Summary

FADD is a common adaptor shared by several death-receptors (DRs) for signaling apoptosis through recruitment and activation of caspase 81-3. DRs are essential for immune homeostasis, but dispensable during embryogenesis. Surprisingly, FADD−/− mice die in utero4-5 and conditional deletion of FADD leads to impaired lymphocyte proliferation6-7. How FADD regulates embryogenesis and lymphocyte responses has been a long standing enigma. FADD could directly bind to RIP1, a serine/threonine kinase which mediates both necrosis and NF-κB activation. Here we show that FADD−/− embryos contain elevated levels of RIP1 and exhibit massive necrosis. To investigate potential in vivo functional interaction between RIP1 and FADD, null alleles of RIP1 were crossed into FADD−/− mice. Strikingly, RIP1 deficiency allowed normal embryogenesis of FADD−/− mice. Conversely, the developmental defect of RIP1−/− lymphocytes was partially corrected by FADD deletion. Furthermore, RIP1 deficiency fully restored normal proliferation in FADD−/− T cells but not in FADD−/− B cells. FADD−/−RIP1−/− double knockout (DKO) T cells are resistant to death induced by Fas or TNFα and display reduced NF-κB activity. Therefore, our data demonstrate an unexpected cell type-specific interplay between FADD and RIP1, which is critical for the regulation of apoptosis and necrosis during embryogenesis and lymphocyte function.

Programmed cell death (PCD) including apoptosis and necrosis are fundamental biological processes that are essential during embryonic development and for homeostasis in somatic tissues. DRs can signal apoptotic cell death when engaged by their cognate ligands8. This extrinsic death pathway requires the adaptor protein FADD that couples the signal generated by DRs to the apical caspase 83,9-10. The resulting activation of caspase 8 triggers a battery of downstream caspases, leading to apoptosis. Recently, DRs were shown to induce necrosis-like cell death in the presence of caspase inhibitors11-12. DR-induced necrosis is blocked in cells lacking the protein serine/threonine kinases RIP1 and RIP311-15. FADD and RIP1 play indispensable roles in development, as FADD−/− mice die during midgestation stages4-5, and RIP1−/− mice die at birth16. Whereas the developmental defect in RIP1−/− mice is presumably due in part to defective NF-κB activation and increased cell death17, the mechanism that underlies the developmental defect of FADD−/− mice has remained elusive.

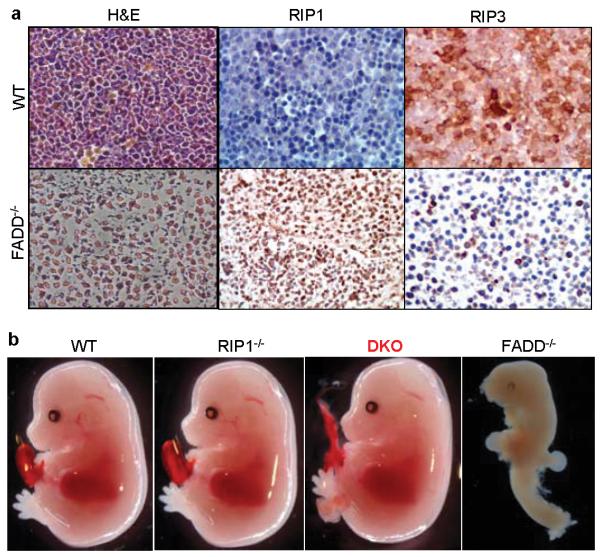

Developmental retardation of FADD−/− mouse is apparent at embryonic day (E)11.5 to 13.5 (Fig. S1a-b). Histological analysis revealed extensive necrotic cell death and cell loss in FADD−/− embryos (Fig. 1a). Absence of FADD sensitizes human Jurkat T lymphoma cells to tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-induced necrosis11-12. Furthermore, FADD−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were hypersensitive to reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced necrosis18. In contrast, necrosis induced by ROS was blocked in RIP1−/− MEF cells. Examination of wild type (WT) E12.5 embryos showed that RIP1 was expressed at low levels while RIP3 was readily detected in multiple tissues including the nervous system, heart and lung (Fig. 1a and S2). Interestingly, RIP1 expression is highly elevated in FADD−/− embryos (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, punctate RIP3 staining was observed in cells of FADD−/− embryos, which is indicative of RIP3 aggregation and activation14. These results indicate that induction of RIP1 expression might play a role in the necrosis observed in FADD−/− embryos.

