Synopsis

Changes in metabolic processes play a critical role in the survival or death of cells subjected to various stresses. Here, we have investigated the effects of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress on cellular metabolism. A major difficulty in studying metabolic responses to ER stress is that ER stress normally leads to apoptosis and metabolic changes observed in dying cells may be misleading. Therefore, we have used IL-3-dependent Bak−/− Bax−/− hematopoietic cells which do not die in the presence of the ER stress-inducing drug, tunicamycin. Tunicamycin-treated Bak−/−Bax−/− cells remain viable but cease growth, arresting in G1 and undergoing autophagy in the absence of apoptosis. In these cells we used NMR-based stable isotope resolved metabolomics (SIRM) to determine the metabolic effects of tunicamycin. Glucose was found to be the major carbon source for energy production and anabolic metabolism. Following tunicamycin exposure, glucose uptake and lactate production are greatly reduced. Decreased 13C labeling in several cellular metabolites suggests that mitochondrial function in cells undergoing ER stress is compromised. Consistent with this, mitochondrial membrane potential, oxygen consumption, and cellular ATP level are much lower compared with untreated cells. Importantly, the effects of tunicamycin on cellular metabolic processes may be related to a reduction of cell surface Glut-1 levels which, in turn, may reflect decreased Akt signaling. These results suggest that ER stress exerts profound effects on several central metabolic processes which may help explain cell death arising from ER stress in normal cells.

Keywords: Metabolism, ER, Autophagy, Bcl-2 proteins, Glucose, Akt

Introduction

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a vital organelle that plays an important role in the regulation of cellular homeostasis and communication (1, 2). The ER is the cellular organelle where proteins and lipids are synthesized and modified. Many protein chaperones in the ER facilitate the proper folding of individual proteins and the formation of macromolecular complexes. The disruption of ER functions by depletion of ER Ca2+ stores, inhibition of asparagine (N)-linked protein glycosylation, disturbance of disulfide bond formation, or viral infection, leads to protein misfolding and subsequent protein aggregation. The accumulation of unfolded proteins subsequently induces an ER stress response via the unfolded protein response (UPR) pathway. In mammalian cells, UPR signaling involves three pathways, IRE1 (inositol-requiring kinase-1), ATF6 (activating transcription factor 6), and PERK (RNA-dependent protein kinase-like ER kinase) (2). These sense the presence of unfolded proteins in the ER lumen and trigger various downstream signaling events. In response to different levels of UPR, there may be various types of cellular responses including apoptosis and autophagy.

While apoptosis is a tightly regulated cellular suicide program, autophagy is a cellular process for degradation of cellular components in lysosomes and is activated by a number of stressors including UPR (3–6). During autophagy, double-membrane vesicles - autophagosomes - are formed de novo to sequester cytoplasmic contents. Once the outer membranes of autophagosomes fused with lysosomal membranes, cytoplasmic contents are delivered to the lysosome lumen, where they are degraded. The resulting degradation products are released into the cytosol and may be reutilized. Autophagy is a highly regulated cellular catabolism system and deficiency in autophagy has been invoked in the pathogenesis of many human diseases, including neurodegeneration, infections, and cancer. ER stress has been reported to induce autophagy in many cellular systems and may represent a defense mechanism which promotes cell survival (7). However, more extreme ER stress can lead to autophagic cell death. Although it is not clear how pro-survival and pro-death outcomes of autophagy are regulated, it appears that the extent of autophagy may determine cell fate (8).

Cells undergoing autophagy typically exit the cell cycle and maintain a minimal metabolic rate commensurate with maintenance of cellular homeostasis and repair. A large fraction of ATP consumed is used for maintaining ion gradients across the plasma membrane and intracellular membranes, and for protein synthesis (9, 10). An important issue for cell survival is the production of sufficient metabolic energy for repair and membrane potential maintenance. How metabolic changes in ER stress-induced cellular metabolism are involved in cell fate decision is largely unknown. Here, we examined the metabolic effects of ER stress on IL3-dependent Bak−/− Bax−/− cells using a NMR-based stable isotope resolved metabolomics approach. We find that ER stress induces progressive autophagy and a relative inability to utilize extracellular glucose, resulting in reduced glycolysis and Kreb’s cycle activity. This appears to be accompanied by a reduction of Glut-1 levels on the cell surface. Together, these data suggest ER stress has marked effects on central metabolic processes, particularly glucose metabolism.

Experimental Materials and Methods

Cell lines and reagents

Bak−/−Bax−/− IL-3-dependent cells were cultured at 37°C (95/5% air/CO2) in glucose-free RPMI 1640 media (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% (v/v) dialysed Fetal Bovine Serum (Clontech, Mountain View, CA), 5 mM glucose (Sigma), 2 mM glutamine (Mediatech, Manassas, VA), 100 U/ml penicillin (Mediatech), 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Mediatech) and 3.4 ng/ml IL-3 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Wild-type murine Bax or Bak cDNA was re-expressed in IL-3-dependent Bak−/−Bax−/− cells by retroviral infection and stable clones expressing Bax or Bak were selected as described previously (11). cDNAs of Myc-tagged mouse Glut-1 or mouse Akt1 with myristolation sequence GSSKSKPKSR at its N-terminus was retrovirally expressed in Bak−/−Bax−/−IL-3-dependent cells with GFP as a marker expressed from an Internal Ribosome Entry Site (IRES) as described previously (12). Cells stably expressing Myc-tagged Glut-1 or myristolated Akt1 were obtained using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (Moflow, Dako, Carpinteria, CA). [U-13C]-glucose was purchased from Sigma Isotec (St. Louis, MO). Tunicamycin was purchased from Sigma. MitoTracker Green and MitoTracker Red were from Invitrogen. Antibodies used for western blot analysis were anti-BiP/GRP78 pAb (Assay designs, Ann Arbor, MI), anti-CHOP mAb (Santa Cruz; Santa Cruz, CA), anti-β-actin mAb (Sigma), anti-Bak pAb (Upstate; Lake Placid, NY), anti-Bax pAb (Santa Cruz), anti-LC3 pAb (Cell Signaling Technology; Danvers, MA), anti-Glut-1 pAb (Abcam; Cambridge, MA), anti-Myc mAb (Millipore; Billerica, MA), anti-Akt pAb (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Hexokinase 2 pAb (Santa Cruz), anti-p70 S6 Kinase mAb (BD Transduction Laboratories; San Diego, CA), and anti-Phospho-p70 S6 Kinase (Thr421/Ser424) mAb (Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-Phospho-Akt (Ser 473) mAb (Cell Signaling Technology).

