Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory-demyelinating and neurodegenerative disease of the central nervous system (CNS) and the most frequent cause of non-traumatic disability in young and middle-age adults. Although conventional MRI (including T2-weighted, pre- and post-contrast T1-weighted scans) has had a huge impact on MS by enabling an earlier diagnosis, and by providing surrogate markers for monitoring treatment response, it is limited by the low pathological specificity and the low sensitivity to diffuse damage in normal-appearing white matter and gray matter. Diffusion weighted MRI is a quantitative technique able to overcome these limitations by providing markers more specific to the underlying pathologic substrates and more sensitive to the full extent of ‘occult’ brain tissue damage. This review describes diffusion studies in MS, discusses their pathophysiological implications and emphasizes their clinical relevance.

Keywords: diffusion tensor imaging, diffusion tensor tractography, multiple sclerosis, pathological correlates, clinical outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory-demyelinating and neurodegenerative disease of the central nervous system (CNS) and the most common cause of non-traumatic disability in young and middle-age adults (1). MS is estimated to affect more than 400,000 persons in the United States and 2 million people worldwide (2). Although the etiology of the disease is still unknown, several lines of evidence, derived from the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, support the autoimmune pathogenesis of the disease (3). Pathologically, MS is characterized by areas of demyelinated plaques scattered throughout the CNS with a predilection for optic nerves, spinal cord, periventricular white matter (WM), corpus callosum and, as demonstrated by more recent correlative MRI-histological studies, cortical and sub-cortical gray matter (GM) (3). MS lesions reveal a great heterogeneity with respect to the presence and extent of inflammation, demyelination, axonal injury, gliosis and remyelination (4). Similar pathological features have been described, albeit to a lesser extent, in normal-appearing brain tissue (NABT) (5–6).

Approximately 85% of MS patients experience a relapsing-remitting (RR) clinical course characterized by the episodic onset of symptoms followed by residual deficits or by a full recovery especially in the early stage of the disease (7). While within 25 years, most of untreated RRMS patients will evolve into a secondary progressive (SP) phase characterized by a chronic and steady increase of disability, 20% of RRMS patients will remain clinically stable for two decades and will be classified as benign MS (BMS). Finally, 10–15% of MS patients experience a primary progressive (PP) course since the onset in absence of relapses (8).

Although the diagnosis of MS is still based on clinical findings, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is now integrated in the diagnostic criteria of the disease because of its unique sensitivity in demonstrating dissemination in space and time of demyelinating lesions in the brain and spinal cord (9). Conventional MRI (including T2-weighted, pre- and post-contrast T1-weighted scans) has had a huge impact on MS by enabling an earlier diagnosis, and by providing surrogate markers for monitoring response to current disease-modifying treatments and upcoming experimental agents. Despite its increasing role in the clinical management and scientific investigation of MS, conventional MRI is limited by low pathological specificity and low sensitivity to diffuse damage in normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) and gray matter (NAGM). In addition, conventional MRI shows only limited associations with clinical status.

Diffusion weighted MRI is a quantitative technique able to overcome these limitations by providing markers more specific to the underlying pathologic substrates of the disease and more sensitive to the full extent of ‘occult’ tissue damage in patients with MS. Diffusion measures the microscopic Brownian motion of water molecules. This motion is hindered by cellular structures such as cell membranes and axonal cytoskeletons (10). The diffusion tensor is a mathematical description of the magnitude and directionality (anisotropy) of water molecules movement in the three-dimensional space (11). Since in brain white matter, the motion of water molecules can be hindered by the presence of highly organized myelin fiber tracts, water molecules move more easily parallel to tracts and are restricted in their movement perpendicular to tracts. The diffusion tensor can be diagonalized to obtain three eigenvalues or diffusivities (λ1, λ2, and λ3), which can be combined to define several quantitative scalar indices such as mean diffusivity (MD), equal to the magnitude of diffusion, and fractional anisotropy (FA), which represent a measure of fiber integrity and directionality (11). In the CNS, λ1 represents the water diffusivity parallel to the axonal fibers and is referred to as λ||, axial diffusivity. The water diffusivity perpendicular to the axonal fibers, λ2, and λ3 are averaged and referred to as λ ⊥ = (λ2 + λ3)/2, radial diffusivity (12). Abnormalities in diffusivity patterns have been seen both in focal MS lesions and in NAWM and NAGM. In this review we summarize the studies that have investigated the diffusion characteristics of tissue damage in patients with MS with the ultimate aim of providing insights into the disease pathophysiology and discussing the clinical implications.

PATHOLOGICAL CORRELATES OF DIFFUSION MRI METRICS IN MS

Histopathologically, MS is characterized by demyelination, axonal injury, inflammation, gliosis and remyelination (4). A few studies have investigated the pathological correlates of diffusion imaging in MS (13–14). In a post-mortem study of patients with progressive MS and chronic lesions Schmierer and colleagues (15) found a strong correlation of MD and FA with myelin content and—to a lesser degree—axonal count and fibrillary gliosis suggesting that, in chronic post-mortem MS brain, MD and FA are mainly affected by demyelination. Compared to values acquired during in vivo study of MS patients, post-mortem studies exhibit reduction in average MD and FA both in lesions and in NAWM. This reduction in diffusivity of brain tissue following death is a well-recognized phenomenon and it is likely due to several factors, including dehydration of post-mortem tissue, the lower temperature during post mortem MRI and the breakdown of energy-dependent ion transport mechanisms resulting in a net influx of water into cells and reduction of the extra-cellular space (16–17).

