Abstract

A number of human disorders, dubbed ribosomopathies, are linked to impaired ribosome biogenesis or function. These include but are not limited to: Diamond Blackfan anemia (DBA), Shwachman Diamond syndrome (SDS) and the 5q- myelodysplastic syndrome. This review focuses on the latter two non-DBA disorders of ribosome function. Both SDS and 5q- syndrome lead to impaired hematopoiesis and a predisposition to leukemia. SDS, due to bi-allelic mutations of the SBDS gene, is a multi-system disorder that also includes bony abnormalities, pancreatic and neurocognitive dysfunction. SBDS associates with the 60S subunit in human cells and has a role in subunit joining and translational activation in yeast models. In contrast, 5q- syndrome is associated with acquired haploinsufficiency of RPS14, a component of the small 40S subunit. RPS14 is critical for 40S assembly in yeast models, and depletion of RPS14 in human CD34+ cells is sufficient to recapitulate the 5q- erythroid defect. Both SDS and the 5q- syndrome represent important models of ribosome function and may inform future treatment strategies for the ribosomopathies.

Introduction

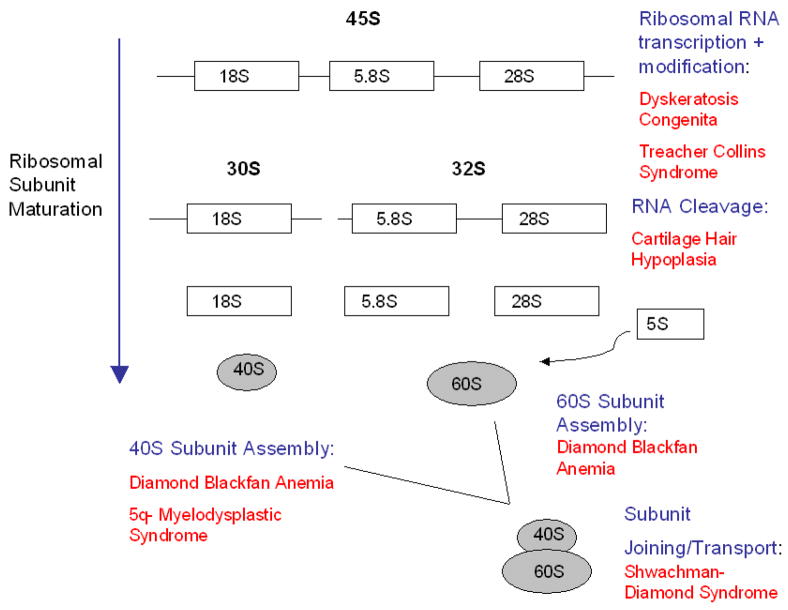

The preceding set of reviews has focused on DBA as a disorder of ribosome biogenesis, with additional emphasis on the possible role of p53 in its pathology. However, DBA may be only one of a number of human disorders of ribosome biogenesis or function, which have collectively been dubbed “ribosomopathies”1 (Fig. 1). As has been commented upon before2, most of these are inherited bone marrow failure syndromes, suggesting a specific link between ribosome biogenesis and hematopoiesis. In this review, we focus on Shwachman Diamond syndrome (SDS) and the 5q- syndrome, comparing and contrasting each with DBA. We conclude by examining the therapeutic implications arising from viewing each disorder through the prism of ribosome biology.

Fig. 1. Gene products from the ribosomopathies and their putative roles in the ribosome biogenesis pathway.

Figure modified from Narla and Ebert, Blood 2010, with permission.

Shwachman Diamond Syndrome

History and Background

In 1964 Shwachman and colleagues first described a pediatric clinical syndrome characterized by “pancreatic insufficiency and bone marrow hypoplasia.” The report of three affected children, all from one family, suggested a genetically inherited disease3. This inherited disease, which was subsequently given the eponym Shwachman-Diamond Syndrome (SDS), was further recognized as a multi-system disorder with additional clinical manifestations including skeletal, cardiac, hepatic and immunologic impairments. Patients often present early in childhood due to malabsorption, recurrent infection, or growth abnormalities. However, a subset of patients may present more insidiously in adulthood. Neutropenia is the most common hematologic abnormality, though anemia and/or thrombocytopenia may also be seen. It has been recognized that SDS patients have an increased risk of severe aplastic anemia or myelodysplasia (MDS) and a predisposition to acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). As a result, SDS is included in the category of inherited bone marrow failure syndromes (IBMF).