Cell viability, cell size, and cell cycle analysis

Cell viability was measured by propidium iodide (Invitrogen) exclusion assays carried out using flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, BectonDickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) as described previously (13). Cell sizes were measured by forward scatter as described previously (14). For cell cycle analysis, 5×105 cells were sedimented (300×g for 5 minutes) and washed twice with 500 µl 1×PBS. Cells were then fixed with 1 ml 70% ethanol in 1×PBS at 4°C ovemight. After centrifugation, cells were washed twice with 1×PBS and resuspended in 500 µl 1×PBS. 50 U RNase A (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) were added to samples and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. Five µg propidium iodide was added to samples which were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C before flow cytometric analysis.

Immunofluorescence staining of myc-Glut-1

3×105 cells were sedimented (300×g for 5 minutes) and washed twice with 200 µl blocking buffer (1×PBS with 2% FBS). Cells were then resuspended with 25 µl blocking buffer containing 1.25 µl rat serum (Sigma) and 0.25 µl Fc Block (Becton Dickinson), and incubated on ice for 10 minutes. Then cells were sedimented (300×g for 5 minutes) and resuspended with 25 µl blocking buffer containing 3 µl anti-Myc antibodies (Upstate). Following 20 minute-incubation on ice, 150 µl blocking buffer was added and the cells were sedimented. After a wash with 200 µl blocking buffer, cells were resuspended with 50 µl blocking buffer containing 1 µl PE-conjugated rat anti-mouse IgG1 antibodies (BectonDickinson) and incubated on ice for 20 minutes in the dark. 150 µl blocking buffer was added to the samples followed by centrifugation. After washing with 200 µl blocking buffer, immunofluorescence was assessed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, BectonDickinson) or by fluorescence microscopy (EVOS, Advanced Microscopy Group, Mill Creek, Washington).

Electron microscopy

4×106 cells were collected in a 1.5 ml-Eppendorf tube by brief centrifugation (300×g and 5 minutes) and cell pellets were fixed with 3% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate at 4°C overnight. Prior to embedding, cells were treated with 2% osmium tetroxide followed by an increasing gradient dehydration step using ethanol and propylene oxide. Cells were then embedded in LX-112 epoxy plastic (Ladd Research, Williston, VT). Ultra-thin sections of 80 nm were cut, placed on uncoated copper grids, and stained with lead citrate and saturated aqueous uranyl acetate. Images were obtained with a Philips CM12 transmission electron microscope at 80kV as described previously (11).

Measurement of lactate, ATP, mitochondrial potential, and oxygen consumption

Lactate in the growth medium was measured using Lactate Reagent (Trinity Biotech, Co Wicklow, Ireland). In this assay, lactate is converted to pyruvate and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) by lactate oxidase. Resulting H2O2 is detected by peroxidase-catalyzed oxidative condensation of a chromogen yielding a product with maximal absorption at 540 nm. For this assay, 1 µl of sample was mixed with 100 µl Lactate Reagent in a 96-well plate. Following incubation for at least 5 minutes at 25°C, absorbance of samples at 540 nm was measured using a plate reader (Bio-tek, Winooski, VT).

For measurement of intracellular ATP levels, 0.5×106 cells were collected and resuspended in 0.5 ml 100°C water. ATP concentration in the supernatant was determined by a bioluminescence reaction using firefly luciferase and D-luciferin (Invitrogen). This assay is based on ATP-mediated light production by luciferase (emission maximum~560 nm). Briefly, 7 µl samples or standard solutions were added into 100 µl reaction solution in a 96-well plate. The readings at emission wavelength 560 nm were obtained using a luminometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

To measure mitochondrial mass and membrane potential, cells were incubated with 200 nM MitoTracker Green or MitoTracker Red at 37°C for 1 hour. The fluorescence intensity of the dye was determined by flow cytometry as suggested by the manufacturer (Invitrogen).

For oxygen consumption, 5×106 cells were collected and resuspended in 0.55 ml fresh RPMI medium. Samples were loaded into the chamber of a Strathkelvin Oxygen System (North Lanarkshire, Scotland, UK) and the loss of oxygen in the chamber was monitored.

NMR sample preparation

IL-3-dependent Bak−/−Bax−/− cells were cultured in RPMI medium containing 5 mM unlabeled glucose. 50×106 cells were collected and washed with 50 ml glucose-free 1640 RPMI medium three times, followed by resuspension in RPMI containing 5 mM [U-13C]-glucose at a final cell concentration of 0.20 × 106/ml. DMSO (control) or tunicamycin (final concentration of 3 µg/ml) were added to cells. The growth medium was collected, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C at 0, 3, 6, 9, 24, 30, and 48 hour time points. 5×106 cells were collected by centrifugation and washed 3 times with 20 ml ice-cold 1×PBS at 24 and 48 hour time points. Cell pellets were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. To extract metabolites, 200 µl growth medium sample was mixed with 200 µl 40% ice cold trichloroacetic acid (TCA) or 300 µl 10% TCA was added to cell pellets. Samples were centrifuged and lyophilized as previously described (15, 16).

NMR

NMR spectra were recorded at 14.1 T or 18.8 T on a Varian Inova spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm inverse triple resonance cold probe (cells), or at 18.8 T (media) using an inverse triple resonance probe, all at 20°C. 1D NMR spectra were recorded with an acquisition time of 2 s and a recycle time of 5 s. Concentrations of metabolites and 13C incorporation were determined by peak integration of the 1H NMR spectra referenced to the DSS methyl groups, with correction for differential relaxation, as previously described (15–18). 1H Spectra were typically processed with zero filling to 131k points, and apodized with an unshifted Gaussian and a 0.5 Hz line broadening exponential. 13C profiling was achieved using 1D 13C-edited HSQC 1H spectra recorded with a recycle time of 1.5 s, with 13C GARP decoupling centered at 80 ppm (1JCH set to 150 Hz) and during the proton acquisition time of 0.15 s.

TOCSY spectra were recorded with a mixing time of 50 ms and a B1 field strength of 8 kHz with acquisition times of 0.341 s in t2 and 0.05 s in t1. The fids were zero filled once in t2, and linear predicted and zero filled to 4096 points in t2. The data were apodized using an unshifted Gaussian and a 1 Hz line broadening exponential in both dimensions. Specific 13C isotopomers and fractional incorporation of 13C were determined by comparing the areas or volume of satellite peaks with the total integrated area or volume, with appropriate corrections for differential relaxation as previously described (15–18).

