Abstract

Regioselective ring opening of N-hydroxycarbamate-derived nitroso cycloadducts by a copper-catalyzed allylic alkylation reaction was achieved and applied to the synthesis of a set of substituted diaryl ether containing compounds. Use of protected 3-hydroxybenzyl bromide allowed access to a late stage phenol intermediate after protection of the N-hydroxy moiety that was generated from the ring opening reaction. The diaryl ethers were then formed by copper-mediated coupling with arylboronic acids. After selective deprotection, alumina-promoted transcarbamoylation provided the target compounds. Previous results indicate the compounds may possess significant inhibitory potency against the proinflammatory enzyme 5-lipoxygenase.

Keywords: Regioselective Ring-opening, HeteroDiels-Alder, Bisaryl ether, transcarbamoylation, lipoxygenase

Hydroxamic acids, hydroxamates, N-hydroxycarbamates, and N-hydroxyureas are important pharmacophores due to their ability to bind biologically relevant metals such as iron and zinc.1 Previously our lab described Grignard-mediated ring opening reactions of N-hydroxycarbamate-derived nitroso cycloadducts that led to the synthesis of an N-hydroxycarbamate (ND-6008) with potent inhibitory activity against the iron-containing enzyme 5-lipoxygenase.2 5-Lipoxygenase, an important mediator of inflammation,3 has been the focus of numerous drug discovery programs for the treatment of diseases ranging from asthma to cancer.4

We sought to expand upon this result through the development of a divergent synthetic route that would allow the facile syntheses of structurally and electronically diverse analogs. We recently reported synthetic variations of the metal binding groups and found that representative compounds potently inhibit 5-lipoxygenase translocation.5 Herein, report on synthetic elaboration of analogs containing substituents on the distal ring of the diaryl ether.

Initial studies by our group demonstrated that, while acylnitroso and N-hydroxycarbamate-derived nitroso cycloadducts could be opened by Grignard reagents, the presence of catalytic copper was essential for high conversion.6 These results were later expanded upon and the overall yields were improved significantly, although regioselectivity was not achieved. In order to begin exploring the chemical space around the initial 5-lipoxygenase inhibito, conditions were required that would lead to high γ-regioselectivity (SN2′ attack), and thus, provide the material required to synthesize the desired analogs. Conditions were explored in accordance with the findings of Bäckvall et al and the postulate that SN2′ attack is favored when reaction conditions promote the formation of the monoalkyl cuprate while suppressing formation of the dialkyl, or Gilman, cuprate.7

The CuCN-catalyzed reaction of methyl and t-butyl N-hydroxycarbamate derived cycloadducts 1 with benzyl magnesium chloride was studied with respect to catalyst loading, addition time of the Grignard reagent and temperature (Table 1). When the Grignard reagent was added to the cycloadduct and CuCN (0.1 equiv) over 45 min in Et2O at room temperature (entry 1) the product arising from γ-attack was produced in 31% yield, in line with previous results. Increasing the addition time of the Grignard reagent to 3 h (entry 2) led to a modest increase in yield. Increasing the catalyst loading to 0.2 equivalents with a 3 h addition time resulted in a slight increase in yield, while 0.5 equivalents of CuCN led to the desired 1,2-product in 73% yield (entries 3 & 4).8

Table 1.

Regioselective addition of Benzyl Grignard to (±)-3-Aza-2-oxabicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-enes 1a,b

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R = | Time, min | mol % CuCN | Temp (°C) | Yield (%)a |

| 1 | a CH3 | 45 | 10 | 25 | 31 |

| 2 | b t-Bu | 180 | 10 | 25 | 50 |

| 3 | b t-Bu | 180 | 20 | 25 | 58 |

| 4 | b t-Bu | 180 | 50 | 25 | 73 |

| 5b | b t-Bu | 5 | 10 | −78 | 62 |

| 6 | b t-Bu | 90 | 40 | −78 | 64 |

| 7 | b t-Bu | 90 | 50 | −78 | 97 |

isolated yield after column chromatography.

reaction run in THF.

