Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

To study the prevalence and risk factors of overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms and its relationship with symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse (POP).

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study including women aged between 45 and 85 years, registered in eight general practices. All women were asked to self complete the validated Dutch translated questionnaires. All symptoms were dichotomized as present or absent based on responses to each symptom and degree of bother.

Results

Forty-seven percent of the women filled out the questionnaire. Prevalence of urgency was 34% and the prevalence of any OAB symptoms 49%. Prevalence of OAB symptoms increased with advancing age. Symptoms of POP were an independent risk factor for symptomatic OAB. Other risk factors were continence and prolapse surgery in the past, age above 75, overweight, postmenopausal status and smoking.

Conclusions

The prevalence of any OAB symptoms was 49%. POP symptoms were an independent risk factor for symptomatic OAB.

Keywords: Overactive bladder, Urgency, Urge incontinence, Frequency, Pelvic organ prolapse, Prevalence

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms are important problems for women. POP is a prevalent problem which has been reported to affect 50% of parous women [1]. Eleven percent of the women will have undergone an operation for prolapse or urinary incontinence by the age of 80 [2].

OAB is known to be a highly prevalent disorder that increases with age in both sexes and that has a profound impact on quality of life [3]. According to the International Continence Society (ICS) OAB is defined as urgency with or without urge incontinence, usually with frequency and nocturia [4]. This term can only be used if there is no proven infection or ‘obvious pathology’. It is a matter of debate whether POP should be considered as ‘obvious pathology’.

Symptoms of OAB are often seen in patients with POP [5]. Community based studies showed that the prevalence of OAB symptoms is higher in patients with POP than without POP [5]. The same tendency is found in hospital based studies [5]. Nevertheless, the literature about the prevalence of the combination of POP and OAB is scarce.

To study the relation between POP and OAB, we used data from a cross-sectional study which was performed in a small Dutch city about the prevalence of pelvic floor symptoms in the general population [6].

The objective of this study is to investigate risk factors for OAB and specifically to explore the relationship between OAB and prolapse. This is important for clinical practice because the two diagnoses are often co-occurring which has possible consequences for diagnosis and treatment.

Methods

The study was cross-sectional in a small town, Brielle, in the Netherlands. Brielle was chosen because it has a homogenic population, where all women are registered in one of the nine general practices. All women aged 45 to 85 years registered on the patients lists of eight out of nine general practices were invited to enrol in the study, which is 95% of the women in this age group. The women were sent information about the study and informed that they could enrol by filling out an informed consent form. All women who consented were asked to complete a self-report questionnaire. Non-responders received a reminder 8 weeks later that contained the same questionnaire. To check for selection bias, permanent non-responders were invited to complete a short questionnaire that comprised five questions about age, parity, presence of stress urinary incontinence (yes/no), faecal incontinence (yes/no) and feeling of vaginal bulging (yes/no). To encourage a high response to the questionnaire, we used envelopes with the name and logo of the Erasmus University, coloured paper and stamped addressed return envelopes.

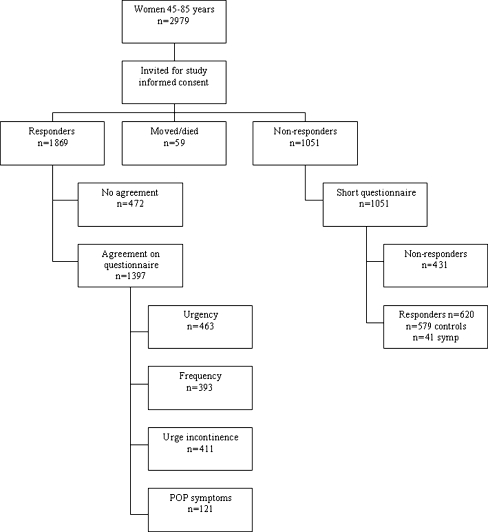

Three options were possible: women refused to participate in the study, women filled out only the questionnaire and women filled out the questionnaire and underwent vaginal examination. For the purpose of this study, data on vaginal examination are not used. The relation between symptoms and signs of vagina prolapse has been extensively described in an earlier study [6]. A flowchart of the study design is presented in Fig. 1. In this study, all women who answered the questionnaires are included.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study

The self-reported questionnaire used for this study are a composite of internationally well-known questionnaires that have been validated for the Dutch language. It contains, amongst others, disease-specific questions from the validated Dutch translation of the Urinary Distress Inventory(UDI) [7] next to other questionnaires and items which were not used for the present study [6].