Glucose consumption was quantified by NMR using the 13C-lαH satellite signals centered at 5.22 ppm. This accounts for 36% of the total glucose. The 13C and 12C lactate and alanine concentrations were determined by integration of the methyl peak and its satellites and normalized to the concentration of the standard DSS. From this, the amount of glucose consumed, ΔGlc, and the fraction converted to lactate plus alanine, F, could be estimated, according to Eq. (1) and Eq. (2) (15–18)

| (1) |

| (2) |

1-F then represents the glucose carbon that enters other metabolites and macromolecules in the cell mass or otherwise not accounted for. Abundant media components (e.g. threonine and valine) were similarly integrated and their concentrations determined as a function of sampling time to assess the utilization of essential amino acids. The concentrations of choline metabolites (choline, phosphocholine and glycerophosphocholine) were determined from the areas of the trimethyl ammonium resonance near 3.22 ppm as described previously (15–18). NMR assignments were made according to the chemical shifts and scalar coupling patterns in TOCSY and by reference to our databases (15–18)

Results

Tunicamycin inhibits cell proliferation and induces autophagy in the absence of apoptosis

ER stress has profound effects on cellular homeostasis (2). However, the details of how ER stress might influence cellular metabolism are largely unknown. Prolonged ER stress often induces multiple forms of cell death, including apoptosis and autophagy (19). It is difficult to evaluate the effects of prolonged ER stress on cellular metabolism as membrane integrity of organelles in cells undergoing apoptosis is often disrupted, leading to the leak of cellular metabolites out of the dying cells. To avoid the perplexing variable of apoptosis, we used interleukin-3 (IL-3)-dependent Bax−/−Bak−/− hematopoietic cells as a system to evaluate the effects of prolonged ER stress on cellular metabolism. Bak and Bax double deficiency in these cells make them resistant to apoptosis induced by IL-3 withdrawal (14). Among several ER stress inducers examined in IL-3-dependent Bax−/−Bak−/− cells, tunicamycin, an inhibitor of protein N-glycosylation (20), induced dramatic ER stress and minimal cell death (Figures 1A, 1C). In the presence of 3 µg/ml tunicamycin, Bax−/−Bak−/− cells did not proliferate significantly but remained essentially 100% viable (Figures 1B, 1C). In addition, tunicamycin induced cell arrest at G1 (Figures 1D, 1E). Reexpression of Bak or Bax in Bax−/−Bak−/− cells caused cells to undergo apoptosis in the presence of tunicamycin (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 1. Tunicamycin affects proliferation, and cell cycle but not viability of IL-3-dependent cells lacking Bak and Bax.

IL-3-dependent Bak−/−Bax−/− cells were treated with either 3 µg/ml tunicamycin or DMSO (control). (A) Expression of Bip/GRP78 and CHOP was detected by western blot, ctl, control; tuni, tunicamycin. (B) Cell numbers were determined. The data represent means ± S.D. of three independent experiments. Asterisk indicates P < 0.05 (*), Student’s unpaired t test. (C) Viability of cells in the absence or presence of 3 µg/ml tunicamycin was determined by propidium iodide exclusion. Means ± S.D. of three independent experiments are shown. (D) Cell cycle profiles of cells treated with or without tunicamycin. (E) Tunicamycin induced G1 arrest. The data represent means ± S.D. of triplicate experiments.

To further characterize cells under ER stress, high-power transmission electron microscopy experiments were carried out to examine subcellular structures. Twelve hrs after tunicamycin treatment, early autophagosomes were observed in the treated cells (Figure 2A). When quantitated, the number of autophagosomes in tunicamycin-treated cells was greatly increased compared with that of the untreated cells (Figure 2B). Autophagy persisted over 48 hrs tunicamycin treatment as the cytoplasm of the treated cells was increasingly occupied with vesicular structures that contained degraded intracellular organelle remnants and exhibited characteristics of lysosomes (Figure 2A). The sizes of the treated cells were also noticeably smaller in comparison with those of the untreated cells (Figure 2C), indicating that cells underwent atrophy. Furthermore, expression of microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain (LC3) upon tunicamycin treatment was examined (Figure 2D). The conversion of LC3-I form to LC3-II form, a hallmark of autophagy, was observed in tunicamycin-treated cells, providing more evidence that tunicamycin induced autophagy in the absence of apoptosis (Figure 2E). The observation of autophagy in tunicamycin-treated Bax−/−Bak−/− cells is consistent with previously reported autophagy induced by ER stress in many other cell types (3, 6, 7).

Figure 2. Tunicamycin induces autophagy in Bak−/−Bax−/− cells.

(A) Representative electron microscopic images of IL-3-dependent Bak−/−Bax−/− cells in the absence (a, d, g) or the presence of 3 µg/ml tunicamycin for 12 hours (b, e, h) or 48 hours (c, f, i). The magnification of electron microscopy is indicated on the right. Arrows depict representative autophagosomes (h) or autophagolysosomes (i) containing recognizable cellular contents, which are quantitated in (B). Scale bar, 1 µm. (B) Quantification of the number autophagosomes per cross-sectioned cells cultured in the absence or presence of 3 µg/ml tunicamycin. Means ± S.D. of 40 randomly selected cross-sectioned cells are shown. Asterisks indicate P < 0.001 (***), Student’s unpaired t test. (C) The sizes of cells without or with the treatment of tunicamycin were determined by flow cytometry. The data represent means ± S.D. of three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate P < 0.05 (*), Student’s paired t test. (D) The effects of tunicamyicn treatment on expression pattern of LC3 were determined by western blot. Ctl, control; tuni, tunicamycin. (E) Tunicamycin induced conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II. The intensities of LC3-I and LC3-II shown in (D) were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH). Means ± S.D. of three independent experiments are shown. Asterisks indicate P < 0.05 (*), Student’s paired t test.

Tunicamycin inhibits glucose uptake and glycolysis

To understand how tunicamycin might affect cellular metabolism, we first used high resolution NMR to measure changes in the concentrations of metabolites in the growth medium. The concentrations of essential amino acids such as threonine remained almost the same, and the concentrations of unlabeled lactate in the medium were largely unchanged over 48 hrs of tunicamycin treatment (Figure 3 A). In contrast, the consumption of 13C glucose from the medium was considerably higher in the control cells than that in the treated cells (Figure 3B). Furthermore, the production of 13C lactate from glucose via glycolysis accounted for more than 50% of the glucose carbon in the control cells at 24 hrs, but was less than 35% in the treated cells (Figure 3C). Interestingly, consumption of glutamine from the medium was increased in tunicamycin-treated cells (Figure 3D). Using an enzymatic assay, it was confirmed that the total amount of lactate in the medium was reduced at least 2-fold in the presence of tunicamycin (Figure 3E). Hence, glycolytic flux to lactate was considerably attenuated in the presence of tunicamycin.

