Abstract

The purpose of this research is to explore women's perspectives about reasons why persons might decline HIV testing through drawings and verbal descriptions. We asked 30 participants to draw a person that would NOT get tested for HIV and then explain drawings. Using qualitative content analysis, we extracted seven themes. We found apprehension about knowing the result of a HIV test to be the most commonly identified theme in women's explanations of those who would not get tested. This technique was well received and its use is extended to HIV issues.

This qualitative descriptive study was performed as part of the formative stages of a larger ongoing study whose purpose is to develop and test clinical interventions to influence US minority and low income women's acceptance of point of care human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing. In this phase, interviews and drawings were used to elucidate women's views about why individuals might decline HIV testing and to explore whether these views varied for women of different racial and ethnic backgrounds. This approach was used to address the question: What are low income minority women's views about why individuals decline HIV testing?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that more than one million Americans are living with HIV but approximately one-quarter are unaware of their infection. Among US women, ethnic and racial minorities bear a disproportionate burden of HIV with African American women making up 66% of acquired immunodeficiency disease (AIDS) cases in 2006. Many of the women with AIDS have low incomes. Unlike men, women of color are most likely to be infected through heterosexual sex (CDC, 2008) and may be unaware of their risk. In 2006, testing recommendations were modified to improve screening and diagnosis of HIV (CDC, 2006). The current standard of care is for all patients between the ages of 13 and 64 in all health care settings to be offered testing. Therefore, it is up to the patient to decline or opt-out of the procedure. This is often referred to as point of care HIV testing and, when coupled with newer rapid testing methods, it is intended to lead to early treatment and a subsequent decrease in HIV transmission.

HIV is a leading cause of death among non-Hispanic Black women aged 20 to 54 years (Heron &, Tejada-Vera, 2009). Further, HIV screening rates among women and racial and ethnic minorities are lower than optimal (Ostermann, Kumar, Pence & Whetten, 2007). With the advent of more proactive approaches to testing, clinicians will have more opportunities to discuss HIV testing with women who traditionally have not been considered to be at high risk. However, an offer of testing does not guarantee acceptance. Adam and de Wit (2006) concluded in their recent comprehensive literature review of HIV testing barriers that there are two chief personal reasons for individuals to forgo testing. First, they do not see themselves at risk for HIV infection and second, they fear a positive test result. Most of the studies included in this review were conducted with unique populations, such as men who have sex with men, women receiving prenatal care, intravenous drug users, and patients visiting sexually transmitted disease clinics. The views of non-expectant, low income US women presenting for routine primary care are less well documented. Additional understanding of this population's personal attitudes and world views is needed to craft relevant, helpful approaches to clinical communication.

Methods

Drawing as Data

Drawing as a projective technique has been used by several disciplines to expose motivations and perceptions about an object, situation, or condition. Psychologists have used the method in the course of clinical practice as have marketing researchers in investigating how consumers perceive situations, products, and services (McDaniel & Gates, 1997; Ramsey, Ibbotson & McCole, 2006). In health-related research, asking respondents to draw how they perceive and experience their and others' illnesses has been a useful approach to understand various aspects of adults' and children's representations of medical conditions. Guillaume (2004) used drawings to document the impact of heart disease on women's daily functioning. Changes in the size of patients' drawings of their hearts following myocardial infarctions were found to serve as markers of functional outcomes such as cardiac anxiety and exercise/activity restrictions (Broadbent, 2006; Reynolds, Broadbent, Ellis, Gamble, & Petrie, 2007). Taylor (2008) proposed that links between qualitative aspects of cardiac drawings and patients' functional status and recovery over time may explained by drawings tapping into patients' psychological distress.

Other recent examples of studies that used drawings as data to reveal views and experiences with health-related conditions include reports of university students' and children's perceptions of their headaches (Broadbent, Niederhoffer, Hague, Corter, & Reynolds, 2009; Wojaczyriska-Stanek, Koprowski, Wrobel, & Gola, 2008), patients' perceptions of living with systemic lupus erythematosus (Nowicka-Sauer, 2007), women's portrayals of the physical changes accompanying menopause (Guillemin, 2004), and overweight children's perceptions of physical activity (Walker, Caine-Bish & Wait, 2009). This method has also been employed to document respondents' attitudes and understanding about communicable diseases. Gonzales-Rivera and Bauermeister (2007) used drawings to assess Puerto Rican children's attitudes toward persons with AIDS; Locsin, Barnard, Matua, and Bongomin (2003) employed illustrations to obtain insight into Ebola survivors' experiences; and DeAngelo (2000, 2001) elicited drawings of viruses from university students and used them in her subsequent study of threat and stigma associated with microorganisms and contagion.