Figure 1. RIP1 deficiency rescues FADD−/− mice from embryonic necrosis and lethality.

a, FADD−/− embryos exhibit massive necrosis and altered RIP1 and RIP3 expression. E12.5 wild type (WT, top panels) or FADD−/− embryos (bottom panels) were fixed in formalin. Left panels of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining show extensive cell loss and pyknotic nuclei in the FADD−/− fetal liver. Middle and right panels indicate staining for RIP1or RIP3. b, E14.5 DKO embryos appear normal, contrasting the defective FADD−/− embryos.

To investigate a potential in vivo molecular interplay between FADD- and RIP1-mediated signaling, we crossed the RIP1 knockout alleles into FADD−/− mice. Strikingly, FADD−/−RIP1−/− double knockout (DKO) embryos were detected at E14.5 at the expected Mendelian frequencies (Table 1, Fig. 1b and S1c-f). In sharp contrast to the highly deformed E14.5 FADD−/− embryos, E14.5 DKO embryos were indistinguishable from wild type control embryos (Fig. 1b). DKO embryos of normal morphology were also found at later gestation stages E15.5, E16.5, E17.5 and E18.5 at the expected Mendelian frequencies (Fig. S1c and Table 1). Importantly, live DKO neonates were also detected at birth (Fig. S1d). No FADD−/− embryos were detected at E15.5 or later stages. Histological examination did not reveal obvious defects in RIP1−/− and DKO E18.5 embryos (Fig. S3). Postnatal monitoring was performed to determine the survival of DKO mice. Among the 104 postnatal mice analyzed (>0 day, Table 1), 30 died within 4 days after birth, which contain 6 DKO and 19 RIP1−/− genotypes. No death was observed after postnatal day 4 and DKO mice were not present in the remaining 74 mice that survive beyond 3 weeks (Table 1). These results demonstrate that RIP1 deficiency fully restore embryonic development of FADD−/− mice. However, loss of FADD does not prevent neonatal lethality of RIP1−/− mice. ROS is an important effector mechanism for necrotic cell death. FADD−/− MEFs were hypersensitive to ROS-induced death (Fig. S4a-b). In contrast, RIP1−/− MEFs were highly resistant to ROS-induced necrosis18. Addition of the RIP1-specific inhibitor necrostatin-1 (Nec-1)19 greatly reduced ROS-hypersensitivity in FADD−/− MEFs (Fig. S4a-b). Importantly, DKO MEFs were resistant to ROS-induced death. Collectively, these results indicate that FADD deficiency primes embryonic cells to ROS- and RIP1-dependent necrosis, which might cause embryonic lethality.

Table 1. Genetic analysis of FADD and RIP1 deficiency in mice.

Timed pregnancy analyses were set up to determine the frequencies of each genotype of offspring from intercrosses of FADD+/−RIP1+/− mice. The actual (shaded) and expected numbers of each or groups of genotypes were shown. Neonates were sacrificed and analyzed at birth (0 day) or monitored for survival for up to 6 month (>0 days). Numbers of DKO embryos or neonates were in bold. Postnatal RIP1−/− and DKO neonates (>0 days) died within 4 days after birth.

