Abstract

Cardiomyocytes have a complex Ca2+ behavior and changes in this behavior may underlie certain disease states. Intracellular Ca2+ activity can be regulated by the phospholipase Cβ–Gαq pathway localized on the plasma membrane. The plasma membranes of cardiomycoytes are rich in caveolae domains organized by caveolin proteins. Caveolae may indirectly affect cell signals by entrapping and localizing specific proteins. Recently, we found that caveolin may specifically interact with activated Gαq, which could affect Ca2+ signals. Here, using fluorescence imaging and correlation techniques we show that Gαq-Gβγ subunits localize to caveolae in adult ventricular canine cardiomyoctyes. Carbachol stimulation releases Gβγ subunits from caveolae with a concurrent stabilization of activated Gαq by caveolin-3 (Cav3). These cells show oscillating Ca2+ waves that are not seen in neonatal cells that do not contain Cav3. Microinjection of a peptide that disrupts Cav3-Gαq association, but not a control peptide, extinguishes the waves. Furthermore, these waves are unchanged with rynaodine treatment, but not seen with treatment of a phospholipase C inhibitor, implying that Cav3-Gαq is responsible for this Ca2+ activity. Taken together, these studies show that caveolae play a direct and active role in regulating basal Ca2+ activity in cardiomyocytes.

Introduction

Small scale and local release of Ca2+ in cardiomyocytes, such as sparks and puffs, underlie the activity of larger scale Ca2+ signals (see (1,2)). Sparks and puffs are disrupted in diverse diseases such as diabetes and muscular dystrophy (see (1)). To date, the major focus of this Ca2+ activity has been the receptors that allow for intracellular Ca2+ release in the sarcoplasmic reticulum such as inositol 1,4,5, trisphophate (IP3) receptors and intracellular Ca2+ channels (IP3R) that open upon binding of IP3 (3,4). IP3R release of Ca2+ is propagated by ryanodine receptors (RyRs) that open upon Ca2+ binding. RyRs are the major source of Ca2+ -induced Ca2+ release in cardiac muscle cells (5). Release of Ca2+ ions due to RyRs are termed sparks, whereas those caused by IP3R are called puffs. To date, the factors that cause the initiation, propagation, and termination of Ca2+ sparks/puffs have not yet been fully characterized.

In this study, we focus on the control of Ca2+ puffs in cardiomyocytes resulting from IP3R activity. IP3 is generated through phospholipase C (PLC)—catalyzed hydrolysis of the signaling lipid, phosphatidylinositol 4,5 bisphosphate (PIP2). Of the major PLCs in cardiac tissue, the PLCβ family is activated by G-proteins that are coupled to hormonal and neural activity. All four known PLCβ isoenzymes are activated by the Gαq family of heterotrimeric G-proteins (6,7). Gαq is coupled to G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) that specifically bind ligands such as serotonin, dopamine, acetylcholine, bradykinin, and angiotensin (8,9). Additionally, two PLCβ isotypes, PLCβ2 and β3, are activated by Gβγ subunits that can potentially be released from all Gα families.

Although ligand binding to its specific GPCR produces rapid activation of PLCβ, signal termination is generally thought to be caused by receptor clustering and internalization, Gαq deactivation and/or depletion of PIP2. We have recently found a link between the time scale of signals generated through PLCβ/Gαq activation and the protein caveolin-1 (Cav1). Cav1 is the main structural component of membrane protein domains called caveolae. In many muscle cells such as cardiomyocytes, Cav3 is the major caveolin isoform (for reviews see (10–13)). Although the precise function of caveolae is unclear, these domains have been shown to play roles in vesicle trafficking and endocytosis. Additionally, caveolae have been postulated to act as scaffolds that organize signaling proteins on the plasma membrane surface.

There is evidence that many types of GPCRs and G-protein subunits localize to caveolae domains (14). Cell fractionation and immunofluorescence studies suggest that Gαq localizes to Cav1 domains (15,16). In vitro, we and others have detected a strong interaction between activated Gαq and Cav1 that is diminished when Gαq becomes deactivated (16,17). In contrast, Gβγ does not specifically bind to Cav1. Thus, the loss in affinity between Gαq and Gβγ that occurs upon activation, coupled with the increase in interaction between activated Gαq and Cav1, may promote diffusion of Gβγ subunits out of caveolae domains and prolong the recombination time of the G heterotrimer (16). In Fisher rat thyroid (FRT) cells stably transfected with Cav1, we have observed a prolonged Ca2+ response upon stimulation with a Gαq-coupled agonist, carbachol, but only when PLCβ was overexpressed. We postulated that this prolonged response was due to a combination of stabilization of activated Gαq by Cav1, and the release of Gβγ from caveolae domains, which allows for sustained PLCβ activation and results in a longer Ca2+ signal.

There is strong evidence that caveolae play a key role in the heart. Lisanti and co-workers found that Cav3 null mice develop progressive cardiomyopathy that is in some way connected to the ERK1/2 pathway (18). It is possible that the connection between the hyperactivation of cardiomyocytes in Cav3 null mice is linked ERK1/2 via the Gαq/Gβγ pathway. In this study, we explicitly show that Gβγ subunits are released from caveolae domains and that caveolae stabilize the activated state of Gαq. Of importance, the interaction between Cav3 and Gαq regulates Ca2+ puffs in adult cardiomyocytes. These studies connect caveolae regulation of Ca2+ signals with G-protein activity.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and transfection

Canine left ventricular myocytes, isolated from adult dogs, were a kind gift from Dr. Ira Cohen's laboratory (Stony Brook University, NY). The primary cardiac myocytes were plated on 10 μg/ml laminin-coated 35-mm glass bottom MatTek (Ashland, MA) dishes in KB buffer (K-reversal Tyrode buffer 35 mmol/L of HEPES, 140 mmol/L of KCl, 8 mmol/L of KHCO3, 2 mmol/L of MgCl2, and 0.4 mmol/L of KH2PO4, pH 7.5). The buffer was gradually changed to M199 medium supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum, 1% streptomycin, and 0.5% gentamicin and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were transfected with enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP)-Gβ1 and Gγ7 vectors (15 μg/106 cells in 60-mm dish) using calcium phosphate coprecipitation.

