Abstract

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) was first recognized in 2004 as a distinct, clinically relevant molecular subset of lung cancer. The disease has been the subject of intensive research at both the basic scientific and clinical levels, becoming a paradigm for how to understand and treat oncogene-driven carcinomas. Although patients with EGFR-mutant tumours have increased sensitivity to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), primary and acquired resistance to these agents remains a major clinical problem. This Review summarizes recent developments aimed at treating and ultimately curing the disease.

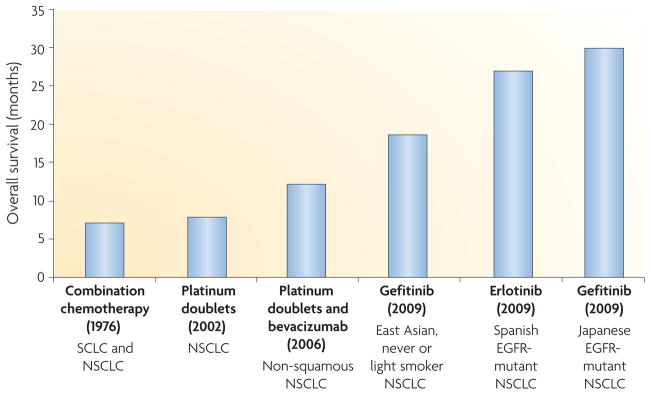

Cancers of the lung, the leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States, accounted for 30% of all male cancer deaths and 26% of all female cancer deaths in 2009 (REF. 1). The overall 5-year survival rate of patients with metastatic disease remains less than 15%2. However, emerging data suggest that considerable progress has been made in the treatment of subsets of patients with lung cancer (FIG. 1). Lessons from these patients can hopefully serve as a model for how to make advances against the entire disease.

Figure 1. Progress in the treatment of metastatic lung cancer.

In 1976, a chemotherapy trial studied all patients with lung cancer, regardless of whether they had small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) or non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC)3. In 2002, a landmark chemotherapy trial involving platinum doublets studied all patients with NSCLC, regardless of histological subtype (adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and large-cell carcinoma)152. In 2006, bevacizumab (Avastin; Genentech/ Roche) was shown to confer an overall survival benefit when added to chemotherapy for patients with non-squamous NSCLC153. The smoking history of patients was not recorded. In 2009, trials in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-mutant lung cancer with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) demonstrated the longest survival rates currently seen for NSCLC20,21,47. Notably, patients with EGFR-mutant lung tumours also have a better prognosis in the absence of therapy compared with those with EGFR-wild-type tumours20.

Historically, lung cancer was considered as one entity arising from the lung. In the mid-1970s, investigators showed that different histological subtypes had differential sensitivities to chemotherapeutic agents3. The trend towards subdividing lung cancer into ever more meaningful clinically relevant subsets has continued, with the appreciation that there are major histological differences among the main lung cancer subtypes, including small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which is comprised of adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and large-cell carcinoma. Today, further subcategorization is fuelled by the realization that tumours can be defined by various molecular criteria. One of the most promising treatment strategies exploits the discovery that distinct subsets of cancers harbour specific driver mutations in genes that encode signalling proteins that are crucial for cellular proliferation and survival. Targeting the activity of these mutant proteins can lead to cell death and therapeutic benefit. This finding serves as the basis for the concept of oncogene addiction4, implying that tumours have Achilles heels that can be targeted with specific agents.

This Review focuses on one particular molecularly defined subset of NSCLC that harbours activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene. EGFR belongs to a family of receptor tyrosine kinases (TKs) that includes EGFR, ERBB2 (also known as HER2), ERBB3 (also known as HER3) and ERBB4 (also known as HER4). Structurally, each receptor is composed of an extracellular ligand-binding domain, a transmembrane domain and an intracellular domain. All family members have intrinsic TK activity, except ERBB3. The receptors exist as inactive monomers. On binding to ligands, such as EGF and transforming growth factor-α, the receptors undergo conformational changes that facilitate homodimerization or heterodimerization. Growth factor-induced receptor dimerization of EGFR is followed by intermolecular autophosphorylation of key tyrosine residues in the activation loop of catalytic TK domains through the transfer of γ-phosphates from bound adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Subsequently, appropriate adaptor or signalling molecules with SRC homology 2 and protein tyrosine-binding domains bind to carboxy-terminal phosphotyrosines and recruit proteins involved in downstream signalling events that control multiple cellular processes, including proliferation and survival5. Selective blockade of EGFR and ERBB2 has been shown to be an effective therapeutic approach against multiple epithelial cancers.

EGFR-mutant tumours were first discovered in 2004 and currently represent the best-studied example of oncogene addiction in lung cancer. EGFR-mutant tumours most often display adenocarcinoma histology and are associated with a better prognosis than EGFR wild-type tumours6. After more than 30 years, during which the overall survival (OS) of patients with metastatic lung cancer remained at no more than 1 year, recent data have shown that patients with metastatic EGFR-mutant tumours treated with first-generation EGFR TK inhibitors (TKIs) can have a median survival of more than 2 years (FIG. 1). Unfortunately, primary resistance to TKIs is still observed and acquired resistance limits the prolonged effectiveness of currently available TKIs. Here, we discuss recent strategies aimed at targeting mutant EGFR with an emphasis on approaches to overcome resistance to TKIs.

First-generation anti-EGFR therapy

The rationale for targeting EGFR in cancer has been extensively reviewed5. Notably, the first-generation anti-EGFR therapies developed in the 1990s were all directed against the wild-type receptor, which was shown to be overexpressed in many epithelial cancer types. Therapeutic agents include the small molecule TKIs gefitinib (Iressa; AstraZeneca) and erlotinib (Tarceva; Genentech/OSI Pharmaceuticals) and the EGFR-specific antibody cetuximab (Erbitux; ImClone/ Merck/Bristol–Myers Squibb).

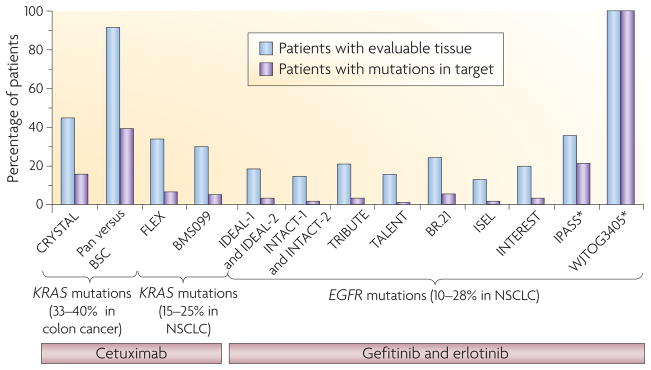

During the development of the first EGFR TKI, gefitinib, investigators worldwide noted that strikingly ten of 100 patients with previously heavily treated NSCLC had objective radiographic responses7–10. In confirmatory Phase II studies11,12 (TABLE 1), the major clinical characteristics of responding patients were found to be adenocarcinoma histology, East Asian ethnicity, a history of never smoking cigarettes and female gender12,13. In 2004, EGFR kinase domain mutations were discovered, found to be associated with the clinical characteristics of responding patients and linked to an increased sensitivity of lung tumours to gefitinib and the related compound, erlotinib14–16. Scepticism surrounding this link was fuelled by multiple inconclusive correlative studies of large clinical trials. In most of these studies, the percentage of tumours that could be evaluated for mutations and the proportion of mutant tumours among entire cohorts was extremely low (FIG. 2). The reasons for such poor tumour accrual include the retrospective nature of these studies and the fact that, in the absence of specific tissue requirements, most of the patients diagnosed with advanced and/or metastatic NSCLC had insufficient tissue for molecular analysis (FIG. 2).