Figure 3. Tunicamycin reduces glucose consumption and glycolysis.

IL-3-dependent Bak−/−Bax−/−cells were grown in the medium containing 13C-glucose in the presence or absence of 3 µg/ml tunicamycin. The concentrations of metabolites in the medium were determined by SIRM. (A) There was no consumption of the essential amino acid threonine and no significant sources for lactate production other than 13C-glucose in IL-3-dependent cells upon 48-hour tunicamycin treatment. Lines are linear regression fits. (B) Consumption of 13C-glucose in the medium was decreased in tunicamycin-treated cells. Lines are linear regression fits. The upward curve is fitted to a quadratic function. (C) The fraction of consumed glucose that was converted to secreted lactate was decreased in the presence of tunicamycin. (D) Tunicamycin treatment promoted glutamine consumption from the medium. (E) Lactate production was reduced in tunicamycin-treated cells. The data represent means ± S.D. of three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate P < 0.05 (*), Student’s unpaired t test.

Tunicamycin reduces oxidative metabolism

In addition to glucose utilization and lactic production, we also examined the effects of tunicamycin on oxidative metabolism. The relative concentrations of critical intracellular metabolites that reflect glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway, the Krebs cycle, and pyrimidine biosynthesis were determined. As we monitored the incorporation of 13C atoms derived from 13C glucose into metabolites, these events represent de novo biosynthesis of metabolites (Supplementary Figure 1). In 1D HSQC experiments, only protons attached to 13C were observed (Figure 4A). As the natural abundance of 13C is only 1.1%, the peaks detected in this experiment largely reflect de novo biosynthesis of compounds that utilize glucose carbon. The concentrations of newly synthesized metabolites were generally higher in the control cells than those in the treated cells, consistent with the decreased glucose consumption in the presence of tunicamycin (Figure 3B).

Figure 4. Major 13C -labeled soluble metabolites in cells in the absence or presence of tunicamycin were detected by SIRM.

(A) 1D 1H-13C HSQC spectra of IL-3-dependent Bak−/−Bax−/− cells grown without (control) or with tunicamycin. There were relatively lower levels of 13C -labeling of intracellular metabolites in the presence of tunicamycin. (B) 13C-labeling of amino acids and lactate in cells was revealed by TOCSY. The box a shows the 13C satellite peaks of alanine, which surrounds the central peak that represents unlabeled alanine. Similarly, the box b shows satellite peaks of lactate C-2 and C-3. The box c shows the satellite peaks of the C-2H and C-4H resonances of glutamate and the glutamate moiety of reduced glutathione, and the box d shows the satellite peaks of aspartate C-2 and C-3. (C) Nucleotide labeling in cells in the absence (control) or presence of tunicamycin was revealed by TOCSY. Boxes a and b show the 13C satellite peaks of the ribose moieties of UTP and ATP, respectively. These species are a consequence of pentose phosphate activity. The box c and cross correspond to the C-5, 6 positions of uracil in UTP+UDP, and shows doubly labeled uracil as well as the two singly labeled species derived directly from aspartate.

More details of de novo biosynthesis of cellular metabolites were revealed by the TOCSY experiments (Figures 4B, 4C). The 13C labeling patterns in the metabolite markers of glycolysis and the Krebs cycle, including lactate, alanine, glutamate and aspartate, were determined (Figure 4B). Both alanine and lactate exhibited the characteristic square pattern of 13C satellites surrounding a central resonance that represents unlabeled compound, indicating alanine and lactate were synthesized directly from glucose (via glycolysis) with no significant metabolic scrambling (15–18). In contrast, both glutamate and aspartate resonances showed a more complex pattern of satellites, corresponding to unlabeled species, molecules that contain 13C at both positions (e.g. C2, C3 in aspartate), as well as two additional species. For aspartate, the additional species correspond to 13C212C3 and 12C213C3. The latter pattern arises from Krebs cycle activity in which doubly labeled acetyl CoA from uniformly labeled pyruvate condense with unlabeled oxaloacetate, producing first 2-oxoglutarate (2-OG) labeled at C4, C5 followed by further transformation to oxaloacetate via the Krebs cycle (Supplementary Figure 1). Because of the scrambling at the succinate step, the oxalate comprises a 50:50 mixture of 13C113C2 + 13C313C4, which is converted into aspartate by transamination. In a single turn of the Krebs cycle, this would give rise to a different satellite pattern from what was observed. Only with a second addition of labeled aetyl CoA, does the multiply labeled aspartate appear, in which both C2 and C3 are labeled in the same molecule. Similar remarks apply to the glutamate labeling pattern, as glutamate is synthesized by transamination of 2-OG (Supplementary Figure 2).

Hence, the Krebs cycle is fully operative in IL-3-dependent Bak−/−Bax−/−cells. The relative abundance of the various isotopomers was quantified as described previously (15–18). As shown in Table 1, there was a substantial decrease in the amount of multiply labeled glutamate and aspartate in the tunicamycin-treated cells, consistent with the decreased glucose uptake and flow through glycolysis. As aspartate is a direct precursor of pyrimidine ring biosynthesis, the uracil in UTP exhibits the same labeling pattern as the aspartate (Supplementary Figure 2). Shown in the TOCSY spectra of the free nucleotide pools of the cells (Figure 4C), the degree of labeling of uracil rings in the control cells was substantially higher than in the treated cells (Table 1). As the orotate dehydrogenase step occurs in mitochondria, this provides further evidence that functional respiration and Krebs cycle activity in the mitochondria of Bak−/−Bax−/− cells was compromised by tunicamycin treatment. Interestingly, significant ribose biosynthesis (pentose phosphate pathway) was observed in tunicamyicn-treated cells, albeit at a slightly reduced rate compared with that in the control cells (Table 1). Nevertheless, even at 48 hour time point, tunicamycin-treated cells were still turning over RNA, necessitating replacement by de novo nucleotide biosynthesis.

Table 1. Anabolic activities of mitochondria in cells treated with tunicamycin are compromised.

