To the Editor: Free radicals induce oxidative stress when overproduced, leading to injury and dysfunction of vital organs. Oxidative stress has also been implicated in normal aging. The measurement of isoprostanes has been found to be a reliable marker of oxidative stress. Whether this is due to overproduction of free radicals or impaired antioxidant defenses remains to be established.

Isoprostanes are oxidation products that result from oxidative stress and are readily measured in plasma.1 They correlate highly with markers of inflammation, cytokines, and vasoconstrictive molecules. It was hypothesized that oxidative stress may be related to multi-organ failure in elderly people.

METHODS

Hospitalized patients aged 70 and older with life-threatening illness were recruited from the Geriatric Services at Vanderbilt University Hospital and Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Nashville campus. Subjects received standard medical care. After informed consent, blood samples (10 cm3) were collected twice weekly for the duration of hospitalization for a maximum of 4 weeks. The Vanderbilt and Veterans Affairs institutional review committees approved this study, and all subjects provided informed consent.

Levels of plasma F2-isoprostanes (F2-IsoP) were determined according to mass spectroscopy using methods previously reported.1,2 Subjects were assigned Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II scores3 after their clinical, laboratory, and historical data were reviewed. This scale has been shown to be an objective measure predictive of severity of illness and mortality in acutely ill patients.3–5

RESULTS

Sixty-three plasma samples from 29 subjects were collected between 2002 and 2005 and analyzed for F2-isoprostane levels. The normal F2-IsoP range in plasma is 29 to 41 pg/mL. Subject characteristics included mean age 77, APACHE II scores 13 to 28, and the following diagnoses: pneumonia (n = 9), congestive heart failure (n = 8), urinary infection with sepsis (n = 4), advanced cancer syndromes (n = 4), dehydration (n = 3) and psoas abscess (n = 1).