In 2003 Boocock and colleagues4,5 first reported mutations in the SBDS gene in the 7q11 centromeric region, in a series of patients with the clinical phenotype of SDS. Since then, approximately 90% of SDS patients have been found to have bi-allelic mutations in the SBDS gene, inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern. These inherited SBDS mutations appear to arise from a gene conversion event between the SBDS gene and an adjacent pseudo-gene. This adjacent pseudo-gene shares 97% sequence identity with the SBDS gene, but contains deletions and nucleotide changes that result in a non-functional SBDS protein. The most common mutation (258+2T->C) is a splice site mutation, while the second most common mutation (183-184TA->CT) is an early truncating mutation with complete loss of SBDS function. The relative estimated allele frequency of SDS is 1/140, with a reported live birth incidence of about 1 in 76,000, which suggests that the disease is under recognized6. Patient registries vary in their reported frequencies of SDS. In the published NIH registry7, SDS represented only 7% of the reported IBMF cases, whereas in the Canadian IBMF study, SDS represented 27% of cases8.

The SBDS protein is part of a highly conserved family of proteins, with homologues in over 150 species from archaea to eukaryotes. SBDS is expressed throughout all embryonic stages and throughout most adult tissues, including liver, lung, pancreas, bone marrow, brain and testis9. Furthermore, some level of functional SBDS protein appears to be essential for human life, as no patients have been found to be homozygous for early truncating SBDS mutations. Additionally, SBDS ablation is embryonic lethal in murine models9. The precise function of SBDS is poorly understood, however recent evidence suggests that SBDS plays an important role in ribosome biogenesis. There is evidence for extra-ribosomal functions of SBDS as well, including promotion of mitotic spindle stability, cellular stress responses, and additional potential functions10–13. However, the role of SBDS in ribosome function will be the focus of this review.

SBDS and Ribosome Function

Comparative genomic analysis of SBDS homologues suggest a common role in RNA metabolism and translation-associated function5. Proteomic analysis of the SBDS homologue YLR022C in Saccharomyes cerevisiae also points to an association of SBDS with ribosome biosynthesis. YLR022C co-purifies with proteins associated with the 60S subunit and those involved with ribosomal RNA synthesis14. In a separate study, the yeast SBDS ortholog Sdo1p was found to interact with the nucleolar protein Nip7p, the RNA helicase Prp43p, and Rpl3p, a component of the large ribosomal subunit. Sdo1p also co-precipitated with the pre-ribosomal RNAs 27S and 23S and the mature ribosomal RNAs 25S, 5.8S and 18S by a non-sequence specific mechanism15,16. Interactions with large ribosomal subunit proteins (L1, L2 and L14) were also seen with the Methanothermobacter SBDS orthologue17. Together, these studies support the association of SBDS with the large ribosomal subunit.

The role of SBDS in ribosome function has been further elucidated in yeast models. Deletion of the yeast SBDS ortholog Sdo1 results in a slow growth phenotype and translational impairment. Translational dysfunction is evidenced by a reduction in the number of polysomes and monosomes, and an under-accumulation of the large 60S subunit in Sdo1 mutants18. Interestingly, this phenotype can be rescued by gain of function TiF6 mutations. Tif6 is a shuttling factor that associates with pre-60S ribosomes and is required for their synthesis and nuclear export19. Therefore, Sdo1 appears to function in the release and recycling of Tif6 from pre-60S ribosomes18. This process is likely critical for translational activation, since 80S assembly occurs only after release of eIF6 from 60S subunits in mammalian cells20.

Since SDS and Diamond Blackfan anemia (DBA) each impact ribosome function, Moore and colleagues compared the yeast Sdo1 mutant to the yeast DBA mutant (Rpl33A) to elucidate distinct mechanisms of ribosome perturbation. Both mutations resulted in defects in 60S subunit maturation. While Rpl33A mutants demonstrated enhanced decay of early ribosomal precursors, Sdo1 mutants showed accumulation of 60S subunit precursors in the nucleoplasm at a later stage of maturation21. These yeast models point to specific biologic effects of SBDS on ribosome function, which are distinct from DBA effects (Fig. 1). Similar comparative studies in human cells will be important to validate the different mechanisms of ribosome dysfunction in DBA versus SDS.

Consistent with its role in ribosome function in yeast models, the SBDS protein is enriched in the nucleolus of human cells10. This nucleolar localization of SBDS is dependent on active ribosomal RNA transcription and can be diminished by treatment with low doses of actinomycin D, an inhibitor of RNA polymerase I. Furthermore, SBDS-deficient cells from SDS patients are hypersensitive to low doses of actinomycin D, an effect that can be restored by the introduction of a wildtype SBDS cDNA. As in yeast, human SBDS protein associates with the large 60S ribosomal subunit22. SBDS interacting proteins have also been evaluated in human cell lines. In an unbiased proteomics assessment of interacting partners of SBDS in human cells, SBDS was found to interact with nucleophosmin, a multifunctional protein implicated in ribosome biogenesis22. In HEK293 cells, several ribosomal proteins were significantly associated with SBDS including RPL3, RPL6, RPL7, RPL7A and RPL8. Nucleolin and nucleophosmin (NPM1), were also shown to be interacting partners with SBDS in this model12.

