Abstract

A new type of pH-labile cationic polymers, poly(ortho ester amidine) (POEAmd) copolymers, has been synthesized and characterized with potential future application as gene delivery carriers. The acid-labile POEAmd copolymer was synthesized by polycondensation of a new ortho ester diamine monomer with dimethylaliphatimidates, and a non-acid-labile polyamidine (PAmd) copolymer was also synthesized for comparison using a triethylene glycol diamine monomer. Both copolymers were easily dissolved in water, and can efficiently bind and condense plasmid DNA at neutral pH, forming nano-scale polyplexes. The physico-chemical properties of the polyplexes have been studied using dynamic light scattering, gel electrophoresis, ethidium bromide exclusion, and heparin competition. The average size of the polyplexes was dependent on the amidine: phosphate (N:P) ratio of the polymers to DNA. Polyplexes containing the acid-labile POEAmd or the non-acid-labile PAmd showed similar average particle size, comparable strength of condensing DNA, and resistance to electrostatic destabilization. They also share similar metabolic toxicity to cells as measured by MTT assay. Importantly, the acid-labile polyplexes undergo accelerated polymer degradation at mildly-acid-pHs, resulting in increasing particle size and the release of intact DNA plasmid. Polyplexes from both types of polyamidines caused distinct changes in the scattering properties of Baby Hamster Kidney (BHK-21) cells, showing swelling and increasing intracellular granularity. These cellular responses are uniquely different from other cationic polymers such as polyethylenimine and point to stress-related mechanisms specific to the polyamidines. Gene transfection of BHK-21 cells was evaluated by flow cytometry. The positive yet modest transfection efficiency by the polyamidines (acid-labile and non-acid-labile alike) underscores the importance of balancing polymer degradation and DNA release with endosomal escape. Insights gained from studying such acid-labile polyamidine-based DNA carriers and their interaction with cells may contribute to improved design of practically useful gene delivery systems.

Keywords: Copolymer, Ortho ester, Gene delivery

1. Introduction

Non-viral vectors based on cationic polymers have gained significant attention over the past decades for the delivery of nucleic acids in gene therapy due to many potential advantages, such as large DNA loading capacity, ease of large-scale production, and reduced immunogenicity which has been a key issue associated with the use of viral vectors [1]. A wide variety of cationic polymers have been developed for gene delivery, such as poly(L-lysine) (PLL), poly(ethylenimine) (PEI), poly(amidoamine) dendrimer, etc [2]. These cationic polymers can condense DNA and form stable polymer/DNA complexes via electrostatic interaction and protect nucleic acids from enzymatic digestion, providing unlimited DNA packaging capacity, well-defined physicochemical properties, and a high degree of molecular diversity that allows extensive modifications to overcome extracellular and intracellular obstacles of gene delivery [3]. Research efforts are currently focused on development of safe and efficient polymeric carriers that can form complex with DNA and can avoid biological barriers for gene delivery [4]. Among the main barriers for non-viral gene delivery, endosomal escape and release of nucleic acids from the carriers once arrived at target sites are crucial efficiency-determining steps [5, 6].

Hydrolysis of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) energizes the ion-transport processes across the cell membrane, and in turn makes the endosomal and lysosomal compartments of cells significantly more acidic (pH 5.0-6.2) than the cytosol or intracellular space (∼pH 7.4) [7]. Remarkably, some viruses have evolved to use pH-sensitive peptides to facilitate their escape from the endosomes, resulting in high gene transfection [8]. Non-viral DNA vectors that utilize this significant drop in pH of endosomes and lysosomes often show improved gene transfection, and several designing strategies of “smart” cationic polymers have been successfully developed. The most used method is to create polymer blocks with amine groups with low pKa values around 5 that have been shown to exhibit “proton sponge” potential, and these compounds are able to buffer the endosome and results in endosomal swelling and lysis, thus in turn releasing the DNA into the cytoplasm [9-13]. Similarly, incorporation of chloroquine into the DNA/vector complex often exhibit efficient gene transfection, because chloroquine is a well-known lysosomotropic agent that raises the pH of lysosomal environment, in turn hampering the enzymes involved in lysosomal degradation [14-16]. Another strategy developed recently is the incorporation of amine groups with acid-labile linkages, such as β-amino esters [17, 18], acetal [19, 20], ketal [21, 22] and vinyl ether [23, 24] into the polymer main-chains, where the endosomal acidic environment can hydrolyze the linker group to yield fragmentation products that raise the osmotic pressure within the vesicles, causing leakage and release. There is considerable flexibility in the design of pH-responsive cationic polymer vectors, where different linkage configurations can be implemented to generate desired physicochemical properties, and different hydrolysis kinetics and hydrolyzed products can be designed with different membrane-destabilizing capacities.

Poly(ortho esters) (POEs) are an important type of acid-labile polymers with excellent biocompatibility [25-28]. Compared to vinyl ether and acetal and ketal, the ortho ester bond hydrolyzes more quickly in response to mildly acid condition [25, 26, 29]. We are interested in designing non-viral polymeric gene delivery vectors through the incorporation of ortho ester linker with functional groups containing positive charges. Recently, Davis et al. reported the synthesis of sugar-containing cationic polyamidine-based copolymers and their application in gene delivery with relatively high transfection efficiency and high cytotoxicity [30, 31]. These polyamidines are not known to degrade readily and they are insensitive to endosomal acidic pH. In this study, we focus on a new type of acid-labile polyamidine-based copolymer system with the introduction of ortho ester into the copolymer main-chains, which may potentially serve as a molecular platform for the elucidation of the relationship between endosomal escape of polymer-DNA complex and DNA release triggered by pH-sensitive polymer degradation in the context of gene delivery. We hypothesized that incorporation of ortho esters to the polymer main-chains would facilitate efficient gene delivery via enhanced endosomal escape of complex and release of DNA. Hydrolysis of ortho esters in the mildly acidic endosomes would increase osmotic pressure and swelling of the carriers, which is expected to help to supplement the poor buffering capacity of polyamidines due to their pKa values as high as about 11 [32] and to efficiently unpack nucleic acids due to the dissociation of copolymer vectors. Here we report the synthesis of the new polyamidine-based copolymers, poly(ortho ester amidines) (POEAmd), and the results of physico-chemical characterization of copolymer/DNA plasmid polyplexes, including pH-triggered DNA release. We also characterized in vitro interactions of the polyplexes with Baby Hamster Kidney (BHK-21) cells (including cytotoxicity, cell morphology, and gene transfection), aiming to illustrate how the structure of pH-sensitive acid-labile polymeric vectors may influence the function of delivering DNA to cells.

2. Experimental section

2.1. General methods of characterization

The 1H and 13C- NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Unity spectrometer (300 MHz), and chemical shifts were recorded in ppm. High-resolution mass spectra in electrospray-ionization (ESI) experiments were obtained on a Bruker MicrOTOF-Q mass spectrometer. Elemental analysis was conducted on a Carlo Erba 1108 automatic analyzer. The molecular weight and polydispersity of copolymers were determined by aqueous GPC analysis relative to PEG standard calibration (Waters 1525 binary HPLC pump, a Waters 2414 differential refractometer, and a Waters YMC HPLC column) using a mixture of 0.5 M NaNO3 and 0.1 M Tris buffer (pH 7.2) as eluent at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min at 35°C. All sample solutions were filtered through a 0.45 μm filter before analysis.

