Abstract

Alzheimer's disease is the most frequent neurodegenerative disorder and the most common cause of dementia in the elderly. Diverse lines of evidence suggest that amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides have a causal role in its pathogenesis, but the underlying mechanisms remain uncertain. Here we discuss recent evidence that Aβ may be part of a mechanism controlling synaptic activity, acting as a positive regulator presynaptically and a negative regulator postsynaptically. The pathological accumulation of oligomeric Aβ assemblies depresses excitatory transmission at the synaptic level, but also triggers aberrant patterns of neuronal circuit activity and epileptiform discharges at the network level. Aβ-induced dysfunction of inhibitory interneurons likely increases synchrony among excitatory principal cells and contributes to the destabilization of neuronal networks. Strategies that block these Aβ effects may prevent cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease. Potential obstacles and next steps toward this goal are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer's disease is associated with the accumulation of pathogenic amyloid-β (Aβ) assemblies in the brain and results in the progressive dismantling of synapses, neuronal circuits and networks. In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that Aβ oligomers reduce glutamatergic synaptic transmission strength and plasticity1, 2, 3. Subsequent studies provided evidence that neuronal activity regulates Aβ production4, 5 and that elevated Aβ attenuates excitatory synaptic transmission by decreasing the number of surface AMPA receptors (AMPARs) and NMDA receptors (NMDARs), associated with a collapse of glutamatergic dendritic spines4, 6, 7.

More recently, we and others have begun to investigate the effects of Aβ at the level of neuronal circuits and wider networks. These studies have yielded unexpected results. In mice transgenic for human amyloid precursor protein (hAPP), pathologically elevated levels of Aβ promote the formation of pathogenic Aβ oligomers and cause wide fluctuations in the neuronal expression of synaptic activity–regulated genes8, as well as epileptiform activity and nonconvulsive seizures8. It also increases the proportion of abnormally hypoactive or hyperactive neurons in cortical circuits9.

In humans with Alzheimer's disease, increased Aβ is also associated with complex derangements of neuronal activity. For example, hypometabolic regions in the parietal cortex show aberrant increases in neuronal activity during memory encoding10, 11, and individuals from many pedigrees with early-onset autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease have epileptic activity12. Thus, synaptic depression and aberrant patterns of neuronal network activity seem to coexist not only in mouse models, but also in the human condition. This intriguing scenario suggests that Aβ, and possibly other Alzheimer's disease–related factors, have a central role in controlling neuronal activity at specific types of synapses, wider neuronal networks, or both.

Here we discuss recent findings indicating that Aβ is part of an activity-regulated mechanism that controls synaptic excitatory activity, in which Aβ induces presynaptic facilitation at low concentrations and postsynaptic depression at high concentrations. Aβ also causes GABAergic dysfunction, which may contribute to the development of aberrant synchrony in neural networks and disruption of cognitive functions.

Investigating Aβ in Alzheimer's disease

It is likely that diverse factors contribute to the pathogenesis of late-onset Alzheimer's disease13, 14, 15. Among them, Aβ and the genetic risk factor apolipoprotein (apo)-E4 stand out on the basis of overwhelming genetic evidence and strong experimental data16, 17, 18, 19. Mutations in genes encoding hAPP, presenilin 1 (PS1) or presenilin 2 (PS2) that cause early-onset autosomal dominant familial Alzheimer's disease (FAD) increase the production of Aβ ending at amino acid 42 (Aβ42), the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio or Aβ aggregation. Although not identical, early-onset FAD and sporadic late-onset Alzheimer's disease show wide clinical and pathological overlap20 and thus may share common Aβ-dependent mechanisms of cognitive dysfunction.

To study this complex human disease, researchers have used many in vitro and in vivo models. Increased levels of Aβ in these experimental models are commonly achieved by overexpression of FAD-mutant forms of hAPP (with or without overexpression of PS1) in neurons; by exogenous application of synthetic, purified, or naturally secreted Aβ; or by inhibiting Aβ-degrading enzymes. Much of what we know about the effects of Aβ on neural function has been gleaned from the analysis of such models, particularly transgenic mice, acute brain slice preparations and cultures of neural cells or tissues. Human Aβ can exist in diverse assembly states, including monomers, dimers, trimers, tetramers, dodecamers, higher-order oligomers and protofibrils, as well as mature fibrils, which can form microscopically visible amyloid plaques in brain tissues21.

Much evidence suggests that Aβ oligomers are more potent than Aβ fibrils and amyloid deposits in eliciting abnormalities in synaptic functions and neural network activity7, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29. Therefore, many recent studies focusing on functional Aβ effects have used oligomers of human Aβ prepared from synthetic Aβ peptides30, isolated from transfected cell lines24 or purified from brains affected by Alzheimer's disease25. Most of these preparations are devoid of Aβ fibrils and contain Aβ monomers as well as diverse Aβ oligomers that may be in dynamic equilibrium with one another. Different studies have only rarely used strictly comparable Aβ preparations. Nevertheless, the results obtained with different Aβ oligomer preparations have yielded rather consistent results. For example, although synthetic Aβ oligomer preparations are less potent than Aβ oligomers isolated from the supernatant of transfected cell cultures, their effects on acute hippocampal slices are qualitatively similar30, 31. Therefore, we will only comment on the specifics of Aβ preparations when they stand out as unusual or unique. Notwithstanding this approach, we do consider the better standardization of Aβ preparations across studies an important objective.

