Summary

The Twist1 transcription factor is known to promote tumor metastasis and induce Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT). Here, we report that Twist1 is capable of promoting the formation of invadopodia, specialized membrane protrusions for extracellular matrix degradation. Twist1 induces PDGFRα expression, which in turn activates Src, to promote invadopodia formation. We show that Twist1 and PDGFRα are central mediators of invadopodia formation in response to various EMT-inducing signals. Induction of PDGFRα and invadopodia is essential for Twist1 to promote tumor metastasis. Consistent with PDGFRα being a direct transcriptional target of Twist1, coexpression of Twist1 and PDGFRα predicts poor survival in breast tumor patients. Therefore, invadopodia-mediated matrix degradation is a key function of Twist1 in promoting tumor metastasis.

Introduction

During metastasis, carcinoma cells acquire the ability to invade surrounding tissues and intravasate through the endothelium to enter systemic circulation. Both the invasion and intravasation processes require degradation of basement membrane and extracellular matrix (ECM). Although proteolytic activity is associated with increased metastasis and poor clinical outcome, the molecular triggers for matrix degradation in tumor cells are largely unknown.

Invadopodia are specialized actin-based membrane protrusions found in cancer cells that degrade ECM via localization of proteases (Tarone et al., 1985, Chen, 1989). Their ability to mediate focal ECM degradation suggests a critical role for invadopodia in tumor invasion and metastasis. However, a definitive role for invadopodia in local invasion and metastasis in vivo has not yet been clearly demonstrated. As actin-based structures, invadopodia contain a primarily branched F-actin core and actin regulatory proteins, such as cortactin, WASp, and the Arp2/3 complex (Linder, 2007). The SH3-domain-rich proteins Tks4 (Buschman et al., 2009) and Tks5 (Seals et al., 2005) function as essential adaptor proteins in clustering structural and enzymatic components of invadopodia. The matrix degradation activity of invadopodia has been associated with a large number of proteases, including membrane type MMPs (MT1-MMP) (Linder 2007). Invadopodia formation requires tyrosine phosphorylation of several invadopodia components including cortactin (Ayala et al., 2008), Tks4 (Buschmann et al., 2009), and Tks5 (Seals et al., 2005) by Src family kinases.

Our previous study found that the Twist1 transcription factor, a key regulator of early embryonic morphogenesis, was essential for the ability of tumor cells to metastasize from the mammary gland to the lung in a mouse breast tumor model and was highly expressed in invasive human lobular breast cancer (Yang et al., 2004). Since then, studies have also associated Twist1 expression with many aggressive human cancers, such as melanomas, neuroblastomas, prostate cancers, and gastric cancers (Peinado et al., 2007). Twist1 can activate a latent developmental program termed the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), thus enabling carcinoma cells to dissociate from each other and migrate.

The EMT program is a highly conserved developmental program that promotes epithelial cell dissociation and migration to different sites during embryogenesis. During EMT, cells lose their epithelial characteristics, including cell adhesion and polarity, and acquire a mesenchymal morphology and the ability to migrate (Hay, 1995). Biochemically, cells downregulate epithelial markers such as adherens junction proteins E-cadherin and catenins and express mesenchymal markers including vimentin and fibronectin (Boyer and Thiery, 1993). In addition to Twist1, the zinc-finger transcription factors, including Snail, Slug, ZEB1, and ZEB2 (Peinado et al., 2007), can also activate the EMT program by directly binding the E-boxes of the E-cadherin promoter to suppress its transcription. However, it is unclear how Twist1, as a bHLH transcription factor, controls the EMT program. In this study, we test the hypothesis that Twist1 plays a major role in regulating ECM degradation to promote tumor metastasis.

Results

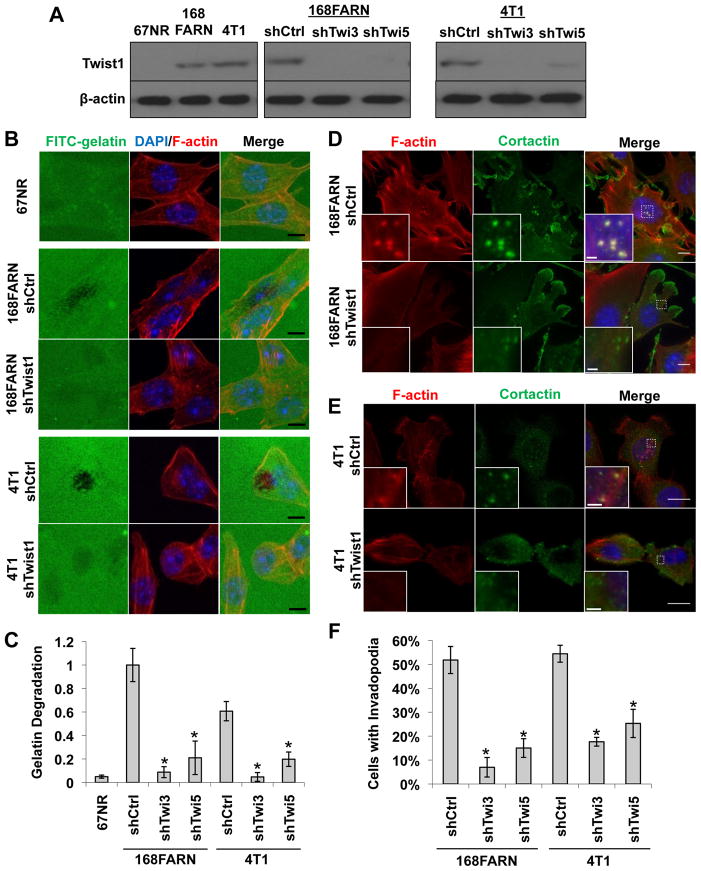

Twist1 is necessary and sufficient for invadopodia formation and function

Our previous studies found that Twist1 expression was associated with increased metastatic potentials in a series of mouse mammary tumor cell lines, including 67NR, 168FARN, and 4T1 (Yang et al., 2004). Furthermore, Twist1 is required for the ability of 4T1 cells to metastasize from the mammary gland to the lung. To dissect the cellular functions of Twist1 in promoting tumor metastasis, we first tested whether expression of Twist1 was associated with increased ability to degrade ECM. 67NR, 168FARN, and 4T1 cells were plated onto FITC-conjugated gelatin matrix to assess their abilities to degrade matrix. We found that Twist1-expressing metastatic 168FARN and 4T1 cells potently degraded ECM in eight hours, while non-metastatic 67NR cells that do not express Twist1 failed to do so (Figure 1A–C). To test whether Twist1 is required for the ability of 168FARN and 4T1 cells to degrade ECM, 168FARN and 4T1 cells expressing two independent shRNAs against Twist1 were processed for the matrix degradation assay (Figure 1A). Indeed, we found that suppressing Twist1 expression resulted in a potent reduction in matrix degradation in both cell types (Figure 1B–C). Together, these results demonstrate that Twist1 is required for ECM degradation ability in tumor cells.

Figure 1. Twist1 is necessary for invadopodia formation.

A. Indicated cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and probed for Twist1 and β-actin.

B. 67NR, 168FARN (expressing control or Twist1 knockdown shRNA), and 4T1 (expressing control or Twist1 knockdown shRNA) cells were plated on FITC-conjugated gelatin (green) for 8 hours. F-actin was stained with phallodin (red) and nuclei with DAPI (blue). Areas of gelatin degradation appear as punctuate black areas beneath the cells.

C. Quantification of FITC-gelatin degradation. N=150 cells/sample. *p<0.02.

D–E. 168FARN and 4T1 cells expressing control or Twist1 shRNAs were stained with phalloidin (red), DAPI (blue), and cortactin (green).

F. Quantification of percentage of cells with invadopodia. N=150 cells/sample. *p<0.02.

Error bars are standard error of mean (SEM). Scale bars are 1 μm for insets, 5 μm for full images.

See also Figure S1.

Localized matrix degradation can be mediated through actin-based subcellular protrusions called invadopodia. Colocalization of F-actin with the actin-bundling protein cortactin (Bowden et al., 2006) or the unique adaptor protein Tks5 (Abram et al., 2003) can be used to identify invadopodia. To determine whether invadopodia are present in 168FARN and 4T1 cells and whether Twist1 is required for invadopodia formation, we examined the presence of invadopodia in 168FARN and 4T1 cells by immunofluorescence. Invadopodia are transient structures, so only a fraction of cells possess invadopodia at any given time. Indeed, over 50% 168FARN and 4T1 cells contain invadopodia, while suppression of Twist1 expression reduced the occurrence of invadopodia to 5–20% in both cell lines (Figure 1D–1F, S1A, and S1B). These data indicate that Twist1 is necessary for the formation of invadopodia for ECM degradation.

