Growing evidence supports the notion that proteasome-mediated destruction of transcriptional activators can be intimately coupled to their function1,2. Recently, Nalley et al.,3 challenged this view by reporting that the prototypical yeast activator Gal4 does not dynamically associate with chromatin, but rather ‘locks in’ to stable promoter complexes that are resistant to competition. Here, we present evidence that the assay used to reach this conclusion is flawed, and that promoter-bound, active, Gal4 is indeed susceptible to competition in vivo. Our data challenge the key evidence that Nalley et al., used to reach their conclusion, and suggest that Gal4 functions in vivo within the context of dynamic promoter complexes.

Studies by several groups, including ours1,2,4,5,6, have reported an intimate connection between the activity of transcriptional activators such as Gal4 and Gcn4 and their destruction by ubiquitin–mediated proteolysis. This intimate connection is difficult to reconcile with the conclusion by Nalley et al., that proteolytic turnover of Gal4 is not coupled to its function. This conclusion is based on the result of chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments showing that endogenous, active, Gal4 cannot be competed from the GAL1/10 promoter by induction of a protein with the same DNA binding specificity (‘competitor’). In this case, the competitor contains the hormone-binding domain of the estrogen receptor (ER), which allows its DNA binding activity to be rapidly induced by treatment of yeast with β-estradiol. Yeast cultures expressing both the competitor and endogenous Gal4 are treated with β-estradiol, and ChIP analysis is used to monitor binding of the two proteins to the GAL1/10 promoter.

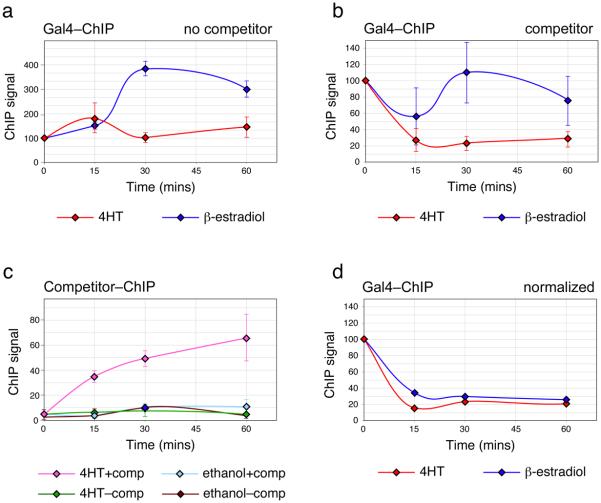

We obtained reagents from the Kodadek laboratory and repeated their experiments. In the course of performing an additional control that was not included in their Nature paper, we observed that—in the absence of any competitor—β-estradiol induced an up to four-fold increase in the levels of Gal4 that associated with the GAL1/10 promoter (a; blue line). The unexpected ability of β-estradiol to induce binding of endogenous Gal4 makes the competition assay difficult to interpret, as the compound is simultaneously inducing both the competitor and the species being competed.

To explore this issue further, we repeated the experiment using a different ER ligand, 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4HT). In the absence of competitor, 4HT had little effect on association of endogenous Gal4 with its cognate promoter (a; red line). Consistent with the different effects of these two ligands on basal association of Gal4 with chromatin, the two compounds gave very different results in the presence of competitor (b). As Nalley et al., published, addition of β-estradiol to yeast expressing the competitor protein resulted in little if any reduction in the levels of endogenous Gal4 at the GAL1/10 promoter, creating the impression that most promoter-bound Gal4 resisted competition (blue line). In the presence of 4HT, however, the opposite result was obtained, and ~75% of endogenous Gal4 was competed from the chromatin within 15 minutes after addition of the ligand (red line). Importantly, the loss of Gal4–chromatin association was accompanied by loading of the competitor onto the GAL1/10 promoter (c), consistent with the notion that the 4HT-activated competitor can displace endogenous Gal4 from the promoter. Although the competitor protein associated with the GAL1/10 promoter with apparently slower kinetics than endogenous Gal4 dissociated (compare red line in (b) with pink line in (c)), it is worth noting that endogenous Gal4 can bind cooperatively to multiple sites in vivo7. There are four Gal4-binding sites in the GAL1/10 promoter. Thus a single competitor bound to one of the sites could have the effect of destabilizing multiple Gal4–promoter complexes, leading to efficient displacement of endogenous Gal4 at substoichiometric levels of competitor.

