results

Diabetes-induced extracellular matrix accumulation and collagen IV overproduction were completely prevented in diabetic Ar-KO and bitransgenic mice. Ar deficiency also completely or partially prevented diabetes-induced activation of renal cortical PKC, TGF-β1 and glomerular hypertrophy. Loss of Ar results in a 43% reduction in urine albumin excretion in the diabetic Ar-KO mice and a 48% reduction in the diabetic bitransgenic mice (p < 0.01).

Conclusions/interpretation

Genetic deficiency of Ar significantly ameliorated development of key endpoints linked with early diabetic nephropathy in vivo. Robust and specific inhibition of aldose reductase might be an effective strategy for the prevention and treatment of diabetic nephropathy.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00125-011-2045-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorised users.

Keywords: Aldose reductase, Collagen IV, Diabetic nephropathy, Oxidative stress, PKC, Polyol pathway, TGF-β1, Urinary albumin

Introduction

In the mammalian kidneys, aldose reductase (AR) is abundantly produced in the inner medulla, where it converts glucose to sorbitol, the latter serves as a critical organic osmolyte to protect the collecting duct tubule cells from hyperosmotic insults [1] (the human gene encoding AR is AKR1B1 [also known as AR] and the mouse gene is Akr1b3 [also known as Ar]). In contrast to its prominent expression in the renal medulla, AR production in the renal cortex is low to moderate, depending on cell types. Under normal physiological conditions, AR production in the glomerulus is low. However, a significant increase in glomerular AR production was found in diabetic human patients [2, 3]. Diabetes in rats led to a tenfold increase in glomerular sorbitol content, whereas sorbitol was unchanged in diabetic rats treated with an aldose reductase inhibitor (ARI), sorbinil [4]. Within the glomerulus, Ar mRNA expression is strongly induced in the mesangial cells [5, 6] and the endothelial cells [7] under hypertonic conditions. Overactivation of AR in renal cells has been linked with aberrant activation of protein kinase C (PKC) [8–10], generation of advanced glycation products, increased expression of TGF-β and generation of reactive oxygen species [11]. Together these data suggest that significant activation of AR by hyperglycaemia in the renal glomeruli might contribute to the onset or progression of glomerulopathy and diabetic nephropathy (DN).

AR is the first and the rate-limiting enzyme of the polyol pathway, a pathway that has been implicated in the development of diabetic complications, particularly diabetic retinopathy and diabetic neuropathy [11, 12]. The association of AR and the polyol pathway with the development of DN, however, is less conclusive, partly because the data obtained from genetic, biochemical, pharmacological, animal and clinical studies have been less consistent [13]. For instance, some human genetic studies support the association of AR 5′-end polymorphism with DN [14–19] while others did not confirm this [19–21]. In one animal model study, transgenic overexpression of human AR in mice led to pathological changes in the kidney, lens and retina [22]. In another communication, however, it was reported that diabetes-induced albuminuria was prevented in transgenic rats overexpressing human AR selectively in the straight (S3) portion of renal proximal tubules [23]. Most pharmacological experiments demonstrated a positive influence of chemically synthesised ARIs on the development of DN in diabetic rats [13, 24–26], but a few failed [27, 28]. Further, although some human clinical trials have reported unchanged glomerular function after ARI treatment [29], encouraging results have also been obtained that clearly demonstrate the beneficial effects of the inhibition of AR with ARIs [13, 30].

The reasons for the inconsistency with regard to the pathophysiological roles of AR and the effectiveness of ARIs in DN are not completely clear. However, incomplete AR inhibition, the presence of multiple AR-like proteins, individual genetic differences and the specificity, side or toxic effects of ARIs are among the possible contributing factors. Studies have shown that human and rodent kidney tissues possess a number of AR-like proteins, such as AR-like gene-1 [31] and renal-specific oxidoreductase [32], as well as renal aldehyde reductases [33]. It is not clear how these structurally and functionally similar proteins might interact in vitro and in vivo. Meanwhile, the specificity of these inhibitors used in animal studies or clinical studies remains open to question. Some of them are already known to be able to inhibit aldehyde reductases, in addition to AR [33]. Such ‘off-target’ effects might underlie undesired side effects or even toxic effects.

One approach to overcome the shortcomings associated with the use of ARIs is to use a gene-knockout (KO) model. Mice globally deficient in Ar (Ar −/−), however, were found to carry defects in the renal medulla characterised by renal medullary atrophy and epithelial cell death [34, 35]. As a consequence of these medullary lesions, Ar-deficient mice develop a phenotype resembling that of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus in human [34, 35]. Because of this problem, no DN study has yet been performed with Ar-deficient mice, even though they have been available for more than 10 years [34, 36]; therefore, the data from a gene-knockout model have been lacking. Recently, we created a double-transgenic mouse line (Ar −/− KspAR +/− bitransgenic [BT]) that is deficient in AR in all tissues and the kidney glomeruli except in the inner medulla, where an AR-knockin transgene is driven by the kidney-specific cadherin promoter to direct AR expression specifically in the collecting tubule epithelial cells [35]. The BT mice differ from the Ar-KO mice in that the Ar-KO mice are completely deficient in AR whereas the BT mice are deficient in AR in all tissues, including most parts of the kidney, except the medullary collecting tubule epithelial cells that carry the knockin transgene. The glomeruli from the Ar-KO and BT mice, however, are equivalent in terms of AR production. As a consequence of the medullary epithelial cell-specific AR expression of the knockin transgene, the cellular lesions in renal medulla and the urine concentrating mechanisms were shown to be significantly corrected in the BT mice [35]. In our current study, we used the Ar-KO and BT mice to investigate the effects of genetic deficiency of Ar on the development of early DN. Our results indicate that genetic ablation of Ar significantly ameliorates the development of DN in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic C57BL/6 mice.

