Abstract

Motivation: Deciphering the regulatory and developmental mechanisms for multicellular organisms requires detailed knowledge of gene interactions and gene expressions. The availability of large datasets with both spatial and ontological annotation of the spatio-temporal patterns of gene expression in mouse embryo provides a powerful resource to discover the biological function of embryo organization. Ontological annotation of gene expressions consists of labelling images with terms from the anatomy ontology for mouse development. If the spatial genes of an anatomical component are expressed in an image, the image is then tagged with a term of that anatomical component. The current annotation is done manually by domain experts, which is both time consuming and costly. In addition, the level of detail is variable, and inevitably errors arise from the tedious nature of the task. In this article, we present a new method to automatically identify and annotate gene expression patterns in the mouse embryo with anatomical terms.

Results: The method takes images from in situ hybridization studies and the ontology for the developing mouse embryo, it then combines machine learning and image processing techniques to produce classifiers that automatically identify and annotate gene expression patterns in these images. We evaluate our method on image data from the EURExpress study, where we use it to automatically classify nine anatomical terms: humerus, handplate, fibula, tibia, femur, ribs, petrous part, scapula and head mesenchyme. The accuracy of our method lies between 70% and 80% with few exceptions. We show that other known methods have lower classification performance than ours. We have investigated the images misclassified by our method and found several cases where the original annotation was not correct. This shows our method is robust against this kind of noise.

Availability: The annotation result and the experimental dataset in the article can be freely accessed at http://www2.docm.mmu.ac.uk/STAFF/L.Han/geneannotation/.

Contact: l.han@mmu.ac.uk

Supplementary Information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Understanding the role of expression of a given gene and interactions between genes in the developmental processes of multicellular organisms requires monitoring the gene expression levels and spatial distributions on a large scale. Two high-throughput methods have been widely used to curate gene expression at different developmental stages of organisms including: DNA microarrays (Brown and Botstein, 1999; Schena et al., 1995) and RNA in situ hybridization (ISH) (Christiansen et al., 2006; Eurexpress, 2009; Visel et al., 2002). DNA microarrays measure gene expression levels of a large number of genes for a tissue sample or cell, which can reflect the relative changes of gene expression level in each individual gene during time courses. However, it does not provide spatial gene expression patterns. RNA ISH uses specific gene probes to detect and visualize spatial–temporal information of particular target genes in tissues. It offers the possibility to construct a transcriptome-wide atlas of multicellular organisms that can provide spatial gene pattern information for comprehensive analysis of the gene interactions and developmental biological processes. The result of RNA ISH consists of images of sections of tissue stained to reveal the presence of gene expression patterns. To understand gene functions and interactions of genes in depth, we need to transform the raw image data into detailed knowledge. Annotation of gene expression patterns in the raw images from RNA ISH provides a powerful way to address this issue. The process of annotating gene expression pattern comprises the labelling of images with ontological terms corresponding to anatomical components. For every anatomical component that shows expression in the image, the image is labelled with that anatomical component using an hierarchically structured ontology that describes the developing mouse embryo.

Much effort has been devoted to the curation of gene expression patterns in the developmental biology. For example, the EUREXPress project (Eurexpress, 2009) has built a transcriptome-wide atlas for the developing mouse embryo established by RNA ISH; it has so far collected more than 18 000 genes at one development stage of wild-type murine embryos and has curated 4 TB of images. Some studies have been conducted on Drosophila gene expression patterns (Lecuyer et al., 2007; Tomancak et al., 2002, 2007), for instance, the research in Lecuyer et al. (2007) has produced 3375 genes for genome-wide analysis on Drosophila. Many other spatial gene expression patterns generated via RNA ISH such as FlyBase (Drysdale, 2008) and Mouse Atlas (Lein et al., 2006) provide rich information for genetics.

Currently, all annotations of spatial gene expression is hand curated by domain experts. With large amount of curated image data available already and a further increase in volume expected due to more automatic instruments for ISH, it is difficult and inefficient for domain experts to keep relying fully on manual annotation. Furthermore, the accuracy of annotation heavily relies on the consistency of domain experts. Therefore, it is crucial to develop an automatic method for the annotation of spatial gene expression patterns. Some existing studies have developed methods for annotating images from fruit fly (Grumbling et al., 2006; Harmon et al., 2007; Ji et al., 2008; Mace et al., 2010; Pan et al., 2006; Zhou and Peng, 2007) and adult mouse brain (Carson et al., 2005). These annotations have provided potential opportunities for further genetic analysis. However, to date, no attempt was made to automatic annotation of gene expressions for mouse embryos. In comparison with a fly embryo, the structure of an embryonic mouse in its later stages of development (Baldock et al., 2003; Christiansen et al., 2006) is more complicated and has many more anatomical components, for instance, the data curated by EURExpress project, used in our study, are all from 23 stage, a late stage in the developmental mouse embryo. The anatomical structure of the mouse embryo is complex and there are over 1500 anatomical features to be annotated.