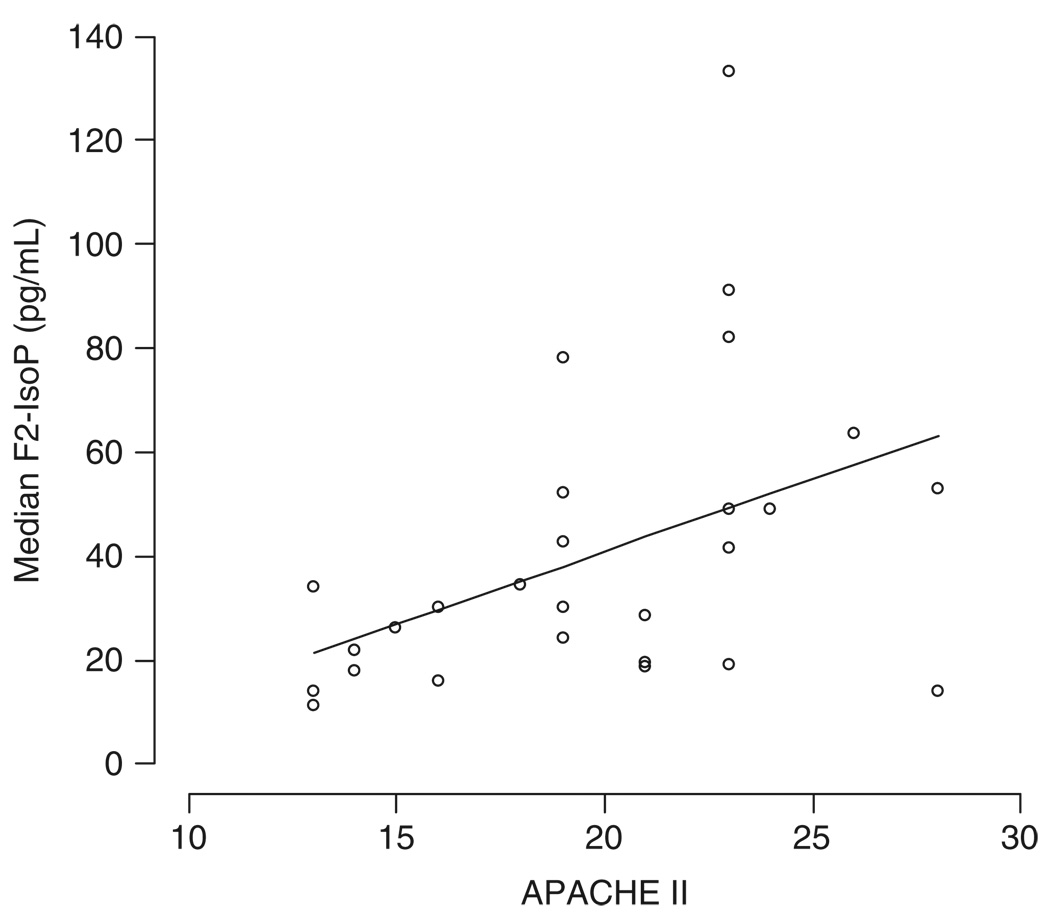

Descriptive statistics were computed using simple linear regression analysis of median F2-IsoP values using STATA 9.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) and R (www.r-project.org); the data are displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Plasma isoprostanes. Coefficient of determination = 0.37, P = .003.

CONCLUSION

These data support the hypothesis that the development of multi-organ failure in elderly people is related to oxidant stress resulting in overproduction of free radicals in various organs.

Aging is conceptualized as a pathophysiological phenomenon associated with disorganized homeostasis, including oxidative stress. Antioxidants have been shown to reduce peroxidase concentration in human endothelial cells.6 Older nematodes are less able to adapt to oxidative conditions,7 and lipoic acid administration reduces lipid peroxidation in older rats.8 l-carnitine has been found to reduce lipid peroxidase activity in brains of older rats,9 and carvedilol, possessing beta-antagonist and antioxidant properties, has been shown to reduce lipid peroxidation in cardiac tissue, resulting in improved cardiac function.10 These observations offer corroborative support for these findings and suggest possible pharmacological agents to counteract oxidant stress.

Limitations of the study include that subjects had many comorbidities and varying degrees of organ failure, variety of illnesses presented, and the narrow range of APACHE II scores, reflecting the severity of disease limitations inherent in a hospitalized, non-ICU population. Future study of patients in the intensive care unit with a defined illness such as sepsis is planned.

Contributor Information

James S. Powers, Tennessee Valley Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Nashville, TN, Department of Medicine, General Clinical Research Center, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN.

L. Jackson Roberts, II, Department of Medicine, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, General Clinical Research Center, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN.

Emily Tarvin, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN.

Nobuko Hongu, General Clinical Research Center, Nashville, TN, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN.

Leena Choi, General Clinical Research Center, Nashville, TN, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN.

Maciej Buchowski, General Clinical Research Center, Nashville, TN, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN.

REFERENCES

- 1.Morrow JD, Roberts LJ., II Mass spectrometric quantification of F2-isoprostanes in biological fluids and tissues as a measure of oxidant stress. Methods Enzymol. 1999;300:3–12. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)00106-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fessel JP, Porter NA, Moore KP, et al. Discovery of lipid peroxidation products formed in vivo with a substituted tetrahydrofuran ring (isofurans) that are favored by increased oxygen tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16713–16718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252649099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knaus W, Draper E, Wagner D, et al. Apache II: A severity of disease classification. Crit Care Med. 1981;13:818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berge K, Maiers D, Schreiner D, et al. Resource utilization and outcome in gravely ill intensive care patients with predicted in-hospital mortality rates of 95% or higher by APACHE III scores: The relationship with physician and family expectations. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2005:166–173. doi: 10.4065/80.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sirio C, Shepardson L, Rotondi A, et al. Community-wide assessment of intensive care outcomes using a physiologically based prognostic measure. Chest. 1999;115:793–801. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.3.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu D, Meydani M, Meydani S. Vitamin E increases production of vasodilator prostanoids in human aortic endothelial cells through opposing effects on cyclooxygenase-2 and phospholipase A2. J Nutr. 2005;135:1847–1853. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.8.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darr D, Fridovich I. Adaptation to oxidative stress in young, but not in mature or old, Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Rad Biol Med. 1995;18:195–201. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)00118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arivazhagan P, Panneerselvam S, Panneerselvam C. Effect of DL-alpha-lipoic acid on the status of lipid peroxidation and lipids in aged rats. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58A:B788–B791. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.9.b788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rani P, Panneerselvam C. Effect of L-carnitine on brain lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzymes in old rats. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57A:B134–B137. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.4.b134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakamura K, Kusano K, Nakamura Y, et al. Carvedilol decreases elevated oxidative stress in human failing myocardium. Circulation. 2002;105:2867–2871. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000018605.14470.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]