An interesting result was obtained when conditions expected to favor α-addition were employed (entry 5). Treatment of the cycloadduct and CuCN (0.1 equiv) with BnMgCl over 5 min in THF at −78 °C produced the 1,2-product (γ-attack) in 62% yield with none of the expected 1,4-product (α-attack) observed. Incorporating this finding with our previous results allowed the addition time to be accelerated in subsequent reactions (entries 6 & 7). Treatment of the cycloadduct with CuCN (0.4 equiv) in Et2O at −78 °C with BnMgCl over 90 min resulted in 64% yield of the 1,2-product, while the use of 0.5 equivalents of CuCN increased the yield to 97%. The lower reaction temperature also simplified workup and purification of the reaction by reducing the amount of by-products.

The initial results (Table 1, entries 1–5) were consistent with the findings of Bäckvall et al. Monoalkyl cuprate formation was favored by long addition time, high catalyst loading and higher temperatures and resulted in increased preference for γ-addition to allylic substrates. The observation that conditions normally suited to formation of higher order, Gilman, cuprates (fast addition and low temperature) resulted in an even greater preference for SN2′ is surprising. The reason for this remains unclear and warrants further scrutiny.

Next, synthesis of a late stage intermediate that would allow the divergent synthesis of diaryl ethers was pursued. Silyl protected 3-hydroxybenzyl bromide was prepared in 4 steps as shown in Scheme 1 with an overall yield of 84%.9 Employing bromide 4 in the optimized ring opening reaction afforded the N-hydroxycarbamate in an average yield of 50%. Protection of the N-hydroxy functionality of compound 5 was accomplished by installation of a second Boc group in quantitative yield using standard conditions.

Scheme 1.

Regioselective Opening of 1b with a Protected Phenol

Deprotection of the silyl group (Table 2) of 6 was initially performed with TBAF (entry 1), although a significant byproduct was observed. The byproduct presumably arose from transfer of the O-Boc group to the phenol, generating compound 8. The side reaction was suppressed when the deprotection was performed with CsF in MeOH to give the free phenol, 7, in quantitative yield (Table 2, entry 5).10

Table 2.

Silyl Group Cleavage

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluoride Source | Solvent | 7:8 | % Yield of 7 |

| TBAF | THF | 40 : 60 | – |

| TBAF @ pH 7 | THF | 40 : 60 | – |

| TBACl/KF | THF | 40 : 60 | – |

| CsF | THF | – | – |

| CsF | DMF | – | – |

| CsF | MeOH | – | 100 |

Although it has been known for over a century, the copper-mediated diaryl ether synthesis, or Ullman condensation reaction, employs harsh conditions.11 Several methods utilized to overcome these often limiting conditions have included sonication, use of alternative bases and ligands, and incorporation of removable activating groups.12 In 1998, the Evans lab, in conjunction with researchers at DuPont, reported on the facile copper-mediated coupling of phenols with arylboronic acids at room temperature, thereby greatly expanding the scope of the reaction.13 The coupling of phenol 7 with a variety of arylboronic acids (Scheme 2) proceeded with varying yields (Table 3). In general, higher yields were obtained with electron deficient arylboronic acids with the exception of the 4-CN analog, reaction of which resulted in formation of an intractable mixture of products. Additionally, the 3-N(CH3)2 and 3-pyridyl analogs, while apparently formed according to spectroscopic analysis of the crude reaction mixtures, decomposed rapidly upon purification.

Scheme 2.

Copper-mediated Boronic acid-phenol Coupling

Table 3.

Yields of compounds 9–11

| % Yield of |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | R = | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| a | 3-OMe | 49 | 67 | 91 |