Many of the aforementioned researchers suggest that respondents' productions of visual representations provide a window into themes that are not easily or comfortably expressed through words. Additionally, data from drawings are purported to be valuable in helping clinicians better understand the context of patients' experiences and to be useful in the formative stages of a study by contributing to instrument development and hypothesis generation. We used patient drawings as an approach in this preliminary study because they were easy to obtain, did not require high literacy, and had good potential to prompt respondents to share attitudes, understandings, and inner emotional states about what they saw as reasons for declining HIV testing.

Setting and Participants

In this qualitative descriptive study (Sandelowski, 2000) drawings were used to elicit women's views about reasons for declining HIV testing. The participants for this study consisted of 30 women recruited in 2007 from three full-service health clinics. The clinics, which documented approximately 3,300 annual visits by women, were managed by the same university-based group and were located in low-income neighborhoods of a Midwestern city with a population of approximately 800,000. To ensure ethnic and racial diversity in the sample, we purposely sampled 10 women from each of the city's three major racial/ethnic groups (non-Hispanic White, African American, and Hispanic or Latino). Non-pregnant women were approached as they waited to be seen for primary care services and were invited to participate in a semi-structured individual interview. The study was approved by the university's institutional review board and written informed consent was obtained from each participant. As compensation for study involvement, each woman was given a retail store gift card valued at $25.

Procedure

Three female research assistants used a semi-structured interview guide to perform the interviews. The interviews, which were held in a private section of each clinic, were digitally recorded. For participants who preferred to communicate in Spanish, bilingual assistants did so using a Spanish version of the guide that had been back-translated for validity. Average time for interview completion was approximately 30 minutes. Following the interviews, research assistants transcribed their own recorded interviews and produced electronic files of the responses and drawings for use in data analysis. At the start of the study, a small set of each assistant's transcripts was checked against the audiotapes and found to be accurate.

The portion of the interview guide that invited the women to draw was preceded by a set of questions designed to elicit their knowledge about HIV/AIDS and reasons they thought individuals like them might decline HIV/AIDS testing. Participants were asked to close their eyes and think about a person who would not get tested for HIV and then a person who would get tested for HIV. Next, participants were given the following instructions:

I have a sheet of paper here, divided into two sections. In the top part of the page, I would like for you to draw the type of person that would NOT get tested for HIV. In the bottom half of the page, I would like you to draw the type of person that WOULD get tested for HIV. I will give you a few minutes to do this. Don't worry about your artistic skills, but do your best to represent this person as you picture them in your head.

Throughout the interviews each assistant used probes and prompts to elucidate and/or augment responses to the questions and to obtain explanations of the drawings. All of the women were asked the same questions in the same order. Clinicians and researchers with expertise in HIV testing gave input into the development of the interview guide. This paper focuses primarily on women's thoughts on why people might not get tested.

Analysis

In analyzing the data we used a multi-pronged investigatory approach that melded visual and word-based methodologies (Guillemin, 2004). In our study, the process of drawing was accompanied by each woman interpreting the drawing, which led her to reflect upon her view of persons who would decline HIV testing. This meaning-making process presumably resulted in an image representation of respondents' current understanding of the phenomenon.

Qualitative content analysis of the data was independently performed by three of the investigators (LS, JR, & RM) who were blind to the demographic characteristics of the participants. The data included the interview transcripts and the drawings. However, we did not attempt to interpret the drawings but rather examined the participants' descriptions of them as part of our thematic content analysis. The group then met together eight times to identify themes and descriptions through iterative analysis and discussion. A theme was designated as such when its elements were reflected by more than one woman. In many of the responses more than one theme was identified. Once the major themes were identified and agreed upon, each of the three researchers was assigned to write descriptions of one or more of the themes and to select representative drawings and quotes for this paper. The three achieved complete agreement on the meaning of each theme, its fidelity to the participants' words and images, and frequency of occurrence (Sandelowski, 2001).