2.2. Materials

Tetrahydrofuran (THF) was distilled over sodium and benzophenone, and acetonitrile was dried by distillation over CaH2. 5-Trifluoroacetylaminopentanol was synthesized as described previously [27]. All other solvents and reagents were analytical-grade, purchased commercially, and used without further purification.

2.3. Synthesis

2,2,2-Trifluoro-N-(2,3-dihydroxypropyl) acetamide (1)

To a stirred mixture of 3-amino-1,2-propanediol (18.80 g, 0.21 mol) in acetonitrile (120 mL) under argon was added dropwise ethyl trifluoroacetate (34.30 g, 0.24 mol). After 4 h, the solvent was evaporated, and the residue was dissolved in ethyl acetate (200 mL), washed with aqueous KHSO4 and brine, then dried over MgSO4, and concentrated to yield 34.90 g (91%) of 2,2,2-trifluoro-N-(2,3-dihydroxypropyl)-acetamide as colorless oil. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD3OD): δ (ppm) 3.27-3.29 (m, 2H, NH-CH2), 3.47-3.49 (m, 2H, CH2-OH), 3.70-3.78 (m, 1H, CH-OH), 7.60 (b, 1H, NH).

2,2,2-Trifluoro-N-(2-methoxy-[1,3]-dioxolan-4-ylmethyl) acetamide (2)

To a stirred mixture of 1 (13.50 g, 72.15 mmol), trimethyl orthoformate (34.89 g, 0.33 mol), and acetonitrile (110 mL) was added p-toluene sulfonic acid (p-TSA; a trace amount). The mixture was reacted for 6 h at room temperature, followed by evaporation of most of volatile components. The residue was dissolved in ethyl acetate (250 mL), washed successively with saturated aqueous sodium hydrogen carbonate and brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated to yield 14.55 g (88%) of 2,2,2-trifluoro-N-(2-methoxy-[1,3] dioxolan-4-ylmethyl) acetamide as oil. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 3.34-3.40 (d, 3H, O-CH3), 3.45-3.71 (m, 2H, NH-CH2), 4.15-4.25 (m, 2H, O-CH2), 4.46-4.53 (m, 1H, O-CH), 5.74-5.79 (d, 1H, CHOCH3), 6.70-7.64 (b, 1H, NH).

2,2,2-Trifluoro-N-(2-(5′-trifluoroacetylaminopentyloxy)-[1,3]-dioxolan-4-ylmethyl) acetamide (3)

A mixture of 2 (9.90 g, 43.20 mmol), 5-trifluoroacetylaminopentanol (8.60 g, 43.20 mmol), and pyridinium p-toluene sulfonate (110.00 mg, 0.44 mmol) was heated at 130°C until no volatile component was distilled. After cooling to room temperature, the residue was purified with column chromatography (silica gel, ethyl acetate/hexane (1/1) as eluent) to yield 15.41 g (90%) of 2,2,2-trifluoro-N-(2-(5′-trifluoroacetylaminopentyloxy)-[1,3]dioxolan-4-ylmethyl) acetamide as oil. 1H NMR (300MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 1.39-1.44 (t, 2H, CH2), 1.51-1.62 (m, 4H, CH2), 3.35-3.38 (m, 2H, NH-CH2), 3.62-3.65 (m, 2H, NH-CH2), 4.05-4.17 (m, 2H, O-CH2), 4.31-4.37 (m, 1H, O-CH), 5.71-5.78 (d, 1H, CHOCH3), 6.73-6.95 (b, 1H, NH), 7.25-7.51 (b, 1H, NH).

4-Aminomethyl-2-aminopentyloxy-[1,3]-dioxolan (Monomer)

The trifluoroacetamide 3 (13.35 g, 33.70 mmol) was dissolved in THF (90 mL), and sodium hydroxide (2.0 M, 75 mL) was added. The mixture was vigorously stirred overnight, extracted with diethyl ether, dried over MgSO4, and evaporated. The residue was purified with column chromatography (silica gel, methanol/dichloromethane (1/10) as eluent) to yield 6.08 g (88%) of 4-aminomethyl-2-aminopentyloxy-[1,3]-dioxolan as oil. 1H NMR (300MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 1.35-1.61 (m, 6H, CH2), 2.70-2.90 (m, 4H, CH2-NH2), 3.48-3.79 (m, 4H, O-CH2), 4.02-4.09 (m, 1H, O-CH). 5.80-5.86 (d, 1H, CHOCH3); 13C NMR (CDCl3, δ ppm): 23.12, 29.39, 33.30, 33.51, 42.08, 44.42, 62.28, 67.14, 70.95, 78.33, 115.45, 115.79; Calcd: (C9H20N2O3) 204.3, found m/z 205.2 (M + H+), Anal. Calcd for (C9H20N2O3): C, 52.92; H, 9.87; N, 13.71. Found: C, 52.84; H, 9.80; N, 13.65.

Synthesis of acid-labile poly(ortho ester amidines) (POEAmd 1∼3)

The copolymers (POEAmd 1∼3) were synthesized using the same procedure of polycondensation, and the synthesis of POEAmd 1 is described here as an example: dimethyladipimidate dihydrochloride (0.60 g, 2.45 mmol) was added to a stirred mixture of the monomer (0.50 g, 2.45 mmol) and 0.5 M Na2CO3 aqueous solution (0.90 mL, 4.50 mmol) under argon, reacted for 24 h at room temperature, and placed in a semi-permeable dialysis membrane (MW cut-off: 3500), and dialyzed against distilled water with a trace amount of triethylamine for 24 h. The obtained POEAmd 1 was lyophilized, and the molecular weight and polydispersity of the product was determined by aqueous GPC.

Synthesis of non-acid-labile polyamidines (PAmd 1∼3)

The copolymers (PAmd 1∼3) were synthesized using the same procedure of polycondensation, and the synthesis of PAmd 1 is described here as an example: dimethyladipimidate dihydrochloride (0.56 g, 2.27 mmol) was added to a stirred mixture of the 4,7,10-trioxa-1,13-tridecanediamine (0.50 g, 2.27 mmol) and 0.5 M NaCO3 aqueous solution (0.90 mL, 4.50 mmol) under argon, reacted for 24 h at room temperature, and placed in a semi-permeable dialysis membrane (MW cut-off: 3500), and dialyzed against distilled water for 24 h. The obtained PAmd 1 was lyophilized, and the molecular weight and polydispersity of the product was determined by aqueous GPC.

2.4. Determination of the mechanism and rate of hydrolysis of the poly(ortho ester amidine)

POEAmd 1 copolymer was dissolved in 150 mM d-phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and d-acetate buffers (150 mM, pH 6, 5, and 4) at 5 mg/mL, and the 1H-NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Unity spectrometer (300 MHz) at different time points. The rate of hydrolysis of the ortho ester in the polymer main-chain was calculated as the ratio (percentage) of the integrated area of the NMR peak at 8.01 ppm to the sum of the areas of peaks at 8.01 and 5.79 ppm.

2.5. Preparation of polyplexes and gel retardation assay

Polymer/DNA complexes (polyplexes) of N:P ratios ranging from 1:8 to 24:1 were prepared by adding 25 μL of polymer solution in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) to 25 μL of DNA plasmid solution (0.2 μg/μL in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4), vortexed for 10 seconds, and the dispersions were incubated for 30 min at room temperature. To ascertain DNA binding, the polyplexes were analyzed by gel electrophoresis on a 1.0% agarose gel containing 0.5 μg/mL ethidium bromide. To determine the strength of DNA binding by copolymers, polyplexes at N:P ratio of 8:1 were incubated with increasing concentrations of heparin (0.1∼1.5 IU per μg of DNA) for 10 min at room temperature and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. To determine the stability of polyplex under acidic pH condition, polyplexes at N:P ratio of 8:1 were incubated overnight in pH 7.4 and 5 (50 mM phosphate and acetate buffers, respectively) at room temperature, and visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis.