Rat neonatal cardiomyocytes were gifts from Dr. Emilia Entcheva (Stony Brook University). FRTwt and FRTcav+ cells, and the canine GFP-caveolin1 construct were gifts from Dr. Deborah Brown (Stony Brook University). Membrane fractions from FRTwt cells expressing GFP-caveolin1 were prepared as described (16).

Binding of eGFP-Cav1 and Alex546-Gαq using FRET

Harvested FRTcav+ GFP cells were washed twice with PBS and centrifuged at 5,000 g for 5 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in ripa buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 10 mM Tris pH8.0, and protease inhibitor cocktail, homogenized and centrifuged at 5,000 g for 5 min at 4°C. Resulting supernatant was spun at 10,000 g for 1 h at 4°C and pellet corresponding to total membrane fraction was collected. The concentration of total membrane protein was measured with Bradford protein assay. Purified Gαq protein (19) was labeled with thiol-reactive Alexa-546 (Invitrogen) and activated using a previously described method (20). Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) measurements between membranes containing GFP-Cav1 membrane and Alexa546-Gαq were measured on ISS spectrofluorometer using a similar procedure as previously described (16). Dilute membrane fractions containing GFP-Cav1 were placed in a 3 mm2 cuvette and Alexa546-Gαq was incrementally added. GFP, the FRET donor, was excited at 488 nm and the emission from the FRET acceptor, Alexa546, was measured from 560 to 660 nm. The degree of FRET was determined from the ratio of Alex546 fluorescence when exciting donor (488 nm) versus its primary absorption at 546 nm. The titration was repeated in the presence of 33 μM Cav3-scaf peptide (Ac-DGIWKASFTTFTVTKYWFYRC).

Immunofluorescence

Cardiac myocytes attached to glass bottom imaging dishes were washed twice with PBS, and fixed with the addition of 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. If required, cells were stimulated with carbachol or isoproterenol before fixation. For pertussis toxin (PTX) pretreatment, the cells were starved and incubated with 100 ng/ml PTX overnight. Fixed cells were washed three times with PBS, and incubated with 0.2% NP40 in PBS for 5min and then blocked in PBS containing 4% goat serum for 1 h. The cells were incubated with primary antibody Gαq, Gβ3, Gαι (Santa Cruz Biochemicals, Santa Cruz, CA) or Cav3 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) at 1:200 dilution with 1% goat serum in PBS for 1 h. Cells were then washed three times for 10 min with 150 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris, pH 7.6, followed by addition of Alexa-Fluor-488-labeled anti-rabbit or Alexa-Fluor-647 anti-mouse secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) diluted to 1:1000 1% goat serum in PBS, and subsequent incubation at 37°C for 1 h and washed three times with TBS. Cells were viewed in TBS buffer on a laser scanning confocal microscope LSM510-Meta (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Confocal imaging and colocalization experiments

Cells were imaged on a laser scanning confocal microscope LSM510 (Carl Zeiss) equipped with multiline laser excitation and a 40×/1.2 NA apochromat water immersion objective. Gβ3, Gα, and Gαq were immunolabeled with Alexa-488. Alexa-488 fluorophore was excited with 488 nm and Argon-ion laser line and images were recorded using BP505-530-nm emission filter. Endogenous Gαq or Cav3 immunolabeled with Alexa-647 were excited with 633-nm line from a He:Ne laser and images were recorded using LP650-nm emission filter. The two fluorophores were excited in a sequential manner using Multi Track acquisition. This procedure minimizes channel cross talk. Colocalization analysis was performed by the overlap method using Zeiss AIM software. Threshold values were determined using the intercellular region of the images.

Fluorescence-correlation-spectroscopy measurements

For a detailed background on fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS), please see the Supporting Material. Measurements were performed on a LSM510–Confocor II apparatus (Carl Zeiss) equipped with a 40×/1.2 NA water immersion objective (Apochromat). eGFP was excited with 488-nm line from the argon ion laser and fluctuations in fluorescence were recorded using LP505-nm filter for 10 s 10 times. Alexa546 was excited with 543-nm He:Ne laser line and fluctuations in fluorescence were recorded using LP560 filter for 10 s 10 times. We calibrated the detection volume by measuring the diffusion of rhodamine (RhG for 488-nm lasers line and RhB for 543-nm laser line) in water. This method of calibration using a standard dye of well-known diffusion coefficient in water, such as rhodamine, is a common procedure (for method and details see (21)). The calibration is an estimation of the 1/e2 beam dimension of the excitation laser. The detection diameter for the 488-nm line was 0.14 ± 0.01 μm and for the 543-nm line was 0.19 ± 0.01 μm. We used the AIM program from Zeiss to fit the autocorrelation curves to the model equation for free Brownian diffusion in two dimensions (22,23) (see the Supporting Material) and calculated the diffusion coefficient, D from the Einstein relation (see the Supporting Material). All measurements were performed at room temperature, 25 ± 1°C, and monitored throughout the experiment using a thermocouple.

FRET studies in FRT cells

Transfection, culture conditions, and FRET imaging of FRTwt and FRTcav+ cells were carried out on a Zeiss Concofor II as previously described (16).