Women rated the amount of bother of various symptom on a 5-point Likert scale, from 0 (no complaints at all) to 4 (very serious complaints). In addition, questions about ethnicity, parity, POP symptoms during pregnancy, family history, menopausal status, hormone replacement therapy (HRT), previous pelvic floor surgery, educational level, smoking and heavy physical work were also included.

The Medical Ethics Research Committee (METC) of the Erasmus MC in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, approved this study.

Measurements

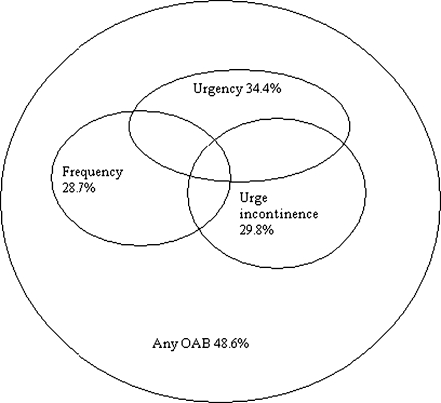

All symptoms were dichotomized as present or absent based on responses to each symptom and degree of bother with these symptoms. Women who denied the presence of a specific symptom as well as women who answered confirmative on a specific question but answered not to be bothered by it were considered as negative (absent) while women who indicated that they were little to severe bothered were considered as positive (present). The item of POP symptoms is merged from women who reported either seeing and/or feeling vaginal bulging. For the item any OAB symptoms, women who had urgency and/or frequency and/or urge incontinence symptoms were included (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Any OAB symptoms in relation to urgency, frequency and urge incontinence

Data are presented as number of women (percentage), mean (standard deviation) or median (range) as appropriate. Chi-square test was used to compare the difference between the women with- versus without POP symptoms.

Logistic regression was used for the univariate and multivariate analysis. For logistic regression, the backward elimination procedure was used. Variables with a P < 0.3 in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. We presented the odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI for each of the OAB symptoms. The level of significance was set at an alpha value of 0.05. All data were entered and analysed in a SPSS 15.0 database for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Of the 2,979 women who were eligible for this study, 1,397 (47%) filled out the questionnaire. In the non-responder group, 59% filled out and returned the short questionnaire (620/1,051), giving a total response rate of 62.7% (Fig. 1). Scores in the short questionnaire group were not significantly different from those in the total study group. Details of the response rate are presented in a previous report [6].

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the women included in this study. Table 2 shows the prevalence of OAB symptoms per age category. In Table 3, the prevalence of POP symptoms in women with and without OAB symptoms is presented.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics and details of previous pelvic operations

| Number of women | 1397 |

|---|---|

| Age (years)a | |

| 45–55 | 647 (46.9%) |

| 56–65 | 435 (31.5%) |

| 66–75 | 233 (16.9%) |

| 76–85 | 66 (4.8%) |

| Parity | |

| 0 | 120 (8.6%) |

| 1 | 215 (15.4%) |

| 2 | 675 (48.3%) |

| ≥3 | 387 (27.7%) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)b | |

| <20 | 53 (3.9%) |

| 20–25 | 599 (43.9%) |

| 25–30 | 519 (38.0%) |

| ≥30 | 193 (14.1%) |

| Racec | |

| Caucasian | 1,351 (98.5%) |

| Non-Caucasian | 20 (1.5%) |

| Smoking | |

| Former smokingd | 326 (23.6%) |

| Current smokingd | 280 (20.3%) |

| Postmenopausal status | 1,009 (72.2%) |

| Hormone suppletione | 88 (6.4%) |

| Previous gynaecological surgery | |

| Prolapse surgeryh | 103 (7.4%) |

| Hysterectomyi | 234 (16.9%) |

| Incontinence surgeryj | 47 (3.4%) |

Data are presented as number of women (percentage)

aData on 16 women are missing

bData on 33 women are missing

cData on 26 women are missing

dData on 15 women are missing

eData on 30 women are missing

fData on 25 women are missing

gData on 18 women are missing

hData on 13 women are missing

iData on 14 women are missing

jData on 15 women are missing

Table 2.