Methods

Animals and animal treatments

All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Xiamen University Institutional Committee for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Ar −/− mice [34] were prepared and backcrossed with C57BL/6 mice for seven generations. A line of transgenic mice (KspAR +/−) in which a human AR transgene driven by the mouse kidney-specific cadherin promoter to overproduce AR specifically in the collecting tubule epithelial cells was generated and backcrossed with C57BL/6 mice for six generations as described [35]. Subsequent intercrosses between the KO mice and the KspAR +/− mice generated the BT mice heterozygous for KspAR and homozygous for the Ar-KO allele (Ar −/− KspAR +/−), as well as the Ar-KO mice and the wild-type (WT) mice [35]. The genotypes of three groups of mice were verified as described previously by Yang et al. [35]. The KO, BT and WT mice were, therefore, relatively homogeneous for the C57BL/6 background that was maintained as described previously [35]. For each particular genotype, male mice, 8 weeks old, were randomly divided into two subgroups (each having at least six mice): one was intraperitoneally injected with 40 mg kg−1 day−1 for five consecutive days; and the other was injected with a vehicle solution (0.1 mol/l citrate buffer [Cit]). Immediately after the diabetic induction, blood glucose was assayed with a Glucometer (OneTouch Ultra, LifeScan, Milpitas, CA, USA) and only those mice with blood glucose levels above 16 mmol/l were considered to be diabetic. Six treatment groups of mice were therefore generated. They were: non-diabetic WT (WT + Cit) mice; non-diabetic KO (KO + Cit) mice; non-diabetic BT (BT + Cit) mice; diabetic WT (WT + STZ) mice; diabetic KO (KO + STZ) mice; and diabetic BT (BT + STZ) mice. The diabetic and non-diabetic mice were maintained for an additional 17 weeks. The animals were transferred to metabolism cages 1 day before the age of 25 weeks (one mouse/cage, with free access to standard chow diet and water) for 24 h for urine sample collection. Blood samples were collected by sinus puncture and the animals were subsequently killed and kidneys were dissected for analyses.

PKC activity assays

PKC activity assays were carried out with the PepTag Nonradioactive PKC Assay System from Promega (Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, renal cortical tissues were homogenised in 2 ml ice-cold extraction buffer (supplied) with a Kinematica homogeniser (Lucerne, Switzerland). The homogenates were centrifuged at 100,000×g and 4°C for 60 min. The supernatant fractions were taken as the cytosol fractions whereas the pellets were further dissolved in 2 ml of the extraction buffer with 1% Triton X-100. After 30 min incubation at 4°C, the solutions were centrifuged again at 100,000×g for 60 min, and the second supernatant fractions were used as the membrane fractions. The concentrations of protein in the preparations were determined with the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA). The membrane and cytoplasmic fractions were then used for PKC activity assays, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated reaction mixtures were separated on a 0.8% agarose gel. The gels were visualised under UV light and the bands were quantified by densitometric analysis using Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Shanghai, China).

Serum analyses, urine analyses, western blots for TGF-β1 and collagen IV, immunohistochemistry for renal expression of collagen IV and other renal histological analyses

These experimental procedures are described in detail in the Electronic supplementary material (ESM).

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed with the GraphPad Prism. Values are expressed as the means ± SEM. Multiple group comparisons were performed with one-way ANOVA with the Bonferroni’s post test and pair-wise comparisons were performed with unpaired Student’s t test. A probability value <0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

AR deficiency in the Ar-KO and BT mice significantly ameliorated diabetes-induced renal hypertrophy, elevations in serum triacylglycerols and serum LDL-cholesterol and urinary albumin excretion (UAE)

To assess the effects of genetic deficiency of Ar on the development of DN, we treated the Ar-KO, BT and WT C57BL/6 mice with multiple low doses of STZ (40 mg/kg, i.p. for five consecutive days) to destroy the mouse pancreatic beta cells and to induce diabetes. After STZ injection, blood glucose levels were determined and only those with blood glucose levels greater than or equal to 16 mmol/l were considered to be diabetic. Both the STZ-treated mice and the control mice were further maintained for 17 weeks under normal rearing conditions (free access to standard chow and water) to allow the development of diabetic kidney diseases.

At the age of 25 weeks (17 weeks from diabetes onset), diabetic WT mice exhibited typical pathophysiological features of early DN (Table 1). With the exception of serum HDL-cholesterol, the body weight, serum content of triacylglycerol, total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), GFR and UAE were all significantly altered in diabetic WT mice, manifesting as the development of diabetes or early DN. In the diabetic Ar-KO mice, complete deficiency of AR appeared to result in significant improvement in the ratio of kidney/body weight (6.80 ± 0.52 for diabetic Ar-KO mice vs 8.20 ± 0.45 for diabetic WT mice, p < 0.05), serum triacylglycerols (0.57 ± 0.07 mmol/l for diabetic Ar-KO mice vs 1.11 ± 0.18 mmol/l for diabetic WT mice, p < 0.001), serum LDL-cholesterol (1.16 ± 0.13 mmol/l for diabetic Ar-KO mice vs 1.62 ± 0.13 mmol/l for diabetic WT mice, p < 0.05) and UAE (1.49 ± 0.26 μg/mg creatinine for diabetic Ar-KO mice vs 2.62 ± 0.34 μg/mg creatinine for diabetic WT mice, p < 0.001). In contrast to these DN-associated variables, the BUN and GFR were not significantly improved in the diabetic Ar-KO mice. However, in diabetic BT mice, not only the body weight, but the ratio of kidney/body weight, serum triacylglycerols and LDL-cholesterol, and UAE were all significantly improved compared with the diabetic WT mice; BUN (6.28 ± 0.19 mmol/l for diabetic BT mice vs 8.75 ± 0.53 mmol/l for diabetic WT mice, p < 0.001) and GFR (0.18 ± 0.01 l/24 h for diabetic BT mice vs 0.12 ± 0.01 l/24 h for diabetic WT mice, p < 0.05) both also appeared to be significantly improved. In the STZ-treated groups, the three genotypes of diabetic mice all excreted large volumes of urine that were not statistically different. As these volumes of urine were much larger than those in AR-deficiency-induced polyuria, it suggests that hyperglycaemia is the predominant contributing factor for the polyuric phenotype. Together, these biochemical analyses indicate that AR deficiency resulted in improvement of most serum and urinary variables associated with DN in diabetic C57BL/6 mice.