In this article, we have developed and evaluated a method to automatically annotate images resulting from ISH experiments on mouse embryos performed in the EURExpress project (Eurexpress, 2009).

The main contribution of our study consists of the following aspects.

We have developed a method that combines machine learning and image processing. We use image processing to pre-process images and feed the result to a machine learning method to construct classification models for automatic annotation.

To cope with issues arisen in multi-anatomical components coexisting in images, we have designed a set of binary classifiers—one for each anatomical component. The main advantage is a strong extensibility of the framework. Given a dataset, if a new anatomical component to be annotated appears, we can create a new classifier and directly use it without the need to re-create previous classifiers. Consequently, the classification performance of existing classifiers will not be affected when new classifiers are added.

We evaluate our method on image data from the EURExpress-II study where we use it to automatically classify nine anatomical terms: humerus, handplate, fibula, tibia, femur, ribs, petrous part, scapula and head mesenchyme. The accuracy of our method lies between 70% and 80% with few exceptions. We show that other known methods perform far worse and have much more variability in their accuracy.

We have investigated the images misclassified by our method and found several cases where the original annotation was not correct. This shows our method is robust against this kind of noise.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. The problem domain is described in Section 2; Section 3 presents the method used in this proposed framework; Section 4 describes the evaluation of our method; Section 5 concludes and discuss our work.