The indicated metabolites in cells treated with DMSO (control) or tunicamycin for 48 hours were calculated by integration, with correction for saturation where necessary. 13C enrichment was quantified using the peak satellites as revealed by TOCSY (Figure 4) 13C labeling in cellular glutamate, aspartate and the uracil rings of UTP was decreased upon tunicamycin treatment.

| Molecule | Site | %C (control) |

%C (tunicamycin) |

ratio (tunicamycin /control) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glutamate | 12C212C4 | 53 | 66 | 1.25 |

| 12C213C4 | 19 | 18 | 0.95 | |

| 13C212C4 | 4 | 11 | 2.75 | |

| 13C213C4 | 24 | 5 | 0.21 | |

| Aspartate | 12C212C3 | 44 | 60 | 1.36 |

| 12C213C3 | 14 | 13 | 0.93 | |

| 13C212C3 | 20 | 18 | 0.90 | |

| 13C213C3 | 22.5 | 9 | 0.40 | |

| Lactate | 12C212C3 | 46 | 40 | 0.87 |

| 13C213C3 | 54 | 60 | 1.11 | |

| Alanine | 12C212C3 | 22 | 48 | 2.18 |

| 13C213C3 | 78 | 52 | 0.67 | |

| Uracil in UTP | 12C612C5 | 63 | 83 | 1.32 |

| 13C612C5 | 12 | 5.5 | 0.46 | |

| 12C613C5 | 14 | 8.3 | 0.59 | |

| 13C613C5 | 11 | 3.4 | 0.31 | |

| UTP ribose | 12C112C2 | 3.5 | 20 | 5.71 |

| 13C113C2 | 96.5 | 80 | 0.83 |

The results presented so far demonstrate that tunicamycin induces autophagy, with a concomitant decrease in demand for glycolysis and Krebs cycle activity. This should lead to a decreased demand for ATP synthesis. To corroborate this, we measured the mitochondrial membrane potential in response to tunicamycin using mitochondrion-selective dyes. As shown in Figures 5A and 5B, tunicamycin treatment reduced the fluorescent staining of both mitochondrial potential-independent MitoTracker Green and mitochondrial potential-sensitive MitoTracker Red, indicating that both mitochondrial mass and mitochondrial membrane potential were decreased in tunicamycin-treated cells, consistent with the catabolism of intracellular organelles in cells undergoing autophagy. We also measured cellular respiration rate as well as the steady state levels of ATP in response to tunicamycin. The respiration rate decreased more than 3-fold in the presence of tunicamycin (Figures 5C, 5D), with a concomitant 2-fold decrease in the steady state ATP level (Figure 5E), consistent with decreased oxidative phosphorylation.

Figure 5. Tunicamycin reduces metabolic activities of mitochondria.

(A) The effects of tunicamycin on mitochondrial mass and membrane potential were determined by mitochondrion-selective fluorescence probes MitoTracker Green and MitoTracker Red 48 hours after the treatment of tunicamycin. (B) Tunicamycin reduced mitochondrial mass and membrane potential. Means ± S.D. of three independent experiments are shown. Asterisks indicate P < 0.05 (*), Student’s unpaired t test. (C) Oxygen consumption of 5×106 IL-3-dependent Bak−/−Bax−/− cells treated with DMSO (control) or tunicamycin at the indicated time points were measured using an oxygen meter. (D) Tunicamycin reduced mitochondrial oxygen consumption. The rate of oxygen consumption of cells under the conditions shown in (C) was measured. The data represent means ± S.D of three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate P < 0.01 (**), Student’s unpaired t test. (E) Intracellular ATP levels were reduced in tunicamycin-treated cells. Intracellular ATP levels of the indicated cells were measured. Means ± S.D. of three independent experiments are shown. Asterisks indicate P < 0.05 (*), Student’s unpaired t test.

Glut-1 levels on cell surface are reduced in tunicamycin-treated cells

Glucose uptake is partially controlled by the surface expression of glucose transporters (21, 22), and the ubiquitously expressed glucose transporter, Glut-1, is primarily responsible for glucose uptake in hematopoietic cell lines (23, 24). To explore the molecular mechanism of the reduced glucose uptake in tunicamycin-treated IL-3-dependent cells, the effect of tunicamycin on Glut-1 expression was examined. As shown in Figures 6A and 6B, tunicamycin did not significantly affect either total Glut-1 or hexokinase-2 protein expression levels. Although tunicamycin inhibits glycosylation and Glut-1 is a highly glycosylated protein, tunicamycin did not seem to alter glycosylation patterns of Glut-1. As Glut-1 transportation to cell surface is critical to its function, we examined cell surface expression levels of Glut-1 by immunofluorescence staining approach. Due to the limitations in commercially available Glut-1 antibodies, we failed to detect endogenous Glut-1 expression on cell surface. As previous studies show that trafficking of exogenously expressed Glut-1 reflects that of endogenous Glut-1 in hematopoietic cells (25, 26), myc-tagged Glut-1 was stably expressed in the IL-3-dependent Bak−/−Bax−/− cells to achieve highly specific tracking of surface localization of Glut-1. In the absence of tunicamycin, myc-tagged Glut-1 seemed to be on cell surface, but it was largely localized intracellularly after 48 hour tunicamycin treatment (Figure 6C). Flow cytometric analyses further demonstrate that tunicamycin treatment substantially reduced the surface levels of myc-tagged Glut-1, possibly accounting for the reduction of glucose uptake in tunicamycin-treated cells (Figures 6D, 6E). Although unlikely, it is still possible that that trafficking of exogenously expressed Glut-1 is different from that of endogenous Glut-1.

Figure 6. Tunicamycin reduces Glut-1 levels on cell surface and Akt signaling.

(A) IL-3-dependent Bak−/− Bax−/− cells were treated with either 3 µg/ml tunicamycin or DMSO (control). Glut-1 and Hexokinase expression was detected by western blot. (B) Glut-1 expression levels were not reduced by tunicamycin treatment. The intensities of Glut-1 shown in (A) were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH). The data represent means ± S.D. of three independent experiments. (C) Myc-tagged Glut-1 was stably expressed in IL-3-dependent Bak−/− Bax−/−cells. Localization of myc-Glut-1 was examined by immunofluorescence microscopy. Upper panels are bright field images and lower panels are myc-Glut-1 fluorescence images. Scale bar, 10 µM (D) Expression of myc-Glut-1 on cell surface was detected by immunofluorescence staining and flow cytometry. (E) Tunicamycin treatment reduced cell surface myc-Glut-1 levels. The fluorescent intensity of cell surface myc-Glut-1 shown in (D) was normalized with the values of the control cells as 1. The data represent Means ± S.D. of three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate P < 0.05 (*), Student’s paired t test. (F) IL-3-dependent Bak−/−Bax−/− cells were treated with either 3 µg/ml tunicamycin or DMSO (control). The expression of Akt and its down-stream target p70 S6 Kinase was determined by western blot.