2.6. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) and zeta-potential measurements

The average hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity index of polyplexes in HEPES buffer (20 mM, pH 7.4) at 25°C were determined using a ZetaPlus Particle Analyzer (Brookhaven Instruments Corporation, Holtsville, NY; 27 mW lasers; 658 nm incident beams, 90° scattering angle). Polyplexes with N:P ratios ranging from 1:4 to 24:1 were prepared as described above and diluted 20 times to a final volume of 2 mL in HEPES buffer before measurement. Simultaneously the zeta-potential of the polyplexes was determined using the ZetaPal module of the Particle Analyzer. To determine colloidal stability of polyplexes against different pH values, polyplexes of N:P ratio of 8:1 was incubated in 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and 20 mM acetate buffers (pH 6, 5, and 4), and the change in average hydrodynamic diameter of the polyplexes was monitored continuously for up to 40 min.

2.7. Ethidium bromide exclusion assay

The effect of the N:P ratio on the degree of plasmid DNA condensation in polyplex was estimated from the reduction in fluorescence intensity of ethidium bromide (EtBr) due to the exclusion from condensed DNA. EtBr solutions (1%, 8 μL) were added into the polymer/DNA complex solution (10 μg of plasmid DNA, 100 μL) prepared at various N:P ratios. After 15 min, 200 μL of the polyplexes were added to a 96-well plate, and the decrease in EtBr fluorescence intensity was measured in triplicates as described previously [33] using a Bio-Tek Synergy HT plate reader with excitation wavelength at 518 nm and an emission wavelength of 605 nm. Results were expressed as relative fluorescence intensity. The fluorescence intensity of uncondensed plasmid DNA solution with EtBr was set at 100%, after correction of the background of EtBr without plasmid DNA.

2.8. Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity of the polyplexes was evaluated by an MTT (3-(4,5-dimethyl-thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) assay [34]. Baby hamster kidney (BHK-21) cells (ATCC) were seeded into 96-well plates at 10000 cells/well and cultured with polyplexes of various concentrations for 24 h in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 mM HEPES, 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin at 5% CO2 and 37°C. MTT in PBS (5 mg/mL, 20 μL) was added to each well reaching a final concentration of 0.5 mg/mL. After 4 h unreacted MTT was removed by aspiration. The formazan crystals were dissolved in 100 μL of DMSO and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a Bio-Tek Synergy HT plate reader. Cell viability was calculated by [Absorbance of cells exposed to polyplexes] / [Absorbance of cells cultured without polyplexes] in percentage.

2.9. In vitro transfection and the effect on cell morphology

To prepare polyplexes for in vitro transfection, polymers were mixed with plasmid DNA containing a CMV promoter and a green fluorescence protein reporter gene (pCMV-EGFP, purchased from Elim Biopharmaceuticals) at N:P ratios of 4:1, 8:1, and 16:1. BHK-21 cells were seeded in 6-well plates with a density of 100,000 cells per well and cultured for 24 h before polyplexes were added. Afterwards polyplexes were added at 4 μg DNA per well in 2 mL of serum-free media, and incubated for 4 h. The polyplex containing media was then discarded and the cells were washed by DPBS and cultured in fresh media with 10% serum for 20 h. The cells were then trypsinized and harvested in FACS buffer (DPBS with 1% BSA, 0.1% NaN3).The percentage of transfected cells was determined by measuring GFP expression in the cell population using a FACSCalibur 501 flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter). The GFP positive gate was set based on the cell population treated with polyplexes containing firefly luciferase plasmid, which does not produce GFP, to compensate for potential change in cell autofluorescence due to exposure to cationic polymers. The front and side scattering of light by the cells exposed to polyplexes with different N:P ratios were also determined.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Synthesis and characterization of POEAmd copolymers