Prevalence of overactive bladder symptoms and any OAB symptoms per age groupa

| Frequencyb | Urgencyc | Urge incontinenced | Any of the OAB symptoms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45–55 | 162 (25.3%) | 193 (30.9%) | 178 (27.7%) | 298 (46.1%) |

| 56–65 | 121 (28.4%) | 141 (33.7%) | 116 (26.9%) | 200 (46.2%) |

| 66–75 | 80 (35.9%) | 92 (40.5%) | 79 (35.0%) | 126 (54.5%) |

| 76–85 | 24 (37.5%) | 33 (54.1%) | 32 (48.5%) | 42 (63.6%) |

| Overall | 393 (28.7%) | 463 (34.4%) | 411 (29.8%) | 677 (48.6%) |

Data are presented as number of women (percentage)

aData on age category on 16 women are missing

bData on frequency on 28 women are missing

cData on urgency on 52 women are missing

dData on urge incontinence on 16 women are missing

Table 3.

Prevalence of prolapse symptomse in women with symptoms of OAB

| Prolapse symptoms | No prolapse symptoms | P a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequencyb | 66 (41.8%) | 320 (26.9%) | 0.000 |

| Urgencyc | 77 (49.7%) | 379 (32.4%) | 0.000 |

| Urge incontinenced | 64 (40.3%) | 340 (28.3%) | 0.003 |

| Any of the OAB symptomse | 84 (69.4%) | 588 (46.6%) | 0.000 |

Data are presented as number of women (percentage)

a P value using chi-square test to compare the difference between women with versus without prolapse symptoms.

bData on 28 women are missing

cData on 52 women are missing

dData on 16 women are missing

eData on four women are missing

fData on prolapse symptoms on 24 women are missing

In Table 4, the various possible risk factors including the presence of POP symptoms for the presence of OAB symptoms are presented in a univariate logistic regression model.

Table 4.

Factors of the univariate logistic regression analysis on the various OAB symptoms

| Frequency OR (95% CI) | Urgency OR (95% CI) | Urge incontinence OR (95% CI) | Any OAB OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)a | 45–55 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 56–65 | 1.2 (0.9, 1.5) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.5) | 1.0 (0.7,1.3) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.3) | |

| 66–75 | 1.7 (1.2, 2.3) | 1.5 (1.1, 2.1) | 1.4 (1.0, 1.9) | 1.4 (1.0, 1.9) | |

| 76–85 | 1.8 (1.0, 3.0) | 2.6 (1.5, 4.5) | 2.5 (1.5, 4.1) | 2.0 (1.2, 3.5) | |

| Parity | ≤2 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| >2 | 1.3 (1.0, 1.7) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.3) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.3) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.5) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)b | <20 | 0.7 (0.3,1.5) | 0.4 (0.2, 1.0) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.5) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.0) |

| 20–25 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| 25–30 | 1.6 (1.3, 2.1) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.7) | 1.5 (1.1, 1.9) | 1.4 (1.1, 1.7) | |

| ≥30 | 2.0 (1.4, 2.8) | 2.2 (1.6, 3.1) | 2.2 (1.6, 3.1) | 2.3 (1.7, 3.2) | |

| Smoking | |||||

| Former smokingc | Yes | 1.3 (1.0, 1.8) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.6) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.4) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.4) |

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Current smokingc | Yes | 1.0 (0.8,1.4) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.7) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.7) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.6) |

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Postmenopausal status | Yes | 1.5 (1.2, 2.0) | 1.6 (1.2, 2.0) | 1.4 (1.1, 1.8) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.7) |

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Hormonal suppletion therapye | Yes | 1.2 (0.7, 1.9) | 1.2 (0.7, 1.8) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.2) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.4) |

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Previous gynaecological surgery | |||||

| Prolapse surgeryd | Yes | 2.5 (1.7, 3.8) | 2.6 (1.7, 3.9) | 1.9 (1.3, 2.9) | 2.9 (1.9, 4.6) |

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Hysterectomyh | Yes | 1.5 (1.1, 2.1) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.7) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.8) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.7) |

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Incontinence surgeryc | Yes | 3.5 (1.9, 6.5) | 3.4 (1.9, 6.3) | 4.3 (2.3, 8.0) | 6.5 (2.9, 14.5) |

