Summary

A hallmark of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis life cycle is the pathogen’s ability to switch between replicative and non-replicative states in response to host immunity. Transcriptional profiling by qPCR of ~50 M. tuberculosis genes involved in central and lipid metabolism revealed a re-routing of carbon flow associated with bacterial growth arrest during mouse lung infection. Carbon rerouting was marked by a switch from metabolic pathways generating energy and biosynthetic precursors in growing bacilli to pathways for storage compound synthesis during growth arrest. Results of flux balance analysis using an in silico metabolic network were consistent with the transcript abundance data obtained in vivo. Similar transcriptional changes were seen in vitro when M. tuberculosis cultures were treated with bacteriostatic stressors under different nutritional conditions. Thus, altered expression of key metabolic genes reflects growth rate changes rather than changes in substrate availability. A model describing carbon flux rerouting was formulated that (i) provides a coherent interpretation of the adaptation of M. tuberculosis metabolism to immunity-induced stress and (ii) identifies features common to mycobacterial dormancy and stress responses of other organisms.

Keywords: Central metabolism, metabolic switch, lipid biosynthesis, triacylglycerol

Introduction

Tubercle bacilli switch between replicative (growth) and non-replicative (dormancy) states in response to the host environment. Immunity-induced cessation of bacterial growth leads to a chronic, asymptomatic infection that is maintained by persisting tubercle bacilli. When host immunity falters, tubercle bacilli can resume growth and cause disease. Dormant bacilli present a formidable challenge to tuberculosis control, because they are much less susceptible to antibacterial drugs than growing bacilli (Zhang, 2004). Thus, a molecular understanding of events occurring during the transition from growth to dormancy is important for identifying critical targets for new tuberculosis control strategies.

The metabolism of M. tuberculosis during infection has been an area of intense interest since the origins of tuberculosis research. Seminal experiments showed that the tubercle bacillus, which is metabolically flexible (Wheeler, 1994), preferentially utilizes fatty acids as carbon and energy source during murine infection (Bloch & Segal, 1956). This preferential utilization is likely due to increased availability of lipids in the infected host cell (Russell et al., 2009) and is reflected in the M. tuberculosis genome as a significant enrichment for fatty acid degradation genes (Cole et al., 1998). Moreover, genes involved in fatty acid utilization (glyoxylate shunt: icl; gluconeogenesis: glpX and pckA) are required for growth and persistence in vivo (Sassetti & Rubin, 2003, Collins et al., 2002, Munoz-Elias & McKinney, 2005, Liu et al., 2003, Marrero et al., 2010). Some of these genes (icl, pckA) are also upregulated in non-growing bacilli during mouse infection (McKinney et al., 2000, Schnappinger et al., 2003, Timm et al., 2003). These observations led to the proposal that M. tuberculosis switches its carbon source from sugars to fatty acids during the persistent phase of infection (Bishai, 2000, Honer zu Bentrup & Russell, 2001, Timm et al., 2003). However, similar metabolic changes are observed in the stress response of other organisms, such as sporulation in yeast (Cortassa et al., 2000), where they are linked to the rerouting of carbon flow toward formation of storage compounds. Indeed, tubercle bacilli obtained from sputum of tuberculosis patients are rich in triacylglycerol (TAG) (Garton et al., 2008), a common storage compound in Actinobacteria (Alvarez & Steinbuchel, 2002). Therefore, it has been unclear whether the metabolic changes in the tubercle bacillus during infection reflect implementation of a developmental program toward persistence or an adaptive response to changed nutritional conditions.

In the present work we examined the response of M. tuberculosis metabolism to the stress encountered during infection with a multi-scale approach that included studies in vivo (mouse infection), in silico, and in vitro (broth culture). We interrogated two aspects of carbon metabolism of tubercle bacilli. One is central metabolism, which provides energy, reducing power, and biosynthetic precursors. The other is the biosynthesis of major lipids, such as mycobacterial cell wall components, which constitute a sink for energy and biosynthetic precursors (Brennan, 2003), and triacylglycerol (TAG), which is a storage lipid (Brennan, 2003, Garton et al., 2008, Low et al., 2009). Transcription profiling of tubercle bacilli during infection of mouse lungs led to a metabolic model in which carbon flow redistributes at the phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP)/pyruvate-oxaloacetate (OAA) node as growth stops, thereby switching from the generation of energy and biosynthetic precursors to the synthesis of storage compounds. The in vivo data provided conditions to perform in silico simulations of metabolic flux patterns associated with M. tuberculosis growth arrest using a genome-scale metabolic network of the tubercle bacillus (Beste et al., 2007). We found that metabolic fluxes (i) were largely consistent with the transcription profiles of M. tuberculosis central metabolism genes seen during mouse infection and (ii) predicted that utilization of different carbon sources would result in similar flux solutions. This prediction was tested in vitro using M. tuberculosis cultures subjected to bacteriostatic stress in media containing different carbon sources. We found that transcriptional changes of key metabolic genes during M. tuberculosis growth arrest were independent of stress signal and carbon source. Thus, M. tuberculosis persistence shares critical metabolic features with bacterial and yeast sporulation, plant seed formation, and animal hibernation. Our results led to the novel view that the metabolic changes of M. tuberculosis are part of a developmental decision rather than a response to changed nutrient availability.

Results and Discussion

To assess carbon flow distribution during the establishment of persistent infection, we used a model of respiratory infection of mice in which M. tuberculosis replicates in the lung for about 20 days, and then it enters a state in which bacterial numbers stabilize due to expression of acquired cell-mediated immunity (Shi et al., 2003, Shi et al., 2005). We measured changes of bacterial transcript abundance in the mouse lung using qPCR with samples taken at multiple times post-infection (day 12 through day 100). We then expressed the data as a ratio of abundance at each given time point relative to that measured at day 12 (mid-log growth).

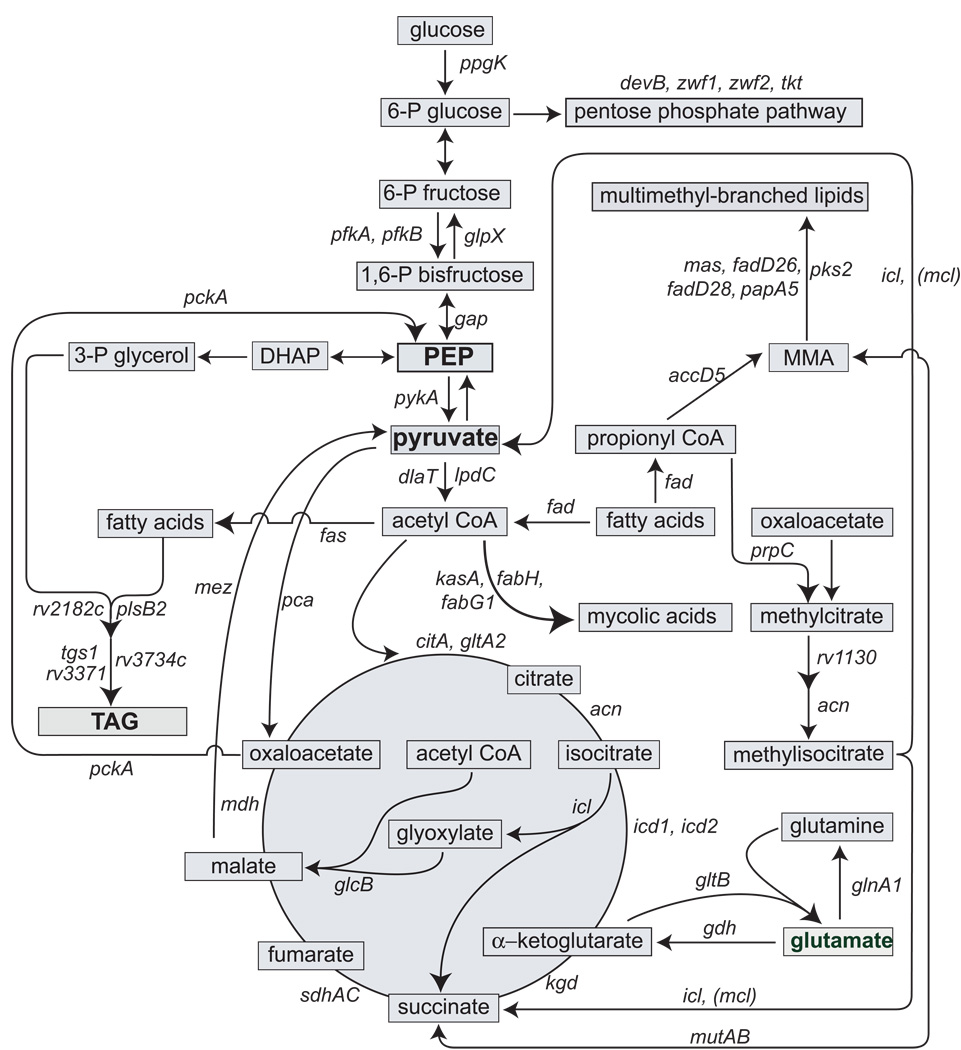

The in vivo data are presented below in two sections, (i) central metabolism and fatty acid catabolism and (ii) lipid biosynthesis. Of the lipid biosynthetic genes, we focused on those involved in the synthesis of the major storage compound TAG (Garton et al., 2008) and of the major components of the mycobacterial cell wall, such as mycolic acids and multimethyl-branched lipids. At the end of each section, the data are interpreted through a metabolic model of M. tuberculosis growth arrest. A scheme showing the main pathways of carbon metabolism and the representative genes in each pathway selected for analysis is presented in Fig. 1 and SI Table 1.

Fig. 1. Pathways and genes in central metabolism and lipid metabolism in M. tuberculosis analyzed in the present work.