Table 1.

select clinical trials in lung cancer involving anti-EGFR therapies

| Trial | Type | Drugs | enrollment criteria | rr (%) (EGFR TKI versus other) | Median time to treatment failure (months) (EGFR TKI versus other therapy) | refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gefitinib | ||||||

| IDEAL-1, IDEAL-2 | Phase II | Gefitinib (250 mg versus 500 mg) | Unselected previously treated NSCLC | 18.4–19.0 (IDEAL-1) and 9–12 (IDEAL-2) | 2.7–2.8 (IDEAL-1) and 1.5–1.7 (IDEAL-2) | 11, 12 |

| ISEL | Phase III | Gefitinib versus placebo | Unselected previously treated NSCLC | 8.0 versus 1.3 | 3.0 versus 2.6 | 19 |

| INTACT-1, INTACT-2 | Phase III | Chemotherapy ± gefitinib (250 mg versus 500 mg) | Unselected chemotherapy-naive NSCLC | 50.3–51.2 versus 47.2 (INTACT-1) and 30 versus 28.7 (INTACT-2) | 5.5–5.8 versus 6.0 (INTACT-1) and 4.6–5.3 versus 5.0 (INTACT-2) | 168, 169 |

| INTEREST | Phase III | Gefitinib versus docetaxel | Unselected previously treated NSCLC | 9.1 versus 7.6 | 2.2 versus 2.2 | 157 |

| IPASS | Phase III | Gefitinib versus chemotherapy | East Asian never or light smokers with chemotherapy-naive lung adenocarcinoma | 43.0 versus 32.2* 71.2 versus 47.3‡ |

5.7 versus 5.8* 9.5 versus 6.3‡ |

20 |

| WJTOG3405 | Phase III | Gefitinib versus chemotherapy | Japanese EGFR-mutant chemotherapy-naive NSCLC | 62.1 versus 32.2 | 9.2 versus 6.3 | 21 |

| NEJ002 | Phase III | Gefitinib versus chemotherapy | Japanese EGFR-mutant chemotherapy-naive NSCLC | 73.7 versus 30.7 | 10.8 versus 5.4 | 24 |

| Erlotinib | ||||||

| NA | Phase II | Erlotinib | NSCLC with BAC features | 22 | 4 | 13 |

| BR.21 | Phase III | Erlotinib versus placebo | Unselected previously treated NSCLC | 8.9 versus <1 | 2.2 versus 1.8 | 18 |

| TALENT | Phase III | Chemotherapy ± erlotinib | Unselected chemotherapy-naive NSCLC | 31.5 versus 29.9 | 6.4 versus 6.0 | 158 |

| TRIBUTE | Phase III | Chemotherapy ± erlotinib | Unselected chemotherapy-naive NSCLC | 21.5 versus 19.3 | 5.1 versus 4.9 | 170 |

| SLCG | Single arm | Erlotinib | Spanish EGFR-mutant NSCLC | 70.6 | 14 | 23 |

| Cetuximab | ||||||

| FLEX | Phase III | Chemotherapy ± cetuximab | EGFR IHC-positive chemotherapy-naive NSCLC | 36 versus 29 | 4.8 versus 4.8 | 171 |

| BMS099 | Phase III | Chemotherapy ± cetuximab | Unselected chemotherapy-naive NSCLC | 25.7 versus 17.2 | 4.4 versus 4.2 | 49 |

BAC, bronchioloalveolar carcinoma; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; IHC, immunohistochemistry; NA, not applicable; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; RR, response rate; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Statistic for the entire population.

Statistic for the patients only with EGFR-mutant tumours.

Figure 2. Tissue accrual across multiple trials.

Trials in colon cancer (left side of graph), in which KRAS mutations are observed in 33–40% of tumour samples, were highly efficient at collecting tissue samples (45–92% patients had suitable tissue available for molecular analyses and 16–40% of patients had KRAS mutations). Based on the poor responses observed in patients with KRAS-mutant tumours, the KRAS biomarker was easily found to be a negative predictor of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) therapy (for example, cetuximab and panitumumab (Vectibix; Amgen) efficacy154,155). By contrast, in lung cancer, the role of KRAS mutations (FLEX and BMSO99 trials) could not be accurately determined in trials with cetuximab. The prevalence of KRAS mutations is 15–25%, only 30–34% of patients had tissue available for analysis and only 5–6% of patients had KRAS mutations47,49. Similarly, study of the role of EGFR mutations has been hampered by low tissue accrual (right section of the graph). EGFR mutations are found in 10–28% of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), but tissue accrual in the major trials involving EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (IDEAL-1, IDEAL-2, INTACT-1, INTACT-2, TRIBUTE, TALENT, BR.21, ISEL and INTEREST) was < 24% (blue bars)20,21,34,156–160. Of the patients with available tumour samples, the percentage that harboured an EGFR mutation (purple bars) was <5%, making it difficult to draw conclusions. However, in IPASS and WJTOG3405, in which these percentages were much higher, EGFR mutations were readily found to be a positive predictor of benefit. BSC, best supportive care; Pan, panitumumab. *Represents clinically enriched trials.

In the past 5 years, however, at least nine prospective single-arm studies for patients with advanced NSCLC and activating EGFR mutations have validated the benefit of EGFR TKIs in EGFR-mutant lung cancer (reviewed in REF. 17). Trials were performed in East Asia, the United States and Europe, with either gefitinib or erlotinib. Radiographic response rates (RRs) ranged from 55% to 91%, and progression-free survival (PFS) and time to progression (TTP) from 7.7 months to 13.3 months. For comparison, RRs in unselected patients with NSCLC who were treated with gefitinib and erlotinib were 8.0% to 8.9%, with a median TTP of 2.2 months to 3.0 months in two large studies18,19 (TABLE 1).

In 2009, two landmark randomized prospective Phase III studies (the Iressa Pan-Asia Study (IPASS) and WJTOG3405) showed that an EGFR TKI is superior to chemotherapy as an initial treatment for EGFR-mutant lung cancer20,21 (TABLE 1). The IPASS enrolled East Asian individuals who had never smoked (never smokers) or former light smokers with lung adenocarcinoma. The PFS of patients with EGFR-mutant tumours was significantly longer among those who received gefitinib than among those who received carboplatin–paclitaxel (hazard ratio (HR) for progression or death, 0.48; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.36–0.64; p < 0.001), whereas the PFS of patients with wild-type EGFR tumours was significantly longer among those who received chemotherapy (HR for progression or death with gefitinib, 2.85; 95% CI, 2.05–3.98). In the WJTOG3405 study, which enrolled Japanese patients with lung tumours harbouring EGFR mutations, the gefitinib group also had a significantly longer median PFS of 9.2 months (95% CI, 8.0–13.9) compared with 6.3 months (95% CI, 5.8–7.8; HR, 0.489; 95% CI, 0.336–0.710; log-rank p < 0.0001) in the cisplatin plus docetaxel group. Erlotinib has similarly been shown to be highly effective in patients with EGFR-mutant tumours22,23. A summary of major trials with anti-EGFR therapies is listed in TABLE 1.

More recently, another randomized prospective Phase III study (NEJ002) in patients with untreated EGFR-mutant tumours confirmed the benefit of first-line EGFR TKI (gefitinib) versus chemotherapy and further hinted that the order of treatment is important24. Unlike previous studies, 95% of the patients whose disease progressed on first-line carboplatin–paclitaxel crossed over to gefitinib therapy. Strikingly, the median OS in the gefitinib group was 7 months longer than that in the chemotherapy group (30.5 months versus 23.6 months). Moreover, the rate of response to gefitinib was slightly worse in the second-line setting than in the first-line setting (58.5% versus 73.7%). To determine whether EGFR TKIs are truly more effective in the first-line versus the second-line setting further studies are warranted.

A small proportion (1–20%, depending on the trial) of patients with no detectable EGFR-activating mutations show a radiographic response when treated with EGFR TKIs20,25,26. This observation can be partly explained by the fact that all molecular diagnostic tests for EGFR mutations have an inherent limit of detection27. However, it is possible that other genetic alterations may activate the EGFR signalling pathway in the absence of intrinsic gene mutations. For example, disease in patients with mucoepidermoid carcinomas (MECs) of the salivary and bronchial glands with wild-type EGFR has responded to gefitinib28,29, and MEC cell lines are sensitive to EGFR TKIs in vitro30. As MECs harbour a recurrent mucoepidermoid carcinoma translocated 1 (MECT1)–mastermind-like 2 (MAML2) fusion31 that induces expression of the EGFR ligand amphiregulin30, one possibility is that gefitinib sensitivity is mediated by the action of the aberrant fusion protein.

Other predictive beneficial biomarkers have been proposed for EGFR TKIs, notably EGFR expression measured by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and EGFR copy number assessed by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH)32–37. Although EGFR IHC has not been found to be informative, increased EGFR copy number (that is, high polysomy and gene amplification) was shown to be associated with OS benefit in retrospective studies32–34,36. However, prospective studies have not validated EGFR FISH as a useful biomarker.

Whether erlotinib and gefitinib can be considered equally efficacious in the first-line setting relative to chemotherapy is currently unknown. Although no direct comparative effectiveness trials exist that have compared gefitinib with erlotinib in patients with EGFR-mutant tumours, the data suggest that there are no major differences between them. The two drugs are dosed differently (that is, erlotinib is administered at its maximum-tolerated dose whereas gefitinib is not); however, both EGFR inhibitors have similar, strongly correlated inhibitory patterns in EGFR-mutated cells in vitro38,39. In patients, the major mechanisms of primary and acquired resistance (see below) are the same for both drugs40,41, indicating that they have the same target. Finally, similar response, PFS and survival rates have been observed for erlotinib and gefitinib21,22,42.