The association of SBDS with ribosomal proteins was further supported in a study of primary cells from SDS patients. Gene expression profiles of bone marrow mononuclear cells from these patients showed significant down regulation of ribosomal protein genes, including RPS9, RPS20, RPL6, RPL15, RPL23 and RPL29. Alternatively, there was up-regulated expression of RPS27, a gene whose protein product is involved in the p53 response and apoptosis-induction23. Importantly, 58 of the 85 evaluated ribosomal protein genes in this study were not significantly changed, suggesting that SDS deficiency results in a specific impairment of a subset of ribosomal proteins. Ribosomal RNA processing genes and genes involved with rRNA transcription were also affected, including down-regulation of DKC1, which encodes a protein involved in rRNA pseudouridylation as well as telomere maintenance and is mutated in the inherited disorder dyskeratosis congenita24. These studies are congruent with yeast models and further support the hypothesis that loss of SBDS protein perturbs ribosome biosynthesis in human disease.

SBDS and Human Disease

SDS is characterized by a multi-system clinical phenotype. This is not surprising given the wide tissue expression of SBDS and the fundamental role of ribosome biosynthesis in diffuse cellular processes. However, little is known about how SBDS depletion results in tissue-specific dysfunction or why there is such phenotypic heterogeneity between SDS patients. Temporal fluctuations in disease severity may also be seen among individual patients. For example, one-third of SDS patients have sustained neutropenia, while two-thirds of patients have only intermittent episodes25. Anemia and/or thrombocytopenia may also be seen in SDS patients, although at reduced frequencies, and neither is required to make the diagnosis. Both cellular and humoral immunity may be impaired, with noted reductions in natural killer cells, circulating B cells, and low immunoglobulin levels in some patients (reviewed in 26,27). Skeletal abnormalities are also variable. The most common skeletal defect is short stature related to abnormal growth plate development. However, other bony defects may be seen including narrowed rib cage, digit abnormalities (clinodactyly, syndactyly), or spinal deformities such as kyphosis or scoliosis. A particularly striking example of temporal changes in the SDS phenotype relates to the common presentation of exocrine pancreatic dysfunction. As a result of this dysfunction, SDS patients may present in early infancy with malabsorption and failure to thrive. Imaging and pathologic studies in these patients have shown that the pancreatic acinar cells may be extensively replaced with fat. Yet in about half of patients, the exocrine pancreatic function spontaneously improves over time. The reasons for this improvement are unclear. However, the mechanisms involved in this recovery, such as activation of compensatory pathways, could provide important clues to disease biology.

A recent murine model provided unexpected insights into SBDS biology. In this study28, specific deletion of Dicer1 in osteoprogenitor cells, but not in mature osteoblasts, resulted in myelodysplasia and leukemia predisposition. Dicer1 has a broad role as an Rnase III endonuclease required for microRNA biogenesis and RNA processing. Transcriptional profiling of the Dicer1 deleted osteoprogenitor cells revealed differential expression of 656 genes. Of the differentially expressed genes, there was significantly reduced expression of SBDS. In addition, targeted deletion of SBDS in osteoprogenitor cells was able to recapitulate many of the phenotypic features of Dicer1 deletion. Histologic findings included bony abnormalities, increased marrow vascularity, and dysplastic megakaryocytes and neutrophils. Lymphopenia but not neutropenia was seen. Although neutropenia is seen in the majority of SDS patients, these histologic findings are otherwise comparable to clinical phenotypes seen in human SDS. Furthermore, SBDS depletion in HeLa cells has been shown to result in significant up-regulation of VEGF-A and osteoprotegerin. Together these findings suggest an association between SBDS depletion and dysregulated angiogenesis and osteoclast activity29.

In addition to a role for SBDS in normal stromal function, a cell-intrinsic role in hematopoietic cells has been demonstrated in both human and mouse models. Knockdown of Sbds protein in murine hematopoietic cells is sufficient to induce defects in granulocytic differentiation, myeloid progenitor generation and short-term hematopoietic engraftment30. Sbds depletion in this murine model resulted in a significant reduction in peripheral blood lymphocytes but not in circulating granulocyte levels. However, bone marrow myeloid cells depleted of Sbds formed less granulocytic CFU-GM colonies, while there was no difference in erythroid colonies formed, when compared to appropriate controls. The underlying mechanisms responsible for a block in myeloid versus erythroid differentiation are not known. In addition, it is not clear how differences in perturbed ribosome function would lead to different hematopoietic phenotypes in SDS versus DBA. Yeast models show distinct ribosomal maturation defects elicited in SBDS versus DBA mutants21, therefore it is provocative to speculate if (and how) these differences uniquely impact the hematopoetic program. Finally, although neutropenia is typically the most prominent cytopenia in SDS patients, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and lymphopenia are also common, and a subset of patients develop severe aplastic anemia. These findings argue for a global role for SBDS in hematopoiesis.