A schematic representation of the metabolic pathways of M. tuberculosis interrogated by qPCR is shown. In each pathway, gene names and/or Rv numbering (Cole et al., 1998) are indicated. Key intermediates and storage compounds are shown in bold. Abbreviations: PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate, TAG, triacylglycerol. Fatty acid β-oxidation: fadE5 (Rv0244c) and fadE23 (Rv3140), acyl-CoA dehydrogenase; fadA4 (Rv1323), acyl-CoA acetyltransferase; fadB (Rv0860), fatty acid oxidation protein. Glycolysis: ppgK (Rv2702), glucokinase; pfkA (Rv3110c) and pfkB (Rv2029c), phosphofructose kinase; gap (Rv1436), glyceraldehyde 3-P dehydrogenase; pykA (Rv1617), pyruvate kinase; dlaT (Rv2215) and lpdC (Rv0462), E2 and E3 components of pyruvate dehydrogenase. PPP: devB (Rv1445), 6-phosphogluconolactonase; zwf1 (Rv1121) and zwf2 (Rv1447c), glucose 6-P 1-dehydrogenase; tkt (Rv1449c), transketolase. TCA cycle: citA (Rv0889c), citrate synthase II; gltA2 (Rv0896), citrate synthase I; acn (Rv1475), aconitase; icd1 (Rv3339c) and icld2 (Rv0066c), isocitrate dehydrogenase; kgd (Rv1248c), α-ketoglutarate decarboxylase; sdhA (Rv3318), flavoprotein of succinate dehydrogenase; sdhC (Rv3316), cytochrome B-556 of succinate dehydrogenase; mdh (Rv1240), malate dehydrogenase. Glyoxylate shunt: icl (Rv0467), isocitrate lyase; glcB (Rv1837c), malate synthase. Methylcitrate cycle and methylmalonyl pathway: prpDC (Rv1130–1131), methylcitrate dehydratase and methylcitrate synthase, respectively; mutAB (Rv1942–1943), methylmalonyl-CoA mutase, small and large subunit. Gluconeogenesis: mez (Rv2332), malic enzyme; pckA (Rv0211), PEP carboxykinase; glpX (Rv1099c), fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase. Glutamate and glutamine synthesis: gltB (Rv3859), glutamate synthase (large subunit); glnA1 (Rv2220), glutamine synthetase; gdh (Rv2476c), glutamate dehydrogenase. TAG synthesis: plsB2 (Rv2482c), glycerol 3-P acyltransferase; Rv2182c, 1-acylglycerol 3-P O-acyltransferase; tgs1 (Rv3130c), TAG synthase; Rv3734c and Rv3371, TAG synthase. Mycolic acid synthesis: fas (Rv2524c), fatty acid synthase; fabH (Rv0533c), β-ketoacyl-AcpM synthase III; kasA (Rv2245), β-ketoacyl-AcpM synthase; fabG1 (Rv1483), β-ketoacyl-AcpM reductase. Multimethyl-branched lipid synthesis: accD5 (Rv 3280), PropCoA carboxylase β chain 5; mas (Rv2940), mycocerosic acid synthase; fadD26 (Rv2930), fatty-acid-CoA ligase; fadD28 (Rv2941), fatty-acid-CoA synthetase; papA5 (Rv2939), conserved polyketide synthase; pks2 (rv3825c), conserved polyketide synthase.

Central metabolism

Glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP)

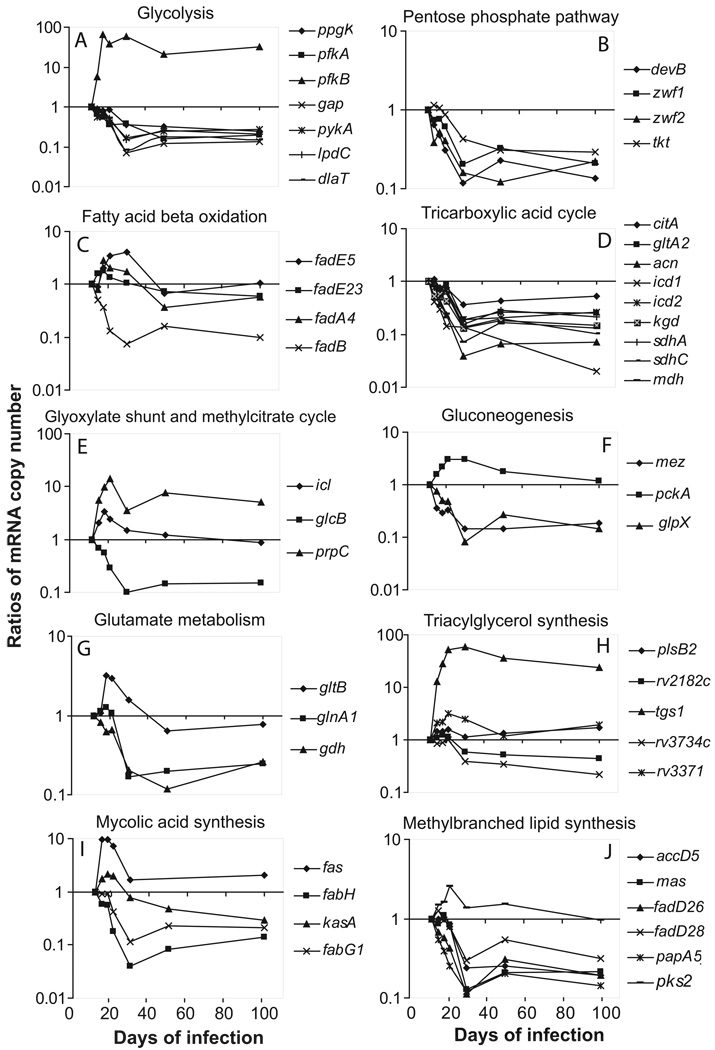

Glucose is oxidized through glycolysis and, to a lesser extent, through the PPP (Jayanthi Bai et al., 1975). Glycolysis yields central metabolites such as PEP, pyruvate, and acetyl-CoA (AcCoA). PPP generates reducing equivalents for reductive biosynthetic reactions and provides ribose 5-P for nucleotide synthesis. Enumeration of transcripts encoding key glycolytic and PPP enzymes of M. tuberculosis showed that most transcripts were down-regulated during growth arrest relative to log growth (up to 15-fold decrease at day 30 of infection) (Fig. 2A–B; SI Table 2). However, two genes encoding phosphofructokinase differed in their response. pfkA was downregulated, while pfkB was strongly up-regulated: the number of pfkB transcripts peaked at day 18 (65-fold) and remained high for the remainder of infection (>30-fold at day 100) (Fig. 2A). Since pfkB is a member of the devR/dosR regulon (Voskuil et al., 2003), pfkB upregulation agrees with our previous observation that DevR/DosR-regulated genes are induced by expression of immunity in the mouse lung (Shi et al., 2003).

Fig. 2. Changes in mRNA levels of M. tuberculosis genes involved in central metabolism and lipid metabolism during mouse lung infection.

Lungs were harvested from 3 to 4 mice at multiple time points (up to day 100) post-infection, as indicated. Total RNA was extracted and qPCR enumeration of bacterial transcripts was performed. Bacterial mRNA copy numbers were normalized to 16S rRNA. Results are shown as ratios of the mean of normalized mRNA copy numbers at each time point relative to the mean of normalized copy numbers at day 12 post-infection. Raw data (means and SD) for each time point are shown in SI Table 2. Each panel represents the indicated metabolic pathways.

Sugars are presumably scarce during infection, and most glycolytic reactions can be reversibly utilized for gluconeogenesis. Thus, the observed downregulation of most glycolytic genes and the strong upregulation of pfkB, whose product catalyzes the irreversible and rate-limiting reaction of glycolysis, should result in decreased intracellular concentration of C6 sugars. This scenario is consistent with bacillary growth arrest, since C6 sugars may serve as precursors for macromolecular biosynthesis during growth, and they would not be needed by non-growing bacilli.

Fatty acid degradation

Fatty acids, which are the main source of carbon and energy for M. tuberculosis during infection, are primarily catabolized via successive rounds of β-oxidation. Even-chain fatty acids are degraded to AcCoA, and odd-chain fatty acids are degraded to both AcCoA and propionyl-CoA (PropCoA). It is likely that tubercle bacilli catabolize a wide range of fatty acids, since they possess a large number of duplicated genes that are annotated as encoding β-oxidation enzymes (Cole et al., 1998).

We examined four genes involved in β-oxidation, fadA4, fadB, fadE5, and fadE23, which had previously been reported to be induced in vivo (Dubnau et al., 2005) or under several stress conditions in vitro (Hampshire et al., 2004, Schnappinger et al., 2003, Wilson et al., 1999). We found that the fadB transcript decreased >10-fold by day 30, while fadE5, fadE23 and fadA4 were moderately upregulated during growth arrest (2 to 4-fold induction between day 18 and 30) (Fig. 2C and SI Table 2). This result shows that individual fad genes respond differently in vivo, perhaps reflecting specific fatty acid substrates in the infected cell.

Tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle

AcCoA derived from the catabolism of fatty acids or sugars is assimilated via the TCA cycle, which provides biosynthetic precursors and reducing equivalents for energy generation and biosynthetic reactions. In M. tuberculosis, the TCA cycle operates as a variant in which α-ketoglutarate is converted to succinate by an α-ketoglutarate decarboxylase (kgd) and succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (gabD1 and gabD2) (Tian et al., 2005). Transcript levels of key TCA cycle genes, including kgd, were down-regulated during growth arrest (up to 25-fold by day 30; Fig. 2D and SI Table 2), implying that the TCA cycle in growth-arrested bacilli functions differently than in growing cells.

Glyoxylate shunt and methylcitrate cycle

M. tuberculosis utilizes two additional pathways for assimilating AcCoA and PropCoA from fatty acid and cholesterol catabolism. One is the glyoxylate shunt, which comprises the sequential activities of isocitrate lyase (icl) and malate synthase (glcB). It converts AcCoA into C4-intermediates while bypassing the decarboxylation steps of the TCA cycle. The second pathway is the methylcitrate cycle. In this cycle PropCoA is converted to pyruvate via three specific enzymatic activities, methylcitrate synthase (prpC), methylcitrate dehydratase (prpD), and 2-methyl-isocitrate lyase (icl) (Munoz-Elias et al., 2006). In M. tuberculosis, 2-methyl-isocitrate lyase and isocitrate lyase activities are encoded by a single gene (called icl or icl1, rv0467) (Gould et al., 2006).

Transcript enumeration by qPCR showed that expression of icl was moderately induced (up to 3-fold between days 15 and 30), while glcB was down-regulated (10-fold) in growth-arrested bacilli. Levels of prpDC mRNA peaked (>10-fold) at day 21 and remained high (5-fold at day 100) (Fig. 2E and SI Table 2). Thus, three genes involved in the methylcitrate cycle (prpC, prpD and icl) are upregulated. We note that the lack of coordinated regulation of icl and glcB separates M. tuberculosis from other bacteria, including closely related Actinobacteria such as Corynebacterium glutamicum (Wendisch et al., 1997). We propose that, even though glcB is downregulated, the flux through the shunt increases because isocitrate lyase is the key enzyme in the TCA cycle/glyoxylate shunt transition (Walsh & Koshland, 1985).