| Genotype | FADD | +/+ or +/− | +/+ or +/− | −/− | −/− | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| RIP1 | +/+ or +/− | −/− | +/+ or +/− | −/− | |||

| E14.5-18.5 embryos |

Actual | 102 | 45 | 17 | 14 | 178 | |

| Expected | 100 | 33 | 33 | 11 | |||

|

| |||||||

| At or after birth |

Day 0 | Actual | 26 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 31 |

| Expected | 17 | 6 | 6 | 2 | |||

|

|

|||||||

| >day 0 | Actual | 79 | 19 | 0 | 6 | 104 | |

| Expected | 59 | 20 | 20 | 7 | |||

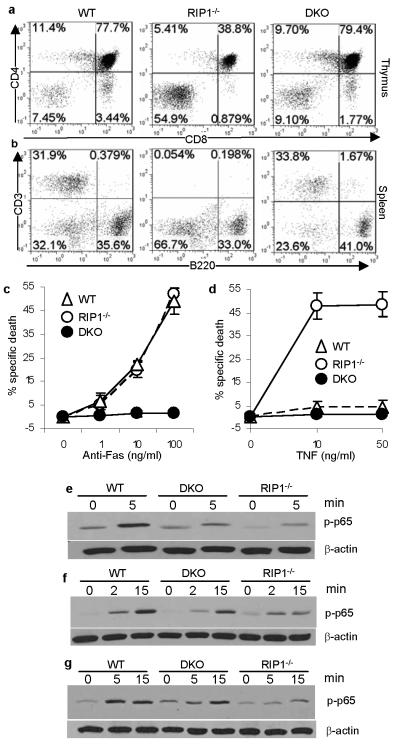

While important at early hematopoietic stages 20, FADD plays a minor role in post lineage commitment lymphopoiesis 4,6-7. Although RIP1−/− neonates contain normal thymocyte numbers16, RIP1−/− fetal liver cells failed to reconstitute the peripheral T cell compartment17. The rescue of embryonic development in DKO mice prompted us to examine whether a similar FADD-RIP1 interaction might regulate lymphocyte development. To this end, we adoptively transferred fetal liver cells containing hematopoietic progenitor cells into immunodeficient NSG recipient mice. In agreement with previous results17, NSG chimeras reconstituted with RIP1−/− fetal liver cells contained dramatically reduced CD4+CD8+ double positive immature and CD4+ or CD8+ single positive mature thymocytes (Fig. 2a). In contrast, the thymic population profile of DKO fetal liver cell chimeras was similar to that of the wild type control thymus (Fig. 2a). Reconstitution of the peripheral lymphoid compartment by DKO fetal liver cells was apparent, as indicated by the spleen sizes of the recipients of DKO fetal liver cells, which was similar to the size of the control spleens receiving wild type fetal liver cells (Fig. S5a). In contrast, the spleen of RIP1−/− chimeras was smaller than that of wild type or DKO chimeras. Flow cytometric analyses showed that RIP1−/− chimeras contained few CD3+ T cells in the periphery (Fig. 2b and S5b-c). In contrast, DKO chimeras contained significantly higher numbers of T cells in the spleen, lymph nodes, and blood (Fig. 2b and S5b-c). Similarly, FADD deficiency partially rescued RIP1−/− B cell development (Fig. S5c). RIP1−/− thymocytes were readily killed by treatments with anti-Fas antibodies or TNF (Fig. 2c-d). Interestingly, DKO thymocytes were highly resistant to these death stimuli. Although FADD deficiency fully reversed the hypersensitivity to Fas- and TNFα-induced killing, it only partially corrected the NF-κB activation defect in RIP1−/− T cells, B cells and MEFs (Fig. 2e-g). These results suggest that the partial rescue of lymphocyte development in the DKO chimeras is due to inhibition of FADD-mediated apoptosis rather than rescue of NF-κB activation.

Figure 2. FADD deficiency partially corrects the RIP1−/− T cell developmental defect by blocking apoptosis.

Lymphocytes (a-b) in the chimeras of the indicated genotypes were analyzed. E18.5 fetal thymocytes of the indicated genotypes were treated with anti-Fas antibodies (c) or TNFα (d) and death responses determined 12 hours post stimulation. Error bars represent mean ± SEM of triplicates. T cells (e) and B cells (f) from NSG chimeras of the indicated genotypes were stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies or with LPS, respectively. MEFs were stimulated with TNFα (g). NF-κB activation was indicated by the induction of p65 phosphorylation. β-actin, loading controls.