DIFFUSION MRI AND LESION EVOLUTION

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) has proved to be a valuable tool for investigating the variety of pathological features of T2-visible lesions. Increased MD and decreased FA are always more pronounced in lesions than in the NAWM; however their values are highly heterogeneous indicating the variable degrees of tissue damage occurring within MS lesions (18–21). As expected, the more severe MD abnormalities have been found in non-enhancing T1 hypointense lesions which represent areas of irreversible tissue disruption, gliosis, and axonal loss (22) and consequent loss of structural barriers to water diffusion (Fig. 1). Conversely, conflicting results have been obtained when comparing Gd-enhancing lesions vs non-enhancing lesions: one study demonstrated that Gd-enhancing lesions have higher MD values (20) but others did not find any significant difference between the two groups of lesions (21,23–24). This discrepancy might be due to methodological issues or might reflect the concurrent presence of destructive and reparative processes. Along this line, a longitudinal study of Gd-enhancing lesions which were followed up for 1 to 3 months showed that MD values were increased in all lesions at baseline, but continued to increase only in a sub-group of them at follow-up. Furthermore, increased MD values were correlated with a greater degree of T1-hypointensity (25). This suggests that some of the tissue abnormalities in acute lesions are related to neurodegeneration and, therefore, are permanent whereas some other tissue abnormalities are related to edema, demyelination and remyelination. Unlike MD, FA is always lower in Gd-enhancing lesions, especially the ring-enhancing ones (23), than in the non-enhancing lesions reflecting demyelination, axonal injury and accumulation of inflammatory cells (20–21,26). Interestingly, a recent study (27) has reported increased MD and FA values in cortical lesions of MS patients relative to the cortical GM of healthy controls. The increased anisotropy in cortical lesions is opposite to the decrease of FA found in WM lesions and suggests that the reduced dendritic arborization, typical of cortical lesions, might increase coherence, and consequently, diffusion anisotropy.

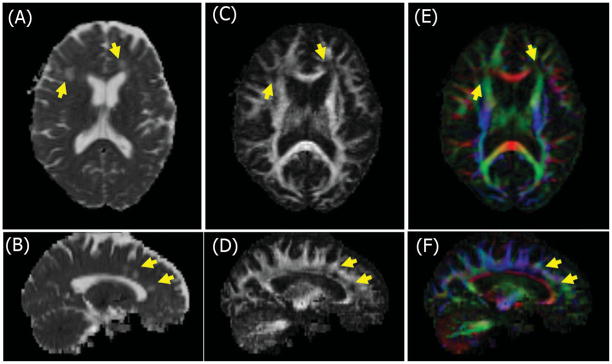

Figure 1.

Selected axial and sagittal diffusion tensor maps from a patient with multiple sclerosis. Mean diffusivity (A, B), fractional anisotropy (C, D) and color primary eigenvector map (E, F) illustrating different directions of the primary eigenvector: Red is left-right; green is cranio-caudal and blue is in-out of the page. Note that MS lesions (arrows) show higher mean diffusivity (bright), lower fractional anisotropy (dark) and disruption of the primary fiber direction (dark).

DIFFUSION MRI AND ‘OCCULT’ INJURY IN NAWM AND NAGM

Although conventional MRI is very sensitive to macroscopic lesions, it lacks sensitivity to the ‘occult’ microscopic pathology involving NAWM and NAGM (5–6). In contrast, several studies have described abnormalities of diffusion MRI metrics outside T2 lesions in NAWM and in NAGM of MS patients (21,28–32) contributing to improve our understanding of MS pathophysiology. Werring and colleagues demonstrated that a steady and moderate increase of apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) can precede the development of new plaques (33) and be followed by a rapid and marked increase at the time of Gadolinium enhancement and a slower decay after the cessation of enhancement. Thus, suggesting that new lesions are preceded by progressive, albeit subtle, tissue abnormalities beyond the resolution of conventional MRI. Interestingly, a milder increase of ADC was also detected in regions of NAWM contralateral to the newly appeared lesions supporting the concept that NAWM abnormalities are due the secondary degeneration of axons transected within lesions. However, MD and FA of NAWM and NAGM are only partially correlated with the extent of focal lesions and the severity of intrinsic lesion damage suggesting that diffusivity changes in normal-appearing tissue are not the mere consequence of retrograde degeneration of axons transected in T2-visible lesions. Indeed, astrocytic hyperplasia, patchy edema, perivascular infiltration, demyelination and axonal loss may also contribute to the diffusion abnormalities of normal-appearing brain tissue (5–6). Moreover, several DTI studies have shown that NAWM injury become more pronounced with increasing disease duration and clinical disability (34–36) suggesting that DTI is likely to be sensitive to more severe pathological processes. Since MS is a diffuse and widespread disease of the CNS, the analysis of DTI changes can be performed on a global basis using histogram analysis (Cercignani, 2000, pathologic; Nusbaum, 2000, histograms; Iannucci, 2001, correlation}. MS patients have significantly higher average MD, lower histogram peak height MD and lower average FA than healthy controls. These DTI changes are significantly more severe in patients with SPMS than in those with RR-MS (37–39) supporting a role for DTI in monitoring advanced stages of the disease (21). Several DTI studies (20–21,34,40–41) have also investigated patients with primary-progressive (PP) MS, in the attempt to clarify the pathophisiology of this MS subgroup characterized by atypical MRI features: few lesions and little Gadolinium enhancement (42). Although MD and FA abnormalities were described in NAWM and NAGM of these patients, no significant correlation was found between lesion load and DTI abnormalities in normal-appearing tissue suggesting that microscopic diffuse brain changes in these patients are independent from T2-visible lesions (34,41). Histogram-derived DTI metrics could be particularly useful for monitoring disease progression and treatment response because they enable the assessment of the global disease burden including macroscopic lesions and microscopic injury in NAWM and NAGM. In other studies, however, the assessment of regional damage using DTI proved to be more sensitive than a global approach to gain insight on the imaging correlates of the clinical status in MS. Using a voxel-based approach, a recent study (43) showed that patients with RR and benign MS differ in topographic distribution of WM damage rather than in the global extent of brain structural changes. Specifically, the less prominent involvement of the frontal lobe WM in benign MS might be associated to the favorable clinical status. Changes of DTI metrics have been described in cortical and subcortical NAGM (30,34,40,44–47). RRMS patients exhibit average NAGM MD higher than that of age and sex matched healthy controls and NAGM MD is higher in patients with SPMS and PPMS than in those with RRMS (30,34,40). NAGM abnormalities might be due to the presence of cortical lesions which are often undetected on T2-weighted images and/or to the retrograde degeneration of cortical neurons secondary to the injury of axons in WM lesions (48–49).