In contrast to the link between EGFR mutations and EGFR TKIs, the role of EGFR mutations in predicting sensitivity to EGFR-specific antibodies is not clear. Cetuximab is a human–murine chimeric IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds to the extracellular domain of EGFR and blocks EGFR signalling43. The antibody has been US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for the treatment of colorectal and head and neck cancers44,45 but its role in NSCLC remains to be established. A single-arm study in unselected patients with previously treated disease showed a RR of only 4.5%46 and, despite cetuximab showing a promising additive effect with chemotherapy47, two Phase III studies (FLEX and BMS099) in chemotherapy-naive patients showed conflicting results regarding OS48,49 (TABLE 1). No links between EGFR mutations and sensitivity to cetuximab have been found, although only a limited number of patients has been studied50,51. As cetuximab interferes with EGFR ligand binding and subsequent receptor dimerization, EGFR mutations that confer ligand independence may abrogate the efficacy of this agent52. Interestingly, in mouse models of lung cancer driven by EGFR-L858R (exon 21), cetuximab can induce dramatic tumour regressions53,54 but the drug is not effective as a single agent against an exon 19 deletion53 or T790M mutant54 (see below). The reasons for this discrepancy are unknown and might be related to different structural or conformational properties of the different mutants.

Biology of EGFR mutations

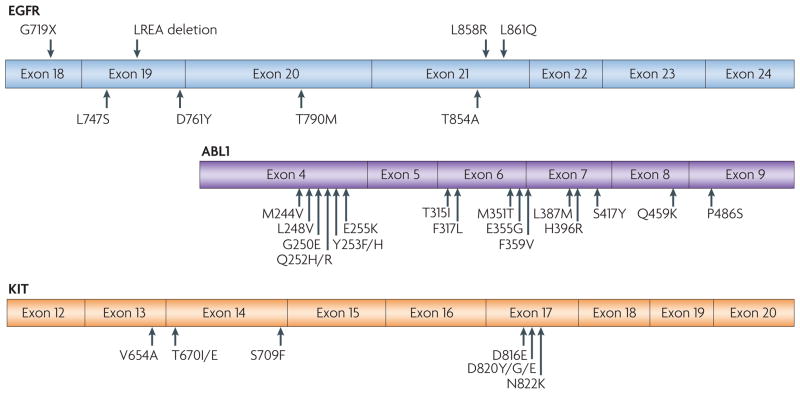

In lung cancer, activating mutations in EGFR occur in exons encoding the kinase domain (exons 18 to 21; summarized in FIG. 3). EGFR mutations are usually heterozygous, with the mutant allele also showing gene amplification55,56. Multiple genomic studies have shown that EGFR-mutant NSCLCs represent distinct disease phenotypes that have unique expression, mutation and copy number signatures57–59. For example, EGFR-mutant NSCLCs rarely harbour serine/threonine kinase 11 (STK11; also known as LKB1) mutations and are associated with a concurrent loss of the negative regulatory dual specificity phosphatase 4 (DUSP4) and the tumour suppressor cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A; which encodes p16) genes59.

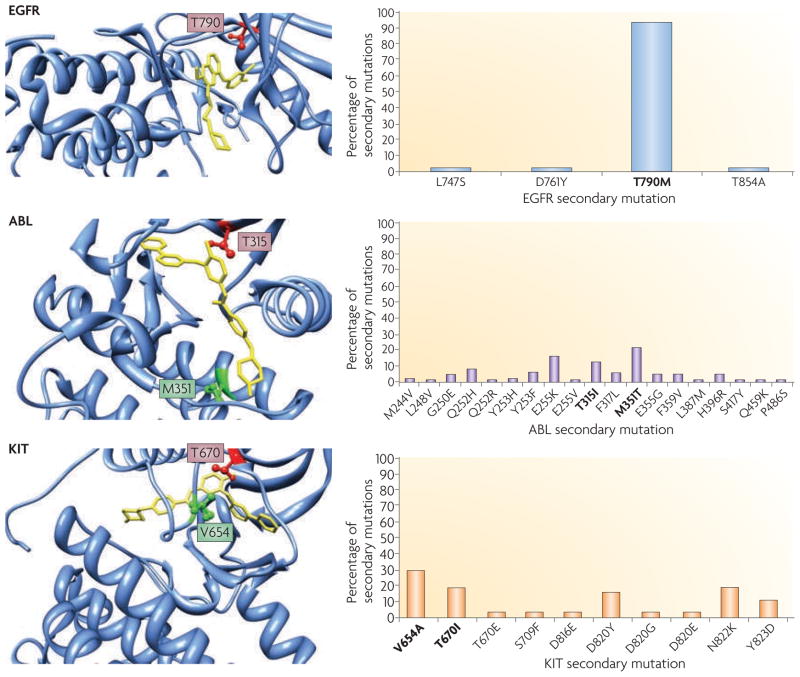

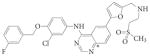

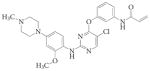

Figure 3. Comparison of TKI-sensitive and TKI-resistant mutations in cancer-derived mutant TKs.

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-mutant lung cancer, breakpoint cluster region (BCR)–ABL-driven chronic myelogenous leukaemia (CML) and KIT-mutant gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) have all been treated effectively with specific tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs); that is, gefitinib or erlotinib for lung cancer, imatinib for CML and imatinib for GIST. Activating drug-sensitive mutations are shown on the top of EGFR. TKI-resistant mutations are depicted on the bottom of each kinase domain schematic. The most common activating mutations in EGFR are a point mutation in exon 21, which substitutes an arginine for a leucine (L858R), and a small deletion in exon 19 that removes four amino acids (LREA). Together, these genomic changes account for ~90% of TKI-sensitive mutations that are observed in EGFR-mutant tumours. Other major drug-sensitive mutations include G719X (encoded by exon 18) and L861Q (exon 21).

The crystal structures of the L858R and G719S TKI-sensitive EGFR mutants show that these substitutions activate the kinase through disruption of autoinhibitory interactions, resulting in receptors with 50-fold more activity compared with their wild-type counterparts60–62. A separate crystal structure suggests the presence of an activating region in the juxtamembrane domain of EGFR63. To date, the crystal structure of the exon 19 deletion EGFR mutant has not been determined. Biochemical data further show enhanced kinase activity and transformation capabilities of EGFR in the presence of L858R or the exon 19 deletion64,65. In contrast to wild-type EGFR, the presence of a TKI-sensitive mutation results in preferential binding of gefitinib or erlotinib versus ATP.

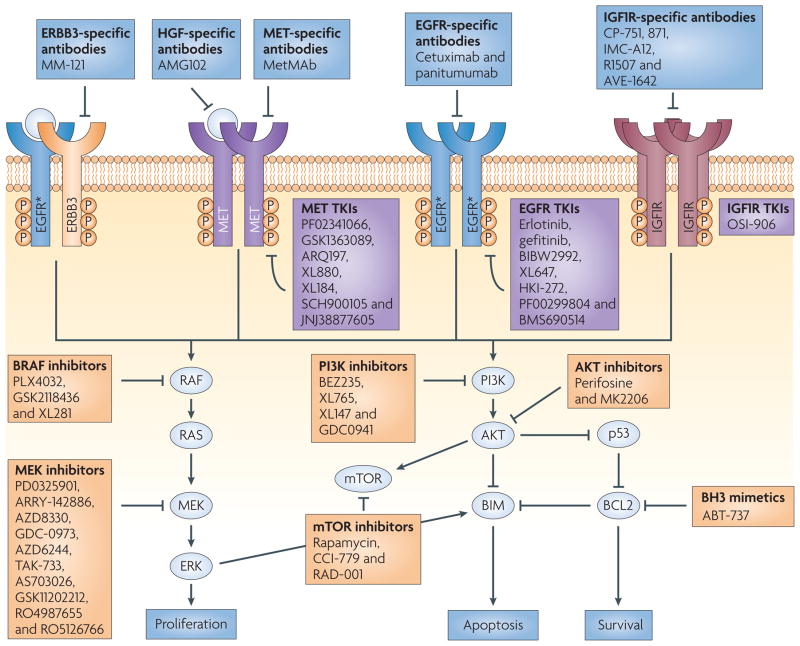

As EGFR-mutant NSCLC cells are dependent on this aberrant kinase signalling for survival, inhibition of this pathway with the TKIs erlotinib and gefitinib results in cell death that is mediated through the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. This process is dependent on BIM, a BCL-2 pro-apoptotic family member regulated by ERK signalling66–69 (FIG. 4). The downregulation of the induced myeloid leukaemia cell differentiation 1 (MCL1) protein — an anti-apoptotic protein regulated by PI3K signalling — also seems to be important70.

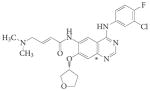

Figure 4. Multi-pathway inhibition as a strategy to treat EGFR-mutant NSCLC.

