Abstract

The authors describe a case of gastric volvulus, which is a rare cause of gastric outlet obstruction. An 85-year-old man presented with nausea, vomiting, and epigastric pain. Admission abdominal radiograph demonstrated a grossly distended stomach with air-fluid levels. Multiple attempts at nasogastric tube placement failed. Endoscopy revealed a fluid-filled, tortuous stomach with a paraesophageal hernia, and the operator was unable to locate or pass the scope through the pylorus. Traditionally Borchardt's triad is believed to be diagnostic for acute gastric volvulus and consists of unproductive retching, epigastric pain and distention, and the inability to pass a nasogastric tube. The authors propose that the following features on endoscopy are highly suggestive of the most common type of volvulus (organoaxial): tortuous stomach, paraesophageal hernia, and inability to locate or pass the scope through the pylorus.

Introduction

Gastric volvulus is rare and its incidence is not well defined in the literature. It is rotation of the stomach more than 180 degrees creating a closed loop obstruction.1 This condition can be primary or secondary, with secondary volvulus due to paraesophageal hernia being more common. Secondary volvuli in the adult are most commonly due to paraesophageal hernias and the peak incidence occurs in the fifth decade of life.1–4 Approximately 20% of gastric volvulus cases occur in infants under 1 year of age and are often secondary to congenital diaphragmatic defects.2

There are three anatomic types: organoaxial, mesenteroaxial, and a combination of both. Organoaxial volvulus is caused by rotation along the longitudinal cardiopyloric axis.2 This is the most common type, accounting for two-thirds of cases, and is usually associated with diaphragmatic defects, most commonly a paraesophageal hernia. Organoaxial volvulus is far more common than mesenteroaxial volvulus and a combination of both. Mesenteroaxial volvulus occurs when torsion occurs around the transverse axis of the stomach.2 Distinction between types is not crucial as the classification is more descriptive than prognostic.1

This condition may present as an acute abdominal emergency or a chronic cause of upper abdominal discomfort. Borchardt's triad is believed to be diagnostic for acute gastric volvulus and consists of unproductive retching, epigastric pain and distention, and the inability to pass a nasogastric tube.5 Carter et al suggest three additional findings that may be very suggestive of gastric volvulus: minimal abdominal findings when the stomach is in the thorax; a gas-filled viscus in the lower chest or upper abdomen on chest radiograph, especially when associated with a paraesophageal hernia; and obstruction at the site of the volvulus shown by upper gastrointestinal (GI) series.6 Mortality from acute gastric volvulus has been reported to be as high as 30–50%.7 As a result, quick recognition and prompt surgical correction remain key in therapy for acute gastric volvulus.2

Thus, although a rare diagnosis, primary care providers and emergency room physicians should be aware of the tell-tale signs of gastric volvulus in a patient with a gastric outlet obstruction. In addition, endoscopists should be cognizant of endoscopic features that are suggestive of this diagnosis. Based on our experience with the case described below we propose that the following features on endoscopy are highly suggestive of the most common type of volvulus (organoaxial): tortuous stomach, paraesophageal hernia, and inability to locate or pass the scope through the pylorus.

Case Report

An 85-year-old man presented with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain ten to fifteen minutes after eating. Past medical history included coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure (ejection fraction of 15%), automated implantable cardioverter-defibrillator placement, and chronic kidney disease. Review of systems revealed a forty pound weight loss and early satiety over the past six months. Physical exam was significant for a firm, distended abdomen, decreased bowel sounds, and epigastric tenderness. Admission abdominal film demonstrated a grossly distended stomach with air-fluid levels (Figure 1). Admission laboratories were unchanged from baseline. CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis confirmed stomach distention with air-fluid levels consistent with gastric outlet obstruction. There was no obstructing mass or stone noted on CT scan.

Figure 1.

Admission KUB revealing a grossly distended stomach with air fluid levels, typical of gastric volvulus.

The patient was made NPO, and two attempts at nasogastric tube placement failed. Gastroenterology was consulted and placed a nasogastric tube endoscopically over a wire. Endoscopy revealed a fluid-filled, tortuous stomach with a paraesophageal hernia (Figure 2). The operator was unable to locate or pass the scope through the pylorus. There were multiple necrotic/superficial ulcerative lesions (Figure 3) and biopsy revealed acutely inflamed gastric mucosa with focal, necrotic luminal material. An upper GI series was consistent with gastric volvulus and a paraesophageal hernia of the duodenum. General surgery scheduled the patient for laparoscopic repair and he was placed on total parenteral nutrition. The evening prior to surgery he developed a non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction, with echocardiogram revealing marked right wall motion abnormality with posterior wall akinesis. He was transferred to the ICU and was medically managed, but developed a hemodynamically significant upper GI bleed. The patient and his family decided to pursue hospice care given his serious condition.