Gluconeogenesis

Growth on fatty acids, TCA cycle intermediates, and other substrates that enter the TCA cycle via AcCoA requires the synthesis of glycolytic C3-intermediates, such as PEP and pyruvate, via the decarboxylation of C4-intermediates of the TCA cycle. The enzyme combinations required for C4-decarboxylation and C3-carboxylation vary among bacterial species. M. tuberculosis encodes pyruvate carboxylase (pca), which catalyzes the pyruvate to OAA reaction, the malic enzyme (mez) for the malate to pyruvate reaction, and PEP carboxykinase (pckA) for the irreversible conversion of OAA to PEP. PEP carboxykinase activity is essential for M. tuberculosis growth and persistence in mice (Marrero et al., 2010). In addition, gluconeogenesis requires dephosphorylation of fructose 1,6-bisphosphate by a 1,6-bisphosphatase (glpX) (Movahedzadeh et al., 2004). Of the above genes, only pckA was up-regulated in tubercle bacilli during mouse lung infection (up to 3-fold induction between day 18 and 50), as previously observed (Timm et al., 2003). Levels of the pca transcript were below detection, and transcript levels for mez and glpX were down-regulated (up to 10-fold at day 30, Fig. 2F and SI Table 2). The combined upregulation of pckA and downregulation of glpX, which encode enzymes catalyzing irreversible reactions, point toward C3-compound synthesis during M. tuberculosis growth arrest.

Glutamate and glutamine synthesis

To gain insight on how M. tuberculosis growth arrest affects carbon flux between carbon and nitrogen metabolism via the TCA cycle intermediate α-ketoglutarate, we probed the expression of genes involved in the metabolism of glutamate, which is one of the most abundant cellular metabolites in tubercle bacilli (Tian et al., 2005). Glutamate is synthesized by glutamate synthase (gltDB) from α-ketoglutarate and glutamine, the primary product of ammonium assimilation. Glutamine is synthesized by glutamine synthetase, which is encoded by the essential gene glnA1 (Harth et al., 2005, Tullius et al., 2003). Glutamate dehydrogenase (gdh) can also participate in glutamate metabolism by catalyzing the reversible reaction from glutamate to α-ketoglutarate and ammonium.

We found that glnA1 and gdh were down-regulated (~5-fold) by day 30 (Fig. 2G and SI Table 2). In contrast, gltDB was induced (up to 3-fold) between day 18 and 30, suggesting that M. tuberculosis directs its carbon flux from α-ketoglutarate toward formation of glutamate during growth arrest. This direction of the carbon flux is supported by the decreased expression of kdg in the TCA cycle variant (see above). Glutamate may function as a nitrogen reserve to be utilized for bacterial re-growth when environmental conditions become favorable. It may also serve as a “compatible solute” to keep metabolic enzymes functional under stress conditions (Kempf & Bremer, 1998). Moreover, glutamate contributes to mycobacterial cell wall structure (Harth et al., 2000). The observed downregulation of glutamine synthetase (glnA1) in non-growing bacilli is consistent with a reduced requirement for glutamine, which is a precursor of the cell wall component poly-L-glutamine (Tullius et al., 2003). Thus, the ratio of poly-L-glutamate to poly-L-glutamine in the M. tuberculosis cell wall is expected to increase during growth arrest.

Metabolic scheme I: Accumulation of C3 compounds

The changes in mRNA abundance reported above suggest that as tubercle bacilli stop replicating, they respond to the decreased demand for energy and biosynthetic precursors by downregulating glycolysis, PPP, and the TCA cycle. The resulting reduced synthesis of NADH from central metabolism fits well with the reduced activity of the electron transport chain postulated in our previous work (Shi et al., 2005). In the context of decreased TCA cycle activity, C4 compounds (malate and OAA) are mostly generated via the increased activity of the glyoxylate shunt, which also serves an anaplerotic function (Gottschalk, 1985). OAA is then converted to PEP by PEP carboxykinase. Carbon from PropCoA is directed toward pyruvate formation via the methylcitrate cycle. In addition to the above pathways, PEP and pyruvate are formed via the concerted up-regulation of glycolytic phosphofructokinase (pfkB) and down-regulation of gluconeogenic fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase (glpX), which would inhibit late steps of gluconeogenesis. Thus, the flux of carbon during growth arrest of M. tuberculosis is expected to be toward the generation of the C3 compounds PEP and pyruvate.

Lipid biosynthesis

To explore the metabolic fate of C3 compounds during growth arrest, we probed two aspects of lipid biosynthesis: (i) synthesis of TAG, a storage lipid implicated in the stress response and long-term survival of M. tuberculosis (Daniel et al., 2004, Garton et al., 2008, Low et al., 2009); and (ii) biosynthesis of major cell-wall components, such as mycolic acids and multimethyl-branched lipids, that utilize significant amounts of ATP, reducing power, and biosynthetic precursors generated from central metabolism.

TAG synthesis

TAGs are synthesized from glycerol 3-P and short- or intermediate-chain acyl primers. Genes involved in synthesis of monoacylglycerol 3-P (plsB2) and diacylglycerol 3-P (rv2182c and plsC) were expressed at an unchanged or slightly reduced (~2-fold) level during growth arrest (Fig. 2H and SI Table 2). Of the multiple TAG synthases encoded by M. tuberculosis, the TAG synthase encoded by tgs1 (TGS1) accounts for most of the TAG synthetic activity, at least when examined in vitro (Daniel et al., 2004, Sirakova et al., 2006). This gene, which is regulated by dosR/devR, was strongly up-regulated in growth-arrested bacilli (20 to 60-fold between day 18 and 100) (Fig. 2H and SI Table 2), suggesting that TAG accumulates in non-growing bacilli in mouse lungs, as seen with non-growing bacilli in vitro (Garton et al., 2002). Much smaller changes were seen with other TAG synthase genes: rv3371 increased and rv3734 decreased by 2–3 fold at day 30.

Mycolic acid synthesis

Mycolic acids are long-chain, high-molecular-weight α-alkyl, β-hydroxyl fatty acids that are essential components of the mycobacterial cell wall. They are synthesized by the type I and type II fatty acid synthase systems (FAS-I and FAS-II) (Bhatt et al., 2007). FAS-I, which is a single, multi-domain polypeptide encoded by fas, mediates de novo synthesis of intermediate-length, saturated α-chain of mycolic acids (C26) and synthesis of short-chain fatty-acyl-CoA primers (C16). FAS-II is a multi-enzyme complex that elongates the acyl-CoA primers generated by FAS-I to produce the full-length meromycolate chain of mycolic acids (Bhatt et al., 2007). FAS-I and FAS-II are linked by the activity of a β-ketoacyl-AcpM synthase III (fabH), which catalyzes the condensation between FAS-I acyl-CoA primers and malonyl-AcpM (the product of malonyl-CoA activation by malonyl-CoA:AcpM transacylase). The fabH gene product also funnels precursors to FAS-II (Choi et al., 2000).

We observed that fas (FAS-I system) was upregulated (up to 10-fold) between days 15 and 30 of infection. In the FAS-II system, kasA, one of the genes of the kas operon (Gupta & Singh, 2008), was modestly induced (2-fold), while expression of the unlinked fabG1 decreased ~10-fold. In addition, fabH was strongly down-regulated (25-fold) (Fig. 2I and SI Table 2). The down-regulation of fabH strongly suggests uncoupling of the FAS-I- and FAS-II-mediated reactions. The potential consequences of such uncoupling on the fate of the FAS-I product and on the structure of the cell wall of non-growing bacilli are discussed below (Metabolic scheme II).

Synthesis of multimethyl-branched lipids

Multimethyl-branched lipids, which include phthiocerol dimycocerosate (PDIM) and sulfolipids (SL), are uniquely found in the cell envelope of pathogenic mycobacteria, where they have been associated with virulence and modulation of host immune responses (Karakousis et al., 2004). These compounds are synthesized by specialized polyketide synthases that elongate straight-chain fatty acids by stepwise addition of short acyl chains (Jackson et al., 2007). Precursors for the synthesis of PDIM and SL are straight-chain fatty-acid-acyl primers and methylmalonyl-CoA (MMA), the product of PropCoA activation by a PropCoA carboxylase (Gago et al., 2006).

Expression of accD5, which encodes the PropCoA carboxylase β chain, was decreased at day 21, concurrent with bacterial growth arrest. Levels of mutAB, which encodes the MMA-succinyl-CoA mutase that catalyzes the interconversion between MMA and succinyl-CoA (Savvi et al., 2008), were below qPCR detection. Genes involved in the synthesis of PDIM were down-regulated (4- to 10-fold), while pks2, which encodes a polyketide synthase involved in the synthesis of the main sulfolipid SL-1, was moderately up-regulated (>2-fold) by day 30 (Fig. 2J and SI Table 2). These data are consistent with PDIM synthesis decreasing and, albeit modestly, SL-1 synthesis increasing as tubercle bacilli enter the non-replicative state.

Metabolic scheme II: TAG accumulation and altered cell wall composition

Based on the results reported above, we propose that the strong down-regulation (25-fold) of the fabH product, which bridges the FAS-I and FAS-II systems during mycolic acid synthesis, leads to uncoupling of the FAS-II system (elongation) from FAS-I (de novo synthesis). Consequently, the FAS-I product would be rerouted to other pathways, including TAG synthesis. Indeed, TAG, which is likely produced by de novo synthesis (Sirakova et al., 2006), accumulates in tubercle bacilli as they stop growing in response to stress in vitro, concurrent with decreased fatty acid incorporation into phospholipids and loss of acid-fastness (Deb et al., 2009).

Our data are also consistent with the possibility that the cell wall of non-growing tubercle bacilli differs structurally from that of growing bacilli. Once uncoupled from FAS-I, the FAS-II system would elongate the existing meromycolate chain of mycolic acid rather than the newly made FAS-I products. Additionally, the slight up-regulation of SL-1 synthetic genes and the concurrent down-regulation of PDIM biosynthetic genes suggest that MMA, a precursor for both PDIM and SL-1, could be rerouted from PDIM to SL-1, in agreement with biochemical data showing that blocked synthesis of PDIM leads to increased relative abundance and mass of SL-1 (Jain et al., 2007). Peptidoglycan, another cell-wall component, is also remodeled in non-replicating tubercle bacilli (Lavollay et al., 2008).