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Prolapse symptomsi | Yes | 2.0 (1.4, 2.7) | 2.1 (1.5, 2.9) | 1.7(1.2, 2.4) | 2.6 (1.7, 3.9) |

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

All values with P < 0.05 are illustrated in bold

Ref: reference

aData on 16 women are missing

bData on 33 women are missing

cData on 15 women are missing

dData on 13 women are missing

eData on 30 women are missing

fData on 25 women are missing

gData on 18 women are missing

hData on 14 women are missing

iData on 24 women are missing

The OR shows the chance of the presence of OAB symptoms. An OR >1 indicates that the factor is positively correlated with the outcome variable; an OR <1 means that the factor indicates a negative correlation.

Table 5 shows the multivariate analysis of the OAB symptoms where all factors of the univariate analysis with a P < 0.3 are taken into account.

Table 5.

Risk factors on OAB symptoms after multivariate regression analysis

| Frequency OR (95% CI) | Urgency OR (95% CI) | Urge incontinence OR (95% CI) | Any OAB OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)a | 45–55 | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| 56–65 | 1.0 (0.8, 1.4) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.1) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.2) | ||

| 66–75 | 1.4 (1.0, 2.0) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.8) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.8) | ||

| 76–85 | 2.7 (1.5, 4.9) | 2.2 (1.3, 3.8) | 2.1 (1.2, 3.7) | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2)b | <20 | 0.7 (0.3, 1.6) | 0.4 (0.2, 0.9) | 0.7 (0.3, 1.5) | 0.5 (0.3, 1.0) |

| 20–25 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| 25–30 | 1.5 (1.1, 2.0) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.6) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.8) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.6) | |

| ≥30 | 1.7 (1.2, 2.4) | 2.2 (1.5, 3.1) | 2.0 (1.4, 2.9) | 2.2((1.5, 3.1) | |

| Smoking | |||||

| Smoking in the pastc | Yes | 1.4 (1.1, 1.9) | |||

| No | Ref | ||||

| Current smokingc | Yes | 1.7 (1.2, 2.3) | 1.4 (1.0, 1.8) | ||

| No | Ref | Ref | |||

| Postmenopausal status | Yes | 1.3 (1.0, 1.8) | |||

| No | Ref | ||||

| Previous gynaecological surgery | |||||

| Prolapse surgeryd | Yes | 2.3 (1.4, 3.6) | |||

| No | Ref | ||||

| Incontinence surgerye | Yes | 2.9 (1.5, 5.5) | 4.3 (2.3, 8.2) | 6.7 (2.8, 16.3) | |

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||

| Prolapse symptomsf | Yes | 2.4 (1.6, 3.5) | 2.2 (1.4, 3.3) | 1.8 (1.2, 2.6) | 2.3 (1.5, 3.5) |

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Variance explained by the modelg | 5.8% | 8.8% | 6.6% | 9.1% | |

OR odds rario, Ref reference

aData on 16 women are missing

bData on 33 women are missing

cData on 15 women are missing

dData on 13 women are missing

eData on 18 women are missing

fData on 24 women are missing

gNagelkerke R 2

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we looked at the prevalence of OAB symptoms and specifically the relationship between OAB symptoms and POP symptoms. We found a prevalence of urgency, frequency and urge urinary incontinence of 34%, 29% and 30%, respectively. The prevalence for any OAB symptoms was 49%. This is comparable with other studies, where a prevalence of 16.8–49% was found in women [3, 8]. POP symptoms were present in 11.4%, which is comparable with other studies where a prevalence of 4–30% was found [9–11].

Risk factors

This study found POP symptoms to be an independent risk factor for OAB symptoms. The sparse cross-sectional studies who mentioned a relationship between POP symptoms and OAB, showed a higher prevalence of OAB symptoms with POP symptoms than without POP symptoms (!) [5] but were not controlled for other risk factors. The same relationship between POP and OAB is found in hospital based studies, the prevalence of OAB symptoms is greater in patients with POP than without POP [5]. However, by the nature of these epidemiological studies a causal relationship cannot be established. There are many possible theories regarding the pathophysiology of OAB in relation to POP and it is likely that bladder obstruction plays an important role [5]. Nevertheless, several other mechanisms might be considered. The pathophysiological relationship between OAB and POP needs to be studied further. Important clinical implication of the relationship between POP and OAB is that treatment of POP could give an improvement in OAB symptoms. This is consistent with the finding in a recent review [5].