Table 1.

Physiological variables of the six mouse groups at the age of 25 weeks

| Variable | Treatment groups | p values | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-diabetic WT + Cit | Non-diabetic KO + Cit | Non-diabetic BT + Cit | Diabetic WT + STZ | Diabetic KO + STZ | Diabetic BT + STZ | WT + STZ vs WT + Cit | KO + STZ vs WT + STZ | BT + STZ vs WT + STZ | |

| Body weight (g) | 30.98 ± 0.93 | 29.88 ± 1.52 | 29.87 ± 1.06 | 22.48 ± 1.03 | 21.88 ± 1.74 | 26.65 ± 0.72 | <0.001 | NS | <0.05 |

| Kidney weight/body weight (×103) | 4.94 ± 0.13 | 4.47 ± 0.11 | 5.00 ± 0.08 | 8.20 ± 0.45 | 6.80 ± 0.52 | 6.82 ± 0.28 | <0.001 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| Serum glucose (mmol/l) | 7.72 ± 0.65 | 8.12 ± 0.48 | 8.32 ± 0.27 | 35.37 ± 0.63 | 32.47 ± 2.12 | 26.27 ± 0.87 | <0.001 | NS | <0.001 |

| Serum triacylglycerols (mmol/l) | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 0.52 ± 0.03 | 0.48 ± 0.01 | 1.11 ± 0.18 | 0.57 ± 0.07 | 0.64 ± 0.08 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.01 |

| Serum cholesterol (mmol/l) | 2.65 ± 0.11 | 2.82 ± 0.13 | 2.37 ± 0.10 | 3.60 ± 0.18 | 3.69 ± 0.32 | 3.03 ± 0.11 | <0.01 | NS | NS |

| Serum LDL-cholesterol (mmol/l) | 0.78 ± 0.11 | 0.70 ± 0.09 | 0.64 ± 0.07 | 1.62 ± 0.13 | 1.16 ± 0.13 | 0.92 ± 0.11 | <0.001 | <0.05 | <0.001 |

| Serum HDL-cholesterol (mmol/l) | 1.53 ± 0.06 | 1.76 ± 0.14 | 1.43 ± 0.06 | 1.56 ± 0.26 | 1.60 ± 0.11 | 1.69 ± 0.09 | NS | NS | NS |

| BUN (mmol/l) | 5.55 ± 0.18 | 4.37 ± 0.25 | 5.08 ± 0.28 | 8.75 ± 0.53 | 8.72 ± 0.34 | 6.28 ± 0.19 | <0.001 | NS | <0.001 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/l) | 19.66 ± 0.67 | 17.31 ± 1.95 | 21.13 ± 2.05 | 57.21 ± 6.15 | 66.13 ± 7.13 | 63.85 ± 5.44 | <0.001 | NS | NS |

| Urine volume (ml/day) | 1.25 ± 0.14 | 2.16 ± 0.12 | 1.60 ± 0.09 | 13.77 ± 1.23 | 13.40 ± 2.89 | 16.07 ± 1.78 | <0.001 | NS | NS |

| GFR (l/24 h) | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | <0.05 | NS | <0.05 |

| UAE (μg/mg creatinine) | 0.41 ± 0.04 | 1.02 ± 0.06a | 0.31 ± 0.04b | 2.62 ± 0.34 | 1.49 ± 0.26 | 1.36 ± 0.12 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Data are mean ± SEM, n = 5–6

The UAE differences among the non-diabetic mice appeared to be consistent with the structural and histomorphological improvement in renal medulla in the BT mice under normal physiological conditions [35]

aUAE value in the KO + Cit mice is higher than that in the WT + Cit mice but the difference is not statistically significant (p > 0.05)

bUAE in the BT + Cit mice is significantly lower than that in the KO + Cit mice (p < 0.05) but not significantly different from that in the WT + Cit mice (p > 0.05)

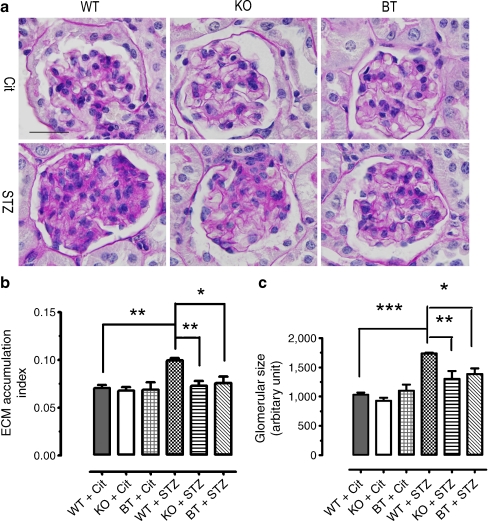

AR deficiency in the diabetic Ar-KO and BT mice significantly ameliorated diabetes-induced glomerular hypertrophy, cell proliferation, mesangial expansion and collagen IV expression