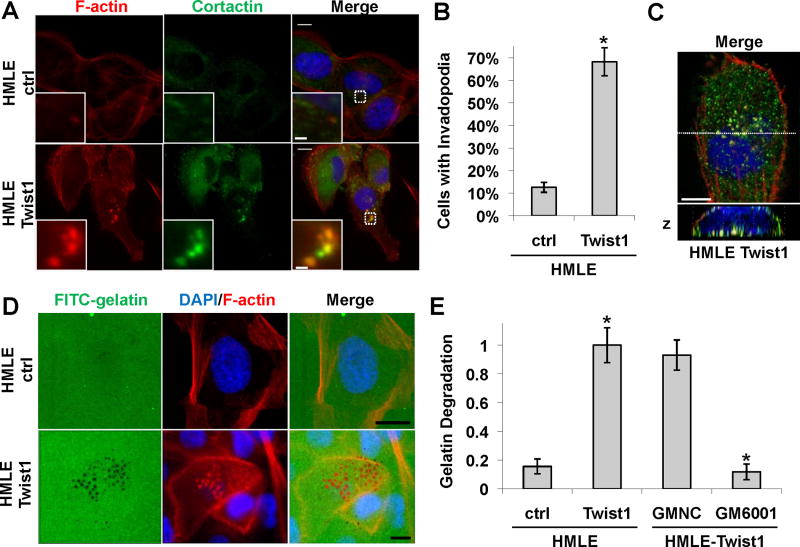

Since 168FARN and 4T1 mouse tumor cells contain additional genetic and epigenetic changes essential for their tumorigenic and metastatic abilities (Mani et al., 2007), we next tested whether Twist1 is sufficient to promote invadopodia formation and matrix degradation in HMLE cells, immortalized normal human mammary epithelial cells. As reported, expression of Twist1 induced EMT in HMLE cells (Yang et al., 2004). We examined the presence of invadopodia and found that over 60% of HMLE cells expressing Twist1 contained invadopodia, compared to 10% of HMLE control cells with invadopodia (Figure 2A, 2B, and S2A). Importantly, these invadopodia were all localized to the basal surface of the cell directly adjacent to the underlying matrix when examined with Z-sectioning (Figure 2C). To determine whether these Twist1-induced invadopodia are functional, we compared the ability of these two cell lines to degrade matrix using the FITC-gelatin degradation assay. Expression of Twist1 increased matrix degradation by approximately 10 fold (Figure 2D and 2E). Strikingly, focal matrix degradation precisely colocalized with F-actin positive puncta (Figure 2D), indicating that Twist1 is sufficient to promote the formation of functional invadopodia in HMLE cells. Furthermore, Twist1-induced matrix degradation is protease-driven since suppression of metalloproteases by GM6001 inhibited the ability of HMLE-Twist1 cells to degrade FITC-gelatin (Figure 2E). Together, these data demonstrate that Twist1 is both necessary and sufficient to promote invadopodia formation and focal matrix degradation.

Figure 2. Twist1 is sufficient to promote invadopodia formation.

A. HMLE cells expressing a control vector or Twist1 were plated on 0.2% gelatin matrix for 72 hours and invadopodia were visualized by colocalization of cortactin (green) and F-actin (red).

B. Quantification of cells with invadopodia. N=150 cells/sample. *p<0.02.

C. Colocalization of F-actin (red) and cortactin (green) is restricted to the basal side of cells in direct contact with the underlying matrix.

D. HMLE control or HMLE-Twist1 cells were plated on FITC-gelatin for 8 hours and stained for F-actin (red) and nuclei (blue).

E. Quantification of degradation by HMLE-ctrl and HMLE-Twist1 cells and HMLE-Twist1 cells treated with 25 μM GM6001 Negative Control (GMNC) or 25 μM GM6001 for eight hours. N=150 cells/sample. *p<0.02.

Error bars are SEM. Scale bars are 1 μm for insets, 5 μm for full images.

See also Figure S2.

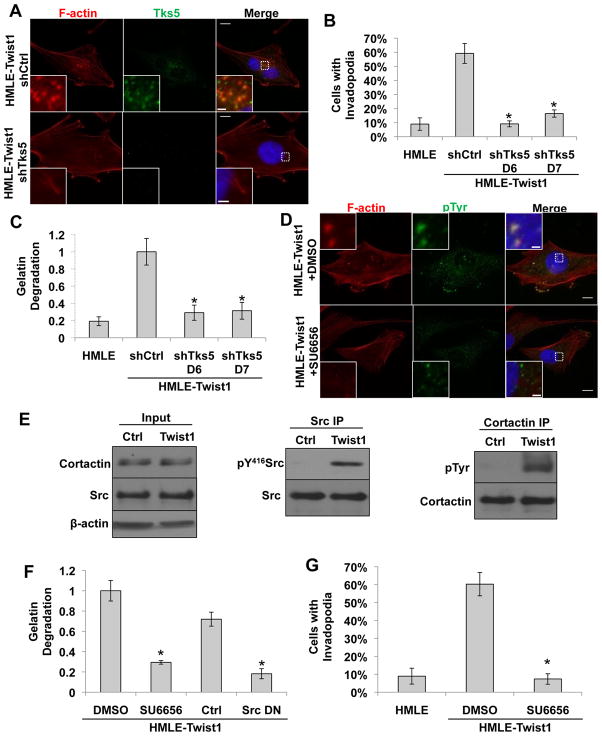

Twist1-mediated matrix degradation is invadopodia-driven and Src-dependent

Since both invadopodia-associated proteases and secreted proteases can mediate matrix degradation, we next set out to determine whether invadopodia, not secreted proteases, are solely responsible for Twist1-induced matrix degradation. In HMLE-Twist1 cells, we expressed shRNAs against Tks5, an adaptor protein that is required for invadopodia formation, but not MMP secretion (Seals et al., 2004). Both shRNAs effectively suppressed Tks5 expression (Figure S3A), and gelatin zymography showed that knockdown of Tks5 did not affect the secretion of proteases, mainly MMP2, into conditioned media (Figure S3B). In contrast, suppression of Tks5 significantly reduced their abilities to form invadopodia (Figure 3A and 3B) and degrade FITC-gelatin matrix (Figure 3C). Complementary to these data, Boyden chamber migration and invasion assays showed that suppression of Tks5 inhibited the ability of HMLE-Twist1 cells to invade through Matrigel, but did not affect cell migration (Figure S3C and S3D). Together, these results demonstrate that the protease activity associated with invadopodia is the sole mediator of Twist1-induced matrix degradation.

Figure 3. Twist1-mediated matrix degradation is invadopodia-driven and Src-dependent.

A. HMLE-Twist1 cells expressing a control or Tks5 shRNA were plated on 0.2% gelatin and stained for Tks5 (green) or phosphotyrosine (green) and F-actin (red).

B. Quantification of cells with invadopodia. N=150 cells/sample. *p<0.02.

C. Quantification of FITC-gelatin degradation. N=150 cells/sample. *p<0.02.

D. HMLE-Twist1 cells were plated on 0.2% gelatin and treated with treated with DMSO or 5μM SU6656 for 12 hours and stained for phosphotyrosine (green) and F-actin (red).

E. Cortactin and Src were immunoprecipitated from HMLE control and HMLE-Twist1 cell lysates, analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and probed for cortactin and phosphotyrosine and Src and pTyr416Src, respectively. Input lysates were probed for β-actin, Src, and cortactin.

F. Quantification of FITC-gelatin degradation. Indicated cells were treated with 5 μM SU6656 or DMSO for 12 hours or transfected with control or SrcK295M/Y527F vectors. N=150 cells/sample. *p<0.02.

G. Quantification of cells with invadopodia. N=150 cells/sample. *p<0.02.

Error bars are SEM. Scale bars are 1 μm for insets, 5 μm for full images.

See also Figure S3.

We next set out to understand how Twist1 promotes invadopodia formation. While no transcription factor has been implicated in invadopodia regulation, tyrosine phosphorylation of invadopodia components, including cortactin and Tks5, is necessary for invadopodia formation (Ayala et al., 2008). We therefore assessed whether tyrosine phosphorylation at invadopodia was increased in HMLE-Twist1 cells. Immunofluorescence staining with a phosphotyrosine antibody revealed enrichment of phosphotyrosine at invadopodia (Figure 3D). Cortactin immunoprecipitated from HMLE-Twist1 cells also showed increased tyrosine phosphorylation compared to HMLE control cells (Figure 3E).