Another important risk factor for OAB symptoms was surgery for urinary incontinence in the past. Many studies have shown a relationship between continence surgery and OAB symptoms where the prevalence of de novo OAB varied between 15% and 29% on the short term (1–3 months postoperatively) [12, 13] and 0–30% on the long term [12–14]. As in other studies, we found the prevalence of OAB symptoms increased with advancing age [3, 8].

Overweight (body mass index [BMI] greater then 30) was another independent risk factor for OAB symptoms. This is consistent with other studies, who found the same relationship [15–19]. The study of Cheung found a similar OR for overweight [15], where the study of Lawrence found a higher OR (2.73) [18]. On the other hand, Choo et al. [16] found that BMI was only a predictor for OAB dry (urgency with or without frequency or nocturia), but not for OAB wet (urgency with urge incontinence, with or without frequency or nocturia).

Another factor for achieving urgency was smoking. Other studies are not conclusive about the role of smoking in OAB [17, 20, 21]. The study of Bradley et al. [20] found no relation between current smoking and urinary symptoms, while a large cross-sectional study showed that current and former smoking was associated with urgency [21]. One study found that current smokers were 1.44 time more likely to develop OAB, and the increased risk for former smokers was nearly significant [17]. The induction of OAB in smoking could be related to an anti-oestrogenic hormonal effect on the bladder and uretra [22] and a nicotine induced phasic contraction of the detrusor muscle [23].

Postmenopausal status was a risk factor for the symptom frequency in our study. This is consistent with another study which found postmenopausal status to be a predictor for OAB symptoms [24]. This can be explained because oestrogen has an important role in the urogenital tract through oestrogen receptors in urethra, bladder and pelvic floor [25], where deficiency causes atrophic changes [26], which is associated with OAB symptoms. Reversal of the atrophy by oestrogen treatment can have a positive influence on OAB symptoms [27].

Surprisingly, we found previous prolapse surgery to be a predictor for the symptom urgency, this in contrast to practically all studies that showed an improvement of OAB symptoms after prolapse surgery [5]. A possible explanation for this finding is that women after prolapse surgery achieved de novo urgency, as was found in 5% of the patients in one study [28].

Strengths and weaknesses

The strong point about this study is that it is a large cross-sectional study in a homogenic female population, which made multivariate analysis possible; as a result, however, genetic and racial factors could not be included, which is also an inherent weakness of the design.

Another weakness of this study is that not all factors of influence on OAB are included, such as food and beverages (coffee and alcoholic consumption) and the use of OAB therapies (bladder training and pharmacotherapy).