The diversity of Aβ assemblies in most preparations of human Aβ42 makes it difficult to interpret the precise contribution of molar concentrations of Aβ to the observed physiological alterations. Most studies have used Aβ oligomer preparations whose Aβ content is equivalent to that of a high picomolar, nanomolar or low micromolar concentration of monomeric Aβ. The question then arises of what concentration of Aβ monomers or specific oligomers should be considered normal or physiological and what concentration abnormally low, high or pathological. The answer is unknown and will depend, in part, on whether the Aβ is located within or around the synaptic cleft, near a specific receptor, or within a particular intracellular compartment. Because of these issues, we will simply consider physiological ranges of Aβ to be those found in any given compartment in healthy young adults without cognitive impairments. Any increase in an Aβ species above this level that is associated with functional impairments might be abnormally 'high' or 'elevated'. As illustrated by the marked adverse vascular effects of prolonged subtle elevations in diastolic blood pressure, even small changes in critical variables can have profound biological consequences in the long run.

Modulation of synaptic transmission by Aβ

Synaptic loss is one of the pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease and the best correlate of cognitive decline32, 33, suggesting that it is a critical event in the pathophysiology of the disease. In vivo and in vitro studies have demonstrated that high levels of Aβ reduce glutamatergic synaptic transmission and cause synaptic loss1, 3, 4, 34.

Notably, the production of Aβ and its secretion into the extracellular space are tightly regulated by neuronal activity in vitro4 and in vivo5. Increased neuronal activity enhances Aβ production, and blocking neuronal activity has the opposite effect4. This synaptic regulation of Aβ production is mediated, at least in part, by clathrin-dependent endocytosis of surface APP at presynaptic terminals, endosomal proteolytic cleavage of APP, and Aβ release at synaptic terminals5. In addition, pathogenic Aβ species can also be released from dendrites35. This tight neuronal activity–dependent regulation of Aβ secretion has been observed during pathological events, such as epileptiform activity induced by electrical stimulation5, as well as during normal physiological processes, such as the sleep–wake cycle36. It is also supported by the earlier development of amyloid plaques in patients with epilepsy37. These findings support the notion that APP and Aβ are part of a feedback loop that controls neuronal excitability4. In this model (Fig. 1), Aβ production is enhanced by action potential–dependent synaptic activity, leading to increased Aβ at synapses and reduction of excitatory transmission postsynaptically. Pathological elevation of Aβ would be expected to put this negative feedback regulator into overdrive, suppressing excitatory synaptic activity at the postsynaptic level.

Figure 1. Presynaptic and postsynaptic regulation of synaptic transmission by Aβ.

(a) Hypothetical relationship between Aβ level and synaptic activity. Intermediate levels of Aβ enhance synaptic activity presynaptically, whereas abnormally high or low levels of Aβ impair synaptic activity by inducing postsynaptic depression or reducing presynaptic efficacy, respectively. (b) Within a physiological range, small increases in Aβ primarily facilitate presynaptic functions, resulting in synaptic potentiation38,39. (c) At abnormally high levels, Aβ enhances LTD-related mechanisms, resulting in postsynaptic depression and loss of dendritic spines4,7,31,46.

However, a recent study suggests that Aβ also acts as a positive regulator at the presynaptic level (Fig. 1a,b). In this study, relatively small increases in endogenous Aβ abundance (~1.5-fold), induced by inhibition of extracellular Aβ degradation in otherwise unmanipulated wild-type neurons, enhanced the release probability of synaptic vesicles and increased neuronal activity in neuronal culture38. Enhanced extracellular Aβ increased spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents without significantly altering inhibitory currents. All these effects were exclusively presynaptic and dependent on firing rates, with less facilitation seen in neurons with higher firing rates. Thus, small increases of Aβ may facilitate presynaptic glutamatergic release in neurons with low activity but not in neurons with high activity.

Consistent with this finding, application of low (picomolar range) concentrations of Aβ markedly potentiates synaptic transmission, whereas higher concentrations (low nanomolar range) of Aβ cause the expected synaptic depression39. The potentiating effect of Aβ does not affect postsynaptic NMDAR and AMPAR currents but is dependent on α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) activation, suggesting a presynaptic mechanism mediated by build-up of Ca2+ in presynaptic terminals (Fig. 1b). Thus, Aβ may directly act on presynaptic α7-nAChR40 and be part of a positive feedback loop that increases presynaptic Ca2+ and Aβ secretion. Indeed, blocking nAChRs or removing α7-nAChRs decreases Aβ secretion and blocks Aβ-induced facilitation35. Of particular importance, Aβ-induced presynaptic facilitation depends on an optimal Aβ concentration, with higher or lower concentrations impairing synaptic transmission38. A positive modulatory effect of Aβ on synaptic transmission is further supported indirectly by the finding that an abnormally low Aβ level in mice deficient in APP (ref. 41), PS1 (ref. 42) or BACE1 (ref. 43) is associated with synaptic transmission deficits.

Overall, the above data suggest a bell-shaped relationship between extracellular Aβ and synaptic transmission in which intermediate levels of Aβ potentiate presynaptic terminals, low levels reduce presynaptic efficacy and high levels depress postsynaptic transmission (Fig. 1a).

Elevated Aβ impairs synaptic transmission

Excitatory synaptic transmission is tightly regulated by the number of active NMDARs and AMPARs at the synapse. NMDAR activation has a central role, as it can induce either long-term potentiation (LTP) or long-term depression (LTD), depending on the extent of the resultant intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) rise in the dendritic spines and the downstream activation of specific intracellular cascades44. Activation of synaptic NMDARs and large increases in [Ca2+]i are required for LTP, whereas internalization of synaptic NMDARs, activation of perisynaptic NMDARs and lower increases in [Ca2+]i are necessary for LTD. LTP induction promotes recruitment of AMPARs and growth of dendritic spines, whereas LTD induces spine shrinkage and synaptic loss44.