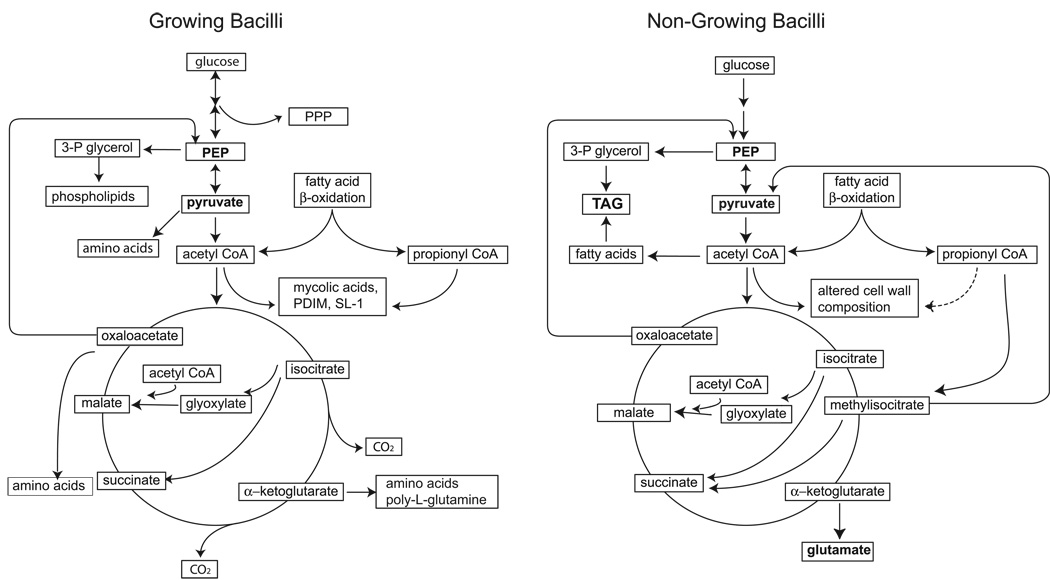

Carbon flow redistribution

Collectively, the transcription profiling data presented above lead to a model of carbon flow redistribution during growth arrest of M. tuberculosis (Fig. 3). The model predicts that, when tubercle bacilli stop replicating, the main function of central metabolism shifts from providing energy and biosynthetic precursors for bacterial growth to accumulating the storage compounds TAG and glutamate. A key functional shift occurs at the metabolic node that mediates interconversion of C4-compounds and C3-compounds, as seen in the response to stress by many microorganisms (Cortassa et al., 2000, Sauer & Eikmanns, 2005). The proposed accumulation of glutamate and TAG is another common theme of metabolic adaptation to stress (Murphy, 2001, Kempf & Bremer, 1998, Alvarez & Steinbuchel, 2002, Waltermann & Steinbuchel, 2005). These storage compounds may serve as carbon and energy sources for long-term persistence and re-growth (Low et al., 2009). Aspects of the model, such as upregulation of the glyoxylate shunt and glutamate synthesis, are supported by the results of isotopomer-assisted metabolite analysis of hypoxic adaptation in M. smegmatis (Tang et al., 2009).

Fig. 3. Metabolic model of M. tuberculosis infecting the mouse lung.

In growing bacilli, carbon from fatty acid degradation and sugars is routed via the central metabolism toward generation of energy and biosynthetic precursors required for bacterial growth. Assimilation of AcCoA and PropCoA leads to the synthesis of major cell-wall components such as mycolic acids, PDIM, and poly-L-glutamine. The glyoxylate shunt is also active, as shown by a requirement for isocitrate lyase activity throughout mouse lung infection (Munoz-Elias & McKinney, 2005). In non-growing bacilli, glycolysis, PPP and TCA cycle are downregulated. AcCoA is preferentially assimilated through the glyoxylate shunt and gluconeogenetic reactions leading to PEP, while PropCoA is preferentially assimilated via the methylcitrate cycle leading to pyruvate. The resulting formation of PEP and pyruvate, which also results from reduced de novo synthesis of sugars, leads to rerouting of carbon flow toward glyceroneogenesis and TAG synthesis. Some AcCoA is also shunted into glutamate biosynthesis. Moreover, uncoupling of FAS-I and FAS-II activities leads to rerouting of FAS-I product toward TAG synthesis and utilization of AcCoA for meromycolate elongation rather than de novo synthesis. Together, reduced PDIM synthesis, slightly increased sulfolipid-1 (SL-1) synthesis, reduced poly-L-glutamine synthesis, increased poly-L-glutamate synthesis, and meromycolate elongation result in cell-wall remodeling.

In silico metabolic model simulation of M. tuberculosis metabolic state during growth and growth arrest

The metabolic model sketched above is based on transcriptional data obtained from key genes involved in central and lipid metabolism. To begin to assess how transcriptional data correlate with metabolic reactions, we took an in silico approach utilizing metabolic networks and flux balance analysis (FBA). With this approach, simulations are performed in which input is nutritional substrate and output is the biomass composition of an in silico “cell”. Biomass is formed through reactions ordered in a metabolic network. The outcome of the simulations is the estimation of fluxes through each reaction in the metabolic network required to obtain maximal biomass. We used these methods to predict metabolic flux patterns in growing and non-growing tubercle bacilli and to assess whether the predicted fluxes were compatible with the bacterial mRNA abundance data obtained in vivo. Even though the in vivo transcriptional profiling interrogated only selected metabolic pathways, we used a genome-scale metabolic network of M. tuberculosis (GSMN-TB) [nearly 900 reactions (Beste et al., 2007)] for the simulations in silico, because regulation of metabolism is a global phenomenon rather than one that depends on particular rate-limiting steps (Fell, 1992).

We first constructed two in silico cells by adjusting biomass composition. One cell represented growing M. tuberculosis, while the other represented the more minimal cell composition predicted for non-growing M. tuberculosis (Experimental Procedures and SI Tables 3 and 4A–B). We then used FBA to predict optimal fluxes through each reaction in the network in the models for growing and non-growing cells, when glucose and phospholipid, alone and in combination were used as carbon sources. Ratios of optimal fluxes were calculated to identify metabolic flux differences between growing and non-growing bacilli. The flux solutions, which are shown in SI Table 4C–H for all (~ 100) central metabolism reactions in the GSMN-TB network, were then compared to the qPCR data.

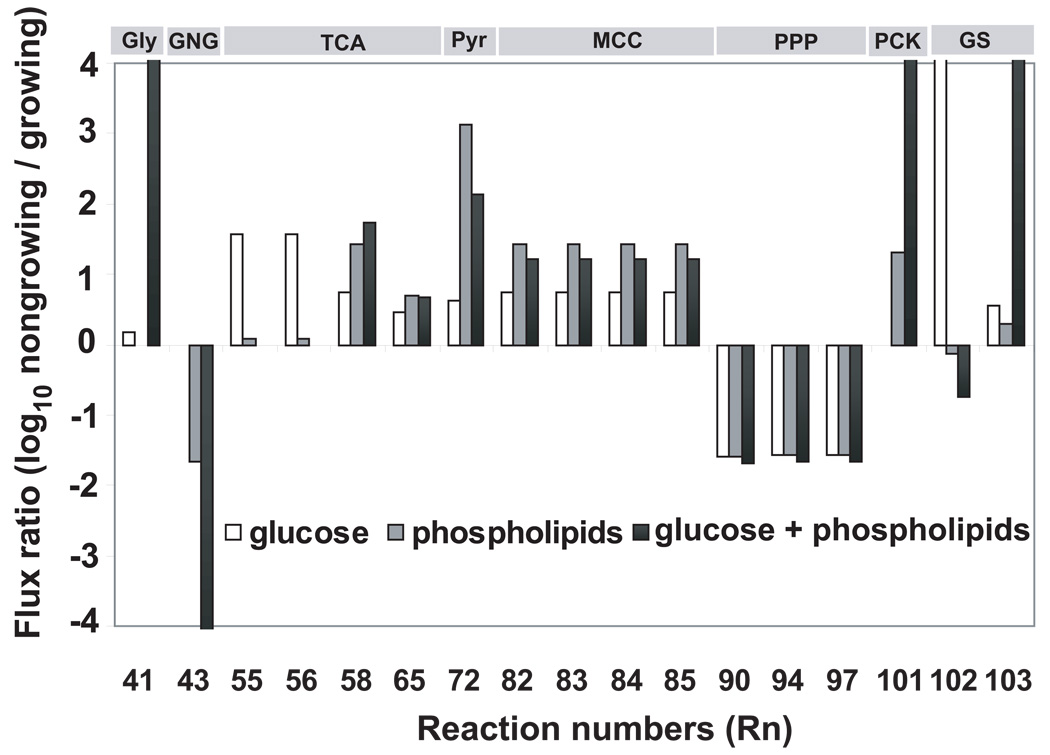

For critical pathways of central metabolism, the flux solutions associated with the comparison between growing and non-growing cells were consistent with the in vivo data (Fig. 4). First, increased flux in the glyoxylate shunt (Rn 103) and methylcitrate cycle (Rn 82–85) was predicted under all nutritional conditions. This result suggests that increased utilization of these pathways is a response to reduced growth rate rather than to carbon source changes. Second, fluxes through the PPP were predicted to decrease, as expected from the mRNA studies. Third, when glucose and phospholipid were used together as substrate, fluxes through the reactions mediated by pckA and mez (Rn 72 and Rn 101) toward C3-compound formation were predicted to increase. Fourth, the only glycolytic reaction predicted to increase was that mediated by pfkA,B (Rn 41), while the gluconeogenic reaction catalyzed by fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase (glpX) (Rn 43) was predicted to decrease. The latter two sets of results agree with the PEP and pyruvate synthesis proposed in the metabolic model in Fig. 3.

Fig. 4. Metabolic flux changes during M. tuberculosis growth arrest predicted by in silico modeling.

FBA of a genome-scale metabolic model of M. tuberculosis containing ~900 unique reactions (Beste et al., 2007) was conducted. The indicated substrates were used as input, and biomass of growing and non-growing tubercle bacilli cells was used as output (details in SI Tables 3 and 4A–B). Shown are ratios between the predicted flux values for growing and non-growing cells for 17 central metabolism reactions described in the text. Flux ratio calculations for all central metabolism reactions (~100) are shown in SI Table 4C–H. Positive ratios indicate fluxes in the same direction in growing vs. non-growing bacilli, and negative ratios indicate reactions in the opposite direction. Flux ratios that reach the +4/−4 value in the figure have values outside the range shown (see SI Table 4C–H). Reaction numbers are from the metabolic model (SI Table 4C–H). Abbreviations: Gly, glycolysis; GNG, gluconeogenesis; Pyr, pyruvate metabolism; TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle; MCC, methylcitrate cycle; PPP, pentose phosphate pathway; PCK, PEP carboxykinase; GS, glyoxylate shunt.

Differences between in vivo data and in silico predictions were also observed. In general, a lower degree of concordance was seen between experimental data and in silico fluxes when glucose and phospholipids were used separately. For example, fluxes through several TCA cycle steps (Rn 55, 56, 58, 65) were predicted to be higher in non-growing bacilli in silico (Fig. 4), but the corresponding genes were not up-regulated in vivo. Other differences involved obtaining the same metabolic outcome in silico and in vivo with different routes/reactions being utilized. For example, the mouse infection data showed up-regulation of icl (the first gene in the glyoxylate shunt), while in silico analysis revealed an increase in flux associated with the second reaction (Rn 103, mediated by malate synthase). Also, non-growing cells showed up-regulation of pckA, but not mez, in vivo, while fluxes through both reactions were predicted to increase in silico.

In conclusion, the results of the in silico simulations were consistent with the main aspects of the metabolic model derived from the qPCR data, although the same metabolic outcome was sometimes obtained via different routes in silico and in vivo. This result presumably indicates a need for introducing additional constraints in silico to fully recapitulate the in vivo state.