Results

The Interviewees and Process

A total of 30 adult women completed the interviews. Ten identified themselves as Hispanic or Latina, 10 as non-Latina White, and 10 as non-Latina Black or African American. The group ranged in age from 20 to 67 years, with a mean age of 33 years. The large majority (24 of 30) had attained at least a high school education and a few (4 of 30) reported having graduated from college. Many of the women (18 of 30) were married or were in an existing intimate relationship. Seven reported a prior sexually transmitted infection but only three of these women had current partners. From self report, 20 had undergone previous HIV testing; two were uncertain as to whether they had received prior HIV testing; and eight said they had never been tested.

Most of the participants readily complied with the drawing request. However, a few (5 of 30) asked for clarification or feedback from the interviewer, such as, Just a face? and How can you draw a worried person? A sizeable subgroup (13 of 30) made one or more self-derogatory comments about their drawing abilities. One declined to draw but described her mental visualization of a non-tester to the interviewer. A few narrated their drawings with comments made during the process such as, No idea how to make a bright picture, and I have a black pen so I have to use some imagination, alright?

Themes

From the transcribed narratives of women's descriptions of a typical person who declines HIV testing, seven themes were identified. Table 1 lists those themes and the number of participants in each ethnic/racial group whose responses reflected each theme.

Table 1. Themes in Women's Reasons for People Not Getting Tested for HIV by Race/Ethnicity of Participant.

| Theme | Women's Race/Ethnicity | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | Latina | African-American | |

| Apprehension about test results | 10 | 10 | 4 |

| Risk behavior/Negative psychological state | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Low risk perception/Healthy | 3 | 4 | 0 |

| Ill appearance | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Stigma | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Demographic factors | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Low information about HIV testing | 1 | 4 | 1 |

Test Results

Apprehension about the potentially negative outcome or the result of an HIV test was the most prevalent theme identified in women's reasons for individuals not undergoing HIV testing. Included under the theme Test Results were responses that indicated persons refused testing because they do not want to be informed of their HIV status. Many respondents associated negative feelings, especially fear and anxiety, with knowing the results. All of the Latina and White women referred to apprehension about test results as a deterrent to HIV testing. Many of these women's drawings depicted persons with frowns on their faces and almost all used the words, afraid, fear, or scared when discussing this topic. For example, a 26-year-old Latina participant commented;

I think that when a person is afraid, he doesn't want to be tested. I don't know. He hides something like he is afraid of knowing the results. I had an aunt that was very promiscuous person and she was afraid to be tested. She doesn't know and she is not interested [in knowing]. BP01

One White participant also used the term bother and one African American used the term stress when explaining that apprehension about test results may discourage individuals from testing. Three other African American women asserted that they thought that a deterrent to testing was simply the test results. The drawing in Figure 1 is one example of the theme Test Results.

FIGURE 1.

A 24-year-old White woman's drawing. She explained she sees persons who decline HIV testing as “scared” and “in the dark.” (EQ07)

Risk Behavior/Negative Psychological State

The second most prevalent theme was labeled Risk Behavior/Negative Psychological State. Included in this theme were women's comments and drawings that depicted decliners as persons who engaged in high risk behaviors such as excessive drug and alcohol use and unsafe sexual practices. In several cases these risky activities were linked with descriptions of individuals having a negative mood or despondent state of mind that contributed to their not accepting testing despite being at risk for HIV. One 29-year-old African American elaborated on her drawing thusly:

He's got a frown on his face, he's sad, he doesn't have any clothes on… he's got things lacking in his life…he's got things going on in his life which cause him to make bad decisions and thing escalate from there. When you're happy you don't tend to make as many wrong decisions as you would be if you were in an unhappy mind state because normally it's self-destruction. And a person doing things they shouldn't be doing and they're not getting tested and they're not taking care of themselves, you have to be unhappy. There's just nothing – no rhyme or reason why you wouldn't take care of yourself if you valued yourself. (RB02)

As another example, a 27-year-old White respondent said,

Looks like somebody that does drugs and alcohol, smokes and just living the wrong kind of lifestyle. (EQ04)