Microinjection experiments

Primary cardiomyocytes were cultured in glass bottom MatTek wells for 24 h. Before microinjections, the media was changed to phenol-free Leibovitz-15 with 14 mM EGTA. The 2 μM Cav3-scaf peptide was injected with trace amounts of DAPI to identify microinjected cells. The control cells were injected with the dye tracer alone. The 2 μM of Gβ3 antibody was immunolabeled with Alexa546 secondary antibody before microinjecting, as the injected sample was fluorescent we did not include tracer dye for these experiments. We used an InjectMan NI2 with a FemtoJet pump from Eppendorf mounted on Axiovert 200 M (Carl Zeiss) equipped with a long working distance 40× phase 2 objective. Using self-pulled needles, we microinjected the sample into the cytoplasm. We typically set the injection pressure Pi = 90 hPa, and kept the compensation pressure Pc = 45 hPa. The injection time was t = 0.7 s. Typically, we injected ∼10–25 cells within a 10- to 20-min period. We examined the microinjected cells under the phase microscope to select viable cells.

Confocal imaging and Calcium sparks measurements

Ventricular cardiomyocytes were incubated with calcium green AM (5 μM; Molecular Probes) for 30 min at room temperature and in the dark, washed two times with Leibovitz15 medium with 14 mM EGTA, and incubated for another 30 min in Leibovitz15 medium containing14 mM EGTA with or without 10 μM U73122 PLC inhibitor. Cells loaded with calcium green were microinjected with peptide and calcium response was measured after stimulation with 5 μM carbachol or 1 μM isoproterenol. Cells were treated with 10 mM xestospongin C or ryanodine as described (24,25).

Confocal fluorescence imaging was performed with a confocal scanning laser microscope system (Fluoview, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) coupled to an inverted microscope (IX70, Olympus) with a 40× objective (UPlanApo, Olympus, numerical aperture 1.3). Calcium green was excited with 488-nm laser line and images were collected using an LP515 emission filter. We collected frames at 500-ms intervals. Intensity values for each pixel were extracted using Olympus software and ImageJ. The line scan mode was used for quantitative analysis of faster Ca2+ transients and Ca2+ sparks. The pixel size used in this study was 0.1–0.3 μm. Line-scan rate was 1.76 ms per 256-pixel line or 1.3 ms per 512-pixel line.

Results

Colocalization between Cav3 and Gβγ decreases with stimulation

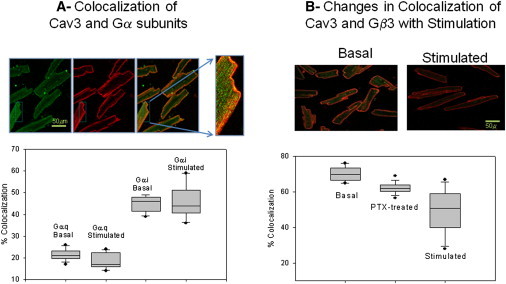

We began this study by testing the idea that caveolae may directly affect intracellular Ca2+ activity by sequestering Gαq subunits, thereby affecting PLCβ activity. For these studies, we used a primary cell line, left ventricular adult canine cardiac myocytes, in which Cav3 is the main structural component of caveolae (26). We first determined the cellular localization and distribution of Cav3 and Gαq by immunofluorescence. For comparison, we also studied Gαi and Gβ3, which do not bind specifically to Cav1 (17), and noted that Gβ3 is the predominant Gβ isoform in adult cardiomyocytes (27). We found that Cav3 is distributed along the sarcomers and Z-lines and very little is seen in internal sites (Fig. 1). In contrast, Gαq, Gα, and Gβ are all seen in internal sites and on the plasma membrane (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

(A) Coimmunofluorescence studies showing the colocalization between Cav3 and Gαq and Cav3 and Gαi in the basal and stimulated states (i.e., after addition of 5 μM carbachol for Gαq and 1 μM isoproterenol for Gαi). (Upper) Example of cells stained for Gαq (green) and Cav3 (red) showing normal and expanded overlay images. (Lower) Compilation of colocalization data from 3 separate experiments where n = 11–18. (B) Similar results of coimmunofluorescence showing the colocalization of Cav3 and Gβ3 in the basal state and stimulated with 5 μM carbachol where p = < 0.001 (ANOVA) for the basal and stimulated groups. The PTX-treated group was stimulated with 5 μM isoproterenol and did not differ significantly from the basal group.

We then measured the amount of colocalization between Cav3 and the G-protein subunits. It is important to note that colocalization is essentially determined by the pixel overlap between one or more fluorescence channels. This measurement will only suggest that the proteins are/are not localized in the same spatial region of the cell, whose resolution is governed by the optical and detection system of the microscope. Therefore, in the studies described below, we base our results on the changes in colocalization of the antibody-tagged proteins under the same cellular conditions, and corroborate colocalization studies with fluorescence fluctuation methods (described below) that are not reliant on spatial restrains. A review of the colocalization and its limitations has been published (28).

We found that Cav3 and G-protein subunits all showed significant colocalization and actual values varied somewhat between the particular subunits (Fig. 1), most likely due to differences between the accessibility of the antibodies to the different epitopdes, the fluorescence properties of the secondary antibodies, and the strength and specificity of the antibody used. We also measured changes in colocalization of the proteins after stimulation with 5 μM carbachol and found that stimulation does not significantly affect the degree of colocalization between Cav3 and Gαq. Similarly, we found that stimulation with 5 μM isoproterenol does not affect the degree of colocalization between Cav3/Gαi (Fig. 1 A). However, carbachol causes a significant overall drop in the mean value of the colocalization between Cav3/Gβ3 (Fig. 1 B). This decrease is diminished when the cells are pretreated with PTX and stimulated with isoproterenol, which will prevent activation of Gαi and Gαo. This result suggests that Gβγ subunits released from activated Gαq and other Gα isotypes can dissociate from caveolae domains.