Although T cell-specific deletion of FADD had no effect on thymic development, the resulting mature FADD−/− T cells were highly defective in TCR-induced proliferation6 (Fig. 3a). When compared to FADD−/− and WT controls, DKO T cells stimulated through the TCR/CD28 exhibited a remarkable rescue in their proliferative responses (Fig. 3a and Table S1a). When transferred to TCRαβ−/− hosts, DKO T cells were functionally competent to expand and produce IFNγ in response to challenge with Pichinde virus (PV) (Fig. 3b). Acute CD8+ T cell responses to the immunodominant epitope NP38 and subdominant epitope NP205 were similar between WT and DKO donor cells (Fig. 3b). Moreover, challenge of wild type hosts adoptively transferred with DKO lymphocytes with lymphocytic choriomenigitis virus (LCMV) showed that the DKO T cells could generate a productive anti-viral response to the immunodominant epitope NP396 (Fig. S6a). Collectively, these results indicate that RIP1-dependent necrosis underlies the defective proliferation in FADD−/− T cells and that inactivation of RIP1 restores the proliferative capacity of FADD−/− T cells.

Figure 3. RIP1 deficiency rescues the FADD−/− T cell proliferation defect.

a, T cells of the indicated wild type and chimera genotypes were stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies. Proliferation was measured by [3H]-thymidine incorporation. b, Splenocytes of the indicated genotypes were transferred into TCRαβ−/− hosts and challenged with Pichinde virus (PV). Acute responses of the donor CD8 T cells to the indicated epitopes were determined. Anti-CD3 antibodies were used as control. c, B cells of the indicated genotypes were stimulated with LPS and proliferation was measured as in (a). Results shown (a and c) are mean ± SEM of triplicates.

Although FADD does not play a significant role in BCR- or CD40-induced proliferation responses, it is required for TLR3 and TLR4 signaling in B cells7. Consistent with these observations, WT, RIP1−/−, FADD−/− and DKO B cells responded similarly to stimulation with anti-IgM or anti-CD40 antibodies (Fig. S6b and data not shown). In contrast to the rescue of T cell proliferation, DKO B cells remained defective in proliferative responses to the TLR3 and TLR4 agonists poly IC and LPS, respectively (Fig. 3c, S6c and Table S1b). The differential effect of RIP1 deletion on FADD−/− T and B cell proliferation was confirmed with the RIP1-specific inhibitor Nec-1 (Fig. S6d-e). Although caspase inhibition did hamper LPS-induced B cell proliferation (Fig. S7a-b), RIP1 cleavage, which inactivates the pro-necrotic activity of RIP1, was only observed in TCR-treated T cells, but not LPS-induced B cells or ROS-treated MEFs (Fig. S8a-c). Therefore, the FADD-RIP1 axis is preferentially required for controlling proliferation in T cells, but not in B cells.

The current study demonstrates that absence of RIP1 restored normal embryogenesis of FADD−/− mice, and FADD deficiency partially corrects the developmental defect in RIP1−/− T cells. This finding provides compelling genetic evidence that a critical in vivo role for FADD during embryogenesis is to inhibit RIP1-mediated necrosis. In T cells, RIP1 is required to help suppress FADD-mediated apoptosis. Interestingly, caspase 8−/− mice exhibited embryonic and T cell defects similar to that of FADD−/− mice4-5,21. Moreover, Nec-1 rescued the proliferative defect of caspase 8−/− and FADD−/− T cells22-23. Hence, FADD and caspase 8 likely act in concert to keep RIP1-mediated necrosis in check by cleavage and inactivation of RIP1. Such regulatory mechanism is crucial to ensure proper embryogenesis and to prevent abortive expansion of T cells during immune responses. Our results also reveal an unexpected role for RIP1 to keep FADD-mediated apoptosis at bay during T cell development. This regulation is not entirely dependent on RIP1-mediated activation of the NF-κB pathways, unlike that proposed previously16-17. The reduced NF-κB activation had no major effect on DKO T cell proliferations. In addition to lymphocytes, impairment of the NF-κB pathway is also present in RIP1−/− and DKO MEFs and likely other cell types, which might lead to postnatal lethality as seen in RIP1−/− and DKO mice. In summary, our results reveal a complex functional interaction between FADD and RIP1 that is context- and cell type-dependent.