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutants (starred) propagate signals through the PI3K–AKT and ERK pathways. Cross-activation of other membrane-bound receptor tyrosine kinases occurs under tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI)-sensitive states and following the development of acquired resistance (arrows). The boxes depict a sample of the targeted agents available for the treatment of the disease at various stages (see FIG. 6 for more details). IGF1R, insulin-like growth factor receptor 1; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; P, phosphorylation.

One area of contention is whether EGFR-mutant tumours display similar biological characteristics in both East Asian and Caucasian patients. Currently, no convincing data exist to suggest that there are major differences between these two groups of patients. At the molecular level, the sequences of exons encoding a portion of the kinase domain (exons 18 to 21) from Asians and non-Asians and the range of the major drug-sensitive mutations are grossly similar (for example, see REF. 71 and FIG. 3). In preclinical models, transgenic mouse lung tumours harbouring EGFR-L858R or an exon 19-deletion mutant similarly respond to TKIs regardless of whether the mutation is on a mixed genetic (B6×CBA×FVB) background72 or on a pure (FVB) background53, indicating that genetic background does not substantially affect drug sensitivity. Clinically, the prognostic value of the EGFR mutation in patients undergoing surgery is approximately the same in Japan and the United States6,73. The RRs and survival rates are remarkably similar across populations21,42. Finally, the major mechanisms of acquired resistance in patients (see below) are the same in East Asian and Caucasian populations40,41.

Primary resistance to EGFR TKIs

Lung tumours can show de novo resistance (primary resistance) to TKI therapy, even in the presence of an activating mutation in EGFR. Recent work has uncovered many of the molecular mechanisms underlying this primary resistance.

TKI resistance in the presence of an EGFR mutation

Among patients with EGFR-mutant tumours, a 75% RR is observed, indicating that approximately 25% of cases do not respond to a TKI (compared with 90% of unselected patients with NSCLC). Some of this can be explained by the fact that patients may experience tumour shrinkage, but the reduction in tumour size is not sufficient to fulfil response evaluation criteria in solid tumours (RECIST)74. According to these criteria, the unidimensional measurement of a tumour must shrink by 30% or more to be counted as a partial response. Tumour shrinkage of 20–25% may be beneficial to patients, but would only be considered as ‘stable disease’ by these guidelines.

Drug-resistant EGFR mutations

Some EGFR mutations, although they occur in exons 18 to 21, are associated with primary resistance to EGFR TKIs (FIG. 3). For example, small insertions or duplications in exon 20 (such as D770_N771, ins NPG, ins SVQ, insG and N771T; see REF. 75 for a complete list of insertions) are observed in ~5% of NSCLCs. In vitro studies have shown that such mutations are less sensitive to EGFR TKIs than the exon 19 deletion and L858R mutants76. Consistent with these data, most patients with tumours harbouring exon 20 insertions show progressive disease while taking EGFR TKIs75. Similarly, some patients present with a de novo resistance T790M mutation, which is encoded by exon 20 (REFS 77–79). As this mutation is more commonly found in patients with acquired resistance, the data are discussed in more detail below.

Primary TKI resistance may also be mediated by other rarer mutations in EGFR that occur together with drug-sensitive mutations (FIG. 3). For example, the drug-sensitive G719C mutation14 can co-occur de novo with an E709A mutation80. In vitro, the double-mutant receptor has been shown to be less sensitive to EGFR drugs than the G719C mutant alone81.

Other genomic alterations that co-occur with EGFR mutations

Another reason why tumours with drug-sensitive EGFR mutations may not respond to treatment with EGFR inhibitors is the presence of other genetic lesions that affect signalling downstream of EGFR. For example, mutations in PIK3CA, the p110α catalytic subunit of PI3K, are found in approximately 2% of NSCLCs and can co-occur with EGFR mutations82. The addition of a constitutively active PI3K mutant (E545K) has been shown to confer gefitinib resistance, at least in vitro83. Similarly, loss of PTEN expression in EGFR-mutant cells correlates with decreased sensitivity to EGFR TKIs84. PTEN loss in NSCLC cells, although rare (<5%), uncouples EGFR from negative-feedback mechanisms, resulting in decreased degradation mediated by CBL, an E3 ubiquitin protein ligase that targets molecules for proteasomal destruction84,85.

Crosstalk between EGFR and insulin-like growth factor receptor 1 (IGF1R) has also been implicated as a potential mechanism of disease persistence in EGFR-mutant cell line models86,87 (FIG. 4). For example, some EGFR-mutant cells undergo only G1 cell cycle phase arrest in the presence of erlotinib, but undergo apoptosis when co-treated with an IGF1R-specific antibody87. In another study, EGFR-mutant NSCLC cells persisting after treatment with gefitinib gave rise to populations of cells of mixed sensitivity86. After further investigation, these persistent cells showed a distinct chromatin state that was mediated through IGF1R signalling and the histone demethylase, lysine-specific demethylase 5A (KDM5A)86.

Resistance in EGFR-wild-type tumours

The IPASS clinical trial demonstrated that most tumours without detectable EGFR kinase domain mutations are insensitive to gefitinib20. Tumours wild-type for EGFR often harbour somatic mutations in other genes encoding signalling molecules. Thus, primary drug insensitivity is linked to the absence of drug-sensitizing mutations in EGFR and is more likely to be a result of mutations in other genes. Activating mutations occurring at codons 12 and 13 in the GTPase domain of KRAS are observed in 15–25% of NSCLCs and occur almost only in EGFR-wild-type tumours. KRAS mutations are found more frequently in tumours from former or current smokers compared with never smokers, and in tumours from Caucasians compared with East Asians, for reasons which are poorly understood. The initial observation that KRAS-mutant lung tumours are resistant to EGFR TKIs88 has been well validated89. However, although KRAS mutations are used routinely as a negative predictor of benefit from EGFR-specific antibody therapy in colorectal carcinoma (FIG. 2), KRAS mutation testing has not been widely adopted in lung cancer.

Approximately 2–3% of NSCLCs harbour mutations in BRAF, which encodes a signalling molecule downstream of EGFR90–92. Similar to KRAS mutations, BRAF mutations are also mutually exclusive with changes in EGFR. The most common change in BRAF, V600E, is found in a large subset of melanomas, colon and thyroid cancer91, and confers sensitivity to specific small-molecule V600E inhibitors93 as well as MEK inhibitors94. NSCLC cell lines harbouring BRAF V600E are also sensitive to the MEK inhibitor PD0325901 but are resistant to EGFR inhibition95. A Phase II MEK inhibitor trial with PD0325901 showed little efficacy in advanced NSCLC; however, patients were not preselected by mutation status96.

Another 5% of tumours harbour translocations in anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)97,98. So far, most of these oncogenic rearrangements involve the echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4 (EML4) as the 5′ partner of ALK. Multiple different EML4–ALK variants have been identified, but all involve the tyrosine kinase portion of ALK and have variable lengths of EML4 (REF. 99). Similar to KRAS- and BRAF-mutant tumours, most of ALK fusion-positive tumours lack other ‘driver’ mutations. Clinically, ALK fusion-positive tumours are insensitive to EGFR TKIs100.

Primary resistance to EGFR TKIs may also be mediated by non-mutation-based mechanisms. One example involves increased expression of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), the ligand for the MET receptor tyrosine kinase101. HGF binding increases MET-mediated activation of the PI3K–AKT pathway, decreasing the ability of an EGFR TKI to effectively inhibit this signalling cascade. In contrast to the role of MET in acquired resistance (see below), primary resistance owing to increased HGF activation of MET is channelled through GAB1, not ERBB3 (REFS 101,102).

Acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs

Until recently, the clinical definition of acquired resistance (secondary resistance) to EGFR TKIs in lung cancer was not uniform. To minimize reporting of false- positive and false-negative activity in clinical trials and to facilitate the identification of agents that truly overcome acquired resistance to gefitinib and erlotinib, the following clinical and molecular criteria were recently proposed to more precisely define acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs103: previous treatment with a single-agent EGFR TKI (for example, gefitinib or erlotinib); a tumour that harbours an EGFR mutation known to be associated with drug sensitivity and/or objective clinical benefit from treatment with an EGFR TKI; systemic progression of disease (by RECIST or radiological criteria put forth by the World Health Organization) while on continuous treatment with gefitinib or erlotinib within the past 30 days; and no intervening systemic therapy between the cessation of gefitinib or erlotinib and the initiation of new therapy. The relatively simple definition proposed should lead to a more uniform approach to investigating the problem of acquired resistance to EGFR.