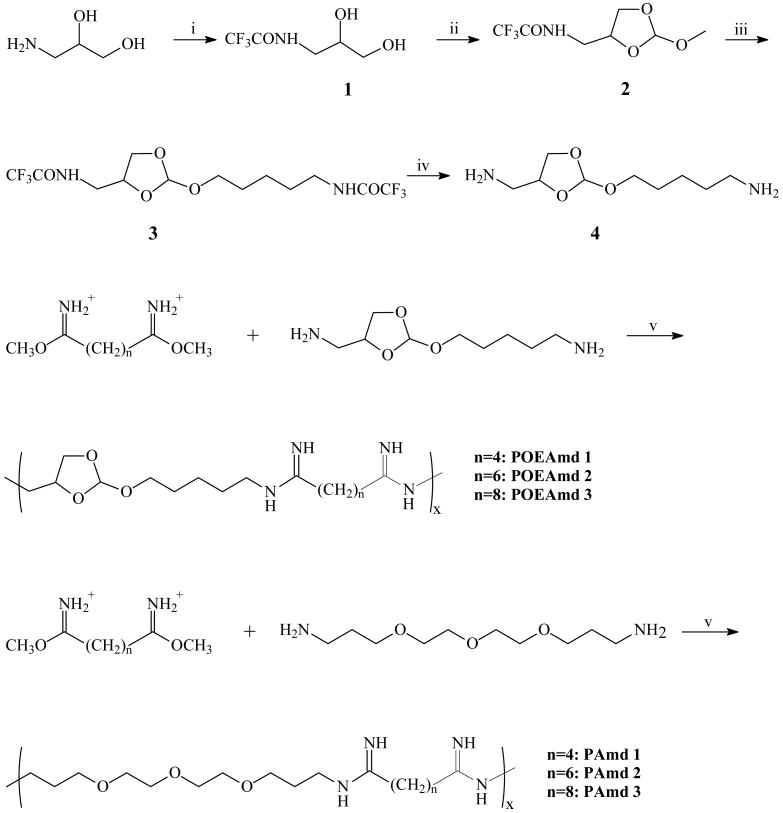

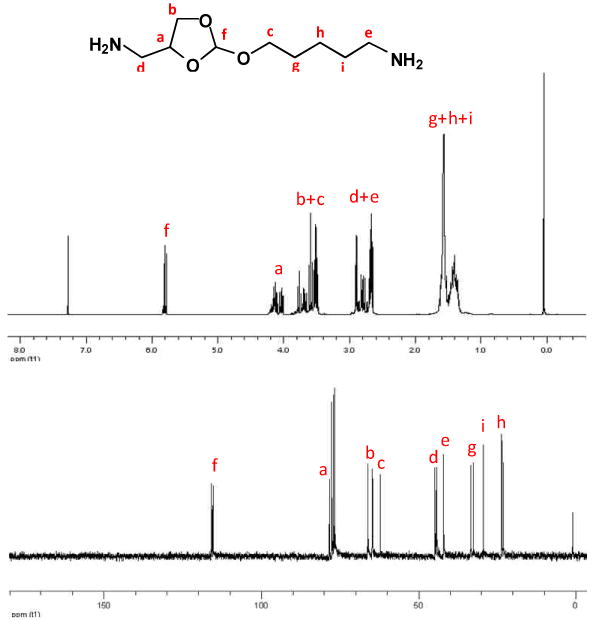

The key acid-labile ortho ester diamine monomer was synthesized in four steps (Scheme 1): 2,2,2-trifluoro-N-(2,3-dihydroxypropyl) acetamide (1) was obtained by using 3-amino-1,2-propanediol as the starting material, which then reacted with trimethyl orthoformate in the presence of catalytic p-toluenesulfonic acid to give the ortho ester 2. The compound 3 was easily obtained by transesterification between compound 2 and trifluoroacetylaminopentanol. The TFA-protecting groups of compound 3 were removed by aqueous sodium hydroxide in THF, and the acid-labile bifunctional monomer was easily obtained with the total yield of approximately 63%. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra confirmed that the monomer was pure and structurally correct (Fig. 1). The highly hydrolytically labile ortho ester is built into the monomer, and is stabilized by the neighboring primary amines, allowing for easy handling and long-term storage. The diamine monomer can be copolymerized readily with any multifunctional amine-reactive monomers to produce a range of structurally and functionally diverse, biodegradable copolymers, for examples, poly(ortho ester amides) [27] and poly(ortho ester amidines) as reported here.

Scheme 1a.

a Reagents and conditions: (i) Ethyl trifluoroacetate, acetonitrile; ii) Trimethyl orthoformate, p-toluene sulfonic acid (p-TSA), acetonitrile; (iii) 5-trifluoroacetylamino-1-pentanol, pyridinium p-TSA; (iv) NaOH/H2O/THF; (v) 0.5 M Na2CO3

Fig. 1.

1H and 13C-NMR spectra of the ortho ester diamine monomer.

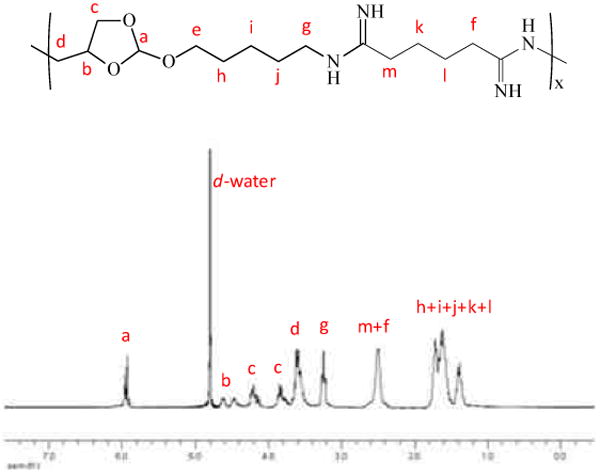

We synthesized poly(ortho ester amidines) (POEAmd) via polycondensation of the acid-labile ortho ester diamine monomer with dimethylaliphatimidate dihydrochloride with different alkyl groups (Scheme 1). Similarly, we also synthesized a series of non-acid-labile polyamidines (PAmd) by polycondensation of 4,7,10-trioxa-1,13-tridecanediamine with various dimethylaliphatimidates. POEAmd 1 and PAmd 1 copolymers were easily dissolved in water, and their chemical structures were confirmed by 1H-NMR (Fig. 2). However, other POEAmd and PAmd copolymers were not soluble in water, probably due to the increased hydrophobicity resulted from increased length of alkyl groups. The average number molecular weight and distribution of POEAmd 1 and PAmd 1 were determined by GPC, and calculated to be 6500 and 6800 with polydispersity index of 1.81 and 1.95, relatively, as shown in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

1H-NMR spectrum of POEAmd 1.

Table 1.

Polymerization results of POEAmd and PAmd copolymers.

| Polymer | Yield (%) | Mn (×10-4) | Mw (×10-4) | PDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POEAmd 1 | 55 | 0.65 | 1.18 | 1.81 |

| PAmd 1 | 51 | 0.68 | 1.33 | 1.95 |

3.2. Kinetics of Polymer Hydrolysis and pH-Dependence

Ortho ester structures are highly hydrolytically labile and acid-sensitive [35]. There are two possible pathways of hydrolysis for cyclic ortho esters that involve exocyclic and endocyclic breakage of the ortho ester bond [25, 26]. In a recent report, trans-N-(2-ethyoxy-1,3-dioxan-5-yl)methacrylamide, a monomer containing a six-membered cyclic ortho ester, was incorporated in block copolymer micelles [36]. This ortho ester hydrolyzed through both exocyclic and endocyclic pathways, giving rise to a mixture of two chemically distinct products with different solubility in water [37]. Our group have recently developed novel micelle-like nanoparticles based on pH-responsive copolymers, poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(N-(2-methoxy-[1,3]dioxolan-4-ylmethyl) methacrylamides) (PEG-b-PMYM), whose hydrolysis of the ortho ester side-chains follows a distinct exocyclic mechanism and shows pH-dependent kinetics confirmed by 1H-NMR spectra [29]. Here the five-membered ortho ester group from the side-chains of the PMYM block [29] has been built into the main-chain of the poly(ortho ester amidine) copolymer, POEAmd 1.

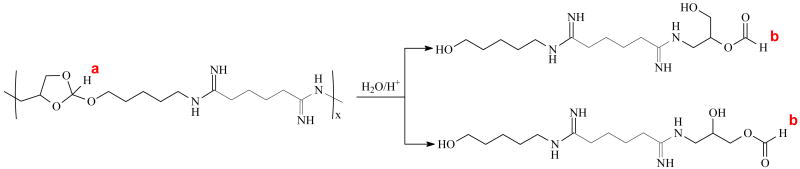

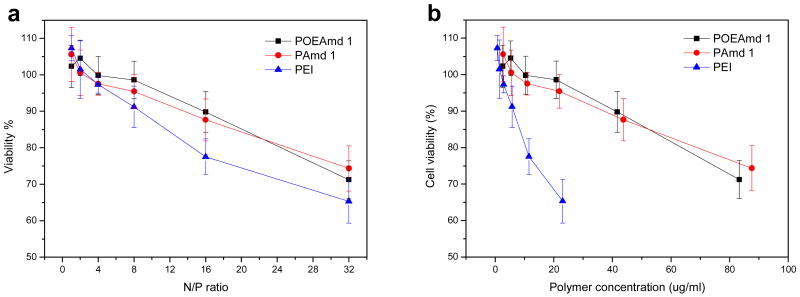

To understand the hydrolytic mechanism of POEAmd 1, NMR studies were carried out to follow the time-course of hydrolysis for up to 48 h in aqueous buffers of physiological (pH 7.4) and mildly acidic pHs (6, 5, and 4), and the results are shown in Fig. 3. The peak at 5.79 ppm (denoted as “a”) is characteristic of the ortho ester proton before hydrolysis (Scheme 2). At pH 7.4 over the course of 48 h, the area of peak “a” decreased only slightly, suggesting that only a small amount of the ortho ester hydrolyzed and that most of the ortho ester groups remained intact. Concurrently, a new peak at 8.01 ppm (denoted as “b”) appeared after approximately 24 h (Fig. 3), which corresponds to the proton of formate. The endocyclic pathway of hydrolysis would produce two different kinds of formate, one appended to the copolymer and a small molecule, methyl formate, whereas the exocyclic pathway should yield only the polymeric formate (Scheme 2). Here we observed a single formate peak between 8 and 8.2 ppm even after extensive hydrolysis at pH 4 for 48 h (Fig. 3), demonstrating that the hydrolysis of POEAmd 1 follows the exocyclic pathway exclusively, unlike the six-membered ortho ester ring structure reported before [37]. This finding agrees with previous studies on other related cyclic ortho esters and may be attributed to the unique stereoelectronic and steric effects of the ring structure [25, 29, 38].