Methods summary.

Heterozygous FADD+/− mutant mice have been described4. Heterozygous RIP1+/− mutant mice16 were provided by Dr. M. Kelliher and crossed into FADD+/− mice. Timed pregnancy was set up with the resulting FADD+/−RIP1+/− mouse intercrosses. Embryos were isolated and genotyped by PCR using tissue genomic DNA templates and confirmed by western blots. Fetal liver cells were isolated from E14.5 embryos and adoptively transferred into irradiated (200 RAD) NSG (NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ) mice purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. All animal studies were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees. Ten to 12 weeks post transfer, cells were isolated from the indicated organs and were analyzed by flow cytometry. T cells and B cells were purified from the spleen and lymph nodes by high-speed sorting and proliferative responses were analyzed as described previously6-7. FADD−/− mutant T cells and B cells were isolated by sorting from T cell-specific and B cell-specific FADD−/− mice as described previously6-7. Western blotting was performed according to standard protocols. For embryonic cell death assays, primary MEFs were prepared following the NIH 3T3 protocol. FADD−/− MEFs were prepared from E8.5 embryos and DKO MEFs from E14.5MEFs. MEF cells were cultured in complete DMEM to 80% confluence, and treated with 0.5 mM H2O2 with or without Nec-1 (50 μM) for 12 h, and cell death was determined by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry. Images were taken by using a Nikon inverted light microscope. For virus infections, after adoptive transfer of lymphocytes, mice were challenged with 5 × 104 pfu of LCMV or 1 × 107 pfu of PV. Peptide specific CD8 T cell responses were measured 8 days after infection by intracellular IFNγ staining.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. M. Kelliher for providing RIP1+/− mice, Drs. Steve Rosenberg, S. Waggoner, R. Welsh, V. Vanguri and Y. Liu for advice and technical assistance, Dr. Xin Lin for helpful discussions and suggestions, Dr. Catherine E. Calkins and Kathy Reinersmann for critical reading of the manuscript, and Dr. Zhijiu Zhong for help with histology analysis. This study was supported in part by NIH grants, CA95454, AI083915, and AI076788 awarded to J.Z. and AI083497 awarded to F.C.; a W. W. Smith Charitable Trust grant, a TJU Enhancement grant, and a CONCERN Foundation grant awarded to J.Z. F.C. is a member of the UMass DERC (DK32520) and also supported in part by an NIH grant (AI017672).

Appendix

Online-only Methods

Reagents

Antibodies were purchased from the following vendors: RIP1 (BD Pharmingen), RIP3 (ProSci), caspase 8 (Axxora), phospho-p65 (Cell Signaling), CD3 (BD Biosciences), CD28 (BD Biosciences), and strepavidin (BD Biosciences). Antibodies used in immunophenotyping were purchased from BD Biosciences or eBioscience or BioLegend. Rabbit anti-FADD antibody were generated in house. Necrostatin-1 and zVAD-fmk were purchased from Axxora.

Mouse genetic analysis

Mating of FADD+/−RIP1+/− double heterozygous mice was set up at evening. Female mice were examined in the early morning and embryos were designated E0.5 on the day the vaginal plug was detected. E11.5 to E18.5 embryos were isolated from pregnant mice and genomic DNA was extracted from embryo tissues upon digestion with protease K in an SDS containing lysis buffer. Genotyping was performed by PCR using allele-specific primers. 5′-TGCGCCGACACGATCTACTG-3′ and 5′-AGCTGTAGGCTTGTCAGGGTGTTTC -3′ were used for the detection of the FADD wild type allele; 5′-ACTGTAGTGCCCAGCAGAGACCAGC -3′ and 5′-CGCTCGGTGTTCGAGGCCACACGC -3′ for the FADD knock out allele; 5′-TGTGTCAAGTCTCCCTGCAG-3′ and 5′-CACGGTCCTTTTGCCCTG-3 for the RIP1 WT allele; and 5′-CTGCTAAAGCGCATGCTC-3′ and 5′-CACGGTCCTTTTGCCCTG-3 for the RIP1 knock out allele. Presence and absence of the FADD and RIP1 protein was confirmed by western blotting using anti-FADD and anti-RIP1 (BD Pharmingen) antibodies. For postnatal analysis, pregnant females were closely monitored around the time of delivery (after 18.5 days post coitum), by checking at least twice daily. Neonates were either euthanized at birth for genotyping or monitored for survival up to 6 months. Dead mice were immediately removed for genotyping.