DIFFUSION MRI OF SPINAL CORD AND OPTIC NERVES

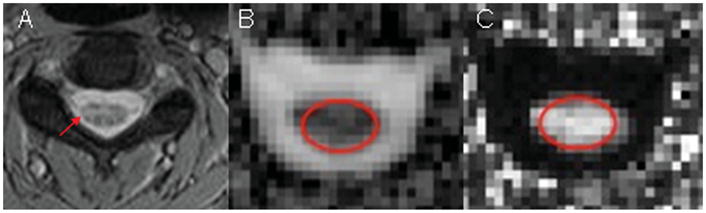

The spinal cord and the optic nerves are common sites of pathology in multiple sclerosis; however, diffusion MRI in these regions presents a considerable technical challenge (50). The majority of cord lesions are limited to one to two spinal cord segments and involve less than half of the cross-sectional area of the cord (51). Similar to the brain, conventional MRI is unable to grade the extent of tissue injury within macroscopic lesions, as well as to detect and quantify the ‘occult’ damage known to occur in the normal-appearing cord of patients with MS (52). Since spinal cord damage is likely to contribute to the accumulation of disability, there is a need to assess spinal cord involvement in MS with new imaging techniques in order to understand better the underlying pathology. Changes in patients with MS have recently been detected in the cervical spinal cord using sagittal DTI and evaluating large regions of interest with the use of histogram analysis (23,53–56) (Valsasina, 2005, histogram; Agosta, 2005, primary; Benedetti, 2009, benign}. Since lesions in primary demyelination have a predilection for the posterior columns of the spinal cord, an analysis of DTI metrics in regions of the spinal cord may be useful to demonstrate spatial differences (57) (Fig. 2). Patients with RRMS, SPMS and PPMS have MD and FA histogram characteristics suggestive of diffuse cord injury (58); moreover, it has been shown that, in these patients, cord FA and brain average MD are independent variables of clinical disability. When patients with benign MS are compared with patients with SPMS, they present milder cord injury with cord FA and cross-sectional area being independent factors associated with the degree of clinical disability (56). Finally, Ciccarelli and colleagues (59), have demonstrated that the combination of MR spectroscopy and diffusion MRI of the cervical cord not only provide measures that are sensitive to the tissue damage occurring in this area but enable a more comprehensive assessment of spinal cord and clinical disability.

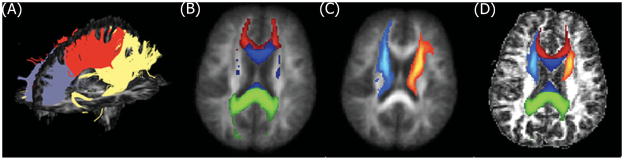

Figure 2.

Selected axial T2-weighted image (A) of the cervical spinal cord of a MS patient acquired at C3 level (the arrow indicates a hyperintense lesion). MD (B) and FA (C) maps corresponding to the level of the T2 weighted image.

The optic nerves (ONs) provide an ideal structure for study by diffusion MRI (60–63); increases in MD and reductions in FA of ONs have been shown to provide a marker of the structural integrity of axons. Using zonal oblique multislice echoplanar imaging (64) in patients with a single episode of unilateral optic neuritis, Trip and colleagues (62) demonstrated that MD and FA measures of the affected ONs were impaired and increased MD and decreased FA were correlated with the amplitude of the visual evoked potential. Kolbe and colleagues showed that decreased FA and volume of the ON are independent predictors of visual dysfunction 4 years after an episode of unilateral optic neuritis (65). A recent study employed diffusion tensor imaging of the ON and optical coherence tomography to study patients with acute, isolated optic neuritis (66). The decrease in axial diffusivity at onset correlated with visual contrast sensitivity 1 and 3 months later. Since changes in axial diffusivity are thought to reflect axonal injury, the decline of axial diffusivity in the acute setting has potential as a surrogate marker of tissue destruction and outcome. This is further supported by the data collected from three patients who were imaged serially from the acute episode. Axial diffusivity correlated with the thickness of the retinal fiber layer measured by optical coherence tomography, and visual acuity suggesting the potential of axial diffusivity as a predictor of future clinical outcome.

LONGITUDINAL DIFFUSION MRI STUDIES

Few studies have investigated the utility of diffusion imaging in monitoring the temporal evolution of MS damage both in lesions and NABT over time (35,67–70). A longitudinal study of patients in the earliest stage of MS suggested a progressive increase of NAWM diffusivity over 1 year (67). An increase in NAWM diffusivity was also observed in patients with PPMS over the course of 1 year (70). In a study of untreated RRMS patients, a significant decrease of average NAGM FA and increase of average NAGM MD was observed over 18-month follow-up (69). In a large cohort of patients with PPMS, a significant decrease of average NAGM was detected after one-year follow-up (35). Agosta and colleagues (71) used conventional and DT MRI to investigate the temporal evolution of intrinsic tissue injury and atrophy in the cervical cord and their relationship with brain damage and disability. Both cord cross-sectional area and FA decreased during follow-up but they were not strictly correlated suggesting that a multiparametric MRI approach is needed to achieve more accurate estimates of such damage. MS cord pathology was also found to be independent of concurrent brain changes, to develop at a different rate in different MS subgroups and to be associated with medium-term disability accrual. However, the precision and accuracy of DTI in detecting longitudinal, MS-related changes need to be defined and large, prospective studies are warranted. This issue is central for future application of DTI to the monitoring of the disease evolution in MS clinical trials and, eventually, in the assessment of individual patients.