Src family kinases are the major kinases that promote tyrosine phosphorylation and formation of invadopodia. We therefore examined whether Twist1 induced expression of any of the three major Src family kinases, Src, Yes, and Fyn. Both real-time RT-PCR and immunoblotting analyses showed that none of the three Src kinases were greatly induced by Twist1 (Figure S3E, S3F, and 3E). Interestingly, when we probed for the activation status of Src, Yes, and Fyn in HMLE-Twist1 cells using an antibody recognizing the active form of Src family kinases (phosphotyrosine 416), Src was significantly activated upon Twist1 expression (Figure 3E), while Yes and Fyn phosphorylation remained constant (Figure S3F). These data suggest that activation of Src kinase activity, but not transcriptional induction of Src kinase expression, might be responsible for tyrosine phosphorylation at invadopodia in HMLE-Twist1 cells. To determine whether Src kinase activity is required for Twist1-induced invadopodia function, we treated HMLE-Twist1 cells with SU6656, a selective inhibitor of Src family kinases (Blake et al., 2000) (Figure S3G) or expressed a dominant-negative Src (SrcK295M/Y527F) (Figure S3H). Both treatments reduced the ability of HMLE-Twist1 cells to degrade matrix by 5-fold (Figure 3F), indicating that Src kinase activity is essential for Twist1–mediated invadopodia function. Treatment with SU6656 also inhibited colocalization of the phosphotyrosine signal with F-actin (Figure 3D) and caused a significant reduction in the number of cells that formed invadopodia (Figure 3G). Together, these results indicate that Twist1-induced invadopodia formation and function is dependent on activation of the Src kinase.

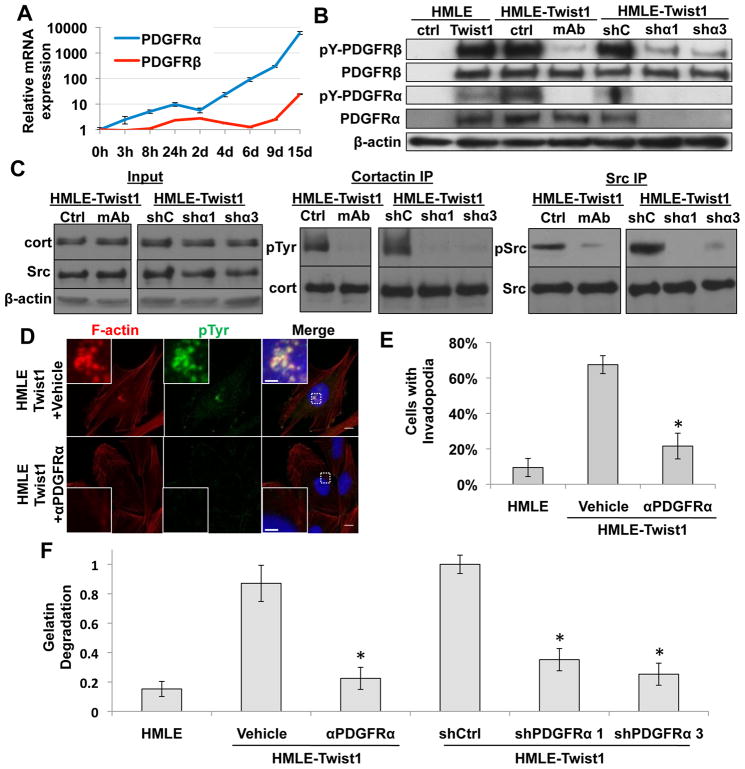

Twist1-induced PDGFR expression and activation is required for invadopodia formation

As a transcription factor, Twist1 cannot directly activate Src kinase, so we probed how Twist1 promotes activation of Src in HMLE-Twist1 cells. Since activation of Src kinase is downstream of growth factor receptor (GFR) activation, we examined induction of known GFRs upstream of Src by Twist1. Using an inducible Twist1 (Twist1-ER) construct (Mani et al., 2008), we found that expression of PDGFRα mRNAs increased 3-fold within 3 hours of Twist1 activation and reached over 6000-fold induction at Day 15, while induction of PDGFRβ mRNAs occurred significantly later (Figure 4A). PDGFRs can directly activate Src family kinases by tyrosine phosphorylation (Kypta et al., 1990), and activation of a PDGF autocrine loop is associated with the EMT program (Jechlinger et al., 2003). We found that PDGFRα and β proteins were also induced in HMLE-Twist1 cells and both PDGFR α and β were phosphorylated at tyrosine residues corresponding to their active states (Figure 4B). This activation of PDGFR without exogenous PDGF ligands implies the existence of an autocrine activation loop in vitro most likely mediated by PDGF-C, the only PDGF ligand significantly expressed and upregulated upon activation of Twist1 in HMLE cells (Figure S4A). Upregulation of PDGFRs by Twist1 therefore presented a potential mechanism for activation of Src by Twist1.

Figure 4. Twist1-induced PDGFR expression and activation is required for invadopodia formation.

A. Real-time PCR analysis of PDGFRα and PDGFRβ expression in HMLE-Twist1-ER cells treated with 20 nM 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen.

B. Cell lysates from HMLE control, HMLE-Twist1 cells, HMLE-Twist1 cells treated with vehicle or 8μg/ml PDGFRα blocking antibody (ctrl and mAb), and HMLE-Twist1 cells expressing control (shC) or PDGFR (shα1 and 3) shRNA were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and probed for β-actin, PDGFRα, PDGFRβ, pTyr754PDGFRα, and pTyr1009PDGFRβ.

C. Cortactin and Src were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates of HMLE-Twist1 cells treated with 8 μg/mL PDGFRα blocking antibody (mAb) or vehicle control (ctrl) or HMLE-Twist1 cells expressing indicated shRNAs (control, shC; shPDGFRα, shα1 and shα3) and probed for total cortactin and phosphotyrosine or total Src and pTyr419Src, respectively. Input lysates were probed for β-actin, cortactin, and total Src.

D. HMLE-Twist1 cells were seeded on 0.2% gelatin and treated for 24 hours with 8 μg/mL PDGFRα blocking antibody (αPDGFRα) or vehicle control and stained for phosphotyrosine (green), F-actin (red), and nuclei (blue). Scale bars are 1 μm for insets, 5 μm for full images.

E. Quantification of cells with invadopodia. N=150 cells/sample. *p<0.02.

F. Quantification of FITC-gelatin degradation. N=150 cells/sample. *p<0.02.

Error bars are SEM.

See also Figure S4.

We next set out to determine whether activation of PDGFRs is required for Twist1-induced invadopodia formation and matrix degradation. Given the immediate and robust induction of PDGFRα upon Twist1 activation, we focused on inhibiting PDGFRα to examine its role in mediating Twist1-induced Src activation and invadopodia formation. We first treated the HMLE-Twist1 cells with a monoclonal blocking antibody against PDGFRα and examined invadopodia formation and matrix degradation. This antibody effectively inhibited PDGFRα activation (Figure 4B), Src activation, and tyrosine phosphorylation of cortactin in HMLE-Twist1 cells (Figure 4C). This PDGFRα blocking antibody significantly inhibited invadopodia formation and tyrosine phosphorylation at invadopodia and suppressed the ability of HMLE-Twist1 cells to degrade FITC-gelatin by over 5-fold (Figure 4D–4F). To verify the results observed with the PDGFRα blocking antibody, we also expressed two independent shRNAs against PDGFRα in HMLE-Twist1 cells to stably suppress and inhibit PDGFRα signaling. Both shRNAs potently suppressed PDGFRα expression (Figure 4B), Src activation, and cortactin phosphorylation (Figure 4C), and effectively suppressed the ability of HMLE-Twist1 cells to degrade matrix (Figure 4F). Importantly, expression or secretion of proteases was not affected by PDGFRα knockdown as measured with gelatin zymography (Figure S4B). Together, these data indicate that PDGFRα expression and activation is required for Twist1-induced invadopodia formation and invasion.

We also examined expression of PDGFRα in 168FARN cells expressing control and Twist1 knockdown constructs. PDGFRα was highly expressed in control cells and significantly reduced upon knockdown of Twist1 (Figure S4C). These results provide further evidence that expression of PDGFRα depends on the presence of Twist1 in breast tumor cells.

Twist1 is a central mediator of invadopodia formation in response to EMT-inducing signals

Since other inducers of EMT, such as TGFβ and Snail, have also been associated with tumor invasion and metastasis, we sought to understand whether invadopodia formation also occurs in response to other EMT-inducing signals and whether Twist1 mediates invadopodia formation in response to these signals.