To examine for potential renal cortical morphological differences in the diabetic WT mice and the AR-deficient diabetic mice, we performed periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining with the renal cortical tissues dissected from six treatment groups of mice at the age of 25 weeks. As shown in Fig. 1a, no apparent difference in glomerular morphology was observed for three non-diabetic genotype groups of mice. The glomeruli were of normal size and configuration for non-diabetic WT, Ar-KO and BT mice. Further, there was no sign of mesangial matrix expansion, inflammation or sclerosis in these mice. In contrast to the findings in these non-diabetic mice, very significant glomerular hypertrophy, increased cellularity and narrowing of capillary lumens was observed in the cortex/glomeruli of diabetic WT mice (Fig. 1a). Further, the mesangium was diffusively and markedly expanded with PAS-positive (purple colour) matrix material. When the digital images of about 30 glomeruli for each genotype were quantitatively analysed, the extracellular matrix (ECM) accumulation index for the diabetic WT mice was, on average, 41% higher than that for the non-diabetic WT mice (0.099 ± 0.002 for diabetic WT vs 0.070 ± 0.003 for non-diabetic WT, p < 0.01, Fig. 1b), whereas the glomerular size for the diabetic WT on average was 68% higher than that for the non-diabetic WT mice (1,733 ± 13.9 for diabetic WT vs 1,031 ± 36.7 for non-diabetic WT, p < 0.001, Fig. 1c). These results indicate significant lesions in renal cortical/glomerular structures in the WT diabetic mice at the age of 25 weeks. Interestingly, in the glomeruli of diabetic Ar-KO and BT mice, diabetes-induced glomerular hypertrophy, cell proliferation and mesangial matrix expansion were all significantly corrected (Fig. 1a–c). Despite the exposure to hyperglycaemia for 17 weeks, glomerular size and ECM accumulation and configuration in the diabetic Ar-KO and BT mice were almost indistinguishable from those in the non-diabetic mice, characterised by improved glomerular hypertrophy, reduced cellularity and normalisation of mesangial expansion (Fig. 1a–c). These results indicated significant restoration in the renal cortical/glomerular structures as a consequence of genetic deficiency of Ar.

Fig. 1.

The effects of genetic deficiency of Ar on the pathohistological development of DN in the renal cortex and glomerulus as determined by PAS staining. a Renal cortex and glomerulus morphology in six treatment groups of mice at the age of 25 weeks as determined by PAS staining. The results were typical of three mice for each treatment group. Original magnification ×1,000; scale bar, 25 μm. b Quantitative analyses of ECM accumulation index in six treatment groups of mice. Values were expressed as the mean ± SEM, n = 3; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. c Quantitative analyses of glomerular sizes in six treatment groups of mice. Glomerular area was determined as described in the Methods. Values are expressed as the mean ± SEM, n = 3; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

In contrast to the significant differences in the cortex/glomeruli areas, the outer medullary areas did not show apparent histomorphological differences among genotype groups of mice as determined by PAS staining (ESM Fig. 1). In the inner medulla, however, severe tubular atrophy was observed for all three genotype groups of diabetic mice. The tubulointerstial lesions in the diabetic BT mice, however, appeared to be slightly improved (ESM Fig. 2) as compared with the diabetic Ar-KO mice.

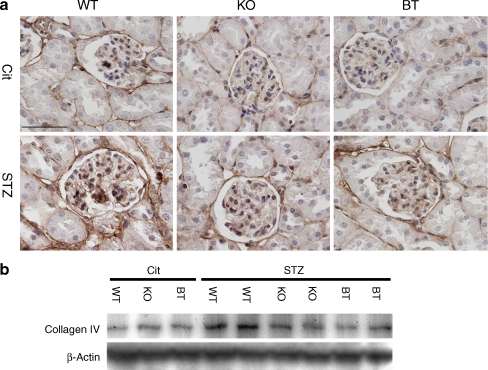

As collagen IV is the principal protein of the expanded ECM in the diabetic renal glomeruli [37, 38], we analysed the production of collagen IV by immunohistochemistry and western blot. As shown in Fig. 2, in non-diabetic WT mice, relatively low collagen IV production was found in the mesangial cells, the Bowman’s capsule and the tubule basement membranes. In strong contrast to this, very prominent collagen IV production was found in the cortical tissues of the diabetic WT mice in both the intraglomerular cells and extraglomerular cells. In Ar-deficient mice, however, renal cortical collagen IV production was significantly reduced in both the Ar-KO and BT mice, with the reduction in the glomerular expression being more apparent (Fig. 2a). Western blots of renal cortical tissues further verified the trends of collagen production in diabetic WT, Ar-KO and BT mice (Fig. 2b), suggesting that AR deficiency, in glomeruli in particular, led to significant reductions in diabetes-induced overproduction of collagen IV in the glomeruli.

Fig. 2.

Collagen IV production in the renal cortex and glomerulus in six treatment groups of mice at the age of 25 weeks. a Collagen IV production in renal cortex and glomerulus in six treatment groups of mice as determined by immunohistochemistry. Original magnification ×1,000; scale bar, 50 μm. The results were typical of three mice for each treatment group. b Collagen IV production in renal cortex in six treatment groups of mice as determined by western blots. Each lane represents an independent sample. Protein loading was calibrated using β-actin

AR deficiency appears to slightly ameliorate diabetes-induced oxidative stress in the renal cortex

Recent studies suggest that DN might be closely linked to oxidative stress [39, 40] and that overactivation of AR/polyol pathway contributes significantly to hyperglycaemia-induced oxidative/nitrosative stress [41, 42]. We therefore performed assays to determine glutathione (GSH) and malondialdehyde (MDA) content and the superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity for renal cortical tissues (n = 3 per group) in the six study groups of mice (ESM Fig. 3). When the data for all six treatment groups of mice were analysed with one-way ANOVA, no significant difference in GSH or MDA content or SOD activity between genotype groups was observed for either non-diabetic or diabetic mice, which is probably largely because of the limited number of mice. Despite this, pair-wise comparisons showed that the renal cortical GSH was depleted by ~68% in WT + STZ mice vs WT + Cit mice (p < 0.05, Student’s t test), manifesting as a significant depletion in GSH consistent with hyperglycaemia-induced oxidative stress. Interestingly, GSH appeared to be partially corrected to ~72% and ~65% of the normal level in the diabetic Ar-KO and BT groups, respectively, although the results with n = 3 per group were not statistically significant. An apparent rise in cortical MDA content in the diabetic cortex, also consistent with excess oxidative stress in the diabetic vs non-diabetic cortex, was also seen in WT + STZ mice vs WT + Cit mice, and an apparent correction was seen in the diabetic Ar-KO mice but not in the diabetic BT mice. In contrast to GSH and MDA, SOD activity showed no trend towards change in any of the groups. Together these data are, in general, consistent with the presence of oxidative stress in the renal cortex of the diabetic vs the non-diabetic state, with a corrective effect of AR deficiency on hyperglycaemia-induced oxidative stress.