SDS is also known to be associated with a predisposition to MDS and AML, and patients often acquire increasing clonal cytogenetic abnormalities over time. These clonal abnormalities may persist in a benign state or evolve to a leukemic phase. For example, clones of isochrome i(7)(q) may be present for years without transformation and can fluctuate in levels over this period31. A second commonly seen cytogenetic abnormality in SDS patients is del 20 (q11q13). However, similar to the i7q clone, this abnormality does not appear to be sufficient or required for progression to MDS or AML32. These findings suggest that the SDS genotype facilitates chromosomal instability. However, it is likely that additional non-ribosomal functions of SBDS, such as its role in mitotic spindle stabilization, contribute to this instability. In vitro studies demonstrate that SBDS functions directly on microtubule stabilization, which argues against this being a secondary result of altered protein translation11. Additional cell-intrinsic or -extrinsic modifiers are likely important for the phenotypic heterogeneity in SDS patients.

Treatment options for SDS patients who develop marrow failure, MDS or leukemia are limited, but one available modality is hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HCT). The number of published series for transplantation in SDS patients is small; however HCT is reported to have worse outcomes in those SDS patients with leukemia compared to those with bone marrow failure alone. In a series of 26 SDS patients undergoing HCT from the European Group for Blood and Bone Marrow Transplantation, overall survival was 65% at a median follow-up of 1.1 years25,33. Deaths were primarily related to transplant-related morbidity, including infections, graft-versus host disease or organ toxicity. Poor donor cell engraftment has not been reported at an increased rate in SDS patients34. However, long-term follow up of transplanted SDS patients will be helpful to evaluate the potential role of the bone marrow stroma in MDS-leukemia development. For example, relapses should be evaluated for donor versus recipient-derived cellular origin.

Summary and Future Directions

SDS is an autosomal recessive disorder that is associated with bi-allelic mutations in the SBDS gene, resulting in depletion of SBDS protein and resultant multi-organ dysfunction. There is increasing evidence that SBDS is a multi-functional protein with an important role in ribosome function and that loss of SBDS has profound implications for diverse cellular processes. In particular, SDS is a rare but important cause of inherited bone marrow failure and pediatric MDS/leukemia. However there are still many unanswered questions and few treatment options. Future work should aim to further our understanding of compensatory pathways that may overcome the ribosome production defects in SDS patient cells.

5q- Syndrome

Background and Clinical Features

The 5q–syndrome is a distinct subtype of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) that is recognized as a separate entity by the World Health Organization35. In 1974 Van den Berghe first described the 5q– syndrome, noting the consistent association of the loss of the long arm of chromosome 5 [del(5q)] with macrocytic anemia, erythroblastopenia, normal or high platelet count and hypolobulated megakaryocytes in the bone marrow36. Subsequently, a female preponderance was noted in the syndrome, as well as a more favorable prognosis than other forms of MDS, with low rates of transformation to acute myeloid leukemia (AML). However, a major cause of morbidity and mortality is the erythroid defect, which often requires recurring erythrocyte transfusions resulting in transfusional hemosiderosis. 5q_ syndrome patients also uniquely respond to treatment with the thalidomide analog lenalidomide37, which belongs to a new class of immunomodulatory compounds38.

Molecular Cytogenetics of the CDR

For three decades since its original description, the pathogenesis of the 5q- syndrome has been attributed to hemizygous loss of chromosomal loci resulting in allelic insufficiency of one or more tumor suppressor genes with corresponding mutation of the remaining copy of the same gene. Only recently has it been suggested that haploinsufficiency is responsible for the molecular pathogenesis of the 5q- syndrome (as well as DBA).