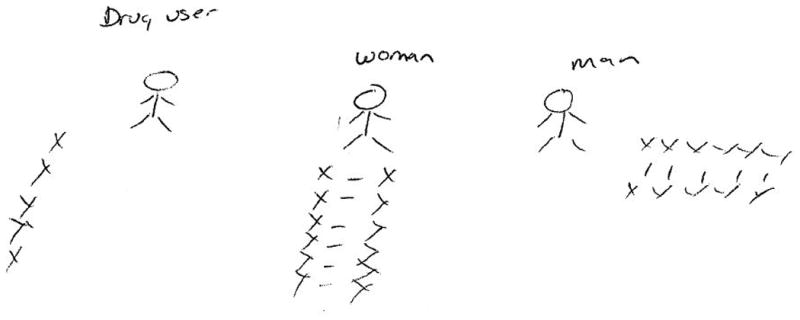

To some extent, fewer White women referenced risk behavior and negative affect (2 of 10) compared to African American and Latina women (10 of 20). Among women of color, unsafe sexual practice was the most common specific risk behavior mentioned. The drawing in Figure 2 is one participant's view of non-testers who engage in risk behavior.

FIGURE 2.

This 31-year-old African American woman's drawing shows X's around non-testers (drug users and sexually promiscuous men and women) that to her represent the spread of HIV through sexual partners and needle sharing. (RB03)

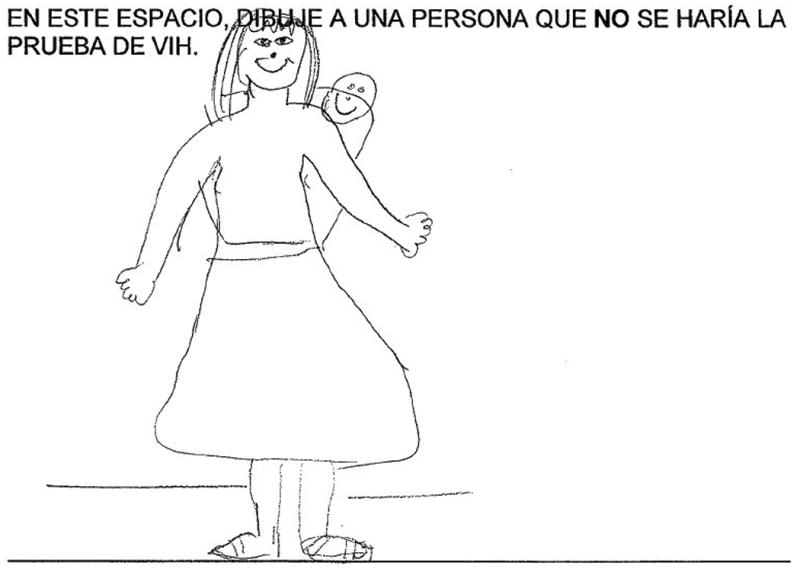

Low Risk Perception/Healthy

The remaining five themes were essentially equivalent in terms of their occurrence. In contrast to the theme of risk behavior was the theme Low Risk Perception/Healthy. Important features of this theme were women's references to decliners thinking they did not need the test because of low or no possibility of having the infection. Women drew and described these people as declining testing because they considered themselves healthy and/or with no exposure to HIV. Figure 3 shows an older participant's drawing of her view of a young decliner. A 26-year-old Latina explained her drawing as follows;

FIGURE 3.

A 55-year-old White participant's drawing of a non-tester with stylish baggy clothes who she said is “young” and will not get tested because he thinks he's “cool” and “immortal.” (EQ03)

Healthy. I drew the woman, as I told you before, she is happy, doesn't know and she is not interested. She looks healthy and she thinks she is healthy. BP01

Another 31-year-old Latina commented,

They may say if I have a husband, I don't need to get tested. BP06

Ill Appearance

In contrast to appearing healthy, individuals whose bodily appearances indicated they were physically sick and possibly suffering from AIDS was another theme identified from women's depictions of non-testers. Ill Appearance equated looking sickly with being ill, explicitly or implicitly from AIDS. References were made to low weight, vomiting, and unhealthy facial characteristics. A 52-year-old White participant made the following comment.

This one would be throwing up…because what I see on TV and hear, they do get sick and get skinny and everything. EQ06

Two White women and two African American women provided Ill Appearance explanations. This theme was not identified in any of the Latinas' responses.