2 PROBLEM CONCEPTUALIZATION

2.1 Data description and challenges

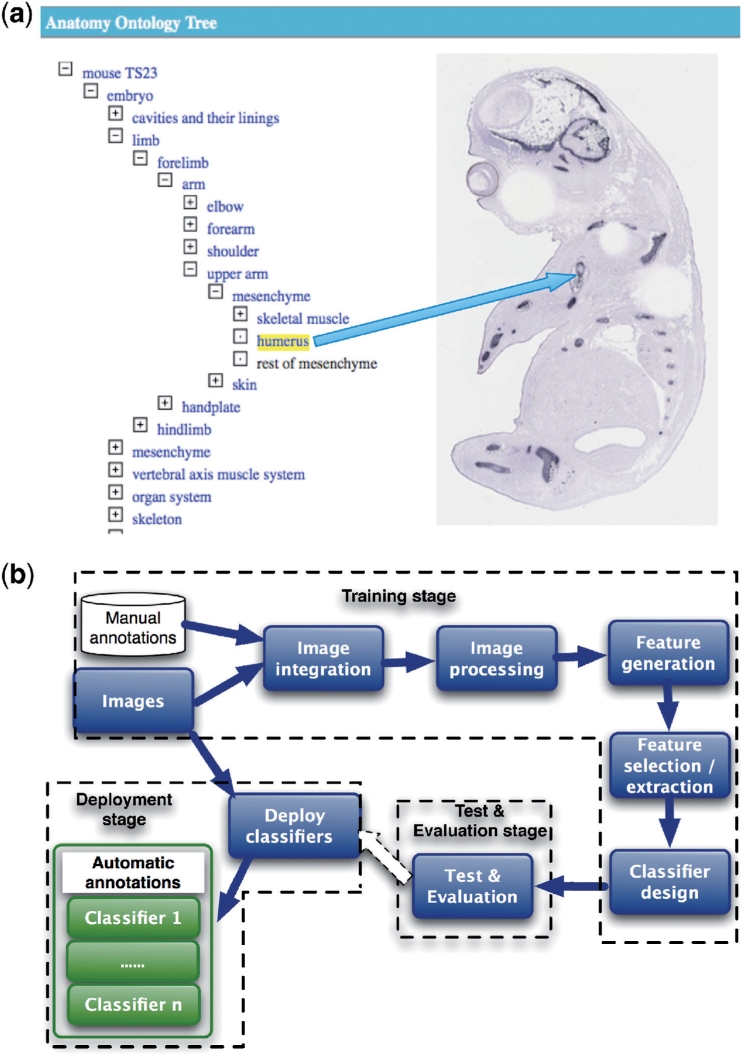

The data used in this article is from the EURExpress project (www.eurexpress.org). The EURExpress project aims to build a transcriptome-wide atlas for the developing mouse embryo established by RNA ISH. The project uses automated processes for ISH experiments on all genes of whole-mount mouse embryos at Theiler Stage 23. The result is many images of embryo sections that are stained to reveal where RNA is present, namely where genes are expressed in embryos. These images are then annotated by human curators. The annotation consists of 1500 terms representing anatomical components, which are used to label each image if and only if an image exhibits gene expression in the whole or part of that component. So far, 80% of images have been manually annotated by human curators. The goal is to automatically perform annotation of the remaining 20% and any new images with the correct terms. Currently, 85 824 images remain to be annotated. In other words, the input to our method is a set of image files and corresponding metadata. The output will be the identification of all anatomical components that exhibit gene expression patterns for each image. This is a typical pattern recognition task. As shown in Figure 1a, we need first to identify the features of ‘humerus’ in the embryo image and then annotate the image using ontology terms listed on the left side.

Fig. 1.

Formulation of automatic identification and annotation of spatial gene expression patterns. (a) An example of annotating an image using a term from the anatomy ontology for the developing mouse embryo. (b) A high-level overview of the method for automatic annotation of images from ISH studies.

Three major challenges must be overcome to automate the process of the annotation.

The images created from RNA ISH experiments include variations arising from natural variation in embryos and technical variation from processing and capturing material. The same anatomical components, therefore, may have variable shape, location and orientation.

Each image for a given gene will in general be annotated with multiple anatomical terms. This means features for multiple components coexist in the image, which increases the difficulty of discrimination. Hence, if components often exhibit gene expression in the same image, it will be hard to discriminate between the two components.

The number of images associated with a given anatomy terms is distributed unevenly. Some terms may be associated with many images, whereas others with only a few.

To address these challenges, we have developed a new method that combines image processing with machine learning techniques to automatically identify gene expressions in images, as shown in Figure 1b.

2.2 A high-level overview of the pattern recognition task

To automatically annotate images, the following three stages are required. At the training stage, the classification model has to be built, based on a training set of image datasets with human annotations. At the testing stage, the performance of the classification model has to be evaluated in terms of accuracy. Finally, when the performance is satisfactory, at the deployment stage the model has to be deployed to perform the classification of images without annotation.

The following subtasks are needed for the training stage: integration of images and annotations; image processing; feature generation; feature selection and extraction; and classifier design. These are shown in Figure 1b.

Image integration: before we can perform machine learning, we need to integrate data from different sources. The manual annotations are stored in a database and the images are located in a file system. The result of this integration process is a set of images with annotations.

Image processing: the width and height of images are variable. We apply median filtering and image rescaling to reduce image noise and rescale the images to a standard size. The output of this process is a set of standardized and de-noised images. These images can be represented as 2D arrays m × n.

Feature generation: after image pre-processing, we generate features that represent different gene expression patterns in images. We use a wavelet transform method to obtain features. The features again are represented as 2D arrays m × n.

Feature selection and extraction: due to the large number of features, the feature arrays must be reduced before we can construct a classifier. This can be done by either feature selection or feature extraction or a combination of both. Feature selection selects a subset of the most significant features for constructing classifiers. Feature extraction performs the transformation on the original features to achieve the dimensionality reduction and obtain a representative feature vectors for constructing classifiers.

Classifier design: the main task is to annotate images with the correct anatomy terms. As gene patterns in images will typically express in several anatomical components, we must construct classifier that can discriminate between patterns in different components. Here, we have formulated this multi-class problem as a two-class problem. Namely, we construct a set of binary classifiers where each classifier will aim to decide for one anatomical component, whether that component exhibits gene expression. In other words, the result of such a classifier is either ‘detected gene expression’ or ‘not detected’.

The test and evaluation stage will use the result from the training stage to validate the accuracy of classifiers. During this stage, k-fold cross-validation is used for evaluating the classification performance. With k-fold validation, the sample dataset is randomly split into k disjoint subsets. For each subset, we construct a classifier using the data in k − 1 subsets and then evaluate the classifier's performance on the data in the k-th subset. Thus, each record of the dataset is used once to evaluate the performance of a classifier. If 10-fold validation is used, we can build 10 classifiers each trained on 90% of the data and each evaluated on a different 10% of the data. This process is essential to prevent unlucky distributions of training and testing datasets and to prevent the overall classifier from overfitting its performance on one training set.