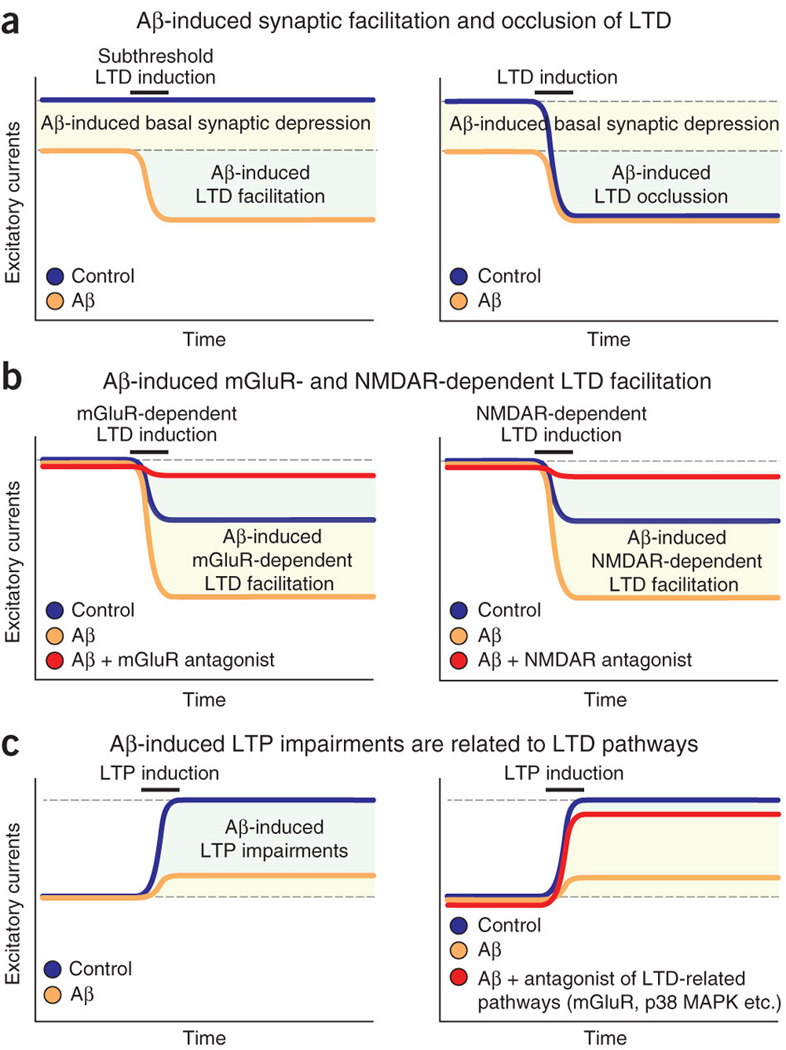

Pathologically elevated Aβ may indirectly cause a partial block of NMDARs and shift the activation of NMDAR-dependent signaling cascades toward pathways involved in the induction of LTD and synaptic loss4, 6, 7. This model is consistent with the fact that Aβ impairs LTP3, 29 and enhances LTD6, 31, 45 (Fig. 2). Although the mechanisms underlying Aβ-induced LTD have not yet been fully elucidated, they may involve receptor internalization6, 46 or desensitization47 and subsequent collapse of dendritic spines6, 46. Aβ-dependent effects on synaptic function may be mediated by activation of α7-nAChR46, perisynaptic activation of NMDARs7, 31 and downstream effects on calcineurin–STEP–cofilin, p38 MAPK and GSK-3β signaling pathways7, 30, 31, 48.

Figure 2. Depression of excitatory synapses by high Aβ levels requires activation of mGluR- and NMDAR-dependent LTD pathways.

Panels depict summary diagrams; for details and actual data, see the papers cited below. (a) Aβ suppresses basal excitatory synaptic transmission (left and right), facilitates LTD after subthreshold LTD inductions (left)31 and occludes LTD (right)6, suggesting that Aβ-induced synaptic depression recruits LTD-like mechanisms. (b) Aβ facilitates LTD by inducing activation of mGluRs (left) and NMDARs (right). Aβ-induced facilitation of mGluR-dependent LTD is suppressed by mGluR antagonists (left, red), and Aβ-induced facilitation of NMDAR-dependent LTD is suppressed by NMDAR antagonists (right, red)31. (c) Aβ-induced LTP deficits depend on activation of LTD pathways. Aβ potently inhibits LTP (left). Blocking LTD-related signaling cascades with mGluR5 antagonists or an inhibitor of p38 MAPK (right, red) prevents Aβ-induced LTP impairments30.

Recent findings suggest that pathologically elevated Aβ blocks neuronal glutamate uptake at synapses, leading to increased glutamate at the synaptic cleft31. A rise in glutamate would initially activate synaptic NMDARs, which might be followed by desensitization of the receptors and, ultimately, synaptic depression. A second effect of increased glutamate would be a spillover and activation of extra- or perisynaptic NR2B-enriched NMDARs, which have a key role in LTD induction47. The activation of perisynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) may also be involved in the facilitation of LTD by Aβ6, 31 (Fig. 2a,b). Thus, Aβ-induced synaptic depression may result from an initial increase in synaptic activation of NMDARs by glutamate, followed by synaptic NMDAR desensitization, NMDAR and AMPAR internalization, and activation of perisynaptic NMDARs and mGluRs. Aβ-induced LTD-like processes may underlie Aβ-induced LTP deficits, as blocking LTD-related signaling cascades, such as those mediated by mGluR or p38 MAPK, prevents Aβ-dependent inhibition of LTP30 (Fig. 2c).