| b | 3-Cl | 35 | 70 | 68 |

| c | 4-Cl | 46 | 62 | 65 |

| d | 3-CH3 | 25 | 95 | 56 |

| e | 4-CH3 | 37 | 98 | 61 |

| f | 3-F | 73 | 77 | 16 |

| g | 4-F | 69 | 100 | 53 |

| h | 3-CF3 | 66 | 76 | 54 |

| i | 4-CF3 | 66 | 92 | 66 |

| j | 4-OMe | 28 | 64 | dec. |

| k | 4-pyridyl | 29 | 65 | dec. |

| l | 3-pyridyl | dec. | — | — |

| m | 3-N(CH3)2 | dec. | — | — |

| n | 4-CN | complex | — | — |

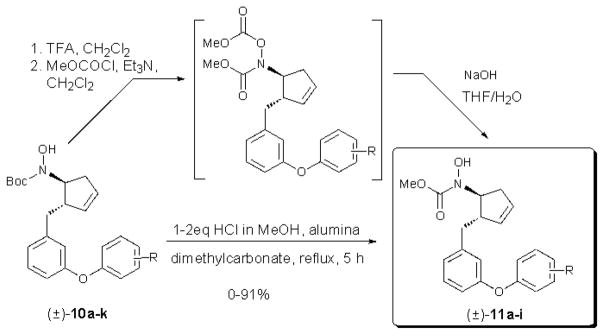

Selective removal of the carbonate protecting group was accomplished by aminolysis in methanol. Initially, the installation of the methyl N-hydroxycarbamate iron binding group was performed via acidic cleavage of the N-Boc group followed by treatment with methyl chloroformate (Scheme 3). In all cases diacylation was observed and hydrolysis was necessary to remove the undesired O-acyl group. This route was replaced by single pot alumina-mediated transcarbamoylation with methyl carbonate.14 Adaptation of a procedure for the carbamoylation of amines using green reagents accomplished the concommitant removal of the N-Boc group and installation of the methyl carbamate in acceptable yields, with exception of decomposition in the case of 4-methoxy and 4-pyridyl derivatives.15 The reaction required the addition of 1–2 equivalents of HCl, which was generated by premixing methyl chloroformate and methanol. The expected hydroxylamine intermediate was not observed during the course of the reaction.

Scheme 3.

Installation of the Iron Binding Group

In summary, optimization of a regioselective copper-catalyzed ring opening alkylation of acylnitroso cycloadducts resulted in exclusive formation of the γ-addition product in high yield and allowed the development of an efficient route to a series of diaryl ether containing compounds. The route not only employed regioselective ring opening alkylation chemistry, but also copper-mediated condensation of a phenol and arylboronic acids, as well as a useful one-pot, alumina-mediated transcarbamoylation. Based on our previous studies,5 these compounds are expected to possess significant inhibitory activity against the 5-lipoxygenase enzyme.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Bill Boggess (University of Notre Dame) and Nonka Sevova (University of Notre Dame) for mass spectroscopic analyses, and Dr. Jaroslav Zajicek (University of Notre Dame) for NMR assistance. We acknowledge the NIH (GM068012) for support of this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.(a) Ottenheim HCJ, Herscheid JDM. Chem Rev. 1986;86:697. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chimiak A, Milewska MJ. Prog Chem Org Nat Prod. 1988;53:203. [Google Scholar]; (c) Marmion C. Euro J Inorg Chem. 2004;2004:3003. [Google Scholar]; (d) Michaelides MR, Curtin ML. Cur Pharm Des. 1999;5:787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Surman MD, Mulvihill MJ, Miller MJ. J Org Chem. 2002;67:4115. doi: 10.1021/jo016275u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Samuelsson B. Science. 1983;220:568–575. doi: 10.1126/science.6301011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Brash AR. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23679–23682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.23679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Steinhilber D. Pharm Acta Helv. 1994;69:3. doi: 10.1016/0031-6865(94)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Young RN. Euro J Med Chem. 1999;34:671–685. [Google Scholar]; (b) Rubin P, Mollison KW. Prostaglandins. 2007;83:188–197. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolger JK, Tian W, Wolter WR, Cho W, Suckow MA, Miller MJ. Org Biomol Chem. 2011 doi: 10.1039/c0ob00714e. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Surman MD, Mulvihill MJ, Miller MJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:1131. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Backvall JE, Sellen M, Grant B. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:6615. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Representative Example: A flame-dried flask was charged with (±)-1b (1 g, 5.07 mmol), CuCN (227 mg, 2.54 mmol), and diethyl ether (35 mL) and cooled to −78 °C. Benzylmagnesium chloride (1.0M in Et2O, 10.14 mL, 10.14 mmol) was added over 90 min via syringe pump. After complete addition, the reaction was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for 1 h. The reaction was quenched with satd. NH4Cl (20 mL), the phases were separated, and the aqueous phase was extracted with diethyl ether (20 mL). The combined organic phases were washed with brine, dried with anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was triturated in hexanes and filtration gave (±)−2b (1.43 g, 4.94 mmol, 97%) as a white powder after recrystallization from EtOAc/hexanes. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.48 (s, 9 H) 2.39 – 2.55 (m, 1 H) 2.55 – 2.75 (m, 2 H) 2.92 (dd, J=13.48, 5.78 Hz, 1 H) 3.18 – 3.39 (m, J=10.38, 6.31, 4.28, 2.14, 2.14 Hz, 1 H) 4.46 (ddd, J=8.99, 6.85 Hz, 1 H) 5.51 – 5.73 (m, 2 H) 6.78 (br. s., 1 H) 7.22 (s, 5 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 28.58, 34.66, 40.35, 49.08, 63.59, 82.21, 126.24, 128.53, 128.84, 129.37, 133.03, 140.34, 156.95; HRMS [FAB, MH+] calcd for C17H24NO3 290.1756, found 290.1753.