The deployment stage deals with the configuration on how classifiers are deployed, i.e. how classifiers are applied to automatically add annotation to images that have not been annotated before.

3 METHODS

We have adopted image processing and machine learning methods to facilitate the annotation task.

3.1 Image processing

We first obtain training datasets by integrating both images and manual annotations using a database SQL query to specify which images will be included. These images will be filtered and standardized to a uniform size suitable for the feature generation process. We use median filter to remove noise from images (Baxes, 1994). The median filter is a non-linear filter. Its advantage over the traditional linear filter is its ability to eliminate noise values with extremely large magnitudes. The median filter replace a pixel using the median of its neighbouring pixels' values.

Given a 2D image, the value of a pixel is represented as f0(m0, n0), a neighbourhood of f0 is represented as K and a pixel value in k is represented as f(m, n). The representation of a median filter can be expressed mathematically as,

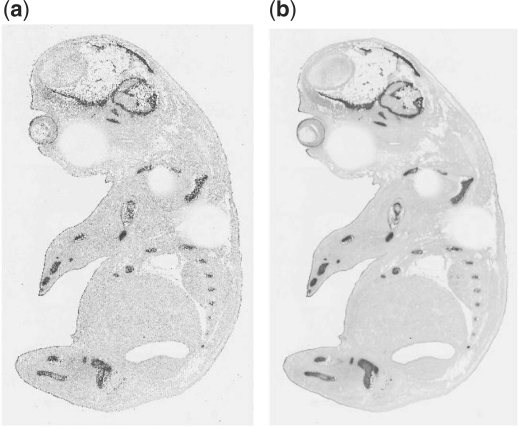

Figure 2a and b show the result of an image before and after the median filter. The filtered image is much smoother than the original image.

Fig. 2.

An example to show the effect of a mouse embryo image before and after the median filter. (a) Before using median filter. (b) After using median filter.

In addition to the median filter, we also standardize image sizes so that the images can be processed by the methods used in the feature generation step (e.g. where wavelet transform and matrix operations involved). Given an image, the output of the standardization is scale times of the original image size and all scaled images will have the same size as pre-specified; for instance, the dimension of an original image is 180 ×220. If the required image size is 200 × 368. The scaled image size will be 200 × 368.

3.2 Feature generation

To characterize multiple spatial gene expression patterns in embryo images, we use wavelet transforms to generate features. The wavelet transform is well known as a powerful tool for applications in signal and image processing (Mallat, 1999; Stollnitz et al., 1996). There are two major reasons for using the wavelet transform here. The wavelet transform provides a mathematical tool for the hierarchical decomposition of functions to obtain a projective decomposition of the data into different scales and therefore extract local information. In contrast, Fourier Transforms only provide global information in frequency domain. By using wavelet transforms, an image can be decomposed into different subimages at subbands (different resolution levels). As the resolution of the subimages are reduced, the computational complexity will be reduced.

In mathematics, the wavelet transform refers to the representation of a signal in terms of a finite length or fast decaying oscillating waveform (known as the mother wavelet). This waveform is scaled and translated to match the input signal. In formal terms, this representation is a wavelet series, which is the coordinate representation of a square integrable function with respect to a complete, orthonormal set of basis functions for the Hilbert space of square integrable functions. Wavelet transforms include continuous wavelet transform and discrete wavelet transform. In this case, the 2D discrete wavelet transform has been used to generate features from images.

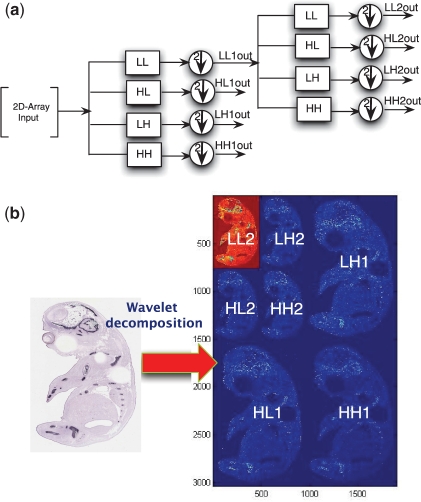

In fact, the wavelet transform of a signal can be represented as an input passing through a series of filters with down sampling to derive output signals based on scales (resolution levels). This is achieved using iterations. Figure 3a shows the filter representation using the wavelet transform on a 2D array input. LL is a low-low pass filter that is a coarser transform of the original 2D input and a circle with an arrow means down sampling by 2; HL is a high-low pass filter that transforms the input along the vertical direction; LH is a low-high pass filter that transforms the input along the horizontal direction; and HH is a high-high pass filter that transforms the input along the diagonal direction. After the first iteration of applying these filters into the input (called wavelet decomposition), the result of this wavelet transform will be LL1out, HL1out, LH1out, HH1out. In the second iteration, we continue performing wavelet transformation on LL1out and the output will be LL2out, HL2out, HL2out, HH2out. These steps can be continued, which leads to decomposition of the initial input signal into different subbands.