Elevated Aβ destabilizes neural network activity

Physiological levels of Aβ may facilitate neuronal activity by presynaptic potentiation. This positive feedback loop is unlikely to escalate into aberrant network activity under normal circumstances, as increased neuronal activity would further enhance Aβ production, triggering negative postsynaptic regulation of excitatory synaptic transmission (Fig. 1). Dysregulation of Aβ in Alzheimer's disease could override these activity-dependent synaptic mechanisms, leading to synaptic failure and cognitive decline. Indeed, even small chronic increases in Aβ ultimately lead to synaptic depression38. Pathologically elevated Aβ may also affect cognitive performance by inducing abnormal patterns of neuronal activity and compensatory responses at the level of neuronal circuits and networks49. For the purposes of this discussion, we define neuronal circuits as smaller assemblies of interconnected neurons within a specific brain region and neuronal networks as larger assemblies of interconnected circuits involving different brain regions.

Our working model of Aβ-induced cognitive dysfunction proposes that high Aβ leads to aberrant excitatory network activity and compensatory inhibitory responses involving learning and memory circuits, and that both alterations contribute to cognitive decline8, 50. Hippocampal compensatory responses may include calbindin depletion, GABAergic sprouting and ectopic expression of inhibitory neuropeptides8, 51, 52.

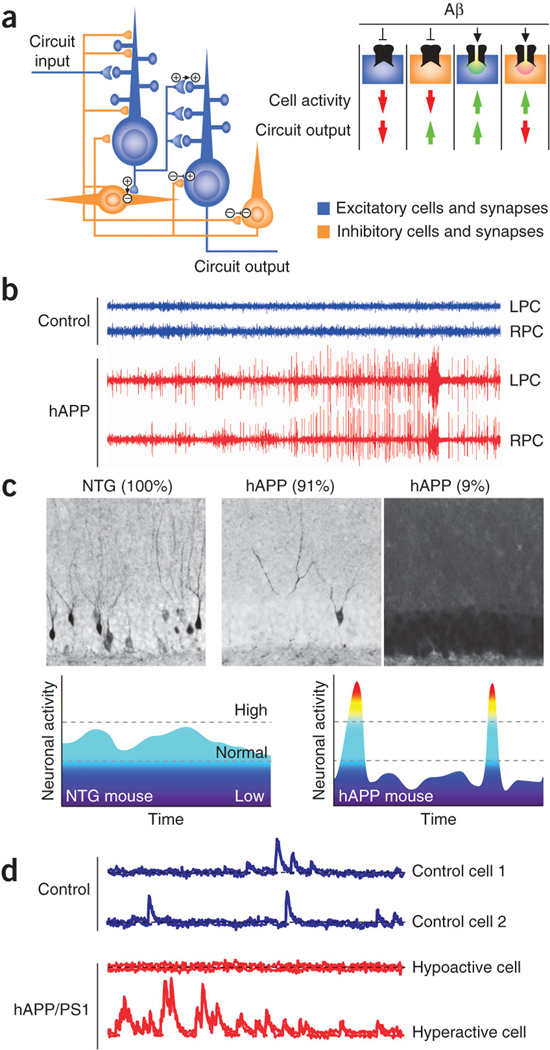

Although the effects of Aβ on specific hippocampal glutamatergic synapses have been studied extensively, fewer investigations have focused on the effects of Aβ on neuronal circuits and more complex neuronal networks. Neuronal circuits are assembled through very large numbers of synaptic interactions between excitatory, inhibitory and neuromodulatory cells (Fig. 3a). The overall effect of Aβ probably depends critically on the abundance of Aβ at each synapse, the intrinsic vulnerability of each synaptic type, the circuit architecture and the engagement of 'nonphysiological' targets by high levels of pathogenic Aβ assemblies. It is possible that Aβ affects excitatory and inhibitory synapses differentially, which could produce complex imbalances in circuit and network activity.

Figure 3. Pathologically elevated Aβ elicits abnormal patterns of neuronal activity in circuits and in wider networks in Alzheimer’s disease–related mouse models.

(a) Neuronal circuits are formed by synaptic interactions between excitatory and inhibitory cells. Aβ might differentially affect excitatory (+) and inhibitory (−) synapses and cells, producing complex imbalances in circuit and network activity. (b) At the network level, high levels of Aβ increase network synchrony and elicit epileptiform activity, as illustrated here in EEG recordings from the left and right parietal cortex (LPC and RPC, respectively) of nontransgenic (NTG) controls (blue) and hAPP transgenic mice from line J20 (red)8. (c) hAPP mice show fluctuations in the neuronal expression of synaptic activity–dependent genes, suggesting network instability. Top: compared with NTG controls (left), hAPP-J20 mice show abnormally low (middle) or high (right) Arc expression in granule cells of the dentate gyrus. (Adapted with permission from refs. 8, 76). Percentages indicate the proportion of mice showing the different patterns of Arc expression. Such marked increases in Arc expression are typically caused by seizure activity. Bottom: interpretive diagram. Marked fluctuations in neuronal activity may directly impair cognition by reducing the time the network spends in activity patterns that promote normal cognitive functions. (d) In cortical circuits of mice monitored in vivo by calcium imaging, most neurons in NTG controls (blue traces) have an intermediate level of activity, whereas many neurons in hAPP/PS1 transgenic mice with high Aβ levels (red traces) are either hypoactive (top) or hyperactive (bottom). (Adapted with permission from ref. 9).