DIFFUSION TENSOR IMAGING TRACTOGRAPHY

Diffusion-based tractography is a technique based on the directional movement of water which allows the generation of a non invasive three dimensional representation of white matter fiber tracts (72). The application of DTI tractography in MS is limited by the presence of both focal and diffuse alteration of tissue organization, which results in a decreased anisotropy and a consequent increase in uncertainty of the primary eigenvector of the DT (73). As a consequence, the low FA can erroneously terminate the tracking algorithm or cause a deviation of the bundles at the level of the lesions (72). A possible approach to overcome this problem is the use of probability maps of tract of interest obtained from healthy subjects to assess DTI metrics from the corresponding patients’ tracts (74–75) (Fig. 3). Using this method, A DTI tractography study of patients in the earliest stage of MS showed that those patients who had motor impairment had increased MD and T2 lesion volume in the cortico-spinal tract (CST) compared with those patients who did not have pyramidal symptoms (74). A DTI tractography study of patients who had optic neuritis showed reduced connectivity values both in left and right optic radiations compared with controls, suggesting the occurrence of transynaptic degeneration secondary to optic nerve damage (76). DTI tractography also provided a method to identify NAWM fibers at risk of degeneration when intersecting T2 visible lesions (77). In patients with MS, MD and FA of the CST correlate with clinical measures of locomotor disability, such as the expanded disability status scale (EDSS) score or the pyramidal functional system score at this scale, more than T2 lesion burden and the overall extent of diffusivity changes of the brain (78). The analysis of radial and axial diffusivity of the CST of patients who have RRMS has suggested Wallerian degeneration as the main mechanism underlying diffusion changes in this WM structure. More recently, tract-specific abnormalities of the CST were investigated using a multiparametric approach, which included DTI tractography, magnetization transfer imaging (MTI) and T2 relaxation times in a large cohort of patients with MS (79). On average, tract profiles were different between patients and controls, particularly in subcortical WM and corona radiata for all indices examined except for FA suggesting that a multiparametric approach may provide a better description of the pathological substrates of the disease. A study (80) combining measures of tractography and measures of functional connectivity showed that these measures are correlated in MS patients thus suggesting that injury of WM fibers may induce functional adaptive changes that limit its clinical manifestations (80). Although DTI tractography has the potential to improve our understanding of damage in brain and spinal cord, the interpretation of data requires caution and a priori knowledge.

Figure 3.

3D DTI-tractography of the corpus callosum (CC) (A) in a healthy control. CC (B) and antero-thalamic (AT) (C) tract probability maps in MNI space and in the corresponding single subject space (D) after transformation.

CLINICAL RELEVANCE OF DIFFUSION MRI STUDIES

Recent studies have reported significant correlation between DTI findings and MS clinical symptoms and disability and suggested a role for DTI as predictive indicator of clinical outcome and as a tool for monitoring response to treatment in clinical trials. The strongest association with clinical disability has been reported with the diffusion characteristics of T2 lesions and GM (81–84). While a study was not able to find correlations between DTI metrics and the presence and severity of fatigue in MS patients(85), other studies have suggested some role for DTI-derived measures in explaining the correlates of cognitive impairment (81,84).

Approximately 50% of MS patients exhibit some degree of neuropsychological (NP) impairment (86). Identifying patients at risk for NP impairment on the basis of MRI would thus enhance quality of care. It is increasingly recognized that early pathological changes in the normal-appearing brain tissue may predict cognitive disorders in MS. Diffusion-derived measures may account for clinical signs independent of variance explained by more conventional, macroscopic MRI measures. Rovaris and colleagues (81) examined the relationship between DTI metrics and cognition in RRMS patients with mild neurological disability. Modest but significant correlations were found between mean brain diffusivity and cognitive tests measuring memory, speed of information processing and verbal fluency. Benedict and colleagues (84) investigated a larger sample of both patient with RRMS and SPMS grouped as either cognitively impaired or intact, and found that cognitive impairment was associated with more brain injury as measured by ADC, lesion volume and atrophy. The results of a follow-up study in patients with PPMS suggest that the severity of NAGM MD may predict the accumulation of clinical disability 5 years later (87). Few ongoing studies are investigating the utility of DTI in monitoring treatment efficacy (88–89).

The promising results of diffusion imaging studies in MS and other neurological diseases have prompted several interesting technical developments aimed at improving the sensitivity and pathological specificity of the technique. Over the last few years, more complex diffusion models or model-free methods have been suggested which can better describe architectures more complex than a single coherently oriented fiber bundle (i.e. fiber crossing). Technical improvements are aimed both at a better segmentation of fiber bundles and at a better understanding of tissue structure-function relationship (for instance, characterizing distinct anatomical compartments within a voxel). For the first-type technical improvement, important contributes have been provided by methods such as HARDI (90), the deconvolution approach (91) and the Q-ball approach (92). For the second-type technical improvement, q-space and kurtosis imaging have provided promising findings in research applications. High b-value q-space imaging, which emphasizes the diffusion characteristics of the slow-diffusing component, has shown higher sensitivity to the pathophysiological changes in lesions and NAWM of MS patients when compared to DTI (93). In addition, q-space diffusion metrics correlated well with N-acetylaspartate levels suggesting their possible higher specificity for axonal injury (94). Diffusional kurtosis imaging (95) which is related to q-space imaging methods, but is less demanding in terms of imaging time, hardware requirements, and post-processing effort may prove particularly useful in several neurological disorders, including MS (Fig. 4). This method provides a specific measure of tissue structure, such as cellular compartments and membranes and has been shown to be able to characterize and measure age-related diffusion changes not only for white matter but also for gray matter (96).

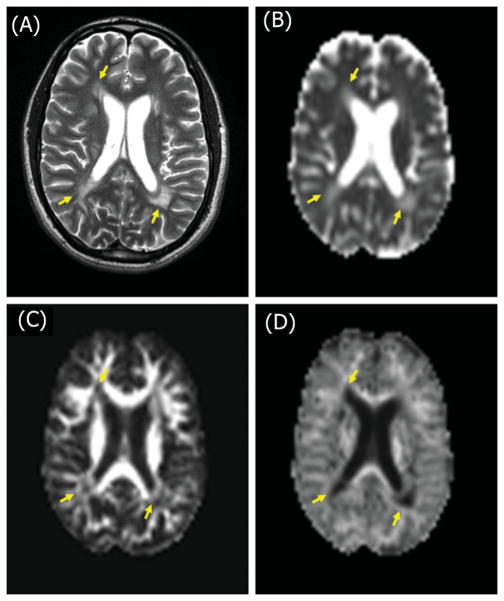

Figure 4.

Selected T2-weighted image of a MS patient (A) showing multiple periventricular hyperintense lesions (arrows). Corresponding MD (B), FA (C) and MK (D) maps.

CONCLUSIONS

The current application of diffusion MRI to patients with MS shows that it has enhanced our understanding of the disease pathophisiology. The studies reviewed here provide evidence that DTI-derived measures are more specific to the disease pathological processes and sensitive to the diffuse microscopic injury in the NAWM and NAGM. From a clinical point of view, DTI-derived measures correlate with physical disability and cognitive impairment and the degree of DTI changes in normal-appearing tissue may have predictive value of the subsequent clinical evolution. Furthermore, DTI-derived measures hold promise as a tool for monitoring treatment response in MS clinical trials. However, the precision and accuracy of DTI in detecting MS-related tissue changes also need to be confirmed in large, prospective studies. Future developments in acquisition and post-processing strategies and clinical application at higher field strength should lead to higher spatial resolution, higher precision of diffusion imaging measures and improve their pathological specificity.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the US National Institute of Health (grant number R01 NS051623 and R01 NS029029).