Fig. 3.

An example of the process and result of wavelet decomposition. (a) Wavelet decomposition on 2D-array. (b) Wavelet decomposition on an image.

Mathematically, for a signal f(x, y) with 2D array M × N, the wavelet transform is the result of applying filters at different resolution levels (e.g. LL1out, HL1out, LH1out, HH1out, LL2out, HL2out, etc.), which can be calculated as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where i=(H, V, D), Wϕ(j0, m, n) is LLout1 and Wψi(j, m, n), respectively, represents HL1out, LH1out and HH1out when the wavelet decomposition is performed along the vertical, horizontal and diagonal direction. j0 is a scale as start point. ϕ(j0, m, n) and ψj,m,n are wavelet basis functions. In this case, we use Daubecheis wavelet basis functions (db3) (Daubechies, 1992).

An example of a wavelet transform of an embryo image at the second resolution level is shown in Figure 3b. The image is decomposed into four subbands (subimages). The subbands LH1, HL1 and HH1 are the transformations of the image along horizontal, vertical and diagonal directions with the higher frequency component of the image, respectively. After applying filters, the wavelet transform of LL1 is further carried out for the second-level resolution as LL2, LH2, HL2 and HH2. If the resolution of the image is 3040 × 1900, the dimension of subimages are down sampled by a factor of 2 at the second resolution level and are, respectively, LL2 (760 × 475), LH2 (760 × 475), HL2 (760 × 475), HH (760 × 475), LH1 (1520 × 950), HL1 (1520 × 950) and HH1 (1520 × 950). The number of coefficients from the total wavelet transform—these are the features—for this image is 3040 × 1900 = 5776000.

3.3 Feature selection and extraction

Due to the large number of high-dimensional features generated in the previous subtask, it is necessary to select the most discriminating features. We use Fisher Ratio analysis (Duda and Hart, 1973) for feature selection and extraction. The Fisher Ratio finds a separation space to discriminate features of two classes by maximizing the difference between classes and minimizing differences within each class. For two classes, C1{x1,…, xi,…, xn} and C2{y1,…, yi,…, yn}, the Fisher Ratio is defined as the ratio of class-to-class variance to the variance of within classes. The Fisher Ratio can be represented as follows:

| (3) |

where m1,i represents the mean of samples at the i-th feature in C1, m2,i represents the mean of samples at the i-th feature in C2. v1,i represents the variance of samples at the i-th feature in C1. Similarly, v2,i represents the variance of samples at the i-th feature in C2.

3.4 Classifier construction

We construct a classifier for each anatomical component and formulate our multi-class problem as a two-class problem. Namely, for each anatomical component, e.g. a classifier, we create a training dataset that is divided into two classes; one class contains all the samples that exhibit spatial gene expression in part of the anatomical component and the other contains all the samples without any gene expression in that component. In this case, we use linear discriminant analysis (LDA) (Duda and Hart, 1973). For a given two-class problem (C1{x1,…, xi,…, xn} and C2{y1,…, yi,…, ym}), the linear discriminant function can be formulated as follows:

| (4) |

The goal is to find W (a weight vector) and w0 (a threshold) so that if f(X) > 0, then X is C1 and if f(X) < 0 then X is C2. The idea is to find a hyperplane that can separate these two classes. To achieve this, we need to maximize the target function denoted as follows:

| (5) |

where SW is called the within-class scatter matrix and SB is the between-class scatter matrix. They are defined, respectively, as follows:

| (6) |

where m1 is the mean of xi ∈ C1 and m2 is the mean of yi ∈ C2.

| (7) |

where S1 = ∑x∈C1(X − m1)(X − m1)T and S2 = ∑y∈C2(Y − m2)(Y − m2)T.

4 EXPERIMENTAL EVALUATION

4.1 Experimental setup and evaluation metrics

Currently, we have built up nine classifiers for nine gene expressions of anatomical components (humerus, handplate, fibula, tibia, femur, ribs, petrous part, scapula and head mesenchyme) and have evaluated our classifiers using 809 images.