Second-site EGFR mutations

Chronic myelogenous leukaemia (CML) cells harbouring ABL translocations and gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) cells harbouring activating KIT mutations are highly sensitive to the ABL and KIT inhibitor, imatinib (Gleevec; Novartis). When tumours relapse, a common mechanism of resistance is the emergence of second-site mutations in ABL and KIT104,105. A major secondary mutation involves a threo-nine gatekeeper residue in these proteins; the change to a bulkier isoleucine residue alters drug binding in both ABL (T315I) and KIT (T670I) (FIG. 5). Analogously, patients with EGFR-mutant tumours who develop acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs often develop a second-site mutation in the threonine gatekeeper residue at position 790, T790M. This mutation occurs exclusively in cis with the primary activating mutations in EGFR. Unlike CML and GIST, in which the gatekeeper mutation is found in 20–25% of patients with acquired resistance to imatinib, the T790M mutation in EGFR is found in 50% of EGFR-mutant tumours with acquired resistance to erlotinib or gefitinib106,107 (FIG. 5). One possible explanation for the discrepancy in the frequency of gatekeeper mutations is that imatinib binds to ABL and KIT in their inactive conformations, whereas gefitinib and erlotinib bind to EGFRs in their active conformations56 (TABLE 2). Therefore, any mutations that disrupt the inactive conformation of ABL or KIT can lead to imatinib resistance, whereas only mutations that interfere with drug binding in the EGFR ATP pocket may confer resistance to gefitinib and erlotinib.

Figure 5. Comparison of second-site mutation frequency following development of acquired resistance to TKI therapy.

All patients with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) will inevitably develop acquired resistance following treatment with the tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) gefitinib or erlotinib. In ~50% of cases, resistance is attributed to a second-site mutation in EGFR. The change of the gatekeeper threonine to a methionine (T790M) accounts for ~90% of secondary mutations observed in EGFR56,107,121. By contrast, second-site resistance mutations found in ABL and KIT following treatment with imatinib in chronic myelogenous leukaemia (CML) and gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST), respectively, are found across the kinase domain (see graphs on right side of figure). Mutations affecting the analogous gatekeeper residue in ABL (T315)161,162 and KIT (T670)163,164 are observed in less than 20% of cases. Gatekeeper residues are shown in red in the crystal structures. For ABL and KIT, the most common secondary mutation is shown in green. EGFR is shown crystallized with gefitinib (yellow); ABL and KIT were both crystallized with imatinib (yellow). Crystal structures were obtained from the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank (RCSB Data Bank; see Further information; accession numbers 2ITY (EGFR)60, 2HYY (ABL)165 and 1T46 (KIT)166). The structural graphics were produced using the University of California San Francisco (USCF) Chimera package167 (see Further information) from the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization and Informatics at the USCF, USA.

Table 2.

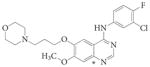

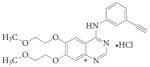

summary of current small-molecule EGFR inhibitors

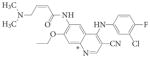

| Drug structure | Drug name | Generic name | Trade name | Company | Target | EGFR inhibition | Conformation | FDA approved | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reversible | |||||||||

|

ZD1839 | Gefitinib | Iressa | AstraZeneca | EGFR | Mut>T790M | Active | 172 | |

|

OSI-774 | Erlotinib | Tarceva | OSI/Genentech | EGFR | Mut>T790M | Active | NSCLC | 173 |

| XL647 | Exelixis/Symphony Evolution | EGFR, ERBB2, VEGFR and EPHB4 | Mut>T790M | 174 | |||||

| ZD6474 | Vandetanib | Zactima | AstraZeneca | EGFR and VEGFR | Mut>T790M | 175 | |||

|

GW572016 | Lapatinib | Tykerb | GlaxoSmithKline | EGFR and ERBB2 | Unknown | Inactive | Breast | 176 |

| Irreversible (bind covalently to C797) | |||||||||

|

EKB-569 | Pelitinib | Wyeth | EGFR | Mut>T790M | 177 | |||

| HKI-272 | Neratinib | Wyeth | EGFR and ERBB2 | Mut>T790M | 178 | ||||

|

BIBW2992 | Afatinib | Boehringer Ingelheim | EGFR and ERBB2 | Mut>T790M | 141 | |||

|

CI-1033 | Canertinib | Pfizer | pan-ERBB | Unknown | 179 | |||

| PF00299804 | Pfizer | pan-ERBB | Mut>T790M | 142 | |||||

|

WZ4002 | Gatekeeper Pharmaceuticals | EGFR | T790M>Mut | 147 | ||||

EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; EPHB4, ephrin type-B receptor 4; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; Mut, mutant EGFR (exon deletion or L858R); NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor; WT, wild-type EGFR.

Quinazoline cores.

The T790M mutation is almost never found in progressive brain or central nervous system lesions. This observation may be due to a lack of selective pressure, as the concentration of EGFR TKI that reaches the brain is 100-fold less than that found in blood108,109.

Rarely, T790M mutations can be found in the germ line of patients (0.54% of never smokers with lung cancer). This variant seems to be associated with increased genetic susceptibility to lung cancer, which usually occurs after the age of 50 (REFS 110–112). Tumours in these patients often contain an additional activating mutation in EGFR, suggesting that additional genetic events (such as other changes in EGFR) are required for tumorigenesis.

At least two molecular mechanisms explain how T790M confers drug resistance. First, substitution of a bulky methionine for threonine at position 790 leads to altered drug binding in the ATP pocket of EGFR. Second, introduction of the T790M mutation increases the ATP affinity of the EGFR-L858R mutant by more than an order of magnitude, in effect restoring ATP affinity back to the level of wild-type EGFR. This restoration closes the therapeutic window that is opened by the diminished ATP affinity of the oncogenic mutants, which are normally more easily inhibited relative to wild-type EGFR61,113.

Biochemical studies investigating the properties of T790M have shown synergistic kinase activity and transformation potential when the mutation is present in the context of an EGFR-sensitizing mutation64,65. However, despite this enhanced oncogenicity of T790M-harbouring EGFR, patients with this form of acquired resistance can display slow rates of disease progression114. Following the discontinuation of TKI therapy, disease flares have also been reported115, suggesting that a proportion of cells in a resistant tumour cell population remain sensitive to EGFR inhibition (discussed below). Although erlotinib and gefitinib have limited activity against tumours with T790M-harbouring EGFR67, multiple re-responses to EGFR TKIs following a short hiatus without targeted therapy have been reported115–119. The biology underlying this phenomenon has yet to be elucidated.

A recent study suggests that T790M-harbouring resistant clones may also be found at a very low frequency in untreated EGFR-mutant lung cancers. Using highly sensitive mutation detection techniques, EGFR T790M mutations were detected at an allele frequency of one in 500 in pretreatment tumour samples from patients with metastatic NSCLC77. Whether such mutations pre-exist in early-stage tumours has not yet been reported. One caveat, however, is that the polymerase chain reaction-based kit (DxS Ltd) used to detect the T790M mutations in this study has been associated with a high false-positive rate, leading the manufacturer to delete that mutation from its range. Thus, further studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Three other second-site mutations in EGFR have been associated with acquired resistance, including L747S (exon 19)120, D761Y (exon 19)56 and T854A (exon 21 in the activation loop)121 (FIGS 3,5). Like T790, T854 is a drug contact residue and mutation to the smaller hydrophobic alanine residue may increase the size of the selectivity pocket, negatively impacting erlotinib binding122. L747 occurs at the start of the loop between the β3 strand and the α-C helix and is thought to shift the equilibrium towards the active conformation of the receptor123. D761 occurs in the a-C helix and a salt bridge formed by D761 may be disrupted by mutation to tyrosine, affecting the catalytic cleft of the receptor124. Consistent with the clinical data, D761Y, T790M and T854A were all identified in a comprehensive resistance mutation screen with erlotinib in vitro122. Among the resistance mutations, T790M confers the highest degree of drug resistance.

MET amplification

Amplification of the MET oncogene is observed in up to 20% of EGFR-mutant NSCLCs after TKI failure, independently of the T790M mutation40,41. Cells with MET amplification seem to undergo a kinase switch and rely on MET signalling through the ERBB3 pathway to maintain activation of AKT through increased phosphorylation in the presence of EGFR TKIs (FIG. 4). In addition to its role in de novo resistance (discussed above), the MET ligand HGF can play a part in acquired resistance to TKIs101. In one study, tumour cells with MET amplification were detected at a low frequency using high-throughput FISH in four patients with untreated EGFR-mutant tumours who all developed acquired resistance to gefitinib or erlotinib through MET amplification102. By contrast, pre-existing amplification was found only rarely in tumours from patients (one of eight) who did not develop resistance by MET amplification. Collectively, these data suggest that TKI therapy may select for pre-existing cells with MET amplification.

Other mechanisms of acquired resistance

Tumours from approximately 40% of patients with acquired resistance do not harbour a second-site mutation or MET amplification. Thus, multiple investigations to identify resistance mechanisms are ongoing. One promising approach involves the study of acquired resistance in mouse models of EGFR TKI-sensitive lung tumours125. Prolonged exposure of mice harbouring EGFR-L858R-driven and exon 19 deletion-driven lung tumours led to the development of resistant tumours that harboured the secondary T790M change and/or Met amplification. Further analysis of these models may reveal novel mechanisms faster than by studying humans.

The epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) has been associated with resistance to EGFR TKIs in vitro126. Recently, investigators confirmed that EMT can also be found in patient tumours 127. The shift in signalling networks resulting from EMT may alleviate dependence on EGFR signalling128. Increased IGF1R signalling has also been associated with acquired resistance, albeit only in an in vitro model using a cell line that expressed high levels of wild-type EGFR129.

Another unexplained observation is that some patients originally diagnosed with EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma who develop acquired resistance display SCLC at the time of relapse. Three such cases have been reported130–132. In patients in whom the mechanisms of resistance have been examined, none displayed the T790M mutation or MET amplification, but tumours have been found to harbour EGFR drug-sensitizing mutations. This remains an area of active investigation.

Overcoming resistance to TKIs

Primary resistance

As stated above, primary resistance falls into four main categories: TKI resistance in the presence of a drug-sensitizing EGFR mutation; drug-resistant EGFR mutations; genomic alterations that co-occur with EGFR mutations; and EGFR-wild-type tumours. Different strategies are needed to overcome resistance for each category (FIGS 4,6).

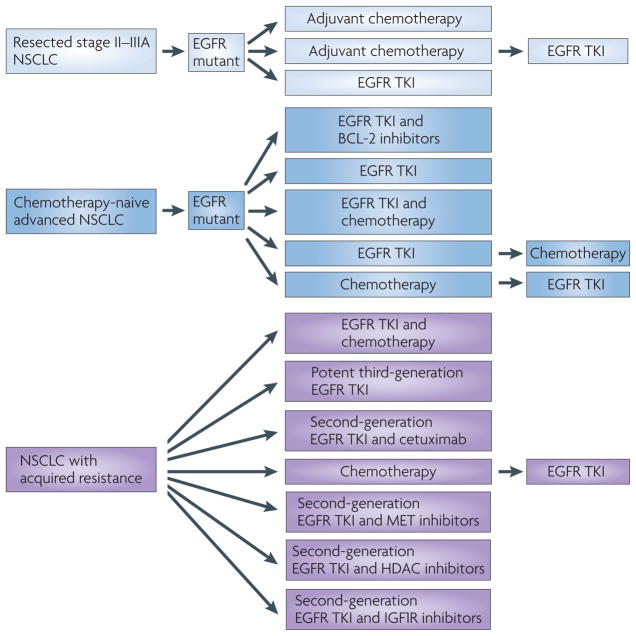

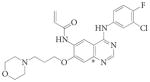

Figure 6. Potential treatment strategies to cure EGFR-mutant lung cancer.

The optimal treatment strategies for patients with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-mutant tumours that present with early-stage disease (pale blue, top), late-stage disease (blue, middle) and acquired resistance (purple, bottom) are an active area of investigation. Patients with resectable tumours may benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy, tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) or both in varying sequence of treatment. Patients with late-stage disease may benefit from combination therapy with a TKI, which may delay or prevent the emergence of acquired resistance. For example, agents targeting the apoptotic pathway combined with TKIs enhance cell death of EGFR-mutant cells in preclinical models66,68,69,123. Alternatively, the addition of chemotherapy before, after or concurrent with TKI treatment may induce a synergistic response. Finally, in the case of acquired resistance, continuation of the TKI in combination with various other agents may be the most beneficial strategy. However, the selection of additional therapies depends heavily on the molecular composition of the tumour and the mechanism of resistance. HDAC, histone deacetylase; IGF1R, insulin-like growth factor receptor 1; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer.

As the first category of resistance may be related to semantics (whether tumour shrinkage meets established radiographic criteria), this is not an active area of investigation. However, as the first-generation EGFR TKIs were originally developed against wild-type EGFR and EGFR mutations were only discovered after the initial development of these drugs, there is a rationale to pursue trials to determine the optimum upfront treatments for patients with tumours that harbour EGFR mutations (FIG. 6). One potential strategy involves taking advantage of the requirement for BIM and enhancing TKI-induced apoptosis by adding a BCL-2 inhibitor66 (FIG. 4). Such an approach, which seems promising in vitro, could lead to more profound responses and delayed TTP. For drug-resistant EGFR mutations, such as exon 20 insertions and duplications, other EGFR TKIs may be more effective. For example, the second-generation EGFR TKI PF-00299804 compound (Pfizer; discussed further below) has been shown to induce a partial response in a least one patient with an EGFR exon 20 insertion133. For genomic alterations that co-occur with EGFR mutations, drug combinations could be pursued (FIGS 4,6). For example, as IGF1R signalling can mediate disease persistence through the PI3K–AKT pathway87, addition of a GF1R-specific antibody (reviewed in REF. 134) or a PI3K or AKT inhibitor to TKI treatment could be beneficial. Finally, for EGFR-wild-type tumours, multiple approaches are being taken, based on the presence of other driver mutations (in genes such as ALK, KRAS and BRAF) that are found in these tumours. This topic has been reviewed elsewhere (for example, REF. 135).

Acquired resistance

Acquired resistance remains a major clinical problem in EGFR-mutant lung cancer, usually occurring within a year of starting treatment. Based on the molecular mechanisms discussed above and additional studies discussed below, multiple clinical trials have been initiated and/or are being planned.

Second-generation EGFR TKIs

Second-generation EGFR inhibitors were touted to overcome T790M-mediated resistance136,137. These agents were shown, at least in pre-clinical models, to be more potent against the second-site mutation than gefitinib or erlotinib. However, their clinical efficacy remains to be established (TABLE 2).

Irreversible EGFR inhibitors make a covalent bond with C797 of the EGFR (TABLE 2). The first drug tested, HKI-272 (neratinib; Wyeth), showed promising preclinical results138 but no responses were reported in a Phase I trial involving 14 patients with NSCLC with EGFR-positive tumours (measured by IHC) and six patients who had previously progressed on erlotinib achieved stable disease139. The Phase II trial showed an overall RR of 3% but no responses were observed in patients who had tumours that harboured T790M140. Interestingly, three of the four patients with a G719X mutation had a partial response and the remaining patient had stable disease. This drug is no longer being developed for the treatment of lung cancer.

Multiple other second-generation irreversible EGFR inhibitors have also entered the clinic. BIBW2992 (afatinib; Boehringer Ingelheim) has potent activity against EGFR and ERBB2 and can overcome T790M-mediated resistance in vitro and in vivo121,141 (TABLE 2). Multiple Phase II and Phase III trials are currently underway in patients with EGFR-mutant and TKI-naive NSCLC and in patients who have progressed on previous TKI treatment. PF-00299804 also binds irreversibly with activity against all ERBB family members (TABLE 2). It has also shown efficacy against H1975 (EGFR L858R and T790M) cells and xenograft models142,143. Results from early clinical trials are pending.

Continuous exposure of EGFR-mutant NSCLC cell lines to gefitinib or erlotinib has derived clinically relevant mechanisms of acquired resistance (for example, cells with T790M or MET amplification)41,83,144, validating this approach as an in vitro tool to anticipate resistance mechanisms. Using a similar strategy, HKI-272 and BIBW2992 also select for T790M-harbouring clones54,145. In vitro, gefitinib-resistant cells already harbouring T790M further amplify the T790M allele on exposure to PF-0299804 (REF. 146). The limited efficacy of second-generation irreversible EGFR TKIs has been corroborated by chemogenomic profiling of a panel of irreversible compounds113. The growth inhibitory potential of these agents was limited by decreased target binding in the presence of the T790M mutation. Collectively, these data suggest that these three irreversible inhibitors are more potent than erlotinib against T790M but that their clinical efficacy will be limited by pharmacokinetic issues — that is, can the levels of drug achieved in patients be high enough to inhibit T790M without toxicity?

Third-generation EGFR TKIs

Recently, a new compound, WZ4002 (Gatekeeper Pharmaceuticals), was discovered through screening different core chemical scaffolds for their ability to fit in the ATP-binding pocket of EGFR specifically in the presence of T790M147. Instead of the quinazoline core used in all reversible and irreversible inhibitors to date (TABLE 2), WZ4002 is built on an anilinopyrimidine core that fits the gatekeeper mutation while binding irreversibly to C797. In contrast to existing second-generation EGFR TKIs, this agent selectively targets T790M-harbouring receptors (TABLE 2) and induces greater growth inhibitory effects in vitro and in vivo against double-mutant EGFRs than those harbouring only drug-sensitizing mutations or wild-type EGFR. Therefore, the data suggest that T790M-harbouring receptors will be inhibited effectively at doses that will not affect wild-type EGFR and cause toxicity.