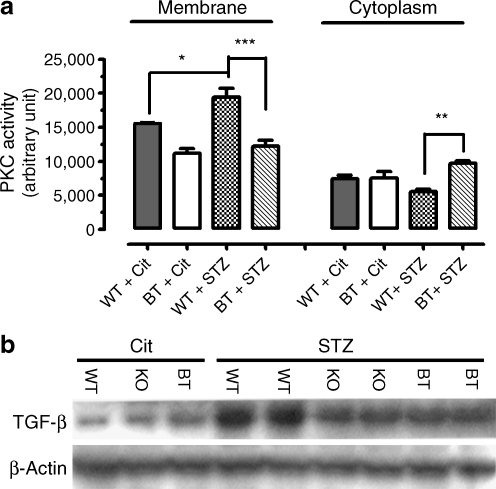

AR deficiency in the diabetic KO and BT mice caused significant alterations in PKC activity and TGF-β1 production in the renal cortex

Previous studies have established that the overactivation of PKC and TGF-β1 plays an important role in the development of DN. Among other roles, the PKC–TGF-β1 axis is involved in renal fibrogenesis by regulating the production of a number of components for mesangial expansion. To find out how the genetic deficiency of Ar might affect PKC, we determined PKC activity in the cytosolic and membrane fractions of renal cortical homogenates from four treatment groups of mice (i.e. non-diabetic WT and BT mice and diabetic WT and BT mice). As shown in Fig. 3a, 17 weeks of diabetes caused a 24.8% elevation in the renal cortical membrane PKC activity in the BT mice (19,446 ± 1,311 for diabetic WT mice vs 15,572 ± 144 for non-diabetic WT mice, p < 0.05), whereas the cytosolic PKC activity was reduced by about 25%, although this was not statistically significant. In Ar-deficient BT mice, however, the diabetes-induced elevation of membrane PKC and downregulation of cytosolic PKC were largely reversed. For the membrane PKC, Ar deficiency caused a 37% reduction (19,446 ± 1,311 for diabetic WT mice vs 12,189 ± 918 for diabetic BT mice, p < 0.001). For cytosolic PKC, Ar deficiency caused a 75% increase (5,534 ± 366 for diabetic WT mice vs 9,685 ± 341 for diabetic BT mice, p < 0.01). Together these results indicate that genetic Ar deficiency significantly affected renal cortical PKC activity.

Fig. 3.

Effects of Ar genetic deficiency on PKC activity and the production of TGF-β1. a Membrane and cytosolic PKC activities in the renal cortex of four treatment groups of mice at the age of 25 weeks. Values were expressed as the mean ± SEM, n = 3; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. b TGF-β1 production in the renal cortex in six treatment groups of mice at the age of 25 weeks as determined by western blots. Each lane represents an independent sample. Protein loading was calibrated using β-actin

We further performed western blots to analyse renal cortical TGF-β1 production in non-diabetic and diabetic mice. As shown in Fig. 3b, moderate levels of TGF-β1 protein were detected in non-diabetic WT, KO and BT mice. Seventeen weeks of diabetes, however, greatly upregulated renal cortical TGF-β1 production in the diabetic WT mice. In contrast, in both the diabetic Ar-KO and BT mice, TGF-β1 production was significantly reduced and the reduction of TGF-β1 production is consistent with reduced collagen IV expression in the AR-deficient mice. These data thus suggest that Ar deficiency contributes significantly to the amelioration in the development of DN in the diabetic Ar-KO and BT mice in part through suppressing diabetes-induced activation of TGF-β1.

Discussion

As mentioned earlier, a large body of animal and clinical studies using chemically synthesised ARIs has yielded mixed results. As the use of genetic knockout models might avoid the potential problems associated with the incomplete AR inhibition, non-specific inhibition or other side effects of ARIs, these models are crucial for the more definitive elucidation of the role of AR in DN and of the potential utility of AR inhibition in the prevention or treatment of DN. Consistent with the positive findings of studies using ARIs [13, 24, 25, 43–46], we showed in our current study that the genetic deficiency of Ar in both the diabetic KO mice and the diabetic BT mice resulted in significantly reduced UAE, mesangial matrix expansion and reduced overexpression of collagen IV, and improved glomerular hypertrophy. Further, consistent with previous observations [10, 44], we demonstrated that Ar deficiency was associated with significant attenuation in renal cortical PKC activity and TGF-β1 production. In addition, Ar deficiency significantly ameliorated diabetes-induced renal hypertrophy and elevations in serum triacylglycerols and serum LDL-cholesterol. Together these data clearly imply that hyperglycaemia-induced overactivation of AR and elevation in metabolic flux through the polyol pathway in the renal cortex and the glomeruli contributes significantly to the development of early DN and that inhibition of AR or blockade of the polyol pathway in the renal cortex or the glomeruli might be an effective approach for the prevention or treatment of DN.