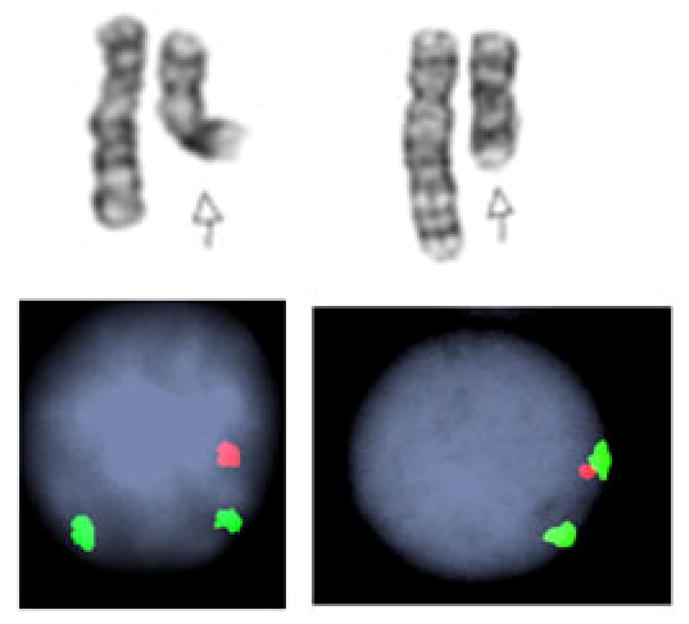

The 5q deletion is a large interstitial deletion (Fig. 2), which can be divided into one of three types (reviewed in35): del(5)(q13q31), del(5)(q13q33) or del(5)(q22q35). 5q deletions present in the 5q- syndrome are cytogenetically identical to those seen in other forms of MDS and AML (5q31 is almost always deleted in MDS). The first important study39 defined the common or critical deleted region (CDR) in 5q- syndrome as a 1.5-Mb interval located on 5q32, between D5S413 and the gene encoding glycine receptor a-1 (GLRA1). Genomic annotation of the CDR was performed and several promising candidate genes were noted, including the secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine gene (SPARC); RPS14, a component of the 40S ribosomal subunit; and several microRNA (miRNA) genes. All the 40 genes within the CDR were sequenced and no mutations were found40, suggesting that haploinsufficient loss of a single gene allele could account for the syndrome (in contrast to other forms of MDS).

Fig. 2. Two different 5q- interstitial deletions.

Interphase FISH shows that in each patient, EGR1 (red) locus from 5q31 chromosomal segment was deleted, while the control probe (green) signal from D5S23 segment hybridizing to 5p15.2 region was present in disomy. Figure courtesy of Prof. Vesna Najfeld, Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY.

Molecular Link Between 5q- Syndrome and DBA

Similar to DBA, the hematopoietic defect in 5q- syndrome includes a failure in the normal synchronized wave of erythroid expansion and terminal differentiation on exposure to erythropoietin. There had also been a report of haploinsufficiency for RPS14 in the CD34+ cells of patients with the 5q- syndrome40, again bringing up a possible analogy with DBA. However, a molecular link was firmly established following a systematic RNAi screen interrogating the functional consequences of suppressing expression of each gene within the CDR: only knockdown of RPS14 in CD34+ cells resulted in a block in erythroid differentiation (and subsequent erythroid cell apoptosis) with relative preservation of megakaryocyte differentiation41. Moreover, enforced expression of an RPS14 cDNA in primary bone marrow cells from patients with the 5q– syndrome rescued the phenotype41.

In yeast, Rps14 directly binds 18S rRNA and is essential for the assembly of 40S ribosomal subunits42,43. Rps14 is apparently needed for the endonucleolytic cleavage that generates mature 18S rRNA and functional 40S ribosomal subunits44. Upon depletion of Rps14, both ribosomal proteins and rRNA destined for 40S subunit assembly are degraded, whereas 60S subunits assemble at normal rates43. By analogy, the specific function of RPS14 in humans likely involves the assembly of 40S ribosomal subunits.

Ubiquitous Role of p53 and the 5q- Mouse Model

Since the CDR is about 1.5 Mb in length, traditional targeting methods cannot be used to create a mouse model. Consequently, Cre-loxP recombination-based chromosome engineering was used to delete major regions of murine chromosomes 11 and 18 in hematopoietic stem cells45. The deletions used were syntenic to human 5q31 and mimicked the loss of DNA sequences between 5q31–5q32, a region containing 40 known or predicted genes, including Sparc and the fat tumor-suppressor protein (Fat2) on murine chromosome 11 and Rps14 on murine chromosome 18. Since mice with a deletion of approximately 1 Mb of chromosome 11 (as well as two additional knockout mouse models of Sparc and Fat2) did not have hematopoietic defects, the investigators focused on a region of murine chromosome 18, between Cd74 and Nid67, which harbors Rps14. Deletion of the Cd74–Nid67 interval in mice resulted in macrocytic anemia with morphologic evidence of dysplasia in the erythroid and megakaryocytic lineages, but not thrombocytosis, which is also a typical feature of 5q- syndrome patients. Since the 5q- mouse has only a single copy of the Rps14 gene, haploinsufficiency of Rps14 was presumed to be responsible for the phenotypic abnormalities.

Bone marrow cells from the Cd74–Nid67-deleted mice also expressed elevated levels of the tumor suppressor p53, although the levels of apoptosis were not significantly different compared with control mice45. Given the elevated levels of p53, the investigators focused their attention on the link between Rps14 haploinsufficiency and ribosomal stress. Intercrossing the 5q- mice with p53-null mice was able to completely rescue the progenitor cell defect (macrocytic anemia and dysplasia), underscoring the key role of p53-dependent mechanisms in the pathogenesis of the 5q- syndrome45.

As discussed elsewhere in this series of reviews, the p53 pathway is activated by DNA damage, oxidative stress, oncogene expression, and defects in ribosomal biogenesis. Stabilization of p53 leads to cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis. In the models of DBA created in mice46 and zebrafish47 by haploinsufficiency of Rps19, the resulting anemia could be abrogated by concurrent genetic inhibition of p53. These experiments point to a close similarity in the pathologic role played by p53 in both DBA and the 5q- syndrome.

MicroRNAs and Thrombocytosis

Some cardinal features of the 5q- syndrome, namely thrombocytosis, megakaryotypic hyperplasia and clonal dominance were not explained by RPS14 haploinsufficiency, thus suggesting that the full phenotype may be a consequence of allelic insufficiency of multiple genes and/or noncoding regions within the CDR.