We have used 10-fold cross-validation to validate the accuracy of our proposed method. The dataset (809 image samples) is randomly divided into 10 subsets. Nine subsets are formed as a training set and one is viewed as a test set. This process is then repeated 10 times with each subset used exactly once as the validation dataset. The classification is calculated based on the average accuracy across the 10-folds.

We adopt both ‘sensitivity’ and ‘specificity’ as evaluation metrics to measure the classification performance. If both of specificity and sensitivity are high, we can say the accuracy of classification is good. Sensitivity is the true positive rate that represents the proportion of actual positives (i.e. those images that have gene expression in the anatomical component) in the test dataset that are correctly predicted. Specificity is the true negative rate that represents the proportion of negatives (e.g. those images that do not have gene expression given the anatomical component) that are correctly predicted.

Table 1 shows the results of 10-fold validation for 9 anatomical components in terms of specificity and sensitivity as averaged over the 10-folds with a confidence interval of 95% around the average (in brackets). The confidence interval for specificity and sensitivity can be calculated as average ± confidence. The result clearly shows that the proposed method for automatic classification works well with the specificity and sensitivity between 70% and 80% for most components. The exceptions are ribs, where it is difficult to identify gene expression that is not present, and head mesenchyme, where it is difficult to identify gene expression that is present. We postulate that this could be a result of the particular shape and distributed nature of these anatomical components.

Table 1.

A comparison of accuracy of our proposed method with four well-known machine learning methods for classification on nine anatomical components

| Anatomic component | Our proposed method |

SVM |

LSVM |

ANN |

CNN |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sp | Se | Sp | Se | Sp | Se | Sp | Se | Sp | Se | |

| Humerus | 0.7872 (0.0418) | 0.7521 (0.0393) | 0.838 | 0.6667 | 0.4992 | 0.4949 | 0.8985 | 0.5101 | 0.9722 | 0.0707 |

| Handplate | 0.7927 (0.0299) | 0.6607 (0.0911) | 1.00 | 0.0263 | 0.6739 | 0.75 | 0.5744 | 0.5395 | 1 | 0 |

| Fibula | 0.7195 (0.0335) | 0.7192 (0.0732) | 0.9738 | 0.0744 | 0.7253 | 0.719 | 0.7922 | 0.562 | 1 | 0 |

| Tibia | 0.7435 (0.0534) | 0.7467 (0.084) | 0.9439 | 0.2667 | 0.7511 | 0.74 | 0.9044 | 0.5133 | 0.9954 | 0 |

| Femur | 0.7227 (0.0273) | 0.722 (0.0751) | 0.9726 | 0.2414 | 0.5613 | 0.6466 | 0.8802 | 0.4914 | 1 | 0 |

| Ribs | 0.7498 (0.0321) | 0.5512 (0.058) | 0.7939 | 0.5088 | 0.124 | 0.9018 | 0.7252 | 0.5649 | 0.7691 | 0.5228 |

| Petrous part | 0.7343 (0.0310) | 0.7897 (0.0558) | 0.9854 | 0.1129 | 0.2715 | 0.8629 | 0.8015 | 0.629 | 1 | 0 |

| Scapula | 0.707 (0.035) | 0.7889 (0.0863) | 0.9945 | 0.0588 | 0.7265 | 0.7529 | 0.8218 | 0.5647 | 1 | 0 |

| Head mesenchyme | 0.578 (0.0252) | 0.80 (0.08554) | 1.00 | 0.0143 | 0.3045 | 0.8571 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1 | 0 |

The sensitivity (Se) is the true positive rate. The specificity (Sp) is the true negative rate, with 95% confidence intervals reported in brackets for the results of our proposed method.

4.2 A comparative study with other machine learning methods

We have evaluated other well-known machine learning algorithms. These are Support Vector Machine (SVM) (Shawe-Taylor and Cristianini, 2000), Artificial Neural Networks (ANN ) (German and Gahegan, 1996) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) (Lawrence et al., 2002) and Lagrangian Support Vector Machines (LSVMs) (Mangasarian and Musicant, 2006).

SVM is a classification method that uses a maximum margin hyperplane from a set of hyperplanes in a high-dimensional space to separate two or more classes by distancing the plane from the closest data point of all classes. LSVM is a specific SVM based on an iterative approach with the aim to speed up training.