Several recent reports in Alzheimer's disease–related mouse models suggest that pathologically elevated Aβ destabilizes neuronal activity at the circuit and network levels. We demonstrated by electroencephalogram (EEG) recording from cortical and hippocampal networks in hAPP transgenic mice that elevation of Aβ elicits epileptiform activity, including spikes and sharp waves8 (Fig. 3b). hAPP mice also have intermittent unprovoked seizures involving diverse regions of the neocortex and hippocampus that are not accompanied by tonic or clonic motor activity. These results demonstrate that chronic exposure to pathologically elevated Aβ is sufficient to elicit epileptic activity in vivo, a conclusion that is also supported by findings obtained in other hAPP lines53, 54, 55.

These aberrant patterns of neuronal activity are associated with wide fluctuations in the neuronal expression of synaptic activity–regulated gene products, such as Arc and Fos, in the dentate gyrus8 (Fig. 3c). Consistent with these findings, in vivo calcium imaging of cortical circuits shows that hAPP and PS1 doubly transgenic (hAPP/PS1) mice have a greater proportion of hyperactive and hypoactive neurons than nontransgenic controls9 (Fig. 3d). Notably, these Alzheimer's disease–related mouse models have reduced glutamatergic excitatory currents and synaptic loss, suggesting that high Aβ leads to aberrant patterns of neuronal activity by enhancing synchrony among the remaining glutamatergic synapses rather than by increasing excitatory synaptic activity per se.

The processes described above would be expected to diminish the amount of time neural networks spend in activity patterns that promote normal cognitive functions (Fig. 3c). In this context, it is noteworthy that hippocampal alterations in synaptic activity-regulated proteins are tightly associated with learning and memory deficits in independent hAPP transgenic lines26, 51, 56. Moreover, experimental manipulations that prevent seizure activity and compensatory responses in hAPP mice also prevent cognitive deficits in these models57, suggesting that Aβ-induced aberrant network synchronization could contribute to cognitive impairments in Alzheimer's disease.

Although the incidence of seizures in individuals with late-onset Alzheimer's disease is clearly higher than that in age-matched undemented controls12, 58, frank convulsive seizures are rare and only affect 5% to 20% of patients with Alzheimer's disease. In contrast, individuals from many pedigrees with autosomal dominant early-onset Alzheimer's disease show generalized convulsive seizures and myoclonic activity12, 59, 60, 61. Seizures are part of the natural history of Alzheimer's disease associated with any one of over 30 different PS1 mutations59 and have been observed in 31% of FAD patients with PS2 mutations62, 56% of patients with APP duplications61, ~83% of pedigrees with very early-onset Alzheimer's disease (<40 years)60, and 84% of Down syndrome patients who develop Alzheimer's disease63. The incidence of nonconvulsive epileptiform activity in early- or late-onset Alzheimer's disease is unknown.

Radiological studies have also provided evidence for abnormal network activity in Alzheimer's disease. Hypometabolism visualized by positron-emission tomography or single-photon-emission computed tomography and atrophy visualized by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are particularly prominent in posterior components of the 'default network'20, 64 (Fig. 4a). These alterations may reflect overall decreases in neuronal and synaptic activity but could also result from intermittent excesses in excitatory neuronal activity, which are often associated with decreased rather than increased cerebral metabolism65. Consistent with the latter possibility, functional MRI (fMRI) studies have revealed aberrant increases in default network activity during memory encoding in subjects with Alzheimer's disease11 (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4. Radiological evidence for aberrant activity in neuronal networks of humans with Alzheimer’s disease.

(a) The ‘default network’ (left) represents a group of brain regions that are activated at rest and deactivated during memory tasks in healthy controls. It includes the temporoparietal cortex, precuneus and posterior cingulate cortex. Individuals with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) show hypometabolism (middle) and atrophy (right) in these regions, possibly related to abnormal neuronal and synaptic activity. (Adapted with permission from ref. 64). (b) During memory encoding, individuals with Alzheimer’s disease show aberrant increases in default network activity compared with that in undemented controls. (Adapted with permission from ref. 11).

Aberrant network synchronization

Abnormalities in synaptic activity could cause network instability and promote synchrony, which in turn can lead to epileptiform activity. It is also likely that Aβ-induced synaptic depression affects distinct types of synapses, neurons and brain regions differentially, which could further enhance imbalances and instability. Emerging evidence suggests that GABAergic dysfunction may be key in the pathogenesis of network dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Aβ-induced dysfunction of inhibitory interneurons could promote aberrant synchrony in neural networks.

(a) GABAergic interneurons regulate the activity of multiple excitatory principal cells (left). Action potentials (vertical strokes) of GABAergic interneurons and excitatory principal cells generate oscillatory electrical activity that can be detected by EEG recordings (right). Aβ-induced impairments of interneurons could disrupt this regulation and elicit abnormal patterns of network activity. (b) Hypothetical diagram depicting the firing pattern of cortical pyramidal neurons (cells 1–4) in nontransgenic (left) and hAPP transgenic (right) mice. Low excitatory neuronal activity or dysfunction of inhibitory interneurons can shift the activity of excitatory neuronal populations from a normal pattern (left) to a more synchronous pattern (right). Notably, increased synchrony resulting from enhanced GABAergic activity can also lead to epileptic activity77. (c) Actual EEG recordings from nontransgenic (left) and hAPP transgenic (right) mice. There is increased synchrony, reflected by spikes and sharp waves, in the hAPP transgenic mouse.