Stimulation of cardiomyocytes with carbachol increases mobility of Gβγ subunits

The colocalization studies suggest that Gβγ can dissociate from caveolae with carbachol stimulation. We expect that stimulation should increase the mobility of Gβγ as it becomes released from caveolae. To test this idea, we measured the change in the diffusion coefficient of Gβγ in live cardiomyocytes in the basal state and 1–15 min after stimulation. Initially, we carried out these studies by transfecting the cardiomyocytes with eGFP-Gβ1γ7 and monitoring diffusion by FCS (see (29)). Due to the very low transfection efficiency, we were able to collect reliable data for only a few cells (n = 7). We found that the diffusion coefficients of eGFP-Gβ1 in these cells are too slow to be measured. This limited mobility is expected if Gβ1 is localized in large protein domains, such as caveolae. However, the addition of carbachol resulted in an increase in the diffusion constant in all but two of the cells to a value of D = 0.6 ± 0.1 μm2/s, n = 5. The value of this diffusion constant corresponds to a monomeric or a small oligomeric membrane associated protein (i.e., http://www.sbcny.org/membrane_diffusion_coefficients.htm) and shows that carbachol stimulation increases Gβγ mobility.

To support the studies described above, we measured the diffusion coefficient of purified Gβ1γ2 that was covalently labeled with Alexa546 and microinjected into the cardiomyoctyes. Although the diffusion of the microinjected protein was very rapid in some cells suggesting an inappropriate localization, in other cells the microinjected protein had a very limited mobility similar to the transfected protein, suggesting localization in large protein domains. Stimulation of the latter cells with carbachol resulted in increased mobility of Alexa546-Gβ1γ2 to a value comparable to eGFP-Gβ1γ2 transfected under stimulated conditions (D = 0.6 ± 0.1 μm2/s, n = 6). Taken together, the very limited mobility of Gβγ in the basal state, followed by a more rapid diffusion after treatment with carbachol, is consistent with release of a population of Gβγ from caveolae domains with Gαq activation.

Gαq interacts with Cav3 through the scaffold domain

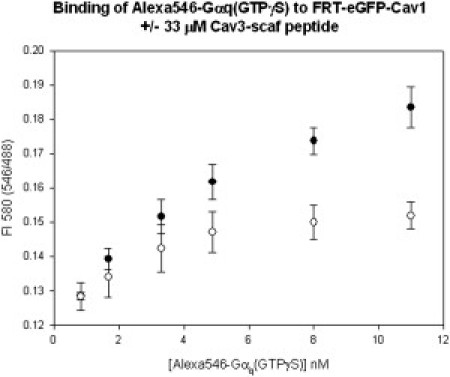

Stabilization of the activated state of Gαq by caveolae, coupled with the release of Gβγ subunits from caveolae domains upon stimulation, would prolong the activation of PLCβ enzymes and increase the duration of Ca2+ events. We tested the idea that Cav3 is playing an active role in Ca2+ signaling by determining the changes in Ca2+ activity when interactions between Cav3 and Gαq are disrupted. For these studies, we first developed a reagent that would interfere with the binding of Cav3 and Gαq. Activated Gαq has been suggested to bind to the scaffold region of Cav1 (30), which has high homology to the scaffold domain of Cav3. We synthesized a peptide corresponding to this sequence (Cav3-scaf). We first tested the ability of Cav3-scaf to interfere with the association between activated Gαq and caveolae. For these studies, we prepared membrane fractions from FRT cells transfected with GFP-Cav1 (these cells do not endogenously express caveolae, but will express and localize GFP-Cav1 appropriately and have been used as models for caveolae studies, see (16,30)).

We measured the association of Alexa546-Gαq to GFP-Cav1 by FRET. FRET will occur when excited energy from a donor molecule (i.e., GFP) is transferred to an acceptor (i.e., Alexa546) when the probes are within ∼50 Å (see (31)). This method allows one to view associations between two soluble or membrane-associated proteins in real time (see (32,33)). The association between the Alexa546-Gαq and GFP-Cav1 is observed by the increase in Alexa546 emission when exciting GFP due to transfer from this donor as compared to its intensity when only Alexa546 is excited.

We tested the ability of the Cav3-scaf peptide to disrupt the association of Gαq to Cav1. We found that Cav3-scaf significantly lowers their association (Fig. 2) due to competition of Cav1 for Gαq. Because the scaffold regions of Cav1 and Cav3 are very homologous but not identical, we expect Cav3-scaf to be a slightly more effective competitor for Gαq–Cav3 association. We then determined whether Cav3-scaf could disrupt the association between Gαq and Cav3 in cardiomyoctyes by microinjecting the peptide into cells and measured its effect on Cav3/Gαq colocalization. We tracked cells that were microinjected by including trace amounts of DAPI in the microinjection solution, which stains the nucleus. We found that the Cav3-scaf peptide significantly reduces the colocalization between Cav3 and Gαq (Fig. 3). Control studies show that Cav3-scaf does not disrupt the association between Gαq and Gβγ subunits.

Figure 2.

Decrease in the association of Alexa546-Gαq(GTPγS) and GFP-Cav1 dispersed in FRT membranes in the absence (●) and presence (○) of Cav3-scaf peptide. In this study, binding was monitored by the increase in FRET, as determined by comparing the fluorescence emission intensity (F.I.) at 580 nm of Alexa546 acceptors exciting only at 546 nm, to the increase in Alexa546 fluorescence emission intensity at 580 nm when exciting GFP donors at 488 nm. The increase in F.I. at λ(em) = 580 nm is due to FRET from the GFP donors (at λ(ex) = 488 nm) to Alexa546 (at λ(ex) = 546).

Figure 3.

Decrease in the colocalization between Gαq and Cav3 in the presence of Cav3-scaf peptide. Here, colocalization was determined by selecting the plasma membrane region rather than the whole cell to yield higher initial values. An identical study showing the lack of change between Gβγ and Cav3 is shown for comparison.

Evidence that caveolin stabilizes the activated state of Gαq

The above studies, along with previous work (16,17) imply that Cav3 stabilizes the activated state of Gαq through specific binding interactions. To support this idea, we carried out a series of studies using the C2 domain of PLCβ1 as a tool to monitor activated Gαq. It has been shown that C2 domain of PLCβ1 binds strongly and specifically to activated Gαq (34). Because this C2 domain does not bind to membranes (34), activation of Gαq should then promote its movement from the cytosol to the plasma membrane.