Adaptation of carbon metabolism of M. tuberculosis to stress in vitro

The finding that metabolic shifts accompanying growth arrest were largely independent of nutrient availability in silico led us to test experimentally whether these metabolic shifts were related to bacterial growth rate or to nutrient availability. To address this question, we compared transcription profiles associated with growth arrest of M. tuberculosis in the mouse lung with those of M. tuberculosis cultures subjected to bacteriostatic treatments in media containing different carbon sources.

Metabolic characteristics of growth-arrested bacilli in enriched culture media

We first examined whether transcript abundance changes in the metabolic genes examined in vivo were also seen when M. tuberculosis cells were cultured in standard rich media (containing glucose, fatty acids, and amino acids; see Experimental Procedures) and subjected to either of two bacteriostatic stressors, gradual O2 depletion (Wayne & Hayes, 1996) and treatment with nitric oxide (NO) released from diethylenetriamine/NO (DETA/NO) (Voskuil et al., 2003).

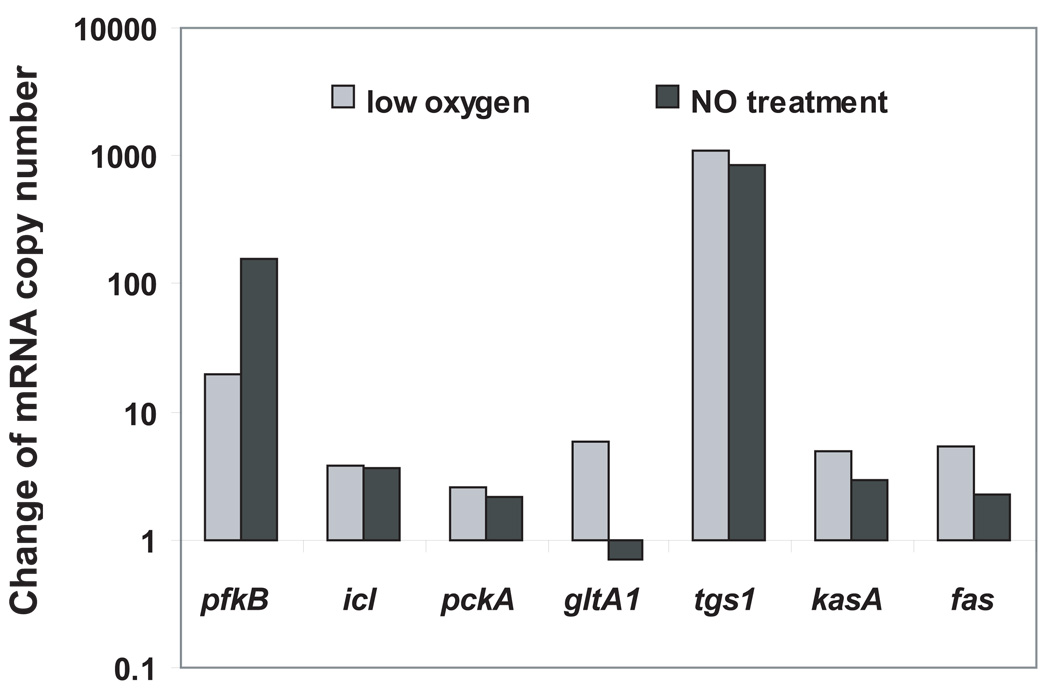

We found a significant overlap in gene expression profiles between non-growing bacilli in vivo and in vitro. Key carbon metabolic pathways/reactions up-regulated in mouse lungs were also induced in growth-arrested cultures (Fig. 5 and SI Tables 2 and 5A–B). These included glycolysis (pfkB), the glyoxylate shunt (icl), gluconeogenesis (pckA), synthesis of short- to intermediate-chain-length fatty acids (fas), elongation of meromycolate of mycolic acid (kasA), and synthesis of TAG (tgs1) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Expression changes of metabolic genes of M. tuberculosis during hypoxia and after treatment with NO in cultures grown in enriched media.

M. tuberculosis cells were cultured in standard Dubos Tween-Albumin medium, and mid-log-phase cultures were subjected to gradual O2 depletion (Wayne model) or treatment with 100µM DETA/NO. Culture aliquots were harvested at multiple times post-treatment. Transcripts were enumerated by qPCR and normalized to 16S rRNA. Shown are ratios between the means of normalized mRNA copy numbers [at hours 102 and 126 in hypoxia, or after 0.5-h of DETA/NO treatment] and the mean of the mid-log-phase culture data. The hypoxia data are from one of two independent repeats, which gave very similar results (measurements for all genes and time points tested are shown in SI Table 5A). The NO treatment data were obtained from triplicate samples [ratios for additional genes and time points tested are shown SI Table 5B; raw data (means and SD) for all genes and time points tested are shown in SI Table 5C].

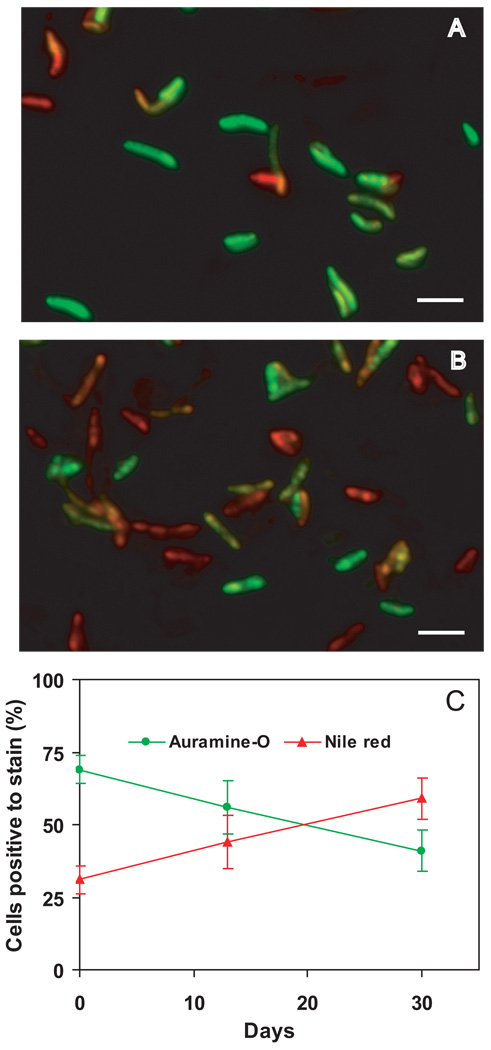

The induction of tgs1 should result in accumulation of TAG in non-growing bacilli. When we tested this possibility in the gradual O2 depletion model by cytological staining and microscopy, we found that hypoxic cultures gradually accumulated neutral lipids while losing acid fastness (Fig. 6), as previously seen with M. tuberculosis cultures subjected to multiple stress conditions (Deb et al., 2009). Accumulation of TAG provides a phenotypic correlate of tgs1 mRNA increase.

Fig. 6. Accumulation of lipid bodies and loss of acid-fastness in M. tuberculosis cells during hypoxia.

M. tuberculosis cultures were subjected to gradual O2 depletion (Wayne model). Aliquots from mid-log cultures (panel A) and cultures at day 30 of the hypoxic time course (anaerobiosis) (panel B) were stained for acid-fastness with Auramine-O (green) and for lipid body accumulation with Nile Red (red). Cells were examined by fluorescence microscopy at the same intensity for all samples with Z stacking to get the depth of the scan field. Overlaid images of Auramine-O- and Nile-Red-stained cells are shown. Bar = 4µM. Panel C: Cells stained with Auramine-O (green line) or Nile-red (red line) were counted from three microscopic fields. Means (and SD) of % stain-positive cells are shown.

Only two sets of genes showed different profiles under the three conditions (mouse, hypoxia, and NO treatment). One pertained to four fad genes, which responded differently in the three conditions, suggesting that fad gene responses are condition-specific. The other was prpCD in the methylcitrate cycle, which was induced during mouse infection and under hypoxia, but not with NO exposure (Figs 2 and 5, and SI Tables 2 and 5A–B). This result may reflect different levels of the accessory sigma factor E, which regulates the prpCD response (Manganelli et al., 2001) under several stress conditions (Datta and Gennaro, unpublished data).

The observation that the vast majority of metabolic genes probed gave the same response to three bacteriostatic conditions favors the possibility that these responses are associated with growth arrest rather than with nutrient availability (the latter presumably varies between the in vivo situation and the culture conditions utilized in vitro). This possibility was tested by utilizing fatty-acid-free culture media (below).

Metabolic characteristics of growth-arrested bacilli in media containing defined carbon sources

We next carried out transcription profiling of M. tuberculosis cultures grown in two media containing defined carbon sources but no fatty acid. One culture medium was simplified 7H9 medium in which glucose and glutamate serve as carbon and energy source. The other was LIM minimal medium in which glucose was the sole carbon and energy source (media composition is found in SI Tables 6A–B). Potential sources of fatty acids, such as bovine serum albumin (BSA) and Tween 80, were excluded (see Experimental Procedures).

When M. tuberculosis cultures grown in the above media were treated with bacteriostatic concentrations of NO, we found that key metabolic genes, such as icl, pckA and tgs1, were induced (Table 1). These data clearly establish that the upregulation of pathways, such as the glyoxylate shunt, gluconeogenesis, and TAG synthesis, are not necessarily linked with a change of substrate from sugar to fatty acids during infection, but with the change of bacterial growth rate associated with the response to stress.

Table 1.

Effects of NO on the transcript levels of selected M. tuberculosis central metabolism and lipid metabolism genes in cultures grown with defined carbon sources.

|

Parameters |

Fold change of mRNA copy number |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIM | 7H9-S | |||||

| Time | icl | PCkA | tgs1 | icl | pckA | tgs1 |

| 0.5h | 10.2 | 4.7 | 118.0 | 6.3 | 3.0 | 45.2 |

| 1h | 4.1 | 3.6 | 264.6 | 14.0 | 21.2 | 97.2 |

| 2h | 1.9 | 1.4 | 268.7 | 10.4 | 12.1 | 60.8 |

M. tuberculosis cultures were grown in modified Middlebrook 7H9 and LIM minimal medium with defined carbon sources, as described in the Experimental procedures. Mid-log culture was treated with 100 µM of DETA/NO and samples were collected at hours 0.5, 1 and 2 post-treatment. Transcripts were enumerated by qPCR as per the Fig. 2 legend. Shown are ratios of means of normalized mRNA copy numbers (from three independent experiments) at the indicated time points post-treatment relative to aerated mid-log growth. 7H9-S, simplified 7H9 medium; LIM, LIM minimal medium.