Drug combinations

Based on the mechanisms of primary and acquired resistance in EGFR-mutant NSCLC, several rational combinations have been tested in preclinical models (FIGS 4,6). To simultaneously target signalling from EGFR and its downstream target AKT, irreversible EGFR inhibitors have been paired with mTOR inhibitors. Combination therapy with BIBW2992 and rapamycin resulted in greater tumour shrinkage than either agent alone in transgenic mice with T790M-containing lung tumours141,148. Whether this strategy is efficacious in patients with acquired resistance remains to be established. Dual inhibition of EGFR with BIBW2992 and cetuximab also seems a promising strategy, because only this combination of agents effectively targets EGFR T790M54 (FIG. 4). A clinical trial with these agents is currently underway.

As MET signalling can also contribute to TKI resistance, multiple MET inhibitors are being investigated for their potential activity in tumours that harbour these resistance mechanisms (FIG. 4). Antibodies targeting HGF (AMG102), MET (MetMAb) and small molecular inhibitors of MET (reviewed in REF. 149) are currently in development (FIGS 4,6). Notably, many of these trials may demonstrate limited efficacy. For example, trials of a second-generation EGFR TKI will not address tumours with MET amplification, and trials with a MET inhibitor plus gefitinib or erlotinib will not address tumours harbouring T790M. Moreover, heterogeneous mechanisms of resistance can exist in different tumours in the same individual (see below).

Finally, the question of whether to continue treatment with an EGFR TKI in patients who develop acquired resistance and do not participate in clinical trials with EGFR inhibitors has not yet been answered. In standard oncology practice, progression on TKI leads to the permanent discontinuation of that therapy and the initiation of an alternative therapy, usually one involving cytotoxic agents. However, the disease flares and re-responses to drug discussed above suggest that continued EGFR TKI suppression is likely to be beneficial even after disease progression has developed.

Tumour heterogeneity and resistance

The exact percentage of resistant cells necessary to confer what appears clinically as radiographic progression within a tumour lesion is currently unknown. Moreover, whether resistant tumours are a homogeneous mass of TKI-resistant cells or a heterogeneous mixture of sensitive and resistant cells is almost impossible to determine from routine biopsy samples. However, several lines of evidence support the hypothesis that resistant tumours are a mixture of sensitive and resistant cells. First, the pre-existence of rare cells harbouring MET amplification and/or the T790M mutation in untreated tumours suggest that these subpopulations may be selected for over the course of TKI therapy77,102. Second, the re-treatment phenomenon (discussed above) suggests that different populations of tumour cells may become dominant under different conditions118. Collectively, these data suggest that at every stage of treatment, patients’ tumours should ideally be freshly profiled as comprehensively as possible to assign the most appropriate and rationally based therapy.

Preventing or delaying acquired resistance

An alternative long-term strategy to address the problem of acquired resistance to TKIs is to delay or prevent the acquisition of resistance (FIG. 6). One approach is to investigate the effect of different dosing strategies using existing drugs, as the optimal dosing regimens for EGFR-mutant tumours have not been studied. Mathematical modelling suggests that different dosing schedules may influence the time to acquired resistance without compromising efficacy150. A similar observation in CML has been documented in which transient inhibition of breakpoint cluster region (BCR)–ABL with dasatinib (Sprycel; Bristol–Myers Squibb) induced similar killing rates as chronic exposure151. Alternatively, multiple potential combination strategies have been elucidated to treat patients earlier rather than later in the course of their disease (FIG. 4).

Perspective

Over a short period of time, translational research has described a new clinically relevant molecular subset of NSCLC that is defined by EGFR mutations. Today, patients with metastatic disease can achieve survival rates at least double that of patients with wild-type EGFR tumours. Through the rational dissection of the mechanisms of drug sensitivity and resistance, promising strategies have been defined to further improve the outcomes of patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancer. This molecular-centric approach will hopefully serve as a paradigm for how to understand and treat other cancers for which targets and/or targeted therapies have already been or remain to be established.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to apologize to those whose work was not included owing to space constraints. They thank C. Lovly, K. Politi and M. R. Brewer for their insightful feedback on the manuscript, and M. R. Brewer for assistance with the crystal structure diagrams. This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Cancer Institute (NCI) grants R01-CA121210, P01-CA129243 and U54-CA143798. W.P. received additional support from Vanderbilt’s Specialized Program of Research Excellence in Lung Cancer grant (CA90949) and the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center (VICC) core grant (P30-CA68485).

Glossary

- Driver mutation

An oncogenic mutation that induces and sustains tumorigenesis

- Oncogene addiction

The phenomenon in which cancer cells become dependent on or addicted to signalling from oncogenic mutants for survival

- Primary resistance

The initial resistance to therapy

- Gefitinib

The first quinazoline-based reversible small-molecule EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor

- Erlotinib

An FDA-approved quinazoline-based EGFR inhibitor

- Prospective single-arm study

A clinical trial in which a drug is administered in a prospective manner to a single group of patients (defined by certain characteristics) to see whether their condition improves. Single-arm studies are distinct from two-arm studies, in which a group of patients is randomly administered one of two possible treatments (for example, an experimental treatment versus standard treatment) to determine which treatment is better

- Response rate

RR. The proportion of patients undergoing a documented radiographic response as determined by response evaluation criteria in solid tumours

- Progression-free survival

PFS. The length of time during and after treatment in which a disease does not progress

- Time to progression

TTP. Time from the beginning of treatment until treatment failure

- Never smoker

An individual who has smoked <100 cigarettes in their lifetime

- Former light smoker

An individual who has stopped smoking for at least 15 years previously and has a total of ≤10 pack-years of smoking

- Carboplatin–paclitaxel

An example of a platinum doublet for first-line treatment of NSCLC

- Hazard ratio

HR. A measure of how often an event happens in one group compared with how often it happens in another group

- Confidence interval

CI. A calculated value that shows the range in which a particular treatment effect is likely to be observed

- Chimeric IgG monoclonal antibody

A recombinant antibody made from two species (in the case of cetuximab, the fusion contains human and mouse sequences)

- Acquired resistance

Resistance that develops after the initial response to therapy

- Gatekeeper residue

A conserved residue that lies at the opening of the ATP-binding pocket in several kinases

- Disease flare

Rapid tumour growth following withdrawal of therapy

- Resistance mutation screen

A comprehensive cell-based screen to identify all potential mutations in a target gene that confer resistance to a given agent

- Irreversible EGFR inhibitor

A small-molecule inhibitor that binds permanently in the ATP-binding pocket of EGFR through a covalent bond at C797

- Chemogenomic profiling

The technique of coupling chemical compound sensitivity to genomic signatures

- Quinazoline core

A scaffold built on the fusion of a benzene ring and a pyrimidine ring

- Anilinopyrimidine core

A scaffold built on an anilino group and pyrimidine ring

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare competing financial interests; see Web version for details.