Fig. 3.

1H NMR spectra of POEAmd 1 (5 mg/mL) in d-buffers of pH 7.4, 6, 5, and 4, at different time points up to 48 h. Peaks labeled with “a” and “b” are protons characteristic to the cyclic ortho ester and formate groups, respectively (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Furthermore, we found that at all time points and all pHs, the increase in the integral area of peak “b” was equal to the decrease of peak “a”, and that the sum of the two peaks remained constant (Fig. 3). Taken together, the NMR data confirm that the ortho ester structure of POEAmd 1 copolymer undergo exocyclic cleavage, and are converted quantitatively to a pair of stereo-isomers containing a hydroxyl and a formate (Scheme 2). The progression of ortho ester hydrolysis is revealed by the NMR analysis (Fig. 3) and can be quantified based on the changing integral area of peak “a” (representing the ortho ester proton before hydrolysis) and peak “b” (representing the formate proton as a result of hydrolysis). We define the degree of hydrolysis to be the percentage of peak “b” relative to the sum of the peaks “a” and “b”. The time/pH-dependence of hydrolysis is shown spectroscopically in Figure 3 and quantitatively in Fig. 4. As expected, hydrolysis of the ortho ester structure is highly sensitive to pH and is much accelerated at more acidic pHs. At pH 7.4 and 6, 5% and 81% of the ortho esters were hydrolyzed within 48 h, whereas the hydrolysis was essentially complete in 48 and 8 h when pH was lowered to 5 and 4, respectively (Fig. 3). The ability of achieving markedly different hydrolysis kinetics from days to hours over a fairly narrow pH range (from 7.4 to 4), as we have demonstrated here, bodes well for the potential of using such polymer systems for pH-triggered gene delivery.

Fig. 4.

Time and pH-dependence of ortho ester hydrolysis in POEAmd 1 based on the NMR spectra shown in Fig. 3.

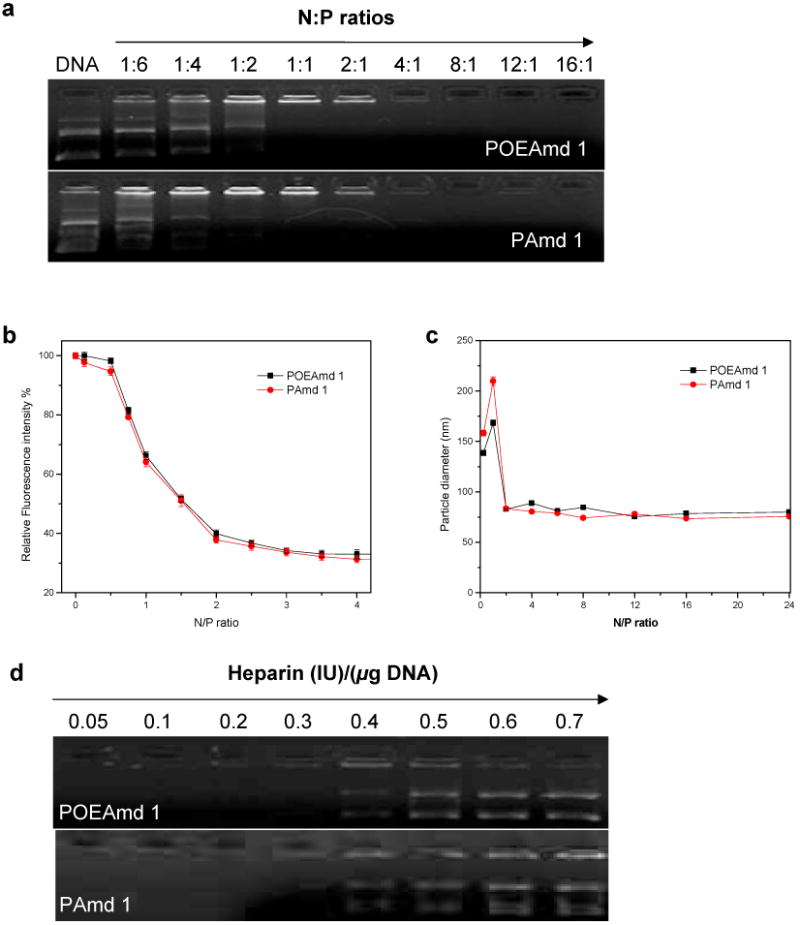

3.3. DNA binding and condensation

Gel retardation assay shows that POEAmd 1 and PAmd 1 copolymers were both able to bind to and completely neutralize the negative charges of a DNA plasmid at the N:P ratio of 1:1 and beyond, as shown in Fig. 5a. The polymer-DNA condensation can be characterized by the quenching of the fluorescence of ethidium bromide (EtBr) due to the formation of complexes, where charge neutralization and subsequent condensation of DNA prevents EtBr from intercalating into DNA double-helix. As shown in Fig. 5b, the fluorescence intensity of EtBr decreased with an increase in the N:P ratio and reached a minimum at about N:P of 2, which was consistent with the progressive complexation of copolymer with plasmid DNA, inhibiting the intercalation of EtBr into plasmid DNA. DLS reveals that the average particle size of polyplexes in aqueous buffer spanned almost the same range of 75 to 210 nm with much dependence on the N:P ratio (Fig. 5c). The size distribution of each type of polyplex was also quite narrow with PDI ranging from 0.05 to 0.25. At N:P ratio of 1:1, average particle size stabilizes around 160-210 nm for these two polyplexes (Fig. 5c), and greatly decrease to be about 80 nm when the N:P ratio is above 1:1. Polyplexes formed by POEAmd 1 and PAmd 1 had similar zeta-potential values (49.95±6.68 mV and 47.04±4.48 mV, respectively). Discrete, compact polyplexes formed at N:P ratio of 8:1 (Fig. 5c) were selected for further characterization to understand the polyplex stability in physiological conditions. The polyplexes were further analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis after incubation with increasing amount of heparin, a polyanion that can compete with DNA for the binding to the polycation. As shown in Fig. 5d, the threshold concentration of heparin at which polyplex disruption occurred was 0.4 IU for polyplexes of both POEAmd 1 and PAmd 1. Taken together, these results illustrate the ability of using polyamidine-based copolymers to control the formation of defined and narrowly dispersed polyplexes, which is highly important in light of the notion that cell-specific targeting and internalization can be much affected by the size of the particulates [39, 40].

Fig. 5.

Characterization of plasmid DNA binding and condensation by POEAmd 1 and PAmd 1. (a) Gel retardation assay of polyplexes prepared at various N:P ratios; (b) Estimation of plasmid DNA condensation by ethidium bromide exclusion assay; (c) DLS determination of the average particle size of polyplexes in aqueous buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) as a function of N:P ratio; (d) Dissociation of DNA from polymers induced by increasing amount of heparin.