Activity of key central metabolic enzymes during growth arrest in vitro

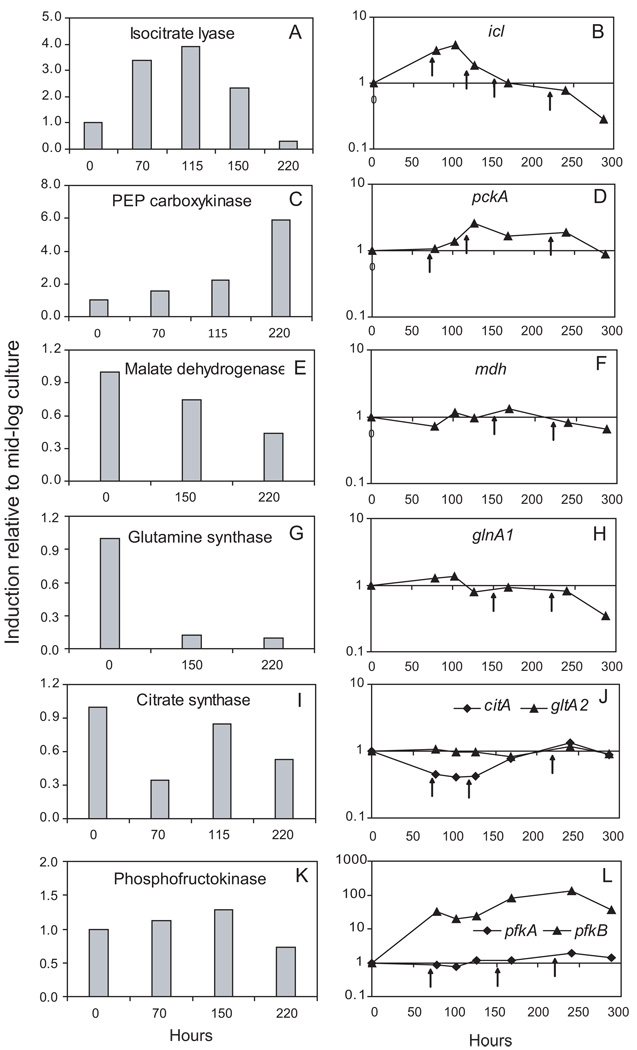

We also measured changes in enzyme activities occurring during hypoxia to determine how they correlated with expression of the corresponding genes under the same conditions. We first tested activity of three enzymes encoded by genes seen as up-regulated in the hypoxic time course. The activity of isocitrate lyase and PEP carboxykinase increased during hypoxic stress (Fig. 7A–D). The activity of methylcitrate synthase, which is encoded by prpC, was much lower than that of citrate synthase (~35–80 fold) (SI Table 7), likely reflecting the relative low level of prpC expression. We then tested activity of the products of three genes that were down-regulated during hypoxia. We found that malate dehydrogenase activity decreased during the hypoxic course (Fig. 7E–F). A decrease was also observed during hypoxic stress for glutamine synthetase activity (~10-fold), which was more pronounced than the decrease in mRNA abundance of glnA1, the major glutamine synthetase gene of M. tuberculosis (Harth et al., 2005, Tullius et al., 2003) (5-fold) (Fig. 7G–H). The pattern seen with glutamine synthetase and glnA1 was also seen with glutamate synthase activity and gltB expression. In this case, enzyme activity was low [<0.005 ± 0.001 mmoles/min/mg] during logarithmic growth and was further reduced to below detection (< 0.0001 mmoles/min/mg) during hypoxic stress (SI Table 7). Taken together, we found that the changes in enzyme activity correlated well with changes in RNA abundance with single isoform enzymes.

Fig. 7. Activity of key metabolic enzymes and corresponding mRNA profiles during hypoxia in vitro.

Mid-log cultures of M. tuberculosis were subjected to gradual O2 depletion (Wayne model). For the enzymatic assays, samples from triplicate cultures were harvested at multiple time points of the hypoxic time course corresponding to expression changes of the corresponding genes. Left panels: activity results for each enzyme, as indicated. Right panels: copy numbers of the corresponding transcripts. Data are shown as ratios between means of measurements at the indicated time point and those at time 0 (mid-log culture). Raw data (means and SD) for each time point are shown in SI Table 7.

When multiple enzyme isoforms existed or when genes encoding isoforms of the same enzyme responded differently to the hypoxic stress, comparisons between enzymatic activity and RNA abundance were more complex. We examined two such cases. In one example, the observed reduction in the activity of citrate synthase, which is expressed from citA and gltA2, tracked changes of mRNA abundance for citA, but not for gltA2 (Fig. 7I–J). In another example, we observed no significant increase in phosphofructokinase activity (which is presumably expressed from pfkA and pfkB) during hypoxic conditions, even though pfkB is strongly induced (up to ~100-fold) (Fig. 7K–L). The phosphofructokinase activity, which catalyzes the irreversible, rate-limiting step of glycolysis, is highly regulated (Doelle, 1975, Thomas et al., 1972, Kotlarz et al., 1975), and the assay conditions may not reflect critical requirements for activity of this enzyme, such as the concentration of regulatory metabolites or relative oxygen tension.

Collectively, with the exception of phosphofructokinase, the changes in enzyme activities expressed by genes critical to our metabolic model largely support the mRNA abundance data.

Conclusions

The model proposed in Fig. 3 provides an integrated view of components of the response of M. tuberculosis metabolism to stress conditions imposed by host immunity. Key aspects of the model are (i) the PEP/pyruvate-OAA node is a critical switch of carbon flow distribution, as seen in other bacterial species under stress (Sauer & Eikmanns, 2005) and (ii) carbon flow is rerouted toward formation of storage compounds, such as TAG and glutamate, as also seen in the stress response of many biological systems, as diverse as sporulating bacteria and fungi, plant seeds, and hibernating mammals (Alvarez & Steinbuchel, 2002, Murphy, 2001, Cortassa et al., 2000, Waltermann & Steinbuchel, 2005). Thus, our metabolic model characterizes mycobacterial dormancy as a variation of the broader stress-response theme developed in nature.

Our results redefine a central aspect of M. tuberculosis biology. Our finding that metabolic activities central to the model are upregulated in response to stress regardless of carbon source or stress signal contradicts the view that these activities are induced in response to change in nutrient availability from sugar to fat [for example, (Honer zu Bentrup & Russell, 2001, Timm et al., 2003)]. Thus, preferential utilization of fatty acids by tubercle bacilli explains the observed requirement for glyoxylate shunt and gluconeogenic genes, such as icl and pckA, during infection, regardless of growth rate (Munoz-Elias & McKinney, 2005, Marrero et al., 2010). Upregulation of the same (and other) metabolic pathways associated with stress-induced bacteriostasis is best interpreted in the context of cell fate decisions (transition from growth to dormancy) rather than as an adaptive response to changed nutrient availability.

A limitation of our metabolic model is that it is largely based on transcript abundance data. However, critical aspects of the model are consistent with in silico simulations. Moreover, our experiments with hypoxic cultures show high concordance between expression and activity of key central metabolism enzymes affected during stress-induced bacteriostasis in vitro, suggesting that a similar concordance exists also in vivo. Furthermore, the accumulation of TAG seen in hypoxic cultures provides a phenotypic correlate to a key prediction of the model. Further ways to test the model will include direct measurements of carbon flux distribution using 13C-labelled substrates (Eisenreich et al., 2010).

In conclusion, the metabolic model presented in the present report proposes the idea that M. tuberculosis responds to host immunity by shifting its carbon flow from biosynthesis of precursors associated with cell growth to accumulation of storage compounds during the non-replicating state as a developmental response comparable to that seen with other biological examples of dormancy.

Experimental procedures

Mouse infection

C57BL/6 mice at 8–10 weeks of age were infected with M. tuberculosis H37Rv with ≈2 × 102 bacterial colony-forming units (cfu) per mouse, as described (Shi et al., 2003). At specified times (days 12, 15, 18, 21, 30, 50 and 100), lungs from three to four mice were harvested and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent RNA extraction.

Treatment of M. tuberculosis cultures in vitro

Unless otherwise specified, M. tuberculosis H37Rv was grown at 37°C in Dubos Tween-Albumin broth (Becton Dickinson), which contains glucose, asparagine, and amino acids from a pancreatic digest of casein, and Tween-80 to prevent cell clumping. Tween-80 releases oleic acids that can also be utilized by M. tuberculosis as carbon source (Cox et al., 1978). Gradual oxygen depletion and treatment with DETA/NO were performed as described (Wayne & Hayes, 1996, Shi et al., 2005). For culturing M. tuberculosis with defined carbon sources, two additional culture media were used: a modified Middlebrook 7H9 broth with glutamic acid and glucose as carbon source (SI Table 6A), and LIM minimal medium containing glucose as sole carbon source (SI Table 6B). Sources of fatty acids were eliminated in the media by replacing the surfactant Tween-80 with the non-metabolizable Tyloxapol and by dispensing of BSA. Mid-log cultures grown in these media were treated with 100µM DETA/NO and culture aliquots were harvested at hours 0.5, 1 and 2 by centrifugation and frozen in dry-ice/ethanol for subsequent RNA extraction.

Enumeration of bacterial transcripts

RNA extraction, RT-PCR, and real-time PCR for bacterial transcript enumeration from infected mouse lungs and cultures were performed, as described (Shi et al., 2003). Briefly, total RNA extraction from lungs or cultures utilized rapid mechanical lysis of M. tuberculosis in a guanidinium thiocyanate-based buffer. Reverse transcription was performed with gene-specific primers (SI Table 8) and ThermoScript transcriptase (Invitrogen). Quantitation of M. tuberculosis mRNAs was carried out by real-time PCR using gene-specific primers, molecular beacons (SI Table 8), and AmpliTaq Gold polymerase (Applied Biosystems) in a Stratagene Mx4000 thermal cycler. Measurements of mRNA copy numbers per cell were obtained by dividing mRNA copy number by the copy number of 16S rRNA in the same sample, since 16S rRNA copy numbers closely parallel CFU determinations throughout mouse lung infection (R2 = 0.9539) (Shi et al., 2003) and in hypoxic cultures in vitro (Desjardin et al., 2001).

In silico simulation of M. tuberculosis metabolic pathways at different growth states

A GSMN-TB (Beste et al., 2007) and FBA were used to assess selected metabolic pathways for growing and non-growing bacilli in silico. GSMN-TB contains nearly 900 reactions, including the variant TCA cycle containing a-ketoglutarate decarboxylase (kgd) and succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (Tian et al., 2005). In the metabolic model, input was defined as substrate utilized; output was the generation of biomass of tubercle bacilli. Biomass of “growing cells” was defined as consisting of DNA, RNA, protein, and major components of the cell wall, as previously described (Beste et al., 2007), while biomass composition for “non-growing cells” comprised trehalose dimycolate, TAG, and polyglutamate/glutamine to reflect a shift toward the minimal cell wall composition deduced from the transcription-derived model in Fig. 3 (detailed biomass composition in SI Tables 3, 4A–B). Flux distributions were obtained for maximal biomass production at each growth state by using FBA, as previously described (Beste et al., 2007). Briefly, the FBA method uses linear algebra to calculate the flux in each metabolic reaction of the model that optimizes some ‘objective function’, in our case, the production of biomass. From the perspective of the FBA analysis, the difference between growing and non-growing cells was the different biomass composition. Therefore, FBA was used to calculate flux values that would optimize production of biomass from growing and non-growing cells. The ratio between these predicted flux values (for growing and non-growing cells) provided a predicted difference of metabolic flux in each reaction between the two states.