Contract/grant sponsor: US National Institute of Health; contract/grant numbers: R01 NS051623; R01 NS029029.

Abbreviations used

- ADC

Apparent diffusion coefficient

- BMS

benign multiple sclerosis

- CNS

central nervous system

- CST

cortico-spinal Tract

- DTI

diffusion tensor imaging

- EDSS

expanded disability status scale

- FA

fractional anisotropy

- GM

gray matter

- HARDI

high-angular resolution diffusion imaging

- MD

mean diffusivity

- MK

mean kurtosis

- MNI

Montréal Neurological Institute

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- MTI

magnetization transfer imaging

- NABT

normal-appearing brain tissue

- NAGM

normal-appearing gray matter

- NAWM

normal-appearing white matter

- NP

neuropsychological

- ON

optic nerve

- OCT

optical coherence tomography

- PPMS

primary progressive

- RRMS

relapsing remitting

- SPMS

secondary progressive

- WM

white matter

Footnotes

This article is published in NMR in Biomedicine as a special issue on Progress in Diffusion-Weighted Imaging: Concepts, Techniques, and Applications to the Central Nervous System, edited by Jens H. Jensen and Joseph A. Helpern, Center for Biomedical Imaging, Department of Radiology, NYU School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA.

References

- 1.Rodriguez M, Siva A, Ward J, Stolp-Smith K, O’Brien P, Kurland L. Impairment, disability, and handicap in multiple sclerosis: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Neurology. 1994;44(1):28–33. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hauser SL. Multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating diseases. In: Isselbacher KJWJ, Martin JB, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, editors. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1994. pp. 2287–2295. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lassmann H. Pathology of Multiple Sclerosis. In: Compston A, Ebers G, Lassmann H, McDonald WI, Matthews B, Wekerle H, editors. McAlpine’s Multiple Sclerosis. Churchill Livingstone; London: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lassmann H, Bruck W, Lucchinetti C. Heterogeneity of multiple sclerosis pathogenesis: implications for diagnosis and therapy. Trends Mol Med. 2001;7(3):115–121. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(00)01909-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen IV, McKeown SR. A histological, histochemical and biochemical study of the macroscopically normal white matter in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 1979;41(1):81–91. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(79)90142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterson JW, Bo L, Mork S, Chang A, Trapp BD. Transected neurites, apoptotic neurons, and reduced inflammation in cortical multiple sclerosis lesions. Ann Neurol. 2001;50(3):389–400. doi: 10.1002/ana.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinshenker BG, Bass B, Rice GP, Noseworthy J, Carriere W, Baskerville J, Ebers GC. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study. I. Clinical course and disability. Brain. 1989;112(Pt 1):133–146. doi: 10.1093/brain/112.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lublin FD, Reingold SC. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: results of an international survey. National Multiple Sclerosis Society (USA) Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials of New Agents in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology. 1996;46(4):907–911. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.4.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonald WI, Compston A, Edan G, Goodkin D, Hartung HP, Lublin FD, McFarland HF, Paty DW, Polman CH, Reingold SC, Sandberg-Wollheim M, Sibley W, Thompson A, van den Noort S, Weinshenker BY, Wolinsky JS. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the International Panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2001;50(1):121–127. doi: 10.1002/ana.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le Bihan D, Mangin JF, Poupon C, Clark CA, Pappata S, Molko N, Chabriat H. Diffusion tensor imaging: concepts and applications. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;13(4):534–546. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basser PJ. Inferring microstructural features and the physiological state of tissues from diffusion-weighted images. NMR Biomed. 1995;8(7–8):333–344. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940080707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pierpaoli C, Barnett A, Pajevic S, Chen R, Penix LR, Virta A, Basser P. Water diffusion changes in Wallerian degeneration and their dependence on white matter architecture. Neuroimage. 2001;13(6 Pt 1):1174–1185. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mottershead JP, Schmierer K, Clemence M, Thornton JS, Scaravilli F, Barker GJ, Tofts PS, Newcombe J, Cuzner ML, Ordidge RJ, McDonald WI, Miller DH. High field MRI correlates of myelin content and axonal density in multiple sclerosis—a post-mortem study of the spinal cord. J Neurol. 2003;250(11):1293–1301. doi: 10.1007/s00415-003-0192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wheeler-Kingshott CAM, Schmierer K, Ciccarelli O, Boulby P, Parker GJM, Miller DH. Diffusion tensor imaging of post-mortem brain (fresh and fixed) on a clinical scanner. Proc Int Soc Mag Reson Med. 2003;3:422. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmierer K, Wheeler-Kingshott CA, Boulby PA, Scaravilli F, Altmann DR, Barker GJ, Tofts PS, Miller DH. Diffusion tensor imaging of post mortem multiple sclerosis brain. Neuroimage. 2007;35(2):467–477. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.12.010. Epub 2006 Dec 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee VM, Burdett NG, Carpenter TA, Herrod NJ, James MF, Hall LD. Magnetic resonance imaging of the common marmoset head. ATLA. 1998;26:343–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gass A, Niendorf T, Hirsch JG. Acute and chronic changes of the apparent diffusion coefficient in neurological disorders—biophysical mechanisms and possible underlying histopathology. J Neurol Sci. 2001;186 (Suppl 1):S15–23. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(01)00487-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christiansen P, Gideon P, Thomsen C, Stubgaard M, Henriksen O, Larsson HB. Increased water self-diffusion in chronic plaques and in apparently normal white matter in patients with multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 1993;87(3):195–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1993.tb04100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horsfield MA, Lai M, Webb SL, Barker GJ, Tofts PS, Turner R, Rudge P, Miller DH. Apparent diffusion coefficients in benign and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis by nuclear magnetic resonance. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36(3):393–400. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Droogan AG, Clark CA, Werring DJ, Barker GJ, McDonald WI, Miller DH. Comparison of multiple sclerosis clinical subgroups using navigated spin echo diffusion-weighted imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;17(5):653–661. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(99)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Filippi M, Cercignani M, Inglese M, Horsfield MA, Comi G. Diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2001;56(3):304–311. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.3.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Walderveen MA, Kamphorst W, Scheltens P, van Waesberghe JH, Ravid R, Valk J, Polman CH, Barkhof F. Histopathologic correlate of hypointense lesions on T1-weighted spin-echo MRI in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1998;50(5):1282–1288. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.5.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bammer R, Augustin M, Strasser-Fuchs S, Seifert T, Kapeller P, Stollberger R, Ebner F, Hartung HP, Fazekas F. Magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging for characterizing diffuse and focal white matter abnormalities in multiple sclerosis. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44(4):583–591. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200010)44:4<583::aid-mrm12>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Filippi M, Iannucci G, Cercignani M, Assunta Rocca M, Pratesi A, Comi G. A quantitative study of water diffusion in multiple sclerosis lesions and normal-appearing white matter using echo-planar imaging. Arch Neurol. 2000;57(7):1017–1021. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.7.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castriota-Scanderbeg A, Sabatini U, Fasano F, Floris R, Fraracci L, Mario MD, Nocentini U, Caltagirone C. Diffusion of water in large demyelinating lesions: a follow-up study. Neuroradiology. 2002;44(9):764–767. doi: 10.1007/s00234-002-0806-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castriota-Scanderbeg A, Fasano F, Hagberg G, Nocentini U, Filippi M, Caltagirone C. Coefficient D(av) is more sensitive than fractional anisotropy in monitoring progression of irreversible tissue damage in focal nonactive multiple sclerosis lesions. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24(4):663–670. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poonawalla AH, Hasan KM, Gupta RK, Ahn CW, Nelson F, Wolinsky JS, Narayana PA. Diffusion-tensor MR imaging of cortical lesions in multiple sclerosis: initial findings. Radiology. 2008;246(3):880–886. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2463070486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rocca MA, Cercignani M, Iannucci G, Comi G, Filippi M. Weekly diffusion-weighted imaging of normal-appearing white matter in MS. Neurology. 2000;55(6):882–884. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.6.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nusbaum AO, Lu D, Tang CY, Atlas SW. Quantitative diffusion measurements in focal multiple sclerosis lesions: correlations with appearance on TI-weighted MR images. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175(3):821–825. doi: 10.2214/ajr.175.3.1750821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cercignani M, Bozzali M, Iannucci G, Comi G, Filippi M. Magnetisation transfer ratio and mean diffusivity of normal appearing white and grey matter from patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70(3):311–317. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.3.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo AC, MacFall JR, Provenzale JM. Multiple sclerosis: diffusion tensor MR imaging for evaluation of normal-appearing white matter. Radiology. 2002;222(3):729–736. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2223010311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ge Y, Law M, Johnson G, Herbert J, Babb JS, Mannon LJ, Grossman RI. Preferential occult injury of corpus callosum in multiple sclerosis measured by diffusion tensor imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;20(1):1–7. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Werring DJ, Brassat D, Droogan AG, Clark CA, Symms MR, Barker GJ, MacManus DG, Thompson AJ, Miller DH. The pathogenesis of lesions and normal-appearing white matter changes in multiple sclerosis: a serial diffusion MRI study. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 8):1667–1676. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.8.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rovaris M, Bozzali M, Iannucci G, Ghezzi A, Caputo D, Montanari E, Bertolotto A, Bergamaschi R, Capra R, Mancardi GL, Martinelli V, Comi G, Filippi M. Assessment of normal-appearing white and gray matter in patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis: a diffusion-tensor magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(9):1406–1412. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.9.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rovaris M, Gallo A, Valsasina P, Benedetti B, Caputo D, Ghezzi A, Montanari E, Sormani MP, Bertolotto A, Mancardi G, Bergamaschi R, Martinelli V, Comi G, Filippi M. Short-term accrual of gray matter pathology in patients with progressive multiple sclerosis: an in vivo study using diffusion tensor MRI. Neuroimage. 2005;24(4):1139–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pulizzi A, Rovaris M, Judica E, Sormani MP, Martinelli V, Comi G, Filippi M. Determinants of disability in multiple sclerosis at various disease stages: a multiparametric magnetic resonance study. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(8):1163–1168. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.8.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cercignani M, Iannucci G, Rocca MA, Comi G, Horsfield MA, Filippi M. Pathologic damage in MS assessed by diffusion-weighted and magnetization transfer MRI. Neurology. 2000;54(5):1139–1144. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.5.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nusbaum AO, Tang CY, Wei T, Buchsbaum MS, Atlas SW. Whole-brain diffusion MR histograms differ between MS subtypes. Neurology. 2000;54(7):1421–1427. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.7.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iannucci G, Rovaris M, Giacomotti L, Comi G, Filippi M. Correlation of multiple sclerosis measures derived from T2-weighted, T1-weighted, magnetization transfer, and diffusion tensor MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22(8):1462–1467. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bozzali M, Cercignani M, Sormani MP, Comi G, Filippi M. Quantification of brain gray matter damage in different MS phenotypes by use of diffusion tensor MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23(6):985–988. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rocca MA, Iannucci G, Rovaris M, Comi G, Filippi M. Occult tissue damage in patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis is independent of T2-visible lesions—a diffusion tensor MR study. J Neurol. 2003;250(4):456–460. doi: 10.1007/s00415-003-1024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thompson AJ, Kermode AG, Wicks D, MacManus DG, Kendall BE, Kingsley DP, McDonald WI. Major differences in the dynamics of primary and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1991;29(1):53–62. doi: 10.1002/ana.410290111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ceccarelli A, Rocca MA, Pagani E, Ghezzi A, Capra R, Falini A, Scotti G, Comi G, Filippi M. The topographical distribution of tissue injury in benign MS: a 3T multiparametric MRI study. Neuroimage. 2008;39(4):1499–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Filippi M, Bozzali M, Comi G. Magnetization transfer and diffusion tensor MR imaging of basal ganglia from patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2001;183(1):69–72. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(00)00471-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ciccarelli O, Werring DJ, Wheeler-Kingshott CA, Barker GJ, Parker GJ, Thompson AJ, Miller DH. Investigation of MS normal-appearing brain using diffusion tensor MRI with clinical correlations. Neurology. 2001;56(7):926–933. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.7.