We expressed PLCβ1-C2 in bacteria, labeled the purified protein with Alexa546, and microinjected the solution into cardiomyocytes. We expected the probe to be primarily cytosolic, but we found that it forms small aggregates throughout cardiomyocytes making changes in localization difficult to assess by fluorescence imaging. Thus, we carried out our studies using FRT cells because we found that in these cells microinjected Alexa546-C2 is freely diffusing and primarily localized in the cytosol, although small amounts are found on the plasma membrane.

We then compared the behavior of Alexa546-C2 microinjected into FRT cells (FRTwt), which do not contain caveolae, to its behavior in a stable Cav1 transfected line that displays caveolae domains (FRTcav+) (see (30)). Additionally, both cell types were transfected with eGFP-Gαq. FRET was then used to determine changes in the association between Alexa546-C2 and eGFP-Gαq. Measurements were taken within 3 min after stimulation where sustained Ca2+ levels in FRTcav+ but not FRTwt cells are observed (16). In the basal state, we found that the amount of FRET is higher in FRTwt versus FRTcav+ cells (5.3 ± 1.0%, n = 13 versus 2.4 ± 0.9%, n = 8 where the values were obtained by comparing the background-corrected FRET to a positive control, eGFP-PHPLCδ1-Alexa546 and a negative control, free eGFP and free Alexa546, see (35)) suggesting that in the absence of caveolae, more Gαq is available for C2 binding. Both cell types show a similar increase in FRET (11.0 ± 2.5%) with stimulation. Three minutes after stimulation, only 16% of the FRTcav+ cells returned to basal level FRET values, whereas 50% of the FRTwt cells returned to basal levels suggesting that the presence of caveolae helps sustain the activated state of Gαq.

To support the FRET studies, we determined the change in the diffusion of Alexa546-C2 microinjected into FRTwt and FRTcav+ cells using FCS. In both FRTwt and FRTcav+ cells, we observed a fast diffusion component that can be correlated with the cytosolic population, and a slower moving population that we interpret to represent the fraction of C2 that is prebound to the plasma membrane. In FRTwt cells, this prebound fraction is significantly higher than in FRTcav+ cells (0.16 ± 0.03, n = 5, versus 0.10 ± 0.01, n = 14) even though the values of their mobility were the same within error (D = 2.5 ± 0.1 μm2/s and D = 2.4 ± 0.2 μm2/s, respectively). The higher amount of prebound material in the caveolae-free cells agrees with the basal state FRET values measured in these cells.

Stimulation of the cells results in distinct effects on the mobility of Alexa546-C2. The fraction of the slow moving population in FRTwt cells significantly decreased from 0.16 ± 0.03 to 0.11 ± 0.02 (p < 0.03) and the corresponding change in mobility was modest (after stimulation, D = 1.8 ± 0.2 μm2/s). In FRTcav+ cells, we observed a small but not significant increase in the fraction of slow population (from 0.10 ± 0.01 to 0.13 ± 0.02) and a small but not significant decrease in mobility from D = 2.4 ± 0.2 μm2/s to 2.0 ± 0.2 μm2/s (n = 13). We interpret the FCS results shown in Fig. 4 as follows: the decrease in the fraction of slow moving population in the caveolae-free cells, with a concomitant increase in association as seen by FRET, is interpreted as detachment of Gαq from the receptor molecules as they cluster and internalize into endosomes. Alternately, in caveolae-containing cells, our data show that an increased amount of Alexa546-C2 bound to a slower moving population of activated Gαq. Coupled with the colocalization studies, these results suggest that caveolae stabilizes the activated form of Gαq.

Figure 4.

Gαq activation, as reported by the mobility of Alexa546-C2 domain, depends on the presence of caveolae. (A) Treatment with 5 μM carbachol significantly decreases the fraction of slowly diffusing particles in FRTwt (hatched), p < 0.03, and does not produce significant changes in FRTcav (solid) cells. (B) The diffusion coefficient of Alexa546-C2 in both cell types is not significantly affected by the carbachol treatment.

To strengthen the argument that caveolae stabilize Gαq, we microinjected Cav3-scaf and Alexa546-C2 into FRTcav+ cells and repeated the FRET and FCS studies. We found that the value of FRET from eGFP-Gαq to Alexa546-C2 returns to basal levels 3 min after stimulation (5.3 ± 1.0%, n = 13 (basal), 5.1 ± 0.8%, n = 5 (3′ after stimulation) suggesting that sustained Gαq activation does not occur in the presence of peptide. Additionally, change in the slow moving fraction in the stimulated state followed the change observed for FRTwt cells (from 0.16 ± 0.02 before stimulation to 13 ± 0.02 after stimulation; n = 6). These results are consistent with the ability of the peptide to compete for Gαq-caveolae interactions, and support the idea that activated Gαq localizes in caveolae domains where its activated state can be prolonged.

Caveolae impacts Ca2+ activity in cardiomyocytes

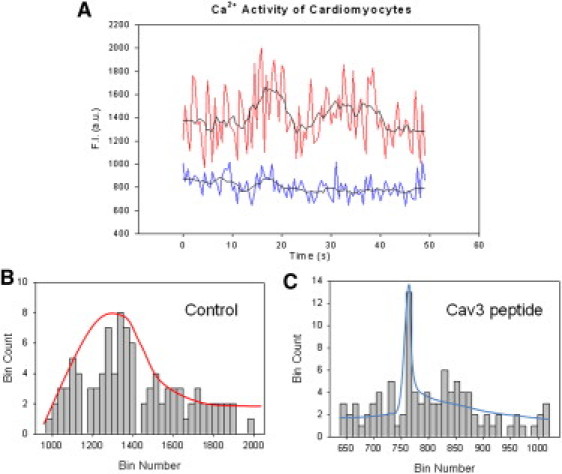

We determined whether the interaction between Gαq and caveolae affects Ca2+ signals in live cardiomyocytes. To isolate Ca2+ release from internal stores through the Gαq-PLCβ mediated pathway, as opposed to extracellular Ca2+ entry, we carried out these studies in Ca2+-free medium. Intracellular Ca2+ levels were monitored using a fluorescent Ca2+ indicator (Ca2+green). We carried out our studies in adult canine ventricular cardiac myocytes that were cultured for 2 days, which allowed firm adhesion of the cells on the substrate as required for microinjection studies (see below). We note that similar behavior was observed using freshly isolated atrial myocytes and no significant differences in the Ca2+ activity between the fresh and cultured ventricular cardiomyocytes were observed.