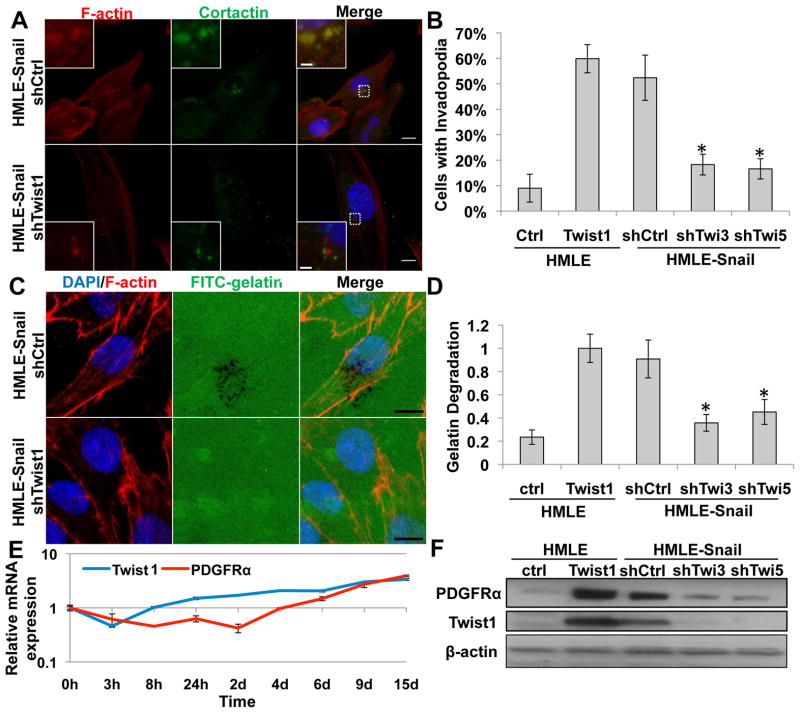

To do so, we first tested the ability of Snail, another EMT-inducing transcription factor, to promote invadopodia formation and matrix degradation. As previously reported, Snail overexpression induces EMT similarly to Twist1 in HMLE cells (Mani et al., 2009). HMLE-Snail cells have similar numbers of invadopodia and ECM-degradation activities as HMLE-Twist1 cells (Figure 5A–D). To determine whether Snail, like Twist1, could induce the expression of PDGFRα to promote invadopodia formation, we examined the expression of PDGFRα mRNA in HMLE cells that express an inducible Snail (Snail-ER) construct. In contrast to the immediate induction of PDGFRα upon Twist1 activation, PDGFRα mRNA only began to increase 6 days after Snail activation, indicating that induction of PDGFRα by Snail is indirect (Figure 5E). Interestingly, endogenous Twist1 mRNA levels increased significantly after 4 days of Snail activation, before PDGFRα mRNA began to increase (Figure 5E). These data suggest that induction of endogenous Twist1 could be responsible for PDGFRα expression and invadopodia formation upon Snail activation.

Figure 5. Twist1 is required for Snail-induced invadopodia formation.

A. HMLE-Snail cells expressing indicated shRNA were seeded on 0.2% gelatin for 72 hours, and stained for cortactin (green), F-actin (red), and nuclei (blue).

B. Quantification of cells with invadopodia. N=150 cells/sample. *p<0.02.

C. HMLE-Snail cells expressing control or Twist1 shRNA were seeded on FITC-gelatin (green) for 8 hours and stained for F-actin (red) and nuclei (blue).

D. Quantification of FITC-gelatin degradation. N=150 cells/sample. *p<0.02.

E. Real-time PCR analysis of PDGFRα and Twist1 mRNA expression in HMLE-Snail-ER cells treated with 20 nM 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen.

F. Cell lysates from indicated cells were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and probed for PDGFRα, Twist1, and β-actin.

Error bars are SEM. Scale bars are 1 μm for insets, 5 μm for full images.

See also Figure S5.

To assess whether Twist1 mediates the induction of invadopodia and PDGFRα in HMLE-Snail cells, we expressed shRNAs against endogenous Twist1 in HMLE-Snail cells. Indeed, suppression of endogenous Twist1 significantly inhibited expression of PDGFRα in HMLE-Snail cells (Figure 5F). Significantly, suppression of Twist1 expression inhibited invadopodia formation in HMLE-Snail cells and reduced their ability to degrade matrix (Figure 5A–5D). Importantly, HMLE-Snail cells that express shRNAs against Twist1 presented an EMT phenotype with loss of E-cadherin expression and a mesenchymal morphology (Figure S5A and S5B), indicating that suppression of E-cadherin by Snail and induction of invadopodia by Twist1 are regulated independently. Treating HMLE-Snail cells with the PDGFRα blocking antibody also significantly suppressed the ability of HMLE-Snail cells to degrade FITC-gelatin (Figure S5C and S5D). Together, these results indicate that Twist1 and PDGFRα are responsible for invadopodia formation in response to Snail activation.

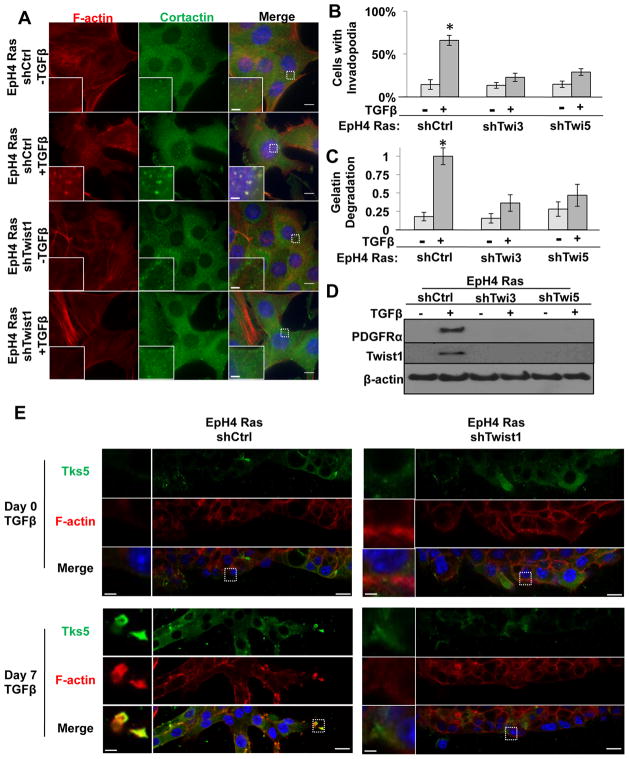

To further generalize our finding, we also investigated the role of Twist1 and PDGFRα in regulating invadopodia formation in response to TGFβ. In EpH4 mouse mammary epithelial cells, TGFβ has been shown to collaborate with Ras to promote EMT and activates an autocrine PDGF loop (Jechlinger et al., 2003). When we examined the invadopodia formation and matrix degradation in EpH4-Ras cells treated with TGFβ, we found that TGFβ treatment induced over 5-fold increase of invadopodia formation and matrix degradation in 2D culture (Figure 6A–6C). When these cells grew in 3D culture with TGFβ, invadopodia were visible at the leading edge of cells invading out of the organoids (Figure 6E). Interestingly, both Twist1 and PDGFRα were induced in response to TGFβ treatment (Figure 6D). When endogenous Twist1 induction was inhibited by shRNAs, invadopodia formation and matrix degradation were significantly reduced in 2D and 3D cultures (Figure 6A–6C, and 6E). Importantly, knocking down Twist1 abolished induction of PDGFRα in EpH4-Ras cells treated with TGFβ (Figure 6D), but did not prevent induction of EMT morphogenesis and loss of E-cadherin (Figure S6A and S6B), similar to knockdown of Twist1 in HMLE-Snail cells. Furthermore, treating EpH4-Ras cells with the PDGFRα inhibitor ST1571 significantly suppressed their ability to degrade FITC-gelatin in response to TGFβ treatment (Figure S6C and S6D). Importantly, treatment with STI571 did not revert the EMT phenotype (Figure S6E). Together, these results support our conclusion that Twist1 is a central mediator of invadopodia formation and matrix degradation via induction of PDGFRα in response to EMT-inducing signals.

Figure 6. Twist1 is required for TGFβ-induced invadopodia formation in Eph4Ras cells.

A. Eph4Ras cells expressing control or Twist1 shRNAs were seeded on 0.2% gelatin for 72 hours before and after treatment with 5 ng/ml TGFβ1 for seven days and stained for cortactin (green), F-actin (red), and nuclei (blue).

B. Quantification of cells with invadopodia before and after seven days of 5 ng/ml TGFβ1 treatment for EpH4Ras cells expressing indicated shRNAs. N=150 cells/sample. *p<0.02.

C. Quantification of FITC-gelatin degradation for cells expressing indicated shRNA before and after seven days of 5 ng/ml TGFβ1 treatment. N=150 cells/sample. *p<0.02.

D. Cell lysates from indicated cells before and after treatment with 5 ng/mL TGFβ1 for seven days were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and probed for PDGFRα, Twist1, and β-actin.

E. Indicated cells were embedded in 1:1 mixture of Matrigel and collagen, allowed to form 3D structures, and processed for IF before and after 7 days of induction with 7 ng/ml TGFβ1. Cells were stained for Tks5 (green) and F-actin (red).