Although Ar deficiency resulted in ameliorations in a number of important variables associated with DN in both the diabetic Ar-KO and diabetic BT mice, there were a few variables (including serum glucose, BUN and GFR) that characteristically distinguished the diabetic BT mice from the diabetic Ar-KO mice. Somewhat surprisingly, the level of BUN in diabetic Ar-KO mice at the age of 25 weeks was indistinguishable from that of the diabetic WT mice. In diabetic BT mice, however, BUN was 77% normalised (6.28 ± 0.19 mmol/l for diabetic BT vs 8.75 ± 0.53 mmol/l for diabetic WT, p < 0.001), suggesting much improved glomerular function for the diabetic BT mice. The reasons for these differences between the diabetic Ar-KO mice and the diabetic BT mice are not clear but are probably linked to the corrections in Ar-deficiency-induced renal medullary defects brought about by the re-introduction of renal collecting tubule epithelial-specific production of AR.

PKC signalling has been shown to play critical regulatory roles in the development of DN in experimental models [8]. Because excessive metabolic flux through AR and the polyol pathway is associated with elevation of cytoplasmic NADH/NAD+ and diacylglycerol, the latter being a second messenger for PKC, overactivation of AR has been linked with abnormal activation of PKC [9, 11, 47]. Keogh et al. have reported that AR inhibition prevented glucose-induced prostaglandin synthesis and PKC activation [47]. Using the ARI epalrestat, Ishii et al. have also demonstrated that inhibition of AR blocked glucose-induced increases in PKC and TGF-β1 activity in cultured human mesangial cells [10]. Our demonstration that genetic deficiency of Ar led to a decrease in membrane PKC activity but an increase in the cytosolic PKC is consistent with the results from AR inhibition by ARIs. While the mechanisms for the membrane–cytoplasm redistribution of PKC require further investigation, there now remains no doubt that inhibition of AR is a way to suppress glucose-induced overactivation of PKC in the kidneys.

TGF-β1 is a multifunctional cytokine capable of regulating cell proliferation, differentiation, motility, apoptosis, immune cell function and ECM formation. Currently, this pro-sclerotic protein is recognised as the major cytokine responsible for mesangial expansion, ECM accumulation and vascular dysfunction and glomerulosclerosis in DN [48, 49]. Previous studies have shown that glucose-induced TGF-β1 is polyol pathway dependent [10, 50] and that inhibition of AR leads to suppressed production of TGF-β [10] and collagen IV [44] and reduced mesangial expansion [45]. The suppression of renal cortical TGF-β, collagen IV and mesangial expansion brought about by ARIs is now further recapitulated with the genetic mouse models deficient in Ar in our current investigation. Normalisation of TGF-β1 activity due to AR deficiency thus is likely to contribute significantly to the amelioration of DN in the Ar-KO and BT mice.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Histomorphology of renal outer medulla/cortex junction areas in six treatment groups of mice at the age of 25 weeks, as determined by PAS staining. PAS staining was performed as described. The results were typical of three mice for each treatment group. Original magnification ×1,000. In contrast to the significant differences in the cortex/glomeruli areas, the outer medullary areas did not shown apparent histomorphological differences among genotype groups of mice or between the non-diabetic and diabetic mice (PDF 1.23 mb)

Histomorphology of renal inner medulla in six treatment groups of mice at the age of 25 weeks as determined by PAS staining. PAS staining was performed as described. The results were typical of three mice for each treatment group. Original magnification, ×1,000. Among the Cit-injected non-diabetic mice, the Ar-KO mice showed more compacted and moderately disorganised medullary structures and PAS-positive staining (dark purple), indicative of medullary atrophy/shrinkage and fibrosis. These defects to a certain degree were improved in the Cit-injected BT mice. In comparison with the non-diabetic mice, severe tubular atrophy (yellow arrows indicated) was observed in the inner medullary areas for all three diabetic mouse groups. The tubulointerstitial lesions in the diabetic BT mice, however, appeared to be slightly improved (less tubular atrophy and less PAS staining) compared with that of the diabetic KO mice. These PAS staining results were further confirmed by the haematoxylin and eosin staining (data not included) (PDF 1.10 mb)

Renal cortical content of reduced GSH and MDA, and renal cortical activity of SOD in six treatment groups of mice at the age of 25 weeks. GSH was measured using a commercial kit from Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. MDA was assayed with a commercial kit from Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, following the manufacturer’s instructions. SOD levels were measured using commercial kits from Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, following the manufacturer’s instructions. a Renal cortical content of GSH in six treatment groups of mice (n = 3); *p < 0.05 (Student’s t test). b Renal cortical content of GSH in six treatment groups of mice (n = 3). c Renal cortical activity of SOD in six treatment groups of mice (n = 3) (PDF 79.8 kb)

(PDF 73.0 kb)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Science Foundation of China (#30770490); the 973 Program of China (#2009CB941601); the Science Planning Program of Fujian Province (#2009J1010) and the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (#2009J01180) and the Fujian Provincial Department of Science and Technology (#2010L0002).