Conclusion

In this study, we found a prevalence of urgency of 34%, as the core symptom of the OAB spectrum, and of any OAB symptoms of 49%. POP symptoms are an independent risk factor for OAB symptoms. Other risk factors are continence surgery in the past, age above 75, overweight and smoking.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Digesu GA, Chaliha C, Salvatore S, Hutchings A, Khullar V. The relationship of vaginal prolapse severity to symptoms and quality of life. BJOG. 2005;112(7):971–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89(4):501–506. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Temml C, Heidler S, Ponholzer A, Madersbacher S. Prevalence of the overactive bladder syndrome by applying the International Continence Society definition. Eur Urol. 2005;48(4):622–627. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, Griffiths D, Rosier P, Ulmsten U, van KP, Victor A, Wein A. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21(2):167–178. doi: 10.1002/nau.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Boer TA, Salvatore S, Cardozo L, Chapple C, Kelleher C, van Kerrebroeck P, Kirby MG, Koelbl H, Espuna-Pons M, Milsom I, Tubaro A, Wagg A, Vierhout ME. Pelvic organ prolapse and overactive bladder. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29(1):30–39. doi: 10.1002/nau.20858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slieker-ten Hove MC, Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Eijkemans MJ, Steegers-Theunissen RP, Burger CW, Vierhout ME. Symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse and possible risk factors in a general population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(2):184–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uebersax JS, Wyman JF, Shumaker SA, McClish DK, Fantl JA. Short forms to assess life quality and symptom distress for urinary incontinence in women: the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire and the Urogenital Distress Inventory. Continence Program for Women Research Group. Neurourol Urodyn. 1995;14(2):131–139. doi: 10.1002/nau.1930140206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lapitan MC, Chye PL. The epidemiology of overactive bladder among females in Asia: a questionnaire survey. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12(4):226–231. doi: 10.1007/s001920170043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bump RC, Norton PA. Epidemiology and natural history of pelvic floor dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1998;25(4):723–746. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8545(05)70039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eva UF, Gun W, Preben K. Prevalence of urinary and fecal incontinence and symptoms of genital prolapse in women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(3):280–286. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2003.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samuelsson EC, Victor FT, Tibblin G, Svardsudd KF. Signs of genital prolapse in a Swedish population of women 20 to 59 years of age and possible related factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180(2 Pt 1):299–305. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abouassaly R, Steinberg JR, Lemieux M, Marois C, Gilchrist LI, Bourque JL, Tu lM, Corcos J. Complications of tension-free vaginal tape surgery: a multi-institutional review. BJU Int. 2004;94(1):110–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.04910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tellez Martinez-Fornes M, Fernandez PC, Fouz LC, Fernandez LC, Borrego HJ. A three year follow-up of a prospective open randomized trial to compare tension-free vaginal tape with Burch colposuspension for treatment of female stress urinary incontinence. Actas Urol Esp. 2009;33(10):1088–1096. doi: 10.4321/S0210-48062009001000010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmgren C, Nilsson S, Lanner L, Hellberg D. Frequency of de novo urgency in 463 women who had undergone the tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedure for genuine stress urinary incontinence—a long-term follow-up. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;132(1):121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheung WW, Khan NH, Choi KK, Bluth MH, Vincent MT. Prevalence, evaluation and management of overactive bladder in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-10-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choo MS, Ku JH, Lee JB, Lee DH, Kim JC, Kim HJ, Lee JJ, Park WH. Cross-cultural differences for adapting overactive bladder symptoms: results of an epidemiologic survey in Korea. World J Urol. 2007;25(5):505–511. doi: 10.1007/s00345-007-0183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dallosso HM, McGrother CW, Matthews RJ, Donaldson MM. The association of diet and other lifestyle factors with overactive bladder and stress incontinence: a longitudinal study in women. BJU Int. 2003;92(1):69–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410X.2003.04271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawrence JM, Lukacz ES, Nager CW, Hsu JW, Luber KM. Prevalence and co-occurrence of pelvic floor disorders in community-dwelling women. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(3):678–685. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181660c1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teleman PM, Lidfeldt J, Nerbrand C, Samsioe G, Mattiasson A. Overactive bladder: prevalence, risk factors and relation to stress incontinence in middle-aged women. BJOG. 2004;111(6):600–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradley CS, Kennedy CM, Nygaard IE. Pelvic floor symptoms and lifestyle factors in older women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2005;14(2):128–136. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nuotio M, Jylha M, Koivisto AM, Tammela TL. Association of smoking with urgency in older people. Eur Urol. 2001;40(2):206–212. doi: 10.1159/000049774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baron JA. Smoking and estrogen-related disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;119(1):9–22. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hisayama T, Shinkai M, Takayanagi I, Toyoda T. Mechanism of action of nicotine in isolated urinary bladder of guinea-pig. Br J Pharmacol. 1988;95(2):465–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11667.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang W, Song Y, He X, Huang H, Xu B, Song J. Prevalence and risk factors of overactive bladder syndrome in Fuzhou Chinese women. Neurourol Urodyn. 2006;25(7):717–721. doi: 10.1002/nau.20293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iosif CS, Batra S, Ek A, Astedt B. Estrogen receptors in the human female lower uninary tract. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;141(7):817–820. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(81)90710-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Versi E, Harvey MA, Cardozo L, Brincat M, Studd JW. Urogenital prolapse and atrophy at menopause: a prevalence study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12(2):107–110. doi: 10.1007/s001920170074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson D, Cardozo L. New drug treatments for urinary incontinence. Maturitas. 2010;65(4):340–347. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Boer TA, Kluivers KB, Withagen MI, Milani AL, Vierhout ME. Predictive factors for overactive bladder symptoms after pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2010;21(9):1143–1149. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1152-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]