Error bars are SEM. Scale bars are 1 μm for insets, 5 μm for full images.

See also Figure S6.

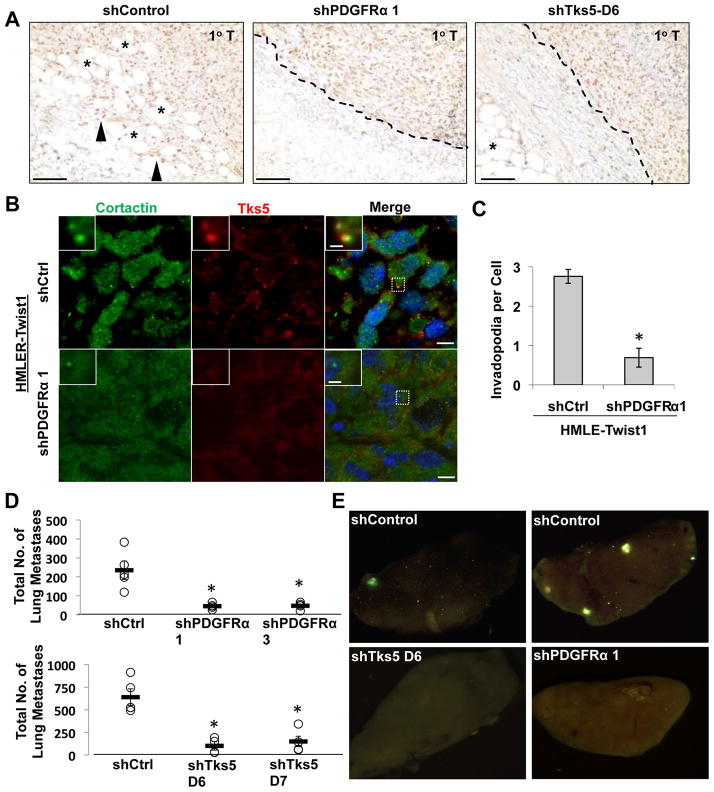

Twist1-induced metastasis is mediated by invadopodia in vivo and requires PDGFRα

Twist1 is required for mammary tumor cells to metastasize from the mammary gland to the lung. We then tested whether PDGFRα and invadopodia are required for the ability of Twist1 to promote tumor metastasis in vivo. To do so, we generated HMLE-Twist1 cells that were transformed with oncogenic Ras (HMLER-Twist1) and expressed shRNAs against either PDGFRα or a control shRNA. These cells also expressed GFP to allow identification of tumor cells in mice. Individual cell lines were injected subcutaneously into nude mice. Suppression of PDGFRα did not affect cell proliferation in culture or tumor growth rate in vivo (Figure S7A and S7B). Six weeks after tumor implantation, we sacrificed the mice and examined primary tumors for histology and invadopodia. Since HMLER-Twist1 tumors expressing large T antigen, we used an antibody against large T antigen to stain implanted tumor cells. Interestingly, HMLER-Twist1 tumor cells invaded into surrounding stroma and adjacent adipose tissue, while PDGFRa knockdown inhibited local invasion and tumor cells remained encapsulated (Figure 7A). Staining for invadopodia using cortactin and Tks5 in sections of primary tumor tissue revealed that HMLER-Twist1 tumor cells contained abundant invadopodia, while knocking down PDGFRα significantly reduced their occurance (Figure 7B and 7C). To test whether PDGFRα is required for distant metastasis, examination of lung lobes and sections revealed clusters of HMLER-Twist1 shControl cells throughout the lungs (Figure 7E and S7E). Significantly, suppression of PDGFRα expression significantly reduced the number of disseminated tumor cells in the lung (Figure 7D). These results strongly indicate that induction of PDGFRα is required for the ability of Twist1 to form invadopodia and promote tumor metastasis without affecting primary tumor growth in vivo.

Figure 7. Twist1-induced metastasis is mediated by invadopodia in vivo and requires PDGFRα.

A. Representative images of primary tumor paraffin tissue sections stained with SV40 Large-T antigen IHC and counterstained with hematoxylin. Tumor margin is indicated with dashed line when apparent. Closed triangles indicate invasive, Large-T positive tumor cells. Asterisks indicate adjacent adipose tissue. Scale bars are 100 μm.

B. Images of sections of primary tumors stained with cortactin (green), Tks5 (red), and DAPI (blue). Scale bars are 1 μm for insets, 5 μm for full images.

C. Quantification of number of invadopodia (cortactin/Tks5 colocalization) per cell. N=150 cells/sample. *p<0.02.

D. Quantification of total number of GFP positive tumor cells (HMLER-Twist1 cells expressing indicated shRNAs) in individual lungs. N=5 mice per group.

E. Representative images of lungs from mice injected with HMLER-Twist1 cells expressing indicated shRNAs show a decrease in dissemination of GFP positive tumor cells (green) to the lungs upon knockdown of PDGFRα or Tks5.

Error bars are SEM.

See also Figure S7.

To demonstrate that invadopodia are required for the ability of Twist1 to metastasize in vivo, we expressed shRNAs against Tks5 to inhibit invadopodia formation in HMLER-Twist1 cells. Knockdown of Tks5 did not affect cell growth rate in vitro (Figure S7C). These cells were implanted subcutaneously into nude mice to follow primary tumor growth and lung metastasis. Consistent with the results from the PDGFRα knockdown experiments, Tks5 knockdown inhibited local tumor invasion and significantly reduced the numbers of tumor cells that disseminated into the lung, while primary tumor growth was not affected (Figure 7A, 7D, 7E, and S7D). Together, these data demonstrate that induction of invadopodia formation via PDGFRα activation is essential for the ability of Twist1 to promote tumor metastasis in vivo.

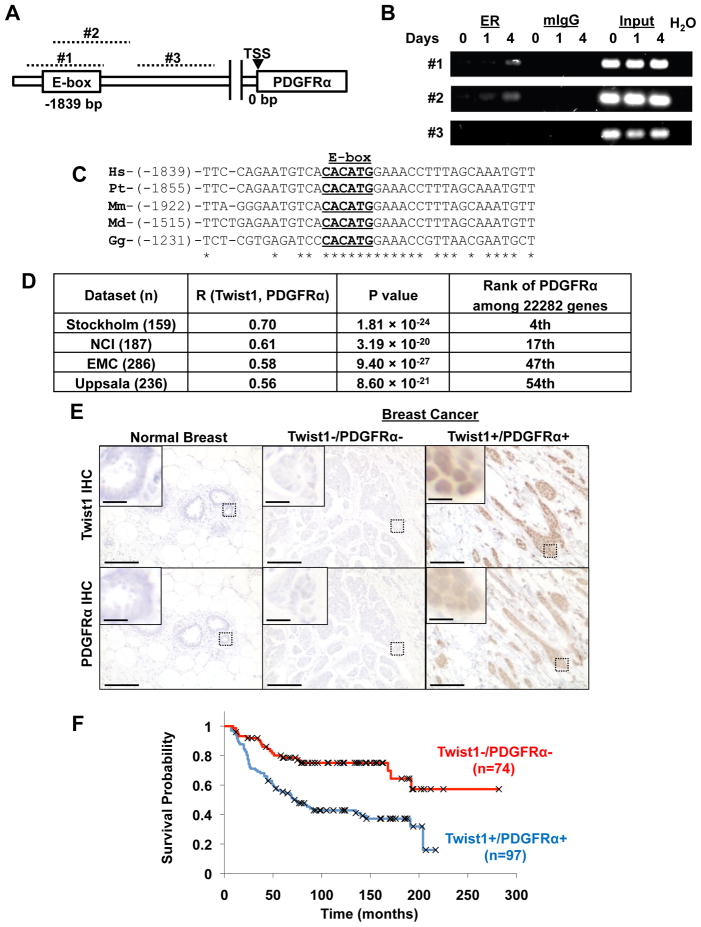

PDGFRα is a direct transcription target of Twist1 and expression of Twist1 and PDGFRα are tightly linked in human breast tumors

Given the immediate induction of PDGFRα by Twist1 and their tight association in various tumor cells, we set out to determine whether PDGFRα is a direct transcriptional target of Twist1. We examined the human PDGFRα promoter for potential Twist1-binding E-box sequences (CANNTG). We designed three sets of primers on the putative promoter: primer sets 1 and 2 target the identified E-box, and primer set 3 targets an adjacent region lacking the putative E-box (Figure 8A). By chromatin immunoprecipitation, we found that Twist1 directly bound to the E-box on the putative PDGFRα promoter (Figure 8B). Twist1 was able to activate the isolated human PDGFRa promoter in an E-box-dependent fashion in a luciferase reporter assay (Figure S8A and S8B). Furthermore, this consensus E-box sequence is highly conserved between all mammalian species examined and chickens (Figure 8C), indicating that induction of PDGFRα by Twist1 is direct and evolutionally conserved.