A second line of investigation has been the identification of noncoding microRNAs (miRNAs) on 5q33.1 that are deleted in patients with the 5q- syndrome48. The miRNAs are key regulators of transcription and translation, and their expression patterns are altered in various cancers and leukemia. Levels of miR-143, miR-145 and miR-146a were significantly reduced in 5q- bone marrow cells. Two genes involved in innate immunity Toll-IL-1 receptor domain-containing adaptor protein (TIRAP) and TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), were identified as key targets of miR-145 and miR-146a, respectively. Both signaling molecules in the Toll receptor pathway, TIRAP and TRAF6 (an E3 ubiquitin ligase) are required for the activation of nuclear factor (NF)-kB. Reduction in the levels of miR-145 and miR- 146a were correlated with increased TRAF6–TIRAP activity and expression. Transplantation of murine cells that overexpress TRAF6 resulted in a phenotype of thrombocytosis, mild neutropenia, dysplastic megakaryopoiesis, and a propensity to AML. In these experiments, TRAF6-mediated interleukin-6 (IL-6) secretion contributed to dysplastic hematopoiesis and thrombocytosis, but the development of AML was independent of IL-6 secretion and attributed to cell-autonomous effects of TRAF6 overexpression. Thus, the full leukemia phenotype seen may be due to both cell non-autonomous (niche) and cell autonomous (genetic) factors.

Current and Future Therapy for 5q- Syndrome Patients

Currently, lenalidomide is the mainstay of therapy for the 5q- syndrome, rendering nearly 70% of patients transfusion-independent and inducing cytogenetic responses in over 40%37. The molecular basis of this remarkable drug response is unknown. Pellagatti et al49 investigated the in vitro effects of lenalidomide on growth, maturation, and global gene expression in isolated erythroblast cultures from MDS patients with del(5)(q31). Lenalidomide was shown to inhibit the growth of differentiating del(5q) erythroblasts but did not affect cytogenetically normal cells. Moreover, lenalidomide significantly influenced the pattern of gene expression in del(5q) intermediate erythroblasts. Recently, allelic haploinsufficiency for the Cdc25C and PP2Acα phosphatases has been implicated in the selective suppression of 5q- clones by lenalidomide50. However, this hypothesis would predict only 5q- MDS patients with allelic loss of these two phosphatase genes to be drug-responsive, and there are insufficient data to confirm this at present.

In addition to its effects on erythropoiesis, lenalidomide also modulates expression of a wide array of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, IL-2 and IFN-γ38. Considering the putative role of IL-6 in the pathogenesis of the 5q- syndrome, it is possible that the responses induced by lenalidomide are due to downregulation of IL-6. This would suggest that inhibitors of the TRAF6–IL-6 axis might be useful in treating manifestations of the 5q- syndrome.

Finally, as in DBA, the putative role of p53 in the pathophysiology of bone marrow failure suggests that inhibitors of p53’s pro-apoptosis/pro-senescence activities may be clinically useful. However, such therapy must not irreversibly abrogate the essential tumor suppressor function of p53.

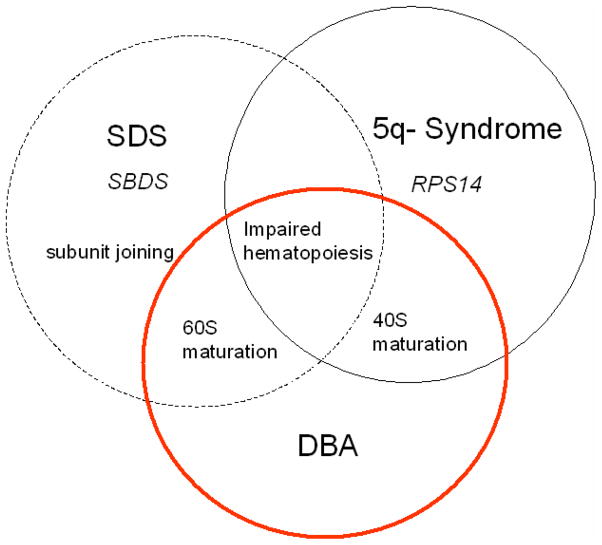

Commentary on Nosology of 5q- Syndrome and DBA

There are clear genetic differences between DBA and the 5q- syndrome, with germline mutations in the ribosomal proteins in the former and somatic deletions that include RPS14 in the latter. In addition, the 5q- syndrome may also involve deletions in miR-143, miR-145 and miR-146a, which appear to modulate the full phenotype of the syndrome. However, the link between the two disorders (Fig. 3) raises a number of intriguing questions. First, what are the phenotypic differences between the acquired 5q- syndrome and genetic DBA? If the pathophysiology of DBA mimics that of 5q- syndrome, can lenalidomide be used to treat DBA? Do some patients labeled with DBA actually have acquired haploinsufficiency for ribosomal proteins? Answering these important questions should clarify the nosology of DBA and the 5q- syndrome and suggest new diagnostic and therapeutic paradigms.