In the absence of extracellular Ca2+, we observed waves with peak widths of ∼20 s after the addition of 5 μM carbachol (Fig. 5 A, upper trace). These same traces were seen when identical frames were rescanned over 20–100 times at 500-ms intervals. Embedded in these waves were at least two sets or more of many narrow waves having widths in the second and microsecond range. Due to the lack of extracellular Ca2+, these shorter Ca2+ spikes somewhat mask the longer waves caused by release of Ca2+ from internal stores (i.e., puffs). Control studies that measured free dye and electronic noise showed that the very fast events occurring in the millisecond time scale were intensity fluctuations caused by free dye molecules diffusing through the field of view, whereas the slower oscillating was due to intracellular Ca2+ fluctuations.

Figure 5.

(A, Upper trace) Ca2+ activity, as measured by Ca2+ Green intensity, in adult canine ventricular myocytes as a function of time in seconds after the addition of 5 μM carbachol. Raw data is seen as the noisier trace and an average of three traces is the smooth overlaid curve. (Lower trace) Decrease in the Ca2+ activity in canine ventricular myocytes that were microinjected with Cav3-scaff as a function of time in seconds after the addition of 5 μM carbachol. Raw data is seen as the noisier trace and an average of three traces is shown is the smooth overlaid curve (B) Corresponding histogram analysis of the control cells and Cav3-scaf microinjected cells (C) set binned at 35.

We analyzed our data using intensity binning. In this method, the intensity values of a certain magnitude are placed in a particular bin depending on its value. By keeping the time scale of the experiment constant, we can determine the relative number of intensities of a particular value. Thus, narrow or short duration time events would give many similar intensity values and the resulting histograms would be very narrow, but longer waves that give intensities over a longer time period will give a much broader histogram. Binning allows us to group over 500 traces of scans of different cells and regions, along with rescans of the same image, and visualize the compiled results spatially and temporally on a single plot. Thus, the slow Ca2+ waves that may be difficult to discern when the scans are overlaid due to different peak placement and noise can be readily seen in the binned histograms. Binning the data in Fig. 5 B results in a broad skewed Gaussian histogram corresponding to intensities that are spread over a large time range. We note that the shape on this plot will not depend on the number of bins but will depend on the time scale of the scans.

We then compared the Ca2+ behavior of cells that were microinjected with the Cav3-scaf peptide. Injection of this peptide should disrupt Cav3-Gαq association and we found that the Cav3-scaf peptide drastically reduced the magnitude of the slow waves (Fig. 5 A, lower trace) causing the shape of the histogram graph to become very narrow as compared to the control (Fig. 5 C).

To better compare these experiments, we averaged 20–25 sets of experimental data and generated histograms by binning into nine segments (all of the above data were arbitrarily but consistently binned at 35). This smaller bin count allowed all the short spikes to be grouped into the first few bins. In Fig. 6 (upper panels) we show the population of species in each bin. As can be seen, cells that were microinjected with the Cav3-scaf peptide had a considerably higher population of intensities in the shortest time bracket reflecting the elimination of slow waves.

Figure 6.

(Upper panels) Compilation of 25 sets of histograms that were binned into nine sets for control cells (right) and Cav3-scaff microinjected cells (left) showing the differences in bin population and distribution. (Lower) Summary of bin analysis of the Ca2+ activity in canine adult ventricular cardiomyocytes data (see text). Note that myocytes microinjected with Cav3-scaf peptide (●) or treated with the PLC inhibitor U73132 (Δ) had the largest population of intensities in the shorter time bins reflecting the elimination of the Ca2+ slow waves (i.e., Ca2+ puffs). In contrast, untreated cells (▾), cells microinjected with control peptide (■) or cells treated with ryanodine (○) showed bin populations at a longer time reflecting the presence of slow waves.

We carried out several control studies to support the idea that Cav3-Gαq interactions are contributing to Ca2+ activity. We first substituted Cav3-scaf for a control peptide having the same length and charge. Although microinjection of this peptide reduced the magnitude of the Ca2+ signal, it did not affect the properties of the waves (Fig. 6, lower) supporting the idea that the effect of Cav3-scaf on Ca2+ activity is specific. Treatment of the cells with the PLC inhibitor U73132 eliminates the slower Ca2+ waves (Fig. 6, lower) supporting the idea that these waves are generated through the Gαq–PLCβ–IP3 pathway. Treatment of the cells with 1 μM ryanodine, which will completely block RyRs, did not affect the Ca2+ activity as expected because we are carrying out our studies in Ca2+-free media. As a final control, we repeated the studies in fresh, neonatal cardiomyocytes from rat. Rat neonatal cardiomyocytes do not express Cav3 and do not contain caveolae (36). When viewed at short times, we found that only very fast Ca2+ activity is seen and the baseline, which has structure in adult cells due to slow waves, is completely flat showing the absence slow Ca2+ activity (see the Supporting Materials) when Cav3 is not expressed.