Figure 8. PDGFRα is a direct target of Twist1 and expression of Twist1 and PDGFRα is negatively correlated with survival.

A. Schematic of the human PDGFRα gene promoter region with conserved E-box element 1839 bp upstream of transcriptional start site (TSS), and regions targeted by three primer pairs (#1–3, dashed lines). Primer pairs #1 and #2 target the putative E-box while primer pair #3 targets a downstream region lacking a conserved E-box.

B. HMLE-Twist1-ER cells were treated with 20 nM 4-hydroxytamoxifen for 0, 1, or 4 hours. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated using estrogen receptor antibody and PCR was performed on the ChIP product using three primer pairs.

C. Alignment of conserved E-box (underlined) in PDGFRα promoter. Number in parenthesis indicates distance upstream from transcription start site. Hs=Homo sapiens, Pt=Pan troglodytes, Mm=Mus musculus, Md=Monodelphus domesticus, Gg=Gallus gallus.

D. Correlation of Twist1 and PDGFRα in four human breast cancer expression array datasets. R is the correlation coefficient.

E. Representative images of normal human breast tissue or human breast cancer samples stained for Twist1 and PDGFRα. Scale bar is 5 μm for inset, 100 μm for full images.

F. Kaplan-Meier survival curve for samples classified as high PDGFRα/high Twist1 expression and low PDGRα/low Twist1 by IHC analysis. Censored data are indicated with X.

To more directly probe the in vivo association between Twist1 and PDGFRα in human breast tumor samples, we analyzed four published large human breast tumor gene expression datasets summarizing 860 primary breast cancers (Pawitan et al., 2005; Sotiriou et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2005; Miller et al., 2005). In each data set, we calculated the rank-based Spearman correlation coefficient between Twist1 and all 22282 genes on the array, including PDGFRa. PDGFRα was consistently among the top ranked genes associated with Twist1 (4th, 17th, 47th, and 54th out of 22282 genes) in all four breast cancer datasets (Figure 8D and S8D). Expression of Twist1 and PDGFRα were positively correlated with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.56 to 0.70 (Figure 8D and S8C). Furthermore, in all four data sets, PDGF ligand expression correlated with PDGFRα and Twist1 expression in over 95% of tumor samples (Table S1), indicating that PDGFRα could be active in these samples. To further access whether coexpression of Twist1 and PDGFRα could affect survival in breast tumor patients, we stained Twist1 and PDGFRα in a set of human invasive breast tumor tissue array samples and found that co-expression of Twist1 and PDGFRα was negatively associated with long-term survival (Figure 8E and 8F). Together, these data provides further support for a direct and functional association between Twist1 and PDGFRα in human breast cancers and suggests that regulation of invadopodia by Twist1 and PDGFRα contributes to human breast cancer progression.

Discussion

Our study has identified a unique function of the Twist1 transcription factor in promoting invadopodia formation and matrix degradation during tumor metastasis. We demonstrate that transcriptional induction of PDGFRα and activation of Src by Twist1 are essential for invadopodia formation and matrix degradation. Induction of PDGFRα and invadopodia formation is also essential for the ability of Twist1 to promote metastasis in vivo. Twist1 and PDGFRα are central mediators of invadopodia in response to several EMT-inducing signals. Finally, we provide evidence for a tight association between Twist1 and PDGFRα in human breast tumor samples.

Induction of invadopodia by Twist1 plays a key role in extracellular matrix degradation and metastasis

ECM degradation is considered a key step promoting tumor invasion and metastasis. Extensive studies have largely focused on secreted MMPs as key proteases in tumor invasion. More recent studies suggest a role for invadopodia and their associated proteases in localized matrix degradation during cell invasion. Conceptually, invadopodia provide an elegant solution to restrict protease activity to areas of the cell in direct contact with ECM, thus precisely controlling cell invasion in vivo. In this study, we show that Twist1, a key transcription factor in tumor metastasis, is both necessary and sufficient to promote invadopodia formation. Importantly, invadopodia formation is required for the ability of Twist1 to promote tumor metastasis in vivo. Together, these results demonstrate an essential role for invadopodia in tumor invasion and metastasis in vivo.

How invadopodia formation is regulated at the molecular level is still not well understood. Our current study indicates that Twist1 directly induces the expression and activation of PDGFRα, thus promoting Src kinase activation and invadopodia formation. Although we did not detect induction of several important invadopodia proteins, including cortactin, Tks4, Tks5, and MT1-MMP, by Twist1 (data not shown), we are actively exploring additional mechanisms by which Twist1 regulates invadopodia.

Another question arising from our study is whether invadopodia function is required for the EMT process. Epithelial cells sit on top of a layer of basement membrane. For the EMT program to occur in vivo, these cells must breach the underlying basement membrane to dissociate (Nakaya et al., 2008). Little is known about the functional relationship between basement membrane integrity and the EMT program. In HMLE-Snail cells and EpH4-Ras cells treated with TGFβ, knockdown of Twist1 inhibited invadopodia formation, while these cells underwent the morphological changes associated with EMT and lost E-cadherin expression. Additionally, knockdown of Tks5, a required component of invadopodia, did not revert the EMT phenotype in HMLE-Twist1 cells. These results indicate that invadopodia function is not essential for EMT to occur in 2D cultures. However, it is plausible that the EMT program requires activation of Twist1 and invadopodia formation to allow degradation of the basement membrane in vivo. Studies in vivo or in 3D cultures with intact basement membrane are required to fully answer this question.

Twist1 and Snail have distinct cellular functions and transcriptional targets

The EMT program is considered a key event promoting carcinoma cell dissociation, invasion, and metastasis. Several transcription factors, including Snail, Slug, ZEB1, ZEB2, and Twist1, promote EMT in epithelial cells (Peinado et al., 2007). During mesoderm formation and neural crest development, these transcription factors are activated to allow the dissociation and migration of epithelial cells. A major unsolved question is to determine the distinct cellular functions and molecular targets of individual EMT-inducing transcription factors. Extensive studies in recent years have demonstrated that Snail (Batlle et al., 2000; Cano et al., 2000), Slug (Hajra et al, 2002), and ZEB2 (Comijin et al., 2001), all zinc-finger-containing transcriptional repressors, directly bind to the E-boxes on the E-cadherin promoter and suppress its transcription. In this study, we identified a unique function of Twist1 in promoting matrix degradation via invadopodia. We show that Twist1 functions as a transcriptional activator to directly induce the expression of PDGFRα, in contrast to the EMT-inducing Zn-finger transcription factors.

Vertebrate Twist1 lacks a transcription activation domain and requires dimerization with other bHLH transcription factors to activate transcription. Previous studies have shown Twist1 heterodimers with MyoD function as transcriptional repressors (Hamamori et al., 1997). In contrast, heterodimerization with E12 enables Twist1 to activate FGF2 transcription (Laursen et al, 2007). Here we demonstrate that Twist1 functions as a transcriptional activator to directly induce the transcription of PDGFRα. Twist1 might function as an activator or repressor of transcription based on dimerization partners under different physiological and cellular environments. The factors that heterodimerize with Twist1 to activate PDGFRα transcription remain unknown, although the E12/E47 proteins could perform this function.

The pathway linking Twist1, PDGFR, and invadopodia is likely to play a conserved role in matrix degradation during both tumor metastasis and embryonic morphogenesis

Twist1 has been associated with increased metastasis in both experimental tumor metastasis models and in many types of human cancers. Interestingly, PDGFRα overexpression and activation have also been observed in aggressive human breast tumors (Seymour and Bezwoda, 1994; Jechlinger et al, 2006). Activation of PDGFRs was first observed in TGFβ-induced EMT and shown to be involved in cell survival during EMT and experimental metastasis in mice (Jechlinger et al., 2006). Here, we demonstrated a role of PDGFRα in invadopodia formation and matrix degradation during tumor metastasis. Interestingly, suppression of PDGFRα had no significant effects on cell proliferation or survival in vitro and in vivo. These results could be due to the greater specificity of shRNAs compared to chemical inhibition as well as differences in cellular and signaling contexts. Indeed, we found that STI571 (Gleevec), a c-ABL and c-Kit inhibitor that also inhibits PDGFR at a higher concentration, suppressed Twist1-induced invadopodia formation and matrix degradation. However, long-term (four days) treatment with STI571 resulted in cell toxicity in HMLE-Twist1 cells (data not shown).