Stigma

Central aspects of the theme Stigma were drawings and explanations for declining testing that made reference to others' negative opinions and loss of respect associated with the act of HIV testing. One 46-year-old White woman expressed her view of non-testers' rationale by explaining,

It's like ‘oh, well no,’ cuz people label me as a slut or a, you know, or a pothead or a dopehead or anything of that. EQ09

In explaining her drawing, another 34-year-old Latina commented,

They feel embarrassed about staying on the line waiting to do the HIV test. BP07

A 33-year-old African American's drawing of a man in a suit was accompanied by this explanation:

This drawing is President Bush. Because the reason why I feel that he wouldn't get tested is because of what the population of American would think of him. He is, you know, the so called leader of the United States. The President of the United States he wants to portray that leadership as being a leader and doing positive things. But if he is known to have HIV test even AIDS, he'll just lose all respect. People would lose all respect for him, more or less. Umm, because he wants to have people looking at him as being a perfect person. RB10

Demographic Factors

Some of the women referenced Demographic Factors when they spoke and drew about this issue. This theme included categorizing individuals who decline HIV testing on the basis of their socioeconomic status, education level, gender, place of residence, and age. These comments were mostly global generalizations. Males were portrayed as less likely to be tested than females in two cases and females less likely in one. Two interviewees described younger persons as less likely than older persons to be tested but no specifics about age were provided. Higher economic status leading to fear of stigma was given as an obstacle to testing but no details about status were included. Here are three representative quotes.

I just think women are sometimes not as willing sometimes to get some type of information like that [test results] that would bother them. (25- year-old White respondent) EQ01

I think upper class or somebody more wealthy would be afraid to [test] because of how they would be portrayed, how they would be looked at. (28-year-old White respondent) EQ05

This one here represents one person like the people from the mountains in my country. They are not educated and have many kids and definitely they have had a hard life and they are not informed about what is HIV neither about the consequences. (20-year-old Latina interviewee) BP09

The drawing made by the respondent who offered this third explanation is shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

A Latina's picture depicts a non-tester as an émigré from a rural area and poorly informed about HIV. (BP09)

Low Information

The final theme we identified was Low Information. This theme included responses and drawings that indicated there was either a lack of information or misinformation regarding HIV/AIDS and HIV testing. Relatively more Latina participants (4) than African American (1) or white (1) cited Low Information as a possible barrier to testing. Three of the respondent's drawings that displayed this theme did so by contrasting images of non-testers with testers. One 29- year-old African-American explained her drawings of an unclothed non-tester and a fully clothed tester by describing the non-tester as follows:

He's naked on information; unaware, vulnerable. RB02

Two participants drew images of testers with books or reading material in their hands, which they said depicted knowledge or information, and non-testers with empty hands, which showed lack of information. Their explanations are given below.

A person who wouldn't test would know more of…what you hear on the streets about it, but not medically what you would hear. (32-year-old White participant) EQ10

This is someone who is ignorant about that issue. (20-year-old Latina) BP07

Discussion

Because HIV testing is a sensitive, personal subject and one about which individuals may often give socially acceptable answers, we used a projective technique to explore what women thought were likely reasons for individuals not engaging in testing. Overall, the procedure was well received, with most of those initially hesitant to cooperate given enough reassurance to complete the task. Our data were derived from structured elicitation interviews that included women's drawings. These interviews were part of the formative stages of a larger study of women's knowledge and attitudes about HIV testing and they were performed in urban primary care clinics. The sample was designed to include women from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds in order to discern possible differences in attitudes based on cultural background.

From previous researchers' findings on individuals' views about HIV testing, there appear to be two chief reasons for refusal to be tested. The first is that people decline testing because they fear a positive test result and second because they do not perceive the need (e.g., do not consider themselves at risk for HIV infection) (Adam & De Wit, 2006). In accord with earlier findings, we found the theme of anxiety or fear of test results featured prominently in women's responses regardless of their racial or ethnic group membership. The entire sample of White and Latina women gave explanations that included concern about learning test results as a reason for not being tested. African American women also referenced this reason but to a lesser extent. Also, a few of the women said some decliners just prefer not to know their test results and provided no explanation of reasons. Most women's responses reflected several themes about the characteristics of non-testers and we did not ask the respondents to elaborate on which ones were the most salient. However, based on the number of women who mentioned apprehension about the results of HIV testing (presumably a positive result) in their discussion of non-testers, we concluded that, in this sample's view regardless of race or ethnicity, this was most important reason for people not testing for HIV.