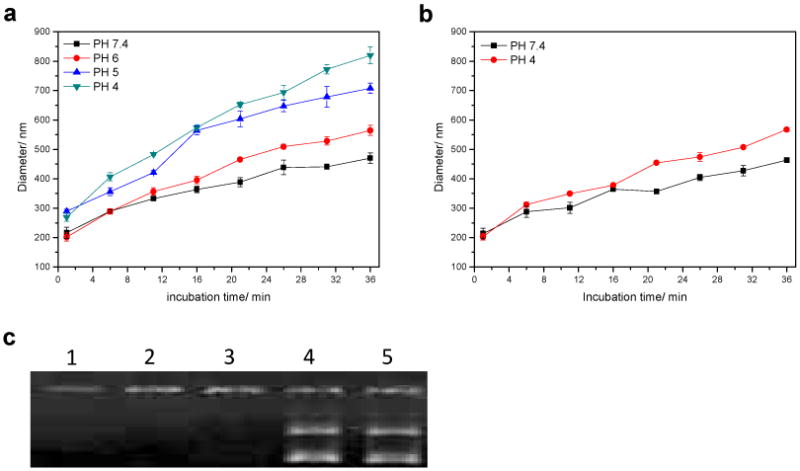

3.4 Stability of polyplexes and acid-triggered DNA release

The stability of polyplexes at N:P ratio of 8:1 was studied in phosphate and acetate buffers (20 mM, pH 7.4, 6, 5 and 4), and in the presence of increasing amount of heparin at physiological ionic strength (150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4). First, the average size dependence of polyplexes on incubation time was determined by DLS measurements in different pH conditions. Due to the hydrolysis of POEAmd 1 in mildly acidic conditions, polyplexes formed by POEAmd 1 rapidly dissociate, and the size greatly increased to be 700∼800 nm in 36 min at pH 5 and 4 (Fig. 6a). On the contrary, polyplexes formed by non-acid-labile PAmd 1 only enlarged slightly even at pH 4 over the same period of time (Fig. 6b). To determine if polymer hydrolysis at acidic pH does trigger the release of DNA, the polyplexes were exposed to pH 7.4 and 5 and then analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. DNA remained bound to the non-acid-labile PAmd 1 regardless of pH (Fig. 6c). However, the acid-labile POEAmd 1 bound to DNA stably at pH 7.4 and released free DNA at pH 5, presumably due to the polymer degradation and the subsequent loss of DNA condensation. Both DLS and gel electrophoresis experiments demonstrated that acid-labile ortho ester linkages in the polymer main-chain has a profound impact on the colloidal stability of polyplexes and that acid-pH-triggered DNA release can be achieved by the acid-labile poly(ortho ester amidine).

Fig. 6.

Stability of polyplexes at N:P ratio of 8:1. (a) Time-dependent stability of polyplexes formed from the acid-labile POEAmd 1 in different pHs; (b) Stability of DNA from the non-acid-labile PAmd 1 in different pHs; (c) Gel retardation assay of stability of polyplexes; lane 1: PAmd 1/DNA, pH 7.4; lane 2: POEAmd 1/DNA, pH 7.4; lane 3: PAmd 1/DNA, pH 5; lane 4: POEAmd 1/DNA, pH 5; line 5: Plasmid DNA only, pH 7.4.

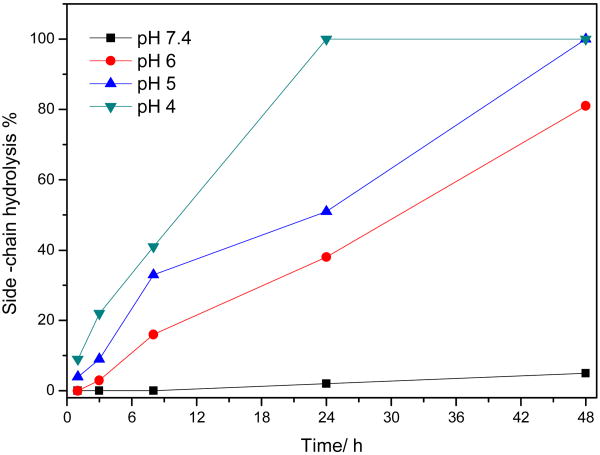

3.5 In vitro cytotoxicity and gene transfection

BHK-21 cells were used for the evaluation of in vitro toxicity and transfection of the polyplexes formed from POEAmd 1 and PAmd 1, and branched polyethylenimine (PEI) (Mw: 25 kDa) as a control. At N:P ratio of 16:1 or less, the polyplexes formed from POEAmd 1 and PAmd 1 were not toxic to BHK-21 cells (Fig. 7a). In contrast, polyplexes formed by branched PEI was more toxic, killing much of BHK-21 cells at N:P ratio of 16:1 (Fig. 7a). When N:P ratio exceeded 16:1, all polyplexes formed from polymers including POEAmd 1 and PAmd 1 showed some toxicity, which is consistent with that of polyamidine-based copolymers [30, 31]. The difference in cytotoxicity between the polyamidines and PEI was more pronounced when comparing these polymers at equivalent mass. For example, mass concentration of 20 µ g/mL of PEI reduced cell viability to 65%, yet at the same mass concentration of the polyamidines, cell viability was higher than 95% (Fig. 7b). These results suggest that compared to branched PEI, the polyamidines appear much less toxic to cells and that both the acid-labile and non-acid-labile polymers share similar cytotoxicity.

Fig. 7.

Cytotoxicity of polyplexes in BHK-21 cells determined using an MTT assay. (a) Polyplexes at various N:P ratios; (b) Polyplexes by mass concentration. Cells treated with culture media only were taken as the 100% viability.

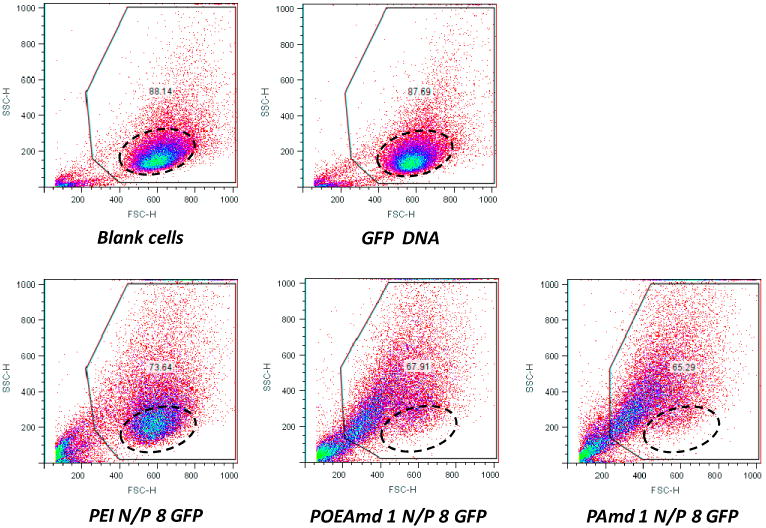

The effect on the BHK-21 cells by polyplex formed from POEAmd 1 and PAmd 1 were further assessed by examining the light scattering properties of the cells under transfection conditions, as shown in Fig. 8. Generally, front scattering intensity correlates with the size of cells, and side-scattering intensity correlates with the granularity or internal structure of cells. Untreated normal cell population within the “live” gate shows a single population with certain scattering properties: the majority of cells have front scatter from 400 to 800, side scatter from 100 to 300 (Fig. 8). At least 88% of the cells are gated as “live”. Plasmid DNA treated cells are almost identical to untreated cells with the same percentage of cells gated as “live”. PEI/DNA treated cells have slightly lower viable cells (73%) due to toxicity of the PEI. Compared with untreated cells or cells treated with plasmid DNA only, these cells have similar front scattering intensity but slightly larger side scattering intensity. This suggests that after PEI/DNA incubation, the cells maintain their original size but become more granular. After being treated with DNA complexed to POEAmd 1 and PAmd 1, there is a slight decrease in cell viability than PEI, suggesting that the polyamidines are slightly more toxic than PEI under serum-free condition, which differs from the MTT data that were acquired in complete media. The scattering properties of these cells are markedly different than the PEI-treated cells. Here many cells appeared to have shrunk with lower front scattering intensity in the range of 300 to 500. Even more cells have high side-scattering intensity and high granularity. There is no apparent difference between the acid-degradable POEAmd 1 and the non-degradable PAmd 1.