References

- 1.Jemal A, et al. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstraw P, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification of malignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:706–714. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31812f3c1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hansen HH, et al. Combination chemotherapy of advanced lung cancer: a randomized trial. Cancer. 1976;38:2201–2207. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197612)38:6<2201::aid-cncr2820380602>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinstein IB. Cancer. Addiction to oncogenes — the Achilles heal of cancer. Science. 2002;297:63–64. doi: 10.1126/science.1073096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hynes NE, Lane HA. ERBB receptors and cancer: the complexity of targeted inhibitors. Nature Rev Cancer. 2005;5:341–354. doi: 10.1038/nrc1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marks JL, et al. Prognostic and therapeutic implications of EGFR and KRAS mutations in resected lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:111–116. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318160c607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herbst RS, et al. Selective oral epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor ZD1839 is generally well-tolerated and has activity in non-small-cell lung cancer and other solid tumors: results of a Phase I trial. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3815–3825. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albanell J, et al. Pharmacodynamic studies of the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor ZD1839 in skin from cancer patients: histopathologic and molecular consequences of receptor inhibition. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:110–124. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ranson M, et al. ZD1839, a selective oral epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is well tolerated and active in patients with solid, malignant tumors: results of a phase I trial. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2240–2250. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.10.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakagawa K, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic trial of the selective oral epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor gefitinib (‘Iressa’, ZD1839) in Japanese patients with solid malignant tumors. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:922–930. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kris MG, et al. Efficacy of gefitinib, an inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, in symptomatic patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2149–2158. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.16.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukuoka M, et al. Multi-institutional randomized Phase II trial of gefitinib for previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (The IDEAL 1 Trial) J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2237–2246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller VA, et al. Bronchioloalveolar pathologic subtype and smoking history predict sensitivity to gefitinib in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1103–1109. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lynch TJ, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paez JG, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pao W, et al. EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from ‘never smokers’ and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13306–13311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405220101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen KS, Kobayashi S, Costa DB. Acquired resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancers dependent on the epidermal growth factor receptor pathway. Clin Lung Cancer. 2009;10:281–289. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2009.n.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shepherd FA, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thatcher N, et al. Gefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer) Lancet. 2005;366:1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67625-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mok TS, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin–paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. This paper presents results from IPASS (a randomized prospective Phase III clinical trial), which demonstrated the superiority of gefitinib over chemotherapy for the treatment of East Asian patients with chemotherapy-naive metastatic pulmonary adenocarcinoma harbouring EGFR mutations. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitsudomi T, et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised Phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;11:121–128. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X. This paper presents results from the WJTOG3405 trial (a randomized prospective Phase III clinical trial), which demonstrated the superiority of gefitinib over chemotherapy in prospectively genotyped Japanese patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller VA, et al. Molecular characteristics of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, bronchioloalveolar carcinoma subtype, predict response to erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1472–1478. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosell R, et al. Screening for epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:958–967. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904554. This paper shows the effectiveness of erlotinib in Caucasian (Spanish) patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maemondo M, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2380–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530. References 20–24 definitively establish the clinical role of EGFR mutations and EGFR TKIs in lung cancer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang CH, et al. Specific EGFR mutations predict treatment outcome of stage IIIB/IV patients with chemotherapy-naive non-small-cell lung cancer receiving first-line gefitinib monotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2745–2753. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han SW, et al. Predictive and prognostic impact of epidermal growth factor receptor mutation in non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with gefitinib. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2493–2501. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pao W, Ladanyi M. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutation testing in lung cancer: searching for the ideal method. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4954–4955. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han SW, et al. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of lung: potential target of EGFR-directed treatment. Lung Cancer. 2008;61:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Neill ID. Gefitinib as targeted therapy for mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the lung: possible significance of CRTC1–MAML2 oncogene. Lung Cancer. 2009;64:129–130. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coxon A, et al. Mect1–Maml2 fusion oncogene linked to the aberrant activation of cyclic AMP/CREB regulated genes. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7137–7144. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Behboudi A, et al. Molecular classification of mucoepidermoid carcinomas-prognostic significance of the MECT1–MAML2 fusion oncogene. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45:470–481. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirsch FR, et al. Increased epidermal growth factor receptor gene copy number detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization associates with increased sensitivity to gefitinib in patients with bronchioloalveolar carcinoma subtypes: a Southwest Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6838–6845. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cappuzzo F, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor gene and protein and gefitinib sensitivity in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:643–655. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirsch FR, et al. Molecular predictors of outcome with gefitinib in a Phase III placebo-controlled study in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5034–5042. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsao MS, et al. Erlotinib in lung cancer — molecular and clinical predictors of outcome. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:133–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirsch FR, et al. Combination of EGFR gene copy number and protein expression predicts outcome for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with gefitinib. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:752–760. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parra HS, et al. Analysis of epidermal growth factor receptor expression as a predictive factor for response to gefitinib (‘Iressa’, ZD1839) in non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:208–212. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yeo WL, et al. Erlotinib at a dose of 25 mg daily for non-small-cell lung cancers with EGFR mutations. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:1048–1053. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181dd1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gandhi J, et al. Alterations in genes of the EGFR signaling pathway and their relationship to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor sensitivity in lung cancer cell lines. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bean J, et al. MET amplification occurs with or without T790M mutations in EGFR mutant lung tumors with acquired resistance to gefitinib or erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20932–20937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710370104. This work confirms MET amplification as a mechanism of acquired resistance to gefitinib, extends the finding to erlotinib and shows that resistance can occur with or without the T790M change. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Engelman JA, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316:1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. This paper reports the discovery of MET amplification as a mechanism of acquired resistance to gefitinib in cell line models and patient samples in mediating resistance. References 40 and 41 establish MET amplification as a mechanism of acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs in lung cancer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosell R, Viteri S, Molina MA, Benlloch S, Taron M. Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors as first-line treatment in advanced nonsmall-cell lung cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2010;22:112–120. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32833500d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mendelsohn J, Baselga J. Epidermal growth factor receptor targeting in cancer. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:369–385. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bonner JA, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:567–578. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jonker DJ, et al. Cetuximab for the treatment of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2040–2048. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hanna N, et al. Phase II trial of cetuximab in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5253–5258. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosell R, et al. Randomized Phase II study of cetuximab plus cisplatin/vinorelbine compared with cisplatin/vinorelbine alone as first-line therapy in EGFR-expressing advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:362–369. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pirker R, Minar W. Chemotherapy of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Front Radiat Ther Oncol. 2010;42:157–163. doi: 10.1159/000262471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lynch TJ, et al. Cetuximab and first-line taxane/carboplatin chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results of the randomized multicenter Phase III trial BMS099. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:911–917. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.9618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mukohara T, et al. Differential effects of gefitinib and cetuximab on non-small-cell lung cancers bearing epidermal growth factor receptor mutations. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1185–1194. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khambata-Ford S, et al. Analysis of potential predictive markers of cetuximab benefit in BMS099, a phase III study of cetuximab and first-line taxane/carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:918–927. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.2890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li S, et al. Structural basis for inhibition of the epidermal growth factor receptor by cetuximab. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:301–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ji H, et al. The impact of human EGFR kinase domain mutations on lung tumorigenesis and in vivo sensitivity to EGFR-targeted therapies. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:485–495. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Regales L, et al. Dual targeting of EGFR can overcome a major drug resistance mutation in mouse models of EGFR mutant lung cancer. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3000–3010. doi: 10.1172/JCI38746. This paper identifies a potential new strategy to overcome T790M-mediated resistance using a small-molecule inhibitor (BIBW2992) combined with an EGFR-specific antibody (cetuximab) in an EGFR-L858R and T790M transgenic mouse model. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Soh J, et al. Oncogene mutations, copy number gains and mutant allele specific imbalance (MASI) frequently occur together in tumor cells. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7464. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Balak MN, et al. Novel D761Y and common secondary T790M mutations in epidermal growth factor receptor-mutant lung adenocarcinomas with acquired resistance to kinase inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6494–6501. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weir BA, et al. Characterizing the cancer genome in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2007;450:893–898. doi: 10.1038/nature06358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ding L, et al. Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2008;455:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature07423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chitale D, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of lung cancer reveals loss of DUSP4 in EGFR-mutant tumors. Oncogene. 2009;28:2773–2783. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yun CH, et al. Structures of lung cancer-derived EGFR mutants and inhibitor complexes: mechanism of activation and insights into differential inhibitor sensitivity. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yun CH, et al. The T790M mutation in EGFR kinase causes drug resistance by increasing the affinity for ATP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2070–2075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709662105. This paper proposes that the T790M mutation in EGFR causes drug resistance by restoring the affinity for ATP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carey KD, et al. Kinetic analysis of epidermal growth factor receptor somatic mutant proteins shows increased sensitivity to the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, erlotinib. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8163–8171. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Red Brewer M, et al. The juxtamembrane region of the EGF receptor functions as an activation domain. Mol Cell. 2009;34:641–651. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Godin-Heymann N, et al. Oncogenic activity of epidermal growth factor receptor kinase mutant alleles is enhanced by the T790M drug resistance mutation. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7319–7326. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mulloy R, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutants from human lung cancers exhibit enhanced catalytic activity and increased sensitivity to gefitinib. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2325–2330. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gong Y, et al. Induction of BIM is essential for apoptosis triggered by EGFR kinase inhibitors in mutant EGFR-dependent lung adenocarcinomas. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Costa DB, et al. Effects of erlotinib in EGFR mutated non-small cell lung cancers with resistance to gefitinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7060–7067. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cragg MS, Kuroda J, Puthalakath H, Huang DC, Strasser A. Gefitinib-induced killing of NSCLC cell lines expressing mutant EGFR requires BIM and can be enhanced by BH3 mimetics. PLoS Med. 2007;4:1681–1690. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Deng J, et al. Proapoptotic BH3-only BCL-2 family prote in BIM connects death signaling from epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition to the mitochondrion. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11867–11875. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1961. References 66–69 show that the pro-apoptotic BCL-2 family member BIM is required for EGFR TKI-induced apoptosis in EGFR-mutant lung cancer and that the BCL-2 antagonist ABT-737 can enhance TKI-induced cell killing. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Faber AC, Wong KK, Engelman JA. Differences underlying EGFR and HER2 oncogene addiction. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:851–852. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.5.11096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shigematsu H, et al. Clinical and biological features associated with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in lung cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:339–346. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Politi K, et al. Lung adenocarcinomas induced in mice by mutant EGF receptors found in human lung cancers respond to a tyrosine kinase inhibitor or to down-regulation of the receptors. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1496–1510. doi: 10.1101/gad.1417406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kosaka T, Yatabe Y, Onozato R, Kuwano H, Mitsudomi T. Prognostic implication of EGFR, KRAS, and TP53 gene mutations in a large cohort of Japanese patients with surgically treated lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:22–29. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181914111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eisenhauer EA, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]