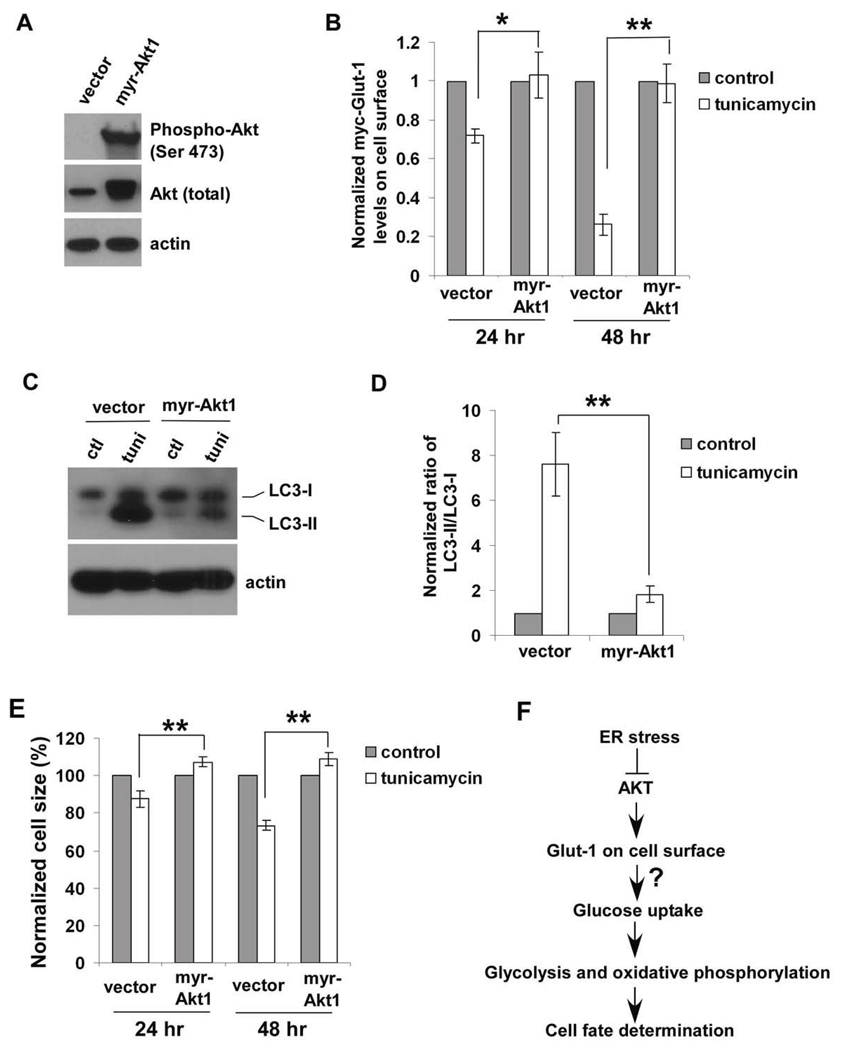

Akt signaling is involved in Glut-1 trafficking and autophagy induction caused by tunicmaycin

As the PI-3K/Akt signaling pathway has been demonstrated to be important for maximal surface expression of Glut-1 (25, 27), we examined whether PI-3K/Akt signaling pathway might be influenced by tunicamycin. At 24 hrs, while the expression levels of Akt and the Akt downstream target p70 S6 Kinase were not significantly affected, phosphorylation of p70 S6 Kinase was completely abolished (Figure 6F), indicating that the Akt signaling pathway was down-regulated in the treated cells. At 48 hrs, both Akt and p70 S6 Kinase expression levels were reduced. These results indicate that tunicamycin down-regulates Akt signaling.

To further elucidate the role of Akt signaling pathway, a constitutively active form of Akt (myristolated Akt1) was exogenously expressed in IL3-dependent Bak−/−Bax−/− cells (Figure 7A). Activated Akt signaling enabled cells to maintain exogenously expressed Glut-1 levels on cell surface, suggesting that tunicamycin-induced decrease in Glut-1 surface levels is caused by Akt inactivation (Figure 7B). Furthermore, myr-Akt1 overexpression largely blocked the conversion of LC3-I form to LC3-II form and cell atrophy caused by tunicamycin, providing evidence that tunicamycin-induced autophagy is blocked by activation of Akt signaling (Figures C, D, E). Thus, reduced Akt signaling is involved in decreased Glut1 surface expression, which might lead to a decrease in glucose uptake and subsequent changes in cellular metabolism and cell fate determination (Figure 6F).

Figure 7. Akt activation abrogates the effects of tunicamycin on Glut-1 trafficking and autophagy induction.

(A) Myristolated Aktl (myr-Aktl) was stably overexpressed in IL-3-dependent Bak−/−Bax−/− cells. The expression of Akt was determined by western blot. (B) The vector control and myr-Aktl-overexpressing cells were treated with either 3 µg/ml tunicamycin or DMSO (control). Cell surface levels of myc-Glut-1 were measured by immunofluorescence staining and flow cytometry. Means ± S.D. of three independent experiments are shown. Asterisks indicate P< 0.05 (*); P < 0.01 (**), Student’s unpaired t test. (C) The effects of activating Akt signaling pathway on expression pattern of LC3 upon 48-hour tunicamycin treatment were determined by western blot. Ctl, control; tuni, tunicamycin. (D) Akt activation blocks the conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II induced by tunicamycin. The intensities of LC3-I and LC3-II shown in (C) were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH). The data represent Means ± S.D. of three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate P < 0.01 (**), Student’s unpaired t test. (E) The sizes of vector control and myr-Aktl-overexpressing cells without or with the treatment of 3 µg/ml tunicamycin were determined by flow cytometry. Means ± S.D. of three independent experiments are shown. Asterisks indicate P < 0.01 (**), Student’s unpaired t test. (F) Tunicamycin influences cellular metabolic processes by down-regulating Akt signaling pathway.

Discussion

We have utilized a NMR-based metabolomics approach to systematically analyze the effects of prolonged ER stress on nutrient utilization, lactic fermentation, and de novo biosynthesis of metabolites that reflect important cellular metabolic processes, including glycolysis, the Krebs cycle, pyrimidine biosynthesis, and the pentose phosphate pathway. In response to sustained ER stress, IL-3-dependent Bak−/−Bax−/− hematopoietic cells demonstrate coordinated bioenergetic responses, leading to an increase in catabolic metabolism and a decrease in anabolic metabolism. As the major carbon source for energy production and anabolic metabolism in IL-3-dependent cells, extracellular glucose consumption decreased upon ER stress. Bioenergetic function of mitochondria in cells undergoing ER stress was compromised, probably as a result of both autophagy and reduced pyruvate supply from glucose oxidation. The observed changes in cellular metabolism could be attributed to the loss of cell surface Glut-1 expression, which is probably caused by down-regulation of Akt signaling pathway.