An important clue came from the finding that hyperactive neurons in cortical circuits of hAPP/PS1 mice are associated with decreased GABAergic inhibition rather than increased glutamatergic transmission, suggesting impairments in GABAergic function9. Mouse models of apoE4, the main genetic risk factor for Alzheimer's disease, show prominent GABAergic dysfunction and impaired GABA release in the hippocampus66. Another interesting report indicates that APP expression regulates GABAergic function by altering L-type calcium channels expressed by GABAergic neurons67. Specifically, APP removal increases L-type calcium channel numbers and calcium currents in GABAergic interneurons in vivo, thereby enhancing GABAergic function and GABAergic plasticity. These effects are reversed by overexpression of APP. Thus, APP or Aβ may regulate ion channels that are critically involved in cellular excitability.

hAPP mice and humans with Alzheimer's disease have high levels of metenkephalin in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, which could block µ-opioid receptors on inhibitory interneurons and thereby disinhibit neuronal networks52. Pharmacological blockade of these receptors improves the memories of hAPP mice in the water maze52.

In addition to acting through neuronal mechanisms, Aβ may alter non-neuronal functions important for network stability. Spontaneous or neuron-induced rises in astroglial [Ca2+]i can release glutamate and activate extrasynaptic NR2B subunit–containing NMDARs on neurons, promoting neuronal excitability and synchronized firing in hippocampal pyramidal neurons68. Glutamate released from astrocytes can also act presynaptically on mGluRs, increasing the probability of transmitter release in glutamatergic terminals69. Of note, astrocytes from hAPP/PS1 mice have synchronous hyperactivity in [Ca2+]i transients across long distances that is uncoupled from neuronal activity70. In addition, activated microglia in Alzheimer's disease generate inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines, that can enhance neuronal excitability71. Thus, diverse mechanisms could contribute to network dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease.

Unresolved issues and next steps

Despite advances in our understanding of Aβ-induced neuronal dysfunction, several issues remain to be addressed more conclusively.

Develop tools to detect and manipulate specific Aβ assemblies in vivo

Although many studies in Alzheimer's disease–related experimental models indicate that Aβ oligomers are a more important cause of synaptic and cognitive dysfunction than plaques, it is still impossible to measure Aβ oligomers in the brains of living people. This issue is a major obstacle in the interpretation of clinical trials aimed at Aβ. If Aβ oligomers are functionally more important than plaques, it would be critical to know whether any given anti-Aβ treatment actually affects their abundance. Otherwise, the clinical trial may fall short of achieving one of its most important proximal end points. Similarly, modulating the abundance of specific Aβ oligomers in brain tissues of rodent models could be highly informative but is difficult, if not impossible, at this time. Determining the state of specific Aβ oligomerization in brain tissues is also subject to certain caveats, as it requires homogenization of the brain, and thus the preparation might not accurately reflect the oligomerization states in the intact brain.

Determine which types of neurons, synapses and molecules are most affected by pathogenic Aβ assemblies

The overall effect of Aβ on the output of neuronal circuits could depend critically on differential vulnerabilities of specific neurons and synapses within these circuits (Fig. 3). However, the pathophysiological effects of Aβ have so far been assessed in very few neural preparations and synaptic connections. Another important unresolved question is whether Aβ oligomers alter synaptic and cognitive functions by interacting with specific neuronal or glial receptors (for example, the α7-nAChR40, RAGE72 and PrPc73) and/or by altering membrane properties through other means (for example, by forming pores74, 75).

Determine the relationship between Aβ-induced alterations at the level of synapses, circuits, networks and cognitive function

Even under physiological conditions, it has been difficult to predict the activity of neural circuits and networks by analyzing individual neurons and synapses. It is therefore not surprising that it has been equally difficult to predict the effects of Aβ at the network level from its effects on specific synapses. EEG recordings in behaving mice8 and calcium imaging to monitor the activity of neuronal populations in live mice9 have begun to unravel the network effects of Aβ, but more research is clearly needed here. A particularly important objective is to determine which aspect of neuronal dysfunction is most directly related to cognitive decline. Better methods are needed to monitor and quantify the activity of synapses and neuronal networks in vivo.