Discussion

In this study, we present evidence showing that caveolae regulate slow Ca2+ waves in adult cardiomyocytes through specific interaction with Gαq and linking this pathway to cardiomyopathy in Cav3 null mice (18). Caveloae are perhaps the most well-characterized plasma membrane protein domains and are implicated to play passive roles in many cellular processes (see (10–13)). Interestingly, caveolae are found in many, but not all, mammalian cells implying that they may play a role more in modulating rather than directing cell function. Studies using methods such as cell fractionation and immunofluorescence have suggested that caveolae localizes related proteins into organized domains to allow rapid signaling. In adult cardiomyocytes, many types of G-protein coupled receptors and their corresponding G-proteins have been shown to localize in caveolae domains (38). However, the idea that caveolae can directly affect G-protein signals have only recently been implied from studies using transfected cultured cells (16). In cells that do not contain caveolae, Gαq and Gβγ are complexed in the basal state and remain associated upon stimulation, but in caveolae-containing cells, Gαq separates from Gβγ with carbachol stimulation. This separation appears to result from high affinity interactions between Cav1 and activated Gαq that may prolong the Ca2+ response (16,17).

We carried out the majority of our studies in cardiomyocytes. Adult canine cardiac myocytes contain large and regularly spaced caveolae domains that run along the Z-lines of actin filaments (38). Previous studies found that Cav3 is localized on the plasma membrane which we observe, and also in perinuclear regions (38) which we do not observe. It is possible that these differences may be traced to differences in sample preparation. However, the distributions of G-protein subunits in our study closely match the pattern reported in the study cited above.

In COS and FRT cells, Gαq has been shown to localize in caveolae domains (15,16) and the observed loss in colocalization in cells treated with the Cav3-scaf peptide support a caveolar localization. We also found a high degree of colocalization between Gβγ and Cav3 that decreases with stimulation. Our FCS measurements show that Gβγ subunits are released from large, immobile domains with stimulation. These results suggest that Gαq activation allows movement of Gβγ out of caveolae due to the loss in affinity between the subunits upon activation (19), concomitant with strong binding between activated Gαq and Cav3.

Using the C2 domain of PLCβ1, we obtained evidence that Gαq remains in caveolae domains after activation where it remains activated for a longer period than in the absence of these domains. This behavior can be reversed by the Cav3-scaf peptide that disrupts caveolin-Gαq interactions. The ability of caveolae to stabilize activated Gαq shows that the scaffold domain of Cav3 functions as an inverse GTPase activating protein (i.e., GAP, e.g. (39,40).), and it may be expected to compete for RGS proteins.

Cardiomyocytes have distinct and well-characterized Ca2+ signals that take the form of puffs, sparks, waves, etc., depending on the time of the signal and the extent of localization in the cell (see (1)). The localized Ca2+ signals we observe for adult cardiomyocytes appear as slow oscillating waves. In adult ventricular cardiomyocytes immersed in Ca2+-containing media, localized Ca2+ signals can occur through RyR and Ca2+-induced Ca2+ channels that originate at transverse tubules (i.e., Ca2+ sparks). It is notable that atrial and neonatal cells do not contain transverse tubules and it has been proposed that caveolae help generate Ca2+sparks by coupling RyR in the SR with Ca2+ channels (41). Because our studies were carried out in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, and because the slow Ca2+ waves we observed are independent of RyR, we are not viewing Ca2+ sparks. Rather, our Ca2+ activity falls into the category of puffs, which are signals initiated by IP3 receptors. IP3 is generated by PLC-catalyzed hydrolysis of PIP2, which is stimulated by Gαq activation (see (9)). We find that stimulation of the cells in the absence or presence of extracellular Ca2+ only affects the width of the narrow spikes rather than the slow waves, which is consistent with sparks. In accordance with previous reports, Ca2+ puffs have a pacemaker quality and appear in excitable and nonexcitable cell types (i.e., (41)). Although their amplitude and frequency is cell type-dependent, the basic characteristics of puffs do not differ significantly between cell types consistent with puffs being a basic element of Ca2+ signaling. In HeLa cells, the activity of puff sites will determine whether a global Ca2+ wave or an abortive response is generated (41).

Our localization and diffusion studies show that caveolae influence the time scale of activation and movement of G-proteins with stimulation, whereas our functional studies suggest that the pacemaker-like Ca2+ puffs are under caveolae control. Histogram analysis of Ca2+ activity show that these slower waves are not observed in neonatal cells that do not contain Cav3 (36), when PLC is inhibited or when Gαq-Cav3 association is disrupted by the Cav3-scaf peptide. It is possible that cardiomyocytes have a basal oscillating Gαq signal that is dependent on caveolae through specific binding of Cav3 to Gαq. Release of Gβγ from caveolae domains will remove it from caveolae-localized effectors but promote its association to effectors outside caveolae domains, such as adenylyl cyclase, that may result in sustained signals from Gβγ associated pathways.

Taken together, these studies present strong evidence that caveolae can modulate cell signals. Although other more indirect mechanisms are possible, direct interaction between Cav3 and Gαq, which in turn affect the PLC activity and Ca2+ signals, is the simplest explanation that fits all of our data. Our results offer the possibility that different caveolae domains affect different signaling pathways. Of importance, our studies show that certain cell signals may be manipulated through reagents targeted to caveolin proteins.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ira Cohen (Stony Brook University) and Emila Entcheva for their assistance in providing the cardiomyocytes, to Parijat Sengupta (University of Washington, Pullman) for help in the initial part of this study, and to Eric Sobie (Mt. Sinai School of Medicine) for his helpful suggestions.