Histological analysis and immunohistochemistry

Embryos were fixed in 10% buffered formalin overnight. After dehydration in 70% and increasing concentrations of ethanol, embryos were embedded in paraffin. Embryo sections were prepared and standard H&E staining performed. Immunohistochemistry was performed using anti-RIP1 (H207, Santa Cruz) and anti-RIP3 (ProSci) antibodies at 1:200 dilution, followed by incubation with ImmPress anti-rabbit peroxidase (Vector Lab). Signals were developed with 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine (5 min) and Enhancer (DAKO) for 2 min. Sections were then counterstained with hematoxylin.

Lymphocyte immunophenotyping

Lymphocytes were isolated from spleen, thymus, lymphocyte nodes and blood. Red blood cells were lysed using the ACK lysis buffer and single cell suspension was prepared, stained for cell surface markers following standard protocols, and data acquisition was performed using a Coulter XL cytometer. Flow cytometric data were analyzed with the FlowJo software (Treestar, San Carlos, CA).

Cell death analysis

Thymocytes were isolated from the E18.5 embryos and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. Cells were then seeded (1 × 105/well) into 96-well flat bottom plates with various concentrations of anti-Fas antibodies (Jo2; BD Pharmingen) or recombinant mouse TNF-α (Biosource/Invitrogen) in the presence of 30 μg/ml cycloheximide (Sigma-Aldrich). Cell death was determined by propidium iodide (PI) staining and flow cytometry 12-16 h post stimulation.

Lymphocyte activation and western blot analysis

Peripheral T cells and B cells were purified from the spleen and lymphoid nodes using EasySep Isolation reagent (StemCell Technologies) or high speed sorting. Purified T cells were stimulated with biotinylated anti-CD3 antibodies (10μg/ml) and anti-CD28 antibodies (2 μg/ml) by crosslinking with streptavidin (10 μg/ml) for the indicated times at 37 °C. In some experiments, cells were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies. Purified B cells were stimulated with 10 μg/ml LPS for the indicated times at 37°C. Where indicated, cells were pre-incubated with 50 μM zVAD-fmk or 10 μM necrostatin-1 before stimulation. Cells were washed once in ice cold PBS and lysed with ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Protein was separated on 10% SDS/PAGE then transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane, blocked with 5% milk in TBST, incubated overnight at 4°C with primary Abs. Blots were washed 3 times with TBST and incubated in HRP-conjugated second antibody per manufacturer’s recommendations. The Western Lighting Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus (PerkinElmer) or ThermoScientific West Pico chemiluminescence reagents were used to detect signals on x-ray films (Kodak).

Cell culture and proliferation assays

Purified T cells and B cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 1mM glutamine, 5 μM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and 10% FBS (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT). Cells were cultured at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. B cells were cultured with the indicated concentrations of LPS, poly IC (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), goat-anti-mouse IgM (F(ab’)2 μ chain, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for 48 h. T cells were stimulated with various concentration of plate-bound anti-CD3 antibodies in 96 well plates in the presence of anti-CD28 (200ng/ml) antibodies for 48 hours. Incorporated [3H]-thymidine was measured using a Wallac beta counter (PerkinElmer, Wellesley, MA). To determine cell division, cell proliferation measured by dilution of CellTracer Violet dye (Invitrogen) was performed as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Virus infection

Ten to twenty millions wild type or DKO total splenocytes were injected via the tail vein to wild type Ly5.1 congenic hosts. For injection into TCRαβ−/− hosts, 2 × 106 cells were injected. Eighteen hours later, mice were infected with 5 × 104 pfu of lymphocytic choriomenigitis virus (Armstrong strain) or 1 × 107 pfu of Pichinde virus (strain AN3739) intraperitoneally. Eight days post-infection, splenocytes were isolated and stimulated with the indicated viral peptide antigens for 5 hours or anti-CD3 antibody for 4 hours. Production of IFNγ was examined by intracellular FACS staining on a LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Footnotes