Fig. 8.

Scattering properties of BHK-21 cells exposed to polyplexes transfection for 4 h in serum-free medium, followed by post-transfection incubation for 20 h in 10% serum-containing medium. Dotted circle points to the normal cell population.

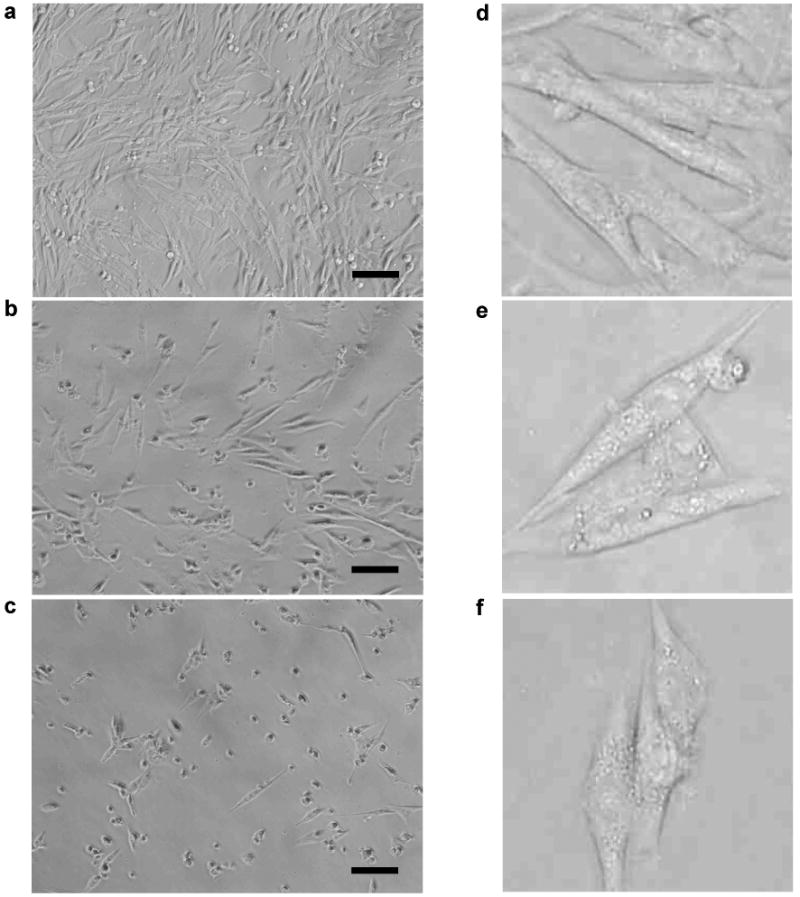

The observations on cell morphology based on light scattering properties were further confirmed by direct visualization of cells using light microscopy. Blank cells cultured on tissue culture plates spread well on the substrate and proliferated (Fig. 9a), whereas cells exposed to PEI polyplexes had a lower cell number and some of the cells appeared rounded and shrunken with more granularity (Fig. 9b). After treatment with POEAmd 1 polyplexes, even more cells had rounded shapes and internal granularity was more pronounced (Fig. 9c). There was no significant difference between cells treated with the acid-labile POEAmd 1 and the non-acid-labile PAmd 1. At higher magnification the untreated blank cells appeared rather smooth (Fig. 9d), yet polyplex-treated cells contained numerous, large vesicular structures in the cytoplasm (Fig. 9e and f).

Fig. 9.

Morphology of BHK-21 cells exposed to polyplex transfection for 4 h in serum-free medium, followed by post-transfection incubation for 20 h in 10% serum-containing medium. Shown are representative bright-field light microscopy images of blank cells (a) and cells treated with PEI polyplexes (b) or POEAmd 1 polyplexes (c). Further magnified images of blank cells (d) and polyplex-treated cells (e) and (f) with higher internal granularity. Scale bar: 100 μm.

These studies show that the polyamidine-based copolymers are able to trigger distinct cellular changes, resulting in smaller overall size and higher granularity. Cationic polymers are known to cause cellular stress and even death via primarily the apoptotic pathway [41,42]. Some cationic polymers are also reported to alter the morphology and light scattering properties of macrophages [43,44]. In the case of the polyamidines and the BHK-21 cells, both acid-labile and non-acid-labile polymer/DNA complexes had similar effects on cell morphology and scattering properties, probably due to their similar positive surface charges with zeta-potential values of 49.95±6.68 mV and 47.04±4.48 mV, respectively. It is possible that these cellular changes are related to cellular stress responses toward highly positively charged colloidal polymer/DNA particles and the initiation of cell death pathways, such as early apoptosis and autophagy, or “self-eating”, a survival mechanism by cells under stress [45]. Autophagy is known to cause shrinkage of cells and the formation of autophagosomes, the large vesicular subcellular organelle and the hallmark of autophagy, which may account for the increase in subcellular granularity. It is also possible that some cells, while still being alive, may have begun the early phase of apoptosis, in response to the polyamidines, which may contribute to changes in decreasing cell size and increasing granularity. While PEI/DNA complexes at the same N:P ratio were also positively charged with a slightly lower zeta-potential (34.45±7.54 mV), the effect on cell viability, size and morphology was not as pronounced as that of the polyamidines (Fig. 9 and 10). Although the cationic nature of all these polymers may play an important role, the exact mechanism appears to be unique to the polyamidines and is not entirely clear at this point. Further clarification and exploitation of these mechanisms may lead to refined polymer carriers that trigger specific responses in target cells.

Fig. 10.

Representative gene transfection of BHK-21 cells. The cells were incubated with the polyplexes of various N:P ratio for 4 h in the absence of serum, and GFP expression was quantified by FACS 20 h later. The GFP positive gate was set based on the transfection results of polyplexes using a luciferase (LUC) plasmid to exclude the influence of cell autofluorescence. The numbers in each panel are the fractions of GFP-positive cells in percentage of the total live cells.

Transfection efficiency of BHK-21 cells was assessed using GFP as the reporter gene. In a typical experiment, transfection by naked GFP plasmid was, as expected, extremely low (∼0.02%), similar to blank cells and cells treated with polyplexes of luciferase plasmid (Fig. 10). On the other hand, transfection with polyplexes composed of 25-kDa branched PEI and GFP plasmid at N:P ratio of 8 resulted in GFP positive cells of almost 16% (Fig. 10). Compared to PEI, the transfection efficiency by the polyamidine/DNA complexes was real yet surprisingly low, ranging from ∼0.1 to 0.2% (Fig. 10). Polyplexes of N:P ratio of 4 and 8 were generally more efficient than N:P ratio of 16.