This work was supported by National Institiutes of Health grants GM053132 and P50 GM071558.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Cheng H., Lederer W.J. Calcium sparks. Physiol. Rev. 2008;88:1491–1545. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng H., Lederer M.R., Cannell M.B. Calcium sparks and [Ca2+]i waves in cardiac myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;270:C148–C159. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.1.C148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berridge M.J. Inositol trisphosphate and diacylglycerol: two interacting second messengers. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1987;56:159–193. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.001111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berridge M.J. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling. Nature. 1993;361:315–325. doi: 10.1038/361315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fill M., Copello J.A. Ryanodine receptor calcium release channels. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82:893–922. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suh P., Park J., Ryu S. Multiple roles of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C isozymes. BMB Rep. 2008;41:415–434. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2008.41.6.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rebecchi M.J., Pentyala S.N. Structure, function, and control of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Physiol. Rev. 2000;80:1291–1335. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.4.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Exton J.H. Role of G proteins in activation of phosphoinositide phospholipase C. Adv. Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res. 1993;28:65–72. (Review) (21 refs) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Exton J.H. Regulation of phosphoinositide phospholipases by hormones, neurotransmitters, and other agonists linked to G proteins. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1996;36:481–509. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.36.040196.002405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson R.G. The caveolae membrane system. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:199–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ostrom R.S., Insel P.A. The evolving role of lipid rafts and caveolae in G protein-coupled receptor signaling: implications for molecular pharmacology. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2004;143:235–245. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parton R.G., Simons K. The multiple faces of caveolae. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:185–194. doi: 10.1038/nrm2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schlegel A., Volonte D., Lisanti M.P. Crowded little caves: structure and function of caveolae. Cell. Signal. 1998;10:457–463. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(98)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chini B., Parenti M. G-protein coupled receptors in lipid rafts and caveolae: how, when and why do they go there? J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2004;32:325–338. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0320325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oh P., Schnitzer J.E. Segregation of heterotrimeric G proteins in cell surface microdomains. G(q) binds caveolin to concentrate in caveolae, whereas G(i) and G(s) target lipid rafts by default. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:685–698. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.3.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sengupta P., Philip F., Scarlata S. Caveolin-1 alters Ca(2+) signal duration through specific interaction with the G alpha q family of G proteins. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:1363–1372. doi: 10.1242/jcs.020081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murthy K.S., Makhlouf G.M. Heterologous desensitization mediated by G protein-specific binding to caveolin. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:30211–30219. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woodman S.E., Park D.S., Lisanti M.P. Caveolin-3 knock-out mice develop a progressive cardiomyopathy and show hyperactivation of the p42/44 MAPK cascade. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:38988–38997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205511200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Runnels L.W., Scarlata S.F. Determination of the affinities between heterotrimeric G protein subunits and their phospholipase C-β effectors. Biochemistry. 1999;38:1488–1496. doi: 10.1021/bi9821519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chidiac P., Markin V.S., Ross E.M. Kinetic control of guanine nucleotide binding to soluble Galpha(q) Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999;58:39–48. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim S.A., Heinze K.G., Schwille P. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy in living cells. Nat. Methods. 2007;4:963–973. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magde D., Elson E., Webb W.W. Thermodynamic fluctuation in a reaction system - measurement by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1972;29:705–708. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruan Q., Cheng M.A., Mantulin W.W. Spatial-temporal studies of membrane dynamics: scanning fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (SFCS) Biophys. J. 2004;87:1260–1267. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.036483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gafni J., Munsch J.A., Pessah I.N. Xestospongins: potent membrane permeable blockers of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Neuron. 1997;19:723–733. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80384-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oka T., Sato K., Karaki H. Xestospongin C, a novel blocker of IP3 receptor, attenuates the increase in cytosolic calcium level and degranulation that is induced by antigen in RBL-2H3 mast cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;135:1959–1966. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song K.S., Scherer P.E., Lisanti M.P. Expression of caveolin-3 in skeletal, cardiac, and smooth muscle cells. Caveolin-3 is a component of the sarcolemma and co-fractionates with dystrophin and dystrophin-associated glycoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:15160–15165. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.15160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rybin V.O., Steinberg S.F. G protein betagamma dimer expression in cardiomyocytes: developmental acquisition of Gbeta3. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;368:408–413. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.01.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bolte S., Cordelières F.P. A guided tour into subcellular colocalization analysis in light microscopy. J. Microsc. 2006;224:213–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2006.01706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwille P., Haupts U., Webb W.W. Molecular dynamics in living cells observed by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy with one- and two-photon excitation. Biophys. J. 1999;77:2251–2265. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77065-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipardi C., Mora R., Zurzolo C. Caveolin transfection results in caveolae formation but not apical sorting of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins in epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 1998;140:617–626. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.3.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lakowicz J. 2nd ed. Plenum; New York: 1999. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Philip F., Scarlata S. Real-time measurements of protein affinities on membrane surfaces by fluorescence spectroscopy. Sci. STKE. 2006;2006:pl5. doi: 10.1126/stke.3502006pl5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Royer C.A., Scarlata S. Fluorescence approaches to quantifying biomolecular interactions. In: Brand L., Johnson M., editors. Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press; Burlington, MA: 2008. pp. 79–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang T., Pentyala S., Scarlata S. Selective interaction of the C2 domains of phospholipase C-beta1 and -beta2 with activated Galphaq subunits: an alternative function for C2-signaling modules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:7843–7846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo Y., Golebiewska U., Scarlata S. The small G protein Rac1 activates phospholipase Cdelta1 through phospholipase Cbeta2. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:24999–25008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.132654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rybin V.O., Grabham P.W., Steinberg S.F. Caveolae-associated proteins in cardiomyocytes: caveolin-2 expression and interactions with caveolin-3. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2003;285:H325–H332. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00946.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reference deleted in proof.

- 38.Head B.P., Patel H.H., Insel P.A. G-protein-coupled receptor signaling components localize in both sarcolemmal and intracellular caveolin-3-associated microdomains in adult cardiac myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:31036–31044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ross E.M., Wilke T.M. GTPase-activiating proteins for heterotrimeric G proteins: regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) and RGS-like proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000;69:794–827. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iyengar R. There are GAPS and there are GAPS. Science. 1997;275:42–43. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tovey S.C., de Smet P., Bootman M.D. Calcium puffs are generic InsP(3)-activated elementary calcium signals and are downregulated by prolonged hormonal stimulation to inhibit cellular calcium responses. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:3979–3989. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.22.3979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.