IL-3-dependent cells deficient in both Bak and Bax were used to investigate ER stress-induced changes in cellular metabolism because, unlike normal cells, these cells will survive exposure to such stress. The inhibition of anaerobic metabolism has been reported to lead to compromised mitochondrial function (28). One example is the reduction in glucose utilization caused by growth factor withdrawal in IL-3-dependent cells, which is associated with disruption of mitochondrial function and subsequent apoptosis (29). In the presence of pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins Bak or Bax, the alterations in glucose metabolism induced by ER stress may lead to decreased mitochondrial membrane integrity and subsequent release of apoptogenic factors, such as cytochrome c, and ultimately apoptosis. Therefore, changes in key cellular metabolic processes revealed in this study could represent a common bioenergetic response to ER stress in hematopoietic cells.

Our systematic analysis of nutrient utilization, lactic fermentation reactions, and de novo biosynthesis of intracellular metabolites has revealed comprehensive information about metabolic changes in IL-3-dependent cells undergoing ER stress-induced autophagy. While the de novo synthesis of metabolites reporting Krebs cycle activities, such as glutamate and aspartate, was significantly reduced in the treated cells, the synthesis of ribose moieties in free nucleotides was almost unchanged, indicating that the pentose phosphate pathway was still active. In addition to generating ribose-5-phosphate used in the synthesis of nucleotides, the pentose phosphate pathway is also critical in producing NADPH from NADP+ in cells. NADPH is required for maintaining the antioxidant activities of reduced glutathione (30). Several recent reports support the importance of the pentose phosphate pathway in protecting cells from death through scavenging toxic free radicals and re-reducing the oxidized biomolecules. For instance, a p53-inducible protein, TIGAR, has been shown to act by lowering ROS levels through the pentose phosphate pathway and protecting against cell death caused by oxidative stress (31). Similarly, NADPH generated by the pentose phosphate pathway is critical for the survival of oocytes in vitro through regulating caspase-2 activity (32). It is conceivable that cells undergoing ER stress must maintain the activity of the pentose phosphate pathway and NADPH levels to survive under autophagic conditions.

The regulation of cellular metabolism by different death stimuli in IL-3-dependent cells has been reported previously and the underlying mechanisms may be distinct and complex (14, 25, 28, 33, 34). Genotoxic drugs inhibit both anaerobic and aerobic metabolism in IL-3-dependent cells, probably due to the reduction in expression levels of Glut-1 and several key enzymes involved in glycolytic metabolism, including hexokinase, phophosfructokinase, and pyruvate kinase (33). In this earlier study, within 4 hrs of drug treatment, reduction of mRNA levels for these proteins could be observed. However, in the present investigations we found that the expression levels of Glut-1 and hexokinase appear unchanged during 48 hrs of tunicamycin treatment. Likewise, total Glut-1 expression level in Bak−/−Bax−/− cells is maintained for at least one week following IL-3 withdrawal (14). Similar to the bioenergetic responses observed in our studies, IL-3 withdrawal also leads to coordinated suppression of glucose utilization and promotion of autophagy (14). Growth factor withdrawal also causes reduction of Glut-1 surface expression (25, 28). As autophagy induced by growth factor withdrawal is essential for maintaining cell survival (14), it is conceivable that the autophagy observed in cells undergoing ER stress could actually be important for cell survival over an extended period of ER stress.

Emerging evidence indicates that ER stress negatively regulates the oncogenic PI-3K/Akt signaling pathway (35–37). GRP78, an ER luminal protein, appears to be a major chaperone able to suppress PI-3K/Akt signaling. Our studies confirm the negative impact of ER stress on PI-3K/Akt signaling with subsequent inhibition of glucose uptake and bioenergetic responses leading to cell fate determination. Although not transformed, Bak−/−Bax−/− cells share important characteristics with cancer cells as they can not undergo apoptosis, an important survival mechanism in cancer cells, but proliferate rapidly in the presence of nutrients and the growth factor IL-3. Furthermore, in the presence of tunicamycin, they exhibit the metabolic characteristics of non-dividing cells that can be maintained in culture under defined conditions. Thus, these apoptosis-deficient cells provide a good model system for investigating the metabolic consequences of cytostasis and transformation in the absence of apoptosis.

A recent elegant study by Wang’s group has identified ENTPD5, an ER UDPase to hydrolyze UDP to UMP, as an integral part of the PI-3K/Akt/PTEN signaling loop (38). Upon Akt activation, ENTPD5 is transcriptionally upregulated to promote protein N-glycosylation and folding in the ER, resulting in the increase in lactate production and cell proliferation. On the other hand, our studies demonstrate that inhibition of protein N-glycosylation by tunicamycin leads to the decreased Akt activities and subsequent reduction of glucose uptake and glycolysis, providing more evidence that targeting protein N-glycosylation in cancer cells could be a potential therapeutic strategy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Andrew Lane at Structural Biology Program, James Graham Brown Cancer Center, University of Louisville for carrying out the NMR experiments, data analysis and intellectual input; Dr. John Eaton (University of Louisville) for critical reading of the manuscript; Dr. Julian Lum (British Columbia Cancer Agency) for helpful discussion; Dr. Arumugam Sen godagounder and Julia Tan for help with NMR experiments. NMR spectra were recorded at the James Graham Brown Cancer Center NMR facility. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health [P20RR018733, K01CA106599, and K01CA106599S1] (CL), funding from the James Graham Brown Cancer Center (CL), and the grant from National Institutes of Health [R01CA123350] (JCR).