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fabiano AJ, Sharma J, Weinstock-Guttman B, Munschauer FE, 3rd, Benedict RH, Zivadinov R, Bakshi R. Thalamic involvement in multiple sclerosis: a diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neuroimaging. 2003;13(4):307–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hasan KM, Halphen C, Kamali A, Nelson FM, Wolinsky JS, Narayana PA. Caudate nuclei volume, diffusion tensor metrics, and T(2) relaxation in healthy adults and relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients: implications for understanding gray matter degeneration. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;29(1):70–77. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kidd D, Barkhof F, McConnell R, Algra PR, Allen IV, Revesz T. Cortical lesions in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 1999;122(Pt 1):17–26. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Evangelou N, Konz D, Esiri MM, Smith S, Palace J, Matthews PM. Regional axonal loss in the corpus callosum correlates with cerebral white matter lesion volume and distribution in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 9):1845–1849. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.9.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rovaris M, Gass A, Bammer R, Hickman SJ, Ciccarelli O, Miller DH, Filippi M. Diffusion MRI in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2005;65(10):1526–1532. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000184471.83948.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bot JC, Barkhof F. Spinal-cord MRI in multiple sclerosis: conventional and nonconventional MR techniques. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2009;19(1):81–99. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bergers E, Bot JC, van der Valk P, Castelijns JA, Lycklama a Nijeholt GJ, Kamphorst W, Polman CH, Blezer EL, Nicolay K, Ravid R, Barkhof F. Diffuse signal abnormalities in the spinal cord in multiple sclerosis: direct postmortem in situ magnetic resonance imaging correlated with in vitro high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging and histopathology. Ann Neurol. 2002;51(5):652–656. doi: 10.1002/ana.10170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clark CA, Werring DJ, Miller DH. Diffusion imaging of the spinal cord in vivo: estimation of the principal diffusivities and application to multiple sclerosis. Magn Reson Med. 2000;43(1):133–138. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(200001)43:1<133::aid-mrm16>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cercignani M, Horsfield MA, Agosta F, Filippi M. Sensitivity-encoded diffusion tensor MR imaging of the cervical cord. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24(6):1254–1256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Agosta F, Benedetti B, Rocca MA, Valsasina P, Rovaris M, Comi G, Filippi M. Quantification of cervical cord pathology in primary progressive MS using diffusion tensor MRI. Neurology. 2005;64(4):631–635. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000151852.15294.CB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Benedetti B, Rocca MA, Rovaris M, Caputo D, Zaffaroni M, Capra R, Bertolotto A, Martinelli V, Comi G, Filippi M. A diffusion tensor MRI study of cervical cord damage in benign and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:26–30. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.173120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hesseltine SM, Law M, Babb J, Rad M, Lopez S, Ge Y, Johnson G, Grossman RI. Diffusion tensor imaging in multiple sclerosis: assessment of regional differences in the axial plane within normal-appearing cervical spinal cord. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27(6):1189–1193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valsasina P, Rocca MA, Agosta F, Benedetti B, Horsfield MA, Gallo A, Rovaris M, Comi G, Filippi M. Mean diffusivity and fractional anisotropy histogram analysis of the cervical cord in MS patients. Neuroimage. 2005;26(3):822–828. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.033. Epub 2005 Mar 2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ciccarelli O, Wheeler-Kingshott CA, McLean MA, Cercignani M, Wimpey K, Miller DH, Thompson AJ. Spinal cord spectroscopy and diffusion-based tractography to assess acute disability in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 8):2220–2231. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Iwasawa T, Matoba H, Ogi A, Kurihara H, Saito K, Yoshida T, Matsubara S, Nozaki A. Diffusion-weighted imaging of the human optic nerve: a new approach to evaluate optic neuritis in multiple sclerosis. Magn Reson Med. 1997;38(3):484–491. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910380317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hickman SJ, Wheeler-Kingshott CA, Jones SJ, Miszkiel KA, Barker GJ, Plant GT, Miller DH. Optic nerve diffusion measurement from diffusion-weighted imaging in optic neuritis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26(4):951–956. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Trip SA, Wheeler-Kingshott C, Jones SJ, Li WY, Barker GJ, Thompson AJ, Plant GT, Miller DH. Optic nerve diffusion tensor imaging in optic neuritis. Neuroimage. 2006;30(2):498–505. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kolappan M, Henderson AP, Jenkins TM, Wheeler-Kingshott CA, Plant GT, Thompson AJ, Miller DH. Assessing structure and function of the afferent visual pathway in multiple sclerosis and associated optic neuritis. J Neurol. 2009;256(3):305–319. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-0123-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wheeler-Kingshott CA, Trip SA, Symms MR, Parker GJ, Barker GJ, Miller DH. In vivo diffusion tensor imaging of the human optic nerve: pilot study in normal controls. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56(2):446–451. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kolbe S, Chapman C, Nguyen T, Bajraszewski C, Johnston L, Kean M, Mitchell P, Paine M, Butzkueven H, Kilpatrick T, Egan G. Optic nerve diffusion changes and atrophy jointly predict visual dysfunction after optic neuritis. Neuroimage. 2009;45(3):679–686. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Naismith RT, Xu J, Tutlam NT, Snyder A, Benzinger T, Shimony J, Shepherd J, Trinkaus K, Cross AH, Song SK. Disability in optic neuritis correlates with diffusion tensor-derived directional diffusivities. Neurology. 2009;72(7):589–594. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000335766.22758.cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Caramia F, Pantano P, Di Legge S, Piattella MC, Lenzi D, Paolillo A, Nucciarelli W, Lenzi GL, Bozzao L, Pozzilli C. A longitudinal study of MR diffusion changes in normal appearing white matter of patients with early multiple sclerosis. Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;20(5):383–388. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(02)00519-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cassol E, Ranjeva JP, Ibarrola D, Mekies C, Manelfe C, Clanet M, Berry I. Diffusion tensor imaging in multiple sclerosis: a tool for monitoring changes in normal-appearing white matter. Mult Scler. 2004;10(2):188–196. doi: 10.1191/1352458504ms997oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oreja-Guevara C, Rovaris M, Iannucci G, Valsasina P, Caputo D, Cavarretta R, Sormani MP, Ferrante P, Comi G, Filippi M. Progressive gray matter damage in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(4):578–584. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schmierer K, Altmann DR, Kassim N, Kitzler H, Kerskens CM, Doege CA, Aktas O, Lunemann JD, Miller DH, Zipp F, Villringer A. Progressive change in primary progressive multiple sclerosis normal-appearing white matter: a serial diffusion magnetic resonance imaging study. Mult Scler. 