ANN is an Artificial Neural Network program that is inspired by the operation of biological neural networks. It provides a non-linear classification. The neural network processes samples one by one and compares the results calculated by the neural network with the known classification of samples. The errors are then fed back into the network in order to modify parameters for the next iteration until the output gets closer to the known correct classification of samples. There is another class called Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), which are often used to face recognition. They provide non-linear algorithms for feature extraction in hidden layers built into the ANN, which consider local receptive fields, shared weights and spatial subsampling to achieve a certain degree of shift and distortion invariance (Lawrence et al., 2002).

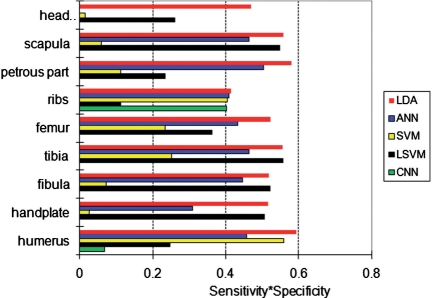

We have computed both the sensitivity and specificity when using SVM, LSVM, ANN and CNN to perform the patter recognition task. We have optimized the parameter settings for these algorithms and then have performed the same k-fold cross-validation as for our method. The results are shown in Table 1. When compared with results from our method, we conclude our method outperforms the other four methods as it provides the most consistent results across the anatomical components as well as the most balanced results between sensitivity and specificity. Note that it is easy to get a high sensitivity by classifying many images as positive, but this will lead to a low specificity. The results from SVM for handplate and head mesenchyme are a good example of this kind of unwanted behaviour. (Although both SVM and LDA are using hyperplanes to separate two classes, their performance can have a vast difference based on problem domains. This is because they adopt different optimal criteria to find that hyperplanes. With SVM, it is hard to reach convergence in the experiments.) Similarly, with CNN, we have worse classification performance, comparing with others. (It is also hard to reach convergence in the experiments.) The overall classification performance is compared in Figure 4 by multiplying the specificity and sensitivity results of each method.

Fig. 4.

The overall classification performance in terms of sensitivity × specificity (higher is better) of the five classification methods (LDA, SVM, LSVM, ANN and CNN) for each anatomical component.

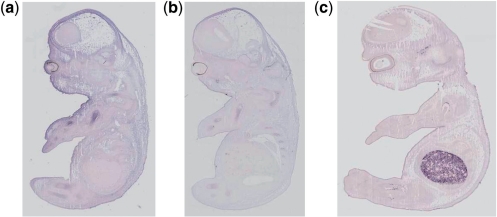

4.3 A further investigation into falsely classified images

Upon inspection of the images falsely classified in the test sets, either as false positives (i.e. classified as gene expression in an anatomical component while the manual curation states that no expression is present) or false negatives, we found that several images were erroneously annotated. In Figure 5, we discuss and show several examples where we explain the reasons for the erroneous annotations. This suggests that the results in Table 1 can be further improved by correcting the annotation of these images in the original dataset and then re-running the whole experiment. It also suggests that our technique is robust against the kind of noise arising from erroneous human annotation. Such noise is common in curated datasets often due to fatigue by the curators.

Fig. 5.

Several examples where, according to the data, our technique has falsely classified the images, but where, on closer inspection the human annotation is not consistent with the image. (a) Euxassay 010351, section 1: erroneous false positive for humerus—curator has annotated humerus on Sections 2 and 3, but missed expression on Section 1. (b) Euxassay 010262, section 1: erroneous false positive for humerus—has no annotation due to error of curator; expression clearly visible in several sections. (c) Euxassay 003591, Section 1: erroneous false negative for humerus—curator has annotated based on gene expression seen in other sections where none is found here.

5 CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

We have developed and evaluated a method for automatic identification and annotation of gene expression patterns in images of ISH studies on mouse embryos.

Our method has several important features. The automatic identification and annotation of gene expression patterns is based on a flexible combination of image processing and machine learning techniques and provides an efficient way for domain experts that handle large datasets. The method allows incremental construction of classifiers as we have formulated the multi-class problem (i.e. what anatomical components exhibit gene expression in an image?) as a two-class problem (i.e. in this image does a given anatomical component exhibit gene expression?). One classifier is related only to one anatomical component and its result is, therefore, independent from other classifiers.