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- AR

Aldose reductase

- ARI

Aldose reductase inhibitor

- BT

AR −/− KspAR +/− bitransgenic

- BUN

Blood urea nitrogen

- Cit

Citrate buffer

- DN

Diabetic nephropathy

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- GSH

Glutathione

- KO

Knockout

- MDA

Malondialdehyde

- PAS

Periodic acid–Schiff

- PKC

Protein kinase C

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- STZ

Streptozotocin

- UAE

Urinary albumin excretion

- WT

Wild type

Footnotes

H. Liu, Y. Luo and T. Zhang contributed equally to this study.

References

- 1.Burg MB, Kador PF. Sorbitol, osmoregulation, and the complications of diabetes. J Clin Invest. 1988;81:635–640. doi: 10.1172/JCI113366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corder CN, Braughler JM, Culp PA. Quantitative histochemistry of the sorbitol pathway in glomeruli and small arteries of human diabetic kidney. Folia Histochem Cytochem. 1979;17:137–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasajima H, Yamagishi S, Sugai S, Yagihashi N, Yagihashi S. Enhanced in situ expression of aldose reductase in peripheral nerve and renal glomeruli in diabetic patients. Virchows Arch. 2001;439:46–54. doi: 10.1007/s004280100444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beyer-Mears A, Ku L, Cohen MP. Glomerular polyol accumulation in diabetes and its prevention by oral sorbinil. Diabetes. 1984;33:604–607. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.33.6.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaneko M, Carper D, Nishimura C, Millen J, Bock M, Hohman TC. Induction of aldose reductase expression in rat kidney mesangial cells and Chinese hamster ovary cells under hypertonic conditions. Exp Cell Res. 1990;188:135–140. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(90)90288-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kikkawa R, Umemura K, Haneda M, et al. Identification and characterization of aldose reductase in cultured rat mesangial cells. Diabetes. 1992;41:1165–1171. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.41.9.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hohman TC, Carper D, Dasgupta S, Kaneko M. Osmotic stress induces aldose reductase in glomerular endothelial cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1991;284:139–152. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-5901-2_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noh H, King GL. The role of protein kinase C activation in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int Suppl. 2007;106:S49–S53. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kapor-Drezgic J, Zhou X, Babazono T, Dlugosz JA, Hohman T, Whiteside C. Effect of high glucose on mesangial cell protein kinase C-delta and -epsilon is polyol pathway-dependent. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:1193–1203. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1061193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishii H, Tada H, Isogai S. An aldose reductase inhibitor prevents glucose-induced increase in transforming growth factor-beta and protein kinase C activity in cultured mesangial cells. Diabetologia. 1998;41:362–364. doi: 10.1007/s001250050916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oates PJ, Mylari BL. Aldose reductase inhibitors: therapeutic implications for diabetic complications. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 1999;8:2095–2119. doi: 10.1517/13543784.8.12.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung SS, Chung SK. Aldose reductase in diabetic microvascular complications. Curr Drug Targets. 2005;6:475–486. doi: 10.2174/1389450054021891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oates PJ. Aldose reductase inhibitors and diabetic kidney disease. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;11:402–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.So WY, Wang Y, Ng MC, et al. Aldose reductase genotypes and cardiorenal complications: an 8-year prospective analysis of 1,074 type 2 diabetic patients. Diab Care. 2008;31:2148–2153. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heesom AE, Hibberd ML, Millward A, Demaine AG. Polymorphism in the 5′-end of the aldose reductase gene is strongly associated with the development of diabetic nephropathy in type I diabetes. Diabetes. 1997;46:287–291. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.46.2.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moczulski DK, Burak W, Doria A, et al. The role of aldose reductase gene in the susceptibility to diabetic nephropathy in type II (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1999;42:94–97. doi: 10.1007/s001250051119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neamat-Allah M, Feeney SA, Savage DA, et al. Analysis of the association between diabetic nephropathy and polymorphisms in the aldose reductase gene in type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2001;18:906–914. doi: 10.1046/j.0742-3071.2001.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah VO, Scavini M, Nikolic J, et al. Z-2 microsatellite allele is linked to increased expression of the aldose reductase gene in diabetic nephropathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:2886–2891. doi: 10.1210/jc.83.8.2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu M, Chen X, Yan L, Cheng H, Chen W. Association between (AC)n dinucleotide repeat polymorphism at the 5′-end of the aldose reductase gene and diabetic nephropathy: a meta-analysis. J Mol Endocrinol. 2008;40:243–251. doi: 10.1677/JME-07-0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moczulski DK, Scott L, Antonellis A, et al. Aldose reductase gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2000;17:111–118. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maeda S, Haneda M, Yasuda H, et al. Diabetic nephropathy is not associated with the dinucleotide repeat polymorphism upstream of the aldose reductase (ALR2) gene but with erythrocyte aldose reductase content in Japanese subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 1999;48:420–422. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamaoka T, Nishimura C, Yamashita K, et al. Acute onset of diabetic pathological changes in transgenic mice with human aldose reductase cDNA. Diabetologia. 1995;38:255–261. doi: 10.1007/BF00400627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ng DP, Hardy CL, Burns WC, et al. Prevention of diabetes-induced albuminuria in transgenic rats overexpressing human aldose reductase. Endocrinology. 2002;18:47–56. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:18:1:47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beyer-Mears A, Mistry K, Diecke FP, Cruz E. Zopolrestat prevention of proteinuria, albuminuria and cataractogenesis in diabetes mellitus. Pharmacology. 1996;52:292–302. doi: 10.1159/000139394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCaleb ML, McKean ML, Hohman TC, Laver N, Robison WG., Jr Intervention with the aldose reductase inhibitor, tolrestat, in renal and retinal lesions of streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Diabetologia. 1991;34:695–701. doi: 10.1007/BF00401513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tilton RG, Chang K, Pugliese G, et al. Prevention of hemodynamic and vascular albumin filtration changes in diabetic rats by aldose reductase inhibitors. Diabetes. 1989;38:1258–1270. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.38.10.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daniels BS, Hostetter TH. Aldose reductase inhibition and glomerular abnormalities in diabetic rats. Diabetes. 1989;38:981–986. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.38.8.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faiman G, Ganguly P, Mehta A, Thliveris JA. Effect of statil on kidney structure, function and polyol accumulation in diabetes mellitus. Mol Cell Biochem. 1993;125:27–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00926831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McAuliffe AV, Brooks BA, Fisher EJ, Molyneaux LM, Yue DK. Administration of ascorbic acid and an aldose reductase inhibitor (tolrestat) in diabetes: effect on urinary albumin excretion. Nephron. 1998;80:277–284. doi: 10.1159/000045187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pedersen MM, Christiansen JS, Mogensen CE. Reduction of glomerular hyperfiltration in normoalbuminuric IDDM patients by 6 mo of aldose reductase inhibition. Diabetes. 1991;40:527–531. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.40.5.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao D, Fan ST, Chung SS. Identification and characterization of a novel human aldose reductase-like gene. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11429–11435. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.19.11429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallner EI, Wada J, Tramonti G, Lin S, Srivastava SK, Kanwar YS. Relevance of aldo-keto reductase family members to the pathobiology of diabetic nephropathy and renal development. Ren Fail. 2001;23:311–320. doi: 10.1081/JDI-100104715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barski OA, Gabbay KH, Grimshaw CE, Bohren KM. Mechanism of human aldehyde reductase: characterization of the active site pocket. Biochemistry. 1995;34:11264–11275. doi: 10.1021/bi00035a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ho HT, Chung SK, Law JW, et al. Aldose reductase-deficient mice develop nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5840–5846. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.16.5840-5846.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang JY, Tam WY, Tam S, et al. Genetic restoration of aldose reductase to the collecting tubules restores maturation of the urine concentrating mechanism. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291:F186–F195. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00506.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aida K, Ikegishi Y, Chen J, et al. Disruption of aldose reductase gene (Akr1b1) causes defect in urinary concentrating ability and divalent cation homeostasis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;277:281–286. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen MP, Lautenslager GT, Shearman CW. Increased urinary type IV collagen marks the development of glomerular pathology in diabetic d/db mice. Metabolism. 2001;50:1435–1440. doi: 10.1053/meta.2001.28074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steffes MW, Bilous RW, Sutherland DE, Mauer SM. Cell and matrix components of the glomerular mesangium in type I diabetes. Diabetes. 1992;41:679–684. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.41.6.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Forbes JM, Coughlan MT, Cooper ME. Oxidative stress as a major culprit in kidney disease in diabetes. Diabetes. 2008;57:1446–1454. doi: 10.2337/db08-0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kashihara N, Haruna Y, Kondeti VK, Kanwar YS. Oxidative stress in diabetic nephropathy. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:4256–4269. doi: 10.2174/092986710793348581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Obrosova IG. Increased sorbitol pathway activity generates oxidative stress in tissue sites for diabetic complications. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:1543–1552. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Drel VR, Pacher P, Stevens MJ, Obrosova IG. Aldose reductase inhibition counteracts nitrosative stress and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activation in diabetic rat kidney and high-glucose-exposed human mesangial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:1454–1465. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cohen MP. Aldose reductase, glomerular metabolism, and diabetic nephropathy. Metabolism. 1986;35:55–59. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(86)90188-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dan Q, Wong RL, Yin S, Chung SK, Chung SS, Lam KS. Interaction between the polyol pathway and non-enzymatic glycation on mesangial cell gene expression. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2004;98:e89–e99. doi: 10.1159/000080684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Itagaki I, Shimizu K, Kamanaka Y, et al. The effect of an aldose reductase inhibitor (Epalrestat) on diabetic nephropathy in rats. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1994;25:147–154. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(94)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Donnelly SM, Zhou XP, Huang JT, Whiteside CI. Prevention of early glomerulopathy with tolrestat in the streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat. Biochem Cell Biol. 1996;74:355–362. doi: 10.1139/o96-038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keogh RJ, Dunlop ME, Larkins RG. Effect of inhibition of aldose reductase on glucose flux, diacylglycerol formation, protein kinase C, and phospholipase A2 activation. Metabolism. 1997;46:41–47. doi: 10.1016/S0026-0495(97)90165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sharma K, McGowan TA. TGF-beta in diabetic kidney disease: role of novel signaling pathways. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2000;11:115–123. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6101(99)00035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu Y, Usui HK, Sharma K. Regulation of transforming growth factor beta in diabetic nephropathy: implications for treatment. Semin Nephrol. 2007;27:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wong TY, Phillips AO, Witowski J, Topley N. Glucose-mediated induction of TGF-beta 1 and MCP-1 in mesothelial cells in vitro is osmolality and polyol pathway dependent. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1404–1416. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Histomorphology of renal outer medulla/cortex junction areas in six treatment groups of mice at the age of 25 weeks, as determined by PAS staining. PAS staining was performed as described. The results were typical of three mice for each treatment group. Original magnification ×1,000. In contrast to the significant differences in the cortex/glomeruli areas, the outer medullary areas did not shown apparent histomorphological differences among genotype groups of mice or between the non-diabetic and diabetic mice (PDF 1.23 mb)