Figure 2.

Upper GI Endoscopy in retroflexion view revealing a paraesophageal hernia and retained stomach contents.

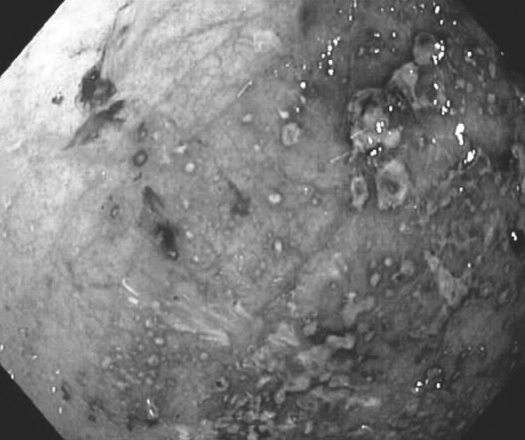

Figure 3.

Upper GI Endoscopy revealing diffuse gastritis and necrotic lesions.

Discussion

Gastric volvulus may present as an acute abdominal emergency or a chronic cause of upper abdominal discomfort. Borchardt's triad is believed to be diagnostic for acute gastric volvulus and consists of unproductive retching, epigastric pain and distention, and the inability to pass a nasogastric tube.5 Acute volvulus can cause gastric infarction leading to GI hemorrhage, acute cardiopulmonary distress, or shock.1 Chronic volvulus is characterized by upper abdominal discomfort similar to peptic ulcer disease, gastritis, cholecystitis, chronic pancreatitis, or angina pectoris.9 Chronic volvulus can spontaneously reduce by the time of evaluation, leading to delay in diagnosis and treatment.9

Radiographic findings include herniation of the stomach above the diaphragm, with differential air fluid levels.8 Upper GI series is usually diagnostic and can define the anatomical type of volvulus. CT scan can help confirm the rotation of the herniated stomach and the transition point.8 Endoscopic diagnosis can reveal a tortuous appearance of the stomach and difficulty or inability to reach the pylorus.9

Acute volvulus requires immediate surgery to prevent vascular compromise. The preferred procedure is anterior gastropexy in which the greater curve of the stomach is fixed to the undersurface of the anterior abdominal wall.1 Endoscopic reduction has been reported but does not address the underlying pathology that predisposes to torsion of the stomach.1

This case illustrates the importance of primary care and emergency room physicians in being aware of the utility of Borchardt's triad in the diagnosis of gastric volvulus. In addition, this case emphasizes the role of upper endoscopy in the diagnosis of gastric volvulus. This entity was not part of our initial differential diagnosis until we performed endoscopy. Other authors have noted that endoscopic diagnosis can reveal a tortuous appearance of the stomach and difficulty or inability to reach the pylorus.1,9 Based on our experience with this case, the following features on endoscopy are highly suggestive of the most common type of gastric volvulus (organoaxial): tortuous stomach, presence of a paraesophageal hernia, and inability to locate or pass the scope through the pylorus. If paraesophageal hernia is absent, we cannot definitively state mesenteroaxial volvulus alone or in combination with organoaxial volvulus cannot be present. Thus, this work should serve as a hypothesis generating paper and such criteria would need further study for validation at a large center that sees gastric volvulus with more frequency.

Footnotes

The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the US Government.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no disclosures.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

References

- 1.Wasselle JA, Norman J. Acute Gastric Volvulus: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88(10):1780–1784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Godshall D, Mossallam U, Rosenbaum R. Gastric volvulus: case report and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 1999 Sep–Oct;17(5):837–840. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(99)00092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanner CN. Chronic and recurrent volvulus of the stomach. Am J Surg. 1968;115:505–515. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(68)90194-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singleton AC. Chronic gastric volvulus. Radiology. 1940;34:53–61. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson JA, Thompson AR. Gastric Volvulus and the Upside-down Stomach. J Miss State Med Assoc. 1994;35(1):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter R, Brewer LA, Hinshaw DB. Acute gastric volvulus. A study of 25 cases. Am J Surg. 1980;140:99–104. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(80)90424-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith RJ. Volvulus of the stomach. JAMA. 1983;75:393–396. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peterson CM, Anderson JS, Hara AK, Carenza JW, Menias CO. Volvulus of the Gastrointestinal Tract: Appearances at Multi-modality Imaging. Radiographics. 2009;29(5):1281–1293. doi: 10.1148/rg.295095011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schaefer DC, Nikoomenesh P, Moore C. Gastric Volvulus: An Old Disease Process with some new twists. Gastroenterologist. 1997;5(1):41–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]