Our analyses identified Twist1 as a transcription inducer of PDGFRα and demonstrate a tight correlation between the expression level of Twist1 and PDGFRα in four large human breast tumor gene expression studies. Interestingly, PDGF ligand was also present in over 95% of tumor samples that expressed Twist1 and PDGFRα, indicating PDGFRα is activated in these tumors. Although these two genes alone are not sufficient to predict survival with statistical significance in these studies, these data, together with our metastasis data in mice and human breast cancer tissue array data, strongly suggest their involvement in breast cancer progression. Twist1, as a transcription factor, is difficult to target therapeutically. As a downstream target of Twist1 with roles in tumor invasion, PDGFRα might be a potentially valuable target for future therapeutics against metastasis.

Although our study focuses on the role of Twist1-induced invadopodia in metastasis, it also has important implications in development. Twist1 null mice and PDGFRα null mice both show defects in cranial neural crest development (Chen and Behringer, 1995, Sun et al., 2000). In addition, the expression pattern of Twist1 and PDGFRα are similar along the developing neural crest and craniofacial region in developing mouse embryos (Gitelman, 1997, Takakura et al., 1997). Our identification of PDGFRα as a highly conserved transcriptional target of Twist1 suggests that the pathway linking Twist1, PDGFRα, and invadopodia might play a key role in regulating neural crest development. Reactivation of this developmental machinery in tumor metastasis is another example of an important developmental pathway regulating tumor progression.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Lines

67NR, 168FARN, 4T1 cells and the human mammary epithelial cell lines HMLE and HMLER were cultured as described (Yang et al., 2004). EpH4Ras cells were passaged in mammary epithelial growth media (MEGM) mixed 1:1 with DMEM/F12 supplemented with human EGF, insulin, and hydrocortisone.

Viral Production and Infection

Stable cell lines were created via infection of target cells using either lentiviruses or Moloney viruses. 293T cells were seeded at 1×106 cells per 6cm dish in DMEM/10%FBS. After 18 hours, cells were transfected as follows: 6μL TransIT-LT1 (Mirus Bio) was added to 150 μL DMEM and incubated 20 minutes. 1μg of viral vector along with 0.9μg of the appropriate gag/pol expression vector (pUMCV3 for pBabe or pWZL or pCMV 8.2R for lentiviral vectors) and 0.1μg VSVG expression vector were then added to the DMEM/LT-1 mixture. The mixture was incubated 30 minutes and then added to 293T cells overnight. Next day fresh media were added to the transfected 293T cells. Viral supernatant was harvested at 48 and 72 hours post transfection, filtered, and added to the recipient cell lines with 6 μg/ml protamine sulfate for 4 hours infection. HMLE and EpH4Ras cells were then selected with 2 μg/ml puromycin, or 10 μg/ml blasticidin.

Plasmids

The Twist1 and Snail cDNAs and the Twist1-ER and Snail-ER in the pWZL-Blast vector were described in Mani et al, 2009. The three shRNA lentiviral constructs against Twist1 in the pSP108 vector were described in Yang et al, 2004. The shRNA lentiviral constructs against Tks5 in the pLKO vector were provided by Dr. Sara Courtneidge. The shRNAmir lentiviral constructs against PDGFRα in the pGIPZ vector were purchased from Open Biosystems. The oncogenic Ras (V12) was cloned into the pRRL lentiviral vector.

Real-Time PCR

Total RNAs were extracted from cells at 80–90% confluency using RNeasy Mini Kit coupled with DNase treatment (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed with High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). Resulting cDNAs were analyzed in triplicates using SYBR-Green Master PCR mix (Applied Biosystems). Relative mRNA concentrations were determined by 2−(Ct-Cc) where Ct and Cc are the mean threshold cycle differences after normalizing to GAPDH values. Primers used for PCR are listed in Supplemental Information.

Immunoprecipitation

Cells at 80–90% confluence were washed with PBS containing 100 μM Na3VO4 and lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCL, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM NaF, 100 μM Na3VO4, 2 mM DTT) containing 1:50 dilution Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Set III (Calbiochem). For immunoprecipitations, lysates were incubated with antibodies overnight at 4°C. 50 μL Protein G-Sepharose 4B conjugated beads (Invitrogen) were added for 12 hours at 4°C. Beads were washed in lysis buffer and in PBS containing 100 uM Na3VO4. Proteins were eluted from beads using SDS sample buffer and analyzed on 4–12% precast SDS gels (PAGEgel).

In situ zymography

This protocol is adapted from Artym et al. 2009. Briefly, 12 mm coverslips were incubated in 20% nitric acid for 2 hours, washed in H2O for 4 hours. Coverslips were incubated with 50 μg/mL poly-L-lysine/PBS for 15 min followed by PBS washes before 0.15% gluteraldehyde/PBS was added for 10 min, followed by PBS washes. Coverslips were inverted onto 20 μl droplets of 1:9 0.1% fluorescein isothiocyante (FITC)-gelatin (Invitrogen): 0.2% porcine gelatin for 10 minutes. Coverslips were washed in PBS and then incubated 15 min in 5 mg/ml NaBH4. Coverslips were rinsed in PBS and incubated at 37° in 10% calf serum/DMEM for 2 hours. 20,000 cells were seeded on each coverslip, incubated for 8 hours, and processed for immunofluorescence. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. Images were taken at ten fields per sample for a total of approximately 150 cells per sample. Gelatin degradation was quantified using ImageJ software. To measure the percentage of degraded area in each field, identical signal threshold for the FITC-gelatin fluorescence are set for all images in an experiment and the degraded area with FITC signal below the set threshold was measured by ImageJ. The resulting percentage of degradation area was further normalized to total cell number (counted by DAPI staining for nuclei) in each field. The final gel degradation index is the average percentage degradation per cell obtained from all 10 fields. Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Immunofluorescence

Matrix substrates were prepared using 0.2% porcine gelatin as for in situ zymography. Cells were fixed at 37°C in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA)/PBS with 50 μM CaCl2 for 15 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS for 10 min, and blocked with 5% goat serum. Samples were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C and with secondary antibodies and/or phalloidin for 2 hours. After washing, coverslips were mounted with VECTASHIELD (Vector Laboratories). All antibodies used and their dilutions are listed in Supplemental Information.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

Cells at 80% confluence were crosslinked with 4% PFA, lysed, and sonicated. Nuclear lysates were incubated with Protein G Dynabeads (Invitrogen) pre-conjugated with anti-estrogen receptor antibody overnight. DNA was reverse crosslinked and purified by phenol-chloroform and ethanol precipitation.

Subcutaneous tumor implantation and metastasis assay

All animal care and experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of California, San Diego. 1.5 million cells resuspended in 50% Matrigel were injected into the left and right flanks of Nude mice and allowed to grow to about 2 cm in diameter before mice were sacrificed. Primary tumor size was measured every five days. Lungs were harvested and imaged for GFP positive tumor cells. Tissues were embedded in paraffin, sectioned, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and imaged to identify GFP positive tumor cells.

Three Dimensional Cell Culture

Equal volumes of neutralized collagen I and Matrigel were mixed on ice and 20 μl added to the bottom of each well of an 8-chamber coverglass slide. Cells of interest were mixed with the Matrigel:collagen mix to give a final concentration of 200,000 cells per ml and 100 ul of the cell:matrix mixture added to each well. Media was changed every other day until establishment of spherical colonies. TGFβ1 was added at 5 ng/ml every other day for up to two weeks. Cells were fixed with 4% PFA and processed as described above for immunofluorescence.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin sections of human or mouse samples were rehydrated through xylene and graded alcohols. Antigen retrieval was accomplished using a pressure cooker in 10 mM sodium citrate 0.05% Tween. Samples were incubated with 3% H2O2 for 30 minutes followed by 5 hours blocking in 20% goat serum in PBS. Endogenous biotin and avidin were blocked using a Vector Avidin/Biotin blocking kit. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C in 20% goat serum. Biotinylated secondary antibody and Vectorstain ABC kit were used as indicated by manufacturer. Samples were developed with diaminobenzidine (DAB) and samples counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted with Permount.

Significance.