We evaluate our method on image data from the EURExpress study where we use it to automatically classify nine anatomical terms: humerus, handplate, fibula, tibia, femur, ribs, petrous part, scapula and head mesenchyme. The accuracy of our method lies between 70% and 80% with few exceptions. We show that other known methods perform far worse and have much more variability in their accuracy, both across anatomical components and between their sensitivity (i.e. the ability to correctly classify images that contain gene expression) and specificity (i.e. the ability to correctly classify images that do not contain gene expression).

We have investigated the images misclassified by our method and found several cases where the original annotation was not correct. This shows our method is robust against this kind of noise. Moreover, it shows our method is useful not only for automatic annotation, but also to validate existing annotation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Jianguo Rao, Jeff Christiansen and Duncan Davidson at the MRC Human Genetics Unit, IGMM, for their useful input to our study. The authors would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers, who provided detailed and constructive comments on an earlier version of this article.

Funding: This work is supported by the ADMIRE project, which is funded by EU Framework Programme (7 FP7-ICT-215024). The authors acknowledge the support of Lalir Kumar and Mei Sze Lam of the EURExpress team (EU-FP6 funding) at the MRC Human Genetics Unit.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Baldock R., et al. Emap and emage: a framework for understanding spatially organised data. Neuroinformatics. 2003;1:309–325. doi: 10.1385/NI:1:4:309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxes G.A. Digital Image Processing: Principles and Applications. New York, NY, USA: Wiley; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brown P.O., Botstein D. Exploring the new world of the genome with DNA microarrays. Nat. Genet. 1999;21:33–37. doi: 10.1038/4462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson J.P., et al. A digital atlas to characterize the mouse brain transcriptome. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2005;1:0290–0296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen J.H., et al. Emage: a spatial database of gene expression patterns during mouse embryo development. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D637–D641. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daubechies I. Ten Lectures on Wavelets. PA, USA: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics Philadelphia (S.I.A.M.); 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Drysdale R. Flybase: a database for the Drosophila research community. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008;420:45–59. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-583-1_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duda R.O., Hart P.E. Pattern Classification and Scene Analysis. New York, NY, USA: Wiley-Blackwell; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Eurexpress (2009) Available at: http://www.eurexpress.org/ (last accessed date March 4, 2011) [Google Scholar]

- German G., Gahegan M. Neural network architectures for the classification of temporal image sequences. Comput. Geosci. 1996;22:969–979. [Google Scholar]

- Grumbling G., et al. Flybase: anatomical data, images and queries. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D485–D488. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon C.L., et al. Comparative analysis of spatial patterns of gene expression in Drosophila Melanogaster imaginal discs. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 2007;4453:533–547. [Google Scholar]

- Ji S., et al. Automated annotation of drosophila gene expression patterns using a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1881–1888. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence S., et al. Face recognition: a convolutional neural-network approach. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Spec. Iss. Neural Netw. Pattern Recognit. 2002;8:98–113. doi: 10.1109/72.554195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecuyer E., et al. Global analysis of MRNA localization reveals a prominent role in organizing cellular architecture and function. Cell. 2007;131:174–187. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lein E.S., et al. Genome-wide atlas of gene expression in the adult mouse brain. Nature. 2006;445 doi: 10.1038/nature05453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace D.L., et al. Extraction and comparison of gene expression patterns from 2D RNA in situ hybridization images. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:761–769. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallat S.G. A Wavelet Tour of Signal Processing. Burlington, MA, USA: Academic Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mangasarian O.L., Musicant D.R. Technical Report. USA: Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706; 2006. Lagrangian support vector machines. [Google Scholar]

- Pan J., et al. Proceedings of the 12th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. New York, NY, USA, Philadelphia, PA, USA: ACM; 2006. Automatic mining of fruit fly embryo images; pp. 693–698. [Google Scholar]

- Schena M., et al. Quantitative monitoring of gene expression patterns with a complementary dna microarray. Science. 1995;270:467–470. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shawe-Taylor J., Cristianini N. An Introduction to Support Vector Machines and other Kernel-Based Learning Methods. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stollnitz E., et al. Wavelets for Computer Graphics. San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, Inc.; 1996. 94104-3205, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Tomancak P., et al. Systematic determination of patterns of gene expression during drosophila embryogenesis. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-12-research0088. research0088.1–88.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomancak P., et al. Global analysis of patterns of gene expression during drosophila embryogenesis. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R145. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-7-r145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visel A., et al. A Practical Guide to Neuroscience Databases and Associated Tools. MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2002. A gene expression map of the mouse brain. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Peng H. Automatic recognition and annotation of gene expression patterns of fly embryos. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:589–596. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]