Based on our observations, we propose that the recalcitrance of Gal4–promoter complexes originally reported by Nalley et al., is an artifact of using β-estradiol to stimulate the competitor. Activating the competitor with 4HT (b), or normalizing the β-estradiol signal to the important ‘no competitor’ control (d), reveals that Gal4 can indeed be rapidly displaced from promoter DNA in vivo. Their conclusion that Gal4–promoter complexes lock in and exhibit long half-lives under activating conditions is thus unsustainable.

Methods

Yeast (BY4741) with or without competitor (Myc-G4-ER-VP16)3 were grown in CSM (2% raffinose) and Gal4 induced by transferring yeast to media containing 2% galactose for one hour. Yeast were then treated with 1 μM 17-β estradiol (Sigma) or 100 μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen (Sigma) for the indicated times. ChIP was preformed5 using either the Gal4-TA C-10 (α-GAL4; Santa Cruz), or AB1 (α-Myc; Calbiochem) antibodies. DNA enrichment was calculated as described8 using ACT1 as the reference locus. Error bars show S.E.M (n=3).

Activation of a Gal4 competitor with β-estradiol versus 4HT.

a, Wild-type yeast were induced with 2% galactose for 60 minutes and β-estradiol or 4HT added. At indicated times, occupancy of endogenous Gal4 on the GAL1/10 promoter was determined by ChIP. ChIP signal is normalized to that at time zero. b, As in (a), except that experiment was performed in yeast expressing the Myc–G4–ER–VP16 competitor (supplied by T. Kodadek3). c, As in the 4HT experiment in (b), except that ChIP was used to monitor association of the Myc–G4–ER–VP16 competitor with the GAL1/10 promoter. The corresponding non-competitor controls are also shown. To calculate the percentage binding in this case, ChIP signals were normalized to those from a Myc–G4–ER–VP16 ChIP (60 minute time point) performed in the absence of endogenous Gal4, which corresponds to the total amount of competitor that can bind in this assay. d, ChIP signals from β-estradiol or 4HT experiments in (b) normalized to the relevant ‘no competitor’ control (a).

References

- 1.Lipford JR, Deshaies RJ. Diverse roles for ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis in transcriptional activation. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:845–850. doi: 10.1038/ncb1003-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muratani M, Tansey WP. How the ubiquitin-proteasome system controls transcription. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:192–201. doi: 10.1038/nrm1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nalley K, Johnston SA, Kodadek T. Proteolytic turnover of the Gal4 transcription factor is not required for function in vivo. Nature. 2006;442:1054–1057. doi: 10.1038/nature05067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipford JR, Smith GT, Chi Y, Deshaies RJA. putative stimulatory role for activator turnover in gene expression. Nature. 2005;438:113–116. doi: 10.1038/nature04098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muratani M, Kung C, Shokat KM, Tansey WP. The F box protein Dsg1/Mdm30 is a transcriptional coactivator that stimulates Gal4 turnover and cotranscriptional mRNA processing. Cell. 2005;120:887–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salghetti SE, Muratani M, Wijnen H, Futcher B, Tansey WP. Functional overlap of sequences that activate transcription and signal ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3118–3123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050007597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giniger E, Ptashne M. Cooperative DNA binding of the yeast transcriptional activator GAL4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:382–386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.2.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ezhkova E, Tansey WP. Chromatin immunoprecipitation to study protein-DNA interactions in budding yeast. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;313:225–244. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-958-3:225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]