Studies suggest that the EMT-inducing transcription factors play critical roles in tumor metastasis. A major question is what are the cellular functions and transcriptional targets of individual EMT-inducing transcription factors required for tumor metastasis. Our study identifies a unique function of Twist1 in promoting invadopodia-mediated matrix degradation, which is essential for its ability to promote metastasis. Formation of invadopodia and loss of cell adhesion are regulated by different transcription factors. This explains why multiple factors need to be activated coordinately to promote carcinoma cells to undergo EMT and invade. We also identify PDGFRα as a direct transcriptional target of Twist1 in promoting invadopodia formation and tumor metastasis, therefore suggesting that PDGFRs might be potential targets for anti-metastasis therapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Sara Courtneidge and the members of her laboratory, especially Begoňa Diaz and Danielle Murphy, for their suggestions and for providing the antibody and shRNA constructs for Tks5. We thank Drs. Robert A. Weinberg, Alexandra Newton, Kun-Liang Guan, and other members of the Yang lab for their suggestions to the manuscript. We thank Dr. David Cheresh for providing Yes and Fyn antibodies. We thank Dr. Cornelis Murre for providing the E47 expression construct. We thank the NCI Cancer Diagnosis Program (CDP) for providing breast tumor tissue microarray slides. We thank the Shared Microscope Facility and UCSD Cancer Center Specialized Support Grant P30 CA23100. This work was supported by grants to J. Y. from NIH (DP2 OD002420-01), Kimmel Scholar Award, and California Breast Cancer Research Program (12IB-0065), by a NIH Molecular Pathology of Cancer Predoctoral Training grant and a DOD Breast Cancer Predoctoral fellowship (M.A.E), by an NIH Pharmacological Science Predoctoral Training grant (A.T.C), by a DOD Breast Cancer Era of Hope Postdoctoral Fellowship (E.D.), and by the Susan G. Komen Foundation grant FAS0703850 (J.K. and L.O.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abram CL, Seals DF, Pass I, Salinsky D, Maurer L, Roth TM, Courtneidge SA. The adaptor protein fish associates with members of the ADAMs family and localizes to podosomes of Src-transformed cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16844–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300267200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala I, Baldassarre M, Giacchetti G. Multiple regulatory inputs converge on cortactin to control invadopodia biogenesis and extracellular matrix degradation. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:369–78. doi: 10.1242/jcs.008037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artym VV, Yamada KM, Mueller SC. ECM degradation assays for analyzing local cell invasion. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;522:211–9. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-413-1_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batlle E, Sancho E, Franci C, Dominguez D, Monfar M, Baulida J, Garcia De Herreros A. The transcription factor snail is a repressor of E-cadherin gene expression in epithelial tumour cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:84–9. doi: 10.1038/35000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake RA, Broome MA, Liu X, Wu J, Gishizky M, Sun L, Courtneidge SA. SU6656, a selective Src family kinase inhibitor, used to probe growth factor signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:9018–27. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.9018-9027.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blouw B, Seals DF, Pass I, Diaz B, Courtneidge SA. A role for the podosome/invadopodia scaffold protein Tks5 in tumor growth in vivo. Eur J Cell Biol. 2008;87:555–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden ET, Onikoyi E, Slack R, Myoui A, Yoneda T, Yamada KM, Mueller SC. Co-localization of cortactin and phosphotyrosine identifies active invadopodia in human breast cancer cells. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:1240–53. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer B, Thiery JP. Epithelium-mesenchyme interconversion as example of epithelial plasticity. APMIS. 1993;101:257–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1993.tb00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschman MD, Bromann PA, Cejudo-Martin P, Wen F, Pass I, Courtneidge SA. The novel adaptor protein Tks4 (SH3PXD2B) is required for functional podosome formation. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1302–11. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-09-0949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, Perez-Moreno MA, Rodrigo I, Locascio A, Blanco MJ, del Barrio MG, Portillo F, Nieto MA. The transcription factor snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:76–83. doi: 10.1038/35000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WT. Proteolytic activity of specialized surface protrusions formed at rosette contact sites of transformed cells. J Exp Zool. 1989;251:167–85. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402510206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZF, Behringer RR. Twist is required in head mesenchyme for cranial neural tube morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 1995;9:686–99. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.6.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comijn J, Berx G, Vermassen P, Verschueren K, van Grunsven L, Bruyneel E, Mareel M, Huylebroeck D, van Roy F. The two-handed E box binding zinc finger protein SIP1 downregulates E-cadherin and induces invasion. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00260-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitelman I. Twist protein in mouse embryogenesis. Dev Biol. 1997;189:205–14. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grobelny D, Poncz L, Galardy RE. Inhibition of human skin fibroblast collagenase, thermolysin, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase by peptide hydroxamic acids. Biochemistry. 1992;31:7152–4. doi: 10.1021/bi00146a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajra KM, Chen DY, Fearon ER. The SLUG zinc-finger protein represses E-cadherin in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1613–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamori Y, Wu HY, Sartorelli V, Kedes L. The basic domain of myogenic basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) proteins is the novel target for direct inhibition by another bHLH protein, Twist. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6563–73. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay ED. An overview of epithelio-mesenchymal transformation. Acta Anat. (Basel) 1995;154:8–20. doi: 10.1159/000147748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jechlinger M, Grunert S, Tamir IH, Janda E, Lüdemann S, Waerner T, Seither P, Weith A, Beug H, Kraut N. Expression profiling of epithelial plasticity in tumor progression. Oncogene. 2003;22:7155–69. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jechlinger M, Sommer A, Moriggl R, Seither P, Kraut N, Capodiecci P, Donovan M, Cordon-Cardo C, Beug H, Grünert S. Autocrine PDGFR signaling promotes mammary cancer metastasis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1561–70. doi: 10.1172/JCI24652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypta RM, Goldberg Y, Ulug ET, Courtneidge SA. Association between the PDGF receptor and members of the src family of tyrosine kinases. Cell. 1990;62:481–92. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen KB, Mielke E, Iannaccone P, Füchtbauer EM. Mechanism of transcriptional activation by the proto-oncogene Twist1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:34623–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707085200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder S. The matrix corroded: podosomes and invadopodia in extracellular matrix degradation. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:107–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani SA, Yang J, Brooks M, Schwaninger G, Zhou A, Miura N, Kutok JL, Hartwell K, Richardson AL, Weinberg RA. Mesenchyme Forkhead 1 (FOXC2) plays a key role in metastasis and is associated with aggressive basal-like breast cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10069–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703900104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, Eaton EN, Ayyanan A, Zhou AY, Brooks M, Reinhard F, Zhang CC, Shipitsin M, et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:704–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LD, Smeds J, George J, Vega VB, Vergara L, Ploner A, Pawitan Y, Hall P, Klaar S, Liu ET, et al. An expression signature for p53 status in human breast cancer predicts mutation status, transcriptional effects, and patient survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13550–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506230102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaya Y, Sukowati EW, Wu Y, Sheng G. RhoA and microtubule dynamics control cell-basement membrane interaction in EMT during gastrulation. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:765–75. doi: 10.1038/ncb1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawitan Y, Bjöhle J, Amler L, Borg AL, Egyhazi S, Hall P, Han X, Holmberg L, Huang F, Klaar S, et al. Gene expression profiling spares early breast cancer patients from adjuvant therapy: derived and validated in two population-based cohorts. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:R953–64. doi: 10.1186/bcr1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peinado H, Olmeda D, Cano A. Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:415–28. doi: 10.1038/nrc2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seals DF, Azucena EF, Jr, Pass I, Tesfay L, Gordon R, Woodrow M, Resau JH, Courtneidge SA. The adaptor protein Tks5/fish is required for podosome formation and function, and for the protease-driven invasion of cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:155–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour L, Bezwoda WR. Positive immunostaining for platelet derived growth factor is an adverse prognostic factor in patients with advanced breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1994;32:229–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00665774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotiriou C, Wirapati P, Loi S, Harris A, Fox S, Smeds J, Nordgren H, Farmer P, Praz V, Haibe-Kains B, et al. Gene expression profiling in breast cancer: understanding the molecular basis of histologic grade to improve prognosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:262–72. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T, Jayatilake D, Afink GB, Ataliotis P, Nister M, Richardson WD, Smith HK. A human YAC transgene rescues craniofacial and neural tube development in PDGFRalpha knockout mice and uncovers a role for PDGFRalpha in prenatal lung growth. Development. 2000;127:4519–29. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.21.4519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takakura N, Yoshida H, Ogura Y, Kataoka H, Nishikawa S, Nishikawa SI. PDGFRα expression during mouse embryogenesis: immunolocalization analyzed by whole-mount immunohistostaining using the monoclonal anti-mouse PDGFRα antibody APA5. J Histochem Cytochem. 1997;45:883–93. doi: 10.1177/002215549704500613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarone G, Cirillo D, Giancotti FG, Comoglio PM, Marchisio PC. Rous sarcoma virus-transformed fibroblasts adhere primarily at discrete protrusions of the ventral membrane called podosomes. Exp Cell Res. 1985;159:141–57. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(85)80044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Klijn JG, Zhang Y, Sieuwerts AM, Look MP, Yang F, Talantov D, Timmermans M, Meijer-van Gelder ME, Yu J, et al. Gene-expression profiles to predict distant metastasis of lymph-node-negative primary breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365:671–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17947-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Mani SA, Donaher JL, Ramaswamy S, Itzykson RA, Come C, Savagner P, Gitelman I, Richardson A, Weinberg RA. Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell. 2004;117:927–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.