Abbreviations

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- IL-3

interleukin-3

- Glut-1

glucose transporter-1

- LC3

microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3

References

- 1.Schroder M, Kaufman RJ. The mammalian unfolded protein response. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005;74:739–789. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogata M, Hino S, Saito A, Morikawa K, Kondo S, Kanemoto S, Murakami T, Taniguchi M, Tanii I, Yoshinaga K, Shiosaka S, Hammarback JA, Urano F, Imaizumi K. Autophagy is activated for cell survival after endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;26:9220–9231. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01453-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heath-Engel HM, Chang NC, Shore GC. The endoplasmic reticulum in apoptosis and autophagy: role of the BCL-2 protein family. Oncogene. 2008;27:6419–6433. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He C, Klionsky DJ. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2009;43:67–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102808-114910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yorimitsu T, Nair U, Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Endoplasmic reticulum stress triggers autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:30299–30304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607007200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li J, Ni M, Lee B, Barron E, Hinton DR, Lee AS. The unfolded protein response regulator GRP78/BiP is required for endoplasmic reticulum integrity and stress-induced autophagy in mammalian cells. Cell Death. Differ. 2008;15:1460–1471. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ding WX, Ni HM, Gao W, Hou YF, Melan MA, Chen X, Stolz DB, Shao ZM, Yin XM. Differential effects of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced autophagy on cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:4702–4710. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609267200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buttgereit F, Brand MD. A hierarchy of ATP-consuming processes in mammalian cells. Biochem. J. 1995;312(Pt 1):163–167. doi: 10.1042/bj3120163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmid D, Burmester GR, Tripmacher R, Kuhnke A, Buttgereit F. Bioenergetics of human peripheral blood mononuclear cell metabolism in quiescent, activated, and glucocorticoid-treated states. Biosci. Rep. 2000;20:289–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1026445108136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang X, Olberding KE, White C, Li C. Bcl-2 proteins regulate ER membrane permeability to luminal proteins during ER stress-induced apoptosis. Cell Death. Differ. 2011;18:38–47. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olberding KE, Wang X, Zhu Y, Pan J, Rai SN, Li C. Actinomycin D synergistically enhances the efficacy of the BH3 mimetic ABT-737 by downregulating Mcl-l expression. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2010;10:918–929. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.9.13274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li C, Wang X, Vais H, Thompson CB, Foskett JK, White C. Apoptosis regulation by Bcl-x(L) modulation of mammalian inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor channel isoform gating. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:12565–12570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702489104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lum JJ, Bauer DE, Kong M, Harris MH, Li C, Lindsten T, Thompson CB. Growth factor regulation of autophagy and cell survival in the absence of apoptosis. Cell. 2005;120:237–248. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan TW, Lane AN, Higashi RM, Farag MA, Gao H, Bousamra M, Miller DM. Altered regulation of metabolic pathways in human lung cancer discerned by (13)C stable isotope-resolved metabolomics (SIRM) Mol. Cancer. 2009;8:41. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan TW, Kucia M, Jankowski K, Higashi RM, Ratajczak J, Ratajczak MZ, Lane AN. Rhabdomyosarcoma cells show an energy producing anabolic metabolic phenotype compared with primary myocytes. Mol. Cancer. 2008;7:79. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-7-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lane AN, Fan TW, Higashi RM. Isotopomer-based metabolomic analysis by NMR and mass spectrometry. Methods Cell Biol. 2008;84:541–588. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(07)84018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lane AN, Fan TW, Higashi RM. Stable isotope-assisted metabolomics in cancer research. IUBMB. Life. 2008;60:124–129. doi: 10.1002/iub.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim I, Xu W, Reed JC. Cell death and endoplasmic reticulum stress: disease relevance and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008;7:1013–1030. doi: 10.1038/nrd2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dorner AJ, Wasley LC, Raney P, Haugejorden S, Green M, Kaufman RJ. The stress response in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Regulation of ERp72 and protein disulfide isomerase expression and secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:22029–22034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scheepers A, Joost HG, Schurmann A. The glucose transporter families SGLT and GLUT: molecular basis of normal and aberrant function. JPEN J. Parenter. Enteral Nutr. 2004;28:364–371. doi: 10.1177/0148607104028005364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao FQ, Keating AF. Functional properties and genomics of glucose transporters. Curr. Genomics. 2007;8:113–128. doi: 10.2174/138920207780368187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rathmell JC, Vander Heiden MG, Harris MH, Frauwirth KA, Thompson CB. In the absence of extrinsic signals, nutrient utilization by lymphocytes is insufficient to maintain either cell size or viability. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:683–692. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frauwirth KA, Thompson CB. Regulation of T lymphocyte metabolism. J. Immunol. 2004;172:4661–4665. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wieman HL, Wofford JA, Rathmell JC. Cytokine stimulation promotes glucose uptake via phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/Akt regulation of Glut1 activity and trafficking. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;18:1437–1446. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-07-0593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wieman HL, Horn SR, Jacobs SR, Altman BJ, Kornbluth S, Rathmell JC. An essential role for the Glut1 PDZ-binding motif in growth factor regulation of Glut1 degradation and trafficking. Biochem. J. 2009;418:345–367. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maciver NJ, Jacobs SR, Wieman HL, Wofford JA, Coloff JL, Rathmell JC. Glucose metabolism in lymphocytes is a regulated process with significant effects on immune cell function and survival. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2008;84:949–957. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0108024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao Y, Wieman HL, Jacobs SR, Rathmell JC. Mechanisms and methods in glucose metabolism and cell death. Methods Enzymol. 2008;442:439–457. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)01422-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vander Heiden MG, Plas DR, Rathmell JC, Fox CJ, Harris MH, Thompson CB. Growth factors can influence cell growth and survival through effects on glucose metabolism. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;21:5899–5912. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.17.5899-5912.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blokhina O, Virolainen E, Fagerstedt KV. Antioxidants, oxidative damage and oxygen deprivation stress: a review. Ann. Bot. 2003;91(Spec No):179–194. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcf118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bensaad K, Tsuruta A, Selak MA, Vidal MN, Nakano K, Bartrons R, Gottlieb E, Vousden KH. TIGAR, a p53-inducible regulator of glycolysis and apoptosis. Cell. 2006;126:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nutt LK, Margolis SS, Jensen M, Herman CE, Dunphy WG, Rathmell JC, Kornbluth S. Metabolic regulation of oocyte cell death through the CaMKII-mediated phosphorylation of caspase-2. Cell. 2005;123:89–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou R, Vander Heiden MG, Rudin CM. Genotoxic exposure is associated with alterations in glucose uptake and metabolism. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3515–3520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Altman BJ, Wofford JA, Zhao Y, Coloff JL, Ferguson EC, Wieman HL, Day AE, Ilkayeva O, Rathmell JC. Autophagy provides nutrients but can lead to Chop-dependent induction of Bim to sensitize growth factor-deprived cells to apoptosis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:1180–1191. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-08-0829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin Y, Wang Z, Liu L, Chen L. Akt is the downstream target of GRP78 in mediating cisplatin resistance in ER stress-tolerant human lung cancer cells. Lung Cancer. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qin L, Wang Z, Tao L, Wang Y. ER stress negatively regulates AKT/TSC/mTOR pathway to enhance autophagy. Autophagy. 2010;6:239–247. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.2.11062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfaffenbach KT, Lee AS. The critical role of GRP78 in physiologic and pathologic stress. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fang M, Shen Z, Huang S, Zhao L, Chen S, Mak TW, Wang X. The ER UDPase ENTPD5 promotes protein N-glycosylation, the Warburg effect, and proliferation in the PTEN pathway. Cell. 2010;143:711–724. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.