Fluorescent staining with Auramine-O and Nile Red

Fluorescent acid-fast staining dye Auramine-O was used in combination with lipid staining dye Nile Red (9-Diethylamino-5H-benzo-α-phenoxazine-5-one). M. tuberculosis cultures were taken at multiple time points during hypoxia and heat-killed prior to staining. About 300 µl of cell suspensions were added onto a poly-lysine-coated chambered borosilicate cover glass system and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. After removing excess cell suspension, chambers were air-dried before staining. Acid-fast staining was performed by using Mycobacteria Fluorescent stain kit (Fluka). Briefly, each chamber was filled with 0.3% fluorescent Auramine-O (in 3% phenol solution), incubated in the dark for 15 min, washed with distilled water, and treated with decolorizing solution for 2 min. After washing with distilled waster, cells were stained with Nile Red dye (10 µg/ml in ethanol), incubated in the dark for 15 min, washed with distilled water, treated with counterstain (0.1% potassium permanganate) for 3 min, washed with distilled waster, and air-dried. Each chamber was examined with 100× oil immersion lens using a fluorescent microscope AXIOVERT 200M (Zeiss). The filter sets used for visualization of cells stained with Auramine-O and Nile Red were Fluorescein (excitation wavelength 475 nm and emission wavelength 530 nm) and Texas Red (excitation wavelength 590 and emission wavelength 630 nm), respectively. Scanned images were analyzed and projected by using the OPEN LAB software (Perkin Elmer).

Preparation of cell-free extracts and enzyme assays

M. tuberculosis was grown to either mid-log phase with an approximate OD580 of 0.4 under aerobic conditions and to multiple time points of non-replicating persistence following gradual oxygen depletion in 500-ml flasks. Cultures were harvested by placing them on ice for 2 hrs and then washing them twice by centrifugation with cold 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 0.05% Tween-80. Cells were disrupted in 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) using a Mini-Bead Beater (Bio Spec Products, Bartlesville, OK) with 6 repetitions of 30-sec bursts with cooling on ice between each cycle. Extracts were clarified by centrifugation, and they were sterilized by filtration through a 0.45 µm pore SpinX filter (Corning, New York). The protein concentration was determined with Bio-Rad protein assay reagents (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif).

Isocitrate lyase

isocitrate lyase activity was measured as the amount of glyoxylphenylhydrozone produced from glyoxylate (Hoyt et al., 1991). 50 µg of cell extract protein was added to a cuvette containing 50 mM MOPS buffer (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2 and 4 mM phenylhydrazine hydrochloride. The reaction was started with the addition of trisodium isocitrate to 2 mM, and the absorbance at 324 nm monitored. A control reaction without isocitrate was subtracted as background. An extinction coefficient 1.7×104 M−1 cm−1 was used to calculate the rate of glyoxylate phenylhydrazone formation.

PEP carboxykinase

GTP-dependent PEP carboxykinase was measured with a modified protocol (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2001). 50 µg of cell extract protein was added to a reaction mix containing 200 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.2), 200 µM MnCl2, 4 mM MgCl2, 10 mM PEP, 100 mM NaHCO3, 200 µM NADH, and 3 units of malic dehydrogenase from Thermus flavus. The reaction was initiated with the addition of GDP to 2 mM and followed by measuring absorbance at 340 nm. An extinction coefficient of 6,223 M−1·cm−1 was used to calculate the rates of NADH oxidation. A control reaction without PEP was included and subtracted as background.

Malate dehydrogenase

malate dehydrogenase activity was measured by the oxidation of NADH in the presence of OAA according to published protocol with minor modifications (Tian et al., 2005). Reaction mixture contains 50 µg protein, 50 mM Hepes (pH 8.0), 0.4 mM NADH and 0.4mM OAA. A control reaction without OAA was included and subtracted as background.

Citrate synthase

the assay was carried out according to published protocols (Munoz-Elias et al., 2006). Briefly, 50 µg of cell extract protein was added to a 1 ml cuvette containing 50 mM HEPES buffer (pH 8.0), 100 µM 5,5-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenozate), and 400 µM OAA (pH 8.0). The reaction was initiated with the addition of AcCoA to 70 µM and thionitrobenzene formation was followed by measuring absorbance at 412 nm. An extinction coefficient of 13,600 M−1·cm−1 was used to calculate the rates. A control reaction without OAA was subtracted as background.

Methylcitrate synthase

the assay for methylcitrate synthase activity was the same as for citrate synthase with the exception that AcCoA was replaced with PropCoA.

Phosphofructokinase

phosphofructokinase activity measurement was based on an assay involving aldolase, triose phosphate isomerase, and glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase (Alves et al., 1997). 50 µg of cell extract protein was added to a reaction mix (pH 7.5) containing 50 mM Tris, 5mM MgCl2, 3 mM NH4Cl, 1 mM KCl, 7 mM fructose 6-P, 160 µM NADH, 1 unit of fructose bisphosphate aldolase, 5 units of 3-P isomerase and 1 unit of α-glycerol 3-P dehydrogenase. The reaction was initiated with the addition of ATP to 2.5 mM, and NADPH oxidation was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 340 nm. A control reaction without 6-P fructose was included and subtracted as background.

Glutamate synthase

the assay was carried out according to published protocols (McCarthy, 1983). 50 mg of cell extract protein was added to a reaction mix containing 50 mM HEPES buffer (pH 8.0), 5 mM glutamine, and 160 mM NADH. NADH oxidation was measured by monitoring absorbance at 340 nm. A control reaction without glutamine acid was included and subtracted as background.

Glutamine synthetase

the assay measures production of γ-glutamylhydroxamate by glutamine synthetase (Tullius et al., 2001). Components were added to a final concentration of 20 mM Imidazole (pH 7.0), 20 mM arsenate, 60 mM hydroxylamine, 1 mM MnCl2, 400 mM ADP and 50 mg of cell extract protein. The reaction was initiated with the addition of glutamate to 30 mM. At 30-min intervals a 500-ml sample was removed and added to 125 ml Stop Solution (8% wt/vol trichloroacetic acid, 3.3% wt/vol FeCl3 and 2 N HCl). The absorbance at 540 nm was measured and compared to a standard curve.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Ron LaCourse for mouse infections; Michelle Thissen for technical help with the enzyme assays; Karl Drlica, Gyanu Lamichhane, Lenny Mindich, Issar Smith, and Xilin Zhao for critical reading of this manuscript. L.S. is the recipient of a CFAR grant from New York University. C.P. is the recipient of a scholarship from the NIH Fogarty International Center. The work was supported by grants from the NIAID (R.J.N., L.S. and M.L.G.), the Medical Research Services of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (C.D.S.), the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (J.J.McF.), and the Futura Foundation (M.L.G.).

Abbreviations

- AcCoA

acetyl-CoA

- DETA/NO

diethylenetriamine/nitric oxide

- FBA

flux balance analysis

- GSMN-TB

genome-scale metabolic network of M. tuberculosis

- MMA

methylmalonyl-CoA

- OAA

oxaloacetate

- PEP

phosphoenolpyruvate

- PDIM

phthiocerol dimycocerosate

- PPP

pentose phosphate pathway

- PropCoA

propionyl-CoA

- SL

sulfolipid

- TAG

triacylglycerol

- TCA cycle

tricarboxylic acid cycle

Footnotes

Author contributions: L.S., C.D.S., R.J.N., and M.L.G. designed research; L.S., C.D.S., C.P., P.D., M.P., and J.M. performed research; L.S., J.M., C.D.S., and M.L.G. analyzed data and wrote paper.