Several other authors have recently examined this issue among persons seeking services at primary and urgent care facilities and have found perception of low personal risk to be a predominant reason that US patients offer for not being interested in and/or declining HIV testing (Akers, Bernstein, Henderson, Doyle, & Corbie-Smith, 2007; Brown, et al, 2008; Cunningham, et al, 2009; Liddicoat, Losina, Kang, Freedberg, & Walensky 2006; Weis, et al, 2009). Though this was a theme we detected among the reasons women gave for people not accepting testing, it was expressed by only a small proportion of the sample. And, unexpectedly, perception of low risk was an explanation that was not articulated in any of the responses given by the African American participants. This finding may very well be due to the uniqueness of our sample. Nine of the 10 African American women gave a history of previous HIV testing, compared with only 11 of the 20 others. Our results may also reflect a greater acknowledgement of the risk of HIV infection by African Americans in general compared to Latinos and Whites. According to the 2009 Survey of Americans on HIV/AIDS (Kaiser Family Foundation), 73% of non-elderly African-Americans reported that they had been tested at some point for HIV compared with 60% of Latinos and 48% Whites. Also, from this same survey, 38% of African American respondents indicated they were personally very concerned about becoming infected with HIV as compared with 26% of Latinos and 6% of Whites (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2009).

For the remaining themes there were minimal differences in perceptions based on race or ethnicity of the participants. To a lesser extent we found that non-testers were viewed by these women as people who often engaged in health-harming or high risk behaviors, some with accompanying negative psychological states. Women also depicted non-testers as people who were ill-appearing due to AIDS. Stigma associated with HIV testing was directly referenced by only a few women we interviewed. Although some respondents emphasized demographic characteristics of non-testers, these factors were quite varied. Lastly some women saw non-testers as persons who were ill-informed about HIV testing.

Implications and Limitations

The latest US policy changes are designed to make HIV testing a more routine and normalized behavior in clinical settings; however, inevitably some patients will hesitate or balk at having the procedure. Brief clinical interventions informed by patients' perspectives could increase acceptance of testing. Although to some extent our findings parallel those of previous studies, this description augmented by drawings provides a window into how women conceptualized and visualized persons' reasons for declining testing. These images could be useful to clinicians who conduct behavioral counseling sessions in which objections to testing are discussed.

As a preliminary study our sample was small and restricted to women seeking care at geographically similar community health clinics. As a group these women were favorably inclined toward universal HIV testing (Burrage, et al, 2008). Further, this study was not based on respondents' self-examination of their personal motives for forgoing HIV testing but rather on their estimate or judgment about others' reasons for not testing. Thus, no conclusions can be drawn about actual barriers to HIV testing. However, our study does illustrate how a projective technique such as drawing can be used to elucidate what a community of women perceives as important forces underlying non-testing behavior. Future research that documents women's actual testing behavior and compares their personal reasons for testing and not testing is needed for enhanced understanding of contemporary HIV testing issues.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the National Institute of Nursing Research (R01 NR010004 – Zimet, PI).

Contributor Information

Rose M. Mays, Department of Family Health, Indiana University School of Nursing, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA

Lynne A. Sturm, Riley Child Development Center, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis Indiana, USA

Julie C. Rasche, Indiana University School of Nursing, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA

Dena S. Cox, Indiana University Kelley School of Business, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA

Anthony D. Cox, Indiana University Kelley School of Business, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA

Gregory D. Zimet, Department of Pediatrics, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indiana, USA