Key obstacles to nonviral gene transfer have been identified to be cellular uptake, endosomal escape, nuclear translocation, and DNA release from carrier [46]. We have shown that both types of polyamidine described here are capable of binding to and condensing plasmid DNA into nanoparticles of similar size and stability. Therefore, it is reasonable to predict that the polyplexes will be internalized in similar degrees by cells via endocytosis. We have also shown that only the acid-labile poly(ortho ester amidine) but not the non-acid-labile polyamidine is capable of degrading at endosomal pH (∼5) and releasing DNA. Interestingly, however, we did not observe significant difference in gene transfection between the acid-labile and the non-labile polyamidines. There are several possible reasons for this observation. One possibility is that the rate of acid-triggered hydrolysis may not be optimally tuned to cause endosome disruption, and the DNA might have been released too quickly and too early. Another possibility is that unlike the PEI, the chemical structures of the polyamidine and its hydrolytic products might not facilitate direct endosomal escape through the “proton sponge” mechanism. In either case, the consequence would be that the DNA is trapped in the endosome, digested, and deactivated. The results reported here illustrate the importance of optimizing the timing of acid-triggered DNA release and endosomal escape by proper design of the acid-labile chemistry of the polymer carrier. The poly(ortho ester amidine) chemistry is highly versatile, which should allow for further tuning of the acid-labile degradation rate and for incorporating chemical functionalities to promote endosomal escape. The validation of such material designs by subcellular trafficking studies will be the focus of future research.

4. Conclusions

We have demonstrated the synthesis and characterization of a new type of acid-labile poly(ortho ester amidine) copolymers, POEAmd. We showed that structures of POEAmd had a profound impact on the physico-chemical properties of the polyplexes, including nanoparticle size and stability, as well as biological properties such as DNA release, cytotoxicity, and gene transfection. Furthermore, the POEAmd triggered intracellular stress responses that are unique and distinguished from other cationic polymers. Further understanding of the polymer/cell interaction and refining the pH-triggered polymer degradation should lead to more efficient polyamidine-based gene delivery carriers.

Acknowledgments

The financial support to this work is in part by the NIH (Grant R01CA129189, to C. Wang), the NSF CAREER Award (BES 0547613, to C. Wang), the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (No. NCET-10-0435, to R. Tang), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21004030, 50873080, to R. Tang), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province of China (No. BK2010145, to R. Tang), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China (JUSRP21013, to R. Tang).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mintzer MV, Simanek EE. Chem Rev. 2009;109:259–302. doi: 10.1021/cr800409e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Rorke S, Keeney M, Pandit A. Prog Polym Sci. 2010;35:441–458. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeong J, Kim S, Park T. Prog Polym Sci. 2007;32:1239–1274. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niven R, Pearlman R, Wedeking T, Mackeigan J, Noker P, Simpson-Herren L, Smith JG. J Pharm Sci. 1998;87:1292–1299. doi: 10.1021/js980087a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medina-Kauwe LK, Xie J, Hamm-Alvarez S. Gene Ther. 2005;12:1734–1751. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schaffer DV, Fidelman NA, Dan N, Lauffenburger DA. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2000;67:598–606. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(20000305)67:5<598::aid-bit10>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohkuma S, Poole B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:3327–3331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.7.3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kielian MC, Marsh M, Helenius A. EMBO J. 1986;5:3103–3109. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04616.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner E. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 1999;38:279–289. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(99)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Honig D, DeRouchey J, Jungmann R, Koch C, Plank C, Radler JO. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:1802–1809. doi: 10.1021/bm1002569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y, Nguyen J, Steele T, Merkel O, Kissel T. Polymer. 2009;50:3895–3904. [Google Scholar]

- 12.van de Wetering P, Cherng JY, Talsma H, Hennink WE. J Control Release. 1997;49:59–69. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(97)00248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Layman JM, Ramirez SM, Green MD, Long TE. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:1244–1252. doi: 10.1021/bm9000124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Duve C, De Barsy T, Poole B, Trouet A, Tulkens P, Van Hoof F. Biochem Pharmacol. 1974;23:2495–2531. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(74)90174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho YW, Kim JD, Park K. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2003;55:721–734. doi: 10.1211/002235703765951311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang RP, Palumbo RN, Nagarajan L, Krogstad E, Wang C. J Control Release. 2010;142:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brito L, Little S, Langer R, Amiji M. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:1179–1187. doi: 10.1021/bm7011373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green JJ, Zugates GT, Tedford NC, Huang YH, Griffith LG, Lauffenburger DA, Sawicki JA, Langer R, Anderson DG. Adv Mater. 2007;19:2836–2842. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu JS, Li NJ, Xu QF, Ge JF, Lu JM, Xia XW. Polymer. 2010;51:1709–1715. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knorr V, Russ V, Allmendinger L, Ogris M, Wagner E. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:1625–1634. doi: 10.1021/bc8001858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shim MS, Kwon YJ. J Control Release. 2009;133:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shim MS, Kwon YJ. Biomaterials. 2010;31:3404–3413. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boomer JA, Qualls MM, Inerowicz HD, Haynes RH, Patri VS, Kim JM, Thompson DH. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009;20:47–59. doi: 10.1021/bc800239b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu ZH, Gu WW, Chen LL, Gao Y, Zhang ZW, Li YP. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:3119–3126. doi: 10.1021/bm800706f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heller J, Barr J, Ng SY, Abdellauoi KS, Gurny R. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54:1015–1039. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heller J, Barr J. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5:1625–1632. doi: 10.1021/bm040049n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang RP, Palumbo RN, Ji WH, Wang C. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:722–727. doi: 10.1021/bm9000475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang C, Ge Q, Ting D, Nguyen D, Shen HR, Chen JZ, Eisen HN, Heller J, Langer R, Putnam D. Nature Mater. 2004;3:190–196. doi: 10.1038/nmat1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang RP, Ji WH, Wang C. Macromol Biosci. 2010;10:192–201. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200900229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hwang SJ, Bellocq NC, Davis ME. Bioconjugate Chem. 2001;12:280–290. doi: 10.1021/bc0001084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonzalez H, Hwang SJ, Davis ME. Bioconjugate Chem. 1999;10:1068–1074. doi: 10.1021/bc990072j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Savitsky AO, Gasilova ER, Ten'kovtsev AV. Polym Sci Series A. 2009;51:259–268. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petersen H, Kunath K, Martin AL, Stolnik S, Roberts CJ, Davises MC, Kissel T. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3:926–936. doi: 10.1021/bm025539z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mosmann T. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heller J. Adv Polym Sci. 1993;107:41–92. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang X, Du F, Cheng J, Dong Y, Liang D, Ji S, Lin SS, Li Z. Macromolecules. 2009;42:783–790. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang X, Du F, Liang D, Lin SS, Li Z. Macromolecules. 2008;41:5433–5440. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oikawa M, Wada A, Okazaki F, Kusumoto S. J Org Chem. 1996;61:4469–4471. doi: 10.1021/jo960081a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jilek S, Merkle HP, Walter E. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2005;57:377–390. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manolova V, Flace A, Bauer M, Schwarz K, Saudan P, Bachmann MF. J Immunol. 2008;38:1404–1413. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hunter AC. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:1523–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hunter AC, Moghimi SM. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797:1203–1209. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuo JH, Jan MS, Lin YL. J Controlled Release. 2007;120:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuo JH, Chang CH, Lin YL, Wu CJ. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2008;64:307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klionsky DJ. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:931–937. doi: 10.1038/nrm2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pack D, Hoffman AS, Pun S, Stayton PS. Nature Rev Drug Discovery. 2005;4:581–593. doi: 10.1038/nrd1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]