References

- Alvarez HM, Steinbuchel A. Triacylglycerols in prokaryotic microorganisms. Applied microbiology and biotechnology. 2002;60:367–376. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1135-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves AM, Euverink GJ, Bibb MJ, Dijkhuizen L. Identification of ATP-dependent phosphofructokinase as a regulatory step in the glycolytic pathway of the actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:956–961. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.956-961.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beste DJ, Hooper T, Stewart G, Bonde B, Avignone-Rossa C, Bushell ME, Wheeler P, Klamt S, Kierzek AM, McFadden J. GSMN-TB: a web-based genome-scale network model of Mycobacterium tuberculosis metabolism. Genome biology. 2007;8:R89. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-5-r89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt A, Molle V, Besra GS, Jacobs WR, Jr, Kremer L. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis FAS-II condensing enzymes: their role in mycolic acid biosynthesis, acid-fastness, pathogenesis and in future drug development. Molecular microbiology. 2007;64:1442–1454. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishai W. Lipid lunch for persistent pathogen. Nature. 2000;406:683–685. doi: 10.1038/35021159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch H, Segal W. Biochemical differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis grown in vivo and in vitro. J Bacteriol. 1956;72:132–141. doi: 10.1128/jb.72.2.132-141.1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan PJ. Structure, function, and biogenesis of the cell wall of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2003;83:91–97. doi: 10.1016/s1472-9792(02)00089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KH, Kremer L, Besra GS, Rock CO. Identification and substrate specificity of beta -ketoacyl (acyl carrier protein) synthase III (mtFabH) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275:28201–28207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003241200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon SV, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry CE, 3rd, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail MA, Rajandream MA, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston JE, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrell BG. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins DM, Wilson T, Campbell S, Buddle BM, Wards BJ, Hotter G, De Lisle GW. Production of avirulent mutants of Mycobacterium bovis with vaccine properties by the use of illegitimate recombination and screening of stationary-phase cultures. Microbiology (Reading, England) 2002;148:3019–3027. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-10-3019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortassa S, Aon JC, Aon MA, Spencer FT. Dynamics of Metabolism and its Interactions with Gene Expression during Sporulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In: Poole RK, editor. Advance in Microbial Physiology. San Diego San Francisco New York Boston London Sydney Tokyo: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 75–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox FR, Slack CE, Cox ME, Pruden EL, Martin JR. Rapid Tween 80 hydrolysis test for mycobacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 1978;7:104–105. doi: 10.1128/jcm.7.1.104-105.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel J, Deb C, Dubey VS, Sirakova TD, Abomoelak B, Morbidoni HR, Kolattukudy PE. Induction of a novel class of diacylglycerol acyltransferases and triacylglycerol accumulation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis as it goes into a dormancy-like state in culture. Journal of bacteriology. 2004;186:5017–5030. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.15.5017-5030.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb C, Lee CM, Dubey VS, Daniel J, Abomoelak B, Sirakova TD, Pawar S, Rogers L, Kolattukudy PE. A novel in vitro multiple-stress dormancy model for Mycobacterium tuberculosis generates a lipid-loaded, drug-tolerant, dormant pathogen. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6077. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjardin LE, Hayes LG, Sohaskey CD, Wayne LG, Eisenach KD. Microaerophilic induction of the alpha-crystallin chaperone protein homologue (hspX) mRNA of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Journal of bacteriology. 2001;183:5311–5316. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.18.5311-5316.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doelle HW. ATP-sensitive and ATP-insensitive phosphofructokinase in Escherichia coli K-12. European journal of biochemistry / FEBS. 1975;50:335–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb09808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubnau E, Chan J, Mohan VP, Smith I. responses of mycobacterium tuberculosis to growth in the mouse lung. Infection and immunity. 2005;73:3754–3757. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3754-3757.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenreich W, Dandekar T, Heesemann J, Goebel W. Carbon metabolism of intracellular bacterial pathogens and possible links to virulence. Nature reviews. 2010;8:401–412. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fell DA. Metabolic control analysis: a survey of its theoretical and experimental development. Biochem J. 1992;286(Pt 2):313–330. doi: 10.1042/bj2860313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gago G, Kurth D, Diacovich L, Tsai SC, Gramajo H. Biochemical and structural characterization of an essential acyl coenzyme A carboxylase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Journal of bacteriology. 2006;188:477–486. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.2.477-486.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garton NJ, Christensen H, Minnikin DE, Adegbola RA, Barer MR. Intracellular lipophilic inclusions of mycobacteria in vitro and in sputum. Microbiology (Reading, England) 2002;148:2951–2958. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-10-2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garton NJ, Waddell SJ, Sherratt AL, Lee SM, Smith RJ, Senner C, Hinds J, Rajakumar K, Adegbola RA, Besra GS, Butcher PD, Barer MR. Cytological and transcript analyses reveal fat and lazy persister-like bacilli in tuberculous sputum. PLoS medicine. 2008;5:e75. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk G. Bacterial Metabolism (Second Edition) New York: Springer-Verlag; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gould TA, van de Langemheen H, Munoz-Elias EJ, McKinney JD, Sacchettini JC. Dual role of isocitrate lyase 1 in the glyoxylate and methylcitrate cycles in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Molecular microbiology. 2006;61:940–947. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N, Singh BN. Deciphering kas operon locus in Mycobacterium aurum and genesis of a recombinant strain for rational-based drug screening. J Appl Microbiol. 2008;105:1703–1710. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampshire T, Soneji S, Bacon J, James BW, Hinds J, Laing K, Stabler RA, Marsh PD, Butcher PD. Stationary phase gene expression of Mycobacterium tuberculosis following a progressive nutrient depletion: a model for persistent organisms? Tuberculosis (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2004;84:228–238. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harth G, Maslesa-Galic S, Tullius MV, Horwitz MA. All four Mycobacterium tuberculosis glnA genes encode glutamine synthetase activities but only GlnA1 is abundantly expressed and essential for bacterial homeostasis. Molecular microbiology. 2005;58:1157–1172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harth G, Zamecnik PC, Tang JY, Tabatadze D, Horwitz MA. Treatment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with antisense oligonucleotides to glutamine synthetase mRNA inhibits glutamine synthetase activity, formation of the poly-L-glutamate/glutamine cell wall structure, and bacterial replication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:418–423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honer zu Bentrup K, Russell DG. Mycobacterial persistence: adaptation to a changing environment. Trends in microbiology. 2001;9:597–605. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt JC, Johnson KE, Reeves HC. Purification and characterization of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus isocitrate lyase. Journal of bacteriology. 1991;173:6844–6848. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.21.6844-6848.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M, Stadthagen G, Gicquel B. Long-chain multiple methyl-branched fatty acid-containing lipids of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: biosynthesis, transport, regulation and biological activities. Tuberculosis (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2007;87:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain M, Petzold CJ, Schelle MW, Leavell MD, Mougous JD, Bertozzi CR, Leary JA, Cox JS. Lipidomics reveals control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence lipids via metabolic coupling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:5133–5138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610634104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayanthi Bai N, Ramachandra Pai M, Suryanarayana Murthy P, Venkitasubramanian TA. Pathways of carbohydrate metabolism in mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv1. Canadian journal of microbiology. 1975;21:1688–1691. doi: 10.1139/m75-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakousis PC, Bishai WR, Dorman SE. Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell envelope lipids and the host immune response. Cellular microbiology. 2004;6:105–116. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempf B, Bremer E. Uptake and synthesis of compatible solutes as microbial stress responses to high-osmolality environments. Archives of microbiology. 1998;170:319–330. doi: 10.1007/s002030050649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotlarz D, Garreau H, Buc H. Regulation of the amount and of the activity of phosphofructokinases and pyruvate kinases in Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;381:257–268. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(75)90232-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavollay M, Arthur M, Fourgeaud M, Dubost L, Marie A, Veziris N, Blanot D, Gutmann L, Mainardi JL. The peptidoglycan of stationary-phase Mycobacterium tuberculosis predominantly contains cross-links generated by L,D-transpeptidation. Journal of bacteriology. 2008;190:4360–4366. doi: 10.1128/JB.00239-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Yu J, Russell DG. pckA-deficient Mycobacterium bovis BCG shows attenuated virulence in mice and in macrophages. Microbiology (Reading, England) 2003;149:1829–1835. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26234-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low KL, Srinivasa Rao PS, Shui G, Bendt AK, Pethe K, Dick T, Wenk MR. Triacylglycerol Utilization Is Required for the Re-Growth of in Vitro Hypoxic Non-Replicating Mycobacterium Bovis Bacillus Calmette-Guerin. Journal of bacteriology. 2009 doi: 10.1128/JB.00530-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manganelli R, Voskuil MI, Schoolnik GK, Smith I. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis ECF sigma factor sigmaE: role in global gene expression and survival in macrophages. Molecular microbiology. 2001;41:423–437. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrero J, Rhee KY, Schnappinger D, Pethe K, Ehrt S. Gluconeogenic carbon flow of tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates is critical for Mycobacterium tuberculosis to establish and maintain infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:9819–9824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000715107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy CM. Continuous culture of Mycobacterium avium limited for ammonia. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;127:193–197. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.127.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney JD, Honer zu Bentrup K, Munoz-Elias EJ, Miczak A, Chen B, Chan WT, Swenson D, Sacchettini JC, Jacobs WR, Jr, Russell DG. Persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in macrophages and mice requires the glyoxylate shunt enzyme isocitrate lyase. Nature. 2000;406:735–738. doi: 10.1038/35021074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Movahedzadeh F, Rison SC, Wheeler PR, Kendall SL, Larson TJ, Stoker NG. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv1099c gene encodes a GlpX-like class II fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase. Microbiology (Reading, England) 2004;150:3499–3505. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay B, Concar EM, Wolfe RS. A GTP-dependent vertebrate-type phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase from Mycobacterium smegmatis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:16137–16145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008960200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Elias EJ, McKinney JD. Mycobacterium tuberculosis isocitrate lyases 1 and 2 are jointly required for in vivo growth and virulence. Nature medicine. 2005;11:638–644. doi: 10.1038/nm1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Elias EJ, Upton AM, Cherian J, McKinney JD. Role of the methylcitrate cycle in Mycobacterium tuberculosis metabolism, intracellular growth, and virulence. Molecular microbiology. 2006;60:1109–1122. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DJ. The biogenesis and functions of lipid bodies in animals, plants and microorganisms. Prog Lipid Res. 2001:325–438. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(01)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DG, Cardona PJ, Kim MJ, Allain S, Altare F. Foamy macrophages and the progression of the human tuberculosis granuloma. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:943–948. doi: 10.1038/ni.1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassetti CM, Rubin EJ. Genetic requirements for mycobacterial survival during infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:12989–12994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2134250100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer U, Eikmanns BJ. The PEP-pyruvate-oxaloacetate node as the switch point for carbon flux distribution in bacteria. FEMS microbiology reviews. 2005;29:765–794. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savvi S, Warner DF, Kana BD, McKinney JD, Mizrahi V, Dawes SS. Functional characterization of a vitamin B12-dependent methylmalonyl pathway in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: implications for propionate metabolism during growth on fatty acids. Journal of bacteriology. 2008;190:3886–3895. doi: 10.1128/JB.01767-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnappinger D, Ehrt S, Voskuil MI, Liu Y, Mangan JA, Monahan IM, Dolganov G, Efron B, Butcher PD, Nathan C, Schoolnik GK. Transcriptional Adaptation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis within Macrophages: Insights into the Phagosomal Environment. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2003;198:693–704. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Jung YJ, Tyagi S, Gennaro ML, North RJ. Expression of Th1-mediated immunity in mouse lungs induces a Mycobacterium tuberculosis transcription pattern characteristic of nonreplicating persistence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:241–246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0136863100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Sohaskey CD, Kana BD, Dawes S, North RJ, Mizrahi V, Gennaro ML. Changes in energy metabolism of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mouse lung and under in vitro conditions affecting aerobic respiration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:15629–15634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507850102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirakova TD, Dubey VS, Deb C, Daniel J, Korotkova TA, Abomoelak B, Kolattukudy PE. Identification of a diacylglycerol acyltransferase gene involved in accumulation of triacylglycerol in Mycobacterium tuberculosis under stress. Microbiology (Reading, England) 2006;152:2717–2725. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28993-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YJ, Shui W, Myers S, Feng X, Bertozzi C, Keasling JD. Central metabolism in Mycobacterium smegmatis during the transition from O2-rich to O2-poor conditions as studied by isotopomer-assisted metabolite analysis. Biotechnol Lett. 2009;31:1233–1240. doi: 10.1007/s10529-009-9991-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AD, Doelle HW, Westwood AW, Gordon GL. Effect of oxygen on several enzymes involved in the aerobic and anaerobic utilization of glucose in Escherichia coli. Journal of bacteriology. 1972;112:1099–1105. doi: 10.1128/jb.112.3.1099-1105.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J, Bryk R, Itoh M, Suematsu M, Nathan C. Variant tricarboxylic acid cycle in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: identification of alpha-ketoglutarate decarboxylase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:10670–10675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501605102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timm J, Post FA, Bekker LG, Walther GB, Wainwright HC, Manganelli R, Chan WT, Tsenova L, Gold B, Smith I, Kaplan G, McKinney JD. Differential expression of iron-, carbon-, and oxygen-responsive mycobacterial genes in the lungs of chronically infected mice and tuberculosis patients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:14321–14326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2436197100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]