Supplementary information includes 8 figures, 1 supplemental table and Methods

References

- 1.Boldin MP, et al. A novel protein that interacts with the death domain of Fas/APO1 contains a sequence motif related to the death domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:7795–7798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.14.7795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chinnaiyan AM, O’Rourke K, Tewari M, Dixit VM. FADD, a novel death domain-containing protein, interacts with the death domain of Fas and initiates apoptosis. Cell. 1995;81:505–512. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang J, Winoto A. A mouse Fas-associated protein with homology to the human Mort1/FADD protein is essential for Fas-induced apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:2756–2763. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang J, Cado D, Chen A, Kabra NH, Winoto A. Absence of Fas-mediated apoptosis and T cell receptor-induced proliferation in FADD-deficient mice. Nature. 1998;392:296–300. doi: 10.1038/32681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeh W-C, et al. FADD: essential for embryo development and signaling from some, but not all, inducers of apoptosis. Science. 1998;279:1954–1958. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5358.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, et al. Conditional Fas-Associated Death Domain Protein (FADD):GFP Knockout Mice Reveal FADD Is Dispensable in Thymic Development but Essential in Peripheral T Cell Homeostasis. J. Immunol. 2005;175:3033–3044. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imtiyaz HZ, et al. The Fas-associated death domain protein is required in apoptosis and TLR-induced proliferative responses in B cells. J. Immunol. 2006;176:6852–6861. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagata S. Apoptosis by death factor. Cell. 1997;88:355–365. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81874-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boldin MP, Goncharov TM, Goltsev YV, Wallach D. Involvement of MACH, a novel MORT1/FADD-interacting protease, in Fas/APO-1-and TNF receptor-induced cell death. Cell. 1996;85:803–815. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81265-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muzio M, et al. FLICE, a novel FADD-homologous ICE/CED-3-like protease, is recruited to the CD95 (Fas/APO-1) death-inducing signaling complex. Cell. 1996;85:817–827. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holler N, et al. Fas triggers an alternative, caspase-8-independent cell death pathway using the kinase RIP as effector molecule. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:489–495. doi: 10.1038/82732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan FK-M, et al. A Role for Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor-2 and Receptor-interacting Protein in Programmed Necrosis and Antiviral Responses. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:51613–51621. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305633200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho YS, et al. Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell. 2009;137:1112–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He S, et al. Receptor interacting protein kinase-3 determines cellular necrotic response to TNF-alpha. Cell. 2009;137:1100–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang DW, et al. RIP3, an energy metabolism regulator that switches TNF-induced cell death from apoptosis to necrosis. Science. 2009;325:332–336. doi: 10.1126/science.1172308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelliher MA, et al. The death domain kinase RIP mediates the TNF-induced NF-κB signal. Immunity. 1998;8:297–303. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80535-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cusson N, Oikemus S, Kilpatrick ED, Cunningham L, Kelliher M. The Death Domain Kinase RIP Protects Thymocytes from Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor Type 2-induced Cell Death. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196:15–26. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen HM, et al. Essential roles of receptor-interacting protein and TRAF2 in oxidative stress-induced cell death. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5914–5922. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5914-5922.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Degterev A, et al. Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic potential for ischemic brain injury. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:112–119. doi: 10.1038/nchembio711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenberg S, Zhang H, Zhang J. FADD deficiency impairs early hematopoiesis in the bone marrow. J. Immunol. 2011;186:203–213. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varfolomeev EE, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse caspase 8 gene ablates cell death induction by the TNF receptors, Fas/Apo1, and DR3 and is lethal prenatally. Immunity. 1998;9:267–276. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80609-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ch’en IL, et al. Antigen-mediated T cell expansion regulated by parallel pathways of death. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105:17463–17468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808043105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osborn SL, et al. Fas-associated death domain (FADD) is a negative regulator of T-cell receptor-mediated necroptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:13034–13039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005997107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.