References

- Adam PCG, de Wit JBF. A concise overview of barriers and facilitators to HIV testing: Directions for future research and interventions. Utrecht, the Netherlands: Institute for Prevention and Social Research; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Akers A, Bernstein L, Henderson S, Doyle J, Corbie-Smith G. Factors associated with lack of interest in HIV testing in older at-risk women. Journal of Women's Health. 2007;16(6):842–858. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent E, Ellis CJ, Gamble G, Petrie KJ. Changes in patient drawings of the heart identify slow recovery after myocardial infarction. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;68:910–913. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000242121.02571.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent E, Niederhoffer K, Hague T, Corter A, Reynolds L. Headache sufferers' drawings reflect distress, disability and illness perceptions. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2009;66:465–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Kuo I, Bellows J, Barry R, Bui P, Wohlegemuth J, Wills E, Parikh N. Patient perceptions and acceptance of routine emergency department HIV testing. Public Health Reports. 2008;123(Supplement 3):21–26. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrage JW, Zimet GD, Cox DS, Cox AD, Mays RM, Fife RS, Fife KS. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention revised recommendations for HIV testing: Reactions of women attending community health clinics. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2008;19(1):66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2006;55:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Subpopulation Estimates from the HIV Incidence Surveillance System – United States, 2006. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008;57(6):1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CO, Doran B, DeLuca J, Dyksterhouse R, Asgar R, Sacajiu G. Routine opt-out HIV testing in an urban community health center. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2009;23(8):619–623. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelo L. Stereotypes and stigma: Biased attributions in matching older persons with drawings of viruses? International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2000;51(2):143–154. doi: 10.2190/Q863-DAQ7-HK8V-EAG3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelo L. Subliminal perception: Biased attributions in matching persons with drawings of germs? Journal of Health Psychology. 2001;6(4):457–466. doi: 10.1177/135910530100600408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales-Rivera M, Bauermeister JA. Children's attitudes toward people with AIDS in Puerto Rico: Exploring stigma through drawings and stories. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17(2):250–263. doi: 10.1177/1049732306297758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemin M. Understanding illness: Using drawings as a research method. Qualitative Health Research. 2004a;14(2):272–289. doi: 10.1177/1049732303260445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemin M. Embodying heart disease through drawings. Health. 2004b;8(2):223–239. doi: 10.1177/1363459304041071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron MP, Tejada-Vera B. National Vital Statistics Reports. 8. Vol. 58. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2009. Deaths: Leading causes for 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation 2009 Survey of Americans on HIV/AIDS: Summary of Findings on the Domestic Epidemic. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/upload/7889.pdf.

- Liddicoat R, Losina E, Kang M, Freedberg KA, Walensky RP. Refusing HIV testing in an urgent care setting: results from the “Think HIV” program. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2006;20(2):84–92. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locsin RC, Barnard A, Matua AG, Bongomin B. Surviving Ebola: Understanding experience through artistic expression. International Nursing Review. 2003;50:156–166. doi: 10.1046/j.1466-7657.2003.00194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel CD, Gates RH. Marketing Research Essentials. 2nd. South-Western College Publishing; Cincinnati, OH: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nowicka-Sauer K. Patients' perspective: Lupus in patients' drawings. Clinical Rheumatology. 2007;26:1523–1525. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0619-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostermann J, Virender K, Pense BW, Whetten K. Trends in HIV testing and differences between planned and actual testing in the United States, 2000-2005. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167(19):2128–2135. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey E, Ibbotson P, McCole P. Application of projective techniques in an e-business research context: a response to ‘Projective techniques in market research - valueless subjectivity or insightful reality? International Journal of Market Research. 2006;48(5):551–573. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds L, Broadbent E, Ellis C, Gamble G, Petrie KJ. Patients' drawings illustrate psychological and functional status in heart failure. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2007;63:525–532. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski Real qualitative researchers do not count: The use of numbers in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health. 2001;24:230–240. doi: 10.1002/nur.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE. Current issues and new directions in Psychology and Health: Bringing basic and applied research together to address underlying mechanisms. Psychology & Health. 2008;23:131–134. doi: 10.1080/08870440701747477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker K, Caine-Bish N, Wait S. “I like to jump on my trampoline”: An analysis of drawings from 8-to 12-year-old children beginning a weight-management program. Qualitative Health Research. 2009;19(7):907–917. doi: 10.1177/1049732309338404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis KE, Liese AD, Hussey J, Coleman J, Powell P, Gibson JJ, Duffus WA. A routine HIV screening program in a South Carolina community health center in an area of low HIV prevalence. AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2009;23(4):251–258. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojaczyriska-Stanek K, Koprowski R, Wrobel Z, Gola M. Headache in childrens' drawings. Journal of Child Neurology. 2008;23(2):184–191. doi: 10.1177/0883073807307985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]