Address the multifactoriality and etiologic heterogeneity of Alzheimer's disease

Although much evidence supports a causal role of Aβ in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease, many other factors—other APP metabolites, tau, apoE4, α-synuclein, vascular alterations, glial responses, inflammation, oxidative stress, epigenetic determinants and environmental factors—may all have important co-pathogenic roles, especially in the most common forms of sporadic Alzheimer's disease. There is an urgent need to elucidate the relative pathogenic impact of these factors and unravel the functional consequences of their interactions. More studies are also needed to determine which mechanisms are most amenable to therapeutic interventions. Addressing these questions should be rewarding from both a therapeutic and a basic neuroscience perspective.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a Stephen D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation Young Investigator Award to J.J.P., and National Institutes of Health Grants AG022074 and NS041787 to L.M. We thank A. Kreitzer for helpful comments on the manuscript; and G. Howard and S. Ordway for editorial review.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hsia AY, et al. Plaque-independent disruption of neural circuits in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:3228–3233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapman PF, et al. Impaired synaptic plasticity and learning in aged amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. Nat. Neurosci. 1999;2:271–276. doi: 10.1038/6374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh DM, et al. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid β protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416:535–539. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamenetz F, et al. APP processing and synaptic function. Neuron. 2003;37:925–937. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cirrito JR, et al. Synaptic activity regulates interstitial fluid amyloid-β levels in vivo. Neuron. 2005;48:913–922. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsieh H, et al. AMPAR removal underlies Aβ-induced synaptic depression and dendritic spine loss. Neuron. 2006;52:831–843. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shankar GM, et al. Natural oligomers of the Alzheimer amyloid-β protein induce reversible synapse loss by modulating an NMDA-type glutamate receptor-dependent signaling pathway. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:2866–2875. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4970-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palop JJ, et al. Aberrant excitatory neuronal activity and compensatory remodeling of inhibitory hippocampal circuits in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2007;55:697–711. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busche MA, et al. Clusters of hyperactive neurons near amyloid plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2008;321:1686–1689. doi: 10.1126/science.1162844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minoshima S, et al. Metabolic reduction in the posterior cingulate cortex in very early Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 1997;42:85–94. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sperling RA, et al. Amyloid deposition is associated with impaired default network function in older persons without dementia. Neuron. 2009;63:178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palop JJ, Mucke L. Epilepsy and cognitive impairments in Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 2009;66:435–440. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blennow K, de Leon MJ, Zetterberg H. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 2006;368:387–403. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mucke L. Neuroscience: Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2009;61:895–897. doi: 10.1038/461895a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bertram L, Tanzi RE. Thirty years of Alzheimer’s disease genetics: the implications of systematic meta-analyses. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008;9:768–778. doi: 10.1038/nrn2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farrer LA, et al. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1997;278:1349–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanzi RE, Bertram L. Twenty years of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid hypothesis: a genetic perspective. Cell. 2005;120:545–555. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahley RW, Weisgraber KH, Huang Y. Apolipoprotein E4: a causative factor and therapeutic target in neuropathology, including Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:5644–5651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600549103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frisoni GB, et al. The topography of grey matter involvement in early and late onset Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2007;130:720–730. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glabe CG. Structural classification of toxic amyloid oligomers. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:29639–29643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800016200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selkoe DJ. Soluble oligomers of the amyloid beta-protein impair synaptic plasticity and behavior. Behav. Brain Res. 2008;192:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klein WL, Krafft GA, Finch CE. Targeting small Aβ oligomers: the solution to an Alzheimer’s disease conundrum. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:219–224. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01749-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh DM, Selkoe DJA. β oligomers – a decade of discovery. J. Neurochem. 2007;101:1172–1184. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shankar GM, et al. Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer’s brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat. Med. 2008;14:837–842. doi: 10.1038/nm1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng IH, et al. Accelerating amyloid-β fibrillization reduces oligomer levels and functional deficits in Alzheimer disease mouse models. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:23818–23828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701078200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomiyama T, et al. A mouse model of amyloid β oligomers: their contribution to synaptic alteration, abnormal tau phosphorylation, glial activation, and neuronal loss in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:4845–4856. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5825-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LesnÈ S, et al. A specific amyloid-β protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature. 2006;440:352–357. doi: 10.1038/nature04533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cleary JP, et al. Natural oligomers of the amyloid-β protein specifically disrupt cognitive function. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:79–84. doi: 10.1038/nn1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Q, Walsh DM, Rowan MJ, Selkoe DJ, Anwyl R. Block of long-term potentiation by naturally secreted and synthetic amyloid β-peptide in hippocampal slices is mediated via activation of the kinases c-Jun N-terminal kinase, cyclin-dependent kinase 5, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase as well as metabotropic glutamate receptor type 5. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:3370–3378. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1633-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li S, et al. Soluble oligomers of amyloid β protein facilitate hippocampal long-term depression by disrupting neuronal glutamate uptake. Neuron. 2009;62:788–801. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terry RD, et al. Physical basis of cognitive alterations in Alzheimer’s disease: synapse loss is the major correlate of cognitive impairment. Ann. Neurol. 1991;30:572–580. doi: 10.1002/ana.410300410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeKosky ST, Scheff SW. Synapse loss in frontal cortex biopsies in Alzheimer’s disease: correlation with cognitive severity. Ann. Neurol. 1990;27:457–464. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mucke L, et al. High-level neuronal expression of Aβ1–42 in wild-type human amyloid protein precursor transgenic mice: synaptotoxicity without plaque formation. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:4050–4058. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04050.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei W, et al. Amyloid beta from axons and dendrites reduces local spine number and plasticity. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13:190–196. doi: 10.1038/nn.2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kang JE, et al. Amyloid-beta dynamics are regulated by orexin and the sleep-wake cycle. Science. 2009;326:1005–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.1180962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mackenzie IR, Miller LA. Senile plaques in temporal lobe epilepsy. Acta Neuropathol. 1994;87:504–510. doi: 10.1007/BF00294177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abramov E, et al. Amyloid-β as a positive endogenous regulator of release probability at hippocampal synapses. Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:1567–1576. doi: 10.1038/nn.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Puzzo D, et al. Picomolar amyloid-beta positively modulates synaptic plasticity and memory in hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:14537–14545. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2692-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dineley KT, Bell KA, Bui D, Sweatt JD. β-amyloid peptide activates α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:25056–25061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seabrook GR, et al. Mechanisms contributing to the deficits in hippocampal synaptic plasticity in mice lacking amyloid precursor protein. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:349–359. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00204-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saura CA, et al. Loss of presenilin function causes impairments of memory and synaptic plasticity followed by age-dependent neurodegeneration. Neuron. 2004;42:23–36. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laird FM, et al. BACE1, a major determinant of selective vulnerability of the brain to amyloid-beta amyloidogenesis, is essential for cognitive, emotional, and synaptic functions. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:11693–11709. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2766-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kullmann DM, Lamsa KP. Long-term synaptic plasticity in hippocampal interneurons. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:687–699. doi: 10.1038/nrn2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim JH, Anwyl R, Suh YH, Djamgoz MB, Rowan MJ. Use-dependent effects of amyloidogenic fragments of β-amyloid precursor protein on synaptic plasticity in rat hippocampus in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:1327–1333. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01327.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Snyder EM, et al. Regulation of NMDA receptor trafficking by amyloid-β. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:1051–1058. doi: 10.1038/nn1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu L, et al. Role of NMDA receptor subtypes in governing the direction of hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Science. 2004;304:1021–1024. doi: 10.1126/science.1096615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tackenberg C, Brandt R. Divergent pathways mediate spine alterations and cell death induced by amyloid-beta, wild-type tau, and R406W tau. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:14439–14450. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3590-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palop JJ, Chin J, Mucke L. A network dysfunction perspective on neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2006;443:768–773. doi: 10.1038/nature05289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leonard AS, McNamara JO. Does epileptiform activity contribute to cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease? Neuron. 2007;55:677–678. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Palop JJ, et al. Neuronal depletion of calcium-dependent proteins in the dentate gyrus is tightly linked to Alzheimer’s disease-related cognitive deficits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:9572–9577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1133381100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meilandt WJ, et al. Enkephalin elevations contribute to neuronal and behavioral impairments in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:5007–5017. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0590-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Minkeviciene R, et al. Amyloid beta-induced neuronal hyperexcitability triggers progressive epilepsy. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:3453–3462. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5215-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lalonde R, Dumont M, Staufenbiel M, Strazielle C. Neurobehavioral characterization of APP23 transgenic mice with the SHIRPA primary screen. Behav. Brain Res. 2005;157:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kumar-Singh S, et al. Behavioral disturbances without amyloid deposits in mice overexpressing human amyloid precursor protein with Flemish (A692G) or Dutch (E693Q) mutation. Neurobiol. Dis. 2000;7:9–22. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1999.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chin J, et al. Fyn kinase induces synaptic and cognitive impairments in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:9694–9703. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2980-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roberson ED, et al. Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates amyloid β-induced deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Science. 2007;316:750–754. doi: 10.1126/science.1141736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Amatniek JC, et al. Incidence and predictors of seizures in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Epilepsia. 2006;47:867–872. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Larner AJ, Doran M. Clinical phenotypic heterogeneity of Alzheimer’s disease associated with mutations of the presenilin-1 gene. J. Neurol. 2006;253:139–158. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Snider BJ, et al. Novel presenilin 1 mutation (S170F) causing Alzheimer disease with Lewy bodies in the third decade of life. Arch. Neurol. 2005;62:1821–1830. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.12.1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cabrejo L, et al. Phenotype associated with APP duplication in five families. Brain. 2006;129:2966–2976. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jayadev S, et al. Alzheimer’s disease phenotypes and genotypes associated with mutations in presenilin 2. Brain. 2010;133:1143–1154. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lai F, Williams RS. A prospective study of Alzheimer disease in Down syndrome. Arch. Neurol. 1989;46:849–853. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520440031017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Buckner RL, et al. Molecular, structural, and functional characterization of Alzheimer’s disease: evidence for a relationship between default activity, amyloid, and memory. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:7709–7717. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2177-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Henry TR, Votaw JR. The role of positron emission tomography with [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose in the evaluation of the epilepsies. Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am. 2004;14:517–535. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li G, et al. GABAergic interneuron dysfunction impairs hippocampal neurogenesis in adult apolipoprotein E4 knockin mice. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:634–645. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang L, Wang Z, Wang B, Justice NJ, Zheng H. Amyloid precursor protein regulates Cav1.2 L-type calcium channel levels and function to influence GABAergic short-term plasticity. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:15660–15668. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4104-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fellin T, et al. Neuronal synchrony mediated by astrocytic glutamate through activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors. Neuron. 2004;43:729–743. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Perea G, Araque A. Astrocytes potentiate transmitter release at single hippocampal synapses. Science. 2007;317:1083–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1144640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kuchibhotla KV, Lattarulo CR, Hyman BT, Bacskai BJ. Synchronous hyperactivity and intercellular calcium waves in astrocytes in Alzheimer mice. Science. 2009;323:1211–1215. doi: 10.1126/science.1169096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vezzani A, Granata T. Brain inflammation in epilepsy: experimental and clinical evidence. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1724–1743. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Origlia N, Arancio O, Domenici L, Yan SS. MAPK, beta-amyloid and synaptic dysfunction: the role of RAGE. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2009;9:1635–1645. doi: 10.1586/ern.09.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lauren J, Gimbel DA, Nygaard HB, Gilbert JW, Strittmatter SM. Cellular prion protein mediates impairment of synaptic plasticity by amyloid-beta oligomers. Nature. 2009;457:1128–1132. doi: 10.1038/nature07761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhu YJ, Lin H, Lal R. Fresh and nonfibrillar amyloid β protein (1–40) induces rapid cellular degeneration in aged human fibroblasts: evidence for AβP-channel-mediated cellular toxicity. FASEB J. 2000;14:1244–1254. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.9.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kayed R, et al. Annular protofibrils are a structurally and functionally distinct type of amyloid oligomer. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:4230–4237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808591200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Palop JJ, et al. Vulnerability of dentate granule cells to disruption of Arc expression in human amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:9686–9693. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2829-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Klaassen A, et al. Seizures and enhanced cortical GABAergic inhibition in two mouse models of human autosomal dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:19152–19157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608215103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]