2004;10(2):182–187. doi: 10.1191/1352458504ms996oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Agosta F, Absinta M, Sormani MP, Ghezzi A, Bertolotto A, Montanari E, Comi G, Filippi M. In vivo assessment of cervical cord damage in MS patients: a longitudinal diffusion tensor MRI study. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 8):2211–2219. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ciccarelli O, Catani M, Johansen-Berg H, Clark C, Thompson A. Diffusion-based tractography in neurological disorders: concepts, applications, and future developments. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(8):715–727. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pagani E, Bammer R, Horsfield MA, Rovaris M, Gass A, Ciccarelli O, Filippi M. Diffusion MR imaging in multiple sclerosis: technical aspects and challenges. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28(3):411–420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pagani E, Filippi M, Rocca MA, Horsfield MA. A method for obtaining tract-specific diffusion tensor MRI measurements in the presence of disease: application to patients with clinically isolated syndromes suggestive of multiple sclerosis. Neuroimage. 2005;26(1):258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lin F, Yu C, Jiang T, Li K, Chan P. Diffusion tensor tractography-based group mapping of the pyramidal tract in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28(2):278–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ciccarelli O, Toosy AT, Hickman SJ, Parker GJ, Wheeler-Kingshott CA, Miller DH, Thompson AJ. Optic radiation changes after optic neuritis detected by tractography-based group mapping. Hum Brain Mapp. 2005;25(3):308–316. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Simon JH, Zhang S, Laidlaw DH, Miller DE, Brown M, Corboy J, Bennett J. Identification of fibers at risk for degeneration by diffusion tractography in patients at high risk for MS after a clinically isolated syndrome. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24(5):983–988. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wilson M, Tench CR, Morgan PS, Blumhardt LD. Pyramidal tract mapping by diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging in multiple sclerosis: improving correlations with disability. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(2):203–207. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.2.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Reich DS, Smith SA, Zackowski KM, Gordon-Lipkin EM, Jones CK, Farrell JA, Mori S, van Zijl PC, Calabresi PA. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging analysis of the corticospinal tract in multiple sclerosis. Neuroimage. 2007;38(2):271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rocca MA, Pagani E, Absinta M, Valsasina P, Falini A, Scotti G, Comi G, Filippi M. Altered functional and structural connectivities in patients with MS: a 3-T study. Neurology. 2007;69(23):2136–2145. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000295504.92020.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rovaris M, Iannucci G, Falautano M, Possa F, Martinelli V, Comi G, Filippi M. Cognitive dysfunction in patients with mildly disabling relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: an exploratory study with diffusion tensor MR imaging. J Neurol Sci. 2002;195(2):103–109. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(01)00690-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vrenken H, Pouwels PJ, Geurts JJ, Knol DL, Polman CH, Barkhof F, Castelijns JA. Altered diffusion tensor in multiple sclerosis normal-appearing brain tissue: cortical diffusion changes seem related to clinical deterioration. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;23(5):628–636. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rovaris M, Riccitelli G, Judica E, Possa F, Caputo D, Ghezzi A, Bertolotto A, Capra R, Falautano M, Mattioli F, Martinelli V, Comi G, Filippi M. Cognitive impairment and structural brain damage in benign multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2008;71(19):1521–1526. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000319694.14251.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Benedict RH, Bruce J, Dwyer MG, Weinstock-Guttman B, Tjoa C, Tavazzi E, Munschauer FE, Zivadinov R. Diffusion-weighted imaging predicts cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007;13(6):722–730. doi: 10.1177/1352458507075592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Codella M, Rocca MA, Colombo B, Rossi P, Comi G, Filippi M. A preliminary study of magnetization transfer and diffusion tensor MRI of multiple sclerosis patients with fatigue. J Neurol. 2002;249(5):535–537. doi: 10.1007/s004150200060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rao SM, Leo GJ, Bernardin L, Unverzagt F. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. I. Frequency, patterns, and prediction. Neurology. 1991;41(5):685–691. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.5.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rovaris M, Judica E, Gallo A, Benedetti B, Sormani MP, Caputo D, Ghezzi A, Montanari E, Bertolotto A, Mancardi G, Bergamaschi R, Martinelli V, Comi G, Filippi M. Grey matter damage predicts the evolution of primary progressive multiple sclerosis at 5 years. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 10):2628–2634. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zivadinov R. Multiple Sclerois. Vol. 12. Madrid, Spain: 2006. Effect of Glatiramer Acetate on Diffusion Imaging in patients with MS; p. S991. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fox R. Effect of Natalizumab on Diffusion Imaging in patients with MS. New Orleans, USA: 2008. p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Frank LR. Anisotropy in high angular resolution diffusion-weighted MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2001;45(6):935–939. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tournier JD, Calamante F, Gadian DG, Connelly A. Direct estimation of the fiber orientation density function from diffusion-weighted MRI data using spherical deconvolution. Neuroimage. 2004;23(3):1176–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tuch DS. Q-ball imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52(6):1358–1372. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Assaf Y, Ben-Bashat D, Chapman J, Peled S, Biton IE, Kafri M, Segev Y, Hendler T, Korczyn AD, Graif M, Cohen Y. High b-value q-space analyzed diffusion-weighted MRI: application to multiple sclerosis. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47(1):115–126. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Assaf Y, Chapman J, Ben-Bashat D, Hendler T, Segev Y, Korczyn AD, Graif M, Cohen Y. White matter changes in multiple sclerosis: correlation of q-space diffusion MRI and 1H MRS. Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;23(6):703–710. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jensen JH, Helpern JA, Ramani A, Lu H, Kaczynski K. Diffusional kurtosis imaging: the quantification of non-gaussian water diffusion by means of magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53(6):1432–1440. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Falangola MF, Jensen JH, Babb JS, Hu C, Castellanos FX, Di Martino A, Ferris SH, Helpern JA. Age-related non-Gaussian diffusion patterns in the prefrontal brain. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28(6):1345–1350. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]