- 9.Kwon S, Myers AG. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16796–16797. doi: 10.1021/ja056206n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pelter A, Hussain A, Smith G, Ward RS. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:3879–3916. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindley J. Tetrahedron. 1984;40:1433–1456. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Comdom RFP, Palacios MLD. Syn Commun. 2003;33:921. [Google Scholar]; (b) Palomo C, Oiarbide M, Lopez R, Gomez-Bengoa E. Chem Commun. 1998:2091–2092. [Google Scholar]; (c) Nicolaou KC, Boddy CNC, Li H, Koumbis AE, Hughes R, Natarajan S, Jain NF, Ramanjulu JM, Bräse S, Solomon ME. Chem Euro J. 1999;5:2602–2621. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Evans DA, Katz JL, West TR. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:2937–2940. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chan DMT, Monaco KL, Wang R, Winters MP. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:2933–2936. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vauthey I, Valot F, Gozzi C, Fache F, Lemaire M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:6347–6350. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Representative Example: A round bottomed flask fitted with a reflux condenser was charged with (±)−10a (50 mg, 0,121 mmol), alumina (50 mg), and dimethyl carbonate (2 mL). A solution of methyl chloroformate in MeOH (ca. 1M, 100 μL) was added and the reaction was immersed in a preheated oil bath at 110 °C. After 5 h, TLC (hexanes : EtOAc 3:2) showed no starting material. After cooling to room temperature the solution was diluted in CH2Cl2 and filtered through sand. The filter cake was washed with CH2Cl2 and the filtrate was concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by flash chromatography to give (±)−11a (41 mg, 0.111 mmol, 91%) as a clear, yellow oil. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.45 – 2.55 (m, J=16.55, 8.77, 2.19 Hz, 1 H) 2.58 – 2.64 (m, J=16.55, 6.98, 2.39 Hz, 1 H) 2.63 (dd, J=13.76, 8.77 Hz, 1 H) 2.81 (dd, J=13.56, 6.38 Hz, 1 H) 3.24 – 3.31 (m, J=8.54, 6.42, 4.34, 2.09 Hz, 1 H) 3.68 (s, 3 H) 3.78 (s, 3 H) 4.47 (ddd, J=8.72, 6.90 Hz, 1 H) 5.58 (dddd, J=6.13, 1.94 Hz, 1 H) 5.66 (dddd, J=6.23, 2.18 Hz, 1 H) 6.64 (ddd, J=8.32, 2.24, 1.00 Hz, 1 H) 6.85 (dd, J=7.98, 2.39 Hz, 1 H) 6.89 (t, J=1.89 Hz, 1 H) 6.95 (d, J=7.58 Hz, 1 H) 7.01 (br. s., 1 H) 7.19 – 7.27 (m, 2 H); 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 34.42, 39.85, 48.52, 53.34, 55.33, 63.33, 104.61, 108.60, 110.69, 116.77, 119.84, 124.21, 128.68, 129.44, 130.07, 132.56, 142.05, 156.72, 157.53, 158.59, 160.84; HRMS [FAB, MH+] calcd for C21H23NO5 369.1654, found 370.1649.