Fig. 3. Venn diagram of disorders affecting ribosome function.

The non-DBA disorders Shwachman Diamond syndrome (SDS) and 5q- syndrome have overlapping features with DBA. Both SDS and DBA can be associated with impairment of 60S maturation. SBDS may also specifically affect 40S/60S subunit joining. SBDS is also recognized as a multi-functional protein with non-ribosome actions. 5q- syndrome and DBA can both have impaired 40S subunit maturation. However, 5q- syndrome is an acquired haploinsufficiency of RPS14, while DBA may be associated with inherited mutations of either 40S or 60S ribosomal proteins. SDS, DBA and 5q- syndrome all share in common impaired hematopoiesis, which is a manifestation of many of the ribosomopathies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Narla A, Ebert BL. Ribosomopathies: human disorders of ribosome dysfunction. Blood. 2010 doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-178129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu JM, Ellis SR. Ribosomes and marrow failure: coincidental association or molecular paradigm? Blood. 2006;107:4583–4588. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shwachman H, Diamond LK, Oski FA, Khaw KT. The syndrome of pancreatic insufficiency and bone marrow dysfunction. J Pediatr. 1964;65:645–663. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(64)80150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boocock GR, Morrison JA, Popovic M, et al. Mutations in SBDS are associated with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;33:97–101. doi: 10.1038/ng1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boocock GR, Marit MR, Rommens JM. Phylogeny, sequence conservation, and functional complementation of the SBDS protein family. Genomics. 2006;87:758–771. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goobie S, Popovic M, Morrison J, et al. Shwachman-Diamond syndrome with exocrine pancreatic dysfunction and bone marrow failure maps to the centromeric region of chromosome 7. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:1048–1054. doi: 10.1086/319505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alter BP, Giri N, Savage SA, et al. Malignancies and survival patterns in the National Cancer Institute inherited bone marrow failure syndromes cohort study. Br J Haematol. 2010;150:179–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08212.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hashmi SK, Allen C, Klaassen R, et al. Comparative analysis of Shwachman-Diamond syndrome to other inherited bone marrow failure syndromes and genotype-phenotype correlation. Clin Genet. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang S, Shi M, Hui CC, Rommens JM. Loss of the mouse ortholog of the shwachman-diamond syndrome gene (Sbds) results in early embryonic lethality. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6656–6663. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00091-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Austin KM, Leary RJ, Shimamura A. The Shwachman-Diamond SBDS protein localizes to the nucleolus. Blood. 2005;106:1253–1258. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Austin KM, Gupta ML, Coats SA, et al. Mitotic spindle destabilization and genomic instability in Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1511–1518. doi: 10.1172/JCI33764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ball HL, Zhang B, Riches JJ, et al. Shwachman-Bodian Diamond syndrome is a multi-functional protein implicated in cellular stress responses. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3684–3695. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orelio C, Verkuijlen P, Geissler J, van den Berg TK, Kuijpers TW. SBDS expression and localization at the mitotic spindle in human myeloid progenitors. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7084. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Savchenko A, Krogan N, Cort JR, et al. The Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome protein family is involved in RNA metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19213–19220. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414421200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luz JS, Georg RC, Gomes CH, Machado-Santelli GM, Oliveira CC. Sdo1p, the yeast orthologue of Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome protein, binds RNA and interacts with nuclear rRNA-processing factors. Yeast. 2009;26:287–298. doi: 10.1002/yea.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hesling C, Oliveira CC, Castilho BA, Zanchin NI. The Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome associated protein interacts with HsNip7 and its down-regulation affects gene expression at the transcriptional and translational levels. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:4180–4195. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng CL, Waterman DG, Koonin EV, et al. Conformational flexibility and molecular interactions of an archaeal homologue of the Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome protein. BMC Struct Biol. 2009;9:32. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-9-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menne TF, Goyenechea B, Sanchez-Puig N, et al. The Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome protein mediates translational activation of ribosomes in yeast. Nat Genet. 2007;39:486–495. doi: 10.1038/ng1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Basu U, Si K, Warner JR, Maitra U. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae TIF6 gene encoding translation initiation factor 6 is required for 60S ribosomal subunit biogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1453–1462. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.5.1453-1462.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ceci M, Gaviraghi C, Gorrini C, et al. Release of eIF6 (p27BBP) from the 60S subunit allows 80S ribosome assembly. Nature. 2003;426:579–584. doi: 10.1038/nature02160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore JB, Farrar JE, Arceci RJ, Liu JM, Ellis SR. Distinct ribosome maturation defects in yeast models of Diamond-Blackfan anemia and Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Haematologica. 2010;95:57–64. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.012450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganapathi KA, Austin KM, Lee CS, et al. The human Shwachman-Diamond syndrome protein, SBDS, associates with ribosomal RNA. Blood. 2007;110:1458–1465. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-075184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rujkijyanont P, Adams SL, Beyene J, Dror Y. Bone marrow cells from patients with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome abnormally express genes involved in ribosome biogenesis and RNA processing. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:806–815. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heiss NS, Knight SW, Vulliamy TJ, et al. X-linked dyskeratosis congenita is caused by mutations in a highly conserved gene with putative nucleolar functions. Nat Genet. 1998;19:32–38. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burroughs L, Woolfrey A, Shimamura A. Shwachman-Diamond syndrome: a review of the clinical presentation, molecular pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:233–248. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dror Y. Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:892–901. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dror Y, Ginzberg H, Dalal I, et al. Immune function in patients with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2001;114:712–717. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raaijmakers MH, Mukherjee S, Guo S, et al. Bone progenitor dysfunction induces myelodysplasia and secondary leukaemia. Nature. 2010;464:852–857. doi: 10.1038/nature08851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nihrane A, Sezgin G, Dsilva S, et al. Depletion of the Shwachman-Diamond syndrome gene product, SBDS, leads to growth inhibition and increased expression of OPG and VEGF-A. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2009;42:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rawls AS, Gregory AD, Woloszynek JR, Liu F, Link DC. Lentiviral-mediated RNAi inhibition of Sbds in murine hematopoietic progenitors impairs their hematopoietic potential. Blood. 2007;110:2414–2422. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-007112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cunningham J, Sales M, Pearce A, et al. Does isochromosome 7q mandate bone marrow transplant in children with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome? Br J Haematol. 2002;119:1062–1069. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maserati E, Pressato B, Valli R, et al. The route to development of myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukaemia in Shwachman-Diamond syndrome: the role of ageing, karyotype instability, and acquired chromosome anomalies. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:190–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cesaro S, Oneto R, Messina C, et al. Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for Shwachman-Diamond disease: a study from the European Group for blood and marrow transplantation. Br J Haematol. 2005;131:231–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakamoto KM, Shimamura A, Davies SM. Congenital disorders of ribosome biogenesis and bone marrow failure. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:S12–S17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boultwood J, Pellagatti A, McKenzie AN, Wainscoat JS. Advances in the 5q- syndrome. Blood. 2010 doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-273771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van den BH. The 5q- syndrome. Scand J Haematol Suppl. 1986;45:78–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.List A, Kurtin S, Roe DJ, et al. Efficacy of lenalidomide in myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:549–557. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bartlett JB, Dredge K, Dalgleish AG. The evolution of thalidomide and its IMiD derivatives as anticancer agents. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:314–322. doi: 10.1038/nrc1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boultwood J, Fidler C, Strickson AJ, et al. Narrowing and genomic annotation of the commonly deleted region of the 5q- syndrome. Blood. 2002;99:4638–4641. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boultwood J, Pellagatti A, Cattan H, et al. Gene expression profiling of CD34+ cells in patients with the 5q- syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2007;139:578–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ebert BL, Pretz J, Bosco J, et al. Identification of RPS14 as a 5q- syndrome gene by RNA interference screen. Nature. 2008;451:335–339. doi: 10.1038/nature06494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Larkin JC, Thompson JR, Woolford JL., Jr Structure and expression of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae CRY1 gene: a highly conserved ribosomal protein gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:1764–1775. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.5.1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moritz M, Paulovich AG, Tsay YF, Woolford JL., Jr Depletion of yeast ribosomal proteins L16 or rp59 disrupts ribosome assembly. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:2261–2274. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jakovljevic J, de Mayolo PA, Miles TD, et al. The carboxy-terminal extension of yeast ribosomal protein S14 is necessary for maturation of 43S preribosomes. Mol Cell. 2004;14:331–342. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barlow JL, Drynan LF, Hewett DR, et al. A p53-dependent mechanism underlies macrocytic anemia in a mouse model of human 5q- syndrome. Nat Med. 2010;16:59–66. doi: 10.1038/nm.2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGowan KA, Li JZ, Park CY, et al. Ribosomal mutations cause p53-mediated dark skin and pleiotropic effects. Nat Genet. 2008;40:963–970. doi: 10.1038/ng.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Danilova N, Sakamoto KM, Lin S. Ribosomal protein S19 deficiency in zebrafish leads to developmental abnormalities and defective erythropoiesis through activation of p53 protein family. Blood. 2008;112:5228–5237. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-132290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Starczynowski DT, Kuchenbauer F, Argiropoulos B, et al. Identification of miR-145 and miR-146a as mediators of the 5q- syndrome phenotype. Nat Med. 2010;16:49–58. doi: 10.1038/nm.2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pellagatti A, Jadersten M, Forsblom AM, et al. Lenalidomide inhibits the malignant clone and up-regulates the SPARC gene mapping to the commonly deleted region in 5q- syndrome patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11406–11411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610477104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wei S, Chen X, Rocha K, et al. A critical role for phosphatase haplodeficiency in the selective suppression of deletion 5q MDS by lenalidomide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:12974–12979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811267106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]