Histomorphology of renal inner medulla in six treatment groups of mice at the age of 25 weeks as determined by PAS staining. PAS staining was performed as described. The results were typical of three mice for each treatment group. Original magnification, ×1,000. Among the Cit-injected non-diabetic mice, the Ar-KO mice showed more compacted and moderately disorganised medullary structures and PAS-positive staining (dark purple), indicative of medullary atrophy/shrinkage and fibrosis. These defects to a certain degree were improved in the Cit-injected BT mice. In comparison with the non-diabetic mice, severe tubular atrophy (yellow arrows indicated) was observed in the inner medullary areas for all three diabetic mouse groups. The tubulointerstitial lesions in the diabetic BT mice, however, appeared to be slightly improved (less tubular atrophy and less PAS staining) compared with that of the diabetic KO mice. These PAS staining results were further confirmed by the haematoxylin and eosin staining (data not included) (PDF 1.10 mb)

Renal cortical content of reduced GSH and MDA, and renal cortical activity of SOD in six treatment groups of mice at the age of 25 weeks. GSH was measured using a commercial kit from Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. MDA was assayed with a commercial kit from Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, following the manufacturer’s instructions. SOD levels were measured using commercial kits from Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, following the manufacturer’s instructions. a Renal cortical content of GSH in six treatment groups of mice (n = 3); *p < 0.05 (Student’s t test). b Renal cortical content of GSH in six treatment groups of mice (n = 3). c Renal cortical activity of SOD in six treatment groups of mice (n = 3) (PDF 79